AUTHOR OF "THE BOBBSEY TWINS SERIES," "THE BUNNY BROWN SERIES," "THE OUTDOOR GIRLS SERIES," ETC.

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS

Made in the United States of America

12mo. Cloth. Illustrated. 50 cents per volume.

THE SIX LITTLE BUNKERS SERIES

SIX LITTLE BUNKERS AT GRANDMA BELL'S

SIX LITTLE BUNKERS AT AUNT JO'S

SIX LITTLE BUNKERS AT COUSIN TOM'S

SIX LITTLE BUNKERS AT GRANDPA FORD'S

SIX LITTLE BUNKERS AT UNCLE FRED'S

THE BOBBSEY TWINS SERIES

THE BOBBSEY TWINS

THE BOBBSEY TWINS IN THE COUNTRY

THE BOBBSEY TWINS AT THE SEASHORE

THE BOBBSEY TWINS AT SCHOOL

THE BOBBSEY TWINS AT SNOW LODGE

THE BOBBSEY TWINS ON A HOUSEBOAT

THE BOBBSEY TWINS AT MEADOW BROOK

THE BOBBSEY TWINS AT HOME

THE BOBBSEY TWINS IN A GREAT CITY

THE BOBBSEY TWINS ON BLUEBERRY ISLAND

THE BOBBSEY TWINS ON THE DEEP BLUE SEA

THE BUNNY BROWN SERIES

BUNNY BROWN AND HIS SISTER SUE

BUNNY BROWN AND HIS SISTER SUE ON GRANDPA'S FARM

BUNNY BROWN AND HIS SISTER SUE PLAYING CIRCUS

BUNNY BROWN AND HIS SISTER SUE AT AUNT LU'S CITY HOME

BUNNY BROWN AND HIS SISTER SUB AT CAMP REST-A-WHILE

BUNNY BROWN AND HIS SISTER SUE IN THE BIG WOODS

BUNNY BROWN AND HIS SISTER SUE ON AN AUTO TOUR

BUNNY BROWN AND HIS SISTER SUE AND THEIR SHETLAND PONY

THE OUTDOOR GIRL SERIES

THE OUTDOOR GIRLS OF DEEPDALE

THE OUTDOOR GIRLS AT RAINBOW LAKE

THE OUTDOOR GIRLS IN A MOTOR CAR

THE OUTDOOR GIRLS IN A WINTER CAMP

THE OUTDOOR GIRLS IN FLORIDA

THE OUTDOOR GIRLS AT OCEAN VIEW

THE OUTDOOR GIRLS ON PINE ISLAND

THE OUTDOOR GIRLS IN ARMY SERVICE

GROSSET & DUNLAP, PUBLISHERS, NEW YORK

Copyright, 1918, by GROSSET & DUNLAP

Six Little Bunkers at Grandma Bell's

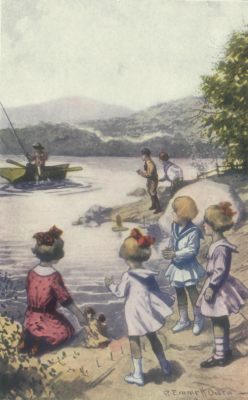

THEY SAW HIM LIFT FROM THE WATER A BIG FISH.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | ALL UPSET | 1 |

| II. | DADDY BUNKER'S WORRY | 11 |

| III. | GRANDMA'S LETTER | 22 |

| IV. | FOURTH OF JULY | 32 |

| V. | THE TRAMP | 42 |

| VI. | MUN BUN'S BALLOON | 52 |

| VII. | LADDIE'S NEW RIDDLE | 63 |

| VIII. | "WHERE IS MARGY?" | 72 |

| IX. | ROSE'S DOLL | 82 |

| X. | THE WRONG DADDY | 92 |

| XI. | THE FUNNY VOICE | 100 |

| XII. | RUSS COULDN'T STOP | 109 |

| XIII. | THE RED-HAIRED MAN | 121 |

| XIV. | THE DOLL'S BUTTONS | 129 |

| XV. | LADDIE'S QUEER RIDE | 139 |

| XVI. | MUN BUN SEES SOMETHING | 150 |

| XVII. | A RED COAT | 160 |

| XVIII. | LADDIE AND THE SUGAR | 170 |

| XIX. | DOWN IN THE WELL | 179 |

| XX. | THE DOG-CART | 190 |

| XXI. | RUSS HEARS NEWS | 197 |

| XXII. | OFF ON A TRIP | 208 |

| XXIII. | THE LUMBERMAN'S CABIN | 216 |

| XXIV. | THE OLD COAT | 226 |

| XXV. | "HURRAY!" | 236 |

THEY SAW HIM LIFT FROM THE WATER A BIG FISH

AND THEN THE FIREWORKS BEGAN

THE RAM WALKED TOWARD MARGY

"BOW-WOW!" BARKED ZIP, AND ON HE RAN, FASTER AND FASTER

"There! It's all done, so I guess we can get on and start off! All aboard! Toot! Toot!" Russ Bunker made a noise like a steamboat whistle. "Get on!" he cried.

"Oh, wait a minute! I forgot to put the broom in the corner," said Rose, his sister. "I was helping mother sweep, and I forgot to put the broom away. Wait for me, Russ! Don't let the boat start without me!"

"I won't," promised the little boy, as he tossed back a lock of dark hair which had straggled down over his eyes. They were dark, too, and, just now, were shining in eagerness as he looked at a queer collection of a barrel, a box, some chairs, a stool and a few boards, piled together in the middle of the playroom floor.

"The steamboat will wait for you, Rose," Russ Bunker went on. "But hurry back," and he began to whistle a merry tune as he moved a footstool over to one side. "That's one of the paddle-wheels," he told his smaller brother Laddie, whose real name was Fillmore, but who was always called Laddie. "That's a paddle-wheel!"

"Why doesn't it go 'round then?" asked Violet, Laddie's twin sister. "Why doesn't it go 'round, Russ? I thought wheels always went around!" Vi, as Violet was usually called, loved to ask questions, and sometimes they were the kind that could not be easily answered. This one seemed to be that kind, for Russ went on whistling and did not reply.

"Why doesn't the footstool go around if it's a wheel?" asked Vi again.

"Oh, 'cause—'cause——" began Russ, holding his head on one side and stopping halfway through his whistled tune. "It doesn't go 'round?"

"Oh, I got a riddle! I got a riddle!" suddenly cried Laddie, who was as fond of asking riddles as Vi was of giving out questions. "What kind of a wheel doesn't go 'round? That's a new riddle! What kind of a wheel doesn't go 'round?"

"All wheels go around," declared Russ, who, now that he had the footstool fixed where he wanted it, had started his whistling again.

"What's the riddle, Laddie?" asked Vi, shaking her curly hair and looking up with her gray eyes at her brother, whose locks were of the same color, though not quite so curly as his twin's.

"There she goes again! Asking more questions!" exclaimed Rose, who had come back from putting away the broom, and was ready to play the steamboat game with her older brother.

"But what is the riddle?" insisted Vi. "I like to guess 'em, Laddie! What is it?"

"What kind of a wheel doesn't go 'round?" asked Laddie again, smiling at his brothers and sisters as though the riddle was a very hard one indeed.

"Pooh! All wheels go around—'ceptin' this one, maybe," said Russ. "And this is only a make-believe wheel. It's the nearest like a steamboat paddle-wheel I could find," and he gave the footstool a little kick. "But all kinds of wheels go around, Laddie."

"No, they don't," exclaimed the little fellow. "That's a riddle! What kind of a wheel doesn't go 'round?"

"Oh, let's give it up," proposed Rose. "Tell us, Laddie, and then we'll get in the make-believe steamboat Russ has made, and we'll have a ride. What kind of a wheel doesn't go around?"

"A wheelbarrow doesn't go 'round!" laughed Laddie.

"Oh, it does so!" cried Rose. "The wheel goes around."

"But the barrow doesn't—that's the part you put things in," went on Laddie. "That doesn't go 'round. You have to push it."

"All right. That's a pretty good riddle," said Russ with a laugh. "Now let's get on the steamboat and we'll have a ride," and he began to whistle a little bit of a new song, something about down on a river where the cotton blossoms grow.

"Where is steamboat?" asked Margy, aged five, whose real name was Margaret, but who, as yet, seemed too little to have all those letters for herself. So she was just called Margy. "Where is steamboat?" she asked. "Is it in the kitchen on the stove?" and she opened wide her dark brown eyes and looked at Russ.

"Oh, you're thinking of a steam teakettle, Margy," he said, as he took hold of her fat, chubby hand. "The teakettle steams on the kitchen stove," went on Russ. "But we're making believe this is a steamboat in here," and he pointed to the barrel, the boxes, the chairs and the footstool, which he and Rose had piled together with such care. For it was a rainy day and the children were having what fun they could in the big playroom.

"I want to go on steamboat," spoke up the sixth member of the Bunker family a moment later.

"Yes, you may have a ride, Mun Bun," said Rose. "You may sit with me in front and see the wheels go around."

