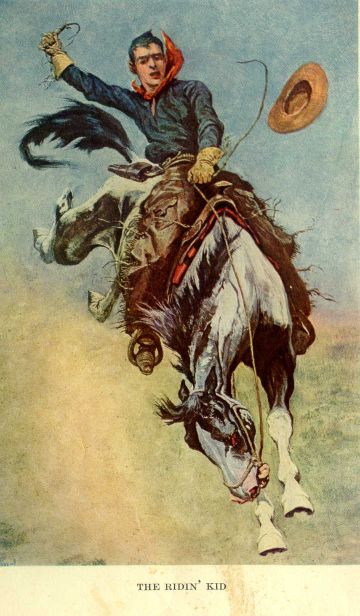

Project Gutenberg's The Ridin' Kid from Powder River, by Henry Herbert Knibbs This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Ridin' Kid from Powder River Author: Henry Herbert Knibbs Illustrator: Stanley L. Wood and R. M. Brinkerhoff Release Date: August 14, 2005 [EBook #16530] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE RIDIN' KID FROM POWDER RIVER *** Produced by Al Haines

| I. | YOUNG PETE |

| II. | FIREARMS AND NEW FORTUNES |

| III. | A WARNING |

| IV. | JUSTICE |

| V. | A CHANGE OF BASE |

| VI. | NEW VISTAS |

| VII. | PLANS |

| VIII. | SOME BOOKKEEPING |

| IX. | ROWDY—AND BLUE SMOKE |

| X. | "TURN HIM LOOSE!" |

| XI. | POP ANNERSLEY'S BOY |

| XII. | IN THE PIT |

| XIII. | GAME |

| XIV. | THE KITTY-CAT |

| XV. | FOUR MEN |

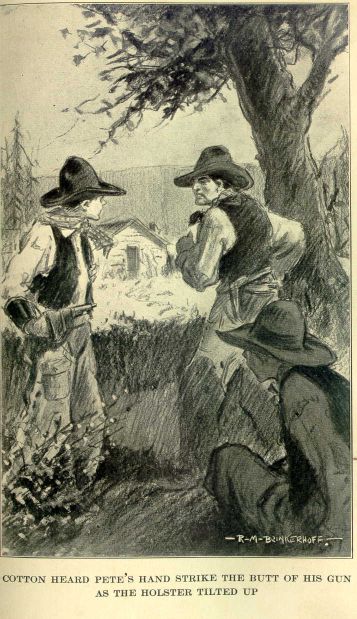

| XVI. | THE OPEN HOLSTER |

| XVII. | A FALSE TRAIL |

| XVIII. | THE BLACK SOMBRERO |

| XIX. | THE SPIDER |

| XX. | BULL MALVEY |

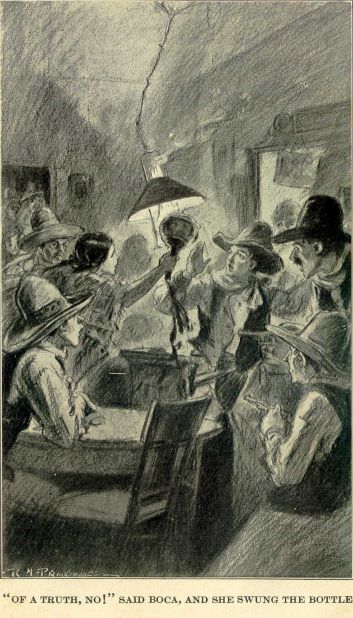

| XXI. | BOCA DULZURA |

| XXII. | "A DRESS—OR A RING—PERHAPS" |

| XXIII. | THE DEVIL-WIND |

| XXIV. | "A RIDER STOOD AT THE LAMPLIT BAR" |

| XXV. | "PLANTED—OUT THERE" |

| XXVI. | THE OLLA |

| XXVII. | OVER THE LINE |

| XXVIII. | A GAMBLE |

| XXIX. | QUERY |

| XXX. | BRENT'S MISTAKE |

| XXXI. | FUGITIVE |

| XXXII. | EL PASO |

| XXXIII. | THE SPIDER'S ACCOUNT |

| XXXIV. | DORIS |

| XXXV. | "CAUGHT IT JUST IN TIME" |

| XXXVI. | WHITE-EYE |

| XXXVII. | "CLOSE THE CASES" |

| XXXVIII. | GETTING ACQUAINTED |

| XXXIX. | A PUZZLE GAME |

| XL. | THE MAN DOWNSTAIRS |

| XLI. | "A LAND FAMILIAR" |

| XLII. | "OH, SAY TWO THOUSAND" |

| XLIII. | A NEW HAT—A NEW TRAIL |

| XLIV. | THE OLD TRAIL |

| XLV. | HOME FOLKS |

| XLVI. | THE RIDIN' KID FROM POWDER RIVER |

With the inevitable pinto or calico horse in his string the horse-trader drifted toward the distant town of Concho, accompanied by a lazy cloud of dust, a slat-ribbed dog, and a knock-kneed foal that insisted on getting in the way of the wagon team. Strung out behind this indolently moving aggregation of desert adventurers plodded an indifferent lot of cayuses, their heads lowered and their eyes filled with dust.

Young Pete, perched on a saddle much too large for him, hazed the tired horses with a professional "Hi! Yah! Git in there, you doggone, onnery, three-legged pole-cat you!" A gratuitous command, for the three-legged pole-cat referred to had no other ambition than to shuffle wearily along behind the wagon in the hope that somewhere ahead was good grazing, water, and chance shade.

The trader was lean, rat-eyed, and of a vicious temper. Comparatively, the worst horse in his string was a gentleman. Horse-trading and whiskey go arm-in-arm, accompanied by their copartners, profanity and tobacco-chewing. In the right hand of the horse-trader is guile and in his left hand is trickery. And this squalid, slovenly-booted, and sombrero'd gentleman of the outlands lived down to and even beneath all the vicarious traditions of his kind, a pariah of the waste places, tolerated in the environs of this or that desert town chiefly because of Young Pete, who was popular, despite the fact that he bartered profanely for chuck at the stores, picketed the horses in pasturage already preempted by the natives, watered the horses where water was scarce and for local consumption only, and lied eloquently as to the qualities of his master's caviayard when a trade was in progress. For these manful services Young Pete received scant rations and much abuse.

Pete had been picked up in the town of Enright, where no one seemed to have a definite record of his immediate ancestry. He was quite willing to go with the trader, his only stipulation being that he be allowed to bring along his dog, another denizen of Enright whose ancestry was as vague as were his chances of getting a square meal a day. Yet the dog, despite lean rations, suffered less than Young Pete, for the dog trusted no man. Consequently he was just out of reach when the trader wanted to kick something. Young Pete was not always so fortunate. But he was not altogether unhappy. He had responsibilities, especially when the trader was drunk and the horses needed attention. Pete learned much profanity without realizing its significance. He also learned to chew tobacco and realized its immediate significance. He mastered the art, however, and became in his own estimation a man grown—a twelve-year-old man who could swear, chew, and show horses to advantage when the trader could not, because the horses were not afraid of Young Pete.

When Pete got kicked or cuffed he cursed the trader heartily. Once, after a brutal beating, Young Pete backed to the wagon, pulled the rifle from beneath the seat, and threatened to kill the trader. After that the rifle was never left loaded. In his tough little heart Pete hated his master, but he liked the life, which offered much variety and promised no little romance of a kind.

Pete had barely existed for twelve years. When the trader came along with his wagon and ponies and cajoled Pete into going with him, Pete gladly turned his face toward wider horizons and the great adventure. Yet for him the great adventure was not to end in the trading of horses and drifting from town to town all his life.

Old man Annersley held down a quarter-section on the Blue Mesa chiefly because he liked the country. Incidently he gleaned a living by hard work and thrift. His homestead embraced the only water for miles in any direction, water that the upland cattlemen had used from time immemorial. When Annersley fenced this water he did a most natural and necessary thing. He had gathered together a few head of cattle, some chickens, two fairly respectable horses, and enough timber to build a comfortable cabin. He lived alone, a gentle old hermit whose hand was clean to every man, and whose heart was tender to all living things despite many hard years in desert and range among men who dispensed such law as there was with a quick forefinger and an uncompromising eye. His gray hairs were honorable in that he had known no wastrel years. Nature had shaped him to a great, rugged being fitted for the simplicity of mountain life and toil. He had no argument with God and no petty dispute with man. What he found to do he did heartily. The horse-trader, camped near Concho, came to realize this.

