Our 'Arry Laureate.

Our 'Arry Laureate.

DEAR CHARLIE,—Spring's on us at last, and a proper old April we've 'ad,

Though the cold snap as copped us at Easter made 'oliday makers feel mad.

Rum cove that old Clerk o' the Weather; seems somehow to take a delight

In mucking Bank 'Oliday biz; seems as though it was out of sheer spite.

When we're fast with our nose to the grindstone, in orfice or fact'ry, or shop,

The sun bustiges forth a rare bat, till a feller feels fair on the 'op;

But when Easter or Whitsuntide's 'andy, and outings all round is in train,

It is forty to one on a blizzard, or regular buster of rain.

It's a orkud old universe, CHARLIE, most things go as crooked as Z.

Feelosophers may think it out, 'ARRY ain't got the 'eart, or the 'ead;

But I 'old the perverse, and permiskus is Nature's fust laws, and no kid.

If it isn't a quid and bad 'ealth, it is always good 'ealth and no quid!

'Owsomever it's no use a fretting. I got one good outing—on wheels;

For I've took to the bicycle, yus,—and can show a good many my 'eels.

You should see me lam into it, CHARLIE, along a smooth bit of straight road,

And if anyone gets better barney and spree out of wheeling, I'm blowed.

Larks fust and larks larst is my motter. Old RICHARDSON's rumbo is rot.

Preachy-preachy on 'ealth and fresh hair may be nuts to a sanit'ry pot;

But it isn't mere hexercise, CHARLIE, nor yet pooty scenery, and that,

As'll put 'ARRY's legs on the pelt. No, yours truly is not sech a flat.

Picktereskness be jolly well jiggered, and as for good 'ealth, I've no doubt

That the treadmill is jolly salubrious, wich that is mere turning about,

Upon planks 'stead o' pedals, my pippin. No, wheeling as wheeling's 'ard work,

And that, without larks, is a speeches of game as I always did shirk.

I ain't one o' them skinny shanked saps, with a chest 'ollered out, and a 'ump,

Wot do records on roads for the 'onour, and faint or go slap off their chump.

You don't ketch me straining my 'eart till it cracks for a big silver mug.

No; 'ARRY takes heverythink heasy, and likes to feel cosy and snug.

Wy, I knowed a long lathy-limbed josser as felt up to champion form.

And busted hisself to beat records, and took all the Wheel-World by storm,

Went off like candle-snuff, CHARLIE, while stoopin' to lace up 'is boot.

Let them go for that game as are mind to, here's one as it certn'y won't soot.

But there's fun in it, CHARLIE, worked proper, you'd 'ardly emagine 'ow much,

If you ain't done a rush six a-breast, and skyfoozled some dawdling old Dutch.

Women don't like us Wheelers a mossel, espech'lly the doddering old sort

As go skeery at row and rumtowzle; but, scrunch it! that makes a'rf the sport!

'Twas a bit of a bother to learn, and I wobbled tremenjus at fust,

Ah! it give me what-for in my jints, and no end of a thundering thust;

I felt jest like a snake with skyattica doubling about on the loose,

As 'elpless as 'ot calf's-foot jelly, old man, and about as much use.

Now I don't like to look like a juggins, it's wot I carn't stand, s'elp my bob;

But you know I ain't heasy choked off, dear old pal, when I'm fair on the job.

So I spotted a quiet back naybrood, triangle of grass and tall trees,

Good roads, and no bobbies, or carts. Oh, I tell yer 'twas "go as yer please."

They call it a "Park," and it's pooty, and quiet as Solsberry Plain,

Or a hold City church on a Sunday, old man, when it's welting with rain;

Old maids, retired gents, sickly jossers, and studyus old stodges live there,

And they didn't like me and my squeaker a mossel; but wot did I care.

When they wentured a mild remonstration, I chucked 'em a smart bit o' lip,

With a big D or two—for the ladies—and wosn't they soon on the skip!

'Twos my own 'appy 'unting ground, CHARLIE, until I could fair feel my feet;

If you want to try wheels, take the Park; I am sure it'll do you a treat.

I did funk the danger, at fust; but these Safeties don't run yer much risk,

And arter six weeks in the Park, I could treadle along pooty brisk;

And then came the barney, my bloater! I jined 'arf a dozen prime pals,

And I tell you we now are the dread of our parts, and espessh'lly the gals.

No Club, mate, for me; that means money, and rules, sportsman form, and sech muck.

I likes to pick out my own pals, go permiskus, and trust to pot-luck.

A rush twelve-a-breast is a gammock, twelve squeakers a going like one;

But "rules o' the road" dump you down, chill yer sperrits, and spile all the fun.

The "Charge o' the Light Brigade," CHARLIE? Well, mugs will keep spouting it still;

But wot is it to me and my mates, treadles loose, and a-chargin' down 'ill?

Dash, dust-clouds, wheel-whizz, whistles, squeakers, our 'owls, women's shrieks, and men's swears!

Oh, I tell yer it's 'Ades let loose, or all Babel a busting down-stairs.

Quiet slipping along in a line, like a blooming girl's school on the trot,

May suit the swell Club-men, my boy, but it isn't my form by a lot.

Don't I jest discumfuddle the donas, and bosh the old buffers as prowl

Along green country roads at their ease, till they're scared by my squeak, or my 'owl?

My "alarm" is a caution I tell yer; it sounds like some shrill old macaw,

Wot's bin blowed up with dynamite sudden; it gives yer a twist in the jaw,

And a pain in the 'ed when you 'ear it. I laugh till I shake in my socks

When I turn it on sharp on old gurls and they jump like a Jack-in-the-box.

I give 'em Ta-ra-ra, I tell yer, and Boom-de-ray likewise, dear boy.

'Ev'n bless 'im as started that song, with that chorus,—a boon and a joy!

Wy, the way as the werry words worrit respectables jest makes me bust;

When you chuck it 'em as you dash by, it riles wus than the row and the dust!

We lap up a rare lot of lotion, old man, in our spins out of town;

Pace, dust and chyike make yer chalky, and don't we just ladle it down?

And when I'm full up, and astride, with my shoulder well over the wheel,

And my knickerbocks pelting like pistons, I tell yer I make the thing squeal.

My form is chin close on the 'andle, my 'at set well back on my 'ed,

And my spine fairly 'umped to it, CHARLIE, and then carn't I paint the town red?

They call me "The Camel" for that, and my stomach-capas'ty for "wet."

Well, my motter is hease afore helegance. As for the liquor,—you bet!

There's a lot of old mivvies been writing long squeals to the Times about hus.

They call us "road-tyrants" and rowdies; but, lor! it's all fidgets and fuss.

I'd jest like to scrumplicate some on 'em; ain't got no heye for a lark.

I know 'em; they squawk if we scrummage, and squirm if we makes a remark.

If I spots pooty gurls when out cycling, I tips 'em the haffable nod;

Wy not? If a gent carn't be civil without being scowled at, it's hodd.

Ah! and some on 'em tumble, I tell yer, although they may look a mite shy;

It is only the stuckuppy sort as consider it rude or fie-fie.

We wos snaking along t'other day, reglar clump of hus—BUGGINS and me,

MUNGO 'IGGINS, and BILLY BOLAIR, SAMMY SNIPE, and TOFF JONES, and MICK SHEE;

All the right rorty sort, and no flies; when along comes a gurl on a 'orse.

Well, we spread hout, and started our squeakers, and gave 'er a rouser, in course.

'Orse shied, and backed into a 'edge, and it looked so remarkable rum,

That we couldn't 'elp doing a larf, though the gurl wos pertikler yum-yum;

We wos ready to 'elp, 'owsomever, when hup comes a swell, and he swore,

And—would you believe it, old pal?—went for BUGGINS, and give 'im wot for!!!

Nasty sperrit, old man; nothink sportsmanlike, surely, about sech a hact!

Them's the sort as complains of hus Cyclists, mere crackpots as ain't got no tact.

We all did a guy like greased lightning; you can when you're once on your wheel—

Stout bobbies carn't run down a "Safety," and gurls can do nothink but squeal.

