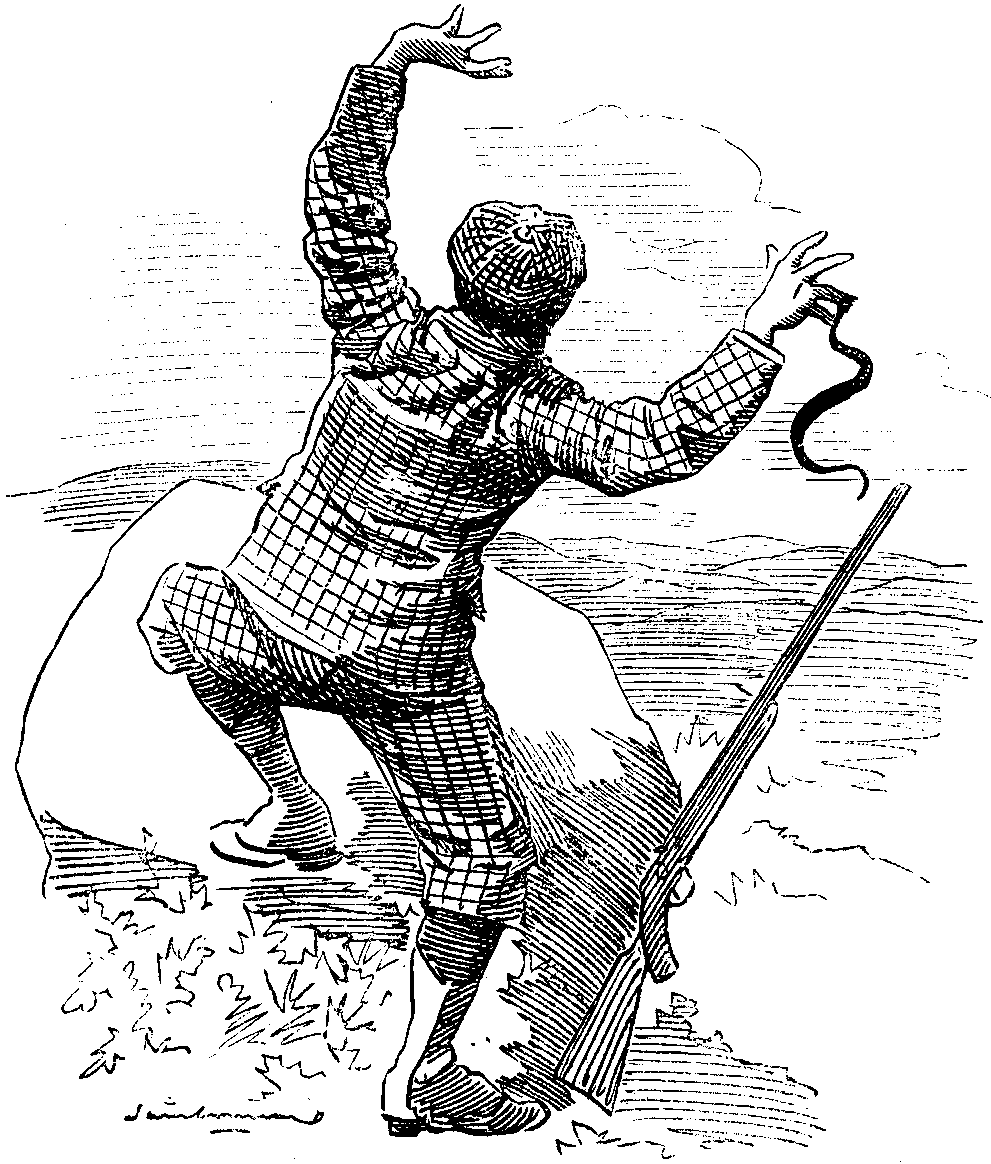

"I had

been bitten by an Adder."

"I had

been bitten by an Adder."

I am in favour of Mr. BRYCE's Access to Mountains Bill, and of Crofters who may be ambitious to cultivate the fertile slopes of all the Bens in Scotland. In fact, I am in favour of anything that will, or may, interfere with the tedious toil of Deer-stalking. Mr. BRYCE's Bill, I am afraid, will do no good. People want Access to Mountains when they cannot get it; when once they can, they will stay where the beer is, and not go padding the wet and weary hoof through peat-hogs, over rocks, and along stupid and fatiguing acclivities, rugged with heather. Oh, preserve me from Deer-stalking; it is a sport of which I cherish only the most sombre memories.

They may laugh, and say it was my own fault, all my misfortune on the stalk, but a feeling reader will admit that I have merely been unlucky. My first adventure, or misadventure if you like, was at Cauldkail Castle, Lord GABERLUNZIE's place, which had been rented by a man who made a fortune in patent corkscrews. The house was pretty nearly empty, as everyone had gone south for the Leger, so it fell to my lot to go out under the orders of the head stalker. He was a man of six foot three, he walked like that giant of iron, TALUS his name was, I think, who used to perambulate the shores of Crete, an early mythical coast-guard. HUGH's step on the mountain was like that of the red deer, and he had an eye like the eagle's of his native wastes.

It was not pleasant, marching beside HUGH, and I was often anxious to sit down and admire the scenery, if he would have let me. I had no rifle of my own, but one was lent me, with all the latest improvements, confound them! Well, we staggered through marshes, under a blinding sun, and clambered up cliffs, and sneaked in the beds of burns, and crawled through bogs on our stomachs. My only intervals of repose were when HUGH lay down on his back, and explored the surrounding regions with his field-glass. Even then I was not allowed to smoke, and while I was baked to a blister with the sun, I was wet through with black peat water. Never a deer could we see, or could HUGH see, rather, for I am short-sighted, and cannot tell a stag from a bracken bush.

At last HUGH, who was crawling some yards ahead, in an uninteresting plain, broken by a few low round hillocks, beckoned to me to come on. I writhed up to him, where he lay on the side of one of those mounds, when he put the rifle in my hand, whispering "Shoot!"

"Shoot what?" said I, for my head was not yet above the crest of the hillock. He only made a gesture, and getting my eye-glass above the level, I saw quite a lot of deer, stags, and hinds, within fifty yards of us. They were interested, apparently, in a party of shepherds, walking on a road which crossed the moor at a distance, and had no thoughts to spare for us. "Which am I to shoot?" I whispered.