Old man Annersley was in need of a horse. One of his team had died that winter. So he unhooked the pole from the buckboard, rigged a pair of shafts, and drove to Concho, where he heard of the trader and finally located that worthy drinking at Tony's Place. Young Pete, as usual, was in camp looking after the stock. The trader accompanied Annersley to the camp. Young Pete, sniffing a customer, was immediately up and doing. Annersley inspected the horses and finally chose a horse which Young Pete roped with much swagger and unnecessary language, for the horse was gentle, and quite familiar with Young Pete's professional vocabulary.

"This here animal is sound, safe, and a child could ride him," asserted Young Pete as he led the languid and underfed pony to the wagon. "He's got good action." Pete climbed to the wagon-wheel and mounted bareback. "He don't pitch, bite, kick, or balk." The horse, used to being shown, loped a few yards, turned and trotted back. "He neck-reins like a cow-hoss," said Pete, "and he can turn in a ten-cent piece. You can rope from him and he'll hold anything you git your rope on."

"Reckon he would," said Annersley, and his eyes twinkled. "'Specially a hitchin'-rail. Git your rope on a hitchin'-rail and I reckon that hitchin'-rail would never git away from him."

"He's broke right," reasserted Young Pete. "He's none of your ornery, half-broke cayuses. You ought to seen him when he was a colt! Say, 't wa'n't no time afore he could outwork and outrun any hoss in our bunch."

"How old be you?" queried Annersley.

"Twelve, goin' on thirteen."

"Uh-huh. And the hoss?"

"Oh, he's got a little age on him, but that don't hurt him none."

Annersley's beard twitched. "He must 'a' been a colt for quite a spell. But I ain't lookin' for a cow-hoss. What I want is a hoss that I can work. How does he go in harness?"

"Harness! Say, mister, this here hoss can pull the kingpin out of a wagon without sweatin' a hair. Hook him onto a plough and he sure can make the ole plough smoke."

Annersley shook his head. "That's a mite too fast for me, son. I'd hate to have to stop at the end of every furrow and pour water on that there plough-point to keep her cool."

"'Course if you're lookin' for a cheap hoss," said Young Pete, nothing abashed, "why, we got 'em. But I was showin' you the best in the string."

"Don't know that I want him. What you say he was worth?"

"He's worth a hundred, to any man. But we're sellin' him cheap, for cash—forty dollars."

"Fifty," said the trader, "and if he ain't worth fifty, he ain't worth puttin' a halter on. Fifty is givin' him to you."

"So? Then I reckon I don't want him. I wa'n't lookin' for a present. I was lookin' to buy a hoss."

The trader saw a real customer slipping through his fingers. "You can put a halter on him for forty—cash."

"Nope. Your pardner here said forty,"—and Annersley smiled at Young Pete. "I'll look him over ag'in for thirty."

Young Pete knew that they needed money badly, a fact that the trader was apt to ignore when he was drinking. "You said I could sell him for forty, or mebby less, for cash," complained Young Pete, slipping from the pony and tying him to the wagon-wheel.

"You go lay down!" growled the trader, and he launched a kick that jolted Pete into the smouldering camp-fire. Pete was used to being kicked, but not before an audience. Moreover, the hot ashes had burned his hands. Pete's dog, hitherto asleep beneath the wagon, rose bristling, anxious to defend his young master, but afraid of the trader. The cowering dog and the cringing boy told Annersley much.

Young Pete, brushing the ashes from his over-alls, rose and shaking with rage, pointed a trembling finger at the trader. "You're a doggone liar! You're a doggone coward! You're a doggone thief!"

"Just a minute, friend," said Annersley as the trader started toward the boy. "I reckon the boy is right—but we was talkin' hosses. I'll give you just forty dollars for the hoss—and the boy."

"Make it fifty and you can take 'em. The kid is no good, anyhow."

This was too much for Young Pete. He could stand abuse and scant rations, but to be classed as "no good," when he had worked so hard and lied so eloquently, hurt more than mere kick or blow. His face quivered and he bit his lip. Old man Annersley slowly drew a wallet from his overalls and counted out forty dollars. "That hoss ain't sound," he remarked and he recounted the money. He's got a couple of wind-puffs, and he's old. He needs feedin' and restin' up. That boy your boy?"

"That kid! Huh! I picked him up when he was starvin' to death over to Enright. I been feedin' him and his no-account dog for a year, and neither of 'em is worth what he eats."

"So? Then I reckon you won't be missin' him none if I take him along up to my place."

The horse-trader did not want to lose Young Pete, but he did want Annersley's money. "I'll leave it to him," he said, flattering himself that Pete dare not leave him.

"What do you say, son?"—and old man Annersley turned to Pete. "Would you like to go along up with me and help me to run my place? I'm kind o' lonesome up there, and I was thinkin' o' gettin' a pardner."

"Where do you live?" queried Pete, quickly drying his eyes.

"Why, up in those hills, which don't no way smell of liquor and are tellin' the truth from sunup to sunup. Like to come along and give me a hand with my stock?"

"You bet I would!"

"Here's your money," said Annersley, and he gave the trader forty dollars. "Git right in that buckboard, son."

"Hold on!" exclaimed the trader. "The kid stays here. I said fifty for the outfit."

"I'm goin'," asserted Young Pete. "I'm sick o' gettin' kicked and cussed every time I come near him. He licked me with a rawhide last week."

"He did, eh? For why?"

"'Cause he was drunk—that's why!"

"Then I reckon you come with me. Such as him ain't fit to raise young 'uns."

Young Pete was enjoying himself. This was indeed revenge—to hear some one tell the trader what he was, and without the fear of a beating. "I'll go with you," said Pete. "Wait till I git my blanket."

"Don't you touch nothin' in that wagon!" stormed the trader.

"Git your blanket, son," said Annersley.

The horse-trader was deceived by Annersley's mild manner. As Young Pete started toward the wagon, the trader jumped and grabbed him. The boy flung up his arms to protect his face. Old man Annersley said nothing, but with ponderous ease he strode forward, seized the trader from behind, and shook that loose-mouthed individual till his teeth rattled and the horizon line grew dim.

"Git your blanket, son," said Annersley, as he swung the trader round, deposited him face down in the sand, and sat on him. "I'm waitin'."

"Goin' to kill him?" queried Young Pete, his black eyes snapping.

"Shucks, no!"

"Kin I kick him—jest onct, while you hold him down?"

"Nope, son. That's too much like his way. You run along and git your blanket if you're goin' with me."

Young Pete scrambled to the wagon and returned with a tattered blanket, his sole possession, and his because he had stolen it from a Mexican camp near Enright. He scurried to the buckboard and hopped in.

Annersley rose and brought the trader up with him as though the latter were a bit of limp tie-rope.

"And now we'll be driftin'," he told the other.

Murder burned in the horse-trader's narrow eyes, but immediate physical ambition was lacking.

Annersley bulked big. The horse-trader cursed the old man in two languages. Annersley climbed into the buckboard, gave Pete the lead-rope of the recent purchase, and clucked to his horse, paying no attention whatever to the volley of invectives behind him.

"He'll git his gun and shoot you in the back," whispered Young Pete.

"Nope, son. He'll jest go and git another drink and tell everybody in Concho how he's goin' to kill me—some day. I've handled folks like him frequent."

"You sure kin fight!" exclaimed Young Pete enthusiastically.

"Never hit a man in my life. I never dast to," said Annersley.

"You jest set on 'em, eh?"

"Jest set on 'em," said Annersley. "You keep tight holt to that rope. That fool hoss acts like he wanted to go back to your camp."

Young Pete braced his feet and clung to the rope, admonishing the horse with outland eloquence. As they crossed the arroyo, the led horse pulled back, all but unseating Young Pete.

"Here, you!" cried the boy. "You quit that—afore my new pop takes you by the neck and the—pants and sits on you!"

"That's the idea, son. Only next time, jest tell him without cussin'."

"He always cusses the hosses," said Young Pete. "Everybody cusses 'em."

"'Most everybody. But a man what cusses a hoss is only cussin' hisself. You're some young to git that—but mebby you'll recollect I said so, some day."

"Didn't you cuss him when you set on him?" queried Pete.

"For why, son?"

"Wa'n't you mad?"

"Shucks, no."

"Don't you ever cuss?"

"Not frequent, son. Cussin' never pitched any hay for me."

Young Pete was a bit disappointed. "Didn't you never cuss in your life?"

Annersley glanced down at the boy.

"Well, if you promise you won't tell nobody, I did cuss onct, when I struck the plough into a yellow-jacket's nest which I wa'n't aimin' to hit, nohow. Had the reins round my neck, not expectin' visitors, when them hornets come at me and the hoss without even ringin' the bell. That team drug me quite a spell afore I got loose. When I got enough dirt out of my mouth so as I could holler, I set to and said what I thought."