That's where Wheelin' gives yer the pull! Still it's beastly to think a fine sport

And a smart lot of hathleets like hus must be kiboshed by mugs of that sort.

All boko! dear boy, those Times letters! I mean the new barney to carry,

As long as the Slops and the Beaks keep their meddlesome mawleys orf

Lady Clara Robinson (née Vere de Vere). "THANKS! HOW IS IT OMNIBUS MEN ARE SO MUCH CIVILLER THAN I'M TOLD THEY USED TO BE?"

Conductor. "YOU SEE, LADY, THERE'S SO MANY DECAYED ARISTOCRACY TRAVELS BY US NOWADAYS, THAT WE PICKS UP THEIR MANNERS!"

["One can do nothing with Railways. You cannot write sonnets on the South-Eastern."—Mr. Barry Pain, "In the Smoking-Room."]

Earth has not anything to show less fair:

Patient were he of soul who could pass by

A twenty minutes' wait amidst the cry

Of churlish clowns who worn cord jackets wear,

Without one single, solitary swear.

The low, unmeaning grunt, the needless lie,

The prompt "next platform" (which is all my eye),

The choky waiting-room, the smoky air;

Refreshment-bars where nothing nice they keep,

Whose sandwich chokes, whose whiskey makes one ill;

The seatless platforms! Ne'er was gloom so deep!

The truck toe-crusheth at its own sweet will.

Great Scott! are pluck and common-sense asleep,

That the long humbugged Public stands it still?

REDDIE-TURUS SALUTAT.—A good combination of names is to be found in an announcement of a forthcoming Concert at Prince's Hall, Piccadilly, on the evening of May 11, to be given by Mr. CHARLES REDDIE and Mr. A. TAYLOR. Briefly, it might be announced as "A. TAYLOR's REDDIE-made Concert." If REDDIE-money only taken at door, will A. TATYOR give credit? Solvitur ambulando—that is, Walk in, and you'll find out. It is to be play-time for Master JEAN GERARDY, "Master G.," who is going to perform on an Erard piano, when, as his REDDIE-witted companion playfully observes, "The youthful pianist will out-Erard ERARD."

To stave off Change, and check the loud Rad Rough rage,

Conservatism is as shield and fetter meant;

And now brave BALFOUR votes for Female Suffrage;

And RITCHIE tells us he approves of "Betterment"!

O valiant WESTMINSTER, O warlike WEMYSS,

Is this to be the end of all our dreams?

SCENE—Interior of a Foreign Law Court. Numerous officials in attendance performing their various duties in an apprehensive sort of way. Audience small but determined.

Judge (nervously). Now are we really protected from disturbance?

General in Command of Troops. I think so. The Court House is surrounded by an Army Corps, and the Engineers find that the place has not been undermined to at least a distance of a thousand feet.

Judge (somewhat reassured). Well, now I think we may proceed with the trial. Admit the accused.

[The Prisoner is bowed into the dock, and accommodated with a comfortably cushioned arm-chair.

Prisoner. Good morning. (To Judge.) You can resume your hat.

Judge (bowing to the Prisoner). Accused, I am deeply honoured by your courtesy. I trust you have been comfortable in the State apartments that have been recently supplied to you.

Prisoner (firmly). State apartment! Why it was a prison! You know it, M. le Juge, and you, Gentlemen of the Jury and Witnesses. (The entire audience shudder apprehensively.) And, what is more, my friends outside know it! They know that I was arrested and thrown into prison. Yes, they know that, and will act accordingly.

Judge (tearfully). I am sure none of us wished to offend you!

Members of the Bar (in a breath). Certainly not!

Prisoner. Well, let the trial proceed. I suppose you don't want any evidence. You have heard what I have said. You know that I regret having caused inconvenience to my innocent victims. They would forgive me for my innocent intentions. I only wished to save everybody by blowing everybody up.

The Court generally. Yes, yes!

Prisoner. Well, I have just done. And now what say the Jury? Where are they?

Foreman of the Jury (white with fear). I am, Sir,—very pleased to see you, Sir,—hope you are well, Sir?

Prisoner (condescendingly). Tol lol. And now what do you say? am I Guilty or Not Guilty?

Foreman of the Jury. Yes, Sir. Thank you, Sir. We will talk it over, Sir—if you don't mind, Sir.

Prisoner. I need not tell you that my friends outside take the greatest possible interest in your proceedings.

Foreman (promptly). Why, yes, Sir! The fact is we have all had anonymous letters daily, saying that we shall be blown out of house and home if we harm you.

Prisoner (laughing). Oh, be under no apprehension. It is merely the circular of my friends. Only a compilation of hints for the guidance of the Gentlemen of the Jury.

Foreman. Just so, Sir. We accepted it in that spirit.

Prisoner. You were wise. Now, Gentlemen, you have surely had time to make up your minds. Do you find me Guilty or Not Guilty?

Foreman (earnestly). Why, Not Guilty, to be sure.

Judge. Release the accused! Sir, you have my congratulations. Pray accept my distinguished consideration.

Prisoner (coldly). You are very good. And now adieu, and off to breakfast with what appetite ye may!

The Entire Court (falling on their knees, and raising their hands in supplication). Mercy, Sir! For pity's sake, mercy!

Ex-Prisoner (fiercely). Mercy! What, after I have been arrested! Mercy! after I have been cast into gaol!

Judge (in tears.) They thought they were right. They were, doubtless, wrong, but it was to save the remainder of the row of houses! Can you not consider this a plea for extenuating circumstances?

Ex-Prisoner (sternly). No. It was my business, not theirs. It was I who paid for the dynamite—not they. (Preparing to leave the Court.) Good bye. You may hear from me and from my friends!

Judge (following him to the door). Nay, stay! See us—we kneel to you. (To audience.) Kneel, friends, kneel! (Everybody obeys the direction.) One last appeal! (In a voice broken with emotion.) We all have Mothers!

Ex-Prisoner (thunder-stricken). You all have Mothers! I knew not this. I pardon you! [The audience utter shouts of joy, and the Ex-Prisoner extends his hands towards them in the attitude of benediction. Scene closes in upon this tableaux.

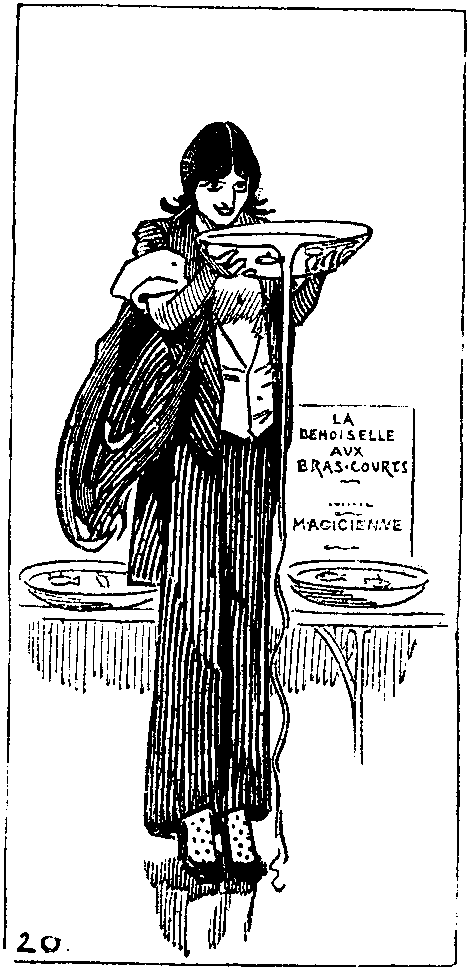

No. 20. Japanese Jenny, the Female Conjuror,

privately practicing production of glass bowl full of

water from nowhere in particular; a subject not

unnaturally associated with the name of Waterhouse, A.

No. 20. Japanese Jenny, the Female Conjuror,

privately practicing production of glass bowl full of

water from nowhere in particular; a subject not

unnaturally associated with the name of Waterhouse, A.