"The big one, him between the two hinds to the left." I took deadly aim, my heart beating audibly, like a rusty pump in a dry season. My hands were shaking like aspen leaves, but I got the sight on him, under his shoulder, and pulled the trigger. Nothing happened, I pulled the trigger of the second barrel. Nothing occurred. "Ye have the safety-bolts in," whispered HUGH, and he accommodated that portion of the machinery, which I do not understand. Was all this calculated to set a man at his ease? I took aim afresh, pulled the trigger again. Nothing! "Ye're on half-cock," whispered HUGH, adding some remark in Gaelic, which, of course, I did not understand. Was it my fault? It was not my own rifle, I repeat, and the hammers, at half-cock, looked as high as those of my gun, full-cocked.

All this conversation had aroused the attention of the deer. Off they scuttled at full speed, and I sent a couple of bullets vaguely after them, in the direction of a small forest of horns which went tossing down a glade. I don't think I hit anything, and HUGH, without making any remark, took the rifle and strode off in a new direction. I was nearly dead with fatigue, I was wishing Mr. BRYCE and the British Tourist my share of Access to Mountains, when we reached the crown of a bank above a burn, which commanded a view of an opposite slope. HUGH wriggled up till his eyes were on a level with the crest, and got his long glass out. After some interval of time, he wakened me, to say that if I snored like that, I would not get a shot. Then he showed me, or tried to show me, through the glass, a stag and three hinds, far off to our right. I did not see them, I very seldom see anything that people point out to me, but I thought it wise to humour him, and professed my satisfaction. Was I to shoot at them? No, they were about half a mile off, but, if I waited, they would feed up to us, so we waited, HUGH nudging me at intervals to keep me awake. Meanwhile I was practising aiming at a distant rock, about the place where I expected to get my shot, as HUGH instructed me. I thought the wretched rifle was at half-cock, and I aimed away, very conscientiously, for practice. Presently the rifle went off with a bang, and I saw the dust fly on the stone I had been practising at. It had not been at half-cock, after all; warned by my earlier misfortunes, HUGH had handed the rifle to me cocked. The stag and the hinds were in wild retreat at a considerable distance. I had some difficulty in explaining to HUGH, how this accident had occurred, nor did he seem to share my satisfaction in having hit the stone, at all events.

We began a difficult march homewards, we were about thirteen miles now from Cauldkail Castle. HUGH still, from habit, would sit down and take a view through that glass of his. At last he shut it up, like WELLINGTON at Waterloo, and said, "Maybe ye'll be having a chance yet, Sir." He then began crawling up a slope of heather, I following, like the Prophet's donkey. He reached the top, whence he signalled that there was a shot, and passed the rifle to me, cocked this time. I took it, put my hand down in the heather—felt something cold and slimy, then something astonishingly sharp and painful, and jumped to my feet with a yell! I had been bitten by an adder, that was all! Now, was that my fault? HUGH picked up the rifle, bowled over the stag, and then, with some consideration, applied ammonia to my finger, and made me swallow all the whiskey we had.

It was a long business, and Dr. MACTAVISH, who was brought from a hamlet about thirty miles away, nearly gave me up. My arm was about three feet in circumference, and I was very ill indeed. I have not tried Deer-stalking again; and, as I said, I wish the British Tourist joy of his Access to Mountains.

Once more the North-east wind

Chills all anew,

And tips the redden'd nose

With colder blue;

Makes blackbirds hoarse as crows,

And poets too.

The town with nipping blasts

How wildly blown;

Around my hapless head

Loose tiles are thrown,

Slates, chimney-pots, and lead

Of weight unknown.

My tile and chimney-pot

Flies through the air.

My eyes are full of dust,

My head is bare,

A state of things that must

Soon make me swear!

When thus in early Spring

My joys are few,

I'll warm myself at home

With "Mountain Dew,"

Or fly to Nice, or Rome,

Or Timbuctoo.

Box-Office Keeper at the Imperial Music-Hall (to Farmer Murphy, who is in Town for the Islington Horse Show). "BOX OR TWO STALLS, SIR?"

Murphy. "WHAT THE DEV'L D'YE MANE? D'YE TAKE ME AN' THE MISSUS FOR A PAIR O' PROIZE 'OSSES? OI'LL HAVE TWO SATES IN THE DHRESS CIRCLE, AND LET 'EM BE AS DHRESSY AS POSSIBLE, MOIND!"

The Laureate, seeking Love's last law,

Finds "Nature red in tooth and claw

With ravin"; fierce and ruthless.

But Woman? Bard who so should sing

Of her, the sweet soft-bosomed thing,

Would he tabooed as truthless.

