It is fitting that I should here express my indebtedness to those Williamson Valley friends who in the kindness of their hearts made this story possible.

To Mr. George A. Carter, who so generously introduced me to the scenes described in these pages, and who, on the Pot-Hook-S ranch, gave to my family one of the most delightful summers we have ever enjoyed; to Mr. J.H. Stephens and his family, who so cordially welcomed me at rodeo time; to Mr. and Mrs. Joe Contreras, for their kindly hospitality; to Mr. and Mrs. J.W. Stewart, who, while this story was first in the making, made me so much at home in the Cross-Triangle home-ranch; to Mr. J.W. Cook, my constant companion, helpful guide, patient teacher and tactful sponsor, who, with his charming wife, made his home mine; to Mr. and Mrs. Herbert N. Cook, and to the many other cattlemen and cowboys, with whom, on the range, in the rodeos, in the wild horse chase about Toohey, after outlaw cattle in Granite Basin, in the corrals and pastures, I rode and worked and lived, my gratitude is more than I can put in words. Truer friends or better companions than these great-hearted, outspoken, hardy riders, no man could have. If my story in any degree wins the approval of these, my comrades of ranch and range. I shall be proud and happy. H.B.W.

here is a land where a man, to live, must be a man. It is a land of granite and marble and porphyry and gold—and a man's strength must be as the strength of the primeval hills. It is a land of oaks and cedars and pines—and a man's mental grace must be as the grace of the untamed trees. It is a land of far-arched and unstained skies, where the wind sweeps free and untainted, and the atmosphere is the atmosphere of those places that remain as God made them—and a man's soul must be as the unstained skies, the unburdened wind, and the untainted atmosphere. It is a land of wide mesas, of wild, rolling pastures and broad, untilled, valley meadows—and a man's freedom must be that freedom which is not bounded by the fences of a too weak and timid conventionalism.

In this land every man is—by divine right—his own king; he is his own jury, his own counsel, his own judge, and—if it must be—his own executioner. And in this land where a man, to live, must be a man, a woman, if she be not a woman, must surely perish.

This is the story of a man who regained that which in his youth had been lost to him; and of how, even when he had recovered that which had been taken from him, he still paid the price of his loss. It is the story of a woman who was saved from herself; and of how she was led to hold fast to those things, the loss of which cost the man so great a price.

The story, as I have put it down here, begins at Prescott, Arizona, on the day following the annual Fourth-of-July celebration in one of those far-western years that saw the passing of the Indian and the coming of the automobile.

The man was walking along one of the few roads that lead out from the little city, through the mountain gaps and passes, to the wide, unfenced ranges, and to the lonely scattered ranches on the creeks and flats and valleys of the great open country that lies beyond.

From the fact that he was walking in that land where the distances are such that men most commonly ride, and from the many marks that environment and training leave upon us all, it was evident that the pedestrian was a stranger. He was a man in the prime of young manhood—tall and exceedingly well proportioned—and as he went forward along the dusty road he bore himself with the unconscious air of one more accustomed to crowded streets than to that rude and unpaved highway. His clothing bore the unmistakable stamp of a tailor of rank. His person was groomed with that nicety of detail that is permitted only to those who possess both means and leisure, as well as taste. It was evident, too, from his movement and bearing, that he had not sought the mile-high atmosphere of Prescott with the hope that it holds out to those in need of health. But, still, there was a something about him that suggested a lack of the manly vigor and strength that should have been his.

A student of men would have said that Nature made this man to be in physical strength and spiritual prowess, a comrade and leader of men—a man's man—a man among men. The same student, looking more closely, might have added that in some way—through some cruel trick of fortune—this man had been cheated of his birthright.

The day was still young when the stranger gained the top of the first hill where the road turns to make its steep and winding way down through scattered pines and scrub oak to the Burnt Ranch.

Behind him the little city—so picturesque in its mountain basin, with the wild, unfenced land coming down to its very dooryards—was slowly awakening after the last mad night of its celebration. The tents of the tawdry shows that had tempted the crowds with vulgar indecencies, and the booths that had sheltered the petty games of chance where loud-voiced criers had persuaded the multitude with the hope of winning a worthless bauble or a tinsel toy, were being cleared away from the borders of the plaza, the beauty of which their presence had marred. In the plaza itself—which is the heart of the town, and is usually kept with much pride and care—the bronze statue of the vigorous Rough Rider Bucky O'Neil and his spirited charger seemed pathetically out of place among the litter of colored confetti and exploded fireworks, and the refuse from various "treats" and lunches left by the celebrating citizens and their guests. The flags and bunting that from window and roof and pole and doorway had given the day its gay note of color hung faded and listless, as though, spent with their gaiety, and mutely conscious that the spirit and purpose of their gladness was past, they waited the hand that would remove them to the ash barrel and the rubbish heap.

Pausing, the man turned to look back.

For some minutes he stood as one who, while determined upon a certain course, yet hesitates—reluctant and regretful—at the beginning of his venture. Then he went on; walking with a certain reckless swing, as though, in ignorance of that land toward which he had set his face, he still resolutely turned his back upon that which lay behind. It was as though, for this man, too, the gala day, with its tinseled bravery and its confetti spirit, was of the past.

A short way down the hill the man stopped again. This time to stand half turned, with his head in a listening attitude. The sound of a vehicle approaching from the way whence he had come had reached his ear.

As the noise of wheels and hoofs grew louder a strange expression of mingled uncertainty, determination, and something very like fear came over his face. He started forward, hesitated, looked back, then turned doubtfully toward the thinly wooded mountain side. Then, with tardy decision he left the road and disappeared behind a clump of oak bushes, an instant before a team and buckboard rounded the turn and appeared in full view.

An unmistakable cattleman—grizzly-haired, square-shouldered and substantial—was driving the wild looking team. Beside him sat a motherly woman and a little boy.

As they passed the clump of bushes the near horse of the half-broken pair gave a catlike bound to the right against his tracemate. A second jump followed the first with flash-like quickness; and this time the frightened animal was accompanied by his companion, who, not knowing what it was all about, jumped on general principles. But, quick as they were, the strength of the driver's skillful arms met their weight on the reins and forced them to keep the road.

"You blamed fools"—the driver chided good-naturedly, as they plunged ahead—"been raised on a cow ranch to get scared at a calf in the brush!"

Very slowly the stranger came from behind the bushes. Cautiously he returned to the road. His fine lips curled in a curious mocking smile. But it was himself that he mocked, for there was a look in his dark eyes that gave to his naturally strong face an almost pathetic expression of self-depreciation and shame.

