TITIAN. ACADEMY, VENICE

VIRGIN. FROM ASSUMPTION OF THE VIRGIN.

TITIAN. ACADEMY, VENICE

VIRGIN. FROM ASSUMPTION OF THE VIRGIN.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Barbara's Heritage, by Deristhe L. Hoyt

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Barbara's Heritage

Young Americans Among the Old Italian Masters

Author: Deristhe L. Hoyt

Illustrator: Homer W. Colby

Release Date: July 7, 2005 [EBook #16241]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BARBARA'S HERITAGE ***

Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Josephine Paolucci and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

TITIAN. ACADEMY, VENICE

VIRGIN. FROM ASSUMPTION OF THE VIRGIN.

TITIAN. ACADEMY, VENICE

VIRGIN. FROM ASSUMPTION OF THE VIRGIN.

AUTHOR OF

"The World's Painters"

THIRD EDITION.

BOSTON AND CHICAGO

W.A. WILDE COMPANY

By W.A. Wilde Company.

All rights reserved.

BARBARA'S HERITAGE.

| CHAPTER | PAGE |

| I. The Unexpected Happens | 13 |

| II. Across Two Oceans | 29 |

| III. In Beautiful Florence | 45 |

| IV. A New Friend Appears | 61 |

| V. Straws show which Way the Wind Blows | 77 |

| VI. Lucile Sherman | 93 |

| VII. A Startling Disclosure | 107 |

| VIII. Howard's Questionings | 123 |

| IX. The Coming-out Party | 139 |

| X. The Mystery unfolds to Howard | 157 |

| XI. On the Way to Rome | 171 |

| XII. Robert Sumner fights a Battle | 189 |

| XIII. Cupid Laughs | 205 |

| XIV. A Visit to the Sistine Chapel | 221 |

| XV. A Morning in the Vatican | 239 |

| XVI. Poor Barbara's Trouble | 259 |

| XVII. Robert Sumner is Imprudent | 279 |

| XVIII. In Venice | 299 |

| XIX. In a Gondola | 317 |

| XX. Return from Italy | 335 |

| Epilogue: Three Years After | 355 |

| Virgin. From Assumption of the Virgin. Titian. | |

| Academy, Venice | Frontispiece |

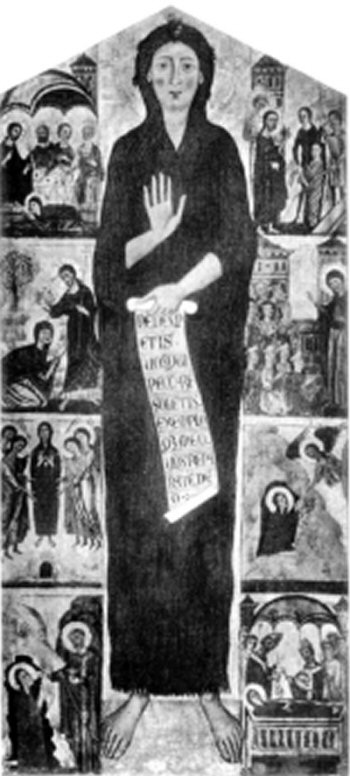

| Byzantine Magdalen. | |

| Academy, Florence | 58 |

| Group of Angels. From Coronation of the Virgin. Fra Angelico. | |

| Uffizi Gallery, Florence | 112 |

| Coronation of the Virgin. Botticelli. | |

| Uffizi Gallery, Florence | 146 |

| Head of Madonna. Perugino. | |

| Uffizi Gallery, Florence | 186 |

| The Delphian Sibyl. Michael Angelo. | |

| Sistine Chapel, Rome | 226 |

| Saint Cecilia. Raphael. | |

| Academy, Bologna | 296 |

| Marriage of Saint Catherine. Luini. | |

| Poldi-Pezzoli Museum, Milan | 350 |

| Barbara's Home | 15 |

| A Bit of Genoa | 31 |

| Church of the Annunziata, Florence | 47 |

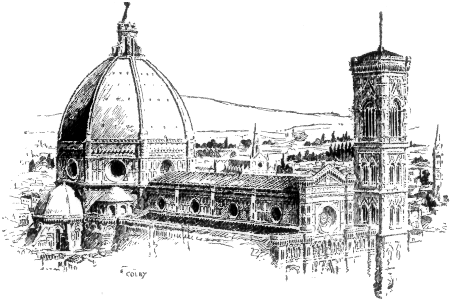

| Duomo and Campanile, Florence | 63 |

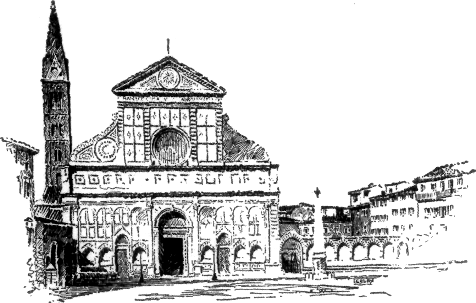

| Santa Maria Novella, Florence | 79 |

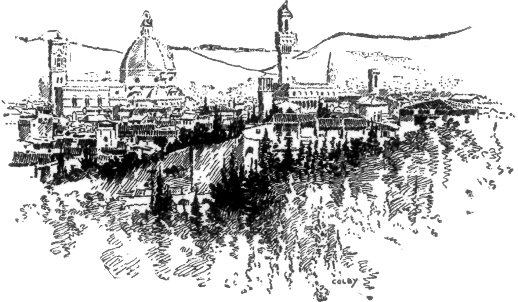

| A Glimpse of Florence | 95 |

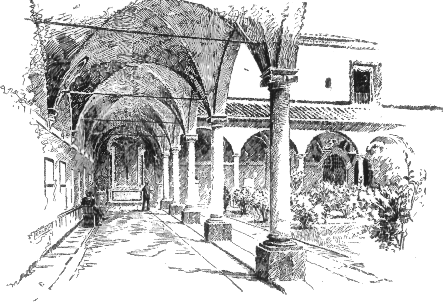

| Cloister, Museum of San Marco, Florence | 109 |

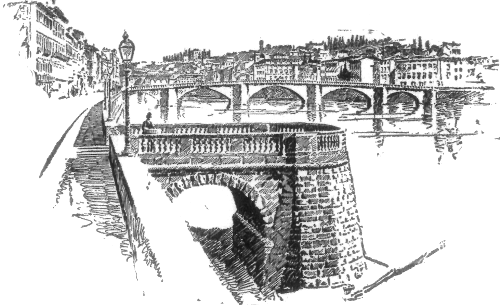

| Ponte Alla Carraja, Florence | 125 |

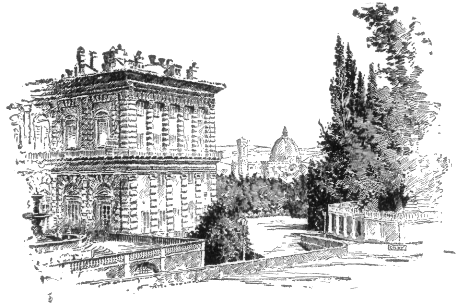

| Palazzo Pitti, Florence | 141 |

| San Miniato al Monte, Florence | 159 |

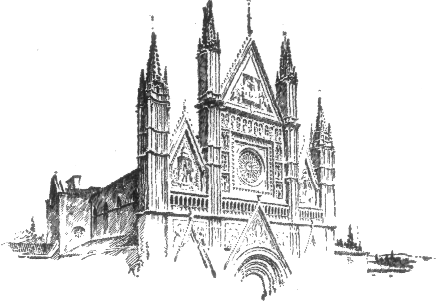

| Orvieto Cathedral | 173 |

| San Francesco, Assisi | 191 |

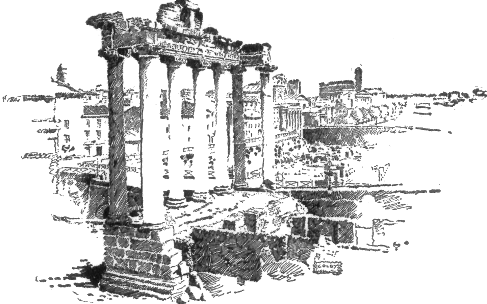

| Ruins of Forum, Rome | 207 |

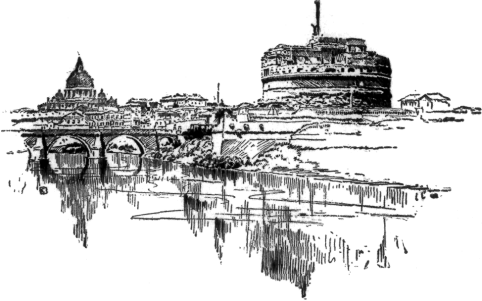

| Saint Peter's and Castle of Saint Angelo, Rome | 223 |

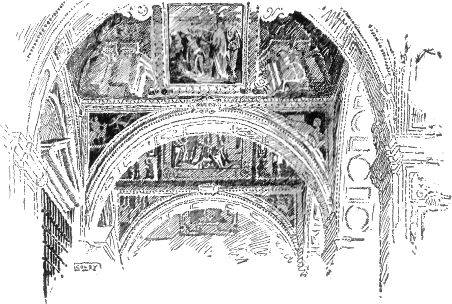

| Loggia of Raphael, Vatican, Rome | 241 |

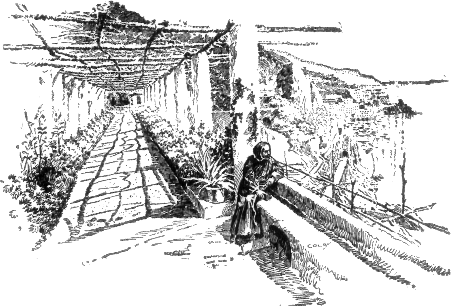

| A Bit of Amalfi | 261 |

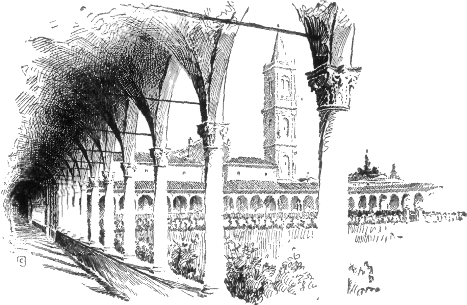

| Campo Santo, Bologna | 281 |

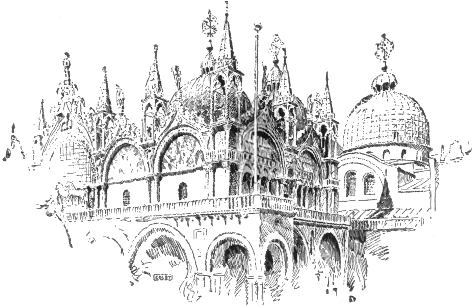

| San Marco, Venice | 301 |

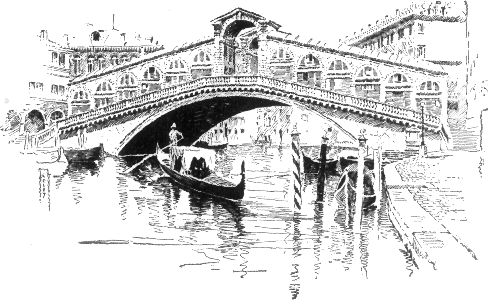

| Grand Canal and Rialto, Venice | 319 |

| Milan Cathedral | 337 |

BARBARA'S HOME.

BARBARA'S HOME.

"O Barbara! do you think papa and mamma will let us go? Can they afford it? Just to think of Italy, and sunshine, and olive trees, and cathedrals, and pictures! Oh, it makes me wild! Will you not ask them, dear Barbara? You are braver than I, and can talk better about it all. How can we bear to have them say 'no'—to give up all the lovely thought of it, now that once we have dared to dream of its coming to us—to you and me, Barbara?" and color flushed the usually pale cheek of the young girl, and her dark eyes glowed with feeling as she hugged tightly the arm of her sister.

Barbara and Bettina Burnett were walking through a pleasant street in one of the suburban towns of Boston after an afternoon spent with friends who were soon to sail for Italy.

It was a charming early September evening, and the sunset glow burned through the avenue of elm trees, beneath which the girls were passing, flooding the way with rare beauty. But not one thought did they now give to that which, ordinarily, would have delighted them; for Mrs. Douglas had astonished them that afternoon by a pressing invitation to accompany herself, her son, and daughter on this journey. For hours they had talked over the beautiful scheme, and were to present Mrs. Douglas's request to their parents that very night.

Mrs. Douglas, a wealthy woman, had been a widow almost ever since the birth of her daughter, who was now a girl of fifteen. Malcom, her son, was three or four years older. An artist brother was living in Italy, and a few years previous to the beginning of our story, Mrs. Douglas and her children had spent some months there. Now the brother was desirous that they should again go to him, especially since his sister was not strong, and it would be well for her to escape the inclemency of a New England winter.

Barbara and Bettina,—Bab and Betty, as they were called in their home,—twin daughters of Dr. Burnett, were seventeen years old, and the eldest of a large family. The father, a great-hearted man, devoted to his noble profession, and generous of himself, his time, and money, had little to spare after the wants of his family had been supplied, so it was not strange that the daughters, on sober second thought, should feel that the idea of such a trip to the Old World as Mrs. Douglas suggested could be only the dream of a moment, from which an awakening must be inevitable.

