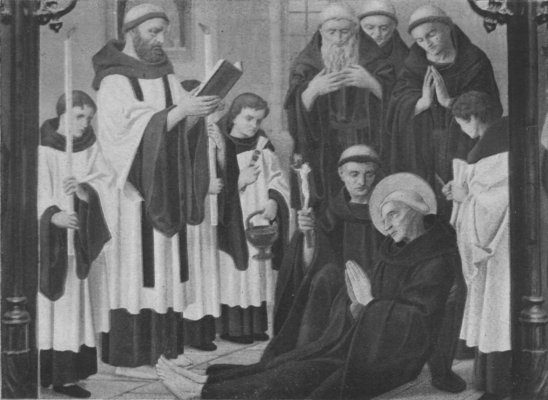

Death of St Bede. (From the Original Picture at St Cuthbert's College, Ushaw.)

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Our Catholic Heritage in English Literature of Pre-Conquest Days, by Emily Hickey This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Our Catholic Heritage in English Literature of Pre-Conquest Days Author: Emily Hickey Release Date: October 1, 2005 [EBook #16785] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK OUR CATHOLIC HERITAGE IN *** Produced by Kathryn Lybarger and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

The beginnings of Literature in England. Two poets of the best period of our old poetry, Caedmon and Cynewulf. The language they wrote in. The monastery at Whitby. The story of Caedmon's gift of song. page 15

Caedmon and his influence. Poem, "Genesis." "The Fall of the Angels." "Exodus." English a war-loving race. Destruction of the Egyptians. Fate and the Lord of Fate. 24

Allegory. Principle of comparison important in life, language, literature. Early use of symbolism; suggested reasons for this. Poem of the Phœnix. Allegorical interpretation of the story. Celtic influence on English poetry. Gifts of colour, fervour, glow. Various gifts of various nations enriching one another. 31

Prose-writing. St Bede the Venerable. His love of truth. His industry and carefulness. Cuthbert's account of his last days. "Bede whom God loved". 42

King Alfred, first layman to be a great power in literature; man of action; of thought; of endurance. Freedom first great possession; afterwards learning and culture. Alfred a loyal Son of the Church. Founder of English prose. Earliest literature of a nation in verse; why. Influence of Rome on Alfred. 48

Decay of learning in England. Revival under Alfred. His translations. Edits English Chronicle. His helpers. Some of his sayings. Missionary spirit. "Alfred commanded to make me". 55

Some of greatest pre-Conquest poetry associated with name of Cynewulf. Guesses about him. Little known. Probably North-countryman, eighth century, an educated man. Finding of the Cross. Elene, story of St Helena's mission. Constantine goes to fight invaders. Vision of the Cross. Victory. Journey of St Helena, and search for the Cross. The Finding.64

The Poet's love of the Cross: how he saw it in a double aspect. The dream of the Holy Rood. The Ruthwell Cross. 73

"Judith," a great poem founded on Scripture story. Authorship uncertain. Part of it lost. Quotations from it. Description of Holofernes' banquet as a Saxon feast. Story of Judith dwelt on to encourage resistance to Danes and Northmen. 83

Byrthnoth, the leader of the East Angles against Anlaf the Dane. Refusal to pay unjust tribute. Heroic fight. 90

The literature of one people owes a debt to that of others. Help-bringers. Great work of Benedictine monks. Our debt to Ireland. The English Chronicle's account of the Martyrdom of St Ælfeah. 97

Abbot Ælfric, writer of Homilies, Lives of Saints, and other works. Wulfstan, Archbishop of Canterbury. 104

Love of books is love of part of God's world. In books we commune with the spirit of their writers. The Church the mother of all Christian art and literature. Catholic literature saturated with Holy Scripture. 110

Scattering of our old MSS. in Sixteenth Century. Some now in Public Libraries. Collections, Exeter book and Vercelli Book. 114

Runes. An early love poem. 118

| Death Of Saint Bede | Frontispiece | |

| Whitby Abbey | Page | 19 |

| King Alfred the Great | " | 48 |

| The Ruthwell Cross | " | 80 |

| The Alfred Jewel | " | 114 |

| A Saxon Ship | " | 114 |

This little book makes no claim to be a history of pre-Conquest Literature. It is an attempt to increase the interest which Catholics may well feel in this part of the great 'inheritance of their fathers.' It is not meant to be a formal course of reading, but a sort of talk, as it were, about beautiful things said and sung in old days: things which to have learned to love is to have incurred a great and living debt. I have tried to clothe some of these in the nearest approach I could find to the native garb in which their makers had sent them forth, with the humblest acknowledgement that nothing comes up to that native garb itself. In writing the book I have naturally incurred debt in various directions; debt of which the source would be difficult always to trace. I may mention my obligations to the work of Professor Morley, Professor Earle, Professor Ten Brink, and Professor Albert S. Cook: also to the writers of Chapters I-VII of "The Cambridge History of English Literature," vol. i.

If this little book in any way fulfils the wishes of those Catholic teachers who have asked me to print some thoughts of mine about English Literature, I shall be glad indeed.

How many of us I wonder, realise in anything like its full extent the beauty and the glory of our Catholic heritage. Do we think how the Great Mother, the keeper of truth, the guardian of beauty, the muse of learning, the fosterer of progress, has given us gifts in munificent generosity, gifts that sprang from her holy bosom, to enlighten, to cheer, to guide and to help; gifts that she, large, liberal, glorious, could not but give, for she, like her Lord, is giver and bestower; and to be of her children is to be of the givers and bestowers. The Catholic Church is the source of fine literature, of true art, as of noble speech and noble deed.

We are going to look at a small portion of that part of our Catholic heritage which consists of our early literature; we are going to think about the beginning of Christian work of this kind in the form of poetry and prose in England. When I say Christian poetry and prose, I am using the word Christian as opposed to pagan, and inclusive of secular as well as religious verse, though the amount of secular verse is, in the earliest time, comparatively very small. Some of the pagan work was retouched by Christians who cared for the truth and strength and beauty of it. The ideal of the English heathen poet was, in many respects, a fine one. He loved valour and generosity and loyalty, and all these things are found, for instance, in the poem "Béowulf," a poem full of interest of various kinds; full, too, as Professor Harrison says, "of evidences of having been fumigated here and there by a Christian incense-bearer." But "the poem is a heathen poem, just 'fumigated' here and there by its editor." There is a vast difference between "fumigating" a heathen work and adapting it to blessedly changed belief, seeing in old story the potential vessel of Christian thought and Christian teaching. To fumigate with incense is one thing—to use that incense in the work of dedication and consecration is another. For instance, the old story of the "Quest of the Graal," best known to modern readers through Tennyson's "Idylls of the King," has been Christianised and consecrated. And so it was with some fine old English (or Anglo-Saxon) poetry. But, just now, we are going to listen to Catholic poets and teachers only.

We begin with the work of poets. Out of all those who wrote in what was the best period of our old poetry, a period that lasted some hundred and fifty or seventy-five years, we know the names of two only, Caedmon and Cynewulf.

And here may I say that scholars agree that the names are to be pronounced Kadmon and Kun-e-wolf; in the second name we sound the y like a French u, make a syllable of the e, not sounding it as ee, but short, and make the last syllable just what we now pronounce as wolf.

Both of these poets deserve our love and our praise, as singers and inspirers of other singers, but we know much more about Caedmon's life than we know about his share in the poetry that has been attributed to him; that is the poetry which has gone under his name. That he did write much fine verse we know. On the other hand, we know a good deal as to the authenticity of Cynewulf's poetry, and nothing about his life.

Both of these poets wrote in the language spoken in England before the period of French influence. That influence upon English at first seemed to be disastrous; the language became broken up and spoilt: but this was only for a time; and by and by, out of roughness and chaotic grammar there grew up a beautiful and stately speech meet for great poets to sing in, and great men and women to use. So it is that what for a time seems to be disastrous may one day be realised as benign and beautiful.