No. 16. It is called "A Toast. By AGNES E. WALKER." It should be called "A Toast without a Song," as it seems to represent an eminent tenor unavoidably prevented by cold, &c., when staying at home, and taking the mixture as before.

No. 19. A musical subject, "The Open C." By HENRY MOORE, A.

No. 24. "Food for Reflection; or, A (Looking) Glass too much." Black Eye'd SUSAN (hiding her black eye) after a row. The person who "calls himself a Gentleman" is seen as a retiring person in another mirror. ETTORE TITO.

No. 40. Little Bo Peep after Lunch, supported by a tree. Early intemperance movement. "Let 'm 'lone, they'll come home, leave tails b'ind 'em." JOHN DA COSTA.

No. 56. Ben Ledi. This is a puzzle picture by Mr. JAMES ELLIOT. Of course there is in it, somewhere or other, a portrait of the eminent Italian, BENJAMIN LEDI. Puzzle, to find him.

No. 287. "Forgers at Work; or, Strike while the Iron's

hot!" Portrait of the recently elected Associate making a

hit immediately on his election. Stan'up, Stanhope Forbes,

A. (and "A. 1," adds Mr. P.), prepare to receive

congratulations!

No. 287. "Forgers at Work; or, Strike while the Iron's

hot!" Portrait of the recently elected Associate making a

hit immediately on his election. Stan'up, Stanhope Forbes,

A. (and "A. 1," adds Mr. P.), prepare to receive

congratulations!

No. 83. "The Coming Sneeze." Picture of a Lady evidently saying, "Oh dear! Is it influenza!!" THOMAS C.S. BENHAM.

No. 89. "Handicapped; or, A Scotch Race from thiS TARTAN Point." JOHN PETTIE, R.A.

No. 95. Large and Early Something Warrior, pointing to a bald-headed bust, and singing to a maiden, "Get your Hair Cut!" RALPH PEACOCK.

No. 97. "Toe-Toe chez Ta-Ta; or, Oh, my poor Foot!" "Must hide it before anyone else sees it." FRANK DICKSEE, R.A.

No. 102. "Attitude's Everything; or, The Affected Lawn Tennis Player." By FREDERIC A. BRIDGMAN, probably a Lillie Bridge man.

No. 105. "Dumb as a Drum with a hole in it." Vide Sam Weller. "JOY! JOY! (G.W.) my task is done!"

No. 212.

"The Left-out Gauntlet." "Come as you are, indeed!

Nonsense. It's most annoying! Here am I got up most

expensively as a Knight in Armour, and I'm blessed if

the confounded cuss of a cusstumier hasn't forgotten

to send my right gauntlet!" John Pettie, R.A.

No. 212.

"The Left-out Gauntlet." "Come as you are, indeed!

Nonsense. It's most annoying! Here am I got up most

expensively as a Knight in Armour, and I'm blessed if

the confounded cuss of a cusstumier hasn't forgotten

to send my right gauntlet!" John Pettie, R.A.

No. 107. "Outside the Pail; or, 'Nell' the Dairing Dairymaid." Taken in the act by R.C. CRAWFORD (give him several inches of canvas, and he'll take a NELL) as she was about to put a little water out of the stream into the fresh milk pail.

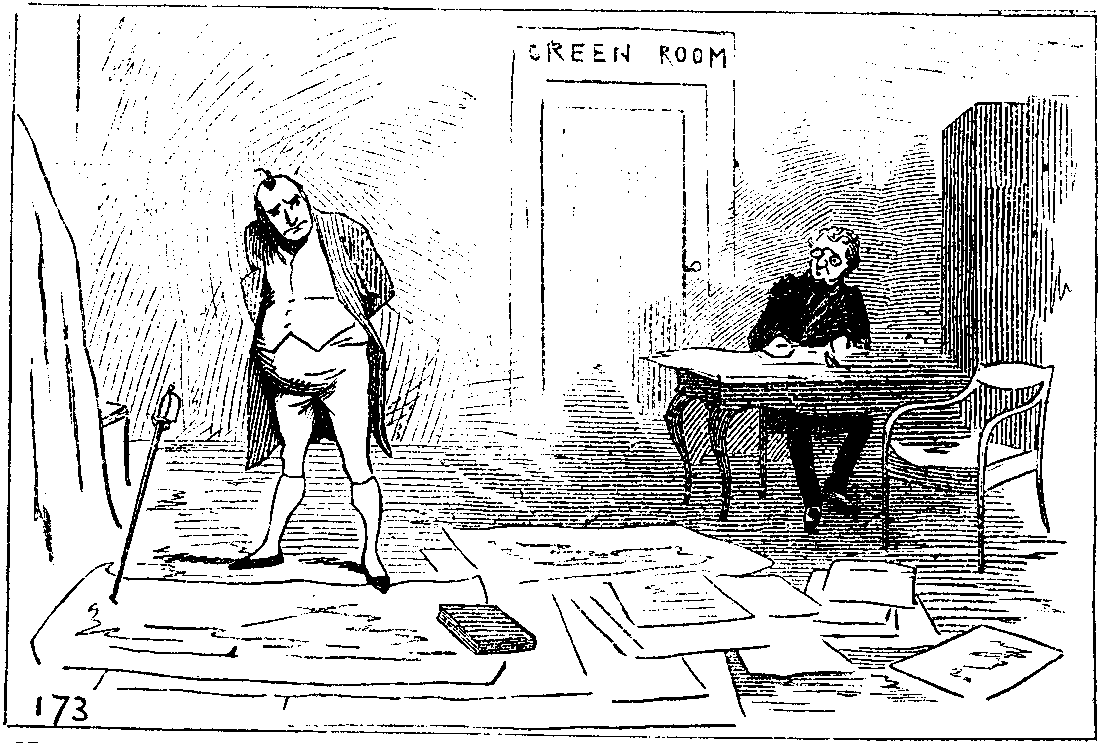

No. 173. "A

First Rehearsal." "The celebrated actor, Mr. Gommersal

of Astley's Amphitheatre, made up and attired as the

Great Napoleon, entered the Manager's room, where the

author of the Equestrian Spectacular Melodrama of 'The

Battle of Waterloo' was seated finishing the last Act.

'What do you think of this?' asked Mr. G.,

triumphantly. 'Not a bit like it,' returned the

author, sharply. 'What!' exclaimed the astonished

veteran, 'do you mean to say my make-up for Napoleon

isn't good! Well I'm ——' 'You will be, if

you appear like that,' interrupted the author

decisively,"—Vide Widdicomb's History of the

Battle of Waterloo at Astley's. W.Q. Orchardson,

R.A.

No. 173. "A

First Rehearsal." "The celebrated actor, Mr. Gommersal

of Astley's Amphitheatre, made up and attired as the

Great Napoleon, entered the Manager's room, where the

author of the Equestrian Spectacular Melodrama of 'The

Battle of Waterloo' was seated finishing the last Act.

'What do you think of this?' asked Mr. G.,

triumphantly. 'Not a bit like it,' returned the

author, sharply. 'What!' exclaimed the astonished

veteran, 'do you mean to say my make-up for Napoleon

isn't good! Well I'm ——' 'You will be, if

you appear like that,' interrupted the author

decisively,"—Vide Widdicomb's History of the

Battle of Waterloo at Astley's. W.Q. Orchardson,

R.A.

No.

344. The Reeds' Entertainment. Gallery of

Illustration. Interval during change of costume.

"Behold these graceful Reeds!" Arthur Hacker.

No.

344. The Reeds' Entertainment. Gallery of

Illustration. Interval during change of costume.

"Behold these graceful Reeds!" Arthur Hacker.

No. 130. A (Sir Donald) Currie, admirably done in P. and O. (Paint and Oil) by W.W. OULESS, R.A.

No. 211. "Blow, Blow, thou Winter Wind."—As You Like It. But we don't like it—we mean, the wind, of course. Oh, so desolate and dreary! We suppose that in order to keep himself warm, Sir JOHN must have been thoroughly wrapped up in his work when he painted this. Sir J.E. MILLAIS, Bart., R.A.