But they little knew the wisdom of Mrs. Douglas, nor for a moment did they suspect that for weeks before she had mentioned the matter to them, she and their parents had spent many hours in planning and contriving so that it might seem possible to give this great pleasure and means of education to their daughters.

Even now, while they were hesitating to mention the matter, it was already settled. Their parents had decided that, with the aid of a portion of a small legacy which Mrs. Burnett had sacredly set aside for her children, to be used only when some sufficient reason should offer, enough money could be spared during the coming year to allow them to accompany Mrs. Douglas.

As the sisters drew near the rambling, old-fashioned house, set back from the street, which was their home, a pleasant welcome awaited them. The father, who had just come from the stable to the piazza, the mother and younger children,—Richard, Lois, Margaret, and little Bertie,—and even the old dog, Dandy,—each had an affectionate greeting.

A quick look of intelligence passed between the parents as they saw the flushed faces of their daughters, which so plainly told of unusual excitement of feeling; but, saying nothing, they quietly led the way into the dining room, where all gathered around the simple supper which even the youngest could enjoy.

After the children had been put to bed, and the older ones of the family were in the library, which was their evening sitting room, Bettina looked anxiously at Barbara, who, after several attempts, succeeded in telling the startling proposition which Mrs. Douglas had made, adding that she should not dare to speak of it had she not promised Mrs. Douglas to do so.

Imagine, if you can, the amazement, the flood of joyous surprise that the girls felt as they realized, first, that to their parents it was not a new, startling subject which could not for a moment be entertained; then, that it was not only to be thought of, but planned for; and more, that the going to Italy with Mrs. Douglas, Malcom, and Margery was to be a reality, an experience that very soon would come into their lives, for they were to sail in three weeks.

After the hubbub of talk that followed, it was a very subdued and quiet pair of girls who kissed father and mother good night and went upstairs to the room in which they had slept ever since their childhood. The certain nearness of the first home-breaking, of the first going away from their dear ones, and a new conception of the tenderness of the parents, who were sacrificing so much for them, had taken such possession of their hearts that they were too full for words. For Barbara and Bettina were dear, thoughtful daughters and sisters, who had early learned to aid in bearing the family burdens, and whose closest, strongest affections were bound about the home and its dear ones.

Such busy days followed! Such earnest conferences between Mrs. Burnett and Mrs. Douglas, who was an old traveller, and knew all the ins and outs of her dear doctor's household!

It was finally decided that the dark blue serge gowns that had been worn during the last spring and on cold summer days with the warm spring jackets, would be just the thing for the girls on the steamship; that the pretty brown cloth suits which were even then in the dressmaker's hands could be worn almost constantly after reaching Italy for out-of-door life; while the simple evening gowns that had done duty at schoolgirl receptions would answer finely for at-home evenings. So that only two or three extra pairs of boots (for nothing abroad can take the place of American boots and shoes), some silk waists, so convenient for easy change of costume, and a little addition to the dainty underclothing were all that was absolutely needed.

Busy fingers soon accomplished everything necessary, and in a few swiftly passing days the trunks were packed, the tearful good-bys spoken, and the little party was on its way to New York, to sail thence for Genoa on the Kaiser Wilhelm II. of the North German Lloyd line of steamships.

Dr. Burnett had managed to accompany them thus far, and now, as the great ship is slowly leaving the wharf, and Mrs. Douglas, Malcom, Margery, Barbara, and Bettina are clustered together on her deck, waving again and again their good-bys, and straining their eyes still to recognize the dear familiar form and face among the crowd that presses forward on the receding pier, we will take time for a full introduction of the chief personages of our story.

Mrs. Douglas, who stands between her children, Malcom's arm thrown half-protectingly about her shoulders, was, or rather is (for our tale is of recent date and its characters are yet living), a rare woman. Slender and graceful, clothed in widow's dress, her soft gray hair framing a still fair and youthful face, she looks a typical American woman of refinement and culture. And she is all this, and more; for did she not possess a strong Christian character, wise judgment, and a warm motherly heart, and were she not ever eager to gain that which is noblest and best both for herself and her children from every experience of life, careful Dr. and Mrs. Burnett would never have intrusted their daughters to her.

Her husband had been a young Scotchman, well-born, finely educated, and possessed of ample means, whom she had met when a girl travelling abroad with her parents, and her brief wedded life had been spent in beautiful Edinburgh, her husband's native city. Very soon after Margery's birth came the terrible grief of her husband's death, and lonely Elizabeth Douglas came across the sea, bringing her two fatherless children to make a home for herself and them among her girlhood friends.

