Master (after the event). "DO YOU KNOW, YOUNG MAN, THAT THIS PAINS ME MUCH MORE THAN IT DOES YOU?"

The Terror. "NO, I DIDN'T KNOW, SIR. BUT IF THAT ASSERTION GENUINELY EXPRESSES YOUR CONSIDERED OPINION I FEEL VERY MUCH BETTER."

The question as to how America's army will assist the Allies has not yet been decided, so that President WILSON will still be glad of suggestions from our halfpenny morning papers.

The military absentee who said he had just dined at a London restaurant, and therefore did not mind going back to the trenches, acted rightly in not disclosing the name of the restaurant.

The report that M. VENEZELOS was in London has been denied by The Daily Mail and the Press Bureau. It is expected that the news will at once be telegraphed to M. VENEZELOS.

There is a proposal to shorten theatrical performances, and several managers of revue, unable to determine which joke to retain, have in desperation resolved to sacrifice both.

Owing to travelling and other difficulties the British Association have decided not to hold their annual meeting this year. Unofficially, the decision is attributed to the growing prejudice against a continuance of the more frivolous forms of entertainment.

A soldier in Salonika has asked a friend in Surrey to send him some flower seeds for a garden in his camp. We hear that Mr. LYNCH, M.P., is convinced that this is merely an inspired attempt to obscure the real object of the campaign.

We learn with satisfaction that it is proposed to form a Ministry of Health, for many of the Government Departments seem to be suffering from a variety of complaints.

In connection with a recent law case, in which a certain Mr. SHAW was referred to as "one of the public," we hasten to point out that it did not refer to Mr. GEORGE BERNARD SHAW, who, of course, is not in that category.

"Peanuts," says The Daily Chronicle, "do not seem to be receiving the attention they deserve from our food experts." Several of our younger readers who profess to be food experts declare that they are ready to attend to all the peanuts that our contemporary cares to put in their way.

In a duel with revolvers last week two Spanish officers wounded one another. We have all along maintained that duels with revolvers are becoming positively dangerous.

A cheque for twenty-five million dollars has just been handed to M. BRON, Danish Minister at Washington, in payment for the Danish West Indies. This, we understand, includes cost of packing and delivery.

Master (after the event). "DO YOU KNOW, YOUNG MAN, THAT THIS PAINS ME MUCH MORE THAN IT DOES YOU?"

The Terror. "NO, I DIDN'T KNOW, SIR. BUT IF THAT ASSERTION GENUINELY EXPRESSES YOUR CONSIDERED OPINION I FEEL VERY MUCH BETTER."

There is a serious shortage of margarine and many people have been compelled to fall back on butter.

A gossip writer states that one of the recent additions to the Metropolitan Special constabulary weighs seventeen stone. It is not yet decided whether he will take one beat or two.

There is to be no General Election this year for fear that it might clash with the other War.

Another military absentee having told the Thames Police Court magistrate that he did not know there was a War on, it is expected that the Government will have to announce the fact.

It is no longer the fashion to regard the British as a degenerate race. Still it is good to know that one of our rat clubs has killed no fewer than three hundred of these ferocious beasts.

A contemporary suggests that we may yet institute a system of pigeon post, and thus assist the postal services. There will be fine mornings when the exasperated house-holder will be waiting behind the door with a shot-gun for the bird which attempts to deliver the Income Tax papers.

Two litigants in the Bombay High Court have settled their differences by agreeing that the sum in dispute shall be paid into the War Fund. This is considered to be a marked improvement on the old method of dividing it between the lawyers in the case.

"It is my supreme war aim," said Count VON ROON in the Prussian House of Lords, "to keep the Throne and the Dynasty sky high." Once we have knocked them sky high the Count can keep them in any old place he likes.

At a recent concert at Cripplegate Institute in aid of St. Dunstan's Hostel for Blinded Soldiers, lightning sketches of cats by Louis WAIN were sold by auction. The sketching of these night-prowlers by lightning is, we understand, a most exhilarating pursuit, but the opportunities for it are comparatively rare, and most artists have to utilise the moon or the searchlight.

It is announced that owing to the shortage of paper the number of propagandist pamphlets published by the German Government will be diminished. The decision may also have been influenced by the increasing shortage of neutrals.

"Father Waring's boat became jammed while being lowered and hung dangerously, but the ship's surgeon cut the cackles and they descended safely."—The Pioneer (Allahabad)

Another of our strong silent men.

[pg 234]FERDIE.

My nerves are feeling rather bad

About the news from Petrograd.

Briefly, and speaking as a Tsar,

I think the game has gone too far.

When Liberty gets on the wing

You cannot always stop the thing.

Vices from ill examples grow,

And I might be the next to go.

TINO.

Yes, what has happened over there

May very well occur elsewhere.

Fortune with me may prove as fickle as

It did with poor lamented NICHOLAS.

It was a silly thing to do

To ape the airs of WILLIAM TWO;

I cannot think what I was at,

Trying to be an autocrat.

MEHMED.

I take a very dubious tone

About the fate of Allah's Own.

The Young Turk Party's been my bane

And caused me hours and hours of pain;

But, what would be a bitterer pill,

There may be others younger still,

Who, if the facts should get about,

Would want to rise and throw me out.

FERDIE.

I don't believe that WILLIAM cares

One little fig for my affairs.

He roped me in to this concern

Simply to serve his private turn;

And never shed a single tear

Over my loss of Monastir.

For tuppence, if I saw my way,

I'd join the others any day.

TINO.

Last year (its memory still is green) O

How WILLIAM loved his precious TINO!

He talked about our family ties

And sent me such a lot of spies.

But since his foes began to squeeze

My guns inside the Peloponnese

His interest in me has ceased;

I do not like it in the least.

MEHMED.

I lent him troops when things were slack,

And now the beast won't pay 'em back.

He never mentions any "line"

Of HINDENBURG'S in Palestine.

I cannot sleep; I get such frights

During these dark Arabian Nights.

But he—he doesn't care a dem.

O Allah! O Jerusalem!

O.S.

"THE ONE NEW SPRING FASHION.

Every woman who wants the most economical new garment, should buy to-morrow's DAILY SKETCH."—Evening Standard.

It sounds cheap, but would it wear?

SOCIETY "WAR-WORKERS."

DEAREST DAPHNE,—The scarcity of paper isn't altogether an unmixed misfortune, as far as one's correspondence is concerned. Letters that don't matter, letters from the insignificant and the boresome, simply aren't answered. For small spur-of-the-moment notes to one's intimes who're not too far off, there's quite a little feeling for using slates. One writes what one's to say on one's slate (which may be just as dilly a little affair as you please, with plain or chased silver frame, enamelled monogram or coronet, and pencil hanging by a little silver chain), and sends it by a servant. When the note's been read, it's wiped off, the answer written, and the slate brought back. Isn't that fragrant? I may claim to have set this fashion. Of course a very voyant slate is not just-so. The Bullyon-Boundermere woman set up one with a deep, heavily-chased gold frame, and "B.-B." at the top set with big diamonds. C'est bien elle! She'd used it only half-a-dozen times when it was snatched from her footwoman, who was taking it to somebody's house, and hasn't been heard of since!

People Who Matter gave a double-page to illustrating "War-Time Correspondence Slates of Social Leaders." My slate's there, and Stella Clackmannan's, and Beryl's and several more. À propos, have you seen the series of "Well-known War-Workers" they've been having lately in People Who Matter? They're really quite worth while. There's dear Lala Middleshire in one of those charming "Olga" trench coats (khaki face-cloth lined self-coloured satin and with big, lovely, gilt-and-enamelled buttons), high brown boots, and one of those saucy little Belgian caps with a distracting little tassel wagging in front. The pickie is called "The Duchess of Middleshire Takes a War-Worker's Lunch," and dear Lala is shown standing by a table, looking so bravely at two cutlets, a potato, a piece of war bread, a piece of war cheese and a small pudding.

Then there's Hermione Shropshire, in a perfectly haunting lace and taffetas morning robe, with a clock near her (marked with a cross) pointing to eight o'clock! (She lets her maid dress her at that hour now, so that the girl may go and make munitions.) And Edelfleda Saxonbury is shown in an evening gown, wearing her famous pearls. She's leaning her chin on her hand and gazing with a sweet wistful look at an inset view of the hostel where she's washed plates and cups quite several times.