No. 228. "The Great Auk's Egg." "Auk-ward moment: is it genuine or not? He bought it at an Auk-tion; it had probably been auk'd about before, genuine or not There'll be a great tauk (!) about it," says H.S. MARKS, R.A.

No. 238. "With a little pig here and a little cow here,

Here a sheep and there a sheep and everywhere a sheep."

No. 250. "Ticklish Times; or, the First Small and Early in the Ear." "She sat, half-mesmerised, thinking to herself, 'Shall I have many dances this season?' 'You've got a ball in hand,' whispered small and early Eros Minimus. 'Ah,' she returned, dreamily, 'a bawl in the hand is indeed worth a whisper in the ear.'" From the Greek of Akephalos. W. ADOLPHE BOUGUEREAU.

No. 204. "Three Little Maids from School." A

wealth of colour. The subject is this:—After an

ample school-feast, the girls sat drowsily under an

orange-tree, when they were suddenly startled by the

appearance of a snake. "Don't be frightened, Betsy

Jane," cried Anna Maria, the eldest; "'ee won't 'urt

yer, 'ee only comes from the Lowther Harkade." Sir

Fred. Leighton, Bart., P.R.A.

No. 204. "Three Little Maids from School." A

wealth of colour. The subject is this:—After an

ample school-feast, the girls sat drowsily under an

orange-tree, when they were suddenly startled by the

appearance of a snake. "Don't be frightened, Betsy

Jane," cried Anna Maria, the eldest; "'ee won't 'urt

yer, 'ee only comes from the Lowther Harkade." Sir

Fred. Leighton, Bart., P.R.A.

No. 272. The Flying Farini Family. Nothing like bringing 'em up to the acrobatic business quite young. PHIL R. MORRIS, A.

No. 290. "Sittin' and Satin." IRLAM BRIGGS. [N.B.—Mr. P. always delighted to welcome the immortal name of BRIGGS. Years ago, one of JOHN LEECH's boys drew "BRIGGS a 'anging," and here he is,—hung!]

No. 310. First-rate portrait of a Railway Director looking directly at the spectator, and saying, "Of course, I'm the right man in the right place, i.e., on the line." Congratulations to HUBERT HERKOMER, R.A.

No. 311. Popping in on them, in not quite a friendly way, by Very Much in ERNEST CROFTS, A.

No. 317. "Strong Op-inions." A Political Picture by a Liberal Onionist. CATHERINE M. WOOD.

No. 342. A Person sitting uprightly. By BENTLEY.

No. 351. "Only a Couple of Growlers, and no Hansom!" By J.T. NETTLESHIP.

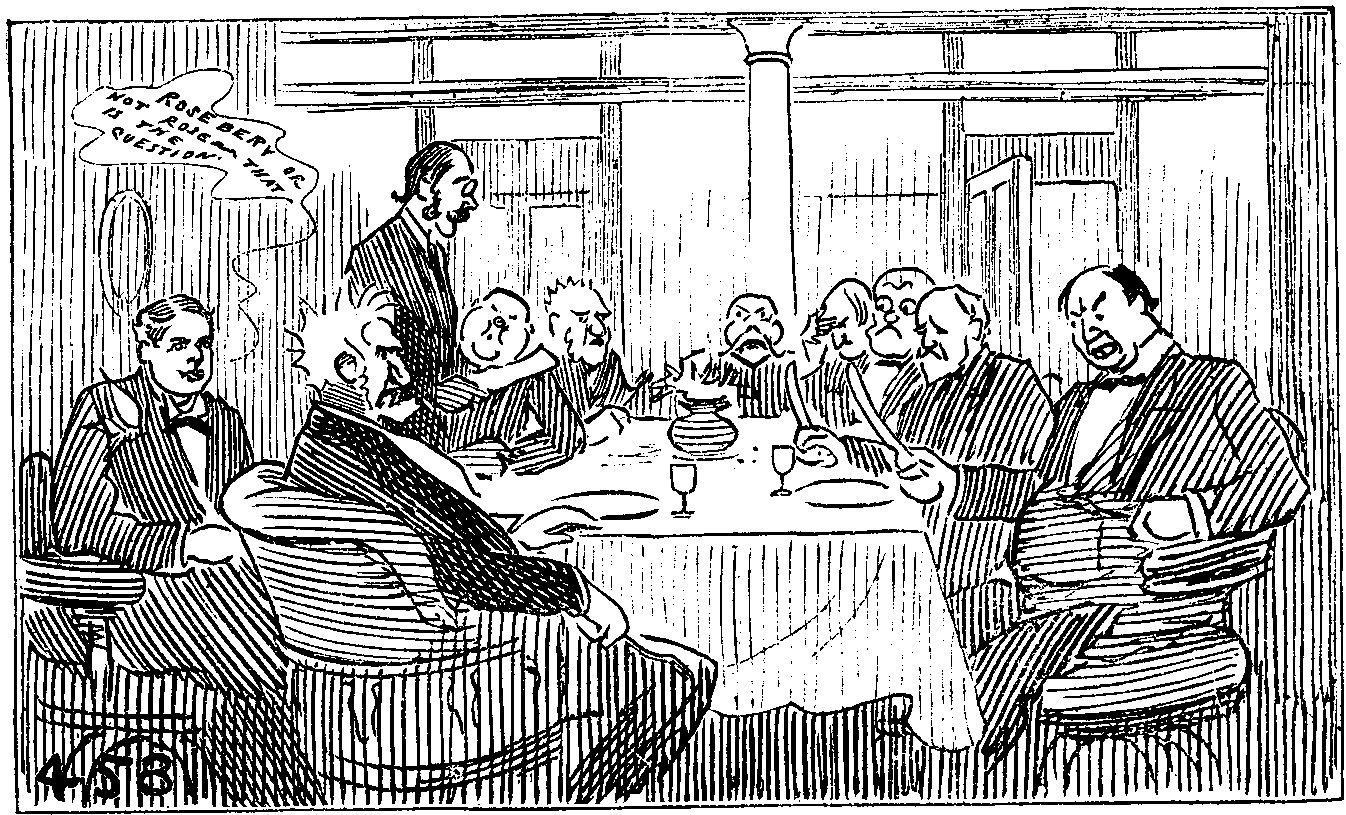

No. 458. "Peas

and War." Club Committee ordering dinner. See corner

figure (L.H. of picture) with Cookery Book. The

Steward says, "We can't have peas." Mr. J.S. B-lf-r

remonstrates strongly, "What! not have peas?

Nonsense!" That's how the row began, and they "gave

him beans." "A limner then his visage caught," and

managed the awkward subject so as to please everybody;

which the limner's name is Hubert Herkomer, R.A.

No. 458. "Peas

and War." Club Committee ordering dinner. See corner

figure (L.H. of picture) with Cookery Book. The

Steward says, "We can't have peas." Mr. J.S. B-lf-r

remonstrates strongly, "What! not have peas?

Nonsense!" That's how the row began, and they "gave

him beans." "A limner then his visage caught," and

managed the awkward subject so as to please everybody;

which the limner's name is Hubert Herkomer, R.A.

No. 373. "There is a Flower that bloometh." The Mayor of AVON, as he appeared 'avon his likeness (A 1) taken by PHIL R. MORRIS, A.

No. 412. "Hush a bye, Bibby!" Capital picture, speaks for itself. "I know that man, he comes from—Liverpool." Brought here by LUKE FILDES, R.A.

No. 440. "Poppylar Error." Old Lady (loq.). "Oh, dear! I've eaten one o' them nasty stuck-up poppies, and I do feel so—Oh! I feel my colour is gradually PALIN (W.M.)."

No. 502. "What, no Soap!" She may appear a trifle cracky, but no one can say that this picture represents her as having gone "clean mad." ANNA BILINSKA.

No. 553. Margate Sands in Ancient Times. Cruel conduct of an Ancient Warrior towards a young lady who refused to bathe in the sea. Full of life by E.M. HALE (and Hearty).