Malcom, a well-developed, manly young fellow, has just graduated from the Boston Latin School. As he stands beside his mother we see the military drill he has undergone in his fine carriage, straight shoulders, and erect head. He has the Scotch complexion, an abundance of fair hair, and frank, steady eyes that win him the instant trust and friendship of all who look into them. Though full of a boy's enthusiasm and fun, yet he seems older than he is, as is usually the case with boys left fatherless who early feel a certain manly responsibility for the mother and sisters.

Proud and fond indeed is Malcom Douglas of his mother and "little Madge," as he calls her, who, petite and slender, with sunny, flowing curls, the sweetest of blue eyes, and a pure, childlike face, stands, with parted lips, flushed with animation, by her mother's side. Margery is, as she looks, gentle and lovable. Not yet has she ever known the weight of the slightest burden of care, but has been as free and happy as the birds, as she has lived in her beautiful home with her mother and brother.

Barbara and Bettina stand a little apart from the others, with clasped hands and dim eyes, as the shore, the home-shore, is fast receding from their sight. They are alike, and yet unlike. People always say "Barbara and Bettina," never "Bettina and Barbara." They are of the same height, each with brown hair and eyes.

Barbara's figure is a little fuller and more womanly, her hair has caught the faintest auburn hue, her eyes have a more brilliant sparkle, and the color on her cheeks glows more steadily. She looks at strangers with a quiet self-possession, and questions others rather than thinks of herself being questioned. As a child she always fought her own and her sister's battles, and would do the same to-day did occasion demand.

Bettina is more timid and self-conscious; her dreamy eyes and quickly coming and going color betray a keen sensitiveness to thought and impressions.

Both are beautiful, and more than one of their fellow-passengers look at the sisters with interest as they stand together, so absorbed in feeling that they take no note of what is passing about them. Just now both are thinking of the same thing—a conversation held with their father as the trio sat in a corner of the car just before reaching New York.

Dr. Burnett had explained to them just how he had been enabled to meet the expense of their coming travel.

Then he said:—

"Now girls, you are, for the first time in your lives, to be away from the care and advice of your parents. Of course, if you need help in judging of anything, you are free to go to Mrs. Douglas; but there will be much that it will be best for you to decide without troubling her. You will meet all sorts of people, travellers like yourselves, and many you will see who are spending money freely and for what seems pleasure only, without one thought of the special education that travel in the Old World might bring them. Your mother and I have always been actuated by one purpose regarding our children. We cannot give you money in abundance, but we are trying to give you a liberal education,—that which is to us far superior to mere money riches,—and the only consideration that makes us willing to part from you and to sacrifice for you now, is our belief that a rare opportunity for gaining culture and an education that cannot be found at home is open to you.

"Think of this always, my daughters. Ponder it over while you are gone, and do your best to come home bringing a new wealth of knowledge that shall bless your younger brothers and sisters and our whole household, as well as your own lives. You are not going on a pleasure trip, dear girls, but to another school,—a thoroughly novel and delightful one,—but do not forget that, after all, it is a school."

As the rapidly increasing distance took from them the last sight of the father's form, Barbara and Bettina turned and looked at each other with tearful eyes; and the unspoken thought of one was, "We will come home all that you long for us to be, dear papa!" and of the other, "Oh, I do hope we shall understand what you wish, and learn what and wherever we can!" and both thoughts meant the same thing and bore the same earnest purpose.

"Come girls," said Mrs. Douglas, who had keenly observed them without appearing to do so, "it is best for us all to go to our staterooms directly and unpack our steamer-trunks. Perhaps in even an hour or two we may not feel so much like doing it as we do now."

As they passed through the end of the dining-saloon, whose tables were laden with bouquets of fresh and fragrant flowers, brought by loving friends to many of the passengers, Malcom's quick eye spied a little pile of letters on the end of a corner table.

"I wonder," said he, as he turned back to look them over, "if anybody thought to write to us."

Returning with an envelope in his hands, he cried:—

"What will you give for a letter from home already, Barbara and Betty?"

"For us!" exclaimed the girls, "a letter from home for us! Why, we never thought such a thing could be! How did it get here? Did papa bring one and put it here?"

But no, for the letter addressed in the dear mother's handwriting was clearly stamped, and its appearance testified that it had come through the mail to New York.

Hurrying to their stateroom and sitting close to each other on the sofa under the port-hole, they read Mrs. Burnett's bright, sweet motherly letter, and a note from each of their brothers and sisters,—even a crumpled printed one from five-year-old Bertie. So bright and jolly were they all, that they allayed rather than heightened the first homesick feelings, and very soon the girls were chattering happily as they busied themselves with their unpacking.

The staterooms of the Kaiser Wilhelm II. are more commodious than can be found in most steamships, even those of the same line. It was delightful to find a small wardrobe in which to hang the warm wrappers so useful on shipboard, and the thick coats that might be needed, and a chest of drawers for underclothing, gloves, etc. Toilet articles were put on the tiny wall-shelves; magazines and books on the top of the chest of drawers; and soon the little room took on a bit of an individual and homelike look which was very pleasing.

Mrs. Douglas and Margery were just opposite them, and Malcom close at hand, so there was no chance of feeling too much adrift from the old life.

"Hello, girls! Are you ready to come upstairs?" in Malcom's voice.

"How nice your room looks!" cried Margery; and up to the deck they trooped to find that Malcom had seen that their steamer-chairs were well placed close together, and that Mrs. Douglas was already tucked in under her pretty Scotch rug.

How strange the deck looked now that the host of friends that had crowded to say good-by were gone! Already many hats and bonnets had been exchanged for caps, for the wind was fresh, and, altogether, both passengers and deck struck our party as wearing quite a ship-shape air. Mrs. Douglas held in her hand a passenger-list, so interesting at just this time, and was delighted to learn that an old-time travelling companion was on board.

"But, poor woman," said she, "she always has to spend the first three or four days in her berth, so I shall not see her for a time unless I seek her there. She is a miserable sailor."

"Oh, dear!" said Bettina, "I had forgotten that there is such a thing as seasickness. Do you think, Mrs. Douglas, that Barbara and I shall be seasick? It seems impossible when we feel so well now; and the air is so fine, and everything so lovely! Are you always seasick, and Malcom, and Margery?"

"I have never been really sick, save once, when crossing the English Channel," replied Mrs. Douglas; "neither has Malcom ever given up to it, though sometimes he has evidently suffered. But poor Margery has been very sick, and it is difficult for her to exert enough will-power to quickly overcome it. It requires a prodigious amount to do this if one is really seasick."

"I wonder what it feels like," said Barbara. "I think if will-power can keep one from it, I will not be seasick."

"Come and walk, girls," called Margery, who, with Malcom, had been vigorously walking to and fro on the wide deck, while their mother, Barbara, and Bettina had been talking.

So they walked until lunch-time, and then enjoyed hugely the novelty of the first meal on shipboard. After this, the young people went aft to look down upon the steerage passengers, and forward to the bow of the noble ship, while Mrs. Douglas took her little nap downstairs.

But alas! as the steamship took her course further into the open sea, and the wind grew more and more fresh, the three girls sank into their chairs, grew silent, and before dinner-time were among the great suffering company that every ship carries during the first days and nights of her voyage.

A BIT OF GENOA

A BIT OF GENOA

"Betty!" called Barbara.

"What, dear?" answered a weak voice from the berth below.

"Do you know how much more quiet the water is? and, Betty, I think Mrs. Douglas looked really disappointed when she saw us still immovable in our berths."

It was the third morning at sea. The fresh wind of the first afternoon had blown a gale before morning. A storm followed, and for two days the larger part of the passengers had been absent from saloon and deck.

Among these were Barbara, Bettina, and Margery. Mrs. Douglas and Malcom had done their best to keep up the spirits of their little party, but had found it difficult. Now for the third time they had gone to breakfast alone.

Barbara was thinking hard; and, as she thought, her courage rose.

"Betty," said she again, "perhaps if you and I can get up and dress, it may help Margery to try, and you know how much her mother wishes her to do so, she so soon loses strength. And Mrs. Douglas is so good to you and me! I wonder if we can take the salt-water baths that she thinks help one so much on the sea. You remember how much pains she took as soon as we came on board to get all our names on the bath-stewardess's list for morning baths!"

"I believe I will try!" added she, after a long silence.

And when the broad-faced, smiling stewardess came to see if the young ladies would like anything, Barbara gladdened her heart by saying she would have her bath.

"Oh, Betty, Betty dear! you have no idea how nice it is! The ship is quiet, the port is open in the bath-room, and it is just lovely to breathe the fresh air. Do try it. I feel like a new girl!"

Before another hour had passed the girls said good-by to poor Margery after having greatly encouraged her spirits, and climbed the stairs to the deck, where they found Malcom just tucking his mother into her chair after their breakfast and morning walk on the deck. Such a bright smile as Mrs. Douglas gave them! It more than repaid for all the effort they had made.