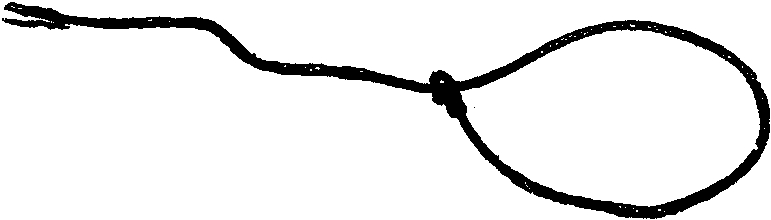

As the pedestrian crossed the creek at the Burnt Ranch, Joe Conley, leading a horse by a riata which was looped as it had fallen about the animal's neck, came through the big corral gate across the road from the house. At the barn Joe disappeared through the small door of the saddle room, the coil of the riata still in his hand, thus compelling his mount to await his return.

At sight of the cowboy the stranger again paused and stood hesitating in indecision. But as Joe reappeared from the barn with bridle, saddle blanket and saddle in hand, the man went reluctantly forward as though prompted by some necessity.

"Good morning!" said the stranger, courteously, and his voice was the voice that fitted his dress and bearing, while his face was now the carefully schooled countenance of a man world-trained and well-poised.

With a quick estimating glance Joe returned the stranger's greeting and, dropping the saddle and blanket on the ground, approached his horse's head. Instantly the animal sprang back, with head high and eyes defiant; but there was no escape, for the rawhide riata was still securely held by his master. There was a short, sharp scuffle that sent the gravel by the roadside flying—the controlling bit was between the reluctant teeth—and the cowboy, who had silently taken the horse's objection as a matter of course, adjusted the blanket, and with the easy skill of long practice swung the heavy saddle to its place.

As the cowboy caught the dangling cinch, and with a deft hand tucked the latigo strap through the ring and drew it tight, there was a look of almost pathetic wistfulness on the watching stranger's face—a look of wistfulness and admiration and envy.

Dropping the stirrup, Joe again faced the stranger, this time inquiringly, with that bold, straightforward look so characteristic of his kind.

And now, when the man spoke, his voice had a curious note, as if the speaker had lost a little of his poise. It was almost a note of apology, and again in his eyes there was that pitiful look of self-depreciation and shame.

"Pardon me," he said, "but will you tell me, please, am I right that this is the road to the Williamson Valley?"

The stranger's manner and voice were in such contrast to his general appearance that the cowboy frankly looked his wonder as he answered courteously, "Yes, sir."

"And it will take me direct to the Cross-Triangle Ranch?"

"If you keep straight ahead across the valley, it will. If you take the right-hand fork on the ridge above the goat ranch, it will take you to Simmons. There's a road from Simmons to the Cross-Triangle on the far side of the valley, though. You can see the valley and the Cross-Triangle home ranch from the top of the Divide."

"Thank you."

The stranger was turning to go when the man in the blue jumper and fringed leather chaps spoke again, curiously.

"The Dean with Stella and Little Billy passed in the buckboard less than an hour ago, on their way home from the celebration. Funny they didn't pick you up, if you're goin' there!"

The other paused questioningly. "The Dean?"

The cowboy smiled. "Mr. Baldwin, the owner of the Cross-Triangle, you know."

"Oh!" The stranger was clearly embarrassed. Perhaps he was thinking of that clump of bushes on the mountain side.

Joe, loosing his riata from the horse's neck, and coiling it carefully, considered a moment. Then: "You ain't goin' to walk to the Cross-Triangle, be you?"

That self-mocking smile touched the man's lips; but there was a hint of decisive purpose in his voice as he answered, "Oh, yes."

Again the cowboy frankly measured the stranger. Then he moved toward the corral gate, the coiled riata in one hand, the bridle rein in the other. "I'll catch up a horse for you," he said in a matter-of-fact tone, as if reaching a decision.

The other spoke hastily. "No, no, please don't trouble."

Joe paused curiously. "Any friend of Mr. Baldwin's is welcome to anything on the Burnt Ranch, Stranger."

"But I—ah—I—have never met Mr. Baldwin," explained the other lamely.

"Oh, that's all right," returned the cowboy heartily. "You're a-goin' to, an' that's the same thing." Again he started toward the gate.

"But I—pardon me—you are very kind—but I—I prefer to walk."

Once more Joe halted, a puzzled expression on his tanned and weather-beaten face. "I suppose you know it's some walk," he suggested doubtfully, as if the man's ignorance were the only possible solution of his unheard-of assertion.

"So I understand. But it will be good for me. Really, I prefer to walk."

Without a word the cowboy turned back to his horse, and proceeded methodically to tie the coiled riata in its place on the saddle. Then, without a glance toward the stranger who stood watching him in embarrassed silence, he threw the bridle reins over his horse's head, gripped the saddle horn and swung to his seat, reining his horse away from the man beside the road.

The stranger, thus abruptly dismissed, moved hurriedly away.

Half way to the creek the cowboy checked his horse and looked back at the pedestrian as the latter was making his way under the pines and up the hill. When the man had disappeared over the crest of the hill, the cowboy muttered a bewildered something, and, touching his horse with the spurs, loped away, as if dismissing a problem too complex for his simple mind.

All that day the stranger followed the dusty, unfenced road. Over his head the wide, bright sky was without a cloud to break its vast expanse. On the great, open range of mountain, flat and valley the cattle lay quietly in the shade of oak or walnut or cedar, or, with slow, listless movement, sought the watering places to slake their thirst. The wild things retreated to their secret hiding places in rocky den and leafy thicket to await the cool of the evening hunting hour. The very air was motionless, as if the never-tired wind itself drowsed indolently.

And alone in the hushed bigness of that land the man walked with his thoughts—brooding, perhaps, over whatever it was that had so strangely placed him there—dreaming, it may be, over that which might have been, or that which yet might be—viewing with questioning, wondering, half-fearful eyes the mighty, untamed scenes that met his eye on every hand. Nor did anyone see him, for at every sound of approaching horse or vehicle he went aside from the highway to hide in the bushes or behind convenient rocks. And always when he came from his hiding place to resume his journey that odd smile of self-mockery was on his face.

At noon he rested for a little beside the road while he ate a meager sandwich that he took from the pocket of his coat. Then he pushed on again, with grim determination, deeper and deeper into the heart and life of that world which was, to him, so evidently new and strange. The afternoon was well spent when he made his way—wearily now, with drooping shoulders and dragging step—up the long slope of the Divide that marks the eastern boundary of the range about Williamson Valley.