No. 575. "Poor Thing!" Touching picture of ideal patient in Æsthetic Idiot Asylum. LUCIEN DAVIS.

No. 636. "A Clever Examiner drawing him out." [N.B.—This ought to have been exhibited at A. TOOTH's Exhibition.] RALPH HEDLEY.

No. 989. La Seagull. Awful fight between a gull and a

boiled lobster. Allan J. Hook. [N.B.—Your eye is sure

to be caught by this Hook. But the picture must be looked

at from our point of view, from the opposite side of the

room.]

No. 989. La Seagull. Awful fight between a gull and a

boiled lobster. Allan J. Hook. [N.B.—Your eye is sure

to be caught by this Hook. But the picture must be looked

at from our point of view, from the opposite side of the

room.]

No. 686. Upper part of Augustus Manns, Esq. The Artist has, of course, chosen the better part. "MANNS wants but little here below," but he doesn't get anything at all, being cut off, so to speak, in his prime about the second shirt-button. Exactly like him as he was taken before the Artist at "Pettie Sessions."

No. 1041. "Every Dog must have his Dose; or, King Charles's Martyrdom." FRED HALL.

SCULPTURE.—The descriptions in the Guide are too painful. We prefer not, to give any names, but here are specimens:—"Mr. So-and-so, to be executed in bronze"; "The late Thingummy—bust!" These will suffice. Then we have No. 1997. "All Three going to Bath" by GEORGE FRAMPTON; and last, but not by any means least, a very good likeness of our old friend J.C. HORSLEY, R.A., and while we think of it, we'll treat him as a cabman and "take his number," which it's 1941, done by JOHN ADAMS-ACTON, and so, with this piece of sculpture, we conclude our pick of the Pictures with this display of fireworks; that is, with one good bust up! Plaudite et valete!

Talking "ART" is so "smart" in the first week of May,

That is "ART," which you start with a thundering A.

Simple "art" must depart; that's an obsolete way.

Some think "art" would impart all the work of to-day.

"THAT'S THE NEW DOCTOR—AND THOSE ARE HIS CHILDREN!"

"HOW UGLY HIS CHILDREN ARE!"

"WELL, NATURALLY! OF COURSE DOCTORS HAVE GOT TO KEEP THE UGLY ONES THEMSELVES, YOU KNOW!"

Humph! There you go, suspicious lurkers,

From lands less free! I grudge you room

Among my hosts of honest workers.

Had I the settling of your doom,

Your shrift were short, and brief your stay.

As 'tis, I'll watch you on your way.

A Land of Liberty! Precisely.

And curs of that advantage take.

But, if you want my tip concisely,—

We hate the wolf and loathe the snake:

And as you seem a blend of both,

To crush you I'd be little loth.

Freedom we love, and, to secure it,

Take rough and smooth with constant mind.

Espionage? We ill endure it,

But Liberty need not be blind.

Sorrow's asylum is our isle;

But we'd not harbour ruffians vile.

To flout that isle foes are not chary,

When of its shelter not in need;

But, when in search of sanctuary,

They fly thereto with wondrous speed.

Asylum? Ay! But learn—in time—

'Tis no Alsatia for foul crime.

Foes dub me sinister, satanic,

A friend of Nihilists and knaves;

Because I will not let mere panic

Rob me of sympathy with slaves,

And hatred of oppressors. Fudge!

Their railings will not make me budge.

I've taken up my stand for freedom,

I'll jackal to no autocrat;

But rogues with hands as red as Edom,

Nihilist snake, Anarchist rat,

I'd crush, and crime's curst league determine.

I have no sympathy with vermin.

Doors open, welcome hospitable

For all, unchallenged, is my style;

But trust not to the fatuous fable

That Caliban's free of my isle

With prosperous Prospero's free consent.

Such lies mad autocrats invent.

Such for some centuries they've been telling,

Crime, like an asp, I'd gladly crush

Upon the threshold of my dwelling,

But shall not join a purblind rush

Of panic-stricken fools to play

The oppressor's game, for the spy's pay!

But you, foul, furtive desperadoes,

Who, frightened now by those you'd fright,

Would fain slink off among the shadows,

To plot out further deeds of night,

Our isle's immunity you boast!—

You're reckoning without your host.

I'll keep my eye on you; my Juries

I think you'll find it hard to scare;

We worship no Anarchic furies,

For menace are not wont to care,

Here red-caught Crime in vain advances

"Extenuating Circumstances!"

Philistine Art may stand all critic shocks

Whilst it gives Private Views—of Pretty Frocks!

MR. STEVENS, the American gentleman who rode round the world on a bicycle, says, "The bicycle is now recognised as a new social force." Possibly. But certain writers to the Times on "The Tyranny of the Road," seem to prove that it is also a new anti-social force, when it frightens horses and upsets pedestrians. Adapting an old proverb, we may say, "Set a cad on a cycle and he'll ride"—well, all over the road, and likely enough over old ladies into the bargain. Whilst welcoming the latest locomotive development, we must not allow the "new social force" to develop into a new social despotism. To put it pointedly:—

We welcome these new steeds of steel,

(In spite of whistles and of "squealers,")

But cannot have the common weal

Too much disturbed by common "Wheelers"!

THE ROYAL ACADEMY BANQUET.—After the Presidential orations, the success of the evening was Professor BUTCHER's speech. His audience were delighted at being thus "butchered to make" an artistic "holiday." Prince ARTHUR BALFOUR expressed his regret that "the House of Commons did not possess a Hanging Committee." Hasn't it? Don't we now and again hear of a Member being "suspended" for some considerable time? On such occasions, the whole House is a Hanging Committee. There was one notable omission, and yet for days the air had been charged with the all-absorbing topic. "Odd!" murmured a noble Duke to himself, as, meditating many things, he stood by the much-sounding soda-water, "Odd! a lot of speeches; and yet,—not a word about Orme!"

FIRST ANARCHIST. "ENFIN, MON AMI!—VE SHALL NOT BE INTERRUPT IN ZIS FREE ENGLAND!"

BULL A1 (sotto voce). "DON'T BE TOO SURE, MOSSOO! YOU'LL FIND NO EXTENUATING CIRCUMSTANCES HERE!!"

All young girls should have definite ideas of the impression which they wish to create. The natural girl is always either impolite or impolitic. I am quite willing to allow that a girl who appears artificial is equally detestable. To be unnatural, and to appear natural, is the end at which the young girl should aim. Much, then, will depend on the choice of a pose. It should be suitable; there should be something in your appearance and abilities to support the illusion. I once knew a fat girl, with red hair (the wrong red), & good appetite, and chilblains on her fingers; she adopted the romantic pose, and made herself ridiculous; of course, she was quite unable to look the part. If she had done the Capital Housekeeper, or the Cheerfully Philanthropic, she might have married a middle-aged Rector. She threw away her chances by choosing an unsuitable pose. At the same time the reasons for your choice should never be obvious. There was another case, which amused me slightly—a dark girl, with fine eyes. She was originally intended to be a beauty, but she had some accident in her childhood that had crippled her. She had to walk with a stick, and her back was bent. She posed as a man-hater. The part suited her well enough, for she had rather a pretty wit. "But," I said to her, "it is too plainly a case of the fox and the grapes; you hate men because you are a cripple, and can never get a man to love you." She did not take this friendly hint at all nicely; in fact, since then she has never spoken to me again; but what I said to her was quite true. She was right in deciding that she had nothing to do with love; if you ever have to buy yourself a wooden leg, you may as well get a wooden heart at the same time. But her pose was too obvious—ridiculously obvious. She would have done better with something in the way of a religious enthusiasm—something very mystical. It would have been impressive.

In the matter of dress a girl can do very much towards supporting her pose; but she must have the intuitions and perceptions of an artist.