Mun Bun, I might say, was the pet name of the youngest member of the family. He was really Munroe Ford Bunker, but it seemed such a big name for such a little chap, that it was nearly always shortened to Mun. And that, added to half his last name, made Mun Bun.

And, really, Munroe Ford Bunker did look a little like a bun—one of the light, golden brown kind, with sugar on top. For Mun, as we shall call him, was small, and had blue eyes and golden hair.

"Come on, Mun Bun!" called Russ, who was the oldest of the family of six little Bunkers, and the leader in all the fun and games. "Come on, everybody! All aboard the steamboat!"

"Oh, wait a minute! Wait a minute!" suddenly called Vi. "Is there any water around your steamboat, Russ?"

"Water? 'Course there is," he answered. "You couldn't make a steamboat go without water."

"Is it deep water?" asked Vi, who seemed started on her favorite game of asking questions.

Russ thought for a minute, looking at the playroom floor.

"'Course it's deep," he answered. "'Bout ten miles deep. What do you ask that for, Vi?"

"'Cause I got to get a bathing-dress for my doll," answered the little girl. "I can't take her on a steamboat where the water is deep lessen I have a bathing-suit for her. Wait a minute. I'll get one," and she ran over to a corner of the room, where she kept her playthings.

"Shall I bring a red dress or a blue one?" Vi turned to ask her sister Rose.

"Oh, bring any one you have and hurry up!" called Russ. "This steamboat won't ever get started. All aboard! Toot! Toot!"

Vi snatched up what she called a bathing-dress from a small trunkful of clothes belonging to her dolls, and ran back to the place where the "steamboat" floated in the "ten-miles-deep water," in the middle of the playroom floor.

"Now I'm all ready, an' so's my doll," said Vi, as she climbed up in one of the chairs behind the big, empty flour barrel that Mother Bunker had let Russ take to make his boat. "Gid-dap, Russ!"

"Gid-dap? What you mean?" asked Russ, stopping his whistling and turning to look at his sister.

"I mean start," answered Vi. "Don't you know what gid-dap means?"

"Sure I know! It's how you talk to a horse. It's what you tell him when you want him to start."

"Well, I'm ready to start now," said Vi, smoothing out her dress, and putting the bathing-suit on her doll.

"Pooh! You don't tell a steamboat to 'gid-dap' when you want that to start!" exclaimed Russ. "You say 'All aboard! Toot! Toot!'"

"All right then. Toot! Toot!" cried Vi, and Margy and Mun, who had climbed up together in a single chair beside Vi, began to laugh.

"I know another riddle," announced Laddie, as he took his place inside the barrel, for he was going to be the fireman, and, of course, they always rode away down inside the steamboat. "I know a nice riddle about a horse," went on Laddie. "What makes a horse's shoes different from ours?" he asked.

"Oh, we haven't time to bother with riddles now, Laddie," said Rose. "You can tell us some other time. We're going to make-believe steamboat a long way across the deep water now."

"A horse's shoes aren't like ours 'cause a horse doesn't wear stockings—that's the answer," went on Laddie.

"All aboard!" cried Russ again.

"All aboard!" repeated Laddie.

"Oh, let's sing!" suddenly said Rose. She was a jolly little girl and had learned many simple songs at school.

"Let's sing about sailing o'er the dark blue sea," went on Rose. "It's an awful nice song, and I know five verses."

"We'll sing it after a while," returned Russ. "We got to get started now. All ready, fireman!" he called to Laddie, who was inside the barrel. "Start the steam going. I'm going to steer the boat," and Russ took his place astride the front end of the barrel, and began twisting on a stick he had stuck down in one of the cracks. The stick, you understand, was the steering-wheel, even if it didn't look like one.

"All aboard! Here we go!" cried Laddie from down inside the barrel, and he began to hiss like steam coming from a pipe. Then he began to rock to and fro, so that the barrel rolled from side to side.

"Here! What're you doing that for?" demanded Russ from up on top. "'You're jiggling me off! Stop it! What're you doing, Laddie?"

"I'm making the steamboat go!" was the answer. "We're out on the rough ocean and the steamboat's got to rock! Look at her rock!" and he swung the barrel to and fro faster than ever.

"Oh! Oh!" cried Rose. "It's all coming apart! Look! Oh, dear! The barrel's all coming apart!"

And that's just what happened! In another moment the barrel on which Russ sat fell apart, and with a clatter and clash of staves he toppled in on Laddie. Then the chairs, behind the barrel, where Rose, Vi and Margy and Mun were sitting, toppled over. In another instant the whole steamboat load of children was all upset in the middle of the playroom floor, having made a crash that sounded throughout the house.

"Dear me! What's that? What happened?" called Mother Bunker from the sitting-room downstairs. "Is any one hurt, children? What did you do?" she asked, as she stood, with some sewing in her hands, at the foot of the stairs, listening for some other noise to follow the crash. She expected to hear crying.

"Is any one hurt?" she asked again. She was somewhat used to noises. One could not live in the house with the six little Bunkers and not hear noises.

"No'm, I guess nobody's hurt," answered Russ, as he climbed out from the wreck of the barrel. "Get up," he added to his brother Laddie.

"I can't," answered Laddie. "My leg's all twisted up in the soap-box." And so it was. A box had been put on one of the chairs, and Mun Bun and Margy had been sitting on that. This box had fallen on Laddie's leg, which was twisted up inside it.

"But what happened?" asked Mother Bunker again. "You really mustn't make so much noise when you play."

"We couldn't help it, Mother," said Rose, who, being the oldest girl, was quite a help around the house, though she was only seven years old. "The steamboat turned over and broke all up, Mother," she went on.

"The steamboat?" repeated Mrs. Bunker.

"I made one out of the flour-barrel you let me take," explained Russ. "But Laddie rocked inside it, and it all fell apart, and then the chairs fell on top of us and Mun and Vi and Margy all fell out and——"

"Oh, my dears! Some of you may be hurt!" cried Mrs. Bunker, as she heard a little sob from Mun Bun. "I must come up and see what it is all about," and, dropping her sewing, up the stairs she hurried.

There were six little Bunkers, as you have probably counted by this time. Six little Bunkers, and they were such a jolly bunch of tots and had such good times, even if a make-believe steamboat did upset now and then, that I'm sure you'll like to hear about them.

To begin with, there was Russ Bunker. Russell was his real name, but he was always called Russ. He was eight years old, and was very fond of "making things."

Next came Rose Bunker. She was only seven years old, but she could do some sweeping and lots of dusting, and was quite a little mother's helper. Rose had light hair and eyes, while Russ was just the opposite, being dark.

Violet, or Vi, aged six, was a curly-haired girl, with gray eyes, and, as I have told you, she could ask more questions than her father and mother could answer.

Then there was Laddie, or Fillmore, a twin of Vi's, and, naturally, of the same age. Just how he happened to be so fond of asking riddles no one knew. Perhaps he caught it from Jerry Simms, who had served ten years in the army, and who never tired of telling about it. Jerry was a not-to-be-mistaken Yankee who worked around the Bunker house—ran the automobile, took out the furnace ashes and, when he wasn't doing something like that, sitting in the kitchen talking to Norah O'Grady, the jolly, good-natured Irish cook, who had been in the Bunker family longer than even Russ could remember.

Jerry was a great one for riddles, too, only he asked such hard ones—such as why does the ginger snap, and what makes the board walk?—that none of the children could answer them.

But I haven't finished telling about the children. After Laddie and Violet came Margy, aged five, and then Mun Bun, the youngest and smallest of the six little Bunkers.

Of course there was Daddy Bunker, whose name was Charles, and who had a real estate office on the main street of Pineville. In his office, Mr. Bunker bought and sold houses for his customers, and also sold lumber, bricks and other things of which houses were built. He was an agent for big firms.

Mother Bunker's name was Amy, and sometimes her husband called her "Amy Bell," for her last name had been Bell before she was married.

The six little Bunkers lived in the city of Pineville, which was on the shore of the Rainbow River in Pennsylvania. The river was called Rainbow because, just before it got to Pineville, it bent, or curved, like a bow. And, of course, being wet, like rain, the best name in the world for such a river was "Rainbow." It was a very beautiful stream.

The Bunker house, a large white one with green shutters, stood back from the main street, and was not quite a mile away from Mr. Bunker's real estate office, so it was not too far even for Mun Bun to walk there with his older sister or brother.

The six little Bunkers had many friends and relatives, and perhaps I had better tell you the names of some of these last, so you will know them as we come to them in the stories.

Mr. Bunker's father had died when he was six years old, and his mother, Mrs. Mary Bunker, had married a man named Ford. She and "Grandpa Ford" lived just outside the City of Tarrington, New York. "Great Hedge Estate" was the name of Grandpa Ford's place, so called because at one side of the house was a great, tall hedge, that had been growing for many years.

Grandma Bell was Mrs. Bunker's mother, and lived at Lake Sagatook, Maine. She was a widow, Grandpa Bell having died some years ago. Margy, or Margaret, had been named for Grandma Bell.