And last but not least there's a pickie that the journalist people have dubbed, "Distinguished Society Women distinguish themselves as Carpenters," et voilà Beryl, Babs and your Blanche, in delicious cream serge overall things, with hammers, planes, and saws embroidered in crewels on the big square collars and turn-up cuffs, and enormously becoming carpenter's caps, looking at a rest-hut we've just finished. Oh, my dearest and best, you don't know what it is to live till you've learned to carpent! It's positively enthralling! When we're skilful enough we're to go abroad—mais il faut se taire! I don't see why we shouldn't go now. We're as skilful as we shall ever be. And even if one or two of our huts had no doors what's that matter? Besides, a hut with no door has a tremendous pull—there wouldn't be any draughts!

Everyone's furious at the way the powers that be have treated Sybil Easthampton. You know what a wonderful thing her Ollyoola Love Dance is. Of course she's lived among the Ollyoolas and knows them in all their moods. (They're natives somewhere ever and ever so far off, where there are palms and coral reefs, and the people don't believe in wrapping themselves up much.) And so she's given the dance at a great many War Fund matinees. That little Mrs. Jimmy Sharpe, daring to criticise it, said there was too much Ollyoola and not enough dance; but everybody who counts simply raves about it. And then, when some manager person offered Sybil big terms to do it at the "Incandescent," he was "officially informed" that, if the Ollyoola Love Dance went into the bill the "Incandescent" would be "placed out of bounds"! What do you, do you think of that, m'amie? A piece of sheer artistry like the Ollyoola Love Dance to be treated so! And it's wonderful not only artistically but scientifically. Each of dear Sybil's amazing wriggles and squirms and crouches and springs is absolutely true—exactly what an Ollyoola does when it's in love.

We're all glad to think we can still see the Ollyoola Love Dance at War Fund matinées.

Ever thine,

BLANCHE.

"A splendid line in corsets, in fine white coutil, usually sold at 14s. 11d., are offered sale at 17s. 11d. each."—Fashions for All.

"BRITISH HARRY THE ENEMY."—Provincial Paper.

And all this time the Germans have been under the impression that it was British Tommy.

[pg 235]

MR. PUNCH. "DO YOU CONTROL FOOD HERE?"

COMMISSIONAIRE. "WELL, SIR, 'CONTROL' IS PERHAPS RATHER A STRONG WORD. BUT WE GIVE HINTS TO HOUSEHOLDERS, AND WE ISSUE 'GRAVE WARNINGS.'"

(Mr. Punch, however, is glad to note that more drastic regulations are about to be enforced.)

LIX.

MY DEAR CHARLES,—Reference the German withdrawal. The matter is proceeding in machine-like order, and one of the first great men to cross No-Man's Land was myself in the noblest of cars. It was, I confess, a purely temporary and fortuitous arrangement which put me in such a conveyance, but I had the feeling that it was excellently fitted to my particular form of greatness, and there were moments when I was so enamoured of it that I was on the verge of getting into a hole with it and staying hid there till the end of the War. Just the right hole was provided at every cross-roads, but the driver wouldn't try them and went round by the fields.

Of the flattened villages and the severed fruit-trees you will have read as much as I have seen. It's a gruesome business, but one charred village is much like another, and the sight is, alas, a familiar one nowadays. For me all else was forgotten in speechless admiration of the French people. Their self-restraint and adaptability are beyond words. These hundreds of honest people, just relieved from the domineering of the Master Swine and restored to their own good France again, were neither hysterical nor exhausted. They were just their happy selves, very pleased about it all, standing in their doorways, strolling about the market-place, watching the march of events as one might watch a play. Every house had its tricolor bravely flying; where they'd got them from so soon I don't know, but no Frenchman ever yet failed, under any circumstances, to produce exactly the right thing at exactly the right moment. There was a nice old Adjoint at the Mairie who wasn't for doing any business at all, with the English or anyone else, until a certain formality had been observed. He had a bottle of old brandy in his cellar, which somehow or other had escaped the German eye these last two years. This, said Monsieur, had first to be disposed of before any other business could conceivably be entertained ... I gathered he had risked much, everything possibly, in keeping this bottle two years; but nothing on earth would induce him to retain it two minutes longer.

Madame, the doctor's wife, approached me as a friend with a request. Would I expedite a letter to her people, to announce her restoration to liberty? I was at Madame's disposal. She handed me the letter. I observed that the envelope was not closed down. Madame's look indicated that this was intentional, and her expression indicated that this was the sort of thing she was used to.

There was no weeping, no extreme emotion. There was a philosophical detachment, a very prevalent humour, and, for the rest, signs of a quiet waiting for "The Day." There is only one day for France, the day of the arrival of Frenchmen on German soil. When the English arrive in Germany there will be nothing doing, except some short and precise orders that we must salute all civilians and pay double for what we buy; but when the French arrive in Germany ... and Heaven send we are going to help them to get well in!

There is a story current, turning on these events, of a young German officer and an official correspondence. It just possibly may be true, since even among such a rotten lot there might conceivably have been one tolerable fellow. The Higher Command had been much intrigued as to a church window, wanting to know (in writing) exactly why and how it had been broken; or rather, as it was the German Higher Command, exactly why and how it had been allowed to remain unbroken. You know how these affairs develop in interest and excitement as the correspondence passes down and down, from one formation to another, and what an air of urgency and bitterness they wear when they reach the last man. In this case the young German subaltern, who had no one else below him on whom to put the burden of explaining in writing, took advantage of his position, and wrote upon a slip, which he attached to the top of the others: "To Officer Commanding British Troops. Passed to you, please, as this town is now in your area...."

Probably the tale isn't true, for if the officer was a German he must have had German blood in him, and if he had German blood in him there couldn't be room for anything else, certainly not for a sense of humour.

We stayed longer than we should have done; this was an occasion upon which one could not insist on the limit of ten handshakes per person. I was delayed also by the Institutrice, who wanted to borrow my uniform, so that she might put it on and so be in a position to start right off at once, paying back. She meant it too, and I should not be surprised to hear that she's been caught doing it by this time. Her mother was there in great form. Asked for her opinion of the dear departed, she said she had already told it to themselves and saw no reason to alter it. "They make war only on women and children; they are lâches." My N.C.O. got out his pocket-dictionary to discover the exact meaning of the word. She told us he needn't trouble; it meant two months' imprisonment. She had a face like a russet apple—a very nice russet apple, too.

We didn't get away before dark, and we found it very hard to discover our way about new country when large hunks of it were missing altogether. One of the party would walk on to find the way, and later I would go forth to find him. We could see the road stretching away in front of us for kilometres; but between us and it there would be twenty yards of nil.

However, the car eventually learnt to stand on its back wheels, climb hedges and make its way home across country, having confirmed its general opinion of the Bosch, that he is only good at one thing, and that is destroying other people's property. I am now back in comfort again, and able to remember your suffering. I send herewith a slice of bully beef (one) and potatoes (two), hoping that they will not be torpedoed, and urging you to hang on, for we are now beginning to think of moving towards Germany, if only to see, when we get there, exactly what the Frenchman has been evolving in his mind all this time.

Yours ever,

HENRY.

"General Ludendorff has received the Red Eagle of the First Class."—Central News.

An appropriate reward for his rapid flight.

[pg 237]

Customer. "LOOK OUT! YOU'RE CONFOUNDEDLY CLUMSY!"

New Assistant. "WELL, YOU CAN'T BE PARTICKLER WHAT YOU DO NOWADAYS. I NEVER WAS A BARBER AFORE, AND I 'ATE AND DESPISE THE JOB—SEE?"

In every home in England you will find their wistful faces,

Where, weary of adventure, lying lonely by the fire,

Untempted by the sunlight and the call of open spaces,

They are listening, listening, listening for the step of their desire.

And, watching, we remember all the tried and never failing,

The good ones and the game ones that have run the years at heel;

Old Scamp that killed the badger single-handed by the railing,

And Fan, the champion ratter, with her fifty off the reel.

The bitches under Ranksboro' with hackles up for slaughter,

The otter hounds on Irfon as they part the alder bowers,

The tufters drawing to their stag above the Horner Water,

The setters on Ben Lomond when the purple heather flowers.

