The Project Gutenberg EBook of An Apology For The Study of Northern Antiquities, by Elizabeth Elstob This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: An Apology For The Study of Northern Antiquities Author: Elizabeth Elstob Commentator: Charles Peake Release Date: March 11, 2005 [EBook #15329] Posting Date: July 19, 2009 Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK NORTHERN ANTIQUITIES *** Produced by David Starner, Louise Hope and the Online Distributed

This text uses UTF-8 (Unicode) file encoding. If the apostrophes and quotation marks in this paragraph appear as garbage, you may have an incompatible browser or unavailable fonts. First, make sure that your browser’s “character set” or “file encoding” is set to Unicode (UTF-8). You may also need to change the default font.

The primary text includes a number of brief citations from languages other than English, and in scripts other than Roman. Text printed in blackletter type—German, Middle English, Old French—is shown like this (boldface, sans-serif). All passages in non-Roman scripts include mouse-hover transliterations. Note that font support for Gothic and Saxon is limited, so your browser may not be able to display these texts as printed.

Changes or corrections to the text are shown with mouse-hover popups.

Richard C. Boys, University of

Michigan

Ralph Cohen, University of

California, Los Angeles

Vinton A. Dearing, University of

California, Los Angeles

Lawrence Clark Powell, Clark

Memorial Library

W. Earl Britton, University of Michigan

Emmett L. Avery, State College of

Washington

Benjamin Boyce, Duke

University

Louis Bredvold, University of

Michigan

John Butt, King’s College,

University of Durham

James L. Clifford, Columbia

University

Arthur Friedman, University of

Chicago

Edward Niles Hooker, University of

California, Los Angeles

Louis A. Landa, Princeton

University

Samuel H. Monk, University of

Minnesota

Ernest C. Mossner, University of

Texas

James Sutherland, University

College, London

H. T. Swedenberg, Jr.,

University of California, Los Angeles

Edna C. Davis, Clark Memorial Library

The answerers who rushed into print in 1712 against Swift’s Proposal for Correcting, Improving and Ascertaining the English Tongue were so obviously moved by the spirit of faction that, apart from a few debating points and minor corrections, it is difficult to disentangle their legitimate criticisms from their political prejudices. As Professor Landa has written in his introduction to Oldmiron’s Reflections on Dr. Swift’s Letter to Harley and Mainwaring’s The British Academy (Augustan Reprint Society, 1948): “It is not as literature that these two answers to Swift are to be judged. They are minor, though interesting, documents in political warfare which cut athwart a significant cultural controversy.”

Elizabeth Elstob’s Apology for the Study of Northern Antiquities prefixed to her Rudiments of Grammar for the English-Saxon Tongue is an answer of a very different kind. It did not appear until 1715; it exhibits no political bias; it agrees with Swift’s denunciation of certain current linguistic habits; and it does not reject the very idea of regulating the language as repugnant to the sturdy independence of the Briton. Elizabeth Elstob speaks not for a party but for the group of antiquarian scholars, led by Dr. Hickes, who were developing and popularizing the study of the Anglo-Saxon origins of the English language--a study which had really started in the seventeenth century.

What irritated Miss Elstob in the Proposal was not Swift’s eulogy or Harley and the Tory ministry, but his scornful reference to antiquarians as “laborious ii men of low genius,” his failure to recognize that his manifest ignorance of the origins of the language was any bar to his pronouncing on it or legislating for it, and his repetition of some of the traditional criticisms of the Teutonic elements in the language, in particular the monosyllables and consonants. Her sense of injury was personal as well as academic. Her brother William and her revered master Dr. Hickes were among the antiquarians whom Swift had casually insulted, and she herself had published an elaborate edition of An English-Saxon Homily on the Birthday of St. Gregory (1709) and was at work on an Anglo-Saxon homilarium. Moreover she had a particular affection for her field of study, because it had enabled her to surmount the obstacles to learning which had been put in her path as a girl, and which had prevented her, then, from acquiring a classical education. Her Rudiments, the first Anglo-Saxon grammar written in English, was specifically designed to encourage ladies suffering from similar educational disabilities to find an intellectual pursuit. Her personal indignation is shown in her sharp answer to Swift’s insulting phrase, and in her retaliatory classification of the Dean among the “light and fluttering wits.”

As a linguistic historian she has no difficulty in exposing Swift’s ignorance, and in establishing her claim that if there is any refining or ascertaining of the English language to be done, the antiquarian scholars must be consulted. But it is when she writes as a literary critic, defending the English language, with its monosyllables and consonants, as a literary medium, that she is most interesting.

There was nothing new in what Swift had said of the character of the English language; he was merely echoing criticisms which had been expressed frequently since the early sixteenth century. The number of English monosyllables was sometimes complained of, because to ears trained on the classical languages they sounded harsh, barking, unfitted for eloquence; sometimes because they were believed to impede the metrical flow in poetry; sometimes because, being particularly iii characteristic of colloquial speech, they were considered low; and often because they were associated with the languages of the Teutonic tribes which had escaped the full refining influence of Roman civilization. Swift followed writers like Nash and Dekker in emphasizing the first and last of these objections.

There were, of course, stock answers to these stock objections. Such criticism of one’s mother tongue was said to be unpatriotic or positively disloyal. If it was difficult to maintain that English was as smooth and euphonious as Italian, it could be maintained that its monosyllables and consonants gave it a characteristic and masculine brevity and force. Monosyllables were also very convenient for the formation of compound words, and, it was argued, should, when properly managed, be an asset rather than a handicap to the English rhymester. By the time Swift and Miss Elstob were writing, an increasing number of antiquarian Germanophils (and also pro-Hanoverians) were prepared to claim Teutonic descent with pride.

Most of these arguments had been bandied backwards and forwards rather inconclusively since the sixteenth century, and Addison in The Spectator No. 135 expresses a typically moderate opinion on the matter: the English language, he says, abounds in monosyllables,

which gives us an opportunity of delivering our thoughts in few sounds. This indeed takes off from the elegance of our tongue, but at the same time expresses our ideas in the readiest manner, and consequently answers the first design of speech better than the multitude of syllables, which make the words of other languages more tunable and sonorous.

It is likely that neither Swift nor Miss Elstob would have found much to disagree with in that sentence. Swift certainly never proposed any reduction in the number of English monosyllables, and the simplicity of style which he described as “one of the greatest perfections in any language,” which seemed to him best exemplified in the English Bible, and which he himself practised so iv brilliantly, has in English a very marked monosyllabic character.

But in his enthusiasm to stamp out the practice of abbreviating, beheading and curtailing polysyllables--a practice which seemed to him a threat to both the elegance and permanence of the language--he described it as part of a tendency of the English to relapse into their Northern barbarity by multiplying monosyllables and eliding vowels between the rough and frequent consonants of their language. His ignorance of the historical origins of the language and his rather hackneyed remarks on its character do not invalidate the general scheme of his Proposal or his particular criticisms of current linguistic habits, but they did lay him open to the very penetrating and decisive attack of Elizabeth Elstob.

In her reply to Swift she repeats all the stock defenses of the English monosyllables and consonants, but, by presenting them in combination, and in a manner at once scholarly and forceful, she makes the most convincing case against Swift. Unlike most of her predecessors, Miss Elstob is not on the defensive. She is always ready to give a sharp personal turn to her scholarly refutations--as, for instance, when she demonstrates the usefulness of monosyllables in poetry by illustrations from a series of poets beginning with Homer and ending with Swift. There can be little doubt that Swift is decisively worsted in this argument.

It is not known whether Swift ever read Miss Elstob’s Rudiments, though it is interesting to notice a marked change of emphasis in his references to the Anglo-Saxon language. In the Proposal he had declared with a pretense of knowledge, that Anglo-Saxon was “excepting some few variations in the orthography... the same in most original words with our present English, as well as with German and other northern dialects.” But in An Abstract of the History of England (probably revised in 1719) he says that the English which came in with the Saxons was “extremely different from what it is now.” The two statements are not incompatible, v but the emphasis is remarkably changed. It is possible that some friend had pointed out to Swift that his earlier statement was too gross a simplification, or alternatively that someone had drawn his attention to Elizabeth Elstob’s Rudiments.