Then there was Aunt Josephine Bunker, or Aunt Jo, Mr. Bunker's sister. She had never married, and now lived in a fine house in the Back Bay section of Boston. Uncle Frederick Bell, who was Mother Bunker's brother, lived with his wife, on Three Star Ranch, just outside Moon City in Montana.

And now, when I have mentioned Cousin Tom Bunker, who had recently been married, and who lived with his wife Ruth at Seaview, on the New Jersey coast, I believe you have met the most important of the relatives of the six little Bunkers. You see they had a grandfather, and two grandmothers, some aunts, an uncle and a cousin. Well supplied with nice relatives, were the six little Bunkers, and thus they had many places to visit.

But I'll tell you about that part later on. Just now we must see what happened after the steamboat broke to pieces because Laddie jiggled himself inside the barrel, when Russ was sitting on the outside of it.

"Are you sure none of you is hurt? You look so!" cried Mother Bunker, as she saw the confused mass of children, barrel staves, box, footstool and chairs in the middle of the playroom floor.

"I'm all right," said Laddie, as he pulled his leg out from where it was doubled up in the box, and stood up straight.

"So'm I," added Russ. "Did I fall on you, Laddie?"

"Yep—but it didn't hurt me much."

"My dear Mun Bun!" said his mother, pulling the little boy out from under a chair. "Are you hurt?"

Munroe Bunker was going to cry, but when he saw that Margy had no tears in her eyes, he made up his mind that he could be as brave as his little sister. So he squeezed back his tears and said:

"I just got a bounce on my head."

"Well, as long as it wasn't a bump you're lucky," said Russ with a laugh.

Vi pulled her doll out from under the pile of barrel staves. The doll's bathing-dress was torn, but Rose said that didn't matter because it was an old one anyhow.

"What made it break?" asked Vi as she did this. "Did somebody hit your steamboat, Russ? Or did it just sink?"

"I guess it sank all right," Russ answered, laughing.

"Well, what made it?" went on Vi.

"Oh, my dear! Don't ask so many questions," begged Mrs. Bunker.

"I got a new riddle," announced Laddie, as he rubbed his leg where it had been a little scratched on a box. "It's a riddle about a wheelbarrow and——"

"You told us that!" interrupted Russ.

"Well, then I can make up another," Laddie went on. He was always ready to do that. "This one is going to be about a barrel. When does a barrel feel hungry?"

"Pooh! There can't be any answer to that!" declared Russ. "A barrel can't ever be hungry."

"Yes it can, too!" cried Laddie. "When a barrel takes a roll, isn't it hungry? A roll is what you eat," he explained, "I didn't think that riddle up," he added, for Laddie was quite honest. "Jerry Simms told me. When is a barrel hungry? When it takes a roll before breakfast—that's the whole answer."

"That's a very good riddle," said Mrs. Bunker with a smile. "But I haven't yet heard what happened."

"Didn't you hear the noise?" asked Rose with a laugh. "It made a terrible bang."

"Oh, yes, I heard that," answered Mrs. Bunker. "But what caused it?" she asked anxiously.

Five little Bunkers looked at Russ, as the one best fitted to tell about the upset.

"We had a make-believe steamboat," explained the oldest boy. "Laddie was inside the flour barrel you let me take. He was the fireman. I sat outside the barrel to steer. But Laddie jiggled and wiggled and joggled inside the barrel and——"

"I had to, Mother, 'cause I was making believe the steamer was on the rough ocean where the water is ten miles deep," interrupted Laddie. "So I rolled the barrel and joggled it and——"

"And then it fell in!" added Rose. "I saw it."

"I felt it," remarked Russ, rubbing his back. "But it didn't hurt me much," he added.

"I guess the barrel was so old and dry that it couldn't hold together when you two boys got to playing with it," said Mrs. Bunker. "Well, I'm glad it was no worse. At first it sounded as though the house was coming down. You had better play some other game now."

"Oh, the rain has stopped!" cried Rose, looking out of a window. "We can play out in the yard now."

"Yes, I believe you can," said her mother. "But you must put on your rubbers, for the ground is damp. Run out and play!"

With shouts of glee and laughter the six little Bunkers started to go outdoors. It was a warm day, late in June, and even the rain had not made it too cool for them to be out.

As the six children trooped out on the side porch they saw their father coming up the walk.

"Why, it isn't supper time, and daddy's coming home!" exclaimed Rose.

"What do you s'pose he wants?" asked Russ.

"Maybe he heard the barrel break and came up to see about it," suggested Laddie.

"He couldn't hear the barrel break away down to his office," said Russ.

Just then Mrs. Bunker, from within the house, saw her husband approaching. She went out on the porch to meet him.

"Why, Charlie!" she exclaimed, "has anything happened? What is the matter? You look worried!"

"I am worried," said Mr. Bunker. "I've had quite a loss! It's some valuable real estate papers. They are gone from my office, and I came to see if they were on my desk in the house. Hello, children!" he called to the six little Bunkers. But even Mun Bun seemed to know that something was wrong. Daddy Bunker's voice was not at all jolly.

His loss was worrying him, his wife well knew.

While the other children, being too young to understand much about Daddy Bunker's worry, ran down to play in the yard, Russ and Rose stayed on the porch with their father and mother. They heard Mrs. Bunker ask:

"What sort of papers were they you lost?

"Well, I don't know that I have exactly lost them," said Mr. Bunker slowly, as though trying to think what really had happened, "I had some real estate papers in my desk at the office. They were about some property I was going to sell for a man, and the papers were valuable. But a little while ago, when I went to look for them, I couldn't find them. It means the loss of considerable money."

"Perhaps they are in your desk here," said Mrs. Bunker, for her husband sometimes did business at his home in the evening, and had a desk in the sitting-room.

"Perhaps they are," said the father of the six little Bunkers. "That is why I came home so early—to look."

He went into the house, followed by his wife and Russ and Rose. Mr. Bunker stepped over to his desk, and began looking through it. He took out quite a bundle of books and papers, but those he wanted did not seem to be there.

"Did you find them?" asked his wife, after a while.

"No," he answered with a shake of his head, "I did not. They aren't here. I'm sorry. I need those papers very much. I may lose a large sum of money if I don't find them. I can't see what could have happened to them. I had them on my desk in the office yesterday, and I was looking at them when Mr. Johnson came along to see about buying some lumber from the pile in the yard next to my office."

"Perhaps Mr. Johnson might know something about the papers," suggested Mrs. Bunker.

Her husband did not answer her for a moment. Then he suddenly clapped his hands together as a new thought came to him, and he said:

"Oh, now I remember! I left those papers in my old coat."

"Your old coat!" repeated Mrs. Bunker with interest.

"Yes. That old ragged one I sometimes wear at the office when I have to get things down from the dusty shelves. I had on that coat when I was holding the papers in my hand, and then Mr. Johnson came along. I wanted to go out in the lumberyard with him, to look at the boards he wanted to buy, so I stuck the papers in the pocket of the old coat."

"Then that's where they must be yet," said Mrs. Bunker. "Where is the coat?"

"Oh, I always keep it hanging up behind the office door. Yes, that's it. I remember now. When Mr. Johnson came in and I went out to look at the lumber with him, I stuck the papers in the inside pocket of the old, ragged coat. And then I forgot all about them until just now, when I had to have them. I'll hurry back to the office and get the papers out of the pocket of the coat."

"May we come with you?" asked Russ.

"Please let us," begged Rose.

Mr. Bunker, who did not seem quite so worried now, looked at his wife.

"Take the children, if you have time," she said. "At least Rose and Russ. The others are playing in the sand," for that's what they were doing. Vi, Laddie, Margy and Mun Bun were digging in a pile of sand at one end of the yard.

"All right, come along, Little Flower, and you, too, Whistler," said Mr. Bunker, giving Russ a pet name he used occasionally.

The two children, delighted to be out after the rain, went down the street with their father, leaving their smaller brothers and sisters playing in the sand. Russ and Rose felt they were too old for this—especially just now.

"Did you hear what happened to us?" asked Russ, as he walked along, holding one of his father's hands, while Rose took the other.

"What happened when?" asked Mr. Bunker.

"When I made a steamboat partly out of a barrel," went on Russ. "It got broken when Laddie was inside it and I was outside. But we didn't any of us get hurt."

"Well, I'm glad of that," said Mr. Bunker with a smile.

"And Laddie made up a funny riddle about the barrel" went on Rose. "Jerry told it to him, though. It's like this—'Why does a barrel eat a roll for breakfast?'"

"Why does a barrel eat a roll for breakfast?" repeated Mr. Bunker. "I didn't know barrels ate rolls. I thought they always took crackers or oatmeal or something like that."

"Oh, she hasn't got it right!" said Russ, with a laugh at his sister. "The riddle is, 'When is a barrel hungry?' and Laddie says Jerry told him it was when the barrel takes a roll before breakfast."

"Oh, I see!" laughed Mr. Bunker. "Well, that's pretty good. Now I have a riddle for you. 'How many lollypops can you buy for two pennies?'" and he stopped in front of a little store with the two children—one on each side of him.