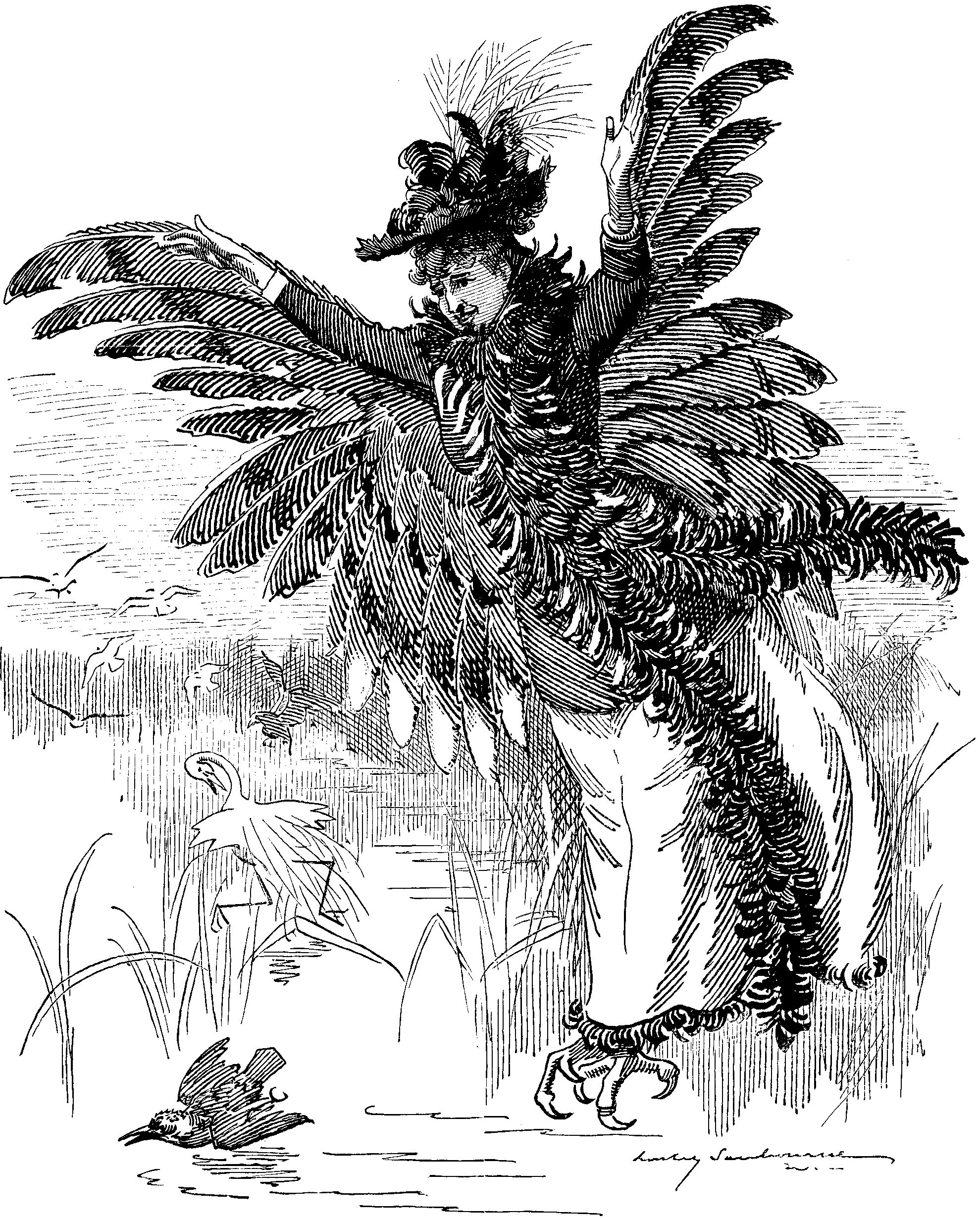

Yet what is this she-creature, plumed

And poised in air? Iris-illumed,

She gleams, in borrowed glory,

A portent of modernity,

Out-marvelling strangest phantasy

That chequered classic story.

Fair-locked and winged. So HESIOD drew

The legendary Harpy crew,

The "Spoilers" of old fable;

Maidens, yet monsters, woman-faced,

With iron hearts that had disgraced

The slaughterer of ABEL.

Chimæra dire! The Sirens three,

Ulysses shunned were such as she,

Though robed in simpler raiment.

Is there no modern Nemesis

To deal out to such ghouls as this

Just destiny's repayment?

O modish Moloch of the air!

The eagle swooping from his lair

On bird-world's lesser creatures,

Is spoiler less intent to slay

Than this unsparing Bird of Prey,

With Woman's form and features.

Woman? We know her slavish thrall

To the strange sway despotical

Of that strong figment, Fashion;

But is there nought in this to move

The being born for grace and love

To shamed rebellious passion?

'Tis a she-shape by Mode arrayed!

The dove that coos in verdant shade,

The lark that shrills in ether,

The humming-bird with jewelled wings,—

Ten thousand tiny songful things

Have lent her plume and feather.

They die in hordes that she may fly,

A glittering horror, through the sky.

Their voices, hushed in anguish,

Find no soft echoes in her ears,

Or the vile trade in pangs and fears

Her whims support would languish.

What cares she that those wings were torn

From shuddering things, of plumage shorn

To make her plumes imposing?

That when—for her—bird-mothers die,

Their broods in long-drawn agony

Their eyes—for her—are closing?

What cares she that the woods, bereft

Of feathered denizens, are left

To swarming insect scourges?

On Woman's heart, when once made hard

By Fashion, Pity's gentlest bard

Love's plea all vainly urges.

A Harpy, she, a Bird of Prey,

Who on her slaughtering skyey way,

Beak-striketh and claw-clutcheth.

But Ladies who own not her sway,

Will you not lift white hands to stay

The shameless slaughter which to-day

Your sex's honour toucheth?

Woman's world's a stage,

And modern women will be ill-cast players;

They'll have new exits and strange entrances,

And one She will play many mannish parts,

And these her Seven Ages. First the infant

"Grinding" and "sapping" in its mother's arms,

And then the pinched High-School girl, with packed satchel,

And worn anæmic face, creeping like cripple

Short-sightedly to school. Then the "free-lover,"

Mouthing out IBSEN, or some cynic ballad

Made against matrimony. Then a spouter,

Full of long words and windy; a wire-puller,

Jealous of office, fond of platform-posing,

Seeking that bubble She-enfranchisement

E'en with abusive mouth. Then County-Councillor,

Her meagre bosom shrunk and harshly lined,

Full of "land-laws" and "unearned increment";

Or playing M.P. part. The sixth age shifts

Into the withered sour She-pantaloon,

With spectacles on nose and "Gamp" at side,

Her azure hose, well-darned, a world too wide

For her shrunk shanks; her once sweet woman's voice,

Verjuiced to Virgin-vinegarishness,

Grates harshly in its sound. Last scene of all,

That ends this strange new-fangled history,

Is sheer unwomanliness, mere sex-negation—

Sans love, sans charm, sans grace, sans everything.

[Despite the laudable endeavours of "The Society for the Protection of Birds," the harpy Fashion appears still, and even increasingly, to make endless holocausts of small fowl for the furnishing forth of "feather trimmings" for the fair sex. We are told that to obtain the delicate and beautiful spiral plume called the "Osprey," the old birds "are killed off in scores, while employed in feeding their young, who are left to starve to death in their nests by hundreds." Their dying cries are described as "heartrending." But they evidently do not rend the hearts of our fashionable ladies, or induce them to rend their much-beplumed garments. Thirty thousand black partridges have been killed in certain Indian provinces in a few days' time to supply the European demand for their skins. One dealer in London is said to have received, as a single consignment, 32,000 dead humming-birds, 80,000 aquatic birds, and 800,000 pairs of wings. We are told too that often "after the birds are shot down, the wings are wrenched off during life, and the mangled bird is left to die slowly of wounds, thirst, and starvation."]