All writers owe much to the labors of scholarship and are generally ill-advised to scorn or reject them, however uninspired and uninspiring they may seem. Moreover when authors do enter into dispute with “laborious men of low genius” they frequently meet with more than their match. Miss Elstob’s bold and aggressive defense of Northern antiquities was remembered and cited by a later scholar, George Ballard, as a warning to those who underestimated the importance of a sound knowledge of the language. Indeed, he wrote, “I thought that the bad success Dean Swift had met with in this affair from the incomparably learned and ingenious Mrs. Elstob would have deterred all others from once venturing in this affair.” (John Nichols, Illustrations of the Literary History of the Eighteenth Century, 1822, IV, 212.)

Charles Peake

University College, London

SIR,

OON after the Publication of the Homily on St.

Gregory, I was engaged by the Importunity of my Friends, to make a Visit

to Canterbury, as well to enjoy the Conversations of my Friends

and Relations there, as for that Benefit which I hoped to receive from

Change of Air, and freer Breathing, which is the usual Expectation of

those, who are used to a sedentary Life and Confinement in the great

City, and which renders such an Excursion

ii

now and then excusable. In this Recess, among the many Compliments and

kind Expressions, which their favourable Acceptance of my first Attempt

in Saxon, had obtained for me from the Ladies, I was more

particularly gratified, with the new Friendship and Conversation, of a

young Lady, whose Ingenuity and Love of Learning, is well known and

esteem’d, not only in that Place, but by your self: and which so far

indear’d itself to me, by her promise that she wou’d learn the Saxon

Tongue, and do me the Honour to be my Scholar, as to make

me think of composing an English Grammar of that Language for

her use. That Ladies Fortune hath so disposed of her since that time,

and hath placed her at so great distance, as that we have had no

Opportunity, of treating farther on this Matter, either by Discourse or

Correspondence. However though a Work of a larger Extent, and which hath

amply experienced your Encouragement, did for some time make me lay

aside this Design, yet I did not wholly reject it. For having re-assumed

this Task, and accomplish’d it in such manner at I was able, I now send

it to you, for your Correction, and that Stamp of Authority, it must

needs receive from a Person of such perfect and exact Judgement in these

Matters, in order to make it current, and worthy of Reception from the

Publick. Indeed I might well have spared my self the labour of such an

Attempt, after the elaborate Work of your rich and learned

Thesaurus, and the ingenious Compendium of it by Mr.

Thwaites; but considering the Pleasure I my self had reaped

from the Knowledge I have gained from this Original of our Mother

Tongue, and that others of my own Sex, might be capable of the same

Satisfaction: I resolv’d to give them the Rudiments of that Language in

an English Dress. However not ’till I

iii

B2

had communicated to you my Design for your Advice, and had receiv’d your

repeated Exhortation, and Encouragement to the Undertaking.

OON after the Publication of the Homily on St.

Gregory, I was engaged by the Importunity of my Friends, to make a Visit

to Canterbury, as well to enjoy the Conversations of my Friends

and Relations there, as for that Benefit which I hoped to receive from

Change of Air, and freer Breathing, which is the usual Expectation of

those, who are used to a sedentary Life and Confinement in the great

City, and which renders such an Excursion

ii

now and then excusable. In this Recess, among the many Compliments and

kind Expressions, which their favourable Acceptance of my first Attempt

in Saxon, had obtained for me from the Ladies, I was more

particularly gratified, with the new Friendship and Conversation, of a

young Lady, whose Ingenuity and Love of Learning, is well known and

esteem’d, not only in that Place, but by your self: and which so far

indear’d itself to me, by her promise that she wou’d learn the Saxon

Tongue, and do me the Honour to be my Scholar, as to make

me think of composing an English Grammar of that Language for

her use. That Ladies Fortune hath so disposed of her since that time,

and hath placed her at so great distance, as that we have had no

Opportunity, of treating farther on this Matter, either by Discourse or

Correspondence. However though a Work of a larger Extent, and which hath

amply experienced your Encouragement, did for some time make me lay

aside this Design, yet I did not wholly reject it. For having re-assumed

this Task, and accomplish’d it in such manner at I was able, I now send

it to you, for your Correction, and that Stamp of Authority, it must

needs receive from a Person of such perfect and exact Judgement in these

Matters, in order to make it current, and worthy of Reception from the

Publick. Indeed I might well have spared my self the labour of such an

Attempt, after the elaborate Work of your rich and learned

Thesaurus, and the ingenious Compendium of it by Mr.

Thwaites; but considering the Pleasure I my self had reaped

from the Knowledge I have gained from this Original of our Mother

Tongue, and that others of my own Sex, might be capable of the same

Satisfaction: I resolv’d to give them the Rudiments of that Language in

an English Dress. However not ’till I

iii

B2

had communicated to you my Design for your Advice, and had receiv’d your

repeated Exhortation, and Encouragement to the Undertaking.

The Method I have used, is neither entirely new, out of a Fondness and Affectation of Novelty: nor exactly the same with what has been in use, in teaching the learned Languages. I have retain’d the old Division of the Parts of Speech, nor have I rejected the other common Terms of Grammar; I have only endeavour’d to explain them in such a manner, as to hope they may be competently understood, by those whose Education, hath not allow’d them an Acquaintance with the Grammars of other Languages. There is one Addition to what your self and Mr. Thwaites have done on this Subject, for which you will, I imagine, readily pardon me: I have given most, if not all the Grammatical Terms in true old Saxon, from Ælfrick’s Translation of Priscian, to shew the polite Men of our Age, that the Language of their Forefathers is neither so barren nor barbarous as they affirm, with equal Ignorance and Boldness. Since this is such an Instance of its Copiousness, as is not to be found in any of the polite modern Languages; and the Latin itself is beholden to the Greek, not only for the Terms, but even the Names of Arts and Sciences, as is easily discerned in the Words, Philosophy, Grammar, Logick, Rhetorick, Geometry, Arithmetick, &c. These Gentlemens ill Treatment of our Mother Tongue has led me into a Stile not so agreeable to the Mildness of our Sex, or the usual manner of my Behaviour, to Persons of your Character; but the Love and Honour of one’s Countrey, hath in all Ages been acknowledged such a Virtue, as hath admitted of a Zeal even somewhat extravagant. Pro Patria mori, used to be one of the great Boasts of iv Antiquity; and even the so celebrated Magnanimity of Cato, and such others as have been called Patriots, had wanted their Praise, and their Admiration, had they wanted this Plea. The Justness and Propriety of the Language of any Nation, hath been always rightly esteem’d a great Ornament and Test of the good Sense of such a Nation; and consequently to arraign the good Sense or Language of any Nation, is to cast upon it a great Reproach. Even private Men are most jealous, of any Wound, that can be given them in their intellectual Accomplishments, which they are less able to endure, than Poverty itself or any other kind of Disgrace. This hath often occasion’d my Admiration, that those Persons, who talk so much, of the Honour of our Countrey, of the correcting, improving and ascertaining of our Language, shou’d dress it up in a Character so very strange and ridiculous: or to think of improving it to any degree of Honour and Advantage, by divesting it of the Ornaments of Antiquity, or separating it from the Saxon Root, whose Branches were so copious and numerous. But it is very remarkable how Ignorance will make Men bold, and presume to declare that unnecessary, which they will not be at the pains to render useful. Such kind of Teachers are no new thing, the Spirit of Truth itself hath set a mark upon them; Desiring to be Teachers of the Law, understanding neither what they say, nor whereof they affirm, 1 Tim. 1. 7. It had been well if those wise Grammarians had understood this Character, who have taken upon them to teach our Ladies and young Gentlemen, The whole System of an English Education; they had not incurr’d those Self-contradictions of which they are guilty; they had not mention’d your self, and your incomparable Treasury of Northern Literature in so cold v and negligent a manner, as betrays too much of an invidious Pedantry: But in those Terms of Veneration and Applause which are your just Tribute, not only from the Learned of your own Countrey, but of most of the other Northern Nations, whether more or less Polite: Who would any of them have glory’d in having you their Native, who have done so much Honour to the Original of almost all the Languages in Europe.