Russ looked at Rose and Rose looked at Russ. Then they smiled and looked at their father.

"I think we can find the answer to that riddle in here," went Mr. Bunker, as he led the way into the candy store, for it was that kind.

And Russ and Rose soon found that they could each get a lollypop for a penny.

"You used to get two for a cent," said Russ. "But I guess, on account of everything being so high, they only give you one."

"Well, one at a time is enough, I should think," said Mr. Bunker, as they went out of the store. "If you had two lollypops I'd be afraid you wouldn't know which one to taste first, and it would take so long to make sure that you might grow old before you found out, and then you wouldn't have any fun eating them."

"Oh, you're such a funny daddy!" laughed Rose.

They walked down Main Street, and soon came to Mr. Bunker's real estate office. He hurried inside, followed by the children.

Mr. Bunker looked behind the door in the little room where he had his desk. The office was made up of three rooms, and in the large, outer one, were several clerks, writing at desks. Some of them knew the two little Bunker children and nodded and smiled at them.

"Where's that old coat of mine I sometimes wear?" asked Mr. Bunker of one of his clerks, when the office door had been opened but no garment was found hanging behind it.

"Do you mean that ragged one?" asked the clerk, whose name, by the way, was Donlin—Mr. Donlin.

"That's the one I mean," said Mr. Bunker. "I stuck some real estate papers in the pocket of that coat yesterday when I went out to the lumber pile with Mr. Johnson, and now I want them. I must have left them in the pocket of the old, ragged coat."

"If you did they're gone, I'm afraid," said Mr. Donlin.

"Gone? You mean those papers are gone?"

"Yes, and the old coat, too. They're both gone. If there were any papers in the pocket of that old coat they're gone, Mr. Bunker."

"But who took them?" asked the real estate man, much worried.

"Why, it must have been that old tramp lumberman," answered the clerk. "Don't you remember?"

"What tramp lumberman?" asked Mr. Bunker.

"It was this way," said Mr. Donlin. "After you went out to the lumber pile with Mr. Johnson—and I saw you had on the old coat—you came back in here and hung it up behind the door."

"And the valuable papers were in the pocket," said Mr. Bunker. "I remember that."

"Well, perhaps they were," admitted the clerk. "Anyhow, you hung the ragged coat behind the door. And just before you went home for the night an old tramp came in. Don't you remember? He was red-haired."

"Yes, I remember that," said the children's father.

"Well, this tramp said he used to be a lumberman, but he got sick and had to go to the hospital, and since coming out he couldn't find any work to do. He said he was in need of a coat, and you called to me to give him your old one, as you were going to get another. Do you remember that?"

"Oh, yes! I certainly do!" cried Mr. Bunker. "I'd forgotten all about the tramp lumberman! And I did tell you to give him my old coat. I forgot all about having left the papers in it. I was so busy talking to Mr. Johnson that I never thought about them. And did the tramp take the coat?"

"He did, Mr. Bunker. And he said to thank you and that he was glad to get it. He went off wearing it."

"And my papers—worth a large sum of money—were in the pocket!" exclaimed Mr. Bunker. "I never thought about them, for I was so busy about selling Mr. Johnson the lumber. It's too bad!"

"I'm sorry," said the clerk. "If I had known the papers were in the old coat I'd have looked through the pockets before I gave it to the tramp."

"Oh, it wasn't your fault," said Mr. Bunker quickly. "It was my own. I should have remembered about the papers being in the coat. But do you know who that tramp was, and where he went?"

"I never saw him before," replied Mr. Donlin, "and I haven't seen him since. Maybe the police could find him."

"That's it! That's what we'll have to do!" cried Mr. Bunker. "I shall have to send the police to find the old lumberman; not that he has done anything wrong, but to get back my papers. He may keep the coat. Very likely he hasn't even found the papers. Yes, I must tell the police!"

But before Mr. Bunker could do this in came the postman with the mail. There were several letters for the real estate dealer, and when he saw one he exclaimed:

"Ah, this is from Grandma Bell! We must see what she has to say!"

Daddy Bunker opened the letter, which was written to him by his wife's mother—the children's grandmother—and when he had read a few lines, he exclaimed:

"Oh, ho! Here is news indeed! Good news!"

"Oh, what is it?" asked Russ. "Did grandma tell you in the letter that the tramp lumberman left your papers at her house?"

Daddy Bunker looked at his little boy and girl. And, on their part, Russ and Rose looked at daddy. They were thinking of two things—the letter from Grandma Bell and Mr. Bunker's real estate papers that the tramp lumberman had carried off in the old coat. Russ and Rose didn't know much about real estate—except that it meant houses and barns and fields and city lots. And they didn't know much about valuable real estate papers, but they did know their father was worried about something, and this made them feel sad.

"Has grandma got your papers?" asked Russ again.

"Oh, no, little Whistler," answered Mr. Bunker with a laugh. "She doesn't even know I have lost them."

"But what's the letter about?" asked Rose.

"It's a letter from Grandma Bell inviting us all up to her home at Lake Sagatook, in Maine, to spend part of the summer," answered Mr. Bunker. "Grandma Bell wants us to come up to Maine, and have a good time."

"Oh, can we go?" cried Russ, and, for the moment, he forgot all about his father's lost papers.

"Oh, won't it be fun!" cried Rose. "I love Grandma Bell!"

"Yes, I guess every one who knows her does," said Mr. Bunker, for he was as fond of his wife's mother as he was of his own, who was the children's Grandma Ford.

"When can we go?" asked Russ.

"Oh, it's too soon to settle that part," answered his father. "We'll have to take this letter home and talk it over with mother. Then I must see if I can't get the police to find this red-haired tramp lumberman who is carrying those valuable papers around in my old coat. It's queer I never thought that I put them in the pocket. Very queer!"

"Maybe the tramp will bring them back," said Rose after a bit. "Lots of times, when people find things, they bring them back."

"Yes, that's so, he might do it, if he is honest," said Mr. Bunker. "But perhaps he isn't, and maybe he has not yet looked in the pockets of the coat. But I'll just telephone to the police, and see if any of them have seen the tramp that came to my office."

There were not many policemen in Pineville, and most of them knew Mr. Bunker. He telephoned from his office to the chief, or head policeman, and asked him to be on the watch for a red-haired tramp lumberman wearing an old coat.

"Get me back the papers. I don't care about the coat—he may have that," said Mr. Bunker.

The chief promised that he and his men would do what they could, and some of the policemen at once began looking about Pineville for the tramp.

"But I guess maybe he has traveled on from here," said Mr. Bunker, as he came away from the telephone. "I'm afraid I'll never see my valuable papers again."

"Will you be so poor we can't go to Grandma Bell's?" asked Russ. That would be very dreadful, he thought.

"Oh, no, I won't be as poor as that," answered Daddy Bunker with a smile. "We'll go to see Grandma Bell all right. But I would like to get those papers."

He told the clerks in his office and some friends of his about his loss, and they promised to be on the lookout for the tramp. Then Daddy Bunker took Rose and Russ back home with him, along Main Street, in Pineville.

"Did you find them?" asked Mrs. Bunker anxiously, as she saw her husband coming up the walk toward the house. "Did you get your papers?"

"No," he answered. "I forgot that I had given the old coat to a tramp, and the papers were in one of the pockets," and he told his wife what had happened at the real estate office.

"And we got a letter from Grandma Bell!" exclaimed Rose as soon as she had a chance to speak.

"And we're going to see her—up to Lake Sagatook, in Maine," added Russ.

"No? Really?" cried Mrs. Bunker in delight. "Did you get a letter from mother?" she asked her husband.

"Yes, it came to me at the office," he answered, giving it to his wife.

"Do you think we can go?" she asked, when she had read the letter.

"Why, yes, I guess so," slowly answered Mr. Bunker. "It will do you good and the children good, too. We'll go to Grandma Bell's!"

"Oh, goody!" cried Russ, and he began to whistle a merry tune. Rose started to sing a little song, and then she said:

"Oh, but I must go in and help set the table!" for she often did that, as Norah had so much else to do at meal-time.

"All right, Little Helper!" said Mother Bunker with a smile. "We can talk about the trip to grandma's when we are eating supper."

Some of the other children heard the good news—the loss of the real estate papers did not bother them, for they were too little to worry; but they loved to hear about Grandma Bell.

"And I'm going to take some fire-to'pedos!" exclaimed Laddie. "I'm going to shoot 'em off for Fourth of July at grandma's."

Daddy Bunker shook his head.

"I think we'd better have our Fourth of July at home here, before we go," he said. "That will be next week, and we can go to Maine soon afterward. Grandma Bell doesn't like fire-crackers, anyhow. We'll shoot them off before we go."

"Goody!" cried Laddie again. Anything suited him as long as he could have fun. "We'll shoot sky-rockets, too. What makes 'em be called sky-rockets?" he asked, "Do they go up to the sky?"