The Gallery is crowded, and there is the peculiar buzz in the air that denotes popular interest and curiosity. The majority of the visitors are of the feminine sex, and appear to have come up from semi-detached villas in the less fashionable suburbs; but there is also a sprinkling of smart and Superior Persons, prosperous City Merchants, who regard pictures with respect, as a paying investment, young Commercial Men, whose feeling for Art is not precisely passionate, but who have turned in to pass the time, and because the Exhibition is gratuitous, earnest Youths with long hair, soft hats, and caped ulsters, &c., &c.

First Villa Resident (appreciatively). Such a death-like expression, isn't it?

Second Ditto, Ditto. Yes, indeed! And how beautifully her halo's done!

Third Ditto, Ditto. Will those two men on the bank be the executioners, should you think?

Fourth Ditto, Ditto (doubtfully). It says in the Catalogue that they're two Christians.

An Intelligent Child. Then why don't they jump in and pull her out, Mother? [The Child is reproved.

A Languid Young Lady. Is that intended for Opheliah?

[The rest regard her with shocked disapproval, mingled with pity, before passing on.

First Matter-of-Fact Person. They're just come back from the funeral, I expect.

Second Ditto, Ditto. I shouldn't wonder. (Feels bound to show that she too can be observant.) Yes, they're all in mourning—even the servant. Do you see the black ribbon in her cap? I do like that.

An Irrelevant Person. It's just a little melancholy, though, don't you think?—which reminds me—how much did you say that jet trimming was a yard—nine pence three-farthings?

Her Friend. Nine pence halfpenny at the shop in St. Paul's Churchyard. The child has her frock open at the top behind, you see—evidently a poor family!

The I.P. Yes, and the workbasket with the reels of cotton and all. (Looking suddenly down.) Don't you call this a handsome carpet?

A Frivolous Frenchman (fresh from 'The Casual Ward' and 'The Martyr' to his companion). Tenez, mon cher, encore des choses gaies!

[He passes on with a shrug.]

A Good Young Man with a train of three Maiden Aunts in tow (halting them before a picture of SIR J. NOEL PATON's). Now you ought to look at this one.

[They inspect it with docility. It represents a Knight in armour riding through a forest and surrounded by seductive Wood-nymphs.

First Maiden Aunt. Is that a guitar one of those girls is playing, or what?

Second Ditto, Ditto. A mandolin more likely; it looks like mother-o'-pearl—is it supposed to be King ARTHUR, and are they fairies or angels, ROBERT?

The G.Y.M. (a little at sea himself). "Oskold and the Ellé-maids," the title is.

Third Aunt. Scolding the Elements! Who's scolding them, ROBERT?

Robert (in her ear). "Oskold and the Ellé-maids!" it's a Scandinavian legend, Aunt TABITHA,

Aunt Tabitha (severely). Then it's a pity they can't find better subjects to paint, in my opinion! (They move on to Mr. PETTIE's "Musician.") Dear me, that young man looks dreadfully poorly, to be sure!

Robert (loudly). He's not poorly, Aunt; he's a Musician—he's supposed to be (quoting from Catalogue) "thinking out a composition, imagining an orchestral effect, with the occasional help of an organ."

First Aunt. I see the organ plain enough—but where's the orchestral effect?

Robert. Well, you wouldn't see that, you know, he only imagines it.

Second Aunt. Oh, yes, I see. Subject to delusions, poor man! I thought he looked as if he wanted someone to look after him.

First Loyal Old Lady (reading from Catalogue). "No. 35. 'Lent by Her Majesty the QUEEN.'"

Second Ditto, Ditto. Lent by HER MAJESTY, my dear! Oh, I don't want to miss that—which is it—where?

[She prepares herself to regard it with a special and reverent interest.

Matter-of-Fact Person (to her Irrelevant Friend). Here's a Millais, you see. Ophelia drowning herself.

The Irrelevant Friend (who doesn't approve of suicide). Yes, dear, very peculiar—but I don't quite like it, I must say. Do you remember whether I told SARAH to put out the fiddle-pattern forks and the best cruetstand before I came away? Dear Mr. HOMERTON is coming in to supper to-night, and I want everything to be nice for him.

The Good Young Man. There's Ophelia again, you see. (Searches for an appropriate remark.) She—ah—evidently understood the art of natation.

First Aunt. She looks almost too comfortable in the water, I think. Her mouth's open, as if she was singing.

Second Aunt (extenuatingly). Yes—but those wild roses are very naturally done—and so are her teeth.

A Discriminating Person. I like it all but the figure.

A Well-informed Person. There's the "Dream of Dante," d'ye see? No mistaking the figure of DANTE. Here he is, down below, having his dream—that's the dream in that cloud—and up above you get the dream done life-size—queer sort of idea, isn't it?

A Ponderous Person (finding himself in front of "The Vale of Rest"). Ha!—what are those two Nuns up to?

His Companion. Digging their own graves, I think.

The Pond. P. (with a supreme mental effort). Oh, Cremation, eh?

[Goes out, conceiving that he has sacrificed at the shrine of Art sufficiently for one afternoon.

Young Discount (to Young TURNOVER—before "Claudio and Isabella"). Something out of SHAKSPEARE here, you see.

Young Turnover. Yairss. (Giving Claudio a perfunctory attention.) Wants his hair raking, don't he? Not much in my line, this sort of subject.

Young Disc. Nor yet mine—takes too much time making it out, y'know. This ain't bad—"Venetian Washerwomen"—is that the way they get up linen over there?

Young Turn. (who has "done" Italy) Pretty much. (By way of excuse for them.) They're very al fresco out in those parts, y' know. Here's a Market-place in Italy, next to it. Yes, that's just like they are. They bring out all those old umbrellas and stalls and baskets twice a-week, and clear 'em all off again next day, so that you'd hardly know they'd been there!

Young Disc. (intelligently). I see. After Yarmouth style.

Young Turn. Well, something that way—only rather different style, y' know.

An Appreciative Lady. Ah! yes, it is wonderfully painted! Isn't it lovely the way that figured silk is done? You can hardly tell it isn't real, and the plush coat he's wearing; such an exquisite shade of violet, and the ivy-leaves, and the nasturtiums and the old red [pg 233] brick; yes, it's very beautiful—and yet, do you know, (meditatively) I almost think it's prettier in the engravings!

A Fiancé. This is the "Wheel of Fortune," EMILY, you see. (Reads.) "Sad, but inexorable, the fateful figure turns the wheel. The sceptred King, once uppermost, is now beneath his Slave ... while beneath the King is seen the laurelled head of the Poet."