"You are just bricks!" cried Malcom, with a joyous look. "No more seasickness! Now we will have jolly times, just so soon as Madge can come up."

"Go down and persuade her, Malcom, after you have told the deck-steward to bring some breakfast for these girls. I will help her dress, and you can bring her up in your arms if she is too weak to walk."

Before noon, Margery, looking frail as a crushed white lily, lay on a chair heaped with cushions and rugs close beside her mother; and the sweet salt air and sunshine did their best to atone for the misery that had been inflicted by the turbulent sea.

Bright, happy days followed, and sunsets and moonlight evenings, and the girls learned to love sea life. They roamed over every part of the ship. The good captain always had a smile and welcome for young people, and told them many things about the management of vessels at sea.

There was no monotony, but every day seemed full of interest. All the wonders of the great deep were about them—strange fish, sea porpoise, and whales, by day, and ever-new phosphorescent gleams and starry heavens by night. Then the wonderful interest of a sail at sea, or a distant steamship; some other humanity than that on their own ship passing them on the limitless ocean!

On the sixth day out the ship passed between Flores and Corvo, two of the northernmost islands of the Azores; and, through the glass, they could easily see the little Portuguese homes—almost the very people—scattered on the sloping hill-sides.

After two days more, the long line of the distant shore of Cape St. Vincent came into view, and Malcom, fresh from his history lesson, recalled the the fact that nearly a hundred years ago, a great Spanish fleet had been destroyed by the English under Admiral Nelson a little to the eastward on these very waters.

The next morning was a momentous one. In the early sunshine the ship entered the Bay of Gibraltar and anchored for several hours. Boats took the passengers to visit the town, and to Barbara and Bettina the supreme moment of travel in a foreign country had arrived; that in which they found another land and first touched it with their feet; and entering the streets found strange people and listened to a foreign tongue.

They drove through the queer, narrow, crooked streets, out upon the "neutral ground," and up to the gardens; bought an English newspaper; then, going back to the ship, looked up at the frowning rock threaded by those English galleries, which, upon occasion, can pour forth from their windows such a deadly hail.

Leaving the harbor, the ship passed slowly along between the "Pillars of Hercules," for so many centuries the western limit of the Old World, and entered the blue Mediterranean. And was this low dark line on the right really Africa, the Dark Continent, which until then had seemed only a dream—a far-away dream? What a sure reality it would ever be after this!

Mrs. Douglas had chosen happily when she decided to land at Genoa instead of at one of the northern ports; for aside from the fact that the whole Atlantic passage was calmer than it otherwise could have been, the beauty and interest of the days on the Mediterranean are almost without parallel in ocean travel.

The magnificent snow-capped mountains of the Spanish shore; the rugged northern coasts of the Balearic Islands; the knowledge that out just beyond sight lies Corsica, where was born the little island boy, so proud, ambitious, and unscrupulous as emperor, so sad and disappointed in his banishment and death; and then the long beautiful Riviera coast, which the steamships for Genoa really skirt, permitting their passengers to look into Nice, Bordighera, Monaco, San Remo, etc., and to realize all the picturesque beauty of their mountain background—all this gave three enchanting days to our little party before the ship sailed into the harbor of Genoa, La Superba, a well-merited title.

The city seemed now like a jewel in green setting, as its softly colored palaces, rising terrace above terrace, surrounded by rich tropical foliage, glowed in the rays of the setting sun.

Here Mrs. Douglas was to meet her brother; and she, Malcom, and Margery were full of eager excitement. It was hard to wait until the little crowd of people collected on the wharf should separate into distinct individuals.

"There he is! there is Uncle Robert! I see him!" cried Malcom. "He is waving his handkerchief from the top of his cane!"

While Mrs. Douglas and Margery pressed forward to send some token of recognition across the rapidly diminishing breadth of waters, Barbara and Bettina sought with vivid interest the figure and face of one whom they remembered but slightly, but of whom they had heard much. Robert Sumner was a name often mentioned in their home for, as a boy, and young man, he had been particularly dear to Dr. Burnett and had been held up as a model of all excellence before his own boys.

Some six years before the time of our story he was to marry a beautiful girl, who died almost on the eve of what was to have been their marriage-day. Stunned by the affliction, the young artist bade good-by to home and friends and went to Italy, feeling that he could bear his loss only under new conditions; and, ever since, that country had been his home. He had travelled widely, yet had always returned to Italy. "Next year I will go back to America," he had often thought; but there was still a shrinking from the coming into contact with painful associations. Only his sister and her children were left of the home circle and it were happier if they would come to him; so he had stayed on, a voluntary exile.

Not yet thirty years of age, he looked even younger as with shining eyes he watched the little group on the deck of the big approaching steamship. Of the strength of his affections no one could be doubtful who witnessed his warm, passionate embraces when, after long delay, the ship and shore were at last bound together.

"And can these be the little Barbara and Betty who used to sit on my knees?" he asked in wonder, as Mrs. Douglas drew forward the tall girls that they might share in his greeting.

"I thought I knew you, but am afraid we shall have to get acquainted all over again."

The following morning when, after breakfast, the young people had been put into a carriage for a drive all about the city, Mrs. Douglas had a long conversation with her brother. He told her of the pleasant home in Florence which he had prepared for her, and some of his plans for the coming months.

"But will not the care of so many young people be too much for you, my sister? Have you counted well the cost of added thought and care which our dear Doctor's daughters will impose? Tell me about them. Are they as sterling as their father and mother? I must believe they are neither giddy nor headstrong, else you would never have undertaken the care of them. Moreover, their faces contradict any such supposition. They are beautiful and very attractive; but are just at the age when every power is on the alert to have its fill of interest and enjoyment. Did you notice how their eyes sparkled as they took their seats in the carriage and looked out upon the strange, foreign sights?"

"Yes," answered Mrs. Douglas. "We must do all we can for them that this visit to the Old World shall be as truly a means of culture as their parents desire. You know I wrote you that it is difficult for the Doctor to afford it, but that he felt so earnestly the good that such an opportunity must bring his girls that he could not bear to refuse it. As for me, I love Barbara and Betty dearly and delight to care for them as for my own. Their influence is wholesome, and our little Margery loves them as if they were indeed sisters. I have thought much about what is best for all our young people to do during the coming months in Italy. Of course everything they see and hear will be an education, but I think we ought to have some definite plan for certainly a portion of their time. I have wished to talk to you about it.

"'Help my daughters to study,' said Dr. Burnett, and his feeling has given me new thoughts regarding my own children. Now there is one great field of study into which one can enter in this country as nowhere else—and this is art. Especially in Florence is the world of Italian painting opened before us—its beginnings and growth. Ought we not to put all of them, Barbara, Bettina, Malcom, and Margery into the most favorable conditions for entering upon the study of this great subject, which may prove a source of so much enjoyment and culture all their lives? I well remember my own wonder and pleasure when, years ago, our dear mother called my attention to it; and how much it has been to both you and me! You can help me here, Robert, for this is so much a part of your own life."

"I will think it all over, sister, and we will see what we can do. As for me, I am too happy just now in having you and the children with me to give thought to anything else. So talk to me to-day of nothing but your own dear selves."

Two days later our travellers were on their way down the western coast of Italy, threading tunnels, and snatching brief views of the Mediterranean on one side and smiling vineyards and quaint Italian cities on the other.

"We will not stop at Pisa," said Mr. Sumner, "but will come to visit it some time later from Florence; but you must watch for a fine view from the railway of its Cathedral, Leaning Tower, Baptistery, and Campo Santo. The mountains are withdrawing from us now, and I think we shall reach it soon."

"Oh! how like the pictures we have seen!" cried Malcom. "How fine! The tower does lean just as much as we have thought!"

"How beautiful it all is,—the blue hills, the green plain, and the soft yellow of the buildings!" said Bettina.

"Will you tell us something of it all, Mr. Sumner?" asked Barbara. "I know there is something wonderful and interesting, but cannot remember just what."

"There are many very interesting things about this old city," answered Mr. Sumner. "First of all, the striking changes through which it has passed. Once Pisa was on the sea, possessed a fine harbor, and in rich commerce was a rival of Genoa and Venice. She was a proud, eager, assertive city; of such worth that she was deemed a rich prize, and was captured by the Romans a few centuries B.C. Now the sea has left her and, with that, her commerce and importance in the world of trade. She is to-day so poor that there is nothing to tempt travellers to come to her save a magnificent climate and this wonderful group of buildings. The inhabitants are few and humble, her streets are grass-grown. Everything has stopped in poor old Pisa. Here Galileo was born, and lived for years; and in the Cathedral is a great swinging lamp which is said to have first suggested to his mind the motion of the pendulum, and from the top of the Leaning Tower he used to study the planets. The Tower is the Campanile, or Bell Tower, of the Cathedral. With regard to its position, there are different opinions. Some writers think it only an accident,—that the foundation of one side gave way during the building, thus producing the effect we see. Others think it was purposely so built, planned by some architect who desired to gain a unique effect and so prove his mastery over the subtleties of building. I confess that since I have seen the leaning towers of Bologna, which were erected about the same time, I am inclined to agree with the latter view."