The collie climbing Cheviot to head his hill sheep stringing,

The Dandie digging to his fox among the Lakeside scars,

The Clumber in the marshes when the evening flight is winging

And the wild geese coming over through the rose light and the stars.

And my heart goes out in pity to each faithful one that's fretting

Day by day in cot or castle with his dim eyes on the door.

In his dreams he hunts with sorrow. And for us there's no forgetting

That he helped our love of England and he hardened us for war.

W.H.O.

When MOSES fought with AMALEK in days of long ago,

And slew him for the glory of the Lord,

'Is longest range artill'ry was an arrow and a bow,

And 'is small arms was a barrel-lid and sword;

But to-day 'e would 'ave done 'em in with gas,

Or blowed 'em up with just a mine or so,

Then broken up their ranks by advancing with 'is tanks,

And started 'ome to draw his D.S.O.

When ST. GEORGE 'e went a-ridin' all naked through the lands—

You can see 'im on the back of 'arf-a-quid—

'E spiked the fiery dragon with a spear in both 'is 'ands,

But to-day, if 'e 'd to do what then he did,

'E 'd roll up easy in an armoured car,

'E 'd loose off a little Lewis gun,

Then 'e 'd 'oist the scaly dragon upon a G.S. wagon

And cart 'im 'ome to show the job was done.

Then there weren't no airyplanes and there weren't no bombs and guns;

You just biffed the opposition on the 'ead.

If the world could take all weapons from the British and the 'Uns,

Could scrap the steel, the copper and the lead;

If we fought it out with pick-'andles and fists,

If the good old times would only come agin,

When there weren't no dirty trenches with their rats and lice and stenches,

Why, a month 'ud see us whoopin' through Berlin!

A REPERTORY DRAMA IN ONE ACT.

["A repertory play is one that is unlikely to be repeated."—Old Saying.]

CHARACTERS.

John Bullyum, J.P. (Member of the Town Council of Mudslush).

Mrs. Bullyum (his wife).

Janet (their daughter).

David (their son).

SCENE.—The living-room of a smallish house in the dullest street of a provincial suburb. [N.B.—This merely means that practically any scenery will do, provided the wall-paper is sufficiently hideous. Furnish with the scourings of the property-room—a great convenience for Sunday evening productions.] The room contains rather less than the usual allowance of doors and windows, thus demonstrating a fine contempt for stage traditions. An electric-light, disguised within a mid-Victorian gas-globe, occupies a conspicuous position on one wall. You will see why presently. When the curtain rises Janet, an awkward girl of any age over thirty (and made up to look it) is seated before the fire knitting. Her mother, also knitting, faces her. The appearance of the elder woman contains a very careful suggestion of the nearest this kind of play ever gets to low-comedy.

Janet (glancing at clock on mantelpiece). It's close on nine. David is late again.

Mrs. B. He's aye late these nights. 'Tis the lectures at the Institute that keeps him.

[N.B.—Naturally both women speak with a pronounced accent, South Lancashire if possible. Failing that, anything sufficiently unlike ordinary English will serve.

Janet. He's that anxious to get on, is David.

Mrs. B. Ay, he's fair set on being a town councillor one day, like thy feyther.

Janet (quietly). That 'ud be fine.

Mrs. B. You'd a rare long meeting at the women's guild to-night.

Janet (without emotion). Ay. They've elected me to go to Manchester on the deputation.

Mrs. B. You'll like that.

Janet (suppressing a secret pride so that it is wholly imperceptible by the audience). It'll be well enough. I'm to go first-class. (A pause.) Young Mr. Inkslinger is going too.

Mrs. B. (with interest). Can they spare him from the boot-shop?

Janet. He's left them. He's writing a play.

Mrs. B. (concerned). Dear, dear! And he used to be such a steady young fellow.

[All that matters in their conversation is now finished, but as the play has got to be filled up they continue to talk for some ten minutes longer. At the end of that time—

Janet (glancing at clock again). It's half-past nine, and neither of they men back yet.

[Which means that, while the attention of the audience was diverted, the stage-manager must have twiddled the clock-hands round from behind. This is called realism.

Mrs. B. Listen! Yer feyther's comin' now.

[A door in the far distance is heard to bang. At the same instant John Bullyum enters quickly. He is the typical British parent of repertory; that is to say, he has iron-grey hair, a chin beard, a lie-down collar, and the rest of his appearance is a cross between a gamekeeper and an undertaker.

Bullyum (He is evidently in a state of some excitement; speaks scornfully). Well, here's a fine thing happened.

Mrs. B. What is it, feyther?

Bully, (showing letter). That young puppy, Inkslinger, had the impudence to write me asking for our Janet. But I've told him off to rights. He's nobbut a boot-builder.

Janet (in a level voice). Ye're wrong there, feyther. Bob Inkslinger's a dramatist now.

Bully, (thunderstruck). What?

Janet (as before). He's had a play taken by the Sad Sundays Society.

Bully. Great Powers, a repertory dramatist! And I've insulted him!—me, a town councillor. (He has grown white to the lips; this is not easy, but can be managed.) There'll be a play about me—about us, this house—everything. But (passionately) I'll thwart him yet. Janet, my girl, do thee write at once and say that I withdraw my opposition to the engagement.

Janet (dully). But I don't want the man.

Bully, (hectoring). Am I your feyther or am I not? I tell you you shall marry him. And what's more, he shan't find us what he looks for. No, no (with rising agitation), he thinks that because I'm a town councillor I'm to be made game of, does he? Well, I'll learn him different! (Glaring round) This room—it's got to be changed. And you (to Janet) put on a short frock, something lively and up-to-date—d' ye hear? At once!

Mrs. B. (as Janet only stares without moving). Well, I never.

Bully. And let's have some books about the place—BERNARD SHAW—

Janet (icily). He's a back number now, feyther.

Bully. Well, whoever's the latest. Then you must go to plays and dances, lots of dances. (Struck with an idea) Where's David?

[As he speaks David enters, a tall ungainly youth with spectacles and a projecting brow.

David. Here I yam, feyther.

Bully. It's close on ten. (Hopefully) Have ye been at a night-club?

David. I were kept late at evenin' class.

Bully. Brr! (In an ecstasy of fury) See ye belong to a night-club before the week's out. (He does his glare again.) I'll establish frivolity and a spirit of modernism in this household, if I have to take the stick to every member of it.

Janet (springing up suddenly). Feyther! (A pause; she collects herself for her big effort.) Feyther, I'm one o' they dour silent girls to whom expression comes hardly, but (with veiled menace) when it does come it means fifteen minutes' unrelieved monologue. So tak' heed. We're not wanting these changes, and to be up-to-date, and all that. I'm happy as I am, and so's David. He has his hope of the council, and the bribes and them things. And I've my guild and my friends, with their odd clothes and variable accents. That's the life I want, and I won't change it. I won't—

[Quite suddenly she breaks from them and rushes out of the room, slamming the door after her. The others remain silent, apparently from emotion, but really to see if there will be any applause. When this is settled in the negative old Bullyum speaks again.

Bully, (slowly and as if with an immense effort). Why couldn't she wait?... She might have known we wouldn't decide anything—that we never do decide anything—because it would be too much like a rounded climax. Well (rousing himself), let's put out the gas. [He moves heavily towards the conspicuous bracket.

David (protesting). But, feyther, 'tisn't near time for bed yet.

Bully, (grimly). Maybe; but 'tis more than time play was finished. And this is how.

[He turns the tap. A few moments later the light is switched off with a faintly audible click, and upon a stage in total darkness the curtain falls.[pg 239]

Officer (anxious to pass his recruit who is not shooting well). "DO YOU SMOKE MUCH?"

Recruit. "ABOUT A PACKET OF WOODBINES A DAY, SIR."

Officer. "DO YOU INHALE?" Recruit. "NOT MORE THAN A PINT A DAY, SIR."

My friend, whom for the purpose of concealing his identity I will call Wiggles, opened fire upon me on March 1st (coming in like a lion) with this:

"DEAR WILLIAM,—I have not been well and my doctor thinks it might do me good to come to Cornwall for a few weeks. May I invite myself to stay with you?..."

I accepted his invitation, if I may put it so, and on March 6th received the following:—

"DEAR WILLIAM,—I am not, as I think I said, at all well, and my doctor considers I had better break the journey at Plymouth, as it is a long way from Malvern to Cornwall. Would you recommend me some hotels to choose from? I hope to start by the middle of the month ..."