This pre-Conquest language has to be learned as we learn a foreign tongue. It is much easier to learn than Latin or German, but still it has to be learned; so we shall have to listen to the thought of these poets in the language of our own day, allowing ourselves now and then the use of words or expressions which it is fair to employ in rendering old poetry or prose, though we do not use them in ordinary speech or writing.

We shall sometimes use translations, and sometimes I will tell you about the poetry, giving the gist of it as best I can.

At Whitby you may see the ruins of what must have been a very beautiful monastery, built high on a hill, swept by brisk and health-giving winds with the strength and freshness of moorland and sea. This monastery, part of which was for monks, and part for nuns, was ruled by Abbess Hild.[A] This seems strange to us, but it was because the Celtic usage prevailed in the government of the Abbey.

We must never forget the work of the Celtic missionaries who brought Christianity from the Western Islands to the North of England: and, of course, their "ways" as well as their message were impressed on the converts. Later on, as we know, the Roman usage was established all over the country.

Among the monks of Streoneshalh, as Whitby was then called, the Danes having given it its present name, there was, as St Bede the Venerable tells us, "a brother specially renowned and honoured by Divine grace, because it was his wont to make fitting songs appertaining to piety and virtue; so that whatever he learned from scholars about the Divine Writings, that did he, in a short time, with the greatest sweetness and fervour, adorn with the language of poetry, and bring forth in the English speech. And because of his poems the hearts of many men were brought to despise the world, and were inspired with desire for the fellowship of the heavenly life.... He was a layman until he was far advanced in years, and he had never learnt any songs. It was then the custom that, when there was a feast on some occasion of rejoicing, all present should sing to the harp in turn. And when Caedmon saw the harp coming near him, he would get up, feeling ashamed, and go home to his house. Now once upon a time he had done this and had left the house where they were feasting, and gone to the stall where the cattle were, which it was his duty that night to attend to. There, when his work was done, he lay down and slept, and in a dream he saw a man standing by him, who hailed him and greeted him and called him by his name, saying: 'Caedmon, sing me something.' And Caedmon answered and said, 'I can sing nothing, and therefore did I go from this feast, and depart hither, because I could not.' And again he that was speaking with him, said: 'Nevertheless, thou must sing for me.'"

Then Caedmon understood, and he said in the same spirit that prompted Our Lady's "Be it done unto me according to thy word," "What shall I sing?" And the guest of his dream said, "Sing the Creation for me."

As soon as Caedmon had received this answer, he at once began to sing to the praise of God the Creator verses and words which he had never heard. St Bede quotes a few lines in the Northern dialect, which may be rendered thus:

"Now shall we praise the Guardian of the Kingdom of Heaven, the might of the Creator and the thought of His mind, the works of the Father of glory; how He made the beginning of all wonders, the everlasting Lord. First did He shape for the children of men Heaven for a roof, the holy Shaper. Then the mid-world the Guardian of Mankind, the Eternal Lord, the King Almighty, created thereafter, the earth for men."

When Caedmon awoke the gift remained with him, and he went on composing more poetry. He told the town-reeve about the gift he had received, and the town-reeve took him to the Abbess and showed her all the matter. Abbess Hild called together all the most learned men and the students, and by her desire the dream was told to them, and the songs sung to them that they might all judge what this might be and whence the gift had come. And they were all sure that a divine gift had been bestowed on Caedmon by God Himself. They gave him a holy story and words of divine lore, and bad him sing them if he could, putting them into the measure of verse. In the morning he came back, having set them in most beautiful poetry. And after that the Abbess had him instructed, and he left the life in the world for the religious life. We are told by St Bede that he made much beautiful verse, being taught much holy lore and making songs so winsome to hear that his teachers themselves learned at his mouth.

"He sang of the creation of earth and the making of man, and the history of Genesis, and the going out of the Israelites from the land of the Egyptians, and their entering into the Land of Promise, and many other stories told in the Books of the Canon. He also sang concerning the Humanity of Christ and about His Passion and His Ascension, and about the coming of the Holy Ghost, and the teaching of the Apostles. And he sang also of the Judgement to come and of the sweetness of the Kingdom of Heaven. About these things he made many songs, as well as about the Divine goodness and judgment. And this poet always had before him the desire to draw men away from the love of sin and of evil doing, and to make them earnestly desire to do good deeds."

At last a fair end was set upon his life when, glad of heart, full of love to those around him, he received Holy Viaticum, and prayed and signed himself with the Holy Sign, and entered sweetly into his rest.

This is the story told for the most part, as it is best to tell it in the way in which St Bede recorded it; and Alfred rendered it into the English of his day, from which English I have now taken it.

We possess poems on the subjects which St Bede tells us that Caedmon wrote upon, but we cannot be sure that any of these are actually that poet's work. St Bede tells us that many others after him wrote noble songs, but he sets Caedmon's work above that of all those others as having been the product of a gift direct from God. In any case he must have influenced those who wrote later than he. All our work whether we are poets, thinkers, fighters, craftsmen, servants, tradesfolk, teachers, must be only partly in what we do directly. This can to some extent be measured. We can tell how many hours' work we have done in a day; how many books we have written in a life's working-time; how much faithful service we have consciously offered. But by far the larger part of our work we cannot know. We cannot know how much we may have influenced others for good, we cannot calculate the effect that we have had upon them, and, through them, upon others. And to apply this thought specially to a poet, we may say that what he has done for others by suggesting, by stimulating, by inspiring, is not only a most valuable part of his work, but also an immeasurable part. A poet may inspire another poet simply to sing; or he may inspire him to sing on subjects akin to those dearest to himself; and the second poet, or the third or fourth, as it may be, may sing better than the first. But all the same, he owes it to the first poet, and, in a sense, the work of the latter poet is a part of the work of the earlier.

The poem "Genesis" is known to be the work of at least two people: part of it is a version of an old Saxon paraphrase of the Old Testament, and must have been written later than Caedmon's time. It is always interesting to know who it was that wrote work we care for, but it is a more important matter to possess the work itself. People in old times did not seem to care much whether their names were known or not. The author, for example, of the book which for so long has been read and studied and cherished as one of the Church's most treasured possessions, the "Imitation of Christ," remained for a long time unknown; and this is by no means a solitary instance. The interest in literary fame is mostly a modern thing. Besides in these old times people worked in a different sort of way from now. We must remember that the art of song went hand in hand with the art of verse-making. All sorts of people sang the words they had heard, changing, adding, as it might be; adding to, or taking from the beauty and force of what they were dealing with, in proportion to the strength of their memory, or the quality of their imagination.

The story of the "Fall of the Angels" forms part of the "Genesis," and it is well worth while to consider whether a very great poet of much later days, John Milton, may not have owed something when writing "Paradise Lost" to his early forerunner.

"Ten angel-tribes had the Guardian of all, the Holy Lord, created by the might of His hand, whom He well trusted to work His will in full allegiance to Him, for He had given them understanding and made them with His hands, the Lord Most Holy.

"He had set them in such blessedness. One thereof had He made so strong, so mighty in his intellect; to him did He grant great sway, next to Himself in the Kingdom of Heaven. So bright had He made him, so beautiful was his form in Heaven that was given him by the Lord of Hosts. He was like unto the stars of light. His duty was to praise the Lord, to laud Him because of his share of the gift of light. Dear was he to our Lord."

But it could not be hidden from God how pride had taken hold of His angel. And Satan resolves in that pride not to serve God. Bright and beautiful in his form, he will not obey the Almighty. He thinks within himself that he has more might and strength than the Holy God could find among his fellows. "Why should I toil, seeing there is no need that I should have a lord? With my hands I can work marvels as many as He. Great power have I to make ready a goodlier throne, a higher one in Heaven. Why must I serve Him in liegedom, bow to Him in service? I am able to be God even as He. Strong comrades stand by me, who will not fail me in the strife; stout-hearted heroes."

And so does Satan resolve to be the foe of God.