"I should think, uncle," said Malcom, "that if such defective foundations had been laid, there would have been further trouble, and the poor Tower would have fallen long ago."

"Yes," replied Mr. Sumner, "it does not seem very reasonable to believe that they would have given way just enough to make the Tower lean as it does now, and that then it should remain stationary for so many centuries afterward. The Baptistery, or place for baptism, was formerly built in Italy separate from the Cathedral, as was the Campanile, just as we see them here. In northern countries and in more modern Italian cathedrals, we find all united in one building. The most interesting thing in this Baptistery is a magnificent marble pulpit covered with sculptures designed by Nicholas Pisano. To see it alone is worth a visit to Pisa. The long, low building that you saw beyond the other buildings is the Campo Santo, a name given to burial places in Italy, which, as you know, is a Latin term, and means 'holy ground.'"

"I think it is a beautiful name," said Bettina.

"Yes, there is a solemn rhythm about the words that pleases the ear rather more than does our word 'cemetery,'" said Mr. Sumner.

"But there is something especially interesting about this Campo Santo, isn't there?" queried Barbara, and added: "I do hope I shall remember all such things after I have really seen the places!"

"You surely will, my dear," said Mrs. Douglas; "ever afterward they will be realities to you, not mere stories."

Mr. Sumner resumed: "The Campo Santo of Pisa is the first one that was laid out in Italy, and it is still by far the most beautiful. It possesses the dimensions of Noah's Ark, and is literally holy ground, for it was filled with fifty-three shiploads of earth brought from Mount Calvary, so that the dead of Pisa repose in sacred ground. The inner sides of its walls were decorated with noble paintings, many of which are now completely faded. We will come to see those which remain some day."

"How strange it all is!" said Bettina. "How different from anything we see at home! Think of ships sent to the Holy Land for earth from Mount Calvary, and their coming back over the Mediterranean laden with such a cargo!"

"Only a superstitious, imaginative people, such as the Italians are, would have done such a thing," said Mrs. Douglas; "and only in the mediæval age of the world."

"But," she went on with a bright smile, "it is the same spirit that has reared such exquisite buildings for the worship of God and filled them with rare, sacred marbles and paintings that are beyond price to the world of art. I always feel when I come hither and see the present poverty of the beautiful land that the whole world is its debtor, and can never repay what it owes."

CHURCH OF THE ANNUNZIATA, FLORENCE.

CHURCH OF THE ANNUNZIATA, FLORENCE.

One afternoon, about two weeks later, Barbara and Bettina were sitting in their pleasant room in Florence. The wide-open windows looked out upon the slopes of that lovely hill on whose summit is perched Fiesole, the poor little old mother of Florence, who still holds watch over her beautiful daughter stretched at her feet. Scented airs which had swept all the way from distant blue hills over countless orange, olive, and mulberry groves filled the room, and fluttered the paper upon which the girls were writing; it was their weekly letter budget.

The fair faces were flushed as they bent over the crowded sheets so soon to be scanned by dear eyes at home. How much there was to tell of the events of the past week! Drives through the streets of the famous city; through the lovely Cascine; up to San Miniato and Fiesole; visits to churches, palaces, and picture-galleries; days filled to overflowing with the new life among foreign scenes.

Suddenly Barbara, throwing aside her pen, exclaimed:—

"Betty dear, don't you sometimes feel most horribly ignorant?"

"Why? when?"

"Oh! I am just writing about our visit to Santa Croce the other day. I enjoyed so much the fine spaces within the church, the softened light, and some of the monuments. But when we came to those chapels whose walls are covered with paintings,—you remember, where we met that Mr. Sherman and his daughters who came over on the Kaiser with us,—I tried to understand why they were so interested there. They were studying the paintings for such a long time, and I heard some of the things they were saying about them. They thought them perfectly wonderful; and that Miss Sherman who has such lovely eyes said she thought it worth coming from America to Italy just to see them and other works by the same artist. Mr. Sumner, too, heard what she said, and gave her such a pleased, admiring look. After they had gone out from the chapel where are pictures representing scenes in the life of St. Francis, I went in and looked and looked at them; but, try as hard as I could, I could not be one bit interested. The pictures are so queer, the figures so stiff, I could not see a beautiful or interesting thing about them. But I know I am all wrong. I do want to see what they saw, and to feel as they felt!"

"I liked the pictures because of their subject," said Bettina; "that dear St. Francis of Assisi who loved the birds and flowers, and talked to them as if they could understand him. But I did not see any beauty in them."

"We must learn what it is; we must do more than just look at all these early pictures that fill the churches and galleries just as we would look at wall paper, as so many people seemed to do in the Uffizi gallery the other day," said Barbara, emphatically. "This must be one of the things papa meant."

Just here came a knock on the door.

"May we come in, Margery and I?" asked Malcom. "Why! what is the matter? You look as if you had been talking of something unpleasant."

Bettina told of Barbara's trouble.

"How strange!" said Margery. "Mamma has just been talking to us about this very thing. She says that, if you like, Uncle Robert will teach us about the works of the Italian painters. You know he knows everything about them! He has even written a book about these paintings in Florence!"

"Yes," said Malcom with a comical shrug, "the idea is that we all spend one or two mornings every week studying stiff old Madonnas and Magdalenes and saints! I love noble and beautiful paintings as well as any one, but I wonder if I can ever learn anything that will make me care to look twice at some of those old things in the long entrance gallery of the Uffizi. I doubt it. Give me the old palaces where the Medici lived, and let me study up what they did. Or even Dante, or Michael Angelo! He was an artist who is worth studying about. Why! do you know, he built the fortifications of San Miniato and—"

"But," interrupted Barbara, "you know that whenever Italy is written or talked about, her art seems to be the very most important thing. I was reading only the other day an article in which the writer said that undoubtedly the chief mission or gift of Italy to the world is her paintings,—her old paintings,—and that this mission is all fulfilled. Now, if this be true, do we wish to come here and go away without learning all that we possibly can of them? I think that would be foolish."

"And," added Bettina, "I think one of the most interesting studies in the world is about these same old saints whom you dislike so much, Malcom. They were heroes; and I think some of them were a great deal grander than those mythological characters you so dote upon. If your uncle will only be so good as to talk to us of the pictures! Let us go at once and thank him. Now, Malcom, you will be enthusiastic about it, will you not? There will be so much time for all the other things."

Bettina put her arm affectionately about Margery, and smiled into Malcom's face, as they all went to seek Mrs. Douglas and Mr. Sumner.

"Here come the victims, Uncle Rob! three willing ones,—Barbara, who is ever sighing for new worlds to conquer; Betty, who already dotes upon St. Sebastian stuck full of arrows and St. Lucia carrying her eyes on a platter; Madge, who would go to the rack if only you led the way,—and poor rebellious, inartistic I."

"But, my boy—" began Mrs. Douglas.

"Oh! I will do it all if only the girls will climb the Campanile and Galileo's Tower with me and it does not interfere with our drives and walks. If this is to become an æsthetic crowd, I don't wish to be left out," laughed Malcom.

A morning was decided upon for the first lesson.

"We will begin at the beginning," said Mr. Sumner; "one vital mistake often made is in not starting far enough back. In order to realize in the slightest degree the true work of these old masters, one must know in what condition the art was before their time; or rather, that there was no art. So we will first go to the Accademia delle Belle Arti, or Academy, as we will call it, and from there to the church, Santa Maria Novella. And one thing more,—you are welcome to go to my library and learn all you can from the books there. I am sure I do not need to tell those who have studied so much as you already have that the knowledge you shall gain from coming into contact with any new thing must be in a great degree measured by that which you take to it."

"How good you are to give us so much of your time, Mr. Sumner," said Barbara, with sparkling eyes. "How can we ever repay you?"

"By learning to love this subject somewhat as I love it," replied Mr. Sumner; but he thought as he felt the magnetism of her young enthusiasm that he might gain something of compensation which it was impossible to put into words.

"Are you not going with us, dear Mrs. Douglas?" asked Bettina, as the little party were preparing to set forth on the appointed morning.

"Not to-day, dear, for I have another engagement"

"I think I know what mamma is going to do," said Margery as they left the house. "I heard the housemaid, Anita, telling her last evening about the illness of her little brother, and saying that her mother is so poor that she cannot get for the child what he needs. I think mamma is going to see them this morning."

"Just like that blessed mother of ours!" exclaimed Malcom. "There is never anybody in want near her about whom she is not sure to find out and to help! It will be just the same here as at home; Italians or Americans—all are alike to her. She will give up anything for herself in order to do for them."