I recommended hotels, and on the 12th heard from him again:—

"DEAR WILLIAM,—I am very obliged to you. In this severe weather my doctor says that I cannot be too careful, and I doubt if I shall be able to start for ten days or so. Has your house a south aspect, and is it far from the sea? I require air but not wind. And could you tell me ..."

I told him all right, though as a guest I began to think him a little exigeant. But he was unwell.

On the 17th he answered me:—

"DEAR WILLIAM,—I understand you live quite in the country. Would you tell me whether a doctor lives near to you and whether you have a chemist within reasonable distance? My doctor, who really understands my case, won't hear of my starting until the wind changes: but I hope ..."

I drew a map showing my house, the nearest chemist's shop, the doctor's surgery and a few other points of interest, such as Land's End and the Lizard. This I sent to him, and on the 22nd he replied:—

"DEAR WILLIAM,—I acknowledge your map with many thanks. There is one more thing. My doctor insists on a very special diet. Can your cook make porridge? I rely very largely on porridge for breakfast and ..."

I saw myself smiling at Lord DEVONPORT and wired back, "Have you ever known a cook who couldn't make porridge?"

And on the 27th he issued his ultimatum:—

"DEAR WILLIAM,—I have consulted my doctor and he thinks I ought not to tempt Providence by travelling at present, so I have decided to remain in Malvern. I do hope ..."

To this I replied:—

"DEAR WIGGLES,—Holding as you do the old pagan view of Providence, you are quite right not to tempt it. The loss is mine. I hope you will soon be rather less unwell."

Then I went away for three days without leaving an address, and when I returned it was to learn that Wiggles had arrived on the previous evening. And in my study I found him, together with four wires (two to say he wasn't coming and two to say he was) and a table loaded with prescriptions.

He eats enormously.

(Suggested by Mr. SIMONIS' recently published volume.)

O Street of Ink, O Street of Ink,

Where printers and machinsts swink

Amid the buzz and hum and clink;

By night one cannot sleep a wink,

There is no time to stop or think,

One half forgets to eat or drink,

One's brains are knotted in a kink,

One always lives upon the brink

Of "happenings" that strike one pink.

One day the dollars gaily chink,

The next your funds to zero shrink.

And yet I'm such a perfect ninc-

Ompoop I cannot break the link

That binds me to the Street of Ink.

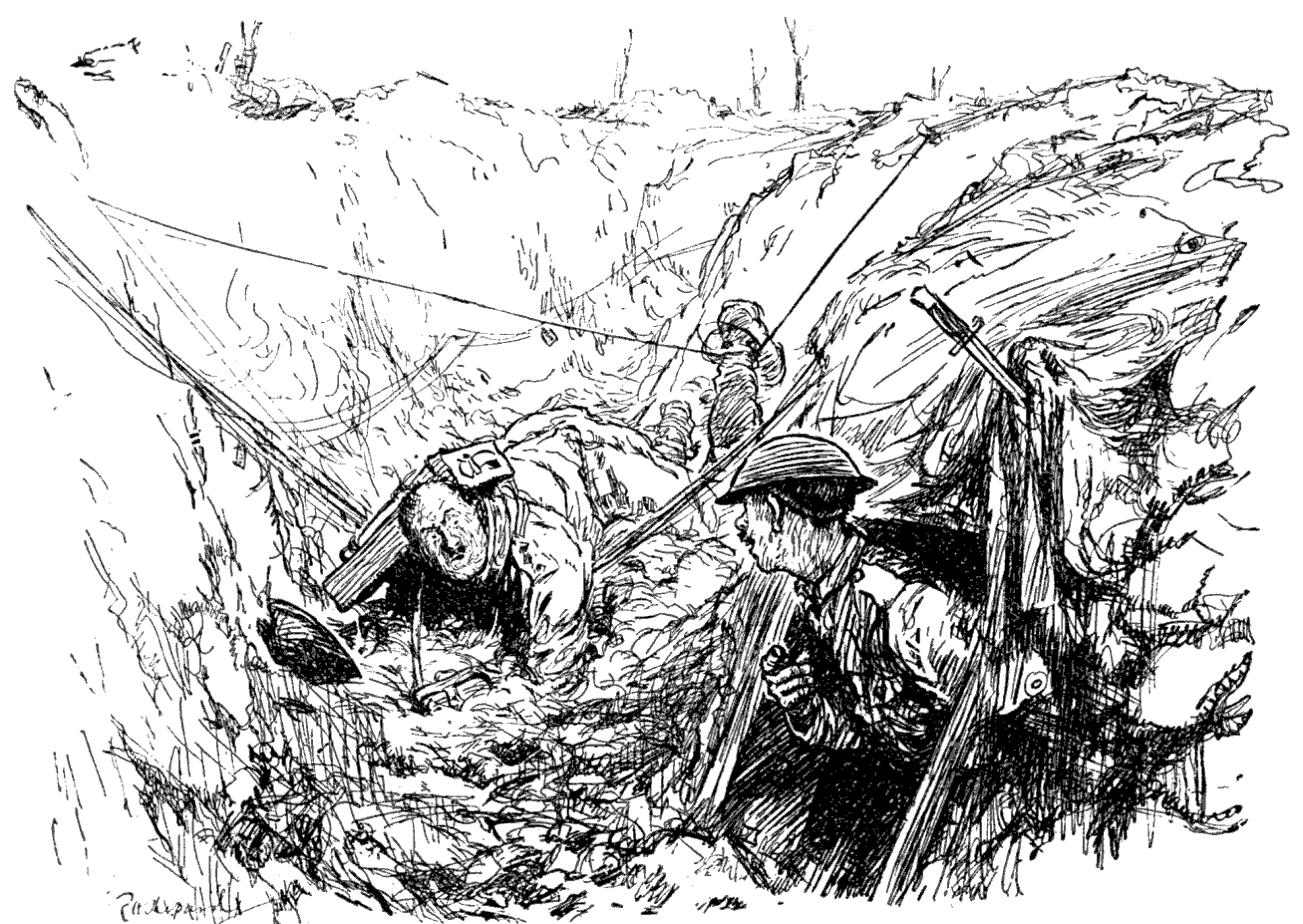

Tommy (to Officer who has only arrived in the trench by accident). "IF YOU'RE A-LOOKIN' FOR THE BURIED CABLE, SIR, IT'S FURTHER ALONG."

VI.

THE CAT AND THE KING.

The cat looked at the King.

She was the boldest cat in the world, but her heart stood still as she vindicated the immemorial right of her race.

What would the King say? What would the King do?

Would he call her up to sit on his royal shoulder? If so, she would purr her loudest to drown the beating of her heart, and she would rub her head against the royal ear. How splendid to be a royal cat!

Or perhaps he would appoint her Mouser to the King's Household, and she would keep the King's peace with tooth and claw.

Or perhaps she would become playmate to the Royal children, and live on cream and sleep all day on a silken cushion.

Or—and this is where her heart ceased to beat—perhaps she would pay the price of her temerity and the Hereditary Executioner would smite off her head.

She had put it boldly to the test, to sink or swim. What would the King do?

The King rose slowly from his throne and passed out to his own apartments, whilst all the Court bowed.

The King had not noticed the cat.

"A Russian official accredited to this country, in an interview with a representative of the Morning Post yesterday, said:—Potatoes."— Evening Times and Echo (Bristol).

"I could well enter into the feelings of this lad's colonel when, with a lint in his eye, he descrihimbed as 'a riceless youngster.'"—Civil and Military Gazette.

We fear that the insertion of the bandage in the colonel's eye must have prevented him from forming a true appreciation of the young fellow.

Headline to a leading article in The Evening News:—

"WATCH ITALY AND RUSSIA."

Extract from same:—

"We ought to keep our eyes fixed on the Western front."

Correspondents should address their inquiries to Carmelite, Squinting House Square.

VI.

ROSEMARY.

Whenas on summer days I see

That sacred herb, the Rosemary,

The which, since once Our Lady threw

Upon its flow'rs her robe of blue,

Has never shown them white again,

But still in blue doth dress them—

Then, oh, then

I think upon old friends and bless them.

And when beside my winter fire

I feel its fragrant leaves suspire,

Hung from my hearth-beam on a hook,

Or laid within a quiet book

There to awake dear ghosts of men

When pages ope that press them—

Then, oh, then

I think upon old friends and bless them.