His Fiancée (who would be charming if she would not try—against Nature—to be funny.) It's a kind of giddy-go-round then, I suppose; or is it BURNE-JONES's idea of a revolution—don't you see—revolving?

Fiancé (who makes a practice—even already—of discouraging these sallies.) It's only an allegorical way of representing that the Slave's turn has come to triumph.

Fiancée. Well, I don't see that he has much to triumph about—he's tied on like the rest of them, and it must be just as uncomfortable on the top of that wheel as the bottom.

[Her Fiancé recognises that allegory is thrown away upon her, and proposes to take her into the Hall and show her Gog and Magog.

A Niece (to an Impenetrable Relative—whom she plants, like a heavy piece of ordnance, in front of a particular canvas). There, Aunt, what do you think of that now?

The Aunt (after solemnly staring at it with a conscientious effort to take it in.) Well, my dear, I must say it—it's very 'ighly varnished. [She is taken home as hopeless.

A splendid hand is just now held by Mr. ARTHUR CHUDLEIGH, Sole Lessee and Manager of the Court Theatre. Full of trumps, honours and odd tricks. A perfect entertainment in three pieces. You pay your money and you take your choice. You can come in at 8:15 and see The New Sub, by SEYMOUR HICKS (Brayvo, 'ICKS! and may your success be Hickstraordinary!) or at 9:15 for W.S. GILBERT's Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, or at 10 for A Pantomime Rehearsal, which, as I remarked long ago on seeing it for the first time, might last for ever if only judiciously refreshed, say once in every three months, and on this plan it might continue until it should be played in 1992 by the great-great-grandchildren of the members of the present company.

There is one charming line in the bill—a bill which, on account of its colour, must be "taken as red"—not to be missed by visitors. It comes immediately after the cast of The New Sub; it is this,—"The Uniforms by Messrs. Nathan, Coventry Street." It has a line all to itself, which is, most appropriately, "a thin red line." Now the officers in the programme are given as belonging to the "——shire Regiment" i.e., Blankshire Regiment, but as they are all wearing the Nathan uniform, why not describe them as officers of the Nathanshire Regiment? Perhaps such a title might be more suggestive of Sheriff's Officers than of those belonging to Her Majesty's Army; yet, as these gallant Dramatis Personæ are avowedly wearing NATHAN's uniform (which may they never, never disgrace!) why should they not bear the proud title of "The First Royal Coventry Street Costumiers"? Let those most concerned see to it: our advice is gratis, and, at that price, valuable.

9:15. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. Excellent piece of genuine fun. If Mr. W.S. GILBERT could be induced to add to it, I am sure it would stand an extension of ten minutes to allow Hamlet to return and have a grand combat with the King, and then for all the characters to be poisoned by mistake, and so to end happily.

To everyone who does not look upon SHAKSPEARE's work as "Holy Writ," the question must have occurred, why did the Divine WILLIAMS put his excellent rules and regulations for play-actors into the mouth of a noble amateur addressing distinguished members of "the Profession"? Imagine some royal or noble personage telling HENRY IRVING how to play Cardinal Wolsey, or instructing Sir FREDERICK LEIGHTON in painting, or telling J.L. TOOLE how to "get his laughs"! Probably actor and artist would listen in courtier-like silence to the illustrious lecturer, just as SHAKSPEARE makes his players behave when Hamlet is favouring them with his views on the histrionic art. In Mr. GILBERT's skit the leading Player makes a neat retort, and completely shuts up Hamlet,—who, being mad, deserves to be "shut up,"—much to the delight of King and Court. But, the question remains, why did SHAKSPEARE ever put this speech to the players in Hamlet's mouth? My theory is, that he did not want BURBAGE to play the part, but couldn't help himself, and so, out of pure revenge, he introduced this speech in which he makes BURBAGE himself condemn all his own faults. Later on the Queen describes Hamlet as "fat and scant of breath," which certainly was not the author's ideal Prince of Denmark; and this is evidently interpolated as "a nasty one" for BURBAGE. At the Court Theatre the skit is capitally played all round, though I confess I should have preferred seeing Hamlet made up as a sort of fat and flabby Chadband puffing and wheezing,—an expression, by the way, that suggests another excellent performer in this part, namely, Mr. HERMANN WHEEZIN', who might be induced to appear after a lot of "puffin'."

An Awful

Moment of Suspense. Mlles. May, Christine, Ellaline,

and Decima implore Lord Arthur Grossnez not to throw

up the part. He cannot refuse them; il n'ose

pas.

An Awful

Moment of Suspense. Mlles. May, Christine, Ellaline,

and Decima implore Lord Arthur Grossnez not to throw

up the part. He cannot refuse them; il n'ose

pas.

Finally, A Pantomime Rehearsal is still about the very funniest thing to be seen in any London Theatre at the present time. The ladies are, all of them, as the old gentleman in Pink Dominoes used to say, "Pretty dears!" They dance charmingly, especially Miss ELLALINE TERRISS and Miss DECIMA MOORE, whose two duets and character-dances are things of joy for ever. The representative of Jack Deedes, Barrister-at-Law and Gifted Author, is LITTLE and good, and the services of Mr. DRAYCOTT as the Lime-Light Comedian are invaluable. WEEDON GROSSMITH and BRANDON THOMAS are better than ever: their duet is immense, but their combat is too short. Why not introduce a Corsican Brothers duel? The music, by Mr. EDWARD JONES, is thoroughly appropriate and very catching. By the way, one of the songs most encored goes with the exquisitely sensible and touching refrain of "Diddle doddle diddle chip chop cho choorial li lay," which was enormously popular about thirty years ago when it was sung at EVANS's by SAM COWELL, and by CHARLES YOUNG as Dido on the stage of the St. James's Theatre. Odd this! The air has been a bit altered, but I thought that comic songs once out of date were dead and done for. The success of this is proof to the contrary. Will "Ta-ra-ra-boom" achieve a second success in 1922? Perhaps. A capital entertainment, which has caught on at the Court, says

She. "NO, DON'T SIT THERE, MR. SPLOSHER—THAT'S MY UGLY SIDE!"

He (wishing to please). "WELL—A—REALLY—I DON'T SEE ANY DIFFERENCE!"

SCENE—The G.O.M.'s front door. Two expectant callers, EIGHT-HOURS BILL and Miss SARAH SUFFRAGE, in sore disappointment and some disgust, interlocute:—

Mr. Bill (sardonically). You too? Ah! he ain't no respecter of pussons, he ain't!