"Cussed the hosses and the doggone ole plough and them hornets—and everything!" exclaimed Pete.

"Nope, son, I cussed myself for hangin' them reins round my neck. What you say your name was?"

"Pete."

"What was the trader callin' you—any other name besides Pete?"

"Yes, I reckon he was. When he is good 'n' drunk he would be callin' me a doggone little—"

"Never mind, I know about that. I was meanin' your other name."

"My other name? I ain't got none. I'm Pete."

Annersley shook his head. "Well, pardner, you'll be Pete Annersley now. Watch out that hoss don't jerk you out o' your jacket. This here hill is a enterprisin' hill and leads right up to my place. Hang on! As I was sayin', we're pardners, you and me. We're goin' up to my place on the Blue and tend to the critters and git washed up and have supper, and mebby after supper we'll mosey around so you kin git acquainted with the ranch. Where'd you say your pop come from?"

"I dunno. He ain't my real pop."

Annersley turned and looked down at the lean, bright little face. "You hungry, son?"

"You bet!"

"What you say if we kill a chicken for supper—and celebrate."

"G'wan, you're joshin' me!"

"Nope. I like chicken. And I got one that needs killin'; a no-account ole hen what won't set and won't lay."

"Then we'll ring her doggone head off, eh?"

"Somethin' like that—only I ain't jest hatin' that there hen. She ain't no good, that's all."

Young Pete pondered, watching Annersley's grave, bearded face. Suddenly he brightened. "I know! Nobody kin tell when you're joshin' 'em, 'cause your whiskers hides it. Guess I'll grow some whiskers and then I kin fool everybody."

Old man Annersley chuckled, and spoke to the horses. Young Pete, happier than he had ever been, wondered if this good luck would last—if it were real, or just a dream that would vanish, leaving him shivering in his tattered blanket, and the horse-trader telling him to get up and rustle wood for the morning fire.

The buckboard topped the rise and leveled to the tree-girdled mesa. Young Pete stared. This was the most beautiful spot he had ever seen. Ringed round by a great forest of spruce, the Blue Mesa lay shimmering in the sunset like an emerald lake, beneath a cloudless sky tinged with crimson, gold, and amethyst. Across the mesa stood a cabin, the only dwelling in that silent expanse. And this was to be his home, and the big man beside him, gently urging the horse, was his partner. He had said so. Surely the great adventure had begun.

Annersley glanced down. Young Pete's hand was clutched in the old man's coat-sleeve, but the boy was gazing ahead, his bright black eyes filled with the wonder of new fortunes and a real home. Annersley blinked and spoke sharply to the horse, although that good animal needed no urging as he plodded sturdily toward the cabin.

For a few days the old man had his hands full. Young Pete, used to thinking and acting for himself, possessed that most valuable but often dangerous asset, initiative. The very evening that he arrived at the homestead, while Annersley was milking the one tame cow out in the corral, Young Pete decided that he would help matters along by catching the hen which Annersley had pointed out to him when he drove into the yard. Milking did not interest Young Pete; but chasing chickens did.

The hen, a slate-colored and maternal-appearing biddy, seemed to realize that something unusual was afoot. She refused to be driven into the coop, perversely diving about the yard and circling the out-buildings until even Young Pete's ambition flagged. Out of breath he marched to the house. Annersley's rifle stood in the corner. Young Pete eyed it longingly, finally picked it up and stole gingerly to the doorway. The slate-colored hen had cooled down and was at the moment contemplating the cabin with head sideways, exceedingly suspicious and ruffled, but standing still. Just as Young Pete drew a bead on her, the big red rooster came running to assure her that all was well—that he would protect her; that her trepidation was unfounded. He blustered and strutted, declaring himself Lord High Protector of the hen-yard and just about the handsomest thing in feathers—Bloom! Young Pete blinked, and rubbed his shoulder. The slate-colored hen sprinted for parts unknown. The big red rooster flopped once or twice and then gave up the ghost. He had strutted across the firing line just as Young Pete pulled the trigger. The cow jumped and kicked over the milk-pail. Old Annersley came running. But Young Pete, the lust of the chase spurring him on, had disappeared around the corner of the cabin after the hen. He routed her out from behind the haystack, herded her swiftly across the clearing to the lean-to stable, and corralled her, so to speak, in a manger. Just as Annersley caught up with him, Pete leveled and fired—at close range. What was left of the hen—which was chiefly feathers, he gathered up and held by the remaining leg. "I got her!" he panted.

Annersley paused to catch his breath. "Yes—you got her. Gosh-A'mighty, son—I thought you had started in to clean out the ranch! You downed my rooster and you like to plugged me an' that heifer there. The bullit come singin' along and plunked into the rain-bar'l and most scared me to death. What in the ole scratch started you on the war-path, anyhow?"

Pete realized that he had overdone the matter slightly. "Why, nothin'—only you said we was to eat that hen for supper, an' I couldn't catch the dog-gone ole squawker, so I jest set to and plugged her. This here gun of yourn kicks somethin' fierce!"

"Well, I reckon you was meanin' all right. But Gosh-A'mighty! You might 'a' killed the cow or me or somethin'!"

"Well, I got her, anyhow. I got her plumb center."

"Yes—you sure did." And the old man took the remains of the hen from Pete and "hefted" those remains with a critical finger and thumb. "One laig left, and a piece of the breast." He sighed heavily. Young Pete stared up at him, expecting praise for his marksmanship and energy. The old man put his hand on Pete's shoulder. "It's all right this time, son. I reckon you wasn't meanin' to murder that rooster. I only got one, and—"

"He jest run right in front of the hen when I cut loose. He might 'a' knowed better."

"We'll go see." And Annersley plodded to the yard, picked up the defunct rooster and entered the cabin.

Young Pete cooled down to a realization that his new pop was not altogether pleased. He followed Annersley, who told him to put the gun back in the corner.

"Got to clean her first," asserted Young Pete.

"You look out you don't shoot yourself," said Annersley from the kitchen.

"Huh," came from the ambitious, young hunter of feathered game, "I know all about guns—and this here ole musket sure needs cleanin' bad. She liked to kicked my doggone head off."

They ate what was left of the hen, and a portion of the rooster. After supper Annersley sat outside with the boy and talked to him kindly. Slowly it dawned upon Young Pete that it was not considered good form in the best families of Arizona to slay law-abiding roosters without explicit directions and permission from their owners. The old man concluded with a promise that if Young Pete liked to shoot, he should some day have a gun of his own if he, in turn, would agree to do no shooting without permission. The promise of a real gun of his own touched Young Pete's tough little heart. He stuck out his hand. The compact was sealed.

"Git a thirty-thirty," he suggested.

"What do you know about thirty-thirties?"

"Huh, I know lots. My other pop was tellin' me you could git a man with a thirty a whole heap farther than you could with any ole forty-four or them guns. I shot heaps of rabbits with his."

"Well, we'll see. But you want to git over the idee of gettin' a man with any gun. That goes with horse-tradin' and liquor and such. But we sure aim to live peaceful, up here."

Meanwhile, Young Pete, squatting beside Annersley, amused himself by spitting tobacco juice at a procession of red ants that trailed from nowhere in particular toward the doorstep.

"Makes 'em sick," he chuckled as a lucky shot dissipated the procession.

"It's sure wastin' cartridges on mighty small game," remarked Annersley.

"Don't cost nothin' to spit on 'em," said Young Pete.

"Not now. But when you git out of chewin'-tobacco, then where you goin' to git some more?"

"To the store, I reckon."

"Uh-huh. But where you goin' to git the money?"

"He was givin' me all the chewin' I wanted," said Pete.

"Uh-huh. Well, I ain't got no money for chewin'-tobacco. But I tell you what, Pete. Now, say I was to give you a dollar a week for—for your wages. And say I was to git you one of them guns like you said; you couldn't shoot chewin'-tobacco in that gun, could you?"

"Most anybody knows that!" laughed Pete.

"But you could buy cartridges with that dollar—an' shoot lots."

"Would you lick me if I bought chewin'?"

"Shucks, no! I was jest leavin' it to you."

"When do I git that dollar—the first one?"

Annersley smiled to himself. Pete was shrewd and in no way inclined to commit himself carelessly. Horse-trading had sharpened his wits to a razor-edge and dire necessity and hunger had kept those wits keen. Annersley was amused and at the same time wise enough in his patient, slow way to hide his amusement and talk with Pete as man to man. "Why, you ain't been workin' for me a week yet! And come to think—that rooster was worth five dollars—every cent! What you say if I was to charge that rooster up to you? Then after five weeks you was to git a dollar, eh?"