The child-like type requires great care, for the young girl in London is not naturally child-like. There should be a suggestion of untidiness about the hair; the dress should be simple, loose and sashed; nurse a kitten with a blue ribbon round its neck; say that you like chocolate-creams; open your eyes very wide, and suck the tip of one finger occasionally. Let your manner generally vary between the pensive and the mischievous; always ask for explanations, especially of things which cannot possibly be explained in public. Do not attempt this pose unless your figure is mignon and your complexion pink. Do not be too realistic; never be sticky or dirty—men do not care for it.

A capital pose for a girl with dark lines under the eyes, is that of "the girl-with-a-past." These lines, which are mostly the result of liver, are commonly accepted as evidence of soul. The dress should be sombre, trailing, and rather distraught: there is a way of arranging a fichu which of itself suggests that the heart beneath it is blighted. If you happen to possess a few ornaments which are not too expensive, distribute them among your girl-friends; say, in a repressed voice, that you do not care for such things any more. Let it be known that there is one day in the year which you prefer to spend in complete solitude. Have a special affection for one flower; occasionally allow your emotions to master you when you hear music. The hair-ornament belongs exclusively to the lower middle-classes, but wear one article of jewellery, a souvenir, which either never opens or never comes off. Smile sometimes, of course; but be careful to smile unnaturally. On all festive occasions divide your time between your bedroom and the churchyard.

Both these types demand some personal attractions; if you have no personal attractions, you must fall back upon one of the philanthropical types. The plainer you are, the more rigid will be your philanthropy. Your object will be to disseminate in the homes of the poor some of the luxuries of the rich; and, on returning, to disseminate in the homes of the rich some of the diseases of the poor. Everything about you must be flat; your hats, hair and heels must be flat; your denials must be particularly flat. Always take your meals in your jacket and a hurry, never with the rest of your family; never have time to eat enough, but always have time to brag about it.

I cannot understand why any girl should object to the assumption of a pose; and yet a girl told me the other day that she preferred to be what she seemed to be. She was an exceptional case; I disbelieved in her protestations that she was perfectly natural, and managed to get some opportunities for observation when she did not know that she was observed. I must own that she was quite truthful; she also managed to get married—suburban happiness and no position—but, as I said, she was exceptional. Personally, I feel sure that I should never have been married if I had seemed to be what I really was. I cannot understand this desire to be natural—it is so affected.

My correspondence this week is not very interesting. In spite of my disclaimer last week, I have been asked several questions which are not connected with Sentiment and Propriety. "BELLADONNA" asks my advice on rather a delicate case; she is almost engaged to a man, A., and her greatest friend is a girl, B. Happening, the other day, to open B.'s Diary by mistake for her own, she discovered that B. is also very much in love with A. What is "BELLADONNA" to do? I think the most honourable course would be to report in her own Diary a statement by A. that he loathes B., and then leave the Diary where B. might mistake it for her own. This is checkmate for B., because she cannot do anything nasty without thereby implying that she has read "BELLADONNA's" Diary.

First Voice (probably on stage). "Who's there?"

Second V. (probably in auditorium). I can't see. Is it TREE?

Third V. "Nay, answer me: stand and unfold yourself."

Fourth V. I wish I could unfold the seat to let people pass.

Third V. "You come most carefully upon your hour."

Fourth V. Why on earth can't people be more punctual?

First V. "'Tis now struck twelve."

Fourth V. About a dozen people have hit my head scrambling past in the dark.

Third V. "For this relief much thanks."

Fourth V. They seem to have got in at last.

Third V. "'Tis bitter cold."

Fifth V. Oh, EDWIN, dear, I do wish they'd send away the ghost, and turn up the lights.

Third V. "Not a mouse stirring." [Crash.

Sixth V. There goes my opera-glass! Deuce of a job to find it.

Third V. "Stand, ho!"

Seventh V. Bless my soul, Ma'am, are you aware that you're standing on my foot?

Third V. "BERNARDO has my place."

Sixth V. Here's someone taken my seat!

First V. "What, is HORATIO there?"

Eighth V. Hullo, dear boy, how are you? Couldn't see you—but now the light's a bit up—(&c., &c.).

A CRITERION OF MORALS.—Astutely doing "The Puff Preliminary" in a letter to the papers before the production of The Fringe of Society (i.e., Le Demi-monde freely adapted), Mr. CHARLES WYNDHAM observes that "there is no such class, in any recognisable degree, as the demi-monde in England." "Recognisable" is good, very good, it saves the situation, as of course the demi-monde is not, on any account, to be recognised. Cheery CHARLES evidently belongs to that half of the world which never knows what the other half is doing. If The Fringe, as it at first went in to the Licenser, had to be trimmed, CHARLES our Friend might have announced his latest version as re-"adapted from the Fringe."

"AILING AND CONVALESCENT,"—ORME. [No others count.]

(By THOMAS OF WESSEX, Author of "Guess how a Murder feels," "The Cornet Minor," "The Horse that Cast a Shoe," "One in a Turret," "The Foot of Ethel hurt her," "The Flight of the Bivalve," "Hard on the Gadding Crowd," "A Lay o' Deceivers," &c.)

["I am going to give you," writes the Author of this book, "one of my powerful and fascinating stories of life in modern Wessex. It is well known, of course, that although I often write agricultural novels, I invariably call a spade a spade, and not an agricultural implement. Thus I am led to speak in plain language of women, their misdoings, and their undoings. Unstrained dialect is a speciality. If you want to know the extent of Wessex, consult histories of the Heptarchy with maps."]

In our beautiful Blackmoor or Blakemore Vale, not far from the point where the Melchester Road turns sharply towards Icenhurst on its way to Wintoncester, having on one side the hamlet of Batton, on the other the larger town of Casterbridge, stands the farmhouse wherewith in this narrative we have to deal. There for generations had dwelt the rustic family of the PEEPS, handing down from father to son a well-stocked cow-shed and a tradition of rural virtues which yet excluded not an overgreat affection on the male side for the home-brewed ale and the homemade language in which, as is known, the Wessex peasantry delights. On this winter morning the smoke rose thinly into the still atmosphere, and faded there as though ashamed of bringing a touch of Thermidorean warmth into a degree of temperature not far removed from the zero-mark of the local Fahrenheit. Within, a fire of good Wessex logs crackled cheerily upon the hearth. Old ABRAHAM PEEP sat on one side of the fireplace, his figure yet telling a tale of former vigour. On the other sat POLLY, his wife, an aimless, neutral, slatternly peasant woman, such as in these parts a man may find with the profusion of Wessex blackberries. An empty chair between them spoke with all an empty chair's eloquence of an absent inmate. A butter-churn stood in a corner next to an ancient clock that had ticked away the mortality of many a past and gone PEEP.

"Where be BONDUCA?" said ABRAHAM, shifting his body upon his chair so as to bring his wife's faded tints better into view. "Like enough she's met in with that slack-twisted 'hor's bird of a feller, TOM TATTERS. And she'll let the sheep draggle round the hills. My soul, but I'd like to baste 'en for a poor slammick of a chap."

Mrs. PEEP smiled feebly. She had had her troubles. Like other realities, they took on themselves a metaphysical mantle of infallibility, sinking to minor cerebral phenomena for quiet contemplation. She had no notion how they did this. And, it must be added, that they might, had they felt so disposed, have stood as pressing concretions which chafe body and soul—a most disagreeable state of things, peculiar to the miserably passive existence of a Wessex peasant woman.

"BONDUCA went early," she said, adding, with a weak irrelevance. "She mid 'a' had her pick to-day. A mampus o' men have bin after her—fourteen of 'em, all the best lads round about, some of 'em wi' bags and bags of gold to their names, and all wanting BONDUCA to be their lawful wedded wife."

ABRAHAM shifted again. A cunning smile played about the hard lines of his face. "POLLY," he said, bringing his closed fist down upon his knee with a sudden violence, "you pick the richest, and let him carry BONDUCA to the pa'son. Good looks wear badly, and good characters be of no account; but the gold's the thing for us. Why," he continued, meditatively, "the old house could be new thatched, and you and me live like Lords and Ladies, away from the mulch o' the barton, all in silks and satins, wi' golden crowns to our heads, and silver buckles to our feet."