The gentle Rosemary, I wis,

Is Friendship's herb and Memory's.

Ah, ye whom this small herb of grace

Brings back, yet brings not face to face,

Yea, all who read these lines I pen,

Would ye for truth confess them?

Then, oh, then

Think upon old friends and bless them.

GERMAN SOCIALIST. "I HOLD OUT MY HANDS TO YOU, COMRADE!"

RUSSIAN REVOLUTIONARY. "HOLD THEM UP, AND THEN I MAY TALK TO YOU."

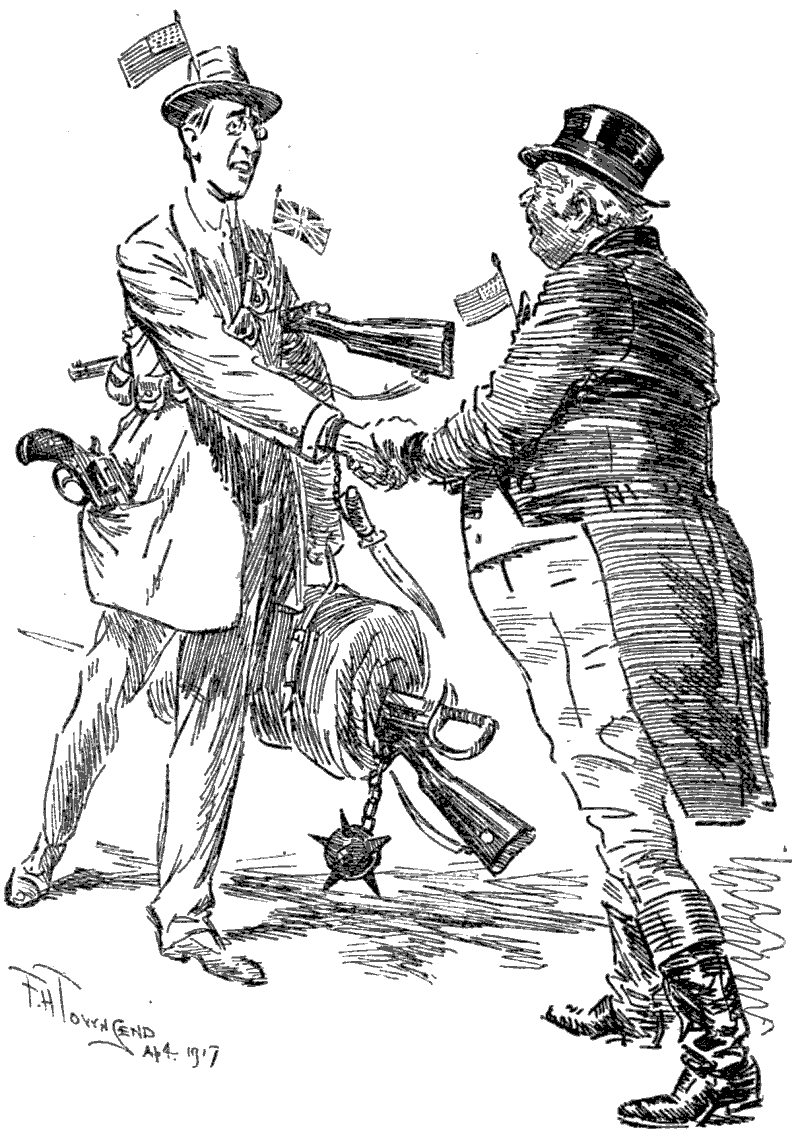

THE UNITED STATES OF GREAT BRITAIN AND AMERICA.

John Bull (to President Wilson). "BRAVO, SIR! DELIGHTED TO HAVE YOU ON OUR SIDE."

Monday, April 2nd.—The MINISTER OF MUNITIONS informed the House that, owing to the demand for explosives, there is a shortage of acid for artificial fertilisers. It is rumoured that Mr. SNOWDEN, Mr. OUTHWAITE and Mr. PRINGLE, feeling that it is up to them to do something useful for their country, have placed at Dr. ADDISON'S disposal a selection from the speeches delivered by them during the War, containing an abundant supply of the necessary commodity.

Mr. JOSEPH MARTIN has all the migratory instincts of his well-known family, and flits from East St. Pancras to British Columbia and back again with engaging irregularity. On his rare visits to Westminster he is always ready to impart in a somewhat strident voice (another family characteristic) the political wisdom that he has garnered from the New World and the Old. But somehow the House fails to take him at his own valuation, and when he tried to belittle the Imperial Conference, on the ground that the Dominion Premier and his colleagues would be much better employed at home, I think there was a general feeling that the physician would be none the worse for a dose of his own prescription.

Cheers greeted little Mr. STEPHEN WALSH as he stepped to the Table to give his first answer as Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of National Service. There were more cheers (in which, had etiquette permitted, the Press Gallery would have liked to join) when it was found that the new Minister needed no megaphone, every word being audible all over the House. And when finally he gave Mr. PRINGLE a much-needed corrective, by telling him that if he wanted further information he must put a Question down, the House cheered again. So far as a single incident enables one to judge, another representative of Labour has "made good."

Viscount VALENTIA has gone to the Lords, and the Commons will henceforth miss the elegant and well-groomed figure which lent distinction to a Treasury Bench not in these days too careful of the Graces. Happily Oxford City has found another distinguished man to succeed him. Mr. J.A.R. MARRIOTT may indeed be said to have obtained a Parliamentary reputation even before, strictly speaking, he was a Member. Usually the taking of the oath is a private affair between the neophyte and the Clerk, and the House hears nothing more than a confused murmur before the ceremony is concluded by the new Member kissing the Book or—more often in these days—adopting the Scottish fashion of holding up the right hand. Oxford's elect would have none of this. Like the Highland chieftain, "she just stude in the middle of ta fluir and swoor at lairge." Not since Mr. BRADLAUGH insisted upon administering the oath to himself has the House been so much stirred; even Members loitering in the Lobby could almost have heard the ringing tones in which Mr. MARRIOTT proclaimed his allegiance to our Sovereign Lord, KING GEORGE THE FIFTH.

Tuesday, April 3rd.—Mr. KING really displays a good deal of ingenuity in his endeavours to get men out of the Army. His latest notion is that all Commanding Officers at home should be ordered to give leave to those men who have gardens so that they may return to cultivate them. There would, no doubt, be a remarkable development of horticultural enthusiasm among our home forces if the War Office were to smile upon the idea; but, though fully alive to the value of food-production, the UNDER-SECRETARY was unable to assent to this wide extension of "agricultural furlough."

A request by the Press Bureau that newspapers would submit for its approval any articles dealing with disputes in the coal-trade gave umbrage to several Members, who saw in it an attempt by the Government to fetter public criticism. Mr. BRACE mildly explained that the object was only to prevent the appearance of inaccurate statements likely to cause friction in an inflammable trade. When Mr. KING still protested, Mr. BRACE again showed that his velvet paw conceals a very serviceable weapon. "Surely the Honourable Member does not believe that inaccurate statements can ever be helpful." Then there was silence.

Mr. BONAR LAW stoutly denied that the National Service scheme was a failure, but admitted that the Cabinet was looking into it with a view to its improvement. Up to the present some 220,000 men have volunteered, but as about half of these are already engaged on work of national importance Mr. NEVILLE CHAMBERLAIN is still a long way short of his hoped-for half-a-million [pg 243] ready, like the British Army, to go anywhere and do anything.

A telegram from the British Ambassador at Washington, stating that President WILSON'S War-speech had been very well received, and that Congress was expected to take his advice, gave great satisfaction. As the MINISTER FOR AGRICULTURE observed, "The outlook for early potatoes may be doubtful, but our SPRING-RICE promises excellently."

Mr. PROTHERO has made up his alleged differences with the SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WAR, and signalized the treaty of peace first by snuggling up to Mr. MACPHERSON on the Treasury Bench, and next by handsomely supporting the new Military Service Bill. In return the UNDER-SECRETARY FOR WAR introduced a much-needed amendment by which men wholly engaged on food-production may be exempted by the Board of Agriculture from the process of "re-combing" now to be applied to the rest of the population.