Pete pondered this problem. "Huh!" he exclaimed suddenly. "You et more 'n half that rooster—and some of the hen."

"All right, son. Then say I was to charge you two dollars for what you et?"

"Then, I guess beans is good enough for me. Anyhow, I never stole your rooster. I jest shot him."

"Which is correct. Reckon we'll forgit about that rooster and start fresh." The old man fumbled in his pocket and brought up a silver dollar. "Here's your first week's wages, son. What you aim to do with it?"

"Buy cartridges!" exclaimed Pete. "But I ain't got no gun."

"Well, we'll be goin' to town right soon. I'll git you a gun, and mebby a scabbard so you can carry it on the saddle."

"Kin I ride that hoss I seen out there?" queried Pete.

"What about ridin' the hoss you sold me? From what you said, I reckon they ain't no hoss can touch him, in this country."

Pete hesitated on the thin edge of committing himself, tottered and almost fell, but managed to retain his balance. "Sure, he's a good hoss! Got a little age on him, but that don't hurt none. I was thinkin' mebby you'd like that other cayuse of yours broke right. Looks to me like he needs some handlin' to make a first-class saddle-hoss."

The old man smiled broadly. Pete, like a hungry mosquito, was hard to catch.

"You kin ride him," said Annersley. "'Course, if he pitches you—" And the old man chuckled.

"Pitch me? Say, pardner, I'm a ridin' son-of-a-gun from Powder River and my middle name is 'stick.' I kin ride 'm comin' and goin'—crawl 'm on the run and bust 'm wide open every time they bit the dirt. Turn me loose and hear me howl. Jest give me room and see me split the air! You want to climb the fence when I 'm a-comin'!"

"Where did you git that little song?" queried Annersley.

"Why—why, that's how the fellas shoot her over to the round-up at Magdalena and Flag. Reckon I been there!"

"Well, don't you bust ole Apache too hard, son. He's a mighty forgivin' hoss—but he's got feelin's."

"Huh! You're a-joshin' me agin. I seen your whiskers kind o' wiggle. You think I'm scared o' that hoss?"

"Just a leetle mite, son. Or you wouldn't 'a' sung that there high-chin song. There's some good riders that talk lots. But the best riders I ever seen, jest rode 'em—and said nothin'."

"Like when you set on my other pop, eh?"

"That's the idee."

Pete, used to a rough-and-tumble existence, was deeply impressed by the old man's quiet outlook and gentle manner. While not altogether in accord with Annersley's attitude in regard to profanity and chewing tobacco—still, Young Pete felt that a man who could down the horse-trader and sit on him and suffer no harm was somehow worth listening to.

That first and unforgettable year on the homestead was the happiest year of Pete's life. Intensely active, tireless, and resourceful—as are most youngsters raised in the West—he learned to milk the tame cow, manipulate the hay-rake, distinguish potato-vines from weeds and hoe accordingly, and through observation and Annersley's thrifty example, take care of his clothing and few effects. The old man taught Pete to read and to write his own name—a painful process, for Young Pete cared nothing for that sort of education and suffered only that he might please his venerable partner. When it came to the plaiting of rawhide into bridle-reins and reatas, the handling of a rope, packing for a hunting trip, reading a dim trail when tracking a stray horse, or any of the many things essential to life in the hills, Young Pete took hold with boyish enthusiasm, copying Annersley's methods to the letter. Pete was repaid a thousand-fold for his efforts by the old man's occasional:

"Couldn't 'a' done it any better myself, pardner."

For Annersley seldom called the boy "Pete" now, realizing that "pardner" meant so much more to him.

Pete had his rifle—an old carbine, much scratched and battered by the brush and rock—a thirty-thirty the old man had purchased from a cowboy in Concho.

Pete spent most of his spare time cleaning and polishing the gun. He had a fondness for firearms that almost amounted to a passion. Evenings, when the work was done and Annersley sat smoking in the doorway, Young Pete invariably found excuse to clean and oil his gun. He invested heavily in cartridges and immediately used up his ammunition on every available target until there was not an unpunctured tin can on the premises. He was quick and accurate, finally scorning to shoot at a stationary mark and often riding miles to get to the valley level where there were rabbits and "Jacks," that he occasionally bowled over on the run. Once he shot a coyote, and his cup of happiness brimmed—for the time being.

All told, it was a most healthful and happy life for a boy, and Young Pete learned, unconsciously, to "ride, shoot, and Tell the Truth," as against "Reading, Writing, and Arithmetic," for which he cared nothing. Pete might have gone far—become a well-to-do cattleman or rancher—had not Fate, which can so easily wipe out all plans and precautions in a flash, stepped in and laid a hand on his bridle-rein.

That summer occasional riders stopped at the cabin, were fed and housed and went on their way. They came chiefly from the T-Bar-T ranch—some few from Concho, a cattle outfit of the lower country. Pete intuitively disliked these men, despite the fact that they rode excellent horses, sported gay trappings, and "joshed" with him as though he were one of themselves. His instinct told him that they were not altogether friendly to Annersley. They frequently drifted into warm argument as to water-rights and nesters in general—matters that did not interest Young Pete at the time, who failed, naturally, to grasp the ultimate meaning of the talk. But the old man never seemed perturbed by these arguments, declining, in his good-natured way, to take them seriously, and feeling secure in his own rights, as a hard-working citizen, to hold and cultivate the allotment he had earned from the Government.

The T-Bar-T outfit especially grudged him the water that they had previously used to such good advantage. This water was now under fence. To make this water available to cattle would disrupt the homestead. It was at this time that Young Pete first realized the significance of these hard-riding visitors. He was cleaning his much-polished carbine, sitting cross-legged round the corner of the cabin, when two of the chance visitors, having washed and discarded their chaps, strolled out and squatted by the doorway. Old man Annersley was at the back of the cabin preparing supper.

One of the riders, a man named Gary, said something to his companion about "running the old man out of the country."

Young Pete paused in his task.

"You can't bluff him so easy," offered the companion.

"But a thirty-thirty kin talk business," said the man Gary, and he laughed.

Pete never forgot the remark nor the laugh. Next day, after the riders had departed, he told his pop what he had heard. The old man made him repeat the conversation. He shook his head. "Mostly talk," he said.

"They dassent to start runnin' us off—dast they?" queried Young Pete.

"Mostly talk," reiterated Annersley; but Pete saw that his pop was troubled.

"They can't bluff us, eh, pop?"

"I reckon not, son. How many cartridges you got?"

Young Pete thrilled to the question. "Got ten out of the last box. You got any?"

"Some. Reckon we'll go to town to-morrow."

"To git some cartridges?"

"Mebby."

This was Young Pete's first real intimation that there might be trouble that would occasion the use of cartridges. The idea did not displease him. They drove to town, bought some provisions and ammunition, and incidentally the old man visited the sheriff and retailed the conversation that Pete had overheard.

"Bluff!" said the sheriff, whose office depended upon the vote of the cattlemen. "Just bluff, Annersley. You hang on to what you got and they won't be no trouble. I know just how far those boys will go."

"Well, I don't," said Annersley. "So I was jest puttin' what you call bluff on record, case anything happened."

The sheriff, secretly in league with the cattlemen to crowd Annersley off the range, took occasion to suggest to the T-Bar-T foreman that the old man was getting cold feet—which was a mistake, for Annersley had simply wished to keep within the law and avoid trouble if possible. Thus it happened that Annersley brought upon himself the very trouble that he had honorably tried to avoid. Let the most courageous man even seem to turn and run and how soon his enemies will take up the chase!

But nothing happened that summer, and it was not until the following spring that the T-Bar-T outfit gave any hint of their real intent. The anonymous letter was a vile screed—because it was anonymous and also because it threatened, in innuendo, to burn out a homestead held by one man and a boy.

Annersley showed the letter to Pete and helped him spell it out. Then he explained gravely his own status as a homesteader, the law which allowed him to fence the water, and the labor which had made the land his. It was typical of Young Pete that when a real hazard threatened he never said much. In this instance the boy did not know just what to do. That evening Annersley missed him and called, "What you doin', pardner?"

From the cabin—Annersley, as usual, was seated outside, smoking—came the reply: "Countin' my cartridges."

Annersley knew that the anonymous letter would be followed by some hostile act if he did not vacate the homestead. He wasted no time worrying as to what might happen—but he did worry about Young Pete. If the cattlemen raided his place, it would be impossible to keep that young and ambitious fire-eater out of harm's way. So the old man planned to take Pete to Concho the next morning and leave him with the storekeeper until the difficulty should be solved, one way or the other.