Surely we must be reminded of Milton's great poem when we read how Satan, ruined and cast into hell, speaks to his comrades, lost with him. He compares the "narrow place" with the seat he had once known in Heaven, and denies the right doing of the Almighty in casting him down. He says too that the chief of his sorrows is that Adam, made out of earth, shall possess the strong throne that once was his; Adam, made after God's likeness, from whom Heaven will be peopled with pure souls. And he plans revenge on God by striving to destroy Adam and his offspring.

All this, and the appeal to one of his followers to go upward where Adam and Eve are, and bring about that they should forsake God's teaching and break His Commandments, so that weal might depart from them and punishment await them, may be compared with "Paradise Lost," Books I, II.

It is needless to say that the English were a war-like race. They loved the clash of swords, the whizzing of the arrow in its flight, the fierce combat, the struggle to keep the battle-stead, as they phrased the gaining of a victory. We shall see more of this by and by. And this spirit comes out in their poetry written after they had received Christianity. They delight in the story of struggle, of brave combat, of victory. They saw in the hosts of Pharaoh the old Teuton warriors, with the bright-shining bucklers, and the voice of the trumpets and the waving of banners. Over the doomed host the poet of "Exodus" saw the vultures soaring in circles, hungry for the fight, when the doomed warriors should be their prey, and heard the wolves howling their direful evensong, deeming their food nigh them. Here is the description of the Destruction of the Egyptians. The translation is by Henry S. Canby:—

How fine a conception it is. Let us notice how far had been travelled from the old pagan "Fate goeth even as it will" to "the Lord of Fate." How great is the thought of the vision of God's might, the power of the Master of the waves, brought before the eyes of Pharaoh before he sinks in the death-grip that will not let him go!

In these papers we are not going through anything like a course of older English literature. We are looking at some of the work which our early writers have left, from the point of view of its being our Catholic Heritage, and we want to pay special attention to special works, not to go through a long list of names. It is hoped that the bringing forward of what is so good and strong in interest may be found really helpful by those who have little or no time to go to the originals. That it may be so is alike the desire of writer and publisher.

To-day we are going to consider a poem of a different kind from what we have had before, an old poem called "The Phœnix."

Literature is full of allusions to the fable of the phœnix; it is one of those stories which have caught hold of people and fired their imagination; and the reason is, we may well suppose, because it has suggested so many comparisons, some of them great and beautiful and holy. There are some stories which lend themselves easily to an allegorical interpretation; stories quite true, and yet suggesting things beyond their own actual scope. I dwell on this before passing on to the poem, because I want to bring before you the remembrance of what a tremendous factor in literature, as in thought and in the whole of life is the principle of comparison, or, as we might put it, the principle of similitude or likeness. We learn about a thing we do not know through its likeness, as a whole or in some parts, to a thing we do know. Our little children can understand most easily something of the love of Our Father who is in Heaven through the love of their father on earth: they learn of their Redeemer's Mother, their own dear Mother of Grace, through their earthly mother, who is ever ready to supply their wants and give them joy and comfort.

In devotion what do we most need to pray for? Is it not for likeness to the holy ones and to the holiest of all creatures, Our Lady; and highest of all, to the Lord, Our Saviour and Example? And is it not the fairest of promises that one day "we shall be like to Him, for we shall see Him as He is"? (St John iii.)

So in literature we have, springing from this principle of comparison, the forms fable, parable, and allegory; and in language the figures of speech which we know as simile and metaphor.

Ovid, a Roman poet who lived before the Incarnation, tells the old Eastern fable thus:

"There is a bird that restores and reproduces itself; the Assyrians call it the Phœnix. It feeds on no common food, but on the choicest of gums and spices; and after a life of secular length (i.e., a hundred years) it builds in a high tree with cassia, spikenard, cinnamon, and myrrh, and on this nest it expires in sweetest odours. A young Phœnix rises and grows, and when strong enough it takes up the nest with its deposit and bears it to the City of the Sun, and lays it down there in front of the sacred portals."

It was a much later and a much longer version of the story that our English poet was debtor to. It was written in Latin by Lactantius, and the fable there, Professor Earle says, "is so curiously and, as it were, significantly elaborated, that we hardly know whether we are reading a Christian allegory or no."

He goes on to say that Allegory has always been a favourite form with Christian writers, and finds more than one reason for it. There was a tendency towards symbolism in literature outside Christianity when the Christian literature arose. Another reason was that the early Christians used it to convey what it would probably have endangered their lives to set in plain words; besides this—here I must give the Professor's own beautiful words—"Christian thought had in its own nature something which invited allegory, partly by its own hidden sympathies with nature, and partly by its very immensity, for which all direct speech was felt to be inadequate." One more reason he suggests, and that is "the all-pervading and unspeakable sweetness of Christ's teaching by parables."

The Romans used the representation of the phœnix on coins to signify the desire for fresh life and vigour, and Christian writers used the phœnix as an emblem of the Resurrection.

Many scholars think that it was Cynewulf who wrote the Anglo-Saxon poem of "The Phœnix." We are, however, uncertain as to its authorship and as to its date. Whoever wrote it probably took some hints as to the allegorical interpretation of the story from both St Ambrose and St Bede. And this poet, too, gives us much more brightness and colour than we find in Caedmonic poetry. I use the word "Caedmonic" to cover the poetry which used to be attributed to Caedmon, and which was probably written under his influence. That he did write much I have shown in Chapter I.

I cannot give the poem at full length, but in parts quote from it, and in part give the gist of it. It begins with a description of the Happy Land which is the home of the Phœnix. Far away in the East it lies, that noblest of lands, renowned among men. Not to many of the earth-owners is it given to have access to that country. God's power sets it far from the workers of evil. Beautiful is that plain, with joys endowed and with the sweetest smells of earth. Peerless is the island, set there by its noble Maker. Oft is the door of Heaven opened for the blessed ones and the joy of its music known of them. Winsome is the plain with its wide green woods. And there is neither rain nor snow, nor breath of frost nor flame of fire, nor the rush of hail, nor the falling of rime, nor burning heat of the sun, nor everlasting cold, but blessed and wholesome standeth the plain, and full is the noble country of the blowing of blossoms.

The glorious land is higher than earth's highest towering mountain, lying serene in its sunny wooded fairness. Ever and always the trees are hung with fruits, and never comes the withering of the leaf. No foes may enter that land, and there is no weeping nor any sorrow, nor losing of life, nor sin, nor strife, nor age, nor care, nor poverty. When the Flood covered the earth, this Paradise was shielded from the rush of angry waters, happy through God's grace and inviolate; and so shall it remain even to the day of the coming of the Judgement of the Lord.

In this fair country there abides a bird of wondrous beauty and strong of wing. For him there shall be no death while the world shall last. Ever he watches the course of the sun, eagerly looks for the radiant rising over ocean of the noblest of stars, the first work of the Father, the glowing token of God. At the coming of the sun he flies swift-winged toward it, singing more wondrously than any son of man hath heard since the making of heaven and earth. Never was human voice nor sound of any instrument of music like unto the song. And so twelve times by day he marks the hours, as twelve times by night he has marked them by his bath in the glorious fountain, and his drink of its cool clear water.

A thousand years go on, and the burden of years is upon him, and he flies to a spacious lonely realm and there abides alone. He is lord over all the birds, and dwells with them in the wilderness. He flies westward, attended by a great throng, till he gains the country of the Syrians. Then he sends away his retinue, and stays alone in a grove, hidden from human eyes. Here is a lofty tree, blossoming bright above all other trees, and on this tree the Phœnix builds his nest, on a windless day, when the holy jewel of heaven shines clear. For he is fain by the activity of his mind to convert old age into life, and thus renew his youth. He gathers from far and near the sweetest and most delightsome plants and leaves, and the sweetest perfumes that the Father of all beginnings has made. On the lofty top of the tree he builds his house fair and winsome, and sets round his body holy spices and noble boughs. Then, in the great sheen of mid-day, the Phœnix sits, looking out on the world and enduring his fate. Suddenly his house is set on fire by the radiant sun, and amid the glowing spices and sweet odours, bird and nest burn together in the fierce heat. The life of him, the soul, escapes when the flame of the funeral pile sears flesh and bone.