But it seems you are not of so much Credit with these Gentlemen, who question your Authority, and have given a very visible Proof of their Ingenuity in an Instance which plainly discovers, that they cannot believe their own Eyes.

“The Saxons, say they, if we may credit Dr. Hickes, had various Terminations to their Words, at least two in every Substantive singular: whereas we have no Word now in use, except the personal Names that has so. Thus Dr. Hickes has made six several Declensions of the Saxon Names: He gives them three Numbers; a Singular, Dual, and Plural: We have no Dual Number, except perhaps in Both: To make this plainer, we shall transcribe the six Declensions from that Antiquary’s Grammar.”

I would ask these Gentlemen, and why not credit Dr. Hickes? Is he not as much to be believ’d as those Gentlemen, who have transcribed so plain an Evidence of the six Declensions to shew the positive Unreasonableness and unwarrantable Contradiction of their Disbelief? Did he make those six Declensions? or rather, did he not find them in the Language, and take so much pains to teach others to distinguish them, who have Modesty enough to be taught? They are pleased to say we have no Word now in use that admits of Cases or Terminations. But let us ask them, what vi they think of these Words, God’s Word, Man’s Wisdom, the Smith’s Forge, and innumerable Instances more. For in God’s Word, &c. is not the Termination s a plain Indication of a Genitive Case, wherein the Saxon e is omitted? For example, Go?e? ?o??, Manne? ?i??om, ?miðe? Heo?ð. Some will say, that were better supplied by his, or hers, as Man his Thought, the Smith his Forge; but this Mistake is justly exploded. Yet if these Gentlemen will not credit Dr. Hickes, the Saxon Writings might give them full Satisfaction. The Gospels, the Psalms, and a great part of the Bible are in Saxon, so are the Laws and Ecclesiastical Canons, and Charters of most of our Saxon Kings; these one wou’d think might deserve their Credit. But they have not had Learning or Industry enough to fit them for such Acquaintance, and are forc’d therefore to take up their Refuge with those Triflers, whose only Pretence to Wit, is to despise their Betters. This Censure will not, I imagine, be thought harsh, by any candid Reader, since their own Discovery has sufficiently declared their Ignorance: and their Boldness, to determine things whereof they are so ignorant, has so justly fix’d upon them the Charge of Impudence. For otherwise they must needs have been ashamed to proceed in manner following.

“We might give you various Instances more of the essential difference between the old Saxon and modern English Tongue, but these must satisfy any reasonable Man, that it is so great, that the Saxon can be no Rule to us; and that to understand ours, there is no need of knowing the Saxon: And tho’ Dr. Hickes must be allow’d to have been a very curious Enquirer into those obsolete Tongues, now out of use, and containing nothing valuable, yet it does by no means follow (as is plain from what has been said) vii that we are obliged to derive the Sense, Construction, or Nature of our present Language from his Discoveries.”

I would beseech my Readers to observe, the Candour and Ingenuity of these Gentlemen: They tell us, We might give you various Instances more of the essential difference between the old Saxon and modern English Tongue; and yet have plainly made it appear, that they know little or nothing of the old Saxon. So that it will be hard to say how they come to know of any such essential difference, as MUST satisfy any reasonable Man; and much more that this essential difference is so great, that the Saxon can be no Rule to us, and that to understand ours, there is no need of knowing the Saxon. What they say, that it cannot be a Rule to them, is true; for nothing can be a Rule of Direction to any Man, the use whereof he does not understand; but if to understand the Original and Etymology of the Words of any Language, be needful towards knowing the Propriety of any Language, a thing which I have never heard hath yet been denied; then do these Gentlemen stand self-condemned, there being no less than four Words, in the Scheme of Declensions they have borrowed from Dr. Hickes, now in use, which are of pure Saxon Original, and consequently essential to the modern English. I need not tell any English Reader at this Day the meaning of Smith, Word, Son, and Good; but if I tell them that these are Saxon Words, I believe they will hardly deny them to be essential to the modern English, or that they will conclude that the difference between the old English and the modern is so great, or the distance of Relation between them so remote, as that the former deserves not to be remember’d: except by such Upstarts who having no Title to viii a laudable Pedigree, are backward in all due Respect and Veneration towards a noble Ancestry.

Their great Condescension to Dr. Hickes in allowing him to have been a very curious Inquirer into those obsolete Tongues, now out of use, and containing nothing valuable in them, is a Compliment for which I believe you, Sir, will give me leave to assure them, that he is not at all obliged; since if it signifies any thing, it imports, no less than that he has employ’d a great deal of Time, and a great deal of Pains, to little purpose. But we must at least borrow so much Assurance from them, as to tell them, that your Friends, who consist of the most learned sort of your own Countrey-men, and of Foreigners, do not think those Tongues so obsolete and out of use, whose Significancy is so apparent in Etymology; nor do they think those Men competent Judges to declare, whether there be any thing contained in them valuable or not, who have made it clear, that they know not what is contain’d in them. They would rather assure them, that our greatest ADivines, and BLawyers, and CHistorians are of another Opinion, they wou’d advise them to consult our Libraries, those of the two Universities, the Cottonian, and my Lord Treasurers; to study your whole Thesaurus, particularly your Dissertatio Epistolaris, to ix C look into Mr. Wanleys large and accurate Catalogue of Saxon Manuscripts, and so with Modesty gain a Title to the Applause of having confest their former Ignorance, and reforming their Judgment. I believe I may farther take leave to assure them, that the Doctor is as little concerned for their Inference, which they think so plain from what has been said, that they are not obliged to derive the Sense, Construction, or Nature of our present Language from his Discoveries. He desires them not to derive the Sense and Construction of which they speak, in any other manner, than that in which the Nature of the things themselves makes them appear; and so far as they are his Discoveries only, intrudes them on no Man. He is very willing they should be let alone by those, who have not Skill to use them to their own Advantage, and with Gratitude.

But to leave these Pedagogues to huff and swagger in the heighth of all their Arrogance. I cannot but think it great Pity, that in our Considerations, for Refinement of the English Tongue, so little Regard is had to Antiquity, and the Original of our present Language, which is the Saxon. This indeed is allow’d by an ingenious Person, who hath lately made some Proposals for the Refinement of the English Tongue, That the old Saxon, except in some few Variations in the Orthography, is the same in most original Words with our present English, as well as with the German and other Northern Dialects; which makes it a little surprizing to me, to find the same Gentleman not long after to say, The other Languages of Europe I know nothing of, neither is there any occasion to consider them: because, as I have before observ’d, it must be very difficult to imagin, how a Man can judge of a thing he knoweth nothing of, whether there can be x occasion or no to consider it. I must confess I hope when ever such a Project shall be taken in hand, for correcting, enlarging, and ascertaining our Language, a competent Number of such Persons will be advised with, as are knowing, not only in Saxon, but in the other Languages of Europe, and so be capable of judging how far those Languages may be useful in such a Project. The want of understanding this aright, wou’d very much injure the Success of such an Undertaking, and the bringing of it to Perfection; in denying that Assistance toward adjusting the Propriety of Words, which can only be had from the Knowledge of the Original, and likewise in depriving us of the Benefit of many useful and significant Words, which might be revived and recalled, to the Increase and Ornament of our Language, which wou’d be the more beautiful, as being more genuine and natural, by confessing a Saxon Original for their native Stock, or an Affinity with those Branches of the other Northern Tongues, which own the same Original.

The want of knowing the Northern Languages, has occasion’d an unkind Prejudice towards them: which some have introduced out of Rashness, others have taken upon Tradition. As if those Languages were made up of nothing else but Monosyllables, and harsh sounding Consonants; than which nothing can be a greater Mistake. I can speak for the Saxon, Gothick, and Francick, or old Teutonick: which for aptness of compounded, and well sounding Words, and variety of Numbers, are by those learned Men that understand them, thought scarce inferior to the Greek itself. I never cou’d find my self shocked with the Harshness of those Languages, which grates so much in the Ears of those that never heard them. I never perceiv’d in the xi C2 Consonants any Hardness, but such as was necessary to afford Strength, like the Bones in a human Body, which yield it Firmness and Support. So that the worst that can be said on this occasion of our Forefathers is, that they spoke at they fought, like Men.