Miss Sarah (tartly). Well, this tries the temper of even a Suffrage she-saint.

I did think,—but there, you cannot trust Men—even Grand Old Ones!

Mr. Bill. Trust? Them as do trust Party Leaders are gen'rally sold ones.

It don't a mite matter which side.

Miss Sarah. Well, as far as I see,

The other side shows the most signs, BILL, of favouring Me!

I'm sure Mister BALFOUR was awfully civil and nice.

Mr. Bill. You won't trust Prince ARTHUR too far, if you'll take my advice.

Miss Sarah. Well, no,—but I should like to pay out—the other. Ah, drat him!

I'd comb his scant wool, the old fox, could I only get at him.

I'd pamphlet the wily old word-spinner.

Mr. Bill. Ah! I've no doubt;

But wot can we do when his flunkey assures us he's out?

Miss Sarah. We're out, anyhow.

Mr. Bill. Ah! you see you ain't never got in.

But me, his old pardner and pal! It's a shame, and a sin!

He's throwed lots of cold water of late. I am blowed if I likes

His wobbleyfied views about Payment of Members, and Strikes.

And then that HOOD bizness! Long rigmarole—cheered by the Tories!

I fear it's all Ikybod now with our G.O.M.'s glories.

Miss Suffrage. I never quite liked him—at heart. Mrs. FAWCETT, she warned me.

Mr. Bill. Well, now, I did love him! You see, he so buttered and yarned me;

And now—he won't see me! O WILLYUM, I carn't understand it.

Miss Suffrage. I've asked him politely this time. P'raps next time I'll demand it.

Unsex me? Aha! I am willing to wager Stonehenge

To a pebble, when canvassing's wanted, I'll have my revenge!

Mr. Bill. And though he seems cocksure the Gen'l Election he'll win,

Maybe if he's out to me always, he may not get in! [Exeunt.

Grand Old Voice (within). Look nasty! Now have I done wisely this time—on reflection?

One must be so careful—"in view of the General Election!"

[Mr. MONTAGU WILLIAMS, Q.C., is about to publish, in the pages of Household Words, a series of descriptive articles, embodying his more than Wellerishly "extensive and peculiar" knowledge of London, and entitled "Round London, Down East, Up West."]

When the breeze of romance in my youth blew free,

"A Welcome Guest" I was wont to see.

It was a right good time with me,

A joyful, book-devouring time.

Far about London I was borne,

From night to night, from morn to morn;

From Street to Park, from Tower to Dock.

I was conveyed "Twice Round the Clock."

True Sala-ite was I and sworn,

For it was in the golden prime

Of graphic GEORGE AUGUSTUS:

And now I find me revelling through

A magazine of saffron hue,

Called "Sala's Journal," and I swim

Once more in London's rushing tide,

Piloted as of old by him

Through "London Up to Date." With pride,

I own I have a goodly time,

For still it seems the golden prime

Of graphic GEORGE AUGUSTUS.

But many another since my youth

The streets of Babylon hath trod,

With a statistic measuring-rod,

Or philanthropic gauge. In sooth

There was GEORGE SIMS, there is CHARLES BOOTH.

We now search out the Social Truth;

A goodly plan, in the old time

Foreshadowed in the golden prime

Of worthy HENRY MAYHEW.

Now London Labour, London Poor,

Occupy pen and pencil more

Than Pictures in the Passing Show

Of the Immense Metropolis.

And few have knowledge such as his,

(The great Q.C., the worthy Beak!)

Of modern Babylon, high and low;

And so shall I with interest seek

These pages, full of interest,

"Round London, Down East, and Up West."

True picture of the present time,

Drawn for us by the pencil prime

Of good MONTAGU WILLIAMS!

MISS SARAH SUFFRAGE (indignantly). "OH! 'OUT' IS HE!"

EIGHT-HOURS BILL (angrily). "YUS!—AND HE WON'T GET 'IN,' IF I CAN, HELP IT!!"

[Mr. GLADSTONE has lately published an unsympathetic Pamphlet on "Female Suffrage," and has declined to receive a Deputation on the "Eight Hours Day" question.]

My Lady (to her pet protégée). "PRAY WHOM DID YOUR HUSBAND VOTE FOR?"

Martha Stubbs. "I DON'T KNOW, MY LADY."

My Lady. "BUT SURELY YOUR HUSBAND TOLD YOU?"

Martha Stubbs. "HE DOESN'T KNOW HIMSELF, MY LADY. HE'S SUCH A POOR IGNORANT CREATURE!"

["How many of you men would contribute to a Working Men's Fund the shilling you put on Orme, who, by the way, I am sorry to see was not poisoned to death."—Mr. John Burns in the Park.]

Look 'ere, JOHN, you stow it; you're nuts on the spoutin';

I don't mind a man as can 'oller a bit;

And if shillings are goin', I'd back you for shoutin',

Though your game's an Aunt Sally, all miss and no 'it.

But the blusterin' chap as keeps naggin' the boys on

To fight and get beat all for nothing's an ass.

And I'm certain o' this, that the wust kind o' poison

Is the stuff as you fellers 'ave lots of—that's gas!

What's Orme done to you? 'E can't 'elp a cove bettin'.

To get at 'im for that is a trifle too warm.

And poisonin' racers ain't my kind o' vettin'.

I likes a good 'orse, so 'ere's 'ealth to old Orme.

Take a bolus yourself, it might stop you from roarin';

There's nothin' like tryin' these games on yourself!

And I'll throw BENNY TILLETT and one or two more in,

Just to lay the whole lot o' you up on the shelf.

BEN TILLETT talks big of a mind that's a sewer;

Well, 'e knows what it is, for I'll lay 'e's bin there.

And you'd make a 'orse into cat'smeat on skewer.

My eye, but just ain't you a nice-spoken pair!

I ain't goin' to foller you two like a shadder,

Your 'eads is a darned sight too swelled up with brag.

If you don't want to bust and go pop like a bladder,

Why you'd best take my tip—put 'em both in a bag.

So ta-ta, JOHN. I ain't the least wish to offend you,

But plain words to fellers like you is the best.

If they'd give me my way, why I'd jolly soon end you,

Beard, blather and all; you're no more than a pest.

I can fight and take knocks, and I'll stand by my folk, Sir,

I'll 'elp them as 'elps me with whatever I earns;

But I've this for your pipe, if you're wantin' a smoke, Sir,—

I ain't one for poison, nor yet for JOHN BURNS!