Then comes the resurrection of the Phœnix, who rises from the ashes of his old body, young and wondrously beautiful. Fed on the honey-dew that oft descends at midnight, he remains a while before his return to his own dwelling-place, his home of yore.

When he goes he is accompanied by a great retinue of the bird-folk, who proclaim him their leader. Ere he reaches his own country he outstrips them all, and comes home alone in his splendour and his might. And the next thousand years go on, and again comes the change to this creature who has no dread of death, since he is ever assured of new life after the fury of the flame.

And so it is that every blessed soul will choose for himself to enter into everlasting life through the dark portals of death. Much of a like kind does this bird's nature shadow forth concerning the chosen followers of Christ, how they may possess pure happiness here, and secure exalted bliss hereafter.

The allegorical significance is explained by the old poet at considerable length. The main thought is, of course, the great Resurrection in which, day by day, we all profess our belief; the Resurrection through the fire that "shall be astir, and shall consume iniquities"; the Resurrection at the Day of Judgement, when the just shall be once more young and comely in the glory of joy and praise, singing in adoration of the peerless King: "Peace and wisdom and blessing for these Thy gifts, and for every good, be unto Thee, the true God, throned in majesty. Infinite, high, and holy is the power of Thy might. The heavens on high with the angels, are full of the glory, O Father Almighty, Lord of all gods, and the earth also. Defend us, Author of Creation. Thou art the Father Almighty in the highest, the Lord of Heaven."

How familiarly these words ring! For our heritage of praise has come to us from afar and from of old.

And again rises the chant triumphant, to the endless honour of the Eternal Son, whose coming into the world and birth and death are all typified by the mystical Phœnix.

I have dwelt at considerable length upon this poem for various reasons. One is that it is of a special kind, the allegorical; another is that, as I have pointed out, it is full of a richness and colour and love of nature, which is not found in the earlier poetry. Where does it come from? It is most probably part of the Celtic influence which has set its magic touch upon English poetry and given to it that "light that never was on sea or land." It has done far more than give a sense of colour and beauty and nature-love. More than the love of nature in its beauty is the sense of fellowship between man and nature, the sense that makes man see his own joy and sorrow reflected in the mighty heart of Nature. This is a very big subject, and can only be touched on here. The beginning of this influence, which came also from Wales and France, is due to Ireland. We must never forget how great a debt England owes to Ireland. May we say that it was from the Irish missionaries whose feet hallowed the soil of Iona that the English north country caught that intense glowing love of the Holy Faith, which even still, in a measure, differentiates the north of England from the south?[C] We must value very greatly the solid foundation of strength, sincerity, what we call grit, directness of expression, simplicity, to be found in early English work; all these being great things, yet capable of receiving into their fellowship and above it and beyond it, that which should give what we look for in a great literature; the power of appeal to various kinds of people, to "all sorts and conditions of men." And to Celtic influence, Irish, British, French, we look for that which turns grey, however fair a grey, to green, and purest pallor to the glory of whiteness. It is beautiful, is it not, to think how various kinds of men and women can help to complete one another by giving and taking what each has to give, and each needs to take? It is the same with nations: each has its own gifts, its own needs; and for a great and noble world-literature we need the gifts of all.

We leave our poets now for a time, and go to the writers of prose in early days. We want first to think about a beautiful-souled religious, who gave us the first great historical work done in England. We know him as St Bede, the Venerable Bede, as he has been called from the epithet inscribed on his tomb in Durham Cathedral, which bears the words

"In this grave are the bones of Venerable Bede." We know the old story how the pupil who was writing his dear master's epitaph could not find the right word, as it has happened to many a one for the time being; and how he slept and awoke to find the word supplied by the gracious angel hand.

In his Benedictine cell at Jarrow, St Bede read and thought and wrote; and all that he wrote was done in noble sincerity of purpose, springing from the dedication of his whole soul to Him who is truth itself. He told as history what he believed to be true, and collected his materials from sources acknowledged to be trustworthy; and he is always careful to tell us when he gives a story on evidence only hearsay.

St Bede refused to be Abbot of Jarrow, because "the office demands household care, and household care brings with it distraction of mind, which hinders the pursuit of learning."

He wrote many things, and it has been said that his writings form nearly a complete encyclopædia of the knowledge of his day; but the work of St Bede by which he is best known is the "Church History of the English Race." It is of greater value than we can tell, and has been used for many generations for knowledge and help.

The history of England was in St Bede's time inseparable from the history of her Church, as we pray that one day it may again come to be.

The book begins with a short account of Britain before the coming of St Augustine. St Bede used old writers for this, and he was much helped by two of his friends, Albinus and Northelm. Northelm used to make researches for him at Rome, and brought him copies of letters written by St Gregory the Great, and other Popes, bearing on the Church history of Britain. From other sources also he took the information which has come down through him to us, a heritage for which we cannot be too grateful. Our two great early histories are the "Anglo-Saxon Chronicle," and Bede's "Church History of the English Race." Without these, what could our historians have done?

This great book of St Bede's was, like almost all his work, written in Latin; the grand old tongue in which our priests say their daily Office and minister at God's altar. It was King Alfred who gave us a free translation of it in English. But although it was written in Latin, it belongs absolutely to our Catholic Heritage in English Literature.

Bede was the first historian to date from the Incarnation of Our Lord, the form which we have always used. The History comes down to a.d. 731, a short time before its author went to his rest. We can never think of St Bede as a mere bookman, a purely "literary man." His own character, truth-loving, wise, devoted, cheerful, has been felt through his work; a character that has made people love him and stretch out hands of affection to him across the heaping-up of the years. How glad are we to say, we, students, workers, all of us, "St Bede, pray for us."

There is a lovely account of St Bede's last days handed down to us in a letter written by his pupil Cuthbert, to another of his pupils, Cuthwin. Cuthwin had written, telling Cuthbert how he was diligently saying Masses, and praying for their "father and master, Bede, whom God loved," and Cuthbert is glad to answer his fellow-student's enquiries as to the departure of that "dear father and master."

His death-illness began "a fortnight before the day of Our Lord's Resurrection," and lasted till Holy Thursday. All the time he was full of joy and thanksgiving. Cuthbert says he has never seen any man "so earnest in giving thanks to the living God."

He made a little poem in English about the absolute importance of everybody considering, before his departure, what good or ill he has done, and how his soul is to be judged after death. "He also sang antiphons," says Cuthbert, "according to our custom and use." Cuthbert gives one of them, which is the lovely antiphon to the "Magnificat" at second Vespers on Ascension Day.

His work went on during his illness. He was making a translation of part of St John's Gospel into English, "for the benefit of the Church," and was working at "Some collections out of the 'Book of Notes' of Bishop Isodorus, saying, 'I will not have my pupils read a falsehood, nor labour therein without profit after my death.'" As the time went on his difficulty of breathing increased, and last symptoms began to appear; but he dictated cheerfully, anxious to do all that he could. On the Wednesday he ordered them to write with all speed what he had begun; and then "we walked till the third hour with the relics of saints, according to the custom of that day."

Then one of them said, "Most dear Master, there is still one chapter wanting: do you think it troublesome to be asked any more questions?" He answered, "It is no trouble. Take your pen, and make ready, and write fast."

After this he distributed little gifts to the priests, and spoke to all, asking that Masses and prayers might be said for him. His desire was, like St Paul's, to die and be with Christ: Christ Whom he had so loved, and at Whose feet he had laid all his gifts and all his learning.

"One sentence more," said the boy, was yet to be written. The Master bad him write quickly. "The sentence is now written," said the boy. And the dear Saint knew that the end was come, and asked them to receive his head into their hands. And there sitting, facing the holy place where he had been used to pray, he sang his last song of praise, "Glory be to the Father and to the Son and to the Holy Ghost," and "when he named the Holy Ghost he breathed his last and so departed to the Heavenly Kingdom."