POLLY nodded eagerly. She was a Wessex woman born, and thoroughly understood the pure and unsophisticated nature of the Wessex peasant.

Meanwhile BONDUCA PEEP—little BO PEEP was the name by which the country-folk all knew her—sat dreaming upon the hill-side, looking out with a premature woman's eyes upon the rich valley that stretched away to the horizon. The rest of the landscape was made up of agricultural scenes and incidents which the slightest knowledge of Wessex novels can fill in amply. There were rows of swedes, legions of dairymen, maidens to milk the lowing cows that grazed soberly upon the rich pasture, farmers speaking rough words of an uncouth dialect, and gentlefolk careless of a milkmaid's honour. But nowhere, as far as the eye could reach, was there a sign of the sheep that Bo had that morning set forth to tend for her parents. Bo had a flexuous and finely-drawn figure not unreminiscent of many a vanished knight and dame, her remote progenitors, whose dust now mouldered in many churchyards. There was about her an amplitude of curve which, joined to a certain luxuriance of moulding, betrayed her sex even to a careless observer. And when she spoke, it was often with a fetishistic utterance in a monotheistic falsetto which almost had the effect of startling her relations into temporary propriety.

Thus she sat for some time in the suspended attitude of an amiable tiger-cat at pause on the edge of a spring. A rustle behind her caused her to turn her head, and she saw a strange procession advancing over the parched fields where—[Two pages of field-scenery omitted.—ED.] One by one they toiled along, a far-stretching line of women sharply defined against the sky. All were young, and most of them haughty and full of feminine waywardness. Here and there a coronet sparkled on some noble brow where predestined suffering had set its stamp. But what most distinguished these remarkable processionists in the clear noon of this winter day was that each one carried in her arms an infant. And each one, as she reached the place where the enthralled BONDUCA sat obliviscent of her sheep, stopped for a moment and laid the baby down. First came the Duchess of HAMPTONSHIRE followed at an interval by Lady MOTTISFONT and the Marchioness of STONEHENGE. To them succeeded BARBARA of the House of GREBE, Lady ICENWAY and Squire PETRICK's lady. Next followed the Countess of WESSEX, the Honourable LAURA and the Lady PENELOPE. ANNA, Lady BAXBY, brought up the rear.

BONDUCA shuddered at the terrible rencounter. Was her young life to be surrounded with infants? She was not a baby-farm after all, and the audition of these squalling nurslings vexed her. What could the matter mean? No answer was given to these questionings. A man's figure, vast and terrible, appeared on the hill's brow, with a cruel look of triumph on his wicked face. It was THOMAS TATTERS. BONDUCA cowered; the noble dames fled shrieking down the valley.

"Bo," said he, "my own sweet Bo, behold the blood-red ray in the spectrum of your young life."

"Say those words quickly," she retorted.

"Certainly," said TATTERS. "Blood-red ray, Broo-red ray, Broo-re-ray, Brooray! Tush!" he broke off, vexed with BONDUCA and his own imperfect tongue-power, "you are fooling me. Beware!"

"I know you, I know you!" was all she could gasp, as she bowed herself submissive before him. "I detest you, and shall therefore marry you. Trample upon me!" And he trampled upon her.

Thus BO PEEP lost her sheep, leaving these fleecy tail-bearers to come home solitary to the accustomed fold. She did but humble herself before the manifestation of a Wessex necessity.

And Fate, sitting aloft in the careless expanse of ether rolled her destined chariots thundering along the pre-ordained highways of heaven, crushing a soul here and a life there with the tragic completeness of a steam-roller, granite-smashing, steam-fed, irresistible. And butter was churned with a twang in it, and rustics danced, and sheep that had fed in clover were "blasted," like poor BONDUCA's budding prospects. And, from the calm nonchalance of a Wessex hamlet, another novel was launched into a world of reviews, where the multitude of readers is not as to their external displacements, but as to their subjective experiences.

This is the place to see the "female form divine" of all shapes and sizes. Walk up, walk up, and look at a few of the young Ladies:—

No. 13. "White Roses." E.J. POYNTER, R.A. Thorns here, evidently, judging by the young woman's look of anguish. And this is the moral POYNTER points.

No. 66. "A War Cloud." A Music-HALLÉ singing "Rule Britannia!" with proper dressings.

No. 18. "Paderewski." Surely it ought to be PATTY REWSKY, with "Miss" before the name. Moral, "Get your hair cut!"

No. 284. "Nightfall in the Dauphinée." "Might fall," it ought to be, and no wonder if she walked about on so dark a night with such a load in her arms!

No. 165. "Che sara sara." A pedestrian match in the Metropolis. In fact, Walker, London. A portrait of Sarah, after she has been let down into the punt, the shock having dislocated her shoulder. She might have kept Col. Neal's clothes round her neck to hide her back.

No. 77. This is the gem of the collection. It is by FRNND KHNPFF. Our Head Critic was so overcome by this great work that he went out to get assistance, but unfortunately, in trying to pronounce the painter's name, he dislocated his jaw, and is now in a precarious state. Our Assistant Critic, Deputy Assistant Critic, Deputy Assistant Sub-Critic, and a few extra Supernumerary Critics, then went in a body and looked at this young woman's head, apparently taken after an interview with Madame Guillotine. They looked at the head from all sides, and finally stood on their own, but they could not make head or tail of it. Any person giving information as to the meaning, and paying threepence, will receive a presentation copy of this journal.

There are other portraits of the latest fashion in young Ladies, but those mentioned above are the most remarkable in the New Girlery.

O woman, in our hours of ease,

We smile, and say, "Go as you please!"

But when there's prospect of a row,

You're best out of it anyhow.

THE TWO ARCHERS.—In the P.M.G. of Saturday last, WILLIAM ARCHER, in a signed article, criticises a book on "How to Write a Good Play, by FRANK ARCHER." In expressing his opinion of the book, WILLIAM becomes Frank—unpleasantly Frank.

While Publishers their fortunes make

And wax exceeding fat,

The Author still is like a rake.

Now, pray account for that.

Oh, what a smell from the kitchen to spur comers

Out of this room, where we think more of ham

Than HORSLEYS, of soup than STONES, hashes than HERKOMERS,

Mix MILLAIS with mutton, and LEIGHTON with lamb,

Think of salmon and cucumber, stilton and celery,

And not of the drawings at which we should look;

Reminded, when making a tour round this gallery,

But little of "Gaze," and a great deal of "Cook."

House of Commons, Monday, April 25.—Session resumed to-day after Easter Recess. As TENNYSON somewhere says, Session comes but Members linger. Not forty present when business commenced. "May as well go on." said the SPEAKER, whom everybody glad to see looking brisk and hearty after his holiday. "They'll drop in by-and-by."

So they did, but without evidence of overmastering haste or enthusiasm. Only half-dozen questions on paper; very early got to business in Committee on Indian Councils Bill; supposed to be measure involving closest interests of the great empire that CLIVE helped to make, and SEYMOUR KEAY now looks after. Appearance of House suggestive rather of some local question affecting Isle of Sheppey or Romney Marsh. Below Gangway, on Ministerial side, only MACLEAN present. Member for Oldham a sizeable man, but seemed a little lost in space. Above Gangway RICHARD TEMPLE on guard. Prince ARTHUR and GEORGIE CURZON had Treasury Bench all to themselves. Opportunity for observing how cares of office are beginning to tell on GEORGE. Growing quite staid in manner, the weight of India adding gravity to his looks, sicklying his young face o'er with pale cast of thought. Pretty to see him blush to-night when SEYMOUR KEAY made graceful allusion to his genius and statesmanlike conduct of affairs. "Approbation from Sir HUBERT STANLEY," as he later observed, "is praise indeed."

Only sign of life and movement displayed below and above Gangway opposite. SCHWANN evidently in running for BRADLAUGH's vacant place as Member for India. Fortunate in finding a party brimful of energy, enthusiasm, eloquence, and encyclopædic knowledge—MORTON, SEYMOUR KEAY, SAM SMITH, JULIUS 'ANNIBAL PICTON, SWIFT MACNEILL, and the CURSE OF CAMBORNE, who has been as far East as the Cape, and therefore knows all about India.