"MURDER IN JEST."—Is it not an extraordinary plea on behalf of a person under sentence of death for murder, that, like IBSEN's heroine, "she had never been able to take life in earnest?" Surely it should be added that "when she took somebody else's life she did take it very much in earnest."

Writing of the brilliant Boanerges of the Liberal Party, the Times says:—"Sir WILLIAM is the strongest stimulant known to the Gladstonian wire-pullers, and his appearance is always an indication that the vital energies of the patient are low. It is well understood that his proper place is by his own fireside, and that his true function is to evolve epigrams and construct original systems of finance in that calm retreat.... But whenever they feel particularly downcast and unhappy, they break in upon his fecund meditations, and get him to fire off a roystering speech."

This affectionate and admiring tribute from the Thunderer to its old favourite contributor "HISTORICUS," is worthy of celebrating in deathless verse. How well a dithyramb on the subject would go to a certain popular tune! As thus:—

'Twould serve them right if never I came

From my own fireside again!

The way the "Thunderer" cuts me up

Is vixenish—as vain.

I was born an Opportunist,

In a general sort of way,

But it's really very impertinent

For the Times to grin and say:—

"Get your HARCOURT! Get your HARCOURT!"

Oh! whenever I'm on spout,

You can hear the Tories shout,

"Get your HARCOURT! Get your HARCOURT!

To cheer you when your spirits are down!"

I started in the Buffo line.

When things seem getting slack,

I'm to the front, with lots of go.

My critics may cry "Quack!"

But quacking's not confined to me.

I do extremely well,

And the more "I give them physic," why

The more they squirm and yell—

"Get your HARCOURT! Get your HARCOURT!"

But they know my sparkling spout—

Will help to turn them out.

"Get your HARCOURT! Get your HARCOURT!"

But I'll meet them when their sun goes down.

To play the great "HISTORICUS" part,

I years ago appeared.

The Thunderers stage then knew my art,

But now that pitch is queered!

They swear that I apostatised

To follow W.G.,

And patter about "Parnellite juice,"

And holloa after me—

"Get your HARCOURT! Get your HARCOURT!"

But, with quip, and jibe, and flout,

I completely put them out.

"Get your HARCOURT! Get your HARCOURT!"

But I beat them, and their sun goes down!

They try all sorts of "counters" to

My slogging strokes—in vain.

The "Thunderer" slates me every day,

But still I slog again.

Old W.G. in 'Ninety-Three

May form a Cabinet;

Then his first thought will be of Me,

And all will cry (you bet!)—

"Get your HARCOURT! Get your HARCOURT!

Whoever may stand out,

Malwood's Squire must join, no doubt.

Get your HARCOURT! Get your HARCOURT!"

And I'll mock them when their sun goes down!

O WILLIAM, you have managed to offend.

The Workmen, and the Women, and the Welsh.

Beware, or you'll discover ere the end

That the three W.'s the great one can squelch!

House of Commons. Monday, May 2.—"Would that midnight or Closure would come!" murmured Prince ARTHUR just now, looking wearily up at clock.

It is only eleven; still another hour; hard even for trained nerves. For more than six hours been discussing Scotch Equivalent Grant. CLARK's musical voice has floated through the House by the half hour.

"A bagpipe with bronchitis nothing to it," says FARQUHARSON, curling himself up with delight as he hears sounds that remind him of his mountain home. HUNTER has relentlessly pursued the unhappy LORD-ADVOCATE, and CALDWELL has thoroughly enjoyed himself. His life, it will be remembered, was temporarily blighted by action of ROBERTSON when he was Lord-Advocate. Got up, following CALDWELL in debate, and dismissed a subject in a quarter of an hour's speech without reference to oration hour-and-half long with which CALDWELL had delighted House. Don't remember what the subject was, but never forget CALDWELL's seething indignation, his righteous anger, his withering wrath. ROBERTSON smiled in affected disregard; but very soon after he found it convenient to withdraw from the focus of CALDWELL's eye, and take refuge on the Scotch Bench. As for CALDWELL, he withdrew his support from Ministers, tore up his ticket of membership as a Unionist, and returned to the Gladstonian fold. A tragic story which SCOTT might have worked up into three volumes had he been alive. He is not, but CALDWELL is, and so are we—at least partially after this six hours' talk round rates in Scotland, whether at ten shillings per head or twelve shillings. At half past eleven human nature could stand it no longer; progress reported although there still remained half-an-hour available time.

Business done.—Scotch Members avenged Culloden.

Tuesday.—"Rather a mean thing for MARJORIBANKS to bolt in this way, don't you think?" said CAMPBELL-BANNERMAN, walking out of House when SINCLAIR showed signs of following CALDWELL. "Says he has some County Council meeting in Scotland. Went off by train last night; promised to be back on Thursday. We'll see. When he made that arrangement he thought Scotch Bill would be through to-night; but it won't. Will certainly go over to Thursday. So Master MARJORIBANKS will find himself caught when he comes back. Meanwhile he's escaped to-day and some hours of last night, which is something. As for me, I've stuck to my post, and will very probably die at it. Go in and listen to SINCLAIR, dear boy, following CALDWELL, succeeded by ESSLEMONT. with CLARK in reserve. I think you'll enjoy yourself."

So I did; thoroughly pleasant afternoon from two o'clock to seven. LORD-ADVOCATE visibly growing leaner in body, greyer in face. CAMPBELL-BANNERMAN's usually genial temperament souring, as will be observed from remarks quoted above. J.B. BALFOUR looking in from Edinburgh professes thoroughly to enjoy the business. But then he's fresh to it. Pretty large attendance of Members, but reserve themselves solely for Division. When bell rings three hundred odd come trooping in to follow the Whips into either lobby; then troop forth again. Long JOHN O'CONNOR beams genially down on scene.

"Glad you're having this for a change," he says. "You grumble when we Irish take the floor. Now the Scotch will oblige. Hope you'll like Caledonian and CALDWELL better than Home Rule and Erin G. O'BRIEN."