Wednesday, April 4th.—Mr. SNOWDEN disapproves of the selection of the two Labour Members who are to form part of a deputation about to proceed to Petrograd to convey to the Russian Government the congratulations of the British people. Possibly the neckties of the proposed envoys are not of a sufficiently sanguinary shade, or their brows are not lofty enough to proclaim them true "leaders of thought." The suggestion that the Member for Blackburn should himself be despatched to Petrograd (without a return ticket) has been regretfully abandoned.

Extract from a Canadian lease-form:—

"Will during the said term keep and at its expiration leave the premises in good repair (reasonable wear and tear and accidents by fire or tempest expected)."

"Gentleman single letterarian sportsman 5 linguages tennant pretty little cottage charmingly situated between Montreux Vevey, complete sanitary accommodations vicinity boat, seabaths, golf-grounds excursions receives

PAYING GUEST

moderate terms, Prussians and Austro-Germans, alcoholists undesired."—Swiss Paper.

We do not quite know what a single letterarian is, but he seems to be a person of discriminating taste.

"AVIARIES, POULTRY AND PETS.

Lady ——'s Teeth Society, Ltd.—Gas 2s., teeth at hospital prices, weekly if desired."—Daily Paper.

We are not told under which category Lady ——'s dentures come, but venture to point out that in these days no one should make a pet of them.

(Composed during the recent Spring snowstorm.)

From January's start to close

It rains or hails or sleets or snows.

For atmospherical vagaries

The palm perhaps is February's.

To say March exits like a lamb

Is Falsehood's very grandest slam.

April may smile in Patagonia,

But here it always breeds pneumonia.

May, alternating sun and blizzard,

Plays havoc with the stoutest gizzard.

No part of England is immune

From frost and thunder-storms in June.

Only the suicide lays by

His thickest hose throughout July.

August, in spite of dog-days' heat,

For floods is very hard to beat.

The equinoctial gales, remember,

Are at their worst in mid-September.

Old folk, however hale and sober,

Die very freely in October.

November with its clammy fogs

The bronchial region chokes and clogs.

December, with its dearth of sun,

For sheer discomfort takes the bun.

In the course of a recent search for Italian conversation manuals I came upon one which put so strangely novel a complexion on our own tongue that, though it was not quite what I was seeking, I bought it. To see ourselves as others see us may be a difficult operation, but to hear ourselves as others hear us is by this little book made quite easy. Everyone knows the old story of the Italian who entered an East-bound omnibus in the Strand and asked to be put down at Kay-ahp-see-day. Well, this book should prevent him from doing it again.

But its great attraction is the courageous personality of the protagonist as revealed by his various remarks. For example, most of us who are not linguists confine our conversations in foreign places to the necessities of life, rarely leaving the beaten track of bread and butter, knives and forks, the times of trains, cab fares, the way to the station, the way to the post-office, hotel prices and washing lists. And even then we disdain or flee from syntax. But this conversationalist embroiders and dilates. He is intrepid. He has no reluctances. Where we in Italy would, at the most, say to the cameriere, "Portaci una tazza di caffè," and think ourselves lucky to get it, he lures the London waiter to invite a disquistion on the precious berry. Thus, he begins: "Còffi is ri-marchêbl fòr iz vère stim-iùlêtin pròpèrtê. Du ju nô hau it uòs discòvvard?" The waiter very promptly and properly saying, "Nô, Sôr," the Italian unloads as follows: "Uèl, ai uil tèl ju thèt iz discòvvarê is sêd tu hèv bin òchêsciònt bai thi fòllôin sôrcòmstanz. Som gôts, hu braus-t òp-òn thi plènt fròm huicc thi còffi sîds ar gàthard, uear òbsèrv-d bai thi gôthards tu bi èchsîdingle uêchful, ènd òfn tu chêpar èbaut in thi nait; thi pràior ôv ê nêbarin mònnastere, uiscin tu chip his mònchs êuêch èt thèar mat-tins, traid if thi côffi ud prôdiùs thi sêm èffècht òp-òn thèm, ès it uòs òbsèrv-d tu du òp-òn thi gôts; thi sòch-sès òv his èchspèrimènt lèd tu thi apprèsciêsciòn òv iz valliù."

A little later a London bookseller has the temerity to place some of the latest fiction before our chatty alien, but pays dearly for his rash act. In these words did the Italian let him have it:—"Ai du nòt laich nòv-èls èt òl, bicô-s ê nòv-èl is bàt ê fichtisciòs têl stof-t òv sô mène fantastical dîds ènd nònsènsical wòrds, huicc òpsèt maind ènd hàrt. An-hêppe thô-s an-uêre jòngh pèrsòns, hu spènd thèar prê-sciòs taim in ridin nòv-èls! Thê du nòt nô thèt nòv-èllists, gènnèralle spichin, ar thi laitèst ènd thi môst huim-sical raittars, hu hèv uêstèd ènd uêst thèar laif in liùdnès."

English people abroad do not, as a rule, drop aphorisms by the way; but our Italian loves to do so. Thus, to one stranger (in the section devoted to Virtues and Vices), he remarks, "Uith-aut Riligiòn ui sciùd bi uòrs thèn bîsts." To another, "Thi igotist spîchs còntinniùalle òv himself ènd mêchs himsèlf thi sèntar òv èvvère thingh." And to a third, a little tactlessly perhaps, "Impólait-nès is disgòstin." He is sententious even to his hatter: "Ê hèt sciùd bi prôpôrsciònd tu thi hèd ènd pèrsòn, fòr it is lâf-èbl tu sî ê largg hèt òp-òn ê smòl hèd, ènd ê smòl hèt òp-òn ê largg hèd." But sometimes he goes all astray. He is, for instance, desperately ill-informed as to English law. In England, he tells us, and believes the pathetic fallacy, "thi trêns stàrt ènd arraiv vère pòngh-ciùalle, òthar-uais passèn-giàrs hu arraiv-lêt fòr thèar bis-nès cud siù thi Compane fôr dèm-êgg-s."

He is calm and collected in an emergency. Thus, to a lady who has burst into flames, "Bi not êfrêd, Madam," he says, "thi fair hès còt jur gaun. Lé daun òp-òn thi flòr, ènd ju uil put aut thi fair uith jur hènds." His presence of mind saves him from using his own hands for the purpose. Resourcefulness is indeed as natural to him as to Sir CHRISTOPHER WREN in the famous poem. "Uilliam," he says to his man, "if ènebòde asch-s fòr mi, ju uil sê thèt ai scèl bi bèch in ê fòrt-nait."

He meets Miss Butterfield.

"Mis Bòttarfild," he says, "uil ju ghiv mi ê glàs òv uòtar, if ju plîs?" And that is the end of the lady. Or I think so. But there is just a possibility that it is she (no longer Miss Butterfield, but now a Signora) whom he rebukes in a coffee-house: "Mai diar, du nòt spích òv pòllitichs in ê Còffi-Haus, fòr nò travvellar, if priùdènt, èvvar tòchs èbaut pòllitichs in pòblich." And again it may be for Miss Butterfield that he orders a charming present (first saying it is for a lady): "Ghiv mi thèt ripittar sèt uith rubès, thèt straich-s thi aurs ènd thi hâf-aurs."

Finally he embarks for Australia and quickly becomes as human as the rest of us. "Thi uind," he murmurs uneasily, "is raisin. Thi si is vère ròf. Thi mô-sciòn òv thi Stim-bôt mêch-s mi an-uèl. Ai fîl vère sich. Mai hèd is dizze. Ai hèv gòt ê hèd-êch." But he assures a fellow-passenger that there is no cause for fear, even if a storm should come on. "Du nòt bi àlarmd," he says; "thèar is nô dêngg-ar. Thi Chèp-tèn òv this Stima-r is è vère clèvar mèn."

His last words, addressed apparently to the rest of the passengers as they reach Adelaide, are these: "Lèt òs mêch hêst ènd gô tu thi Còstòm-Haus tu hèv aur lògh-êggs èch-samint. In Òstrêlia, thi Còstòm-Haus Òffisars ar nòt hòtte, bàt vère pôlait."

In our village many disruptions have been wrought by the War, but nothing has ever approached the state of turveydom which came in with the system of daily rations.

Margery brought home the first news of the revolution.

"Most extraordinary thing," she said. "The Joneses have got the two old Miss Singleweeds staying with them."