Some Members looking across the waste place behind MACLEAN whilst he was delivering vigorous speech, thought of poor LEWIS PELLY, who really knew something about India, and therefore would probably not have spoken had he been here to-night. A kindly, courteous, upright, valiant gentleman, who took a little too seriously the joke House had with him about the Mombasa business. Everyone recalls his luminous speech on the question, with its graphic description of forced marches "from So-and-so to So-on," dubious nights by night "from Etcetera to So-forth."

PELLY was with us when the House adjourned. In recess he, too, has made a forced march, passing from the ordinary So-on into the unmapped So-forth.

MACLEAN's speech stirred up the dolorous [pg 228] desolate House. Only one other movement. This when SEYMOUR KEAY, in one of several speeches dropped the remark, "I am sure my friends near me will bear me out when I say—" Instant commotion below Gangway. SWIFT MACNEILL on his legs; SCHWANN tumbling over PICTON; CONYBEARE cannoning against MORTON. All animated by desire to take up KEAY and carry him forth. He breathlessly explained that it was merely a figure of speech, and, they reluctantly resuming their seats, he went on to the bitter end.

Business done.—Practically none.

Tuesday.—Amid the pomps and vanities of a wicked world there is something refreshing and reassuring in spectacle of SAGE OF QUEEN ANNE'S GATE going about his daily business. One would describe him as childlike and bland, only for recollection that combination of harmless endearing epithet has been applied in another connection and might be misunderstood. A pity, for there are no other words that so accurately describe SAGE's manner when, just now, he rose to pose Prince ARTHUR with awkward question about Dissolution. Wanted to know whether, supposing Parliament dissolved between months of September and December in present year, a Bill would be brought in to accelerate Registration? Terms of question being set forth on printed paper, not necessary for the SAGE to recite them. For this he seemed grateful. It relieved him from the pain of appearing to embarrass Prince ARTHUR by a reference to awkward matters. No one could feel acutely hurt at being asked "Question No. 8." So the SAGE, half rising from his seat—so delicate was his forbearance, that he would not impose his full height on the eyesight of the Minister—"begged to ask the FIRST LORD OF THE TREASURY Question No. 8."

Quite charming Prince ARTHUR's start of surprise when he looked at the paper and saw, as if for the first time, the question addressed to him. Dear me! here was a Member actually wanting to know something about the date of the Dissolution, and what would follow in certain contingencies. As a philosopher, Prince ARTHUR was familiar with the vagaries of the average mind. He could not prevent the SAGE, in his large leisure, untrammelled by no other consideration than that of doing the greatest amount of good to the largest number, indulging in speculations. But for Her Majesty's Ministers, the contingency referred to was so remote and uncertain, that they had not even contemplated taking any steps to meet it.

Then might the SAGE assume that, if the contingency arose, the Government would act in the manner he had suggested?

No; on the whole, Prince ARTHUR, thinking the matter over in full view of the House, concluded the SAGE might hardly draw that deduction from what he had said.

The House, having listened intently to this artless conversation, proceeded to business of the day, which happily included the adoption of a Resolution engaging the Government to connect with the mainland, by telephone or telegraph, the lighthouses and lightships that twinkle round our stormy coasts. It was Cap'n BIRKBECK who moved this Resolution, seconded from other side in admirable speech by MARJORIBANKS.

Business done.—Excellent.

Wednesday.—Much surprised, strolling down to House this afternoon, to find place in sort of state of siege. Policemen, policemen everywhere, and, as one sadly observed, "not a drop to drink." Haven't seen anything like it since KENEALY used to shake the dewdrops from his mane as he walked through Palace Yard, passing through enthusiastic crowd into House of Commons, perspiring after his efforts in Old Westminster Courts. Later, when BRADLAUGH used to-give dear old GOSSET waltzing lessons, pirouetting between Bar and Table, scene was somewhat similar.

"What's the matter. HORSLEY?" I asked, coming across our able and indefatigable Superintendent striding about the Corridor, as NAPOLEON visited the outposts on the eve of Austerlitz.

"It's them Women, Sir," he said. "Perhaps you've heard of them at St. James's Hall last night? Platform stormed; Chairman driven off at point of bodkin; Reporters' table crumpled up; party of the name of BURROWS seized by the throat and laid on the flat of his back."

"A position, I should say, not peculiarly convenient for oratorical effort. But you seem to have got new men at the various posts?"

"Yes, Sir," said Field-Marshal HORSLEY. lowering his voice to whisper; "we've picked em out. Gone through the Force; mustered all the bald-headed men. They say that at conclusion of argument on Woman's Suffrage in St. James's Hall last night, floor nearly ankle-deep in loose hair. They don't get much off my men," said HORSLEY, proudly.

Very well, I suppose, to take those precautions. Probably they had something to do with the almost disappointing result. Everything passed off as quietly as if subject-matter of Debate had been India, or Vote in Committee of Supply of odd Million or two. Ladies locked up in Cage over SPEAKER's Chair, with lime-lights playing on placards hung on walls enforcing "Silence!" Cunningly arranged that SAM SMITH should come on early with speech. This lasted full hour, and had marvellously sedative effect. Some stir in Gallery when, later, ASQUITH demolished Bill with merciless logic. Through the iron bars, that in this case make a Cage, there came, as he spoke, a shrill whisper, "So young and so iniquitous!" Prince ARTHUR, dexterously intervening, soothed the angry breast by his chivalrous advocacy of Woman's Rights. As he resumed his seat there floated over the charmed House, coming "So young and so as it were from heavenly spheres above the iniquitous!" SPEAKER's Chair, a cooing whisper, "What a love of a man!"

Business done.—Woman's Suffrage Bill rejected by 175 Votes against 152.

Friday Night.—Little sparring match between Front Benches. Mr. G. and all his merry men anxious, above all things, to know when Dissolution will dawn? SQUIRE OF MALWOOD starts inquiry. Prince ARTHUR interested, but ignorant. Can't understand why people should always be talking about Dissolution. Here we have best of all Ministries, a sufficient majority, an excellent programme, and barely reached the month of May. Why can't we get on with our work, and cease indulgence in these wild imaginings? Next week, on BLANE's Motion, there will be opportunity for Mr. G. to explain his Home Rule scheme. Let him contentedly look forward to pasturing on that joy, and not trouble his head about indefinite details like Dissolutions.

This speech the best thing Prince ARTHUR has done since he became Leader.

Business done.—None.

The sunshine is cheerful, I'll call upon STELLA,

The girl I am pledged to, and ask her for tea.

It's a summer-suit day, I can leave my umbrella;

Mother Nature smiles kindly on STELLA and me.

With my silver-topped cane, and my boots (patent leather),

My hat polished smoothly, a gloss on my hair,

Yes, I think I shall charm her, and as to the weather,

I am safe—the barometer points to "Set Fair."

So I'm off—why, what's that? Yes, by Jove, there's a sputter

Of rain on the pavement!—the sunshine retires;

And I wish, oh, I wish that my tongue dared to utter

The thoughts that this changeable weather inspires.

Back, back to my rooms; I am drenched and disgusted;

In thick boots and an ulster I'll tempt it again;

And accurst be the hour when I foolishly trusted

The barometer's index, which now points to "Rain."

Well, I'll trudge it on foot with umbrella and "bowler,"—

My STELLA thinks more of a man than his dress.

I can buy her some bonbons or gloves to console her.

Though I'm rigged like a navvy, she'll love me no less.

Let the showers pour down, I am dressed to defy them—

Bad luck to the rain, why, it's passing away!

The streets are quite gay with the sunshine to dry them.

Well, there, I give up, and retire for the day!

NOTICE.—Rejected Communications or Contributions, whether MS., Printed Matter, Drawings, or Pictures of any description, will in no case be returned, not even when accompanied by a Stamped and Addressed Envelope, Cover, or Wrapper. To this rule there will be no exception.