At the summit, where the road turns sharply around a shoulder of the mountain and begins the steep descent on the other side of the ridge, he stopped. His tired form straightened. His face lighted with a look of wondering awe, and an involuntary exclamation came from his lips as his unaccustomed eyes swept the wide view that lay from his feet unrolled before him.

Under that sky, so unmatched in its clearness and depth of color, the land lay in all its variety of valley and forest and mesa and mountain—a scene unrivaled in the magnificence and grandeur of its beauty. Miles upon miles in the distance, across those primeval reaches, the faint blue peaks and domes and ridges of the mountains ranked—an uncounted sentinel host. The darker masses of the timbered hillsides, with the varying shades of pine and cedar, the lighter tints of oak brush and chaparral, the dun tones of the open grass lands, and the brighter note of the valley meadows' green were defined, blended and harmonized by the overlying haze with a delicacy exquisite beyond all human power to picture. And in the nearer distances, chief of that army of mountain peaks, and master of the many miles that lie within their circle, Granite Mountain, gray and grim, reared its mighty bulk of cliff and crag as if in supreme defiance of the changing years or the hand of humankind.

In the heart of that beautiful land upon which, from the summit of the Divide, the stranger looked with such rapt appreciation, lies Williamson Valley, a natural meadow of lush, dark green, native grass. And, had the man's eyes been trained to such distances, he might have distinguished in the blue haze the red roofs of the buildings of the Cross-Triangle Ranch.

For some time the man stood there, a lonely figure against the sky, peculiarly out of place in his careful garb of the cities. The schooled indifference of his face was broken. His self-depreciation and mockery were forgotten. His dark eyes glowed with the fire of excited anticipation—with hope and determined purpose. Then, with a quick movement, as though some ghost of the past had touched him on the shoulder, he looked back on the way he had come. And the light in his eyes went out in the gloom of painful memories. His countenance, unguarded because of his day of loneliness, grew dark with sadness and shame. It was as though he looked beyond the town he had left that morning, with its litter and refuse of yesterday's pleasure, to a life and a world of tawdry shams, wherein men give themselves to win by means fair or foul the tinsel baubles that are offered in the world's petty games of chance.

And yet, even as he looked back, there was in the man's face as much of longing as of regret. He seemed as one who, realizing that he had reached a point in his life journey—a divide, as it were—from which he could see two ways, was resolved to turn from the path he longed to follow and to take the road that appealed to him the least. As one enlisting to fight in a just and worthy cause might pause a moment, before taking the oath of service, to regret the ease and freedom he was about to surrender, so this man paused on the summit of the Divide.

Slowly, at last, in weariness of body and spirit, he stumbled a few feet aside from the road, and, sinking down upon a convenient rock, gave himself again to the contemplation of that scene which lay before him. And there was that in his movement now that seemed to tell of one who, in the grip of some bitter and disappointing experience, was yet being forced by something deep in his being to reach out in the strength of his manhood to take that which he had been denied.

Again the man's untrained eyes had failed to note that which would have first attracted the attention of one schooled in the land that lay about him. He had not seen a tiny moving speck on the road over which he had passed. A horseman was riding toward him.

ad the man on the Divide noticed the approaching horseman it would have been evident, even to one so unacquainted with the country as the stranger, that the rider belonged to that land of riders. While still at a distance too great for the eye to distinguish the details of fringed leather chaps, soft shirt, short jumper, sombrero, spurs and riata, no one could have mistaken the ease and grace of the cowboy who seemed so literally a part of his horse. His seat in the saddle was so secure, so easy, and his bearing so unaffected and natural, that every movement of the powerful animal he rode expressed itself rhythmically in his own lithe and sinewy body.

While the stranger sat wrapped in meditative thought, unheeding the approach of the rider, the horseman, coming on with a long, swinging lope, watched the motionless figure on the summit of the Divide with careful interest. As he drew nearer the cowboy pulled his horse down to a walk, and from under his broad hat brim regarded the stranger intently. He was within a few yards of the point where the man sat when the latter caught the sound of the horse's feet, and, with a quick, startled look over his shoulder, sprang up and started as if to escape. But it was too late, and, as though on second thought, he whirled about with a half defiant air to face the intruder.

The horseman stopped. He had not missed the significance of that hurried movement, and his right hand rested carelessly on his leather clad thigh, while his grey eyes were fixed boldly, inquiringly, almost challengingly, on the man he had so unintentionally surprised.

As he sat there on his horse, so alert, so ready, in his cowboy garb and trappings, against the background of Granite Mountain, with all its rugged, primeval strength, the rider made a striking picture of virile manhood. Of some years less than thirty, he was, perhaps, neither as tall nor as heavy as the stranger; but in spite of a certain boyish look on his smooth-shaven, deeply-bronzed face, he bore himself with the unmistakable air of a matured and self-reliant man. Every nerve and fiber of him seemed alive with that vital energy which is the true beauty and the glory of life.

The two men presented a striking contrast. Without question one was the proud and finished product of our most advanced civilization. It was as evident that the splendid manhood of the other had never been dwarfed by the weakening atmosphere of an over-cultured, too conventional and too complex environment. The stranger with his carefully tailored clothing and his man-of-the-world face and bearing was as unlike this rider of the unfenced lands as a daintily groomed thoroughbred from the sheltered and guarded stables of fashion is unlike a wild, untamed stallion from the hills and ranges about Granite Mountain. Yet, unlike as they were, there was a something that marked them as kin. The man of the ranges and the man of the cities were, deep beneath the surface of their beings, as like as the spirited thoroughbred and the unbroken wild horse. The cowboy was all that the stranger might have been. The stranger was all that the cowboy, under like conditions, would have been.

As they silently faced each other it seemed for a moment that each instinctively recognized this kinship. Then into the dark eyes of the stranger—as when he had watched the cowboy at the Burnt Ranch—there came that look of wistful admiration and envy.

And at this, as if the man had somehow made himself known, the horseman relaxed his attitude of tense readiness. The hand that had held the bridle rein to command instant action of his horse, and the hand that had rested so near the rider's hip, came together on the saddle horn in careless ease, while a boyish smile of amusement broke over the young man's face.

That smile brought a flash of resentment into the eyes of the other and a flush of red darkened his untanned cheeks. A moment he stood; then with an air of haughty rebuke he deliberately turned his back, and, seating himself again, looked away over the landscape.