"What!" I exclaimed, swallowing my ration of mammalia in one astonished gulp. "Why, only two or three days ago Jones told me very privately that the Singleweeds were two of the most interfering, bigoted, cabbage-eating [pg 245] old cats that he had ever come across."

"Cabbage-eating!" repeated Margery thoughtfully. "How stupid we are. That's it, of course."

"What's it?"

"Why, cabbage-eating. The Singleweeds haven't touched meat since I don't know when, so for a consideration of brussels-sprouts and a few digestive biscuits the Joneses will have five pounds of genuine beef to play with."

"Hogs!" I said.

The hospitable influence of the new scheme of rationing spread very rapidly. A few days later we heard that Sir Meesly Goormay, the most self-indulgent and incorrigible egotist in the neighbourhood, had introduced a collection of octogenarian aunts to his household, and, when I was performing my afternoon beat, I was just in time to see the butcher's boy, assisted by the gardener, delivering what looked to be a baron of beef at Sir Meesly's back door. It was an enervating and disgusting spectacle, well calculated to upset the moral of the steadiest special in the local force.

That night at dinner I had a Machiavellian thought.

"Look here," I said, stabbing at a plate of petit pois (1911) and mis-cueing badly, "what about having Uncle Tom to stay for a few weeks?"

"Last time he came," replied Margery, "you said that nothing would induce you to ask him again. You haven't forgotten his chronic dyspepsia, have you?"

"Of course not," I retorted, looking a little pained at such flagrant gaucherie; "but you can't cast off a respectable blood relation because he happens to live on charcoal and hot water."

I delivered an irritable attack on a lentil pudding.

"Right-O," agreed Marjory. "And I'll ask Joan as well. She won't be able to come until Friday, because she's having some teeth extracted on Thursday."

After all Marjory is not altogether without perception.

Dinner over I wrote, in my best style, a short spontaneous invitation to Uncle Tom. Margery wrote a more discursive one to Joan.

"I think we ought to celebrate this," I suggested. "Let's be extravagant."

"All right," said Margery. "What shall it be, champagne or potatoes?"

Two days later I received the following:—

"MY DEAR JAMES,—Thank you very much for your invitation, which I am very pleased to accept. The country, after all, is the proper place for old fogeys like myself, as it is very difficult for them to live up to the present-day bustle of a large city. For the last six months I have been doing odd jobs at a munition factory, which, I must admit, has benefited my health in an extraordinary manner, so much so that I have entirely lost the troublesome dyspepsia I suffered from, and now, you will be glad to hear, I am able to eat like a hunter, as we used to say. Hoping to find you all flourishing on Thursday next, about lunch-time,

"Your affectionate

UNCLE TOM."

Instinctively I took my belt in a hole. Then Margery silently placed this in front of me:—

"DARLING MARGERY,—How perfectly sweet of you! I shall simply love it. I am feeling especially beany as I have just finished with the dentist—usually a hateful person—who found out, after all, that it was not necessary to take out any of my teeth. I adore him. No time for more. Heaps to tell you on Friday,

"Your loving

J.J."

"Hullo! Where are you off to?" I asked, as Margery made for the door.

"Off to? Why, to put our names down on the Singleweeds' waiting list."

I took my belt up another hole and, whistling The Bing Boys out of sheer desperate bravado, made my gloomy way to the potato patch.

Plough Girl. "MABEL, DO GO AND ASK THE FARMER IF WE CAN HAVE A SMALLER HORSE. THIS ONE'S TOO TALL FOR THE SHAFTS."

"Of Swinburne's personal characteristics Mr. Goose, as was to be expected, writes admirably."—Daily News and Leader.[pg 246]

"Francesca," I said, "you must admit that at last I have you at a disadvantage."

"I admit nothing of the sort."

"Well," I said, "have you or have you not got German measles? It seems almost an insult to put such a question to a woman of your energy and brilliant intellectual capacity, but you force me to it."

"Dr. Manley—"

"Come, come, don't fob it off on the Doctor. He didn't wilfully provide you with an absurd attack of this childish disease."

"No, he didn't; but when I was getting along quite nicely with the idea that I was suffering from a passing headache he butted in and sent me to bed as a German measler—and now we've all got it."

"Yes," I said, "you've all got it, all my little chickens and their dam—you're the dam, remember that, Francesca—Muriel's got it, Nina's got it, Alice has got it and Frederick has got it very slightly, but he insists on having all the privileges of the worst kind of invalid; and you've got it, Francesca, and I'm left scatheless in a position of unlimited power and no responsibility."

"Yes," she said, "it's terrible, but you will use your strength mercifully."

"I'm not at all sure about that. At first I felt like one of those old prisoner Johnnies—Baron TRENCK, you know, or LATUDE—who were all shaky and mild when they were at last released; but now I've had time to think—yes, I've had time to think."

"And what is the result of your thoughts?"

"The result," I said, "is that I'm determined to do things thoroughly. I've mastered all your jealously-guarded secrets and I've allowed the strong wind of a man's intellect to blow through them. I am facing the cook on a new system and am dealing with the tradesmen in a spirit of inexorable resolution. The housemaid is being brought to heel and has already begun not to leave her brushes and dust-pans lying about on the floors of the library and the drawing-room. Stern measures are being taken with the kitchen-maid; and Parkins, that ancient servitor, is slowly being reduced to obedience. Even the garden is feeling the new influence and potatoes are being planted where no potatoes were ever planted before. Everything, in fact, is being reformed."

"I warn you," said Francesca, "that your reforms will not be allowed to go on. As soon as I can get rid of the German measles I shall restore everything to its former condition."

"But that," I said, "is the counter-revolution."

"It is; and it's going to begin as soon as I get out of bed."

"And what are you going to bring out of bed with you?"

"Common sense," said Francesca.

"Not at all," I said. "You're going to bring out of bed with you that hard reactionary bureaucratic spirit which all but ruined Russia and is in process of ruining Germany. It will be just as if the TSARITSA got loose and began to have her own way again. By the way, Francesca, what does one do when the butcher says there won't be any haunch of mutton till Tuesday, or when the grocer refuses you your due amount of sugar?"

"A TSARITSA," said Francesca haughtily, "cannot concern herself with sugar or haunches of mutton."

"But suppose that the TSARITSA has got German measles. Couldn't she manage to beat up an interest in mundane affairs?"

"I'll tell you what," said Francesca.

"Do," I said; "I'm dying to hear it."

"Well, you'd better let the strong wind of a man's intellect blow through them."

"What," I said—"through the haunch of mutton?"

"Yes, you could do without the haunch, you know, and score off the butcher."

"That's a sound idea. You're not so badly measled as I thought you were."

"Oh," she said, "I shall soon be rid of them altogether."

"To tell you the truth, I wish you'd hurry up."

"Long live the counter-revolution!"

"Oh, as long as you like," I said.

"Have you given the children their medicine and taken their temperatures?"

"I'm just off to do it," I said.

R.C.L.

SCENE: A lonely road somewhere in France.

Diminutive Warrior (suddenly confronted with ferocious specimen of the local fauna). "LUMME! IF IT AIN'T THE REGIMENTAL COAT-OF-ARMS COME TO LIFE!"

"The Wady Ghuzzeh, or river of Gaza, a stream-bed which makes no large assertion on the map. But it 'just divides the desert from the sewn.'"—Sunday Paper.

Being, as you might say, a mere thread.

Extracts from an article entitled "London Sights: An Australian's Impressions":—

"When all is over and we are back where the coyote cries ... when the Rockies are looking down at us from their snowy heights, and the night-time silence steals across the fir-bordered foothills...."—Sunday Times.

Yet what is all this to the longing of the Canadian for the nightly howl of the kangaroo and the song of the wombat flitting among the blue-gums in his native bush?

According to a French philosopher mankind is divided into two categories, Les Huns et les autres.

"Sydney, January 2.

Concurrently with the inauguration of the new time schedule at 2 a.m. on Monday a violent earth tremor was experienced at Orange. An accompanying noise lasted about a half minute."—Brisbane Courier.

Another family quarrel between Κρονος and Γη.

"Petrograd, Wednesday,

The Council of Workmen's Delegates has issued an appeal to the proletariat, which contains the following striking passage: We shall defend our liberty to the utmost against all attacks within and without. The Russian revolution will not quail before the bayca fwyaa, mfwyawayqawyqa."—Dublin Evening Mail.