This time they did not drive to Concho, but saddled up and rode down the hill trail. And during the journey Young Pete was unusually silent, wondering just what his pop planned to do.

At the store Annersley privately explained the situation to the storekeeper. Then he told Young Pete that he would leave him there for a few days as he was "goin' over north a spell."

Young Pete studied the old man with bright, blinking eyes that questioned the truth of this statement. His pop had never lied to him, and although Pete suspected what was in the wind, he had no ground for argument. Annersley was a trifle surprised that the boy consented to stay without demur. Annersley might have known that Young Pete's very silence was significant; but the old man was troubled and only too glad to find his young partner so amenable to his suggestion. When Annersley left the store Young Pete's "So-long, pop," was as casual as sunshine, but his tough little heart was thumping with restrained excitement. He knew that his pop feared trouble and wished to face it alone.

Pete allowed a reasonable length of time to elapse and then approached the storekeeper. "Gimme a box of thirty-thirties," he said, fishing up some silver from his overall pocket.

"Where'd you get all that money, Pete?"

"Why, I done stuck up the fo'man of the T-Bar-T on pay-day and made him shell out," said Pete.

The storekeeper grinned. "Here you be. Goin' huntin'?"

"Uh-huh. Huntin' snakes."

"Honest, now! Where'd you git the change?"

"My wages!" said Young Pete proudly. "Pop is givin' me a dollar a week for helpin' him. We're pardners."

"Your pop is right good to you, ain't he?"

"You bet! And he can lick any ole bunch of cow-chasers in this country. Somebody's goin' to git hurt if they monkey with him!"

"Where 'd you get the idea anybody was going to monkey with your dad?"

Young Pete felt that he had been incautious. He refused to talk further, despite the storekeeper's friendly questioning. Instead, the boy roamed about the store, inspecting and commenting upon saddlery, guns, canned goods, ready-made clothing, and showcase trinkets, his ears alert for every word exchanged by the storekeeper and a chance customer. Presently two cowboys clumped in, joshed with the store-keeper, bought tobacco and ammunition—a most usual procedure, and clumped out again. Young Pete strolled to the door and watched them enter the adobe saloon across the way—Tony's Place—the rendezvous of the riders of the high mesas. Again a group of cowboys arrived, jesting and roughing their mounts. They entered the store, bought ammunition, and drifted to the saloon. It was far from pay-day, as Pete knew. It was also the busy season. There was some ulterior reason for so many riders assembling in town. Pete decided to find out just what they were up to.

After supper he meandered across to the saloon, passed around it, and hid in an empty barrel near the rear door. He was uncomfortable, but not unhappy. He listened for a chance word that might explain the presence of so many cowboys in town that day. Frequently he heard Gary's name mentioned. He had not seen Gary with the others. But the talk was casual, and he learned nothing until some one remarked that it was about time to drift along. They left in a body, taking the mesa trail that led to the Blue. This was significant. They usually left in groups of two or three, as their individual pleasure dictated. And there was a business-like alertness about their movements that did not escape Young Pete.

The Arizona stars were clear and keen when he crept round to the front of the saloon and pattered across the road to the store. The storekeeper was closing for the night. Young Pete, restlessly anxious to follow the T-Bar-T men, invented an excuse to leave the storekeeper, who suggested that they go to bed.

"Got to see if my hoss is all right," said Pete. "The ole fool's like to git tangled up in that there drag-rope I done left on him. Reckon I'll take it off."

"Why, your dad was tellin' me you was a reg'lar buckaroo. Thought you knew better than to leave a rope on a hoss when he's in a corral."

"I forgot," invented Pete. "Won't take a minute."

"Then I'll wait for you. Run along while I get my lantern."

The storekeeper's house was but a few doors down the street, which, however, meant quite a distance, as Concho straggled over considerable territory. He lighted the lantern and sat down on the steps waiting for the boy. From the corral back of the store came the sound of trampling hoofs and an occasional word from Young Pete, who seemed to be a long time at the simple task of untying a drag-rope. The store-keeper grew suspicious and finally strode back to the corral. His first intimation of Pete's real intent was a glimpse of the boy astride the big bay and blinking in the rays of the lantern.

"What you up to?" queried the storekeeper.

Young Pete's reply was to dig his heels into the horse's ribs. The storekeeper caught hold of the bridle. "You git down and come home with me. Where you goin' anyhow?"

"Take your hand off that bridle," blustered Young Pete.

The trader had to laugh. "Got spunk, ain't you? Now you git down and come along with me, Pete. No use you riding back to the mesa to-night. Your dad ain't there. You can't find him to-night."

Pete's lip quivered. What right had the store-keeper, or any man, to take hold of his bridle?

"See here, Pete, where do you think you're goin'?"

"Home!" shrilled Pete as he swung his hat and fanned the horse's ears. It had been many years since that pony had had his ears fanned, but he remembered early days and rose to the occasion, leaving the storekeeper in the dust and Young Pete riding for dear life to stay in the saddle. Pete's hat was lost in the excitement, and next to his rifle, the old sombrero inherited from his pop was Pete's dearest possession. But even when the pony had ceased to pitch, Pete dared not go back for it. He would not risk being caught a second time.

He jogged along up the mesa trail, peering ahead in the dusk, half-frightened and half-elated. If the T-Bar-T outfit were going to run his pop out of the country, Young Pete intended to be in at the running. The feel of the carbine beneath his leg gave him courage. Up to the time Annersley had adopted him, Pete had had to fight and scheme and dodge his way through life. He had asked no favors and expected none. His pop had stood by him in his own deepest trouble, and he would now stand by his pop. That he was doing anything especially worthy did not occur to him. Partners always "stuck."

The horse, anxious to be home, took the long grade quickly, restrained by Pete, who felt that it would be poor policy to tread too closely upon the heels of the T-Bar-T men. That they intended mischief was now only too evident. And Pete would have been disappointed had they not. Although sophisticated beyond his years and used to the hazards of a rough life, this adventure thrilled him. Perhaps the men would set fire to the outbuildings and the haystack, or even try to burn the cabin. But they would have a sorry time getting to the cabin if his pop were really there.

Up the dim, starlit trail he plodded, shivering and yet elate. As he topped the rise he thought he could see the vague outlines of horses and men, but he was not certain. That soft glow against the distant timber was real enough, however! There was no mistaking that! The log stable was on fire!

The horse fought the bit as Young Pete reined him into the timber.

Pete could see no men against the glow of the burning building, but he knew that they were there somewhere, bushed in the brush and waiting. Within a few hundred yards of the cabin he was startled by the flat crack of a rifle. He felt frightened and the blood sang in his ears. But he could not turn back now! His pop might be besieged in the cabin, alone and fighting a cowardly bunch of cow-punchers who dare not face him in the open day. But what if his pop were not there? The thought struck him cold. What would he do if he made a run for the cabin and found it locked and no one there? All at once Pete realized that it was his home and his stock and hay that were in danger. Was he not a partner in pop's homestead? Then a thin red flash from the cabin window told him that Annersley was there. Following the flash came the rip and roar of the old rifle. Concealed in the timber, Pete could see the flames licking up the stable. Presently a long tongue of yellow shot up the haystack. "The doggone snakes done fired our hay!" he cried, and his voice caught in a sob. This was too much. Hay was a precious commodity in the high country. Pete yanked out his carbine, loosed a shot at nothing in particular, and rode for the cabin on the run. "We're coming pop," he yelled, followed by his shrill "Yip! Yip! We're all here!"

Several of the outlying cow-punchers saw the big bay rear and stop at the cabin as Young Pete flung out of the saddle and pounded on the door. "It's me, pop! It's Pete! Lemme in!"

Annersley's heart sank. Why had the boy come? How did he know? How had he managed to get away?

He flung open the door and dragged Pete in.

"What you doin' here?" he challenged.

"I done lost my hat," gasped Pete. "I—I was lookin' for it."

"Your hat? You gone loco? Git in there and lay down!" And though it was dark in the cabin Young Pete knew that his pop had gestured toward the bed. Annersley had never spoken in that tone before, and Young Pete resented it.

Pete was easily led, but mighty hard to drive.

"Nothin' doin'!" said Pete. "You can't boss me 'round like that! You said we was pardners, and that we was both boss. I knowed they was comin' and I fanned it up here to tell you. I reckon we kin lick the hull of 'em. I got plenty cartridges."

Despite the danger, old man Annersley smiled as he choked back a word of appreciation for Pete's stubborn loyalty and grit. When he spoke again Pete at once caught the change in tone.