St Bede was buried at Jarrow, but his relics were afterwards taken to Durham by a priest named Elfrid, and laid by St Cuthbert's side. In the twelfth century a glorious shrine was built over these relics by the Bishop of Durham, Hugh Pudsey: a shrine that, like many another, was destroyed in the sixteenth century uprising of the king of the country against the Church of Our Lord Jesus Christ.

"Let us praise the men of renown," says Holy Scripture (Ecclesiasticus, 44), "and our fathers in their generations.... Such as have borne rule in their dominions, men of great power and endued with their wisdom ... ruling over the present people, and by the strength of wisdom instructing the people in most holy words."

We have to think now of a man of renown who bore rule in his dominions; a man of great power, and endued with wisdom; who by strength and wisdom instructed his people in most holy words. We have hitherto spoken of work done in the dedicated life of religion: to-day we direct our attention to the work of a great layman; the first English layman whom we know to have been a great power in literature; less as a "maker," poet or proseman, than as an opener out to "makers" of precious store; a helper and encourager; a fellow-student; a learner and a teacher of whom it could be said, as Chaucer says of his Clerk of Oxford, "gladly would he learn and gladly teach."

It would not, I think, be possible for English people to over-estimate the value of the gift God gave them in King Aelfred. That is really the right way to spell his name, but as to most people it looks unfamiliar, we will adopt the more usual spelling and write of him as Alfred.

We think of him in various aspects: first as the strong, brave man who did so much toward making noble history for time to come, by his own action, guided by his piety and devotion. His earliest work was to fight for the gaining of freedom and unity for his people, and this work went over many years. When there was an interval of peace, and when a more settled peace had been won, he worked hard to gain for them the freedom of the mind which can never exist where ignorance is reigning. Freedom is the first great possession; afterwards we seek for learning and culture. People who may be called away at any moment to fight for life or liberty cannot do much in the way of quiet study; and while the Danes were not yet finally repulsed or bound by treaty, the great work of Alfred in civilizing England had to remain in suspense.

We love to think that Alfred's wars were not to greaten himself, but to set his country free. Then, as later on, if I may quote what I have elsewhere said, the English

There is another aspect in which we may look at this great King; we think of him not only as a doer but as a sufferer; and not only as an endurer of disappointment, a bearer of toil, difficulty, trouble, but as one who bore in his body a "white martyrdom" of great pain, perhaps even anguish; and this for some twenty years.

Alfred was always a loyal son of the Church. His father, Æthelwulf, sent him to Rome when he was quite a little boy, and Pope Leo IV was godfather to him at his Confirmation, and, on hearing the report of Æthelwulf's death, consecrated him as king, as he had been asked to do. But Æthelwulf did not die for a little time after, and took Alfred for a second visit to Rome. Each of Alfred's three brothers reigned a short time before he became King of Wessex in 871. In that same year he fought no fewer than nine battles against the Danes, besides making sundry raids upon them. It is well to be a good fighting man where need is, and it is well to use the qualities that go to the making up of the good fighting man to meet the difficulties that beset the path of duty and the way of progress. Courage, strength, generosity, perseverance, these are needed for all work alike in peace and war.

Alfred was familiar in his youth with English songs, and most probably knew the old Norse sagas; but he had to learn Latin in his later life. We must remember that most of the literature which Alfred could get at was locked up in Latin; even the invaluable Church History of St Bede needed a translator's key; and it was Alfred who first applied this key to it.

When we think of the prose written in England in early days, we are thinking of the work of scholars, in a grand language that had done growing; a language that was to be in Western Christendom the language of religion, the language of the altar, for how long a time who can know? the language that gave birth to other languages, as its literature so powerfully influenced both theirs and that of others not descended from it. Not yet was the time for a great prose literature in England, such as grew up many a year ago, and is going on in our own days.

The earliest literature of a people is almost invariably in verse: the literature that comes from the heart of a people, and is not the production of a few learned folk. In early days, there was little reading or writing, except in the shelter of the great monasteries. The common folk-literature, which is a very precious thing, is preserved, in such times as we are thinking of, in people's memories, and circulated by recitation, this recitation being accompanied by music or by rhythmical movements of the body. We all know how much easier it is to remember a page of verse than a page of prose. Thus, the form that could most easily be carried in the memory and recited, would naturally be the first to flourish.

We have seen something of early English religious poetry in Caedmon's work and that of his followers; and next we shall come back to poetry with Cynewulf, who made great and holy verse.

But beside such work as these poems which were written by cultivated men, many poems and fragments of verse were floating about the land, come over from the old native country with the first Angles and Saxons who made their home in Britain. These were dear to the people and dear, as we shall see, to the greatest among their kings, Alfred, who was, we may say, the founder of English prose. It was not English prose as we know English prose, because the language was then more like German than anything else; but it was prose in the native tongue, and this was a good and great thing to begin.

In our gratitude to Alfred, we must not forget our gratitude to the English scholars of older days, none of whom had put us under so great a debt as our dear old Benedictine of Jarrow.

A later writer than St Bede, though not so great as he, was Alcuin of York, who was invited by no less a man than Charlemagne to teach his children, and who became, as it has been phrased, a sort of Minister of Public Education in his empire.

Alcuin was good as well as great, and I will give you a little instance of the rightness of his thought. In a Dialogue which he wrote, in his teaching days, he supposes Prince Pepin to ask the question, "What is the liberty of man?" and the answer is, "Innocence."

But the evil days of invasion and war and trouble had swept learning from its northern home; and Alfred's work was to bring it back to another part of England.

We cannot forget the impression that must have been made upon Alfred by his stay in Rome, young as he was at the time, he being in the centre of royal state while there, and also being himself a royal child to whom much would be told and under whose notice much would be brought; and who, from his position, would be expected to mark and remember much. Long afterwards, he would recall the magnificence he had seen, and associate it with the glories of the double history of Rome; Rome pagan and Rome Christian: Rome, the great conqueror and law-giver, spiritual as well as temporal. Very often, after Alfred was king, he sent over embassies and gifts to Rome, loving her, and reverencing her as it was meet he should. The Holy Father granted him certain privileges for the English school at Rome, and sent him a piece of the wood of the Holy Cross.

There is a pretty story told of Alfred's early learning to read English verse. Even if it is not true, it points to his love of English, as well as learning; a love which never left him. He wanted English to be taught in schools, and he loved the old poems. We owe to him the translation of the account of the first English poet, Caedmon, from which I have quoted in my first chapter. But rightly, he felt the very great importance of learning Latin, and so he learned it himself, and made others learn it too.

When Alfred came to the throne, he tells us, learning had fallen away so utterly in England that there were very few of the clergy, on the south side of the Humber, who could understand the Latin of their Mass-books, and he thinks not many beyond the Humber. This state of things was very different from that of old times when the clergy were "so keen about both teaching and learning and all the services they owed to God": very different from St Bede's time, and the days when Northumbria was a centre of learning and culture. Alfred was to create a new centre, not in the North but in Wessex. Later on, the centre of learning and cultivation was shifted to the East Midlands, whose dialect became the language of England, and whose great poet, Chaucer, was the greatest English poet before Spenser and Shakespere.

In his studies Alfred was helped by various friends, the chief of whom was a Welsh Bishop, named Asser. So greatly did Alfred value Asser that he wanted him to live altogether at Court; but Asser felt, it is to be supposed, that this would not be right, and arranged to spend half his time in Wales and half with the King. From him we learn a great deal about Alfred.

One of the Latin books translated by Alfred—perhaps the first—was called the "Pastoral Care" ("Cura Pastoralis"). It was written by St Gregory the Great, and was intended for the clergy as a guide to their duties. The king had a copy sent to every bishopric. He called it the Herdsman's Book, or Shepherd's Book. Sending all these copies made of course a great deal of work for scribes or "bookers," as we may render the old "bóceras," the copyists who had to write out all their books by hand.