If that won't frighten it nothing will.

[pg 247]

"YOU WOULDN'T THINK IT TO LOOK AT 'IM, BUT WHEN I SAYS ''ANDS UP,' 'E ANSWERS BACK IN PUFFICK ENGLISH, 'STEADY ON WITH YER BLINKIN' TOOTHPICK,' 'E SEZ, 'AND I'LL COME QUIET.'"

(By Mr. Punch's Staff of Learned Clerks.)

I am wondering whether, among the myriad by-products of the War, there should be numbered a certain note of virility hitherto (if he will forgive me for saying so) foreign to the literary style of Mr. E. TEMPLE THURSTON. Because I have certainly found Enchantment (UNWIN) a far more vigorous and less saccharine affair than previous experience had led me to expect from him. For which reason I find it far and away my favourite of the stories by this author that I have so far encountered. I certainly think (for example) that not one of his Cities of Beautiful Barley-Sugar contains any figures so alive as those of John Desmond, the hard-drinking Irish squireen, and Mrs. Slattery, his adoring housekeeper. There is red blood in both, and not less in Charles Stuart, a hero whose earlier adventures with smugglers, secret passages and the like have an almost STEVENSONIAN vigour. All the life of impoverished Waterpark, with its wonderful drawing-room full of precarious furniture, is excellently drawn. I willingly allow Mr. THURSTON so much of his earlier manner as is implied in the (quite pleasant) conceit of the fairy-tale. The point is that the real tale here is neither of fairies nor of sugar dolls, but of genuine human beings, vastly entertaining to read about and quite convincingly credible. I can only entreat the author to continue this rationing of sentiment for our mutual benefit.

When a book rejoices in such a title as The Amazing Years (HODDER AND STOUGHTON) and begins with a prosperous English family contemplating their summer holiday in August 1914, you may be tolerably certain beforehand of its subject-matter. When, moreover, the name on the title-page is that of Mr. W. PETT RIDGE, you may with equal security anticipate that, whatever troubles befall this English family by the way, they will eventually reach a happy ending, and find all for the best in the best of all genially humorous worlds. As indeed it proves. But of course the Hilliers were exceptionally fortunate in the fact that when the crash came they had one of those quite invaluable super-domestics whom Mr. PETT RIDGE delights in to steer them back to prosperity. The story tells us how the KAISER compelled the Hilliers to leave "The Croft," and how that very capable woman, Miss Weston, restored it to them again, chiefly by the aid of her antique shop; and to anyone who has recently been a customer in such an establishment this result fully explains itself. I need not further enlarge upon the theme of the book. Your previous knowledge of Mr. PETT RIDGE'S method will enable you to imagine how the various members of the Hillier household confront the changes brought by The Amazing Years; but this will not make you less anxious to read it for yourself in the author's own inimitable telling. I won't call this his best novel; now and again, indeed, there seemed rather too much padding for so slender a plot; but, take it for all in all, and bearing in mind the strange fact that we all love to read about events with which we are already familiar, I can at least promise you a cheery and optimistic entertainment.

Jan Ross, grey-haired at twenty-seven, but sweet of face and of a most taking way, found herself unexpectedly confronted, a year or two ago, with a "job." It was eventually to include the looking after a certain Peter, of the Indian Civil Service, a thoroughly good sort, who by now is making [pg 248] her as happy as she deserves; but in the first place it meant the care of a little motherless niece and nephew and their protection from a scoundrelly father. How successfully she has been doing it and what charmingly human babies are her charges, Tony and Fay, you will realise when I say that it is Mrs. L. ALLEN HARKER who has been telling me all about Jan and Her Job (MURRAY). You will understand, too, how pleasantly peaceful, how utterly removed from the artificially forced crispness of the special correspondent, is the telling of the story; but you must read it yourself to learn how simply and naturally the writer has used the coming of the War for her last chapter, and above all to get to know not only Jan herself but also that most loyal of comrades, her pal Meg. Meg, indeed, is almost as much in the middle of the stage as the friend whose nursemaid she has elected to become; and as the completion of her own private happiness has to remain in doubt until the coming of peace, since Mrs. HARKER has resolutely refused to guarantee the survival of the soldier-sweetheart, you must join me in wishing him the best of good fortune. He is still rubbing it into the Bosches. Perhaps some day the author will be able to reassure us.

When I have said that Twentieth-Century France (CHAPMAN AND HALL) is rather over-weighted by its title my grumble is made. To deal adequately with twentieth-century France in a volume of little more than two hundred amply-margined pages is beyond the powers of Miss M. BETHAM-EDWARDS or of any other writer. But, under any title, whatever she writes about France must be worth reading, and to-day of all times the French need to be explained to us almost as much as we need to be explained to them. Miss BETHAM-EDWARDS can be trusted to do this good work with admirable sympathy and discretion. Here she writes intimately of many people whose names are already household words in France. The more books we have of the kind the better. VOLTAIRE, we are reminded, once said that "when a Frenchman and an Englishman agree upon any subject we may be quite sure they have reason on their side." Well, they are agreeing at present upon a certain subject with what the Huns must regard as considerable unanimity. If in the last century there was any misunderstanding between us and our neighbours it is now in a fair way to be removed to the back of beyond; and in this removal Miss EDWARDS has lent a very helping hand.

What chiefly impressed me about Marshdikes (UNWIN) was what I can only call the blazing indiscretion of the chief characters. To begin with, you have a happily married young couple asking a nice man down for the week-end to meet a girl, and as good as telling him that the party has been arranged, as the advertisements put it, with a view to matrimony. Passing from this, we find a doctor (surely unique) blurting out to a fellow-guest at dinner that a mutual friend had consulted him for heart trouble. To crown all, when the match arranged by the young couple has got as far as an engagement, the wife must needs go and tell the girl that the whole affair was manœuvred by herself. Which naturally upset that apple-cart. It had also the effect of making me a somewhat impatient spectator of the subsequent developments, mainly political, of the plot. I smiled, though, when the hero was worsted in his by-election. After all, with a set of supporters so destitute of elementary tact.... But, of course, I know quite well what is my real grievance. Miss HELEN ASHTON began her story with a chapter so full of sparkle that I am peevish at being disappointed of the comedy that this promised. Perhaps next time she will take the hint, and give us an entire novel in the key which, I am sure, suits her best.

A Little World Apart (LANE) is one of those gentle stories that please as much by reminding you of others like them as by any qualities of their own. Indeed you might call it, with no disparagement intended, a fragrant pot-pourri of many rustic romances—Our Village, for example, and more than a touch of Cranford. Your literary memory may also suggest to you another scene in fiction almost startlingly like the one here, in which the gently-born lover (named Arthur) of the village beauty is forced to combat by her rustic suitor. Fortunately, however, Mr. GEORGE STEVENSON has no tragedy like that of Hetty in store for his Rose. His picture of rural life is more mellow than melodramatic; and his tale reaches a happy end, unchequered by anything more sensational than a mild outbreak of scandal from the local wag-tongues. There are many pleasant, if rather familiar, characters; though I own to a certain sense of repletion arising from the elderly and domineering dowagers of fiction, of whom Lady Crane may be regarded as embodying the common form. A Little World Apart, in short, is no very sensational discovery, but good enough as a quiet corner for repose.

A MODEL

FOR THE HUNS IN BELGIUM.

A MODEL

FOR THE HUNS IN BELGIUM.

NERO MAKES HIMSELF POPULAR ON A FLAG-DAY IN AID OF HOMELESS ROMANS REDUCED TO DESTITUTION BY THE GREAT FIRE.

I do not ask, when back on Blighty's shore

My frozen frame in liberty shall rest,

For pleasure to beguile the hours in store

With long-drawn revel or with antique jest.

I do not ask to probe the tedious pomp

And tinsel splendour of the last Revue;

The Fox-trot's mysteries, the giddy Romp,

And all such folly I would fain eschew.

But, propt on cushions of my long desire,

Deep-buried in the vastest of armchairs,

Let me recline what time the roaring fire

Consumes itself and all my former cares.

I shall not think nor speak, nor laugh nor weep,

But simply sit and sleep and sleep and sleep.

"Wanted, Ladyhelp or General, for country, no bread or butter.—Apply 'Gay,' 'Dominion' Office."—The Dominion (Wellington, N.Z.).

We congratulate the advertiser on her cheery optimism.