The Author of the Proposal, may think this but an ill Return, for the soft things he has said of the Ladies, but I think it Gratitude at least to make the Return, by doing Justice to the Gentlemen. I will not contradict the Relation of the ingenious Experiment of his vocal Ladies, tho’ I could give him some Instances to the contrary, in my Experience of those, whose Writings abound with Consonants; where Vowels must generally be understood, and appear but very rarely. Perhaps that Gentleman may be told that I have a Northern Correspondence, and a Northern Ear, probably not so fine as he may think his own to be, yet a little musical.

And now for our Monosyllables. In the Controversy concerning which, it must be examined, first whether the Charge which is exhibited against the Northern Languages is true, that they consist of nothing but Monosyllables; and secondly, whether or no the Copiousness and Variety of Monosyllables may be always justly reputed a fault, and may not sometimes as justly be thought, to be very useful and ornamental.

And first I must assert, that the ancient Northern Languages, do not wholly nor mostly consist of Monosyllables. I speak chiefly of the Gothick, Saxon, and Teutonick. It must be confest that in the Saxon, there are many Primitive Words of one Syllable, and this to those who know the Esteem that is due to Simplicity and Plainness, in any Language, will rather be judged a Virtue than a Vice: That is, that the first Notions of things should be exprest in the plainest and simplest xii manner, and in the least compass: and the Qualities and Relations, by suitable Additions, and Composition of Primitive WordsD; for which the Saxon Language is very remarkable, as has been before observed, and of which there are numerous Examples, in the following Treatise of Saxon Grammar, and infinitely more might have been added.

The second Enquiry is, whether or no the Copiousness and Variety of Monosyllables may be always justly reputed a fault, and may not as justly be thought, to be very useful and ornamental? Were this a fault, it might as justly be charged upon the learned Languages, the Latin and Greek: For the Latin you have in Lilly’s Rules concerning Nouns, several Verses, made up for the most part of Monosyllables, I mention him not as a Classick, but because the Words are Classical and Monosyllables; and in the Greek there are several as it were, idle Monosyllables, that have little Significancy, except to make the Numbers in Verse compleat, or to give a Fulness to their Periods, as the Verses of Homer and other Greek Poets plainly evidence: An Instance or two may suffice;

?? ?? d? ta p??ta d?ast?t?? ???sa?te.

Here are four Monosyllables in this Verse,

??? d’ ??? ?? ??s?, p??? µ?? ?a? ???a? ?pe?se?.

Here are six Monosyllables, and one cutting off.

xiii???’ ???, µ? µ’ ??????e, sa?te??? ?? ?e ???a?.

?? ?d? t? t’ ???ta, t? t’ ?ss?µe?a p?? t‘ ???ta.

Here are seven Monosyllables; yet so far is Virgil from being angry with his Master Homer on this Account, that he in a manner transcribes his very Words, imitating him as near as the Latin wou’d permit;

Quæ sint, quæ fuerint, quæ mox ventura trahantur.

Here is the whole Sense of Homer exprest, and five Monosyllables. But Mr. Dryden, who has exprest the Sense of Virgil with no less Accuracy, gives you the whole Line in Monosyllables;

He sees what is, and was, and is to come.

Mr. Pope is equally happy in the Turn he has given to the Original, who as he is an exact Master of Criticism, so has he all those Accomplishments of an excellent Poet, that give us just Reason to hope he will make the Father of the Poets speak to us in our own Language, with all the Advantages he gave to his Works in that wherein they were first written, and the modest Opinion he prescribes to his own, and other Mens Poetical Performances, is no Discouragement to these Hopes;

Whoever thinks a faultless Piece to see,

Thinks what ne’er was, nor is, nor e’er shall be.

And Horace, while he is teaching us the Beauties in the Art of Poetry, gives no less than nine Monosyllables in the compass of a Verse and a half;

Sed nunc non erat his locus: & fortasse cupressum

Scis simulare. Quid hoc si, &c.

Now if these are Beauties, as I doubt not but the politer Criticks will allow, I cannot see why our Language may not now and then be tolerated in using Monosyllables, when it is done discreetly, and sparingly; and as I do not commend any of our Moderns who contract Words into Monosyllables to botch up their Verses, much less such as do it out of Affectation; yet certainly the use of Monosyllables may be made to produce a charming and harmonious Effect, where they fall under a Judgment that can rightly dispose and order them. And indeed, if a Variety and Copiousness of Feet, and a Latitude of shifting and transposing Words either in Prose or Poetical Compositions, be of any use, towards the rendering such Compactions sweet, or nervous, or harmonious, according to the Exigencies of the several sorts of Stile, one wou’d think Monosyllables to be best accommodated to all these Purposes, and according to the Skill of those who know how to manage them, to answer all the Ends, either of masculine Force, or female Tenderness; for being single you have a Liberty of placing them where, and as you please; whereas in Words of many Syllables you are more confined, and must take them as you find them, or be put upon the cruel necessity of mangling and tearing them asunder. Mr. Dryden, it is true, wou’d make us believe he had a great Aversion to Monosyllables. Yet he cannot help making use of them sometimes in entire Verses, nor conceal his having a sort of Pride, even where he tells us he was forc’d to do it. For to have done otherwise would have been a Force on Nature, which would have been unworthy of so great a Genius, whose Care it was to study Nature, and to imitate and copy it to the Life; and it is not improbable, that there might be somewhat of a latent Delicacy and Niceness in this xv Matter, which he chose rather to dissemble, than to expose, to the indiscreet Management of meaner Writers. For in the first Line of his great Work the Æneis, every Word is a Monosyllable; and tho’ he makes a seeming kind of Apology, yet he cannot forbear owning a secret Pleasure in what he had done. “My first Line in the Æneis, says he, is not harsh.

“Arms and the Man I sing, who forc’d by Fate.

“But a much better Instance may be given from the last Line of Manilius, made English by our learned and judicious Mr. Creech;

“Nor could the World have born so fierce a Flame.

“Where the many liquid Consonants are placed so artfully, that they give a pleasing Sound to the Words, tho’ they are all of one Syllable.”

It is plain from these last Words, that the Subject-matter, Monosyllables, is not so much to be complain’d of; what is chiefly to be requir’d, is of the Poet, that he be a good Workman, in forming them aright, and that he place them artfully: and, however Mr. Dryden may desire to disguise himself, yet, as he some where says, Nature will prevail. For see with how much Passion he has exprest himself towards these two Verses, in which the Poet has not been sparing of Monosyllables: “I am sure, says he, there are few who make Verses, have observ’d the Sweetness of these two Lines in Coopers Hill;

“Tho deep, yet clear; tho gentle, yet not dull;

“Strong without Rage, without o’erflowing full.

“And there are yet fewer that can find the reason of that Sweetness, I have given it to some of my Friends in Conversation, and they have allow’d the Criticism to be just.”

You see, Sir, this great Master had his Reserves, and this was one of the Arcana, to which every Novice was not admitted to aspire; this was an Entertainment only for his best Friends, such as he thought worthy of his Conversation; and I do not wonder at it, for he was acquainted not only with the Greek and Latin Poets, but with the best of his own Countrey, as well of ancient as of latter times, and knew their Beauties and Defects: and tho’ he did not think himself obliged to be lavish, in dispersing the Fruits of so much Pains and Labour at random, yet was he not wanting in his Generosity to such as deserved his Friendship, and in whom he discern’d a Spirit capable of improving the Hints of so great a Master. To give greater Probability to what I have said concerning Monosyllables, I will give some Instances, as well from such Poets as have gone before him, as those which have succeeded him. It will not be taken amiss by those who value the Judgment of Sir Philip Sydney, and that of Mr. Dryden, if I begin with Father Chaucer.

Er it was Day, as was her won to do.

Again,

And but I have her Mercy and her Grace,

That I may seen her at the lefte way;

I nam but deed there nis no more to say.

Again,

Alas, what is this wonder Maladye?

For heate of colde, for colde of heate I dye.