As various books had been turned into the "own tongue" of various nations, so would Alfred give to his people in their "own tongue" books of help, of knowledge, of wisdom. This is how Alfred tells us he worked.

"I began to turn into English the book which in Latin is named 'Pastoralis,' and in English 'Shepherd's Book'; sometimes word for word, sometimes meaning for meaning, as I had learned it from Plegmund, my Archbishop, and Asser my Bishop, and from Grimbold, my Mass-priest, and from John, my Mass-priest."

At the end of the translation, Alfred put some little verses of his own.

Alfred as we have seen, translated St Bede's History, omitting many chapters which contained things he may be supposed to have thought were not of general interest. He also edited the English, usually called the Anglo-Saxon, Chronicle, which begins with the invasion of Julius Caesar, and ends with the accession of Henry II. There are a good many MSS. of it, the earliest of which ends with the year 855. We owe this work, as we owe so much beside, to the care of the monks who wrote it, adding to it probably, year by year, sometimes giving poetry as well as prose. It contains several poems, among them the vigorous lay of the Battle of Brunanburh, fought in 937 by Athelstane against the Scots and Danes. You will find a rendering of it among Tennyson's poems, made by him from a prose translation of his son's. This editing of the A.S. Chronicle was very important work, work that has helped generations of history-writers and students. Where should we be without these Histories? How much of it Alfred actually did himself we do not know: we may suppose he had a good deal to do with the chronicling of the events of his own reign. I wonder whether it was he that wrote how three bold Irishmen came over from Ireland in a boat without any rudder, having stolen away from their country, "because they desired for the love of God to be in a state of pilgrimage, they recked not where." They had a boat made of "two hides and a half," and provisions for a week. They got to Cornwall on the seventh day, and soon after went to Alfred. We have no account of their visit to the King, but I think he would have welcomed them right warmly, and loved to hear how big souls ride in little cockleshells. We know their names at least: Dubslane, Macbeth, and Maclinnuim. And immediately after this record we are told something that must also in a different way have greatly interested Alfred. "And Swifneh, the best teacher among the Scots (Irish) died."

Another book that Alfred translated was the History written by a Spanish priest called Orosius, a disciple of St Augustine's (of Hippo), which "was looked upon as a standard book of universal history." Alfred by no means gave a literal translation, but used great freedom, and omitted some things and put in others which he judged of greater interest and importance for Englishmen. Alfred enlarged the account of Northern Europe, which he knew a great deal of. He also added the accounts of the voyages of Ohthere and Wulfstan, the former of whom got round the north of Scandinavia and explored the White Sea. Wulfstan's voyage also was of importance. Both these men told Alfred their stories, and he incorporated them in the History. They came to see him, and Ohthere gave him teeth of the walrus, and no doubt Alfred listened to all they told him, with the keenest interest.

"The account of Ohthere's voyage holds a unique position as the first attempt to give expression to the spirit of discovery."

Alfred knew how to use helpers. All who understand the "ought to be" take help as well as give it. The good King encouraged others, and the office of encourager is no mean part of the office of helper. We cannot do our work in the world alone: God meant us to work with others, and man's best work as an individual can never be independent of the work of others, those who are living or those who have gone before.

Another of the books translated by Alfred was the "Consolations of Philosophy," by a good and thoughtful Consul of Rome, who was put to death by Theodoric, the Arian King of the East Goths. He wrote the book in prison, and there was so much in it that was felt to be in accord with Christian teaching that some people thought Boethius must have belonged to the body of Holy Church.

A Christian writer, finding a book seeming to possess much of the spirit of Christianity, would naturally study it and frequently use it; and Boethius's book, with more or less adaptation, grew to be a great favourite with Christians. Its influence can be traced in the work of the greatest Catholic poet, Dante, and in that of the great English poet, Chaucer, who rendered it into the English of his day.

Alfred made the translation definitely Christian. For instance, he writes of "God" and "Christ" where Boethius says "love" or "the good"; and he writes of "angels" instead of "divine substance."

I will give you one or two specimens of the additions to Boethius with which Alfred is credited.

"He that will have eternal riches, let him build the house of his mind on the footstone of lowliness; not on the highest hill where the raging wind of trouble blows, or the rain of measureless anxiety."

"Power is never a good unless he be good who has it."

Here is what he has to say of being well-born:

"Art thou more fair for other men's fairness? A man will not be the better because he had a well-born father, if he himself is nought. The only thing which is good in noble descent is this, that it makes men ashamed of being worse than their elders, and strive to do better than they."

And here is his standard of self-respect:

"We under-worth ourselves when we love that which is lower than ourselves."[D]

These sayings are worth copying into a little book such as Alfred kept to note down things he wanted to keep track of. Asser tells us this, and he tells us of the "Handbook" which grew to a great size, from this collecting habit of Alfred's. The book was unfortunately lost.

By no means have we exhausted the interest of Alfred's story. It would be indeed difficult to do so; but we must now bid him good-bye.

We love to think how, amidst all his cares and work for his kingdom, he had the true Catholic Missionary spirit; for he sent embassies to India, with alms for "the Christians of St Thomas and St Bartholomew."

There is a valuable thing which we possess, known as the "Alfred Jewel": it has on it an inscription which we can truly say applies to far more than this work of art. Its application to Alfred's work is indeed a very wide one:

We are going now to consider some of the greatest poetry written before the Conquest. It associates itself with the name of Cynewulf, a name with which certain poems are signed in runes. By-and-by we shall hear something about runes and the old writing; and something also about where our old treasures of literature, part of our dear Catholic heritage, are found in their original form.

As I have said, certain poems are signed with Cynewulf's name; and there are others which are with more or less probability of rightness attributed to him on grounds of likeness of subject, likeness of style, similar greatness of treatment.

About Cynewulf himself we know, I may say, nothing except what we gather from his work. Various guesses have been made, and various theories formed, identifying him with one or other of the men about whom we know something; but for the present, at all events, we must be content to think that he probably lived in the eighth century, and that he probably was a North-countryman. All his writings have come to us in the dialect of Wessex, except some parts of a poem known as the "Dream of the Holy Rood." These are carved on an old cross, which I will speak of by-and-by, and they are in the Northumbrian dialect; but the manuscript of the entire poem is in West Saxon.

Scholars are working upon old materials and discoveries are being made and theories formed which are at variance with what used to be set down as certainty. The main thing is that we have these poems, and that we want to know about them and learn to prize them. If we want to know them thoroughly and prize them as they deserve, we must take the trouble to learn the language they are written in. But many of us have not time for this, and so must be content, for the present, at least, with making their acquaintance through translations.

Perhaps Cynewulf was a poet who lived as one of the household of some great lord, and wrote more at his ease than if he had been merely an itinerant singer, a "gleeman," who sang his songs as he went about. He appears, at any rate, to have been an educated man, and I think no one can read his poetry without feeling that he was a man of deep and fervent piety.

There are four poems signed by Cynewulf, and these are named "Christ," "Juliana," "The Fates of the Apostles," and "Elene." Certain "Riddles" have also been attributed to him.

The poems I am going to bring before you now are the "Elene" and a poem on the Holy Cross, which has been attributed to Cynewulf, and which I for one—and I am not by any means alone in this—love to believe that he must have written. The "Phœnix," about which we thought in a former chapter, has by some been supposed to be his. Then there is the "Judith," of which we possess enough to make us recognise it as indeed one of our great possessions; but to-day the two poems I have named will give us enough to think of. To adapt a lovely Scriptural phrase (Judith vii, 7), there are springs whereof we refresh ourselves a little rather than drink our fill. Let us drink, if not our fill, at least a draught long and deep.

We have a church festival, instituted many hundred years ago, the Festival of the Finding of the Cross. Let us hear something of what our old poet sings concerning this in the poem named after the heroine of the finding, St Helena; the poem known as "Elene."