But the smiling cowboy did not move. For a moment as he regarded the stranger his shoulders shook with silent, contemptuous laughter; then his face became grave, and he looked a little ashamed. The minutes passed, and still he sat there, quietly waiting.

Presently, as if yielding to the persistent, silent presence of the horseman, and submitting reluctantly to the intrusion, the other turned, and again the two who were so like and yet so unlike faced each other.

It was the stranger now who smiled. But it was a smile that caused the cowboy to become on the instant kindly considerate. Perhaps he remembered one of the Dean's favorite sayings: "Keep your eye on the man who laughs when he's hurt."

"Good evening!" said the stranger doubtfully, but with a hint of conscious superiority in his manner.

"Howdy!" returned the cowboy heartily, and in his deep voice was the kindliness that made him so loved by all who knew him. "Been having some trouble?"

"If I have, it is my own, sir," retorted the other coldly.

"Sure," returned the horseman gently, "and you're welcome to it. Every man has all he needs of his own, I reckon. But I didn't mean it that way; I meant your horse."

The stranger looked at him questioningly. "Beg pardon?" he said.

"What?"

"I do not understand."

"Your horse—where is your horse?"

"Oh, yes! Certainly—of course—my horse—how stupid of me!" The tone of the man's answer was one of half apology, and he was smiling whimsically now as if at his own predicament, as he continued. "I have no horse. Really, you know, I wouldn't know what to do with one if I had it."

"You don't mean to say that you drifted all the way out here from Prescott on foot!" exclaimed the astonished cowboy.

The man on the ground looked up at the horseman, and in a droll tone that made the rider his friend, said, while he stretched his long legs painfully: "I like to walk. You see I—ah—fancied it would be good for me, don't you know."

The cowboy laughingly considered—trying, as he said afterward, to figure it out. It was clear that this tall stranger was not in search of health, nor did he show any of the distinguishing marks of the tourist. He certainly appeared to be a man of means. He could not be looking for work. He did not seem a suspicious character—quite the contrary—and yet—there was that significant hurried movement as if to escape when the horseman had surprised him. The etiquette of the country forbade a direct question, but—

"Yes," he agreed thoughtfully, "walking comes in handy sometimes. I don't take to it much myself, though." Then he added shrewdly, "You were at the celebration, I reckon."

The stranger's voice betrayed quick enthusiasm, but that odd wistfulness crept into his eyes again and he seemed to lose a little of his poise.

"Indeed I was," he said. "I never saw anything to compare with it. I've seen all kinds of athletic sports and contests and exhibitions, with circus performances and riding, and that sort of thing, you know, and I've read about such things, of course, but"—and his voice grew thoughtful—"that men ever actually did them—and all in the day's work, as you may say—I—I never dreamed that there were men like that in these days."

The cowboy shifted his weight uneasily in the saddle, while he regarded the man on the ground curiously. "She was sure a humdinger of a celebration," he admitted, "but as for the show part I've seen things happen when nobody was thinking anything about it that would make those stunts at Prescott look funny. The horse racing was pretty good, though," he finished, with suggestive emphasis.

The other did not miss the point of the suggestion. "I didn't bet on anything," he laughed.

"It's funny nobody picked you up on the road out here," the cowboy next offered pointedly. "The folks started home early this morning—and Jim Reid and his family passed me about an hour ago—they were in an automobile. The Simmons stage must have caught up with you somewhere."

The stranger's face flushed, and he seemed trying to find some answer.

The cowboy watched him curiously; then in a musing tone added the suggestion, "Some lonesome up here on foot."

"But there are times, you know," returned the other desperately, "when a man prefers to be alone."

The cowboy straightened in his saddle and lifted his reins. "Thanks," he said dryly, "I reckon I'd better be moving."

But the other spoke quickly. "I beg your pardon, Mr. Acton, I did not mean that for you."

The horseman dropped his hands again to the saddle horn, and resumed his lounging posture, thus tacitly accepting the apology. "You have the advantage of me," he said.

The stranger laughed. "Everyone knows that 'Wild Horse Phil' of the Cross-Triangle Ranch won the bronco-riding championship yesterday. I saw you ride."

Philip Acton's face showed boyish embarrassment.

The other continued, with his strange enthusiasm. "It was great work—wonderful! I never saw anything like it."

There was no mistaking the genuineness of his admiration, nor could he hide that wistful look in his eyes.

"Shucks!" said the cowboy uneasily. "I could pick a dozen of the boys in that outfit who can ride all around me. It was just my luck, that's all—I happened to draw an easy one."

"Easy!" ejaculated the stranger, seeing again in his mind the fighting, plunging, maddened, outlawed brute that this boy-faced man had mastered. "And I suppose catching and throwing those steers was easy, too?"

The cowboy was plainly wondering at the man's peculiar enthusiasm for these most commonplace things. "The roping? Why, that was no more than we're doing all the time."

"I don't mean the roping," returned the other, "I mean when you rode up beside one of those steers that was running at full speed, and caught him by the horns with your bare hands, and jumped from your saddle, and threw the beast over you, and then lay there with his horns pinning you down! You aren't doing that all the time, are you? You don't mean to tell me that such things as that are a part of your everyday work!"

"Oh, the bull doggin'! Why, no," admitted Phil, with an embarrassed laugh, "that was just fun, you know."

The stranger stared at him, speechless. Fun! In the name of all that is most modern in civilization, what manner of men were these who did such things in fun! If this was their recreation, what must their work be!

"Do you mind my asking," he said wistfully, "how you learned to do such things?"

"Why, I don't know—we just do them, I reckon."

"And could anyone learn to ride as you ride, do you think?" The question came with marked eagerness.

"I don't see why not," answered the cowboy honestly.

The stranger shook his head doubtfully and looked away over the wild land where the shadows of the late afternoon were lengthening.

"Where are you going to stop to-night?" Phil Acton asked suddenly.

The stranger did not take his eyes from the view that seemed to hold for him such peculiar interest. "Really," he answered indifferently, "I had not thought of that."

"I should think you'd be thinking of it along about supper time, if you've walked from town since morning."

The stranger looked up with sudden interest; but the cowboy fancied that there was a touch of bitterness under the droll tone of his reply. "Do you know, Mr. Acton, I have never been really hungry in my life. It might be interesting to try it once, don't you think?"

Phil Acton laughed, as he returned, "It might be interesting, all right, but I think I better tell you, just the same, that there's a ranch down yonder in the timber. It's nothing but a goat ranch, but I reckon they would take you in. It's too far to the Cross-Triangle for me to ask you there. You can see the buildings, though, from here."