"I am glad you know her so well," said his uncle, with a smile. "There is no danger that you can ever admire your mother too much."

"Oh!" exclaimed Barbara, as after a little walk they entered a square surrounded by massive buildings, with arcades, all white with the sunshine. "Look at that building! It is decorated with those dear little babies, all swathed, whose photographs we have so often seen in the Boston art stores. What is it? Where are we?"

"In the Piazza dell' Annunziata," replied Mr. Sumner, "and an interesting place it is. That building is the Foundling Hospital, a very ancient and famous institution. And the 'swathed babies' are the work of Andrea della Robbia."

"Poor little innocents! How tired they must be, wrapped up like mummies and stuck on the wall like specimen butterflies!" whispered Malcom in an aside to Bettina.

"Hush! hush!" laughed she. "Your uncle will hear you."

"This beautiful church just here on our right," continued Mr. Sumner, "is the church of the S.S. Annunziata or the most Holy Annunciation. It was founded in the middle of the thirteenth century by seven noble Florentines, who used to meet daily to sing Ave Maria in a chapel situated where the Campanile of the Cathedral now stands. It has been somewhat modernized and is now the most fashionable church in Florence. It contains some very interesting paintings, which we will visit by and by."

"Every step we take in this beautiful city is full of interest, and how different from anything we can find at home!" exclaimed Bettina. "Look at the color of these buildings, and their exquisite arches! See the soft painting over the door of the church, and the sculptured bits everywhere! I begin, just a little, to see why Florence is called the art city."

"But only a little, yet," said Mr. Sumner, with a pleased look. "You are just on the threshold of the knowledge of this fair city. Not what she outwardly is, but what she contains, and what her children have wrought, constitute her wealth of art. Do you remember, Margery, what name the poet Shelley gives Florence in that beautiful poem you were reading yesterday?"

dreamily recited Margery, her sweet face flushing as all eyes looked at her.

"Yes," smiled her uncle. "Florence, as foster-nurse, has cherished for the world the art-treasures of early centuries in Italy, so that there is no other city on earth in which we can learn so much of the 'revival of art,' as it is called, which took place after the barrenness of the Dark Ages, as in this. But here we are at the Academy. I shall not allow you to look at much here this morning. We will go and sit in the farther corner of this first corridor, for I wish to talk a little, and just here we shall find all that I need for illustration."

"You need not put on such a martyr-look, Malcom," continued he, as they walked on. "I prophesy that not one here present will feel more solid interest in the work we are beginning than you will, my boy."

When Mr. Sumner had gathered the little group about him, he began to talk of the beauties of Greek art—how it had flourished for centuries before Christ.

"But I thought Greek art consisted of sculptures," said Barbara.

"Much of it was sculptured,—all of it which remains,—but we have evidence that the Greeks also produced beautiful paintings, which, could they have been preserved, might be not unworthy rivals of modern masterpieces," replied Mr. Sumner. "After the Roman invasion of Greece, these ancient works of art were mostly destroyed. Rome possessed no fine art of her own, but imported Greek artists to produce for her. These, taken away from their native land, and having no noble works around them for inspiration, began simply to copy each other, and so the art degenerated from century to century. The growing Christian religion, which forbade the picturing of any living beauty, gave the death-blow to such excellence as remained. A style of painting followed which received the name of Greek Byzantine. In it was no study of life; all was most strikingly conventional, and it grew steadily worse and worse. A comparison of the paintings and mosaics of the sixth, seventh, eighth, and ninth centuries shows the rapid decline of all art qualities. Finally every figure produced was a most arrant libel on nature. It was always painted against a flat gold background; the limbs were wholly devoid of action; the feet and hands hung helplessly; and the eyes were round and staring. The flesh tints were a dull brick red, and all else a dreary brown."

"Come here," said he, rising, "and see an example of this Greek Byzantine art,—this Magdalen. Study it well."

"Oh, oh, how dreadful!" chorussed the voices of all.

"Uncle Rob, do you mean to say there was no painting in the world better than this in the ninth—or thereabouts—century?" asked Malcom, with wondering eyes.

"I mean to say just that, Malcom. But I must tell you something more about this same Greek Byzantine painting, for there is a school of it to-day. Should you go to Southern Italy or to Russia, you would find many booths for trading, in the back of which you would see a Madonna, or some saint, painted in just this style. These pictures have gained a superstitious value among the lower classes of the people, and are believed to possess a miraculous power. In Mt. Athos, Greece, is a school that still produces them. Doubtless this has grown out of the fact that several of these old paintings, notably Madonnas, are treasured in the churches, and the people are taught that miracles have been wrought by them. In the Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome, is an example (the people are told that it was painted by St. Luke), and during the plague in Rome, and also during a great fire which was most disastrous, this painting was borne through the city by priests in holy procession, and the tradition is that both plague and fire were stayed."

"What a painfully ridiculous figure!" exclaimed Barbara, who had been silently absorbed in study. "It is painful because every line looks as if the artist had done his very best, and that is so utterly bad. It means absolutely nothing."

"You have fathomed the woful secret," replied Mr. Sumner. "It shows no evidence of the slightest thought. Only a man's fingers produced this. All power of originality had become lost; all desire for it was unknown."

"Then, how did things ever get better?" asked Malcom.

"An interesting question. I wish you all would read some before I tell you any more. Find something, please, that treats of the beginnings of Christian art in the Catacombs of Rome. Read about the manuscript illuminations produced by monks of the tenth and eleventh centuries, which are to be found in some great libraries. In these we find the best art of that time,"

ACADEMY, FLORENCE.

BYZANTINE MAGDALEN.

ACADEMY, FLORENCE.

BYZANTINE MAGDALEN.

"If you find anything about Cimabue and Giotto," he added, "you would better read that also, for the work of these old painters will be the subject of our next lesson. For it, we will go to the church Santa Maria Novella."

"And Santa Croce?" asked Barbara, more timidly than was her wont.

"And Santa Croce too," smilingly added Mr. Sumner.

"And now, Malcom, if you can find a wide carriage, we all will drive for an hour before going home."

DUOMO AND CAMPANILE. FLORENCE.

DUOMO AND CAMPANILE. FLORENCE.

One day Malcom met an old fellow-student. Coming home, he told his mother of him, and asked permission to bring him for introduction.

"His name is Howard Sinclair. I did not know him very well in the school, for he was some way ahead of me. He is now in Harvard College. But his lungs are very weak; and last winter the doctors sent him to Egypt, and told him he must stay for at least two years in the warmer countries. He is lonely and pretty blue, I judge; was glad enough to see me."

"Poor boy! Yes, bring him here, and I will talk with him. Perhaps we can make it more pleasant for him. You are sure his character is beyond question, Malcom?"

"I think so. He has lots of money, and is inclined to spend it freely, but I know he was called a pretty fine fellow in the school, though not very well known by many. He is rather 'toney,' you know,—held his head too high for common fellows. The teachers especially liked him; for he is awfully bright, and took honors right along."

The next day Malcom brought his friend to his mother, whose heart he won at once by his evident delicate health, his gentlemanly manners, and, perhaps most of all, because he had been an orphan for years, and was so much alone in the world. She decided to welcome him to her home, and to give him the companionship of her young people.

Howard Sinclair was a young man of brilliant intellectual promise. He had inherited most keen sensibilities, an almost morbid delicacy of thought, a variable disposition, and a frail body. Both father and mother died before he was ten years of age, leaving a large fortune for him, their only child; and, since then, his home had been with an aged grandmother. Without any young companions in the home, and lacking desire for activity, he had given himself up to an almost wholly sedentary life. The body, so delicate by nature, had always been made secondary to the alert mind. His luxurious tastes could all be gratified, and thus far he had lived like some conservatory plant.

The very darling of his grandmother's heart, it was like death to her to part from him when the physicians decided that to save his life it was an imperative necessity that he should live for a a time in a warmer climate. It was an utter impossibility for her to accompany him. He shrank from any other companion, therefore had set forth with only his faithful John, who had been an old servant in the family before he was born, as valet. He went first to Egypt, where he had remained as long as the heat would permit, then had gone northwest to the Italian lakes and Switzerland, whence he had now come to spend a time in Florence.

Lonely, homesick, and disheartened, it was indeed like a "gift of the gods" to him when one day, as he was leaving his banker's on Via Tornabuoni he met the familiar face of Malcom Douglas. And when he was welcomed to his old schoolmate's home and family circle, the weary young man felt for the first time in many months the sensation of rest and peace.

His evident lack of physical strength, and the quickly coming and going color in his cheeks, told Mrs. Douglas that he could never know perfect health; but he said that the change of country and climate had already done him much good, and this encouraged him to think of staying from home a year or two in the hope that then all danger of active disease might have passed.

He so evidently longed for companionship that Malcom and the girls told him of their life,—of their Italian lessons,—their reading,—Mr. Sumner's talks about Italian painting,—Malcom's private college studies (which he had promised his mother to pursue if she would give him this year abroad), and all that which was filling their days. He was especially interested in their lessons on the Italian masters of painting, and asked if they would permit him to join them.