And since we are a united Nation, and he as great a Poet, considering his time, as this Island hath produced, I will with due Veneration for his Memory, beg leave to cite the learned and noble Prelate, Gawen Douglas, Bishop of Dunkeld in Scotland, who in his Preface to his judicious and accurate Translation of Virgil, p. 4. says,

Nane is, nor was, nor zit sal be, trowe I,

Had, has, or sal have, sic craft in Poetry:

Again, p. 5.

Than thou or I, my Freynde, quhen we best wene.

But before, at least contemporary with Chaucer, we find Sir John Gower, not baulking Monosyllables;

Myne Herte is well the more glad

To write so as he me bad,

And eke my Fear is well the lasse.

King Salomon which had at his asking

Of God, what thyng him was leuest crave.

He chase Wysedom unto governyng

Of Goddes Folke, the whiche he wolde save:

And as he chase it fyl him for to have.

xviiiFor through his Witte, while that his Reigne laste,

He gate him Peace, and Rest, into his laste.

Again,

Peace is the chefe of al the Worldes Welth,

And to the Heven it ledeth eke the way,

Peace is of Soule and Lyfe the Mannes Helth,

Of Pestylence, and doth the Warre away,

My Liege Lord take hede of that I say.

If Warre may be lefte, take Peace on Hande

Which may not be without Goddes Sande.E

Nor were the French, however more polite they may be thought, than we are said to be, more scrupulous in avoiding them, if these Verses are upon his Monument;

En toy qui es fitz de Dieu le Pere,

Sauue soit, qui gist sours cest pierre.

This will be said to be old French, let us see whether Boileau will help us out, who has not long since writ the Art of Poetry;

xix D2Mais moi, grace au Destin, qui n’ai ni feu ne lieu,

Je me loge où je puis, & comme il plaist à Dieu.

And in that which follows,

Et tel, en vous lisant, admire chaque traite,

Qui dans le fond de l’ame, & vous craint & vous hait.

Let Lydgate, Chaucer’s Scholar also be brought in for a Voucher;

For Chaucer that my Master was and knew

What did belong to writing Verse and Prose,

Ne’er stumbled at small faults, nor yet did view

With scornful Eye the Works and Books of those

That in his time did write, nor yet would taunt

At any Man, to fear him or to daunt.

Tho’ the Verse is somewhat antiquated, yet the Example ought not to be despised by our modern Criticks, especially those who have any Respect for Chaucer.

I might give more Instances out of John Harding, and our good old Citizen, Alderman Fabian, besides many others: but out of that Respect to the nice Genij of our Time, which they seldom allow to others, I will hasten to the Times of greater Politeness, and desire that room may be made, and attention given to a Person of no less Wit than Honour, the Earl of Surrey, who at least had all the Elegancy of a gentle Muse, that may deserve the Praises of our Sex,

Her Praise I tune whose Tongue doth tune the Spheres,

And gets new Muses in her Hearers Ears.

Stars fall to fetch fresh Light from her rich Eyes,

Her bright Brow drives the Sun to Clouds beneath.

Again,

O Glass! with too much Joy my Thoughts thou greets.

And again upon the Chamber where his admired Geraldine was born;

O! if Elyzium be above the Ground,

Then here it is, where nought but Joy is found.

And Michael Drayton, who had a Talent fit to imitate, and to celebrate so great a Genius, of all our English Poets, seems best to have understood the sweet and harmonious placing of Monosyllables, and has practised it with so great a Variety, as discovers in him a peculiar Delight, even to Fondness; for which however, I cannot blame him, notwithstanding this may be reputed the Vice of our Sex, and in him be thought effeminate. But let the Reader judge for himself;

Care draws on Care, Woe comforts Woe again,

Sorrow breeds Sorrow, one Griefe brings forth twaine,

If live or dye, as thou doost, so do I,

If live, I live, and if thou dye, I dye;

One Hart, one Love, one Joy, one Griefe, one Troth,

One Good, one Ill, one Life, one Death to both.

Again,

Where as thou cam’st unto the Word of Love,

Even in thine Eyes I saw how Passion strove;

That snowy Lawn which covered thy Bed,

Me thought lookt white, to see thy cheeke so red,

Thy rosye cheeke oft changing in my sight,

Yet still was red to see the Lawn so white:

xxiThe little Taper which should give the Light,

Me thought waxt dim, to see thy Eye so bright.

Again,

Your Love and Hate is this, I now do prove you,

You Love in Hate, by Hate to make me love you.

And to the Countess of Bedford, one of his great Patronesses;

Sweet Lady yet, grace this poore Muse of mine,

Whose Faith, whose Zeal, whose Life, whose All is thine.

The next that I shall mention, is taken out of an ingenious Poem, entituled, The Tale of the Swans, written by William Vallans in blank Verse in the time of Queen Elizabeth; for the reprinting of which, we are obliged to that ingenious and most industrious Preserver and Restorer of Antiquities, Mr. Thomas Hearne of Oxford;

Among the which the merrie Nightingale

With swete, and swete (her Brest again a Thorne.)

In another Place,

And in the Launde, hard by the Parke of Ware

Afterwards,

To Ware he comes, and to the Launde he flies.

Again,

And in this Pompe they hie them to the Head.

xxiiI come now to the incomparable Spencer, against whose Judgment and Practice, I believe scarce any Man will be so bold as to oppose himself;

Assure your self; it fell not all to Ground;

For all so dear as Life is to my Heart,

I deem your Love, and hold me to you bound.

Again,

Go say his Foe thy Shielde with his doth bear.

Afterwards,

More old than Jove, whom thou at first didst breed.

And,

And now the Prey of Fowls in Field he lies.

Nor must Ben. Johnson be forgotten;

Thy Praise or Dispraise is to me alike;

One doth not stroke me, nor the other strike.

Again,

Curst be his Muse, that could lye dumb, or hid

To so true Worth, though thou thy self forbid.

In this Train of Voters for Monosyllables, the inimitable Cowley marches next, whom we must not refuse to hear;

Yet I must on; what Sound is’t strikes mine Ear?

Sure I Fames Trumpet hear.

And a little after,

Come my best Friends, my Books, and lead me on;

’Tis time that I were gone.

xxiiiWelcome, great Stagirite, and teach me now

All I was born to know.

And commending Cicero, he says,

Thou art the best of Orators; only he

Who best can praise thee, next must be.

And of Virgil thus,

Who brought green Poesy to her perfect Age,

And made that Art, which was a Rage.

And in the beginning of the next Ode, he wou’d not certainly have apply’d himself to WIT in the harsh Cadence of Monosyllables, had he thought them so very harsh;

Tell me, O tell, what kind of thing is Wit,

Thou who Master art of it.

Again,

In a true Piece of Wit all things must be

Yet all things there agree.

But did he believe such Concord to be inconsistent with the use of Monosyllables, he had surely banished them from these two Lines; and were I to fetch Testimonies out of his Writings, I might pick a Jury of Twelve out of every Page.

And now comes Mr. Waller, and what does he with his Monosyllables, but,

Give us new Rules, and set our Harp in Tune.

And that honourable Peer whom he commends, the Lord Roscommon thus keeps him in Countenance;

Be what you will, so you be still the same.

xxivAnd again,

In her full Flight, and when she shou’d be curb’d.

Soon after,

Use is the Judge, the Law, and Rule of Speech,

And by and by,

We weep and laugh, as we see others do,

He only makes me sad who shews the way:

But if you act them ill, I sleep or laugh.

The next I shall mention is my Lord Orrery, who, as Mr. Anthony Wood says, was a great Poet, Statesman, Soldier, and great every thing which merits the Name of Great and Good. In his Poem to Mrs. Philips, he writes thus;

For they imperfect Trophies to you raise,

You deserve Wonder, and they pay but Praise;

A Praise which is as short of your great due.

As all which yet have writ come short of you.

Again,

In Pictures none hereafter will delight,

You draw more to the Life in black and white;

The Pencil to your Pen must yield the Place,

This draws the Soul, where that draws but the Face.

But having thank’d these noble Lords for their Suffrage, we will proceed to some other Witnesses of Quality: And first I beg leave to appeal to my Lord Duke of Buckinghamshire, his Translation of The Temple of Death;

xxv EHer Chains were Marks of Honour to the Brave,

She made a Prince when e’er she made a Slave.

Again,

By wounding me, she learnt the fatal Art,

And the first Sigh she had, was from my Heart.