"You go and ask Jerry Simms about that," suggested Mr. Bunker. "Jerry can tell you how they shot signaling rockets in the army. Trot along!"

Laddie was glad to do this. He liked to hear Jerry talk.

"Maybe he'll tell me a riddle about sky-rockets," said the little fellow.

Russ sat down on the porch and began whittling some bits of wood with his knife.

"What are you making now, Russ?" asked his father, while Mrs. Bunker went in to see that Rose was setting the table right, and that Norah had started to get the meal.

"I'm making a wooden cannon to shoot fire-crackers," the boy answered. "You can put a fire-cracker in it and light it, and then it can't hurt anybody."

"That's a good idea," said Mr. Bunker, "You can't be too careful about Fourth of July things. I'll be at home with you and the other children on that day, to see that you don't get hurt."

"Are you sure Grandma Bell wouldn't like to have us bring some shooting things down to her?" asked Russ.

"Oh, yes, I am very sure," answered his father with a laugh. "Grandma Bell doesn't like much noise. We'll have our Fourth before we go."

"That'll be fun!" said Russ, and he went on whittling at his cannon. His father did not really believe the little boy could make one, but Russ was always doing something; either whistling or making some toy.

At supper they talked about the fun they would have at Grandma Bell's. It was quite a long trip in the train, and they would be all night in the cars.

"And that'll be fun!" cried Russ. "We can all of us sleep when the train is going along."

"Can we, Daddy?" asked Laddie. "Really?"

"Oh, yes, they have sleeping-cars," said Mr. Bunker.

"Do the cars sleep?" asked Laddie, his eyes opening wide in surprise. "Oh, that's funny—a sleeping-car. And—and——Say! maybe I can think up a riddle about a sleeping-car," he added.

"You'd better think about drinking your milk, and getting good and fat, with rosy cheeks, so Grandma Bell will like to kiss them," said Mother Bunker with a laugh. "Don't think so much about riddles or sleeping-cars."

"Maybe I can think of a riddle with a sleeping-car in it and some milk, too," said Laddie.

"Perhaps you can!" laughed Daddy Bunker. "A cow in a sleeping-car would do for that."

After the children had gone to bed—each one eager to dream about Grandma Bell—Mr. and Mrs. Bunker sat up and talked about what was to be done.

"It's too bad about those papers the tramp took in the old coat," said Mrs. Bunker.

"Yes, I am sorry to lose them," said her husband. "But perhaps the tramp may be found, and I may get them back."

Russ, Rose, and all the rest of the six little Bunkers got up early next morning.

"Is It Fourth of July yet?" asked Munroe.

"No, not yet, Mun Bun," answered Rose with a laugh. "But it soon will be—in a few days."

"I'm going to finish my cannon," said Russ.

"Come on!" called Laddie to his twin sister Vi. "Let's go down and dig a hole in the sand pile."

"What for?" she asked. Violet hardly ever did anything without first asking a question about it.

"Huh?"

"What for we dig a hole?"

"To put fire-crackers in," answered Laddie. "And when they shoot off—'Bang!'—they'll make the sand go up in the air."

"Like a sky-rocket?" asked Vi.

"Yes, I guess maybe like a sky-rocket," answered Laddie.

So down to the sand pile he and his sister went. Mun Bun and Margy played in the grass in the side yard, Russ whittled away at his wooden cannon, whistling the while, and Rose, after she had done a little dusting, made a new dress for her doll.

"'Cause I want her to look nice for Grandma Bell," said the little girl.

And thus they played at these and other things, and had a good time.

A few mornings after this Russ was suddenly awakened by hearing a loud noise under his window.

"What's that?" he cried. "Thunder?"

"It's Fourth of July!" answered his father. "Some boy must have shot off a big early fire-cracker! Get up, children! It's Fourth of July, and we are going to have some fun! Get up!"

"Hurray!" cried Russ. "Hurray for the Fourth of July!"

Such fun as the six little Bunkers had! Daddy Bunker was up before any of them, to see that little fingers were not burned by pieces of punk or stray ends of fire-crackers, and before breakfast Russ and Laddie had made enough noise, their mother said, to last all day.

"It's a good thing we decided not to go to Grandma Bell's until after the Fourth;" she said. "Dear mother never could have stood this racket."

"We like it," said Russ.

He and Laddie did, and Mun Bun did not mind it very much, though he did shut his eyes and jump when a big cracker went off.

Rose, Margy and Vi didn't like the fire-crackers at all, though they didn't mind tossing torpedoes down on the sidewalk, to hear them go off with a little bang.

Mrs. Bunker was afraid some of the children might get burned or hurt with the fireworks, and she wished they hadn't had any; but Daddy Bunker promised to stay with the little folk all day, and see that they got into no danger. And he did, firing off the big fire-crackers himself.

The wooden cannon Russ made didn't work very well. The first fire-cracker that was shot off in it burst the wooden affair all to pieces.

"But I don't care," said Russ with a jolly whistle. "It made one awfully good noise, anyhow."

"To-night we'll go down to the Square and see the big fireworks," said Daddy Bunker, for the town of Pineville was old-fashioned enough to have a Fourth-of-July celebration.

"And you said we could have ice cream and cake this afternoon," said Rose to her mother.

"Yes, I did," agreed Mrs. Bunker. "Norah is freezing the cream now, and she made the cake yesterday."

"Oh, goody!" cried Laddie, clapping his hands. "Ice cream and cake. Is it chocolate cake, Mother?" he asked.

"I don't know—you'll have to ask Norah," was the answer.

"Come on, let's!" said Rose, and they ran around to the kitchen door, looking in where the good-natured cook was busy with pots and pans.

"Chocolate cake is it? Sure it's both kinds," Norah answered with a laugh. "It's regular thunder-and-lightning cake—you wait an' see!"

"Thunder-and-lightning cake! Oh, what kind is that?" asked Rose.

"Maybe it's a riddle," suggested Laddie.

"Oh, you're always thinking about riddles!" exclaimed Russ. "Come on, let's go out to the barn and have some fun in the hay," for Mr. Bunker kept a horse for driving customers about to look at real estate.

"What kind of fun can we have?" asked Vi.

"Come on, and you'll see," returned Russ.

By this time most of their fireworks had been shot off, though Daddy Bunker had insisted that they save a few for afternoon. And, making sure that the children did not have smoldering pieces of punk, which might set the barn on fire, Mrs. Bunker watched the six little tots run out there to have fun.

"Have you heard anything about the papers the tramp carried away in your old coat?" she asked her husband, who did not go to the office that day.

"No, the police couldn't find the man," answered Mr. Bunker. "I guess my papers are gone for good. But I mustn't worry about them; nor must you. I want you and the children to have a good time at Grandma Bell's."

"Oh, we always have good times there," said his wife. "I'll be glad to go. It is lovely in Maine at this time of year."

Out in the barn the children could be heard laughing and shouting.

"I hope they don't try to make any more steamboats out of old barrels, and get caught in the ruins," said Mrs. Bunker with a laugh, as she thought of the funny accident that had happened in the playroom.

"Oh, I guess they'll be all right," said Mr. Bunker. "It's quiet now, so I'll lie down and have a nap, to get ready to take them to the fireworks to-night."

The six little Bunkers had played some games in the barn—sliding down the hay, pretending an old wagon was a stage coach and that the Indians captured it—games like that—when they heard Norah calling loudly to them.

"What's she saying?" asked Laddie, who had found a hen's nest in the hay and was wondering whether he had better take in the eggs or let them stay to be hatched into little chickens. "What's Norah want, Russ? Have we got to come in?"

"She says come and get the thunder-and-lightning cake," said Russ, who was listening at the barn door.

"And ice cream! She said ice cream, too!" added Vi. "I heard her!"

"Yes, I guess she did say ice cream," admitted Russ. "Come on!" and he set out on a run toward the house.

"Wait for me! Wait for me!" begged Mun Bun, whose short legs could not go as fast as could those of Russ.

"I'll wait for you, Mun," said Rose kindly, and she turned back and took the little fellow's hand.

"Maybe all the cream'll melt if we don't run," said Mun, as he toddled along beside Rose.

"Oh, no, I guess not. Norah will save some for us," said the little girl, humming a song.

And Rose was right. Norah made all the children sit down on the side porch, and she waited until Mun and Rose—the last to arrive—reached the place, before she dished out the cream. Daddy and Mother Bunker were there, too, with their dishes, and so was Jerry Simms.

"This is better than bein' in the army," said the old soldier.

"Didn't you ever have ice cream there?" asked Russ.

"Oh, once in a while. But it wasn't at all the kind Norah can make. Sure she's a wonder at ice cream!"

"And we're going to have thunder-and-lightning cake, too!" added Rose.

"Well, I don't know what kind that is, but it sounds good on a Fourth of July," said Jerry with a laugh. "I hope it doesn't explode when I eat it, though, like a ham sandwich did once."

"Did a ham sandwich explode?" asked Russ, who always liked to hear the old soldier tell army stories.