"You keep away from the window," said Annersley. "Them coyotes out there 'most like aim to rush me when the blaze dies down. Reckon they'll risk settin' fire to the cabin. I don't want to kill nobody—but—you keep back—and if they git me, you stay right still in here. They won't hurt you."

"Not if I git a bead on any of 'em!" said Young Pete, taking courage from his pop's presence. "Did you shoot any of 'em yet, pop?"

"I reckon not. I cut loose onct or twict, to scare 'em off. You keep away from the window."

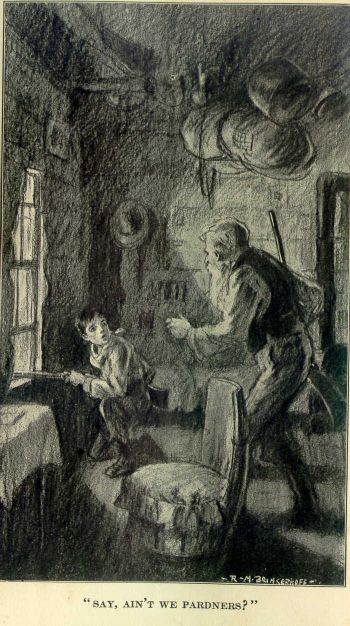

Young Pete had crept to the window and was gazing out at the sinking flames. "Say, ain't we pardners?" he queried irritably. "You said we was when you brung me up here. And pardners stick, don't they? I reckon if it was my shack that was gittin' rushed, you 'd stick, and not go bellyin' under the bunk and hidin' like a dog-gone prairie-dog."

"That's all right," said Annersley. "But there's no use takin' chances. You keep back till we find out what they're goin' to do next."

Standing in the middle of the room, well back from the southern window, the old man gazed out upon the destruction of his buildings and carefully hoarded hay. He breathed hard. The riders knew that he was in the cabin—that they had not bluffed him from the homestead. Probably they would next try to fire the cabin itself. They could crawl up to it in the dark and set fire to the place before he was aware of it. Well, they would pay high before they got him. He had fed and housed these very men—and now they were trying to run him out of the country because he had fenced a water-hole which he had every right to fence. He had toiled to make a home for himself, and the boy, he thought, as he heard Young Pete padding about the cabin. The cattlemen had written a threatening letter hinting of this, yet they had not dared to meet him in the open and have it out face to face. He did not want to kill, yet such men were no better than wolves. And as wolves he thought of them, as he determined to defend his home.

Young Pete, spider-like in his quick movements, scurried about the cabin making his own plan of battle. It did not occur to him that he might get hurt—or that his pop would get hurt. They were safe enough behind the thick logs. All he thought of was the chance of a shot at what he considered legitimate game. While drifting about the country he had heard many tales of gunmen and border raids, and it was quite evident, even to his young mind, that the man who suffered attack by a gun was justified in returning the compliment in kind. And to this end he carefully arranged his cartridges on the floor, knelt and raised the window a few inches and cocked the old carbine. Annersley realized what the boy was up to and stepped forward to pull him away from the window. And in that brief moment Young Pete's career was shaped—shaped beyond all question or argument by the wanton bullet that sung across the open, cut a clean hole in the window, and dropped Annersley in his tracks.

The distant, flat report of the shot broke the silence, fired more in the hope of intimidating Annersley than anything else, yet the man who had fired it must have known that there was but one place in the brush from where the window could be seen—and to that extent the shot was premeditated, with the possibility of its killing some one in the cabin.

Young Pete heard his pop gasp and saw him stagger in the dim light. In a flash Pete was at his side. "You hit, pop?" he quavered. There came no reply. Annersley had died instantly. Pete fumbled at his chest in the dark, called to him, tried to shake him, and then, realizing what had happened threw himself on the floor beside Annersley and sobbed hopelessly. Again a bullet whipped across the clearing. Glass tinkled on the cabin floor. Pete cowered and hid his face in his arms. Suddenly a shrill yell ripped the silence. The men were rushing the cabin! Young Pete's fighting blood swelled his pulse. He and pop had been partners. And partners always "stuck." Pete crept cautiously to the window. Halfway across the clearing the blurred hulk of running horses loomed in the starlight. Young Pete rested his carbine on the window-sill and centered on the bulk. He fired and thought he saw a horse rear. Again he fired. This was much easier than shooting deer. He beard a cry and the drumming of hoofs. Something crashed against the door. Pete whirled and fired point-blank. Before he knew what had happened men were in the cabin. Some one struck a match. Young Pete cowered in a corner, all the fight oozing out of him as the lamp was lighted and he saw several men masked with bandannas. "The old man's done for," said one of them, stooping to look at Annersley. Another picked up the two empty shells from Annersley's rifle. "Where's the kid?" asked another. "Here, in the corner," said a cowboy. "Must 'a' been him that got Wright and Bradley. The old man only cut loose twict—afore the kid come. Look at this!" And dragging Young Pete to his feet, the cowboy took the carbine from him and pointed to the three thirty-thirty shells on the cabin floor.

The men were silent. Presently one of them laughed. Despite Pete's terror, he recognized that laugh. He knew that the man was Gary, he who had once spoken of running Annersley out of the country.

"It's a dam' bad business," said one of the men. "The kid knows too much. He'll talk."

"Will you keep your mouth shut, if we don't kill you?" queried Gary.

"Cut that out!" growled another. "The kid's got sand. He downed two of us—and we take our medicine. I'm for fannin' it."

Pete, stiff with fear, saw them turn and clump from the cabin.

As they left he heard one say something which he never forgot. "Must 'a' been Gary's shot that downed the o1e man. Gary knowed the layout and where he could get a line on the window."

Pete dropped to the floor and crawled over to Annersley. "Pop!" he called again and again. Presently he realized that the kindly old man who had made a home for him, and who had been more like a real father than his earlier experiences had ever allowed him to imagine, would never again answer. In the yellow haze of the lamp, Young Pete rose and dragging a blanket from the bed, covered the still form and the upturned face, half in reverence for the dead and half in fear that those dead lips might open and speak.

Dawn bared the smouldering evidence of that dastardly attack. The stable and the lean-to, where Annersley had stored his buckboard and a few farm implements when winter came, the corral fence, the haystack, were feathery ashes, which the wind stirred occasionally as a raw red sun shoved up from behind the eastern hills. The chicken-coop, near the cabin, had not been touched by the fire. Young Pete, who had fallen asleep through sheer exhaustion, was awakened by the cackling of the hens. He jumped up. It was time to let those chickens out. Strange that his pop had not called him! He rubbed his eyes, started suddenly as he realized that he was dressed—and then he remembered…

He trembled, fearful of what he would see when he stepped into the other room. "Pop!" he whispered. The hens cackled loudly. From somewhere in the far blue came the faint whistle of a hawk. A board creaked under his foot and he all but cried out. He stole to the window, scrambled over the sill, and dropped to the ground. Through habit he let the chickens out. They rushed from the coop and spread over the yard, scratching and clucking happily. Pete was surprised that the chickens should go about their business so casually. They did not seem to care that his pop had been killed.

He was back to the cabin before he realized what he was doing. From the doorway he saw that still form shrouded in the familiar old gray blanket. Something urged him to lift a corner of the blanket and look—something stronger held him back. He tip-toed to the kitchen and began building a fire. "Pop would be gettin' breakfast," he whispered. Pete fried bacon and made coffee. He ate hurriedly, occasionally turning his head to glance at that still figure beneath the blanket. Then he washed the dishes and put them carefully away, as his pop would have done. That helped to occupy his mind, but his most difficult task was still before him. He dared not stay in the cabin—and yet he felt that he was a coward if he should leave. Paradoxically he reasoned that if his pop were alive, he would know what to do. Pete knew of only one thing to do—and that was to go to Concho and tell the sheriff what had happened. Trying his best to ignore the gray blanket, he picked up all the cartridges he could find, and the two rifles, and backed from the room. He felt ashamed of the fear that drove him from the cabin. He did not want his pop to think that he was a coward. Partners always "stuck," and yet he was running away. "Good-bye, pop," he quavered. He choked and sobbed, but no tears came. He turned and went to look for the horses.

Then he remembered that the corral fence was burned, that there had been no horses there when he went to let the chickens out. He followed horse-tracks to the edge of the timber and then turned back. The horses had been stampeded by the flames and the shooting. Pete knew that they might be miles from the cabin. He cut across the mesa to the trail and trudged down toward Concho. His eyes burned and his throat ached. The rifles grew heavy, but he would not leave them. It was significant that Pete thought of taking nothing else from the cabin, neither clothing, food, nor the money that he knew to be in Annersley's wallet in the bedroom. The sun burned down upon his unprotected head, but he did not feel it. He felt nothing save the burning ache in his throat and a hope that the sheriff would arrest the men who had killed his pop. He had great faith in the sheriff, who, as Annersley had told him, was the law. The law punished evildoers. The men who had killed pop would be hung—Pete was sure of that!