"If you will only come to me when you have any trouble with your Greek and Latin, Malcom," he said, "perhaps I can repay you in the slightest degree for the wonderful pleasure this would give me."

So as Mr. Sumner was willing, his little class received the addition of Howard Sinclair.

"Why so sober, Malcom?" asked his mother, as she found him alone by himself. "Is not the arrangement that your friend join you agreeable?"

"Oh, yes, mother, he is a nice fellow, though a sort of a prig, and I wish to do all we can for him; only—I do hope he will not monopolize Betty and Barbara always, as he has seemed to do this afternoon."

"My boy, beware of that little green imp we read of," laughed Mrs. Douglas. "You have been too thoroughly 'monarch of all' thus far. Can you not share your realm with this homesick young man?"

"But he has always had all for himself, mother. He does not know what it is to share."

"Malcom! be yourself."

The mother's eyes looked straight up into those of her tall boy, and her hand sought his with a firm, warm pressure that made him fling back his noble young head with an emphatic "I am ashamed of myself! Thank you, mother dear."

That evening, as all were sitting on the balcony watching the soft, rosy afterglow that was creeping over the hills and turning to glowing points the domes and spires of the fair city, Mr. Sumner said:—

"If you are willing, I would like to talk with you a little before we make our visits to Santa Maria Novella and Santa Croce to-morrow. You will understand better the old pictures we shall see there if we consider beforehand what we ought to look for in any picture or other work of art. Too many go to them as to some sort of recreation,—simply for amusement,—simply to gratify their love for beautiful color and form, and so, to these, the most beautiful picture is always the best. But this is a low estimate of the great art of painting, for it is simply one of man's means of expression, just as music or poetry is. The artist learns to compose his pictures, to draw his forms, to lay on his colors, just as the poet learns the meanings of words, rhetorical figures, and the laws of harmony and rhythm, or the musician his notes and scales and harmonies of sound."

"I see this is a new thought to you," continued he, after a moment spent in studying the faces about him. "Let us follow it. What is the use of this preparation of study in art, poetry, or music? Is it solely for the perfection of itself? We often hear nowadays the expression, 'art for art's sake,' and by some it is accounted a grand thought and a noble rallying-cry for artists. And so it truly is if the very broadest and highest possible meaning is given to the word 'art.' If it means the embodying of some noble, beautiful, soul-moving thought in a form that can be seen and understood, and means nothing less than this, then it is indeed a worthy motto. But to too many, I fear, it means only the painting of beauty for beauty's sake. That is, the thought embodied, the message to some soul, which every picture ought to contain, and which every noble picture that is worthy to live must contain, becomes of little or no value compared with the play of color and light and form.

"Let me explain further," he went on, even more earnestly. "Imagine that we are looking at a picture, and we admire exceedingly the perfection of drawing its author has displayed,—the wonderful breadth of composition,—the harmony of color-masses. The moment is full of keen enjoyment for us; but the vital thing, after all, is, what impression shall we take away with us. Has the picture borne us any message? Has it been either an interpretation or a revelation of something? Shall we remember it?"

"But is not simple beauty sometimes a revelation, Mr. Sumner?" asked Barbara,—"as in a landscape, or seascape, or the painting of a child's face?"

"Certainly, if the artist has shown by his work that this beauty has stirred depths of feeling in himself, and his effort has been to reveal what he has felt to others. If you seek to find this in pictures you will soon learn to distinguish between those (too many of which are painted to-day) whose only excellence lies in trick of handling or cunning disposition of color-masses,—because these things are all of which the artist has thought,—and those that have grown out of the highest art-desire, which is to bear some message of the restfulness, the power, the beauty, or the innocence of nature to the hearts of other men.

"And there is one thing more that we must not forget. There may be pictures with bad motifs as well as good ones—weak and simple ones, as well as strong and holy ones—and yet they may be full of all artistic qualities of representation. What is true with regard to literature is true in respect to art. It is, after all, the message that determines the degree of nobility.

wrote Mr. Browning, and we should always endeavor to find out whether the artist has loaned his mind or merely his fingers and his knowledge of the use of his materials. If we find thought in his picture, we should then ask to what service he has put it.

"If a poem consist only of words and rhythms, how long do you think it ought to live? And if a picture possess merely forms and colors, however beautiful they may be, it deserves no more fame. And how much worse if there be meaning, and it be base and unworthy!"

"Does he not put it well?" whispered Malcom to Bettina from his usual seat between her and Margery. "I feel as if he were pouring new thoughts into me."

"Now, the one thing I desire to impress upon you to-night," continued Mr. Sumner, "is that these old masters of painting who lived in the thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth centuries had messages to give their fellow-men. Their great endeavor was to interpret God's word to them,—you know that in those days and in this land there was no Bible open to the common people,—and what we must chiefly look for in their pictures is to see whether or not they told the message as well as the limitation of their art-language permitted.

"At first, no laws of perspective were known. None knew how to draw anything correctly. No color-harmonies had been thought of. These men must needs stammer when they tried to express themselves; but as much greater as thought is than the mere expression of it so much greater are many of their works, in the true sense, than the mass of pictures that make up our exhibitions of the present day.

"Then, also, it is a source of the deepest interest to one who loves this art to watch its growth in means of expression—its steady development—until, finally, we find the noblest thoughts expressed in perfect forms and coloring. This we can do here in Florence as nowhere else, for the Florentine school of painting was the first of importance in Italy.

"So," he concluded, "do not look for beauty in these pictures which we are first to study; instead of it, you will find much ugliness. But strive to put yourselves into the place of the old artists, to feel as they felt. See what impelled them to paint. Recognize the feebleness of their means of expression. Watch for indications in history of the effect of their pictures upon the people. Strive to find originality in them, if it be there, for this quality gives a man's work a certain positive greatness wherever we find it; and so learn to become worthy judges of that which you study. Soon, like me, you will look with pity on those who can see nothing worthy of a second glance in these treasures of the past.

"There! I have preached you a sermon, I am afraid. Are you tired?" and his bright glance searched the faces about him.

Their expression would have been satisfactory without the eager protestations that answered his question.

When, a little later, Barbara and Bettina, each seated before her dainty toilet-table, were brushing their hair, they, as usual, chatted about the events of the day. Never had there been so much to talk over and so little time to do it in as during these crowded weeks, when pleasure and study were hand in hand. For though they read and studied, yet there were drives, and receptions in artists' studios, and, because of Robert Sumner's long residence in Florence, they had even begun to receive invitations to small and select parties, where they met charming people.

This very morning they had driven with Mrs. Douglas through some of the oldest parts of Florence. They were reading together George Eliot's "Romola," and were connecting all its events with this city in which the scenes are laid. Read in this way, it seemed like a new book to them, and possessed an air of reality that awakened their enthusiasm as nothing else could have done. And then in the afternoon had been the meeting with the new friend; tea in the little garden behind the house; and the evening on the balcony.

Naturally their conversation soon turned to Howard Sinclair.

"What a strange life for one so young!" said Bettina. "Malcom says there is no limit to his wealth. He lives in the winter in one of those grandest houses on Commonwealth Avenue in Boston, and has summer houses in two or three places. And yet how poor in many ways!" she continued after a little pause—"so much poorer than we! No father and mother,—no brothers and sisters,—and forced to leave his home because he is so ill! Poor fellow! How do you like him, Bab? He seemed to admire you sufficiently, for he hardly took his eyes from you."

"Like him?" slowly returned Barbara. "To tell the truth, Betty, I hardly know. Somehow I feel strangely about him. I like him well enough so far, but I believe I am a bit afraid, and whether it is of him or not, I cannot tell. Somehow I feel as if things are going to be different from what they have been, and—I don't know—I believe I almost wish Malcom had not known him."

"Why, Bab dear! what do you mean? Don't be nervous; that is not like you. Nothing could happen to make us unhappy while we are with these dear people,—nothing, that is, if our dear ones at home are well. I wish he had not stared at you so much with those great eyes, if it makes you feel uncomfortable, but how he could have helped admiring you, sister mine, is more than I know,—for you were lovely beyond everything this afternoon;" and Betty impulsively sprang up to give her sister a hug and a kiss.

"To change the subject," she added, "how did you like Mr. Sumner's talk this evening?"

"Oh! more than words can tell! Betty, I believe, next to our own dear papa, he is the grandest man alive. I always feel when he talks as if nothing were too difficult to attempt; as if nothing were too beautiful to believe. And he is so young too, in feeling; so wise and yet so full of sympathy with all our young nonsense. He is simply perfect." And she drew a long breath.