"Well, sort of," answered Jerry. "It was over in the Philippines. I was eating my sandwich, and some of the soldiers were firing at the enemy, and the enemy was firing at us. And a shell came pretty close to where I was sitting. It went off with a bang, and a piece of the shell hit the sandwich I was just going to bite."

"It's a mercy the shell didn't hit you," said Mrs. Bunker.

"Part of it did—my hand that held the meat and bread," explained Jerry. "But it's good I wasn't biting the sandwich at the time, or I might have lost my head. However, here comes the thunder-and-lightning cake. Now we can see what it is."

Norah came out of the kitchen with two heaping plates, and, at the sight of them, the six little Bunkers said:

There were six "Ohs" and six "Ahs!" as you can imagine; one for each boy and girl.

"Is this thunder-and-lightning cake?" asked Russ.

"That's what it is," answered Norah. "It's the first time I've made it in a long while. I hope you'll like it."

"Sure they can't help it if you made it!" chuckled Jerry, who was exceedingly fond of Norah.

"Go 'long with you!" she told him, laughing.

"It does look just like thunder, it's so dark!" said Russ, biting into a slice of the cake.

"And where's the lightning?" asked Rose.

"That's the pink part," answered the cook. "You see I take some chocolate-cake dough, and mix it up with white-cake dough, and then I put in some dough that I've colored pink, and mix that through in lines and streaks, and that's the lightning," explained Norah.

And when the cake had been baked in this way, and cut, each slice showed a white part, a dark brown part and a pink, jagged streak here and there, as lightning is sometimes seen to streak through the dark clouds.

"Oh, it's awful good!" cried Laddie, as he took a second slice to eat with the home-made ice cream.

"Will it make a noise like a fire-cracker?" asked Vi, who always had some sort of question ready.

"It won't make a noise unless you drop it, darlin'," said Jerry with a laugh. "Then it'll go 'thump!'"

"Don't you dare talk that way about my cake!" said Norah. "The idea of sayin' it would make a noise if it fell."

"I was only joking" rejoined the former soldier. "The cake is so light, Norah, that I'll have to tie strings to it to keep it from goin' up to the sky like a balloon!"

"Go 'long with you!" laughed Norah, but she seemed pleased all the same.

"We're going to see balloons to-night at the fireworks," remarked Rose. "Did you ever see any, Jerry?"

"Yes, we had 'em in the army."

"Did you ever go up in one?" asked Russ eagerly.

"Once," said the former soldier.

"Oh, tell us about it!" begged Laddie, and Jerry did, while the six little Bunkers sat about him, finishing the last of their cream and cake.

Then Jerry had to go to get some gasolene for the automobile, as Mr. Bunker kept a machine, as well as a horse and carriage, and the children were left to themselves. They were thinking about the fireworks they were to see in the evening, and talking about the fun they would have at Grandma Bell's, when Russ, who got up to go down on the grass and turn a somersault, suddenly stopped and looked at a man coming up the side path.

The man was a very ragged one, and he shuffled along in shoes that seemed about to drop off his feet. He had on a battered hat, and was not at all nice-looking.

"Oh, look!" whispered Rose, who saw the ragged man almost as soon as Russ did.

"I see him!" Russ answered. "That's a tramp! I guess it's the one daddy gave his coat to with the papers in. Maybe he's come to give 'em back. Oh, wouldn't that be good!"

Six little Bunkers looked at the ragged man coming up the walk toward the porch. He was a tramp—of that even Mun Bun, the smallest of the six, was sure.

"Have you got anything for a hungry man?" asked the ragged chap, taking off his ragged hat. "I'm a poor man, and I haven't any work and I'm hungry."

"Did you bring back my daddy's papers?" asked Russ.

"What papers?" asked the tramp, and he seemed very much surprised. "I'm not the paper man," he went on. "I saw a boy coming up the street a while ago with a bundle of papers under his arm. I guess maybe he's your paper boy. I'm a hungry man——"

"I don't mean the newspaper," went on Russ, for the other little Bunkers were leaving the talking to him. "But did you bring back the real estate papers?"

"The real estate papers?" murmured the tramp, looking around.

"'Tisn't any riddle," added Laddie. "Is it, Russ?"

"No, it isn't a riddle," went on the older boy. "But did you bring back daddy's papers that he gave you?"

"He didn't give me any papers!" exclaimed the tramp.

"They were in a ragged coat," added Rose. "In the pocket."

The tramp looked at his own coat.

"This is ragged enough," he said, "but it hasn't any papers in it that I know of. I guess they'd fall out of the pockets if there was any," he added. "This coat is nothing but holes. I guess you don't know who I am. I'm a hungry man and——"

"Aren't you a lumberman, and didn't my father give you an old coat the other day?" asked Russ.

The tramp shook his head.

"I don't know anything about lumber," he said. "I can't work at much, and I'm hungry. I'm too sick to work very hard. All I want is something to eat. And I haven't any papers that belong to your father. Is he at home—or your mother?"

"I'll call them," said Rose, for she knew that was the right thing to do when tramps came to the house.

But there was no need to go in after Mr. and Mrs. Bunker. They had heard the children talking out on the side porch, and a strange man's voice was also noticed, so they went out to see what it was.

"Oh, Daddy!" cried Russ. "Here's the tramp lumberman you gave the old coat to, but he says he hasn't any papers!"

"Excuse me!" exclaimed the tramp, "but I don't know what the little boy is talking of. I just stopped in to ask for a bite to eat, and he and the other children started talking about a lumberman and some papers in a ragged coat. Land knows my coat is ragged enough, but I haven't anything belonging to you."

Mr. Bunker looked sharply at the ragged man, and then said:

"No, you aren't the one. A tramp lumberman did call at my real estate office the other day, and I told one of my clerks to give him an old coat. In the pocket were some valuable papers. But you aren't the man."

"I know it, sir!" answered the tramp. "This is the first time I've been here. I'm hungry and——"

"I'll tell Norah to get him something to eat," said Mrs. Bunker, who was kind to every one.

And while she was gone, and while the six little Bunkers looked at the ragged man, the children's father talked to him.

"I'd like to find that tramp lumberman," said Mr. Bunker. "I gave him the coat because he needed it more than I did, but I didn't know I had left the papers in the pocket. You're not the man, though. I didn't have a very good look at him, but he had a lot of red hair on his head: I saw that much."

"My hair's black—what there is of it," said the ragged man. "But I don't know anything about your papers. But if I see a red-haired lumberman in my travels around the country, I'll tell him to send you back the papers."

"That will be very kind of you," said Mr. Bunker, "as I need them very much. Do you think you might meet this red-haired lumberman tramp, who has my old coat?"

"Well, I might. You never can tell. I travel about a good bit, and I meet lots of fellers like myself, though I don't know as I ever saw a lumberman."

"This man wasn't a regular tramp," said Mr. Bunker. "He was only tramping around looking for work, and he happened to stop at my place."

"That's like me," said the black-haired tramp. "I'm looking for work, too. Got any wood that needs cutting?"

"Not now," said Mr. Bunker with a smile. "Jerry Simms cuts all my wood. But I'll give you some money, and maybe that will help you along, and the cook will fix you something to eat."

"That's very kind of you," said the tramp. "And if ever I see the man with your papers I'll tell him to send 'em back." "Please do" begged Mr. Bunker.

By this time Norah had wrapped the tramp up a big paper bag full of bread and meat, with a piece of pie. Tucking this under his arm, he shuffled off to go to some quiet place to eat.

Soon it was time to go to the square in the middle of the city, where the fireworks were to be shown. The six little Bunkers, talking over the fun they had had that day, and thinking of the good times they were to have at Grandma Bell's, walked along with their father and mother. Behind them came Norah and Jerry Simms.

"Maybe the tramp will come to see the fireworks," said Rose, who was walking beside Russ.

"You mean the red-headed one that has daddy's papers?"

"No, I mean the one that came begging at our house to-night."

"Well, maybe he will," admitted Russ. "If I was a tramp I'd walk all around and go to every place that I was sure they were going to have fireworks."

"So would I," said Rose. "I love fireworks."

"But you couldn't be a tramp," declared her brother.

"Why not?" Rose wanted to know.

"'Cause you're a girl, and only men and boys are tramps. I could be a tramp, but you couldn't."

And then the fireworks began, and the six little Bunkers thought no more about tramps, missing papers, or even about the visit to Grandma Bell's for a time, as they watched the red, green and blue fire, and saw the sky-rockets, balloons and other pretty things floating in the air.

If the red-haired tramp, or the one for whom Norah had put up the lunch that evening, came to the fireworks, the six little Bunkers did not see the ragged men.

They stayed until the last pinwheel had whizzed itself out in streams and stars of colored fire, until the last sky-rocket had gone hissing upward toward the clouds, and until the last glow of red fire had died away in the sky.

"Now we'll go home!" said Mother Bunker. "You tots must be tired. You've had a full day, for you were up early."

"But we've had lots of fun," said Russ, "piles of it."

"And now we'll get ready to go to Grandma Bell's, won't we?" asked Rose.