The stranger sprang up in quick interest. "You can? The Cross-Triangle Ranch?"

"Sure," the cowboy smiled and pointed into the distance. "Those red spots over there are the roofs. Jim Reid's place—the Pot-Hook-S—is just this side of the meadows, and a little to the south. The old Acton homestead—where I was born—is in that bunch of cottonwoods, across the wash from the Cross-Triangle."

But strive as he might the stranger's eyes could discern no sign of human habitation in those vast reaches that lay before him.

"If you are ever over that way, drop in," said Phil cordially. "Mr. Baldwin will be glad to meet you."

"Do you really mean that?" questioned the other doubtfully.

"We don't say such things in this country if we don't mean them, Stranger," was the cool retort.

"Of course, I beg your pardon, Mr. Acton," came the confused reply. "I should like to see the ranch. I may—I will—That is, if I—" He stopped as if not knowing how to finish, and with a gesture of hopelessness turned away to stand silently looking back toward the town, while his face was dark with painful memories, and his lips curved in that mirthless, self-mocking smile.

And Philip Acton, seeing, felt suddenly that he had rudely intruded upon the privacy of one who had sought the solitude of that lonely place to hide the hurt of some bitter experience. A certain native gentleness made the man of the ranges understand that this stranger was face to face with some crisis in his life—that he was passing through one of those trials through which a man must pass alone. Had it been possible the cowboy would have apologized. But that would have been an added unkindness. Lifting the reins and sitting erect in the saddle, he said indifferently, "Well, I must be moving. I take a short cut here. So long! Better make it on down to the goat ranch—it's not far."

He touched his horse with the spur and the animal sprang away.

"Good-bye!" called the stranger, and that wistful look was in his eyes as the rider swung his horse aside from the road, plunged down the mountain side, and dashed away through the brush and over the rocks with reckless speed. With a low exclamation of wondering admiration, the man climbed hastily to a higher point, and from there watched until horse and rider, taking a steeper declivity without checking their breakneck course, dropped from sight in a cloud of dust. The faint sound of the sliding rocks and gravel dislodged by the flying feet died away; the cloud of dust dissolved in the thin air. The stranger looked away into the blue distance in another vain attempt to see the red spots that marked the Cross-Triangle Ranch.

Slowly the man returned to his seat on the rock. The long shadows of Granite Mountain crept out from the base of the cliffs farther and farther over the country below. The blue of the distant hills changed to mauve with deeper masses of purple in the shadows where the canyons are. The lonely figure on the summit of the Divide did not move.

The sun hid itself behind the line of mountains, and the blue of the sky in the west changed slowly to gold against which the peaks and domes and points were silhouetted as if cut by a graver's tool, and the bold cliffs and battlements of old Granite grew coldly gray in the gloom. As the night came on and the details of its structure were lost, the mountain, to the watching man on the Divide, assumed the appearance of a mighty fortress—a fortress, he thought, to which a generation of men might retreat from a civilization that threatened them with destruction; and once more the man faced back the way he had come.

The far-away cities were already in the blaze of their own artificial lights—lights valued not for their power to make men see, but for their power to dazzle, attract and intoxicate—lights that permitted no kindly dusk at eventide wherein a man might rest from his day's work—a quiet hour; lights that revealed squalid shame and tinsel show—lights that hid the stars. The man on the Divide lifted his face to the stars that now in the wide-arched sky were gathering in such unnumbered multitudes to keep their sentinel watch over the world below.

The cool evening wind came whispering over the lonely land, and all the furred and winged creatures of the night stole from their dark hiding places into the gloom which is the beginning of their day. A coyote crept stealthily past in the dark and from the mountain side below came the weird, ghostly call of its mate. An owl drifted by on silent wings. Night birds chirped in the chaparral. A fox barked on the ridge above. The shadowy form of a bat flitted here and there. From somewhere in the distance a bull bellowed his deep-voiced challenge.

Suddenly the man on the summit of the Divide sprang to his feet and, with a gesture that had he not been so alone might have seemed affectedly dramatic, stretched out his arms in an attitude of wistful longing while his lips moved as if, again and again, he whispered a name.

n the Williamson Valley country the spring round-up, or "rodeo," as it is called in Arizona, and the shipping are well over by the last of June. During the long summer weeks, until the beginning of the fall rodeo in September, there is little for the riders to do. The cattle roam free on the open ranges, while calves grow into yearlings, yearlings become two-year-olds, and two-year-olds mature for the market. On the Cross-Triangle and similar ranches, three or four of the steadier year-round hands only are held. These repair and build fences, visit the watering places, brand an occasional calf that somehow has managed to escape the dragnet of the rodeo, and with "dope bottle" ever at hand doctor such animals as are afflicted with screwworms. It is during these weeks, too, that the horses are broken; for, with the hard and dangerous work of the fall and spring months, there is always need for fresh mounts.

The horses of the Cross-Triangle were never permitted to run on the open range. Because the leaders of the numerous bands of wild horses that roamed over the country about Granite Mountain were always ambitious to gain recruits for their harems from their civilized neighbors, the freedom of the ranch horses was limited by the fences of a four-thousand-acre pasture. But within these miles of barbed wire boundaries the brood mares with their growing progeny lived as free and untamed as their wild cousins on the unfenced lands about them. The colts, except for one painful experience, when they were roped and branded, from the day of their birth until they were ready to be broken were never handled.

On the morning following his meeting with the stranger on the Divide Phil Acton, with two of his cowboy helpers, rode out to the big pasture to bring in the band.

The owner of the Cross-Triangle always declared that Phil was intimately acquainted with every individual horse and head of stock between the Divide and Camp Wood Mountain, and from Skull Valley to the Big Chino. In moments of enthusiasm the Dean even maintained stoutly that his young foreman knew as well every coyote, fox, badger, deer, antelope, mountain lion, bobcat and wild horse that had home or hunting ground in the country over which the lad had ridden since his babyhood. Certain it is that "Wild Horse Phil," as he was called by admiring friends—for reasons which you shall hear—loved this work and life to which he was born. Every feature of that wild land, from lonely mountain peak to hidden canyon spring, was as familiar to him as the streets and buildings of a man's home city are well known to the one reared among them. And as he rode that morning with his comrades to the day's work the young man felt keenly the call of the primitive, unspoiled life that throbbed with such vital strength about him. He could not have put that which he felt into words; he was not even conscious of the forces that so moved him; he only knew that he was glad.