Cynewulf is one of the poets of the Cross. His poetry is literally stamped with the mark of the Holy Rood. Read over the grand Church hymns, the "Vexilla Regis," the "Pange lingua gloriosi lauream certaminis," or recall them in your memory—their Passiontide echoes sound under the triumphant pealing of the bells of Easter—and then be glad that one of your own poets has also sent down the ages the song of his love and his reverence.

Cynewulf knew well the story of Constantine's vision of the Cross of Victory whereby he was to conquer. He would also have had in mind the story, not so far remote from his own day, of the English King, St Oswald, who reared a cross to God's honour before he fought with Cadwalla, the pagan Welsh king. He would remember how the Saint had called upon his comrades at Heavenfield to fall down with him before the Cross and pray Almighty God for salvation from the mighty foe. He would recall the great victory and the cross-shaped church built to commemorate it. He knew well the honour of the Cross. He had often knelt to adore what it symbolised, when he saw it raised on high, lifted up on the Church's Festival. And he loved the Cross with a great and fervid love.

The poem of his making tells us how the great army of the Huns and Goths[E] came against Constantine; how the warriors marched on, having raised the standard of war with shoutings and the clashing of shields. Bright shone their darts and their coats of linked mail. The wolf in the wood howled out the song of war; he kept not the secret of the slaughter. The dewy-feathered eagle raised a song on the track of the foe.

The King of the Romans was sorrow-smitten when he saw the countless host of the foreign men upon the river-bank. In his sleep that night came the vision of one in the likeness of a man, white and bright of hue. The messenger named him by his name. The helmet of night glided apart. The behest was given to look up to Heaven to find help, a token of victory. The Emperor's heart was opened and he looked up as the angel, the lovely weaver of peace, had bidden him. Above the roof of clouds he saw the Tree of Glory with its words of promise. The great battle came, when the Holy Sign was borne forth. Loud sang the trumpets. The raven was glad thereof, and the dewy-feathered eagle looked on at the march, and the wolf lifted up his howling. The terror of war was there, the clash of shields and the mingling of men, and the heavy sword-swing and the felling of warriors.

When the standard was raised, the Holy Tree, the foe was scattered far and wide. From break of day till eventide the flying foe was pursued; his number was indeed made small. It was but a few of the best of the Huns that went home again.

How the old fighting spirit delights in the "pomp and circumstance of glorious war"! How it loves to have the clash of spear and shield strike upon the ear, and to hear how the voice of the eagle and the raven, and the howl of the wolf, proclaim the place of slaughter, the reek of battle!

Cynewulf calls the angel who stood by Constantine in his vision a "weaver of peace"; but the peace was to be woven after conflict, and the wearer of the victor's palm had first to wield the fighter's sword.

When Constantine had learned about the Cross from the few Christians he could find, he believed and was baptized, says the poet. (In reality his baptism took place just before his death, several years later.)

The thought of the Tree was ever with Constantine, and when he had returned he sent his mother with a multitude of warriors to Jerusalem, on the quest of the Holy Rood that was hidden underground. Helena was soon ready for her willing journey, and set forth with her escort.

What delight there is to the poet in the sea and its ships!

When they come to Jerusalem, after much enquiry of the wisest men, and great difficulty, the Queen is conducted to the Mount of Crucifixion, by one Judas who knows the story of Redemption, and who the Queen insists shall point out the resting place of the Holy Rood. It is found by the winsome smoke that rises at the prayer of Judas, who forthwith makes full confession of his belief in Him who hung upon that Cross. The three crosses are together, buried far down in the earth, and Judas digs deep and brings them up, and they are laid before the knees of the Queen. Glad of heart she asks on which of them the Son of the Ruling One had suffered. The Lord's Cross is revealed by its power to raise a dead man who is brought to the place.

Satan assaults Judas, angry and bitter, for again his power has been brought low. One Judas has made him joyful: the second Judas has humbled him. He is boldly answered when he pours out threats and foretells that another king than Constantine will arise to persecute. (Probably the allusion is to Julian the Apostate.) But Judas answers boldly, and Helena rejoices at the wisdom with which in so short a time he has been gifted.

Far and near the glorious news is spread, and word is sent the Emperor how the Victorious Token has been found. Then comes the building of a church by his mother, at his desire; and the adorning of the Rood with gold and jewels fair and splendid, and its enclosure in a silver chest. Judas is baptized, and becomes Bishop of Jerusalem under the new name of Cyriacus.

The holy nails of the Passion have yet to be found, and again the earth yields up her treasure. A man great in wisdom tells Elene to bid the noblest of the kings of the earth to put them on his bridle, make thereof his horse's bit. This shall bring him good speed in war, and blessing and honour and greatness.

Now let us read what our poet says about the Festival of the Finding of the Cross.[F]

The poet wrote about the Holy Cross, not just because it was a picturesque subject, capable of picturesque treatment, one that would make a fine poem; but because, as he tells us, Holy Wisdom had revealed to him "wider knowledge through her glorious power over the thoughts of the mind." He tells us how the fetters of sin had bound him in their bitter bondage, and how, stained and sorrowful, light came to him, and the Mighty King bestowed on him His bountiful grace, and gave him light and liberty, opening his heart and setting free for him the gift of song, that gift which, he says, he has used in the world joyfully and with a good will.

Not once alone, he says, did he meditate upon the Tree of Glory, but over and over again. He thought upon it until all his soul was saturated with it, and hallowed and consecrated for ever.

He may have venerated the Cross in public on the anniversary of the Lord's Crucifixion. Certainly, many a time he had venerated it in private. Perhaps, like Alcuin, his habit was to bow toward the Cross whenever he saw it, and whisper the prayer "Tuam crucem adoramus, Domine, et Tuam gloriosam recolimus passionem."[G]

He was old, he tells us, when he "wove word-craft, made his poem, framing it wondrously, pondering and sifting his thoughts in the night-time."

The Cross had brought him light and healing, and at the foot of the Cross he laid his gift of song.

It is a moot point whether the "Elene" or the "Dream of the Holy Rood" came first. The poetry of the "Dream" is as fine as the conception is grand, and, at whatever time it was written, it must be classed as being at the high-water mark of the poet's work.

Wonderful things have been given to us "under the similitude of a dream"; things beautiful and terrible, things wise and strange. There have been Dreamers of Dreams into whose souls have sunk the sight and the hearing of deep things, high things and precious, of comfort and of warning, of sweetest help and of gravest and most earnest exhortation.

The speech of these Dreamers has sounded in our ears, and has left the vibrations to go on and on for our lifetime: this we call remembering.

In English literature we have some great tellings "under the similitude of a dream." We have the nineteenth-century "Dream of Gerontius," our great Cardinal's drama of the soul in its parting and after. We have the seventeenth-century dream from the darkness of Bedford Gaol, whence John Bunyan saw the pilgrims on their way, through dangers and trials, on to the river that must be crossed before they could come to the Celestial City. We have the fourteenth-century dream of the gaunt, sad-souled William Langley, the dreamer of the Malvern Hills. And, earlier by many a century, we have the dream of the dreamer at the depth of midnight, the midnight whose heart was bright with the splendour of the glorious vesting and gem-adorning of the Cross of Jesus Christ, and dark with the moisture of the Sacred Blood that oozed therefrom.

We have first the simple, quiet prelude.

Then comes the description of the Cross in its glory. It is uplift and girt with light, flooded with gold and set with precious gems. This is followed by the seeing through the glory, the seeing of the anguish. The hues are shifted from dark to bright; the light of gold lights it, and yet anon it is wet, defiled with Blood. Here are the two sides of the Passion: the veiled glory, and the illumined anguish: the supreme might, and the absolute weakness: the darkness of the grave, and the light of the Resurrection.

While time shall be, the Cross is to us all the Book where we may read all we choose to read, all God sends us grace to read. Cynewulf chose to read, and with Cynewulf was the grace of God.

The poet lies beholding the wondrous sight: the sight that all God's fair angels beheld, and all the universe, and men of mortal breath.