"Yes. To-morrow and for the next few days we'll be busy getting ready to go to Maine," said Mrs. Bunker.

"I want a balloon!" suddenly said Mun Bun. He had not done much talking that evening. Probably it was because he was too excited watching the fireworks. It was the first time he had been taken to the evening celebration.

"Do you mean you want to go to Grandma Bell's in a balloon?" asked his father. "Maybe you mean you're so tired you can't walk any more, and you want a balloon to ride in. Well, Mun Bun, we can't get a balloon now, but I can carry you, and that will be pretty nearly the same, won't it?"

"I want a balloon," said the little boy again, "but I want you to carry me, too. Can't I have a balloon, Daddy?" and he nestled his tired head down on his father's shoulder. Norah was carrying Margy, but the other little Bunkers could walk.

"A balloon, is it?" said Mun's father. "Do you mean a fire-balloon?"

"No, they burn up," said Mun Bun, in rather sleepy tones. And, in truth, several of the paper balloons sent up that evening had caught fire. "I want a big balloon I can ride in," he said, "like Jerry told about. I want to go up in a balloon!"

"Well, maybe you'll dream about one," said Mother Bunker with a laugh. "And that will be better than a real one, because if you fall out of a dream balloon you land in bed. But if you fall out of a real balloon you may land in the river."

Mun Bun did not answer. He was asleep on his father's shoulder.

The next day, between times of walking around the yard looking for fire-crackers that, possibly, hadn't exploded the day before, and finding stray torpedoes, the six little Bunkers talked of the fun they had had. They went into the house, now and then, to see how Mother Bunker and Norah were coming on with the packing. For a start had been made in getting ready to go to Grandma Bell's, now that the Fourth of July was passed.

Mrs. Bunker was so busy that she did not keep as close watch over the children as usual, and it was nearly time for lunch before she thought of them.

"Norah, see if they're all in the yard, please," she said. "And count them, to be sure all six are there. Then we'll get them something to eat, and do some more packing this afternoon."

Norah looked out in the yard.

"I see only five of 'em, ma'am," she reported.

"Which one is gone?" asked Mrs. Bunker quickly.

"I don't see Mun Bun," said the cook.

Just then Rose came running into the house.

"Oh, Mother!" she cried. "Guess where Mun Bun is!"

"I haven't time to guess!" said Mrs. Bunker. "Tell me quickly, Rose! Has anything happened to him?"

"I—I guess he's all right," answered Rose, who was out of breath from running. "But he's standing under a tree up the street, and he won't come home."

"He won't come home?" repeated Mrs. Bunker. "Why won't he come home, Rose?"

"'Cause his balloon is caught. He's got hold of the string and his balloon is up in the tree and he won't come home. He says he's going to take a ride up to the sky!"

"Oh, goodness me! what has happened now?" exclaimed Mrs. Bunker. "Norah!" she called. "Come! Something is the matter with a balloon and Mun Bun! We must go see what it is!"

One or the other of the six little Bunkers was always, so it seemed to their mother, in trouble of some sort, and she or Norah or Jerry Simms or their father had to drop anything they might be doing to rush to the help of the child who had gotten itself into something or some place it should not have got into.

Norah O'Grady, the cheerful cook for the six little Bunkers, saw their mother hurrying out of the house with Rose.

"What's the matter, Mrs. Bunker?" asked Norah. "Is there a fire, and are ye goin' for a policeman?"

Firemen and policemen, aside from Jerry Simms, were Norah's two chief heroes.

"No, there isn't a fire, Norah" answered Mrs. Bunker. "But Rose just told me that Mun Bun is caught up in a tree with a balloon, and I've got to go and get him down. Maybe you'd better come, too."

"Better come! I should say I had!" cried Norah, quickly taking off her apron. "The poor little lad caught up in a balloon! The saints preserve us! 'Tis probably one of them circus balloons, or maybe a German airship came along and caught him up! The poor darlin'!"

"Oh, no!" exclaimed Rose, as she trotted along with her mother and Norah, "Mun isn't in a balloon. His balloon is caught in a big tree and the little darlin' won't come away and——"

"It couldn't be much worse!" gasped Norah. "We'll have to get a fireman with a long ladder, 'tis probable, to get him down."

"I don't see how it could have happened," said Mrs. Bunker. "He was in the yard playing, a little while ago. The next time I looked he was gone. Where did the balloon come from, Rose?"

"Mun Bun bought the balloon!" said the little girl.

"He bought it?" cried Norah and Mrs. Bunker.

"Yes, it's a five-cent one. He had five cents that Jerry Simms gave him, Mun had, and he bought the balloon, and it had a long string to it, and it got caught up in a tree—the balloon did—and Mun Bun's got hold of the string and he won't come away, 'cause if he does he'll maybe break the string and the balloon and——"

Rose had to stop, she was so out of breath, but she had told all there was need to tell.

Mrs. Bunker and Norah, who had reached the street and could look down and see Mun Bun standing under a tree not far away, came to a sudden stop.

"And then the little darlin' isn't caught up by a German airship?" asked the cook.

"No. It's just a balloon he bought with the five cents Jerry gave him," explained Rose, "and it's caught in a tree, and——"

"I see how it is," said Mrs. Bunker, and she laughed. "Mun Bun doesn't want to come away without his toy balloon. We must get it for him, Norah!"

"Sure, that we will! The saints be praised he isn't flyin' above the clouds this blessed minute!" and with Norah, now laughing also, the three of them went to where Mun stood under the tree. Caught on one of the branches overhead was a big red balloon. It was fast to a string, and the little boy held the other end of the cord.

"I can't get it down!" he exclaimed.

"Well, it's a good thing you didn't climb up after it," said his mother. "We'll get it down for you, Mun."

She took hold of the string, and Norah, finding a long stick, carefully poked it up among the tree branches until she had loosed the toy balloon. Then it floated free, and Mun Bun could walk along with it floating on the end of the string above his head.

"It's a awful nice balloon," he said. "If it was bigger I could have a ride in it like Jerry did in the one when he was in the army."

"Well, I'm glad it isn't any bigger," said Mrs. Bunker. "Small as it is, you gave us enough trouble with it, Mun."

"But Mun Bun's all right! Norah was scared about him," said the girl, hugging the little boy close to her as they all walked back toward the house.

"Where did you get the balloon?" asked Mrs. Bunker.

"Down at Mrs. Kane's store," answered Mun, mentioning a little toy and candy shop on the block on which the six little Bunkers lived. They spent all their spare pennies there.

And it was in bringing his toy balloon home, on the end of a long string, letting it float in the air over his head that Mun Bun had had the accident at the tree when the blown-up rubber bag got caught in the branch. He wouldn't leave it, of course, and Rose ran to tell her mother. That's how it all happened.

"Well, come in to lunch now!" called Mrs. Bunker to the other children, who were, playing in the yard. "And don't go away from the house this afternoon. It's quite warm, and I don't want any of you to go off in the blazing sun. If you do we can't go to Grandma Bell's."

This was enough to make them all promise they would spend the afternoon in the shade near the house, while Mrs. Bunker and Norah went on with the packing of the trunks. A great many things must be taken along on the visit to Maine, when so many children have to be looked after. They used up much clothing.

"How long're we going to stay at Grandma Bell's?" asked Russ, as he left the dining-room after lunch.

"Oh, perhaps a month," his mother answered. "She told us to come and stay as long as we liked, but I hardly think we shall be there all summer."

"Shall we come back home?" asked Rose.

"I hardly know," said Mrs. Bunker. "We may go to visit some of your cousins or aunts—land knows you have enough!"

"Oh, wouldn't it be fun if we could go out West to Uncle Fred's ranch?" cried Russ.

"I'd like to go see Cousin Tom at the seashore," put in Rose. "I love the seashore."

"I like cowboys and Indians!" exclaimed Russ.

"Could we go see Aunt Jo, in Boston?" asked Laddie. "I'd like to go to a big city like Boston."

"Maybe we could go there, some day," said Mrs. Bunker. "But why would you like to go there, Laddie?"

"'Cause then maybe I could hear some new riddles. I didn't think up a new one—not in two whole days!"

"My! That's too bad!" said Mr. Bunker, who had come home to lunch, and who had heard all about Mun's balloon. "I'll give you a riddle, Laddie. Why does our horse eat oats?"

"Wait a minute! Don't tell me!" cried the little boy. "Let me guess!"

He thought hard for a few seconds, and then gave as his answer:

"Because he can't get hay."

"No, that isn't it," said Mr. Bunker. And when Laddie had made some other guesses, and when Russ, Rose and the remaining little Bunkers had tried to give a reason, Daddy Bunker said:

"Our horse eats oats because he is hungry, the same as any other horse! You mustn't always try to guess the hardest answers to riddles, Laddie. Try the easy ones first!"

And then, amid laughter, Mr. Bunker started back to the office.

"Have you found that red-haired tramp yet, Daddy?" asked Russ. "And did you get back your papers?"

"No, Russ, not yet. And I don't believe I ever shall."

"Maybe I could find him if you'd let me come down to your office," went on the little boy.