My Lord Hallifax’s Muse hath been very indulgent to Monosyllables, and no Son of Apollo will dare to dispute his Authority in this Matter. Speaking of the Death of King Charles the Second, and his Improvement of Navigation, and Shipping; he says,

To ev’ry Coast, with ready Sails are hurl’d,

Fill us with Wealth, and with our Fame the World.

Again,

Us from our Foes, and from our selves did shield.

Again,

As the stout Oak, when round his Trunk the Vine

Does in soft Wreaths, and amorous Foldings twine.

And again,

In Charles, so good a Man and King, we see,

A double Image of the Deity.

Oh! Had he more resembled it! Oh why

Was he not still more like; and cou’d not die?

My Lord Landsdown’s Muse, which may claim her Seat in the highest Point of Parnassus, gives us these Instances of her Sentiments in our Favour;

So own’d by Heaven, less glorious far was he,

Great God of Verse, than I, thus prais’d by thee.

Again on Mira’s singing,

The Slave that from her Wit or Beauty flies,

If she but reach him with her Voice, he dies.

In such noble Company, I imagin Mr. Addison will not be ashamed to appear, thus speaking of Mr. Cowley;

His Turns too closely on the Reader press;

He more had pleas’d us, had he pleas’d us less.

And of Mr. Waller,

Oh had thy Muse not come an Age too soon.

And of Mr. Dryden’s Muse,

Whether in Comick Sounds or Tragick Airs

She forms her Voice, she moves our Smiles or Tears.

And to his Friend Dr. Sacheverell,

I’ve done at length, and now, dear Friend, receive

The last poor Present that my Muse can give.

And so at once, dear Friend and Muse, fare well.

To these let me add the Testimony of that Darling of the Muses, Mr. Prior, with whom all the Poets of ancient and modern Times of other Nations, or our own, might seem to have intrusted the chief Secrets, and greatest Treasures of their Art. I shall speak only concerning our own Island, where his Imitation of Chaucer, of Spencer, and of the old Scotch Poem, inscribed the Nut-Brown Maid, shew how great a Master he is, and how much every thing is to be valued which bears the Stamp of his Approbation. And we shall certainly find a great deal to countenance the use of Monosyllables in his Writings. Take these Examples;

xxvii E2Me all too mean for such a Task I weet.

Again,

Grasps he the Bolt? we ask, when he has hurl’d the Flame.

And,

Nor found they lagg’d too slow, nor flew too fast.

And again,

With Fear and with Desire, with Joy and Pain

She sees and runs to meet him on the Plain.

And,

With all his Rage, and Dread, and Grief, and Care.

In his Poem in answer to Mrs. Eliz. Singer, on her Poem upon Love and Friendship,

And dies in Woe, that thou may’st live in Peace.

The only farther Example of Monosyllabick Verses I shall insert here, and which I cannot well omit, is what I wou’d desire the Author to apply to his own Censure of Monosyllables, they are these which follow;

Then since you now have done your worst,

Pray leave me where you found me first.

Part of the seventh Epistle of the first Book of Horace imitated, and address’d to a noble Peer, p. ult.

After so many Authorities of the Gentlemen, these few Instances from some of our Female Poets, may I hope be permitted to take place. I will begin with Mrs. Philips on the Death of the Queen of Bohemia;

Over all Hearts and her own Griefs she reign’d.

xxviiiAnd on the Marriage of the Lord Dungannon,

May the vast Sea for your sake quit his Pride,

And grow so smooth, while on his Breast you ride,

As may not only bring you to your Port,

But shew how all things do your Virtues court.

To Gilbert Lord Archbishop of Canterbury,

That the same Wing may over her be cast,

Where the best Church of all the World is plac’d.

Mrs. Wharton upon the Lamentations of Jeremiah;

Behold those Griefs which no one can repeat,

Her Fall is steep, and all her Foes are great.

And my Lady Winchelsea in her Poem entituled, The Poor Man’s Lamb;

Thus wash’d in Tears, thy Soul as fair does show

As the first Fleece, which on the Lamb does grow.

Sir, from these numerous Instances, out of the Writings of our greatest and noblest Poets, it is apparent, That had the Enmity against Monosyllables, with which there are some who make so great a Clamour, been so great in all Times, we must have been deprived of some of the best Lines, and finest Flowers, that are to be met with in the beautiful Garden of our English Posie. Perhaps this may put our Countreymen upon studying with greater Niceness the use of these kind of Words, as well in the Heroick Compositions, as in the softer and more gentle Strains. I speak not this, upon Confidence of any Judgment I have in Poetry, but according to that Skill, which is natural to the Musick xxix of a Northern Ear, which, if it be deficient, as I shall not be very obstinate in its Defence, I beg leave it may at least be permitted the Benefit of Mr. Dryden’s Apology, for the Musick of old Father Chaucer’s Numbers, “That there is the rude Sweetness of a Scotch Tune in it, which is natural and pleasing, tho’ not perfect.”

Sir, I must beg your Pardon for this long Digression, upon a Subject which many will think does not deserve it: but if I have herein discover’d some of the greatest Beauties of our English Poets, it will be more excusable, at least for the respect that is intended to so noble an Art as theirs. But to suspect the worst, considering that I am now writing a Preface, I am provided with another Apology from Mr. Dryden, who cautions his Reader with this Observation, That the Nature of a Preface is Rambling, never wholly out of the way, nor in it. Yet I cannot end this Preface, without desiring that such as shall be employ’d in refining and ascertaining our English Tongue, may entertain better Thoughts both of the Saxon Tongue, and of the Study of Antiquities. Methinks it is very hard, that those who labour and take so much pains to furnish others with Materials, either for Writing, or for Discourse, who have not Leisure, or Skill, or Industry enough to serve themselves, shou’d be allowed no other Instances of Gratitude, than the reproachful Title of Men of low Genius, of which low Genius’s it may be observed, that they carry some Ballast, and some valuable Loading in them, which may be despised, but is seldom to be exceeded in any thing truly valuable, by light and fluttering Wits. But it is not to be wonder’d, that Men of Worth are to be trampled upon, for otherwise they might stand in the way of these Assumers; and indeed were it not for the Modesty of their Betters, xxx and their own Assurance, they wou’d not only be put out of the way of those Expectations that they have, but out of all manner of Countenance. There is a Piece of History that I have met with in the Life of Archbishop Spotswood, that may not unfitly be remembered on this Occasion, shewing that studious Men of a private Character are not always to be reputed Men of low Genius:

“Nor were his Virtues (says the History) buried and confined within the Boundaries of his Parish, for having formerly had a Relation to the noble Family of Lenox, he was looked upon as the fittest Person of his Quality to attend Lodowic, Duke of Lenox, as his Chaplain in that honourable Embassy to Henry the fourth of France, for confirming the ancient Amity between both Nations; wherein he so discreetly carried himself, as added much to his Reputation, and made it appear that Men bred up in the Shade of Learning might possibly endure the Sun-shine, and when it came to their turns, might carry themselves as handsomly abroad, as they (whose Education being in a more pragmatick way) usually undervalue them.”

But that of low Genius is not the worst Charge which is brought against the Antiquaries, for they are not allow’d to have so much as common Sense, or to know how to express their Minds intelligibly. This I learn from a Dissertation on reading the Classicks, and forming a just Stile; where it is said, “It must be a great fault of Judgment if where the Thoughts are proper, the Expressions are not so too: A Disagreement between these seldom happens, but among Men of more recondite Studies, and what they call deep Learning, especially among your Antiquaries and Schoolmen.” This is a good careless way of talking, it may pass well enough for the genteel Negligence, in xxxi short, such Nonsense, as Our Antiquaries are seldom guilty of; for Propriety of Thoughts, without Propriety of Expression is such a Discovery, as is not easily laid hold of, except by such Hunters after Spectres and Meteors, as are forced to be content with the Froth and Scum of Learning, but have indeed nothing to shew of that deep Learning, which is the effect of recondite Studies. And there was a Gentleman, no less a Friend to polite Learning, but as good a judge of it as himself, and who is also a Friend to Antiquities, who was hugely pleased with the Humour of his saying Your Antiquaries, being very ready to disclaim an Acquaintance with all such Wits, and who told me the Antiquaries, were the Men in all the World who most contemn’d Your Men of Sufficiency and Self-conceit. But here his Master Horace is quite slipt out of his Mind, whose Words are,

Scribendi recte, sapere est & principium & fons.