Hatless, burning with fever and thirst, he arrived at the store in Concho late in the afternoon. A friendly cowboy from the low country joshed him about his warlike appearance. Young Pete was too exhausted to retort. He marched into the store, told the storekeeper what had happened, and asked for the sheriff. The storekeeper saw that there was something gravely wrong with Pete. His face was flushed and his eyes altogether too bright. He insisted on going at once to the sheriff's office.

"Now, you set down and rest. Just stay right here and keep your eye on things out front—and I'll go get the sheriff." And the storekeeper coaxed and soothed Pete into giving up his rifles. Promising to return at once, the storekeeper set out on his errand, shaking his head gravely. Annersley had been a good man, a man who commanded affection and respect from most persons. And now the T-Bar-T men "had got him." The storekeeper was not half so surprised as he was grieved. He had had an idea that something like this might happen. It was a cattle country, and Annersley had been the only homesteader within miles of Concho. "I wonder just how much of this the sheriff knows already," he soliloquized. "It's mighty tough on the kid."

When Sheriff Sutton and the storekeeper entered the store they found Young Pete in a stupor from which he did not awaken for many hours. He was put to bed and a doctor summoned from a distant town. It would have been useless, even brutal, to have questioned Pete, so the sheriff simply took the two rifles and the cartridges to his office, with what information the storekeeper could give him. The sheriff, who had always respected Annersley, was sorry that this thing had happened. Yet he was not sorry that Young Pete could give no evidence. The cattlemen would have time to pretty well cover up their tracks. Annersley had known the risks he was running when he took up the land. The sheriff told his own conscience that "it was just plain suicide." His conscience, being the better man, told him that it was "just plain murder." The sheriff knew—and yet what could he do without evidence, except visit the scene of the shooting, hold a post-mortem, and wait until Young Pete was well enough to talk?

One thing puzzled Sheriff Sutton. Both rifles had been used. So the boy had taken a hand in the fight? Several shots must have been fired, for Annersley was not a man to suffer such an outrage in silence. And the boy was known to be a good shot. Yet there had been no news of anyone having been wounded among the raiders. Sutton was preparing to ride to the Blue and investigate when a T-Bar-T man loped up and dismounted. They talked a minute or two. Then the cowboy rode out of town. The sheriff was no longer puzzled about the two rifles having been used. The cowboy had told him that two of the T-Bar-T men had been killed. That in each instance a thirty-thirty, soft-nosed slug had done the business. Annersley's rifle was an old forty-eighty-two, shooting a solid lead bullet.

When Sheriff Button arrived at the cabin he found the empty shells on the floor, noted the holes in the window, and read the story of the raid plainly. "Annersley shot to scare 'em off—but the kid shot to kill," he argued. "And dam' if I blame him."

Later, when Young Pete was able to talk, he was questioned by the sheriff. He told of the raid, of the burning of the outbuildings, and how Annersley had been killed. When questioned as to his own share in the proceedings, Pete refused to answer. When shown the two guns and asked which was his, he invariably replied, "Both of 'em," nor could he be made to answer otherwise. Finally Sheriff Sutton gave it up, partly because of public opinion, which was in open sympathy with Young Pete, and partly because he feared that in case arrests were made, and Pete were called as a witness, the boy would tell in court more than he had thus far divulged. The sheriff thought that Pete was able to identify one or more of the men who had entered the cabin, if he cared to do so. As it was, Young Pete was crafty. Already he distrusted the sheriff's sincerity. Then, the fact that two of the T-Bar-T men had been killed rather quieted the public mind, which expressed itself as pretty well satisfied that old man Annersley's account was squared. He or the boy had "got" two of the enemy. In fact, it was more or less of a joke on the T-Bar-T outfit—they should have known better.

An inquest decided that Annersley had come to his death at the hands of parties unknown. The matter was eventually shunted to one of the many legal sidings along the single-track law that operated in that vicinity. Annersley's effects were sold at auction and the proceeds used to bury him. His homestead reverted to the Government, there being no legal heir. Young Pete was again homeless, save for the kindness of the storekeeper, who set him to work helping about the place.

In a few months Pete was seemingly over his grief, but he never gave up the hope that some day he would find the man who had killed his pop. In cow-camp and sheep-camp, in town and on the range, he had often heard reiterated that unwritten law of the outlands: "If a man tried to get you—run or fight. But if a man kills your friend or your kin—get him." A law perhaps not as definitely worded in the retailing of incident or example, but as obvious nevertheless as was the necessity to live up to it or suffer the ever-lasting scorn of one's fellows.

Some nine or ten months after the inquest Young Pete disappeared. No one knew where he had gone, and eventually he was more or less forgotten by the folk of Concho. But two men never forgot him—the storekeeper and the sheriff. One of them hoped that the boy might come back some day. He had grown fond of Pete. The other hoped that he would not come back.

Meanwhile the T-Bar-T herds grazed over Annersley's homestead. The fence had been torn down, cattle wallowed in the mud of the water-hole, and drifted about the place until little remained as evidence of the old man's patient toil save the cabin. That Young Pete should again return to the cabin and there unexpectedly meet Gary was undreamed of as a possibility by either of them; yet fate had planned this very thing—"otherwise," argues the Fatalist, "how could it have happened?"

To say that Young Pete had any definite plan when he left Concho and took up with an old Mexican sheep-herder would be stretching the possibilities. And Pete Annersley's history will have to speak for itself as illustrative of a plan from which he could not have departed any more than he could have originated and followed to its final ultimatum.

Life with the storekeeper had been tame. Pete had no horse; and the sheriff, taking him at his word, had refused to give up either one of the rifles unless Pete would declare which one he had used that fateful night of the raid. And Pete would not do that. He felt that somehow he had been cheated. Even the storekeeper Roth discouraged him from using fire-arms, fearing that the boy might some day "cut loose" at somebody without word or warning. Pete was well fed and did not have to work hard, yet his ideas of what constituted a living were far removed from the conventions of Concho. He wanted to ride, to hunt, to drive team, to work in the open with lots of elbow-room and under a wide sky. His one solace while in the store was the array of rifles and six-guns which he almost reverenced for their suggestive potency. They represented power, and the only law that he believed in.

Some time after Pete had disappeared, the store-keeper, going over his stock, missed a heavy-caliber six-shooter. He wondered if the boy had taken it. Roth did not care so much for the loss of the gun as for the fact that Pete might have stolen it. Later Roth discovered a crudely printed slip of paper among the trinkets in the showcase. "I took a gun and cartriges for my wagges. You never giv me Wages." Which was true enough, the storekeeper figuring that Pete's board and lodging were just about offset by his services. In paying Pete a dollar a week, Annersley had established a precedent which involved Young Pete's pride as a wage-earner. In making Pete feel that he was really worth more than his board and lodging, Annersley had helped the boy to a certain self-respect which Pete subconsciously felt that he had lost when Roth, the storekeeper, gave him a home and work but no pay. Young Pete did not dislike Roth, but the contrast of Roth's close methods with the large, free-handed dealings of Annersley was ever before him. Pete was strong for utility. He had no boyish sense of the dramatic, consciously. He had never had time to play. Everything he did, he did seriously. So when he left Concho at dusk one summer evening, he did not "run away" in any sense. He simply decided that it was time to go elsewhere—and he went.

The old Mexican, Montoya, had a band of sheep in the high country. Recently the sheep had drifted past Concho, and Pete, alive to anything and everything that was going somewhere, had waited on the Mexican at the store. Sugar, coffee, flour, and beans were packed on the shaggy burros. Pete helped carry the supplies to the doorway and watched him pack. The two sharp-nosed sheep-dogs interested Pete. They seemed so alert, and yet so quietly satisfied with their lot. The last thing the old Mexican did was to ask for a few cartridges. Pete did not understand just what kind he wanted. With a secretiveness which thrilled Pete clear to the toes, the old herder, in the shadowy rear of the store, drew a heavy six-shooter from under his arm and passed it stealthily to Pete, who recognized the caliber and found cartridges for it. Pete's manner was equally stealthy. This smacked of adventure! Cattlemen and sheepmen were not friendly, as Pete knew. Pete had no love for the "woolies," yet he hated cattlemen. The old Mexican thanked him and invited him to visit his camp below Concho. Possibly Pete never would have left the storekeeper—or at least not immediately—had not that good man, always willing to cater to Pete's curiosity as to guns and gunmen, told him that old Montoya, while a Mexican, was a dangerous man with a six-gun; that he was seldom molested by the cattlemen, who knew him to be absolutely without fear and a dead shot.