"Well, thank you, but I don't believe you could," said Mr. Bunker. "You'd better stay here and help your mother pack, ready to go to Grandma Bell's."

Out in the shady side yard some of the little Bunkers were playing different games. Mun and Margy were making sand pies, turning them out of clam shells on to a shingle, and letting them dry in the sun. Mun's red balloon floated in the air over the heads of the children, the string tied fast to a peg Russ had driven into the ground.

Russ, after having done this kindness for his little brother, began to whistle a merry tune and at the same time started to nail together a box in which he said he was going to take some of his toys to Grandma Bell's. Rose had taken her doll and was sitting under a tree, making a new dress for her toy, and Laddie and Vi had gone down to the little brook which bubbled along at the bottom of the green meadow, which was not far from the house. This brook was not very deep or wide. It flowed into Rainbow River, and was a safe place for the children to play.

Laddie and Vi had taken off their shoes and stockings before going down to paddle in the water, and after a while Russ, stopping in his work of hammering the box to look for more nails, heard Laddie calling out in a loud voice:

"Oh, Vi! what made the boat sink? What made the boat sink?"

At the same time Vi gave a loud shriek.

Russ dropped his hammer and started to run toward the brook.

"What's the matter?" called his mother, who saw him running.

"I don't just know," answered Russ, over his shoulder, "but I guess Laddie has a new riddle. He's hollering about why does a boat sink. But Vi's crying, I think."

"Oh, my!" exclaimed Mrs. Bunker, again stopping in her work of packing a trunk. "I hope those children haven't fallen into the brook!"

Led by Russ, Mrs. Bunker and Norah hurried down to the brook that ran through the green meadow. It was just like the time they ran when Rose called them about Mun's balloon.

"Did you see anything happen, Russ?" asked his mother.

"No'm, I didn't," he answered. "I was making a box to take some of my things to Grandma Bell's, and I heard Vi yell and Laddie asking a riddle."

"Asking a riddle?"

"Well, it sounded like a riddle," Russ answered. "He kept saying: 'What made the boat sink? Oh, Vi, what made the boat sink?'"

"I hope it was only a riddle, and that nothing has happened," said Mrs. Bunker.

"Maybe it'll be no worse than Mun and his balloon," said Norah. "Anyhow, I can see the two children!" and she pointed across the green meadow to the brook. "They seem to be all right."

There, on the grassy bank, was Laddie jumping up and down, and pointing to something in the water. And the something was Vi though she appeared to be out in the middle of the brook, in a part where it was deep enough to come over the knees of Russ.

"What's the matter, Laddie?" asked his mother. "Has anything happened to Vi?"

"She's in the boat, and it's sunk," was the answer. "Oh, what made the boat sink?"

"Silly boy! Stop asking riddles at a time like this!" cried Mrs. Bunker. "What do you mean, Laddie?"

"It isn't a riddle at all," he answered. "The boat did sink and Vi is in it. What made it?"

"A boat! Sure there's no boat on the brook, unless the boy made one himself," said Norah.

"I did make one—out of a box, and Vi was riding in it, but it sank," said Laddie. "What made it sink?"

Then Mrs. Bunker, Norah and Russ came near enough to the shore of the brook to see what had happened. Out in the middle, standing in a soap box, was Violet. The little girl was crying and holding out her hands to Laddie, who seemed quite worried and excited.

"She's sunk! She's sunk!" he said over and over again.

"Be quiet, silly boy!" ordered his mother, who saw that Vi was in no danger. "We'll get her out. Why didn't you wade out to her yourself, and bring her to shore?"

"'Cause I thought maybe something was out there," said Laddie.

"Something out there? What do you mean?" asked his mother.

"I mean something that made the boat sink—something that pulled it down in the water with Vi. A shark maybe, or a whale!"

"Nonsense!" laughed Mrs. Bunker. "There are only little baby fishes in the brook."

"But something made the boat sink!" insisted Laddie.

"We'll see about that when we get Vi to shore," said Mrs. Bunker. "Come on," she called to the little girl. "Wade to shore, Vi. You have your shoes and stockings off, haven't you?"

"Oh, yes, Mother."

"Then wade to shore. You're all right."

So Vi stepped out of the soap box, which Laddie had called the boat, and started for shore. The box floated down the brook, and Russ ran out on a little point of land to catch hold of it when it should float to him.

"Now you're all right," said Mrs. Bunker to her little girl, as Vi came ashore. "But what happened?"

"We were playing sailor," explained Laddie, "and I made the boat out of a box. Then Vi went for a ride, but the boat sank. What made it sink, Vi?"

"'Cause it's full of cracks and holes—that's why!" answered Russ, who had caught the soap box as it floated down to him. "Look! It let in a lot of water, and that's what made it sink," he went on, as he held out the play boat.

The bottom and sides of the box were filled with many holes, from which the water now dripped. Laddie told how he had set it afloat in the brook, with Vi as a passenger. He had pushed her out from shore, hoping to give her a nice ride, but in the middle of the stream the boat went down, and Vi was frightened—or maybe just cross because she was not getting the ride she expected. She screamed. Laddie couldn't understand why the boat sank, and called out to know. That was when Russ heard them.

"But you're all right now," said Mrs. Bunker. "And it's so warm to-day that wading in the brook won't hurt you. Only don't upset and fall in. I don't believe you can ride in your boat, Laddie. It won't float when it leaks so much."

"'Course not," said Russ, who knew something about boats. "You got to stuff up all the cracks and holes with putty, Laddie."

"All right; I'll do that," said the little fellow. "I like a boat. I'll give you a nice ride, Vi, a real long one, after I stuff up the holes."

"No, I guess I don't want to ride in the boat any more," said the little girl, who was wading in the shallow water near shore, "This is more fun."

"Well, I'll go in the boat myself," said Laddie, taking the box from his brother. "Got any putty?" he asked.

"No. But maybe Jerry Simms has," answered Russ. "He was putting a new window glass in the barn yesterday, and he had putty then."

Laddie ran off to beg some putty from the good-natured Jerry, and Vi, after paddling about a little longer in the brook, went back to the house with her mother and Norah.

"I guess I'll make me a boat, too," decided Russ. "I can fix the box for my things to-morrow."

He went to the barn with Laddie, and soon the two boys were building "boats" out of soap boxes, stuffing the cracks and holes with putty which Jerry gave them.

Then they went down to the brook and floated the boxes. They did not sink so quickly as had the one with Vi in it, and Russ and Laddie had lots of fun until supper time.

"I'm so tired I don't know what to do!" said Mrs. Bunker after supper. "I've packed two trunks, and I've helped rescue Mun Bun from a balloon and Vi from a sinking boat that wasn't a riddle after all." And the whole family, including the six little Bunkers, laughed as they thought of the queer things that had happened that day.

"I'll tell you what we can do," said Daddy Bunker. "It's early, and there is a nice moving picture show in town. We'll all go down and see it. That will rest you, Mother."

"Oh, yes! Let's go!" cried Rose.

And so they did.

The show was very nice, and there were some funny pictures. But Mun and Margy fell asleep before the show was over, and might have had to be carried home, only Jerry Simms came along in the automobile, which he had taken down to the shop to be repaired, and they rode to the house in that.

"Are we going to take our automobile with us to Grandma Bell's?" asked Russ.

"No, it's too far," his father answered. "But we can hire one there if we need one. Grandma hasn't one, I believe."

"She doesn't like to ride in them," said Mrs. Bunker. "Mother is old-fashioned. She has a carriage and a big carry-all."

"But we'll have fun there, anyhow, won't we?" asked Russ.

"I'm sure I hope so," his father answered.

The next few days were busy ones. More trunks were packed, Russ finished making his box for his things, and Laddie started to make one also. But he couldn't drive nails very straight, and his box fell apart almost as fast as he made it.

"I don't guess I'll take one," he said. "I'll put my things in your box, Russ."

"No, you can't," said the older boy. "There won't be room. But I'll make you a box for your own self," and this he did, much to Laddie's delight.

The other children brought from the playroom so many toys they wanted taken along that Mrs. Bunker said there would be no room in the trunks for anything else if she took all the youngsters piled up for her. So she picked out a few for each boy and girl, and put their best toys in.

At last the day came when they were to take the train for Grandma Bell's. Daddy Bunker had left one of his men in charge of the real estate office for the time he was to be away.

"And will that man find the red-haired lumber tramp that took your papers in the old coat?" asked Rose.

"I hope so," answered her father.

But it was not to happen that way, as you shall see.

The journey to Grandma Bell's was a long one. To get to Lake Sagatook, in Maine, the Bunkers would have to travel all of one afternoon, all night and part of the next day. They would sleep in the queer little beds on the train.

"And that'll be a lot of fun!" said Russ to Rose.

"Oh, yes, lots!" she agreed.

At the last minute it was found that many things which needed to be taken could not be put in any of the trunks.

"Make a big bundle of them," said Daddy Bunker. "Wrap up all the extra things in a bundle and roll 'em in a blanket. We can express that as we could a trunk."