Rem tibi Socraticæ poterunt ostendere chartæ:

Verbaque provisam rem non invita sequentur.

Thus translated by my Lord Roscommon,

Sound Judgment is the ground of writing well:

And when Philosophy directs your Choice

To proper Subjects rightly understood,

Words from your Pen will naturally flow.

Horace’s Sapere, and my Lord Roscommon’s Proper Subjects rightly understood, I take to be the same as Propriety of Thought, and the non invita sequentur, naturally flowing, I take to import the Fitness and Propriety of Expression. I also gather from hence, that xxxii there is a very easy and natural Connexion between these two, and these same Antiquaries of OURS, must be either very dull and stupid Animals, or a strange kind of cross-gran’d and perverse Fellows, to be always putting a Force upon Nature, and running out of a plain Road. He must either insinuate that they are indeed such, or that Horace’s Observation is not just, or that for the Word invita we ought to have a better reading, for which he will be forced to consult the Antiquaries. I know not how some of the great Orators, he has mention’d, will relish his Compliments upon the Score of Eloquence, when he has said such hard things against Antiquaries; many of them, and those of chief Note, were his Censure just and universal, must of necessity be involv’d in it. For example, the late Bishop of Rochester, of whom, he says, “He was the correctest Writer of the Age, and comes nearest the great Originals of Greece and Rome, by a studious Imitation of the Ancients.” So that, as I take it, he was an Antiquary: If he excludes English Antiquities, I desire him to remember the present Bishop of Rochester, of whom he has given this true Character, “Dr. Atterbury writeth with the fewest Faults, and greatest Excellencies of any who have studied to mix Art and Nature in their Compositions, &c.” He hath however thought fit to adorn the Subject of Antiquities with the Beauties of his Stile, without any Force upon Nature, or the being obliged to forsake her easy and unconstrain’d Method of applying proper Expressions to proper Thoughts. The Bishop of St. Asaph hath shewn his Skill in Antiquities, by more Instances than one; yet do I not find, that even in the Opinion of this Gentleman, it hath spoil’d his Stile. I shall add to these the late and present Bishops of Worcester, the former, xxxiii F Dr. Stillingfleet, is allow’d by all to have been one of the most learned Men and greatest Antiquaries of his Age; and for the present Bishop, who is also a learned Antiquary, take the Character which is given of his Skill and Exactness in the English Tongue from FBishop Wilkins; “I must acknowledge my self obliged, saith he, to the continual Assistance I have had from my most learned and worthy Friend, Dr. William Lloyd, than whom (so far as I am able to judge) this Nation could not have afforded a fitter Person, either for that great Industry, or accurate Judgment, both in Philological, and Philosophical Matters, required to such a Work. And particularly, I must wholly ascribe to him that tedious and difficult Task, of suiting the Tables to the Dictionary, and the drawing up of the Dictionary itself, which, upon trial, I doubt not, will be found to be the most perfect, that was ever yet made for the English Tongue.” I will only farther beg leave to mention, the Bishop of Carlisle, Your Self, and Dr. Gibson, who for good Spirit, masterly Judgment, and all the Ornaments of Stile, in the several ways of Writing, may be equalled with the best and most polite. To conclude, if this Preface is writ in a Stile, that may be thought somewhat rough and too severe, it is not out of any natural Inclination to take up a Quarrel, but to do some Justice to the Study of Antiquities, and even of our own Language itself, against the severe Censurers of both; whose Behaviour in this Controversy has been such, as cou’d not have the Treatment it deserved in a more modest or civil manner. If I am mistaken herein, I beg Pardon: I might alledge that which perhaps xxxiv might be admitted for an Excuse, but that I will not involve the whole Sex, by pleading Woman’s Frailty. I confess I thought it would be to little purpose to write an English Saxon Grammar, if there was nothing of Worth in that Language to invite any one to the study of it; so that I have only been upon the Defensive. If any think fit to take up Arms againsst me, I have great Confidence in the Protection of the Learned, the Candid, and the Noble; amongst which, from as many as bear the Ensigns of St. George, I cannot doubt of that help, that true Chevalrie can afford, to any Damsel in Distress, by cutting off the Heads of all those Dragons, that dare but to open their Mouths, or begin to hiss against her. But, Sir, before I conclude, I must do you the Justice to insert an extract of two Letters from the Right Honourable D. P. to the Reverend Dr. R. Taylor, relating to your Thesaurus. Lingg. Vett. Septentrion. which indeed might more properly have been placed in the eighth Page of this Preface, had it come sooner to my Hands. It is as follows,

——“The Dean’s Present, which I shall value as long as I live for his sake. Dom. Mabillon was the first that told me of that Work, and said, that the Author was a truly learned Person, and not one of those Writers who did not understand their Subject to the bottom, but, said he, that learned Man is one of ten thousand.”

And in another Letter to the abovemention’d Dr. Taylor———. “When Dom. Mabillon first told me of it, he did not name the Author, so as I understood who he was, but the Elogium he made of him, was indeed very great, and I find that the Dean in one Word, has done that worthy Man Justice.” This high Elogium of your self, and of your great Work, xxxv from so renowned an Antiquary, as it is a great Defence and Commendation of the Old Northern Learning, so is it the more remarkable, in that it was given by one, against whom you had written in the most tender Point of the Controversy, De Re Diplomatica, as may be seen in your Lingg. Vett. Septentr. Thesaur. Præfat. General. p. xxxvi, &c.

Sir, I once more heartily beg your Pardon for giving you so much trouble, and beg leave to give you my Thanks for the great Assistance I have received in the Saxon Studies from your learned Works, and Conversation; and in particular for your favourable Recommendation of my Endeavours, in a farther cultivating those Studies, who with sincere Wishes for your good Health, and all imaginable Respect for a Person of your Worth and Learning, am,

SIR,

Your Most Obliged,

Humble Servant,

Elizabeth Elstob.

A. Archbishops Parker, Laud, Usher, Bishop Stillingfleet, the present Bishops of Worcester, Bath and Wells, Carlisle, St. Asaph, St. Davids, Lincoln, Rochester, with many other Divines of the first Rank.

B. The Lord Chief Justice Cook, Mr. Lombard, Selden, Whitlock, Lord Chief Justice Hales, and Parker, Mr. Fortescue of the Temple, and others.

C. Leland, who writes in a Latin Style in Prose and Verse, as polite and accurate as can be boasted of by any of our-modern Wits. Jocelin, Spelman, both Father and Son, Cambden, Whelock, Gibson, and many more of all Ranks and Qualities, whose Names deserve well to be mention’d with Respect, were there room for it in this place.

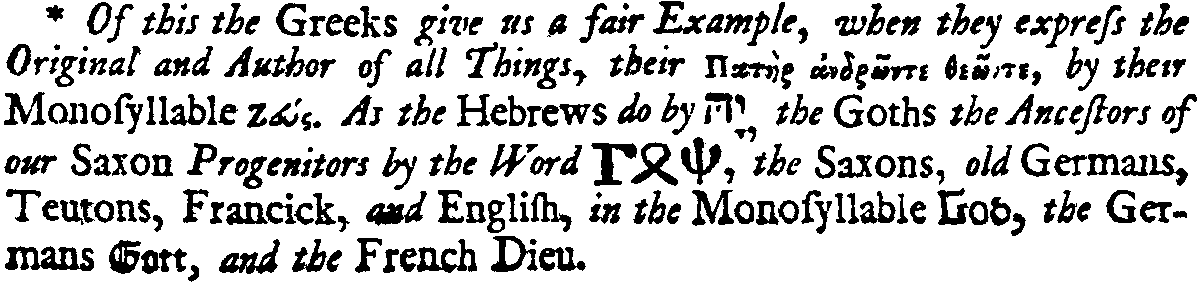

D. Of this the Greeks give as a fair Example, when they express the Original and Author of all Things, their ?at?? ??d???te ?e??te, by their Monosyllable ?e??. As the Hebrews do by ??, the Goths the Ancestors of our Saxon Progenitors by the Word ??????, the Saxons, old Germans, Teutons, Francick, and English, in the Monosyllable Go?, the Germans Gott, and the French Dieu. Page image

E. Besides the Purpose for which these Verses are here cited, it may not be amiss to observe from some Instances of Words contain’d in them, how necessary, at least useful, the Knowledge of the Saxon Tongue is, to the right understanding our Old English Poets, and other Writers. For example, leuest, this is the same with the Saxon leo?o??, most beloved, or desirable. Goddes folke, not God his Folk, this has plainly the Remains of the Saxon Genitive Case. Sande, this is a pure Saxon word, signifying Mission, or being sent. See the Saxon Homily on the Birth Day of St. Gregory, p. 2. He ðu?h hi? ?æ?e ? ?an?e u? ??am ðeo?le? bi??en?um æ?b?æ?. He through his Counsel and Commission rescued us from the Worship of the Devil.