The days of the celebration at Prescott had been enjoyable days. To meet old friends and comrades; to ride with them in the contests that all true men of his kind love; to compare experiences and exchange news and gossip with widely separated neighbors—had been a pleasure. But the curious crowds of strangers; the throngs of sightseers from the, to him, unknown world of cities, who had regarded him as they might have viewed some rare and little-known creature in a menagerie, and the brazen presence of those unclean parasites and harpies that prey always upon such occasions had oppressed and disgusted him until he was glad to escape again to the clean freedom, the pure vitality and the unspoiled spirit of his everyday life and environment. In an overflow of sheer physical and spiritual energy he lifted his horse into a run and with a shrill cowboy yell challenged his companions to a wild race to the pasture gate.

It was some time after noon when Phil checked his horse near the ruins of an old Indian lookout on the top of Black Hill. Below, in the open land above Deep Wash, he could see his cowboy companions working the band of horses that had been gathered slowly toward the narrow pass that at the eastern end of Black Hill leads through to the flats at the upper end of the big meadows, and so to the gate and to the way they would follow to the corral. It was Phil's purpose to ride across Black Hill down the western and northern slope, through the cedar timber, and, picking up any horses that might be ranging there, join the others at the gate. In the meanwhile there was time for a few minutes rest. Dismounting, he loosed the girths and lifted saddle and blanket from Hobson's steaming back. Then, while the good horse, wearied with the hard riding and the steep climb up the mountain side, stood quietly in the shade of a cedar his master, stretched on the ground near by, idly scanned the world that lay below and about them.

Very clearly in that light atmosphere Phil could see the trees and buildings of the home ranch, and, just across the sandy wash from the Cross-Triangle, the grove of cottonwoods and walnuts that hid the little old house where he was born. A mile away, on the eastern side of the great valley meadows, he could see the home buildings of the Reid ranch—the Pot-Hook-S—where Kitty Reid had lived all the days of her life except those three years which she had spent at school in the East.

The young man on the top of Black Hill looked long at the Reid home. In his mind he could see Kitty dressed in some cool, simple gown, fresh and dainty after the morning's housework, sitting with book or sewing on the front porch. The porch was on the other side of the house, it is true, and the distance was too great for him to distinguish a person in any case, but all that made no difference to Phil's vision—he could see her just the same.

Kitty had been very kind to Phil at the celebration. But Kitty was always kind—nearly always. But in spite of her kindness the cowboy felt that she had not, somehow, seemed to place a very high valuation upon the medal he had won in the bronco-riding contest. Phil himself did not greatly value the medal; but he had wanted greatly to win that championship because of the very substantial money prize that went with it. That money, in Phil's mind, was to play a very important part in a long cherished dream that was one of the things that Phil Acton did not talk about. He had not, in fact, ridden for the championship at all, but for his dream, and that was why it mattered so much when Kitty seemed so to lack interest in his success.

As though his subconscious mind directed the movement, the young man looked away from Kitty's home to the distant mountain ridge where the night before on the summit of the Divide he had met the stranger. All the way home the cowboy had wondered about the man; evolving many theories, inventing many things to account for his presence, alone and on foot, so far from the surroundings to which he was so clearly accustomed. Of one thing Phil was sure—the man was in trouble—deep trouble. The more that the clean-minded, gentle-hearted lad of the great out-of-doors thought about it, the more strongly he felt that he had unwittingly intruded at a moment that was sacred to the stranger—sacred because the man was fighting one of those battles that every man must fight—and fight alone. It was this feeling that had kept the young man from speaking of the incident to anyone—even to the Dean, or to "Mother," as he called Mrs. Baldwin. Perhaps, too, this feeling was the real reason for Phil's sense of kinship with the stranger, for the cowboy himself had moments in his life that he could permit no man to look upon. But in his thinking of the man whose personality had so impressed him one thing stood out above all the rest—the stranger clearly belonged to that world of which, from experience, the young foreman of the Cross-Triangle knew nothing. Phil Acton had no desire for the world to which the stranger belonged, but in his heart there was a troublesome question. If—if he himself were more like the man whom he had met on the Divide; if—if he knew more of that other world; if he, in some degree, belonged to that other world, as Kitty, because of her three years in school belonged, would it make any difference?

From the distant mountain ridge that marks the eastern limits of the Williamson Valley country, and thus, in a degree, marked the limit of Phil's world, the lad's gaze turned again to the scene immediately before him.

The band of horses, followed by the cowboys, were trotting from the narrow pass out into the open flats. Some of the band—the mothers—went quietly, knowing from past experience that they would in a few hours be returned to their freedom. Others—the colts and yearlings—bewildered, curious and fearful, followed their mothers without protest. But those who in many a friendly race or primitive battle had proved their growing years seemed to sense a coming crisis in their lives, hitherto peaceful. And these, as though warned by that strange instinct which guards all wild things, and realizing that the open ground between the pass and the gate presented their last opportunity, made final desperate efforts to escape. With sudden dashes, dodging and doubling, they tried again and again for freedom. But always between them and the haunts they loved there was a persistent horseman. Running, leaping, whirling, in their efforts to be everywhere at once, the riders worked their charges toward the gate.

The man on the hilltop sprang to his feet. Hobson threw up his head, and with sharp ears forward eagerly watched the game he knew so well. With a quickness incredible to the uninitiated, Phil threw blanket and saddle to place. As he drew the cinch tight, a shrill cowboy yell came up from the flat below.

One of the band, a powerful bay, had broken past the guarding horsemen, and was running with every ounce of his strength for the timber on the western slope of Black Hill. For a hundred yards one of the riders had tried to overtake and turn the fugitive; but as he saw how the stride of the free horse was widening the distance between them, the cowboy turned back lest others follow the successful runaway's example. The yell was to inform Phil of the situation.

Before the echoes of the signal could die away Phil was in the saddle, and with an answering shout sent Hobson down the rough mountain side in a wild, reckless, plunging run to head the, for the moment, victorious bay. An hour later the foreman rejoined his companions who were holding the band of horses at the gate. The big bay, reluctant, protesting, twisting and turning in vain attempts to outmaneuver Hobson, was a captive in the loop of "Wild Horse Phil's" riata.

In the big corral that afternoon Phil and his helpers with the Dean and Little Billy looking on, cut out from the herd the horses selected to be broken. These, one by one, were forced through the gate into the adjoining corral, from which they watched with uneasy wonder and many excited and ineffectual attempts to follow, when their more fortunate companions were driven again to the big pasture. Then Phil opened another gate, and the little band dashed wildly through, to find themselves in the small meadow pasture where they would pass the last night before the one great battle of their lives—a battle that would be for them a dividing point between those years of ease and freedom which had been theirs from birth and the years of hard and useful service that were to come.