"Huh! That old herder ain't no gun-fighter!" Pete had said, although he believed the storekeeper. Pete wanted to hear more.

"Most Mexicans ain't," replied Roth, for Pete's statement was half a challenge, half a question. "But José Montoya never backed down from a fight—and he's had plenty."

Pete was interested. He determined to visit Montoya's camp that evening. He said nothing to Roth, as he intended to return.

Long before Pete arrived at the camp he saw the tiny fire—a dot of red against the dark—and he heard the muffled trampling of the sheep as they bedded down for the night. Within a few yards of the camp the dogs challenged him, charging down the gentle slope to where he stood. Pete paid no attention to them, but marched up to the fire. Old Montoya rose and greeted him pleasantly. Another Mexican, a slim youth, bashfully acknowledged Pete's presence and called in the dogs. Pete, who had known many outland camp-fires, made himself at home, sitting cross-legged and affecting a mature indifference. The old Mexican smoked and studied the youngster, amused by his evident attempt to appear grown-up and disinterested.

"That gun, he poke you in the rib, hey?"—and Montoya chuckled.

Pete flushed and glanced down at the half-concealed weapon beneath his arm. "Tied her on with string—ain't got no shoulder holster," Pete explained in an offhand way.

"What you do with him?" The old Mexican's deep-set eyes twinkled. Pete studied Montoya's face. This was a direct but apparently friendly query. Pete wondered if he should answer evasively or directly. The fact was that he did not know just why he had taken the gun—or what he intended to do with it. After all, it was none of Montoya's business, yet Pete did not wish to offend the old man. He wanted to hear more about gun-fights with the cattlemen.

"Well, seein' it's you, señor,"—Pete adopted the grand air as most befitting the occasion,—"I'm packin' this here gun to fight cow-punchers with. Reckon you don't know some cow-punchers killed my dad. I was just a kid then. [Pete was now nearly fourteen.] Some day I'm goin' to git the man what killed him."

Montoya did not smile. This muchacho evidently had spirit. Pete's invention, made on the spur of the moment, had hit "plumb center," as he told himself. For Montoya immediately became gracious, proffered Pete tobacco and papers, and suggested coffee, which the young Mexican made while Pete and the old man chatted. Pete was deeply impressed by his reception. He felt that he had made a hit with Montoya—and that the other had taken him seriously. Most men did not, despite the fact that he was accredited with having slain two T-Bar-T cowboys. A strange sympathy grew between this old Mexican and the lean, bright-eyed young boy. Perhaps Pete's swarthy coloring and black eyes had something to do with it. Possibly Pete's assurance, as contrasted with the bashfulness and timidity of the old Mexican's nephew, had something to do with Montoya's immediate friendliness. In any event, the visit ended with an invitation to Pete to become a permanent member of the sheep-camp, Montoya explaining that his nephew wanted to go home; that he did not like the loneliness of a herder's life.

Pete had witnessed too many horse-trades to accept this proposal at once. His face expressed deep cogitation, as he flicked the ashes from his cigarette and shook his head. "I dunno. Roth is a pretty good boss. 'Course, he ain't no gun-fighter—and that's kind of in your favor—"

"What hombre say I make fight with gun?" queried Montoya.

"Why, everybody! I reckon they's mighty few of 'em want to stack up against you."

Montoya frowned. "I don' talk like that," he said, shrugging his shoulders.

Pete felt that he was getting in deep—but he had a happy inspiration. "You don't have to talk. Your ole forty-four does the talking I reckon."

"You come and cook?" queried Montoya, coming straight to the point.

"I dunno, amigo. I'll think about it."

"Bueno. It is dark, I will walk with you to Concho."

"You think I'm a kid?" flared Pete. "If was dark when I come over here and it ain't any darker now. I ain't no doggone cow-puncher what's got to git on a hoss afore he dast go anywhere."

Montoya laughed. "You come to-morrow night, eh?"

"Reckon I will."

"Then the camp will be over there—in the cañon. You will see the fire."

"I'll come over and have a talk anyway," said Pete, still unwilling to let Montoya think him anxious. "Buenos noches!"

Montoya nodded. "He will come," he said to his nephew. "Then it is that you may go to the home. He is small—but of the very great courage."

The following evening Pete appeared at the herder's camp. The dogs ran out, sniffed at him, and returned to the fire. Montoya made a place for him on the thick sheepskins and asked him if he had eaten. Yes, he had had supper, but he had no blankets. Could Montoya let him have a blanket until he had earned enough money to buy one?

The old herder told him that he could have the nephew's blankets; Pedro was to leave camp next day and go home. As for money, Montoya did not pay wages. Of course, for tobacco, or a coat or pants, he could have the money when he needed them.

Pete felt a bit taken aback. He had burnt his bridges—he could not return to Concho—yet he wanted a definite wage. "I kin pack—make and break camp—and sure cook the frijoles. Pop learned me all that; but he was payin' me a dollar a week. He said I was jest as good as a man. A dollar a week ain't much."

The old herder shook his head. "Not until I sell the wool can I pay."

"When do you sell that wool?"

"When the pay for it is good. Sometimes I wait."

"Well, I kin see where I don't get rich herdin' sheep."

"We shall see. Perhaps, if you are a good boy—"

"You got me wrong, señor. Roth he said I was the limit—and even my old pop said I was a tough kid. I ain't doin' this for my health. I hooked up with you 'cause I kinda thought—"

"Si?"

"Well, Roth was tellin' as how you could make a six-gun smoke faster than most any hombre a-livin'. Now, I was figurin' if you would show me how to work this ole smoke-wagon here"—and Pete touched the huge lump beneath his shirt—"why, that would kinda be like wages—but I ain't got no money to buy cartridges."

"I, José de la Crux Montoya, will show you how to work him. It is a big gun for such a chico."

"Oh, I reckon I kin hold her down. When do we start the shootin' match?"

Montoya smiled.

"Mañana, perhaps."

"Then that's settled!" Pete heaved a sigh. "But how am I goin' to git them cartridges?"

"From the store."

"That's all right. But how many do I git for workin' for you?"

Montoya laughed outright. "You will become a good man with the sheep. You will not waste the flour and the beans and the coffee and the sugar, like Pedro here. You will count and not say—'Oh, I think it's so much'—and because of that I will buy you two boxes of cartridges."

"Two boxes—a hundred a month?"

"Even so. You will waste many until you learn."

"Shake!" said Pete. "That suits me! And if any doggone ole brush-cats or lion or bear come pokin' around this here camp, we'll sure smoke 'em up. And if any of them cow-chasers from the mountain or the Concho starts monkeyin' with our sheep, there's sure goin' to be a cowboy funeral in these parts! You done hired a good man when you hired me!"

"We shall see," said Montoya, greatly amused. "But there is much work to be done as well as the shooting."

"I'll be there!" exclaimed Pete. "What makes them sheep keep a-moanin' and a-bawlin' and a-shufflin' round? Don't they never git to sleep?"

"Si, but it is a new camp. To-morrow night they will be quiet. It is always so."

"Well, they sure make enough noise. When do we git goin'?"

"Pedro, he will leave mañana. In two days we will move the camp."

"All right. I don't reckon Roth would be lookin' for me in any sheep-camp anyhow." Young Pete was not afraid of the storekeeper, but the fact that he had taken the gun troubled him, even though he had left a note explaining that he took the gun in lieu of wages. He shared Pedro's blankets, but slept little. The sheep milled and bawled most of the night. Even before daybreak Pete was up and building a fire. The sheep poured from the bedding-ground and pattered down to the cañon stream. Later they spread out across the wide cañon-bottom and grazed, watched by the dogs.

Full-fed and happy, Young Pete helped Pedro clean the camp-utensils. The morning sun, pushing up past the cañon-rim, picked out the details of the camp one by one—the smouldering fire of cedar wood, the packs, saddles and ropes, the water-cask, the lazy burros waiting for the sun to warm them to action, the blankets and sheepskin bedding, and farther down the cañon a still figure standing on a slight rise of ground and gazing into space—the figure of José de la Crux Montoya, the sheep-herder whom Roth had said feared no man and was a dead shot.

Pete knew Spanish—he had heard little else spoken in Concho—and he thought that "Joseph of the Cross" was a strange name for a recognized gunman. "But Mexicans always stick crosses over graves," soliloquized Pete. "Mebby that's why he's got that fancy name. Gee! But this sure beats tendin' store!"