The Rood speaks to Cynewulf. To us, with every look upon the Cross, should come, would come, were we alive all through with keen, sweet, spiritual life, the voice telling of the Passion, of the victory, of the glory. Cynewulf heard the Rood tell how long ago it was hewn down, ordained to lift up the evil-doers, to bear the law-breakers.

We notice the obedience of the Cross. In its absolute sympathy with its Creator's agony, its indignation at the horrible crime of His enemies, it would fain have fallen and crushed the gazing foes abhorred. But this was not to be, any more than fire was to come down from heaven at the Boanerges' call when they were fain to avenge the insult put upon their Master, whom the people of the Samaritan city would not receive (Luke ix, 52, etc.).

The Great King is lifted up, and the Rood dare not even stoop: the dark nails pierce the Cross, and it stands, companion of its Maker's agony and shame.

How great is the poet's insight! How deeply must he have entered into the fellowship of that supreme suffering! He knows that throughout creation that cup is being drunk from, as even yet it is in the groaning and travailing of every creature, waiting for the adoption of the sons of God, to wit, the redemption of the body (Romans viii, 22, 3).

The Descent from the Cross and the Burial come next. Tenderly, after the telling of the anguish, comes the telling of the rest.

The bitter weeping goes up. The fair Body waxes chill. Then, in a very few words the story told in "Elene" is condensed.

The glory comes after the shame, and we hear of the healing power of the Cross, and the honour given to it. Even as Almighty God honoured His Mother above all womankind, the poet says, so this tree is set high above all trees of the forest.

The command is laid upon the poet to make known his vision. There is a compulsion whereby a poet as it were has to send abroad the fair thought and knowledge wherewith he has been graced. To this poet is the task assigned to tell of the Crucifixion, of the Resurrection, and the Ascension, and of the Second Coming to judge the world.

By the love of His name, by the love that means martyrdom in will if not in deed also, shall men be judged.

The comfort of his life has come to the poet. The greatest of all great things is his.

I cannot close this chapter without saying something about the great stone rood known as the Ruthwell Cross, because it bears upon it part of this poem engraved in runes. The cross is at Ruthwell, in Dumfriesshire. It is very old, probably dating from the tenth or eleventh century. There are carvings upon it of various events in the life of Our Lord, on the north and south sides. On the top-stone, north, is a representation of St John with the eagle, and on the top-stone, south, is St John with the Agnus Dei. On the east and west is carved a vine in fruit, with animals feeding, and at each side of the vine-tracery the runes are carved, which give the words taken from the poem, in the Northumbrian dialect.

This cross used to stand in the church at Ruthwell; it escaped injury at the time of general destruction in the sixteenth century, but the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland ordered the "many idolatrous monuments erected and made for religious worship" to be "taken down, demolished, and destroyed." It was not till two years later, however, that the cross was taken down when an Act was passed "anent the Idolatrous Monuments in Ruthwell." It was shattered, and some of the carved emblems were nearly obliterated, and in this state the rood was left where it had fallen, in the altarless church, and was used, it appears, as a bench to sit upon. Later on it was removed from the church and left out in the churchyard. But after many years, a good old minister (God rest his soul!) collected all the pieces he could find, and put them together, adding two new crossbeams (the original ones were lost), and having gaps filled in with little pieces of stone.

By-and-by there was a waking up to the importance of preserving ancient monuments (idolatrous! or not), and so the dear, beautiful old rood that had been so near to destruction, and been indeed so greatly injured, was brought into the church again, and set up near its old place. But, alas! for its old surroundings!

It is a sad story, is it not?

Shall we not pray that, one day, our old crosses may be, to all, more than "ancient monuments"?

"This stone which I have set up ... shall be called the house of God" (Gen. xxviii, 22).

To-day we shall think about some more of the great poetry that was made before the Norman Conquest, and we shall first take one of the finest and most characteristic poems which remain to us, a poem founded on Bible story; the great poem, of which we have unfortunately only a part, the "Judith."

It is not certain who wrote this poem: it may have been Cynewulf; but we do not know.

The story of Judith is a well-known one; the story of the Hebrew lady who is described in the foreword to the Book of Judith as "that illustrous woman, by whose virtue and fortitude, and armed with prayer, the children of Israel were preserved from the destruction threatened them by Holofernes and his great army."

The earlier part of the poem is lost, so we can only guess how the poet told of the ravage wrought by the general of King Nabuchodonoser in the countries close to Palestine, and how submission was as vain as resistance to a power which, for the time being, was allowed to be so terribly great.

The poem, as we have it, begins where Judith has come, in the splendour of her beauty, and the might of her purity, and the power of her faith, to destroy the destroyer and set her people free.

We have the description of the banquet, with the deep bowls and well-filled cups and pitchers borne to the sitters along the floor—just the description of the old Saxon banquet which the poet knew of. We have the drunken glee of Holofernes, his right noisy laughter and the stormy mirth that could be heard from afar; and his call to the henchmen to quit them as warriors ought, till at last they lie in their drunken sleep, powerless, and as though stricken of death.

Then comes the night, and the sending for Judith, the wise-hearted one, to Holofernes' tent. Holofernes lies in his drunken sleep, and the Lord's handmaid draws from the sheath the keen-edged glittering sword, and prays,

And then,

And she smites the evil general with the strength she had prayed for, and goes forth victorious with her handmaiden, to bear the tidings to her people of the deliverance wrought for them, ascribing the glory to God and His might. Judith leaves the camp of the Assyrians, with her waiting-woman, who carries the head of Holofernes in a bag. Men and women in great multitudes flock to the fortress-gate, pressing and running to meet God's handmaid, glad of heart to know of her home-coming. They let her in reverently, and the trophy she has brought is shown them. Judith beseeches them to go forth to the fight, as soon as the Maker of the beginning of all things, the King of high honour, hath sent the bright light from the East; to go forth bearing shield and buckler and the bright helmet, to meet the thronging foemen, and fell the folk-leaders, the doomed spear-bearers. Their foes are doomed to death, and they shall have glory and honour in battle. Then follows a great battle, with full victory to Israel.

The poet has varied from the Biblical story, in representing the officers of Holofernes' army as drunk; and also in telling of a battle after the return of Judith to Bethulia. It also may seem strange that Judith should address the Holy Trinity and each separate Person thereof. The old Christian poet carried his belief along with him, and the handmaid of God, the brave Judith, was to him a follower of Our Lord. The brave Judith, yes! St Dominic's Third Order was at first, as we know, called "The militia of Jesus Christ." How Judith would have loved the name! And we may think, may we not? how, looking from her place among the glorified, she smiled on the great warrior Maiden Saint who went in the might of the Lord, to deliver her country from the rule of the stranger.

The story of Judith would especially appeal to people living at a time when incursions of foreigners were well known, and later on, still unforgotten. Abbot Ælfric, about whose work I have to tell you something presently, in writing a short account of the Old Testament with its various books, says that the Book of Judith "is put into English in our manner as an example to you men, that you should defend your country with weapons against an invading army"—the word which he uses, "here," always meaning in old English the army of the Danes. Ælfric also wrote "a homily on Judith to teach the English the virtues of resistance to the Danes."

It is interesting likewise to think that the poet of "Judith" may have had in his mind some great Englishwoman concerning whom he wished in a veiled way to convey well-deserved praise. Perhaps he was inspired to tell of Judith, by the deeds of King Alfred's daughter, Æthelflaed, known as the Lady of the Mercians, and sought to do honour to her as well as to the great Hebrew lady.

Æthelflaed fortified Chester and other towns, and, along with King Edward, built fortresses, "chiefly along the line of frontier exposed to the Danes, as at Bridgenorth, Tamworth, Warwick, Hertford, Witham in Essex, and other places." Of course it is uncertain whether our poet was thinking of Æthelflaed. We should be able to say whether it were impossible if we knew the date of "Judith," as, if the poem were composed before Æthelflaed's time, she could not have entered into the poet's mind.