Phil sat on his horse at the gate watching with critical eye as the unbroken animals raced away. "Some good ones in the bunch this year, Uncle Will," he commented to his employer, who, standing on the watering trough in the other corral, was looking over the fence.

"There's bound to be some good ones in every bunch," returned Mr. Baldwin. "And some no account ones, too," he added, as his foreman dismounted beside him.

Then, while the young man slipped the bridle from his horse and stood waiting for the animal to drink, the older man regarded him silently, as though in his own mind the Dean's observation bore somewhat upon Phil himself. That was always the way with the Dean. As Sheriff Fellows once remarked to Judge Powell in the old days of the cattle rustlers' glory, "Whatever Bill Baldwin says is mighty nigh always double-barreled."

There are also two sides to the Dean. Or, rather, to be accurate, there is a front and a back. The back—flat and straight and broad—indicates one side of his character—the side that belongs with the square chin and the blue eyes that always look at you with such frank directness. It was this side of the man that brought him barefooted and penniless to Arizona in those days long gone when he was only a boy and Arizona a strong man's country. It was this side of him that brought him triumphantly through those hard years of the Indian troubles, and in those wild and lawless times made him respected and feared by the evildoers and trusted and followed by those of his kind who, out of the hardships and dangers of those turbulent days, made the Arizona of to-day. It was this side, too, that finally made the barefoot, penniless boy the owner of the Cross-Triangle Ranch.

I do not know the exact number of the Dean's years—I only know that his hair is grey, and that he does not ride as much as he once did. I have heard him say, though, that for thirty-five years he lived in the saddle, and that the Cross-Triangle brand is one of the oldest irons in the State. And I know, too, that his back is still flat and broad and straight.

The Dean's front, so well-rounded and hearty, indicates as clearly the other side of his character. And it is this side that belongs to the full red cheeks, the ever-ready chuckle or laugh; that puts the twinkle in the blue eyes, and the kindly tones in his deep voice. It is this side of the Dean's character that adds so large a measure of love to the respect and confidence accorded him by neighbors and friends, business associates and employees. It is this side of the Dean, too, that, in these days, sits in the shade of the big walnut trees—planted by his own hand—and talks to the youngsters of the days that are gone, and that makes the young riders of this generation seek him out for counsel and sympathy and help.

Three things the Dean knows—cattle and horses and men. One thing the Dean will not, cannot tolerate—weakness in one who should be strong. Even bad men he admires, if they are strong—not for their badness, but for their strength. Mistaken men he loves in spite of their mistakes—if only they be not weaklings. There is no place anywhere in the Dean's philosophy of life for a weakling. I heard him tell a man once—nor shall I ever forget it—"You had better die like a man, sir, than live like a sneaking coyote."

The Dean's sons, men grown, were gone from the home ranch to the fields and work of their choosing. Little Billy, a nephew of seven years, was—as Mr. and Mrs. Baldwin said laughingly—their second crop.

When Phil's horse—satisfied—lifted his dripping muzzle from the watering trough, the Dean walked with his young foreman to the saddle shed. Neither of the men spoke, for between them there was that companionship which does not require a constant flow of talk to keep it alive. Not until the cowboy had turned his horse loose, and was hanging saddle and bridle on their accustomed peg did the older man speak.

"Jim Reid's goin' to begin breakin' horses next week."

"So I heard," returned Phil, carefully spreading his saddle blanket to dry.

The Dean spoke again in a tone of indifference. "He wants you to help him."

"Me! What's the matter with Jack?"

"He's goin' to the D.1 to-morrow."

Phil was examining the wrapping on his saddle horn with—the Dean noted—quite unnecessary care.

"Kitty was over this mornin'," said the Dean gently.

The young man turned, and, taking off his spurs, hung them on the saddle horn. Then as he kicked off his leather chaps he said shortly, "I'm not looking for a job as a professional bronco-buster."

The Dean's eyes twinkled. "Thought you might like to help a neighbor out; just to be neighborly, you know."

"Do you want me to ride for Reid?" demanded Phil.

"Well, I suppose as long as there's broncs to bust somebody's got to bust 'em," the Dean returned, without committing himself. And then, when Phil made no reply, he added laughing, "I told Kitty to tell him, though, that I reckoned you had as big a string as you could handle here."

As they moved away toward the house, Phil returned with significant emphasis, "When I have to ride for anybody besides you it won't be Kitty Reid's father."

And the Dean commented in his reflective tone, "It does sometimes seem to make a difference who a man rides for, don't it?"

In the pasture by the corrals, the horses that awaited the approaching trial that would mark for them the beginning of a new life passed a restless night. Some in meekness of spirit or, perhaps, with deeper wisdom fed quietly. Others wandered about aimlessly, snatching an occasional uneasy mouthful of grass, and looking about often in troubled doubt. The more rebellious ones followed the fence, searching for some place of weakness in the barbed barrier that imprisoned them. And one, who, had he not been by circumstance robbed of his birthright, would have been the strong leader of a wild band, stood often with wide nostrils and challenging eye, gazing toward the corrals and buildings as if questioning the right of those who had brought him there from the haunts he loved.

And somewhere in the night of that land which was as unknown to him as the meadow pasture was strange to the unbroken horses, a man awaited the day which, for him too, was to stand through all his remaining years as a mark between the old life and the new.

As Phil Acton lay in his bed, with doors and windows open wide to welcome the cool night air, he heard the restless horses in the near-by pasture, and smiled as he thought of the big bay and the morrow—smiled with the smile of a man who looks forward to a battle worthy of his best strength and skill.

And then, strangely enough, as he was slipping into that dreamless sleep of those who live as he lived, his mind went back again to the stranger whom he had met on the summit of the Divide. If he were more like that man, would it make any difference—the cowboy wondered.

n the beginning of the morning, when Granite Mountain's fortress-like battlements and towers loomed gray and bold and grim, the big bay horse trumpeted a warning to his less watchful mates. Instantly, with heads high and eyes wide, the band stood in frightened indecision. Two horsemen—shadowy and mysterious forms in the misty light—were riding from the corral into the pasture.

As the riders approached, individuals in the band moved uneasily, starting as if to run, hesitating, turning for another look, maneuvering to put their mates between them and the enemy. But the bay went boldly a short distance toward the danger and stood still with wide nostrils and fierce eyes as though ready for the combat.