F. See the Epistle to the Reader in the Essay towards a Real Character, p. 3.

|

R. C. Boys |

Vinton A. Dearing |

|

Ralph Cohen |

Lawrence Clark Powell |

| Corresponding Secretary: Mrs. Edna C. Davis, Wm. Andrews Clark Memorial Library | |

The Society exists to make available inexpensive reprints (usually facsimile reproductions) of rare seventeenth and eighteenth century works. The editorial policy of the Society remains unchanged. As in the past, the editors welcome suggestions concerning publications. All income of the Society it devoted to defraying cost of publication and mailing.

All correspondence concerning subscriptions in the United States and Canada should be addressed to the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, 2205 West Adams Boulevard, Los Angeles 18, California. Correspondence concerning editorial matters may be addressed to any of the general editors. The membership fee is $3.00 a year for subscribers in the United States and Canada and 15/- for subscribers in Great Britain and Europe. British and European subscribers should address B. H. Blackwell, Broad Street, Oxford, England.

Many of the listed titles are available from Project Gutenberg. Where possible, links are included.

An Essay on the New Species of Writing Founded by Mr. Fielding (1751). Introduction by James A. Work.

Elizabeth Elstob, An Apology for the Study of Northern Antiquities (1715). Introduction by Charles Peake.

G. W. Magazine, or Animadversions on the English Spelling (1703). Anon., The Needful Attempt, to make Language and Divinity Plain and Easie (1711). Introduction by David Abercrombie. e-text 20130 (Year 14)

Prefaces to Fiction. Selected, with an introduction, by Claude E. Jones.

Samuel Johnson. Notes to Shakespeare, Vol. II, Histories. Edited by Arthur Sherbo. (A double issue)

Parodies of Ballad Criticism. Selected, with an introduction, by William K. Winsatt, Jr. e-text 22081

Two Funeral Sermons. Selected, with an introduction, by Frank L. Huntley.

Richard Savage, An Author to be Let (1732). Introduction by James Sutherland.

Publications for the first ten years (with the exception of Nos. 1-6, which are out of print) are available at the rate of $3.00 a year. Prices for individual numbers may be obtained by writing to the Society.

Make check or money order payable to The Regents of the University of California.

Numbers 1-6 out of print.

7. John Gay’s The Present State of Wit (1711); and a section on Wit from The English Theophrastus (1702).

8. Rapin’s De Carmine Pastorali, translated by Creech (1684).

9. T. Hanmer’s (?) Some Remarks on the Tragedy of Hamlet (1736).

10. Corbyn Morris’ Essay towards Fixing the True Standards of Wit, etc. (1744).

11. Thomas Purney’s Discourse on the Pastoral (1717).

12. Essays on the Stage, selected, with an Introduction by Joseph Wood Krutch.

13. Sir John Falstaff (pseud.), The Theatre (1720).

14. Edward Moore’s The Gamester (1753).

15. John Oldmixon’s Reflections on Dr. Swift’s Letter to Harley (1712); and Arthur Mainwaring’s The British Academy (1712).

16. Nevil Payne’s Fatal Jealousy (1673).

17. Nicholas Rowe’s Some Account of the Life of Mr. William Shakespeare (1709).

18. "Of Genius," in The Occasional Paper, Vol. III, No. 10 (1719); and Aaron Hill’s Preface to The Creation (1720).

19. Susanna Centlivre’s The Busie Body (1709).

20. Lewis Theobold’s Preface to The Works of Shakespeare (1734). Spelled “Theobald” in published text.

21. Critical Remarks on Sir Charles Grandison, Clarissa, and Pamela (1754). In preparation.

22. Samuel Johnson’s The Vanity of Human Wishes (1749) and Two Rambler papers (1750).

23. John Dryden’s His Majesties Declaration Defended (1681).

24. Pierre Nicole’s An Essay on True and Apparent Beauty in Which from Settled Principles is Rendered the Grounds for Choosing and Rejecting Epigrams, translated by J. V. Cunningham.

25. Thomas Baker’s The Fine Lady’s Airs (1709).

26. Charles Macklin’s The Man of the World (1792).

27. Out of print.

28. John Evelyn’s An Apologie for the Royal Party (1659); and A Panegyric to Charles the Second (1661).

29. Daniel Defoe’s A Vindication of the Press (1718).

30. Essays on Taste from John Gilbert Cooper’s Letters Concerning Taste, 3rd edition (1757), & John Armstrong’s Miscellanies (1770).

31. Thomas Gray’s An Elegy Wrote in a Country Church Yard (1751); and The Eton College Manuscript.

32. Prefaces to Fiction; Georges de Scudéry’s Preface to Ibrahim (1674), etc.

33. Henry Gally’s A Critical Essay on Characteristic-Writings (1725).

34. Thomas Tyers’ A Biographical Sketch of Dr. Samuel Johnson (1785).

35. James Roswell, Andrew Erskine, and George Dempster. Critical Strictures on the New Tragedy of Elvira, Written by Mr. David Malloch (1763).

36. Joseph Harris’s The City Bride (1696).

37. Thomas Morrison’s A Pindarick Ode on Painting (1767).

38. John Phillips’ A Satyr Against Hypocrites (1655). In preparation.

39. Thomas Warton’s A History of English Poetry. In preparation.

40. Edward Bysshe’s The Art of English Poetry (1708). In preparation.

41. Bernard Mandeville’s "A Letter to Dion" (1732). In preparation.

42. Prefaces to Four Seventeenth-Century Romances. In preparation.

43. John Baillie’s An Essay on the Sublime (1747).

44. Mathias Casimire Sarbiewski’s The Odes of Casimire, Translated by G. Hils (1646).

45. John Robert Scott’s Dissertation on the Progress of the Fine Arts. In preparation.

46. Selections from Seventeenth Century Songbooks.

47. Contemporaries of the Tatler and Spectator.

48. Samuel Richardson’s Introduction to Pamela.

49. Two St. Cecilia’s Day Sermons (1696-1697).

50. Hervey Aston’s A Sermon Before the Sons of the Clergy (1745).

51. Lewis Maidwell’s An Essay upon the Necessity and Excellency of Education (1705).

52. Pappity Stampoy’s A Collection of Scotch Proverbs (1663).

53. Urian Oakes’ The Soveriegn Efficacy of Divine Providence (1682).

54. Mary Davys’ Familiar Letters Betwixt a Gentleman and a Lady (1725).

55. Samuel Say’s An Essay on the Harmony, Variety, and Power of Numbers (1745).

56. Theologia Ruris, sive Schola & Scala Naturae (1686).

57. Henry Fielding’s Shamela (1741).

58. Eighteenth Century Book Illustrations.

59. Samuel Johnson’s Notes to Shakespeare. Vol. I, Comedies, Part I.

60. Samuel Johnson’s Notes to Shakespeare. Vol. I, Comedies, Part II. Combined e-text.

Note D, page image:

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of An Apology For The Study of Northern

Antiquities, by Elizabeth Elstob

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK NORTHERN ANTIQUITIES ***

***** This file should be named 15329-h.htm or 15329-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/1/5/3/2/15329/

Produced by David Starner, Louise Hope and the Online Distributed

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included