"I think so too; and he practises what he preaches in his own painting. For don't you remember those pictures we saw in his studio the other day? How he has painted those Egyptian scenes! A perfect tremor ran over me as I felt the terrible, solemn loneliness of that one camel and his rider in the limitless stretch of desert. I felt quite as he must have felt, I am sure; and the desert will always seem a different thing to me because I looked at that picture. And then that sweet, strong, overcoming woman's face! How much she had lived through! What a lesson of triumph over all weakness and sorrow it teaches! I am so thankful every minute that dear Mrs. Douglas asked us to come with her, that our darling papa and mamma allowed us to come, and that everything is so pleasant in this dear, delightful Florence."

And Bettina fell asleep almost the minute her head rested on her pillow, with a happy smile curving her beautiful lips.

But Barbara tossed long on the little white bed in the opposite corner of the room. It was difficult to go to sleep, so many thoughts crowded upon her. Finally she resolutely set herself to recall Mr. Sumner's words of the evening. Then, as she remembered the little lingering of his eyes upon her own as he bade his group of listeners good night, the glad thought came, "He knows I am trying to learn, and that I appreciate all he is doing for me," and so her last thought was not for the new friend the day had brought, but for Robert Sumner.

SANTA MARIA NOVELLA, FLORENCE.

SANTA MARIA NOVELLA, FLORENCE.

It was a charming morning in early November when Mr. Sumner and his little company of students of Florentine art gathered before the broad steps which lead up to the entrance of Santa Maria Novella. The Italian sky, less soft than in midsummer, gleamed brightly blue. The square tower of the old Fiesole Cathedral had been sharply defined as they turned to look at it when leaving their home; and Giotto's Campanile, of which they had caught a glimpse on their way hither, shone like a white lily in the morning sunlight. The sweet, invigorating air, the bustle of the busy streets, the happiness of youth and pleasant expectancy caused all hearts to beat high, and it was a group of eager faces that turned toward the grand old church whose marble sides show the discoloration of centuries.

At Mr. Sumner's invitation all sat on the steps in a sunny corner while he talked of Cimabue,—the first great name in the history of Italian painting,—the man who was great enough to dare attempt to change conditions that existed in his time, which was the latter part of the thirteenth century. He told them how, though a nobleman possessing wealth and honor, he had loved painting and had given his life to it; and how, having been a man arrogant of all criticism, he was fitted to be a pioneer; to break from old traditions, and to infuse life into the dead Byzantine art.

He told them how the people, ever quick to feel any change, were delighted to recognize, in a picture, life, movement, and expression, however slight. How, one day six hundred years ago, a gay procession, with banners and songs, bore a large painting, the Madonna and Child, from the artist's studio, quite a distance away, through the streets and up to the steps on which they were sitting; and how priests chanting hymns and bearing church banners came out to receive the picture.

"And through all these centuries it has here remained," he continued. "It is, of course, scarred by time and dark with the smoke of incense. When you look upon it I wish you would remember what I told you the other evening about that for which we should look in a picture. Be sympathetic. Put yourself in old Cimabue's place and in that of the people who had known only such figures in painting as the Magdalen you saw last week in the Academy. Then, though these figures are so stiff and almost lifeless, though the picture is Byzantine in character, you will see beyond all this a faint expression in the Madonna's face, a little life and action in the Christ-child, who holds up his tiny hand in blessing.

"If you do not look for this you may miss it,—miss all that which gives worth to Cimabue and his art. As thoughtful a mind as that of our own Hawthorne saw only the false in it, and missed the attempt for truth; and so said he only wished 'another procession would come and take the picture from the church, and reverently burn it.' Ah, Malcom, I see your eyes found that in your reading, and you thought in what good company you might be."

"What kind of painting is it?" queried Barbara, as a few minutes later they stood in the little chapel, and looked up at Cimabue's quaint Madonna and Child.

"It is called tempera, and is laid upon wood. In this process the paints are mixed with some glutinous substance, such as the albumen of eggs, glue, etc., which causes them to adhere to the surface on which they are placed."

"What do you think was the cause of Cimabue's taking such an advance step, Mr. Sumner?" asked Howard Sinclair, after a pause, during which all studied the picture.

"It must have been a something caught from the spirit of the time. A stir, an awakening, was taking place in Italy. Dante and Petrarch were in a few years to think and write. The time had come for a new art."

"I do see the difference between this and those Academy pictures," said Bettina, "even though it is so queer, and painted in such colors."

"And I," "And I," quickly added Barbara and Margery.

"I think those angels' faces are interesting," continued Barbara. "They are not all just alike, but look as if each had some thought of his own. They seem proud of their burden as they hold up the Madonna and Child."

"Oh, nonsense, Barbara! you are putting too much imagination in there," exclaimed Malcom. "I think old Cimabue did do something, but it is an awfully bad picture, after all. There is one thing, though; it is not so flat as that Academy Magdalen. The child's head seems round, and I do think his face has a bit of expression."

So they looked and chatted on, and took little note of coming and going tourists, who glanced with curiosity from them to the old dark picture above, and then back to the fresh, eager, beautiful faces,—the greater part ever finding in the latter the keener attraction.

"I always have one thought when I look at this," finally said Mr. Sumner, "that perhaps will be interesting to you, and linger in your minds. This Madonna and Child seems to form a link and also to mark a division between all those which went before it in Christian art and all those that have followed. It is the last Byzantine Madonna and is the first of the long, noble list which has come from the hands of artists who have lived since the thirteenth century.

"We will not stay here longer now, for I know you will come again more than once to study it. There is much valuable historic art in this church which you will understand better when you have learned more. Yonder in the Strozzi Chapel is some of the very best work of an old painter called Orcagna, while here in the choir are notable frescoes by Ghirlandajo; but now I shall take you down these steps between the two into the cloister and there we will talk of Giotto. I know how busy you have been reading about this wonderful old master, for I could not help hearing snatches of your talk about him all through the past week. His figure looms up most important of all among the early painters of Florence. You know how Cimabue, clad in his scarlet robe and hood, insignia of nobility, riding out one day to a little town lying on one of yonder blue hills, found a little, dark-faced shepherd-boy watching his father's sheep, and amusing himself by drawing a picture of one, with only a sharp stone for a pencil. Interested in the boy, he took pains to visit his father and gain his permission to take him as a pupil to Florence. So Giotto came to begin his art-life. What are you thinking of, little Margery?"

"Only a bit of Dante's writing which I read with mother the other day," said she, blushing. "I was thinking how little Cimabue then thought that this poor, ignorant shepherd-boy would ever cause these lines to be written:—

"Yes, indeed! Giotto did eclipse his master's fame, for he went so much farther,—but only in the same path, however; so we must not take from Cimabue any of the honor that is due him. But for Giotto the old Byzantine method of painting on all gold backgrounds was abolished. This boy, though born of peasants, was not only gifted with keen powers of observation of nature and mankind and a devotion to the representation of things truly as they are, but, beyond and above all this, with one other quality that made his work of incalculable worth to the people among whom he painted. This was a delicate appreciation of the true relations between earthly and spiritual things.

"Before him, as we have seen, all art was most unnatural and monastic,—utterly destitute of sympathy with the feelings of the common people. Giotto changed all this. He made the Christ-child a loving baby; the Madonna a loving mother into whose joy and suffering all mothers' hearts could enter; angels were servants of men; miracles were wrought by God because He loved and desired to help men; the pictured men and women were like themselves because they smiled and grieved and acted even as they did. All this change Giotto made in the spirit of pictures; and in the ways of painting he also wrought a complete revolution. 'There are no such things as gold backgrounds in nature,' he said; 'I will have my people out of doors or in their homes.' And so he painted the blue sky and rocks and trees and grass, and dressed his men and women in pure, fresh colors, and represented them as if engaged in home duties in the house or in the field. He introduced many characters into his story pictures,—angel visitants, neighbors, wandering shepherds, and even domestic animals. He brought the art of painting down into the minds and hearts of all who looked upon them."

"I never have realized until lately," said Barbara, "how painting can be made a source of education and pleasure to everybody. It is so different here from what it is at home, especially because the churches are full of pictures. There we go into the art museums or the galleries of different art-clubs,—the only places where pictures are to be found,—and meet only those people that can afford luxuries; and so the art itself seems a luxury. But here I have seen such poor, sad-looking people, who seem to forget all their miseries in looking at some beautiful sacred picture. Only the other day I overheard a poor woman, whose clothes were wretched and who had one child in her arms and another beside her, trying to explain a picture to them, and she lingered and lingered before it, and then turned away with a pleased, restful face."

"Yes, it is the spirit of pictures and their truth to nature that appeal to the mass of people here," replied Mr. Sumner, "and so it must be everywhere. I have been very glad to read in my papers from home that free art exhibitions have been occasionally opened in the poor quarters of our cities. Should the movement become general, as I hope it will, it must work good in more than one direction. Not only could those who have hitherto been shut out from this means of pleasure and education receive and profit by it, but the art itself would gain a wholesome impulse. A new class of critics would be heard—those unversed in art-parlance—who would not talk of line, tone, color-harmonies and technique, but would go to the very heart of picture and painter; and I think the truest artists would listen to them and so gain something.