"Yes, I do," I boldly answered. Only distraught between conflicting charms of CALDWELL and SINCLAIR. There is a cold massivity about SINCLAIR, a pointedness of profile, when he declares "the Nose have it." But there is a loftiness about CALDWELL's tone, a subdued fire in his manner when he is discussing the difference between a rate of ten shillings and one of twelve, a withering indignation for all that is false or truculent (in short, anything connected with the office of Lord-Advocate) that strangely moves the listener. The very mystery of his ordinary bearing weaves a spell of enchantment around him. For days and weeks he will sit silent, watchful, with his eye on the paralysed Scotch Law Officers. Then, suddenly, as in this debate on the Equivalent Grant, he comes to the front, and pours forth an apparently inexhaustible flood of argumentative oratory, delivered with exhilarating animation. "Give me Peebles for pleasure," said the loyal Lowlander home from a fortnight's jaunt in Paris. "Give me CALDWELL for persuasive argument," says PLUNKET, himself a born orator who has missed scarcely five minutes of this two days' debate.

[pg 239] [pg 240]Curious how influence of the hour permeates and dominates everything, even to the distant Lake Ny'yassa. Question asked when House met as to how things were going on there under Commissioner JOHNSTON. No one at all surprised when, in reply, LOWTHER referred to the "two powerful Chiefs, JUMBE and MCPONDA." Should like to hear the views of the last gentleman on the Scotch Equivalent Grant, its application to secondary education in Scotland, and the probable ultimate destination of the £25,000 allotted to parochial boards.

Business done.—More of the Scotch Equivalent Grant.

Wednesday.—May Day passed off quietly enough; but you can't have air charged with electricity, and your back-cellars filled with dynamite, without danger of explosion. Burst to-day in unlooked-for place, in unexpected circumstances. HALDANE brought in Bill providing that ratepayers should share with Duke of WESTMINSTER and other great landowners benefit of unearned increment. Prospect alluring, but debate not exhilarating. House nearly empty; ASQUITH delivering able but not exciting speech in favour of Bill. Just sort of time and circumstances when, in another place, Judge might be expected to fall asleep on Bench. Citizen ROBERT GALNIGAD BONTINE CUNINGHAME GRAHAM, sitting on Bench behind ASQUITH, listening like the rest of us to his well-ordered argument. The Citizen a little tired with Sunday's peregrination. Been walking about all day with stout stick in hand, and blood-red handkerchief in pocket, ready for any emergency. At favourable moment blood-red handkerchief would flash forth, tied on to stick with timely twine, and there's your flag! Republic proclaimed; Citizen GRAHAM first President, under title GALNIGAD I., and before Secretary-of-State MATTHEWS quite knew where he was, he would be viewing the scene from an elevated position pendant in Trafalgar Square.

Chance had not come; GRAHAM still plain Citizen, in House of Commons listening to commonplace proposals about unearned increment. This evidently wouldn't do. Suddenly jumped up; shook fist at back of ASQUITH's unoffending head, and, à propos de bottes, "wanted to know about the swindling companies and their shareholders?"

ASQUITH really hadn't been saying anything about them; turning round beheld Citizen GRAHAM glaring upon him, throwing about his arms as if he were semaphore signalling to the rearguard of Republican Army.

"Order! Order!" cried SPEAKER, sternly.

"Oh, you can suspend me if you like," said Citizen GRAHAM, airily, as if it were no hanging matter. Members angrily joined in cry of "Order! Order!" SPEAKER promptly "named" the Citizen—not with his full list of names, for time was pressing.

"Name away!" roared the Citizen, whom nothing could disconcert. HOME SECRETARY having no fear of the lamppost before his eyes, formally moved that the Citizen be suspended. GRAHAM snapped his fingers at HOME SECRETARY. "Suspend away!" he shouted.

Members looked on aghast. ROWLANDS standing at the Bar, conscious of his hair slowly uplifting. Belonged to the advanced guard himself; but this going little too far. LUBBOCK, sitting near Citizen, strategically attempted to change the conversation. "Did you ever," he said, blandly, "notice how the queen bee, when she is—"

"Oh, you bee ——" said the Citizen, roughly shaking off the gentle Bee-master.

SAM SMITH shudderingly covered his face with his hands. "I'm so afraid," he whispered, "of the old A-dam coming out." And it did, Citizen GRAHAM himself immediately after going out, stopping at the Bar to shuffle through a few steps of the Carmagnole, and trumpet defiance on his blood-red handkerchief.

After this, a mere flash of lightning through the low clouds of a dull afternoon, ASQUITH went on with his speech, debate proceeded as if nothing had happened, and HALDANE's Bill thrown out by 223 Votes against 148. Business done.—Citizen GRAHAM suspended.

Friday.—House met to-day as it did yesterday and day before to discuss Bills and Motions. But all the talk really turns upon date of Dissolution, and what is likely to happen after a General Election. SQUIRE OF MALWOOD serenely confident in the future.

"Yes," I said to him to-night, "it must be a great comfort to you to reflect that when you come into office you will not have to beat about for a programme. You've got your Newcastle platform, and I suppose a Liberal Ministry will stand upon that."

"You remind me, dear TOBY," said the Squire, with a far-away look, "of a story COLERIDGE brought home from his memorable visit to the United States. On his way down to Chicago he went out on the platform of the car to breathe the air and look at the scenery. 'Come off that,' said the Conductor, following him, 'you can't stand on the platform.' 'My good man,' said JOHN DUKE—you know his silver voice and his bland manner—'what is a platform for, if not to stand on?' 'Platforms,' said the Conductor, sententiously, 'are not made to stand on, they are made to get in on.'"

Business done.—Miscellaneous.

Trust me, scribes who fight and jeer,

From yon blue heavens above us bent,

DICKENS and THACKERAY and SCOTT

Smile at the grumbling Yankee gent.

Howe'er it be, it seems to me

A Novel needs but to be good;

Romancer's more than Realist,

And True Love's course than too much "Blood"!

TOO CONSCIENTIOUS.—"As a protest against gambling in connection with Orme," Mr. W. JOHNSTON, M.P., refused to attend a meeting at the Duke of WESTMINSTER's "for the prevention of the demoralisation of the uncivilised heathen races." Does Mr. W.J. include the Derby among the "heathen races" in connection with Orme?

QUITE APPROPRIATE.—"Acorse," says ROBERT, "it's the rite thing as that the Orse Show at Hislington should be honnerd with the pressince of the LORD MARE."

NOTICE.—Rejected Communications or Contributions, whether MS., Printed Matter, Drawings, or Pictures of any description, will in no case be returned, not even when accompanied by a Stamped and Addressed Envelope, Cover, or Wrapper. To this rule there will be no exception.