For a few moments, as the horsemen seemed about to go past, hope beat high in the hearts of the timid prisoners. Then the riders circled to put the band between themselves and the corral gate, and the frightened animals knew. But always as they whirled and dodged in their attempts to avoid that big gate toward which they were forced to move, there was a silent, persistent horseman barring the way. The big bay alone, as though realizing the futility of such efforts and so conserving his strength for whatever was to follow, trotted proudly, boldly into the corral, where he stood, his eyes never leaving the riders, as his mates crowded and jostled about him.

"There's one in that bunch that's sure aimin' to make you ride some," said Curly Elson with a grin, to Phil, as the family sat at breakfast.

On the Cross-Triangle the men who were held through the summer and winter seasons between the months of the rodeos were considered members of the family. Chosen for their character, as well as for their knowledge of the country and their skill in their work the Dean and "Stella," as Mrs. Baldwin is called throughout all that country, always spoke of them affectionately as "our boys." And this, better than anything that could be said, is an introduction to the mistress of the Cross-Triangle household.

At the challenging laugh which followed Curly's observation, Phil returned quietly with his sunny smile, "Maybe I'll quit him before he gets good and started."

"He's sure fixin' to make you back the decision of them contest judges," offered Bob Colton.

And Mrs. Baldwin, young in spirit as any of her boys, added, "Better not wear your medal, son. It might excite him to know that you are the champion buster of Arizona."

"Shucks!" piped up Little Billy excitedly, "Phil can ride anything what wears hair, can't you, Phil?"

Phil, embarrassed at the laughter which followed, said, with tactful seriousness, to his little champion, "That's right, kid. You stand up for your pardner every time, don't you? You'll be riding them yourself before long. There's a little sorrel in that bunch that I've picked out to gentle for you." He glanced at his employer meaningly, and the Dean's face glowed with appreciation of the young man's thoughtfulness. "That old horse, Sheep, of yours," continued Phil to Little Billy, "is getting too old and stiff for your work. I've noticed him stumbling a lot lately." Again he glanced inquiringly at the Dean, who answered the look with a slight nod of approval.

"You'd better make him gentle your horse first, Billy," teased Curly. "He might not be in the business when that big one gets through with him."

Little Billy's retort came in a flash. "Huh, 'Wild Horse Phil' will be a-ridin' 'em long after you've got your'n, Curly Elson."

"Look out, son," cautioned the Dean, when the laugh had gone round again. "Curly will be slippin' a burr under your saddle, if you don't." Then to the men: "What horse is it that you boys think is goin' to be such a bad one? That big bay with the blazed face?"

The cowboys nodded.

"He's bad, all right," said Phil.

"Well," commented the Dean, leaning back in his chair and speaking generally, "he's sure got a license to be bad. His mother was the wickedest piece of horse flesh I ever knew. Remember her, Stella?"

"Indeed I do," returned Mrs. Baldwin. "She nearly ruined that Windy Jim who came from nobody knew where, and bragged that he could ride anything."

The Dean chuckled reminiscently. "She sure sent Windy back where he came from. But I tell you, boys, that kind of a horse makes the best in the world once you get 'em broke right. Horses are just like men, anyhow. If they ain't got enough in 'em to fight when they're bein' broke, they ain't generally worth breakin'."

"The man that rides that bay will sure be a-horseback," said Curly.

"He's a man's horse, all right," agreed Bob.

Breakfast over, the men left the house, not too quietly, and laughing, jesting and romping like school boys, went out to the corrals, with Little Billy tagging eagerly at their heels. The Dean and Phil remained for a few minutes at the table.

"You really oughtn't to say such things to those boys, Will," reproved Mrs. Baldwin, as she watched them from the window. "It encourages them to be wild, and land knows they don't need any encouragement."

"Shucks," returned the Dean, with that gentle note that was always in his voice when he spoke to her. "If such talk as that can hurt 'em, there ain't nothin' that could save 'em. You're always afraid somebody's goin' to go bad. Look at me and Phil here," he added, as they in turn pushed their chairs back from the table; "you've fussed enough over us to spoil a dozen men, and ain't we been a credit to you all the time?"

At this they laughed together. But as Phil was leaving the house Mrs. Baldwin stopped him at the door to say earnestly, "You will be careful to-day, won't you, son? You know my other Phil—" She stopped and turned away.

The young man knew that story—a story common to that land where the lives of men are not infrequently offered a sacrifice to the untamed strength of the life that in many forms they are daily called upon to meet and master.

"Never mind, mother," he said gently. "I'll be all right." Then more lightly he added, with his sunny smile, "If that big bay starts anything with me, I'll climb the corral fence pronto."

Quietly, as one who faces a hard day's work, Phil went to the saddle shed where he buckled on chaps and spurs. Then, after looking carefully to stirrup leathers, cinch and latigos, he went on to the corrals, the heavy saddle under his arm.

Curly and Bob, their horses saddled and ready, were making animated targets of themselves for Little Billy, who, mounted on Sheep, a gentle old cow-horse, was whirling a miniature riata. As the foreman appeared, the cowboys dropped their fun, and, mounting, took the coils of their own rawhide ropes in hand.

"Which one will you have first, Phil?" asked Curly, as he moved toward the gate between the big corral and the smaller enclosure that held the band of horses.

"That black one with the white star will do," directed Phil quietly. Then to Little Billy: "You'd better get back there out of the way, pardner. That black is liable to jump clear over you and Sheep."

"You better get outside, son," amended the Dean, who had come out to watch the beginning of the work.

"No, no—please, Uncle Will," begged the lad. "They can't get me as long as I'm on Sheep."

Phil and the Dean laughed.

"I'll look out for him," said the young man. "Only," he added to the boy, "you must keep out of the way."

"And see that you stick to Sheep, if you expect him to take care of you," finished the Dean, relenting.

Meanwhile the gate between the corrals had been thrown open, and with Bob to guard the opening Curly rode in among the unbroken horses to cut out the animal indicated by Phil, and from within that circular enclosure, where the earth had been ground to fine powder by hundreds of thousands of frightened feet, came the rolling thunder of quick-beating hoofs as in a swirling cloud of yellow dust the horses rushed and leaped and whirled. Again and again the frightened animals threw themselves against the barrier that hemmed them in; but that fence, built of cedar posts set close in stockade fashion and laced on the outside with wire, was made to withstand the maddened rush of the heaviest steers. And always, amid the confusion of the frenzied animals, the figure of the mounted man in their midst could be seen calmly directing their wildest movements, and soon, out from the crowding, jostling, whirling mass of flying feet and tossing manes and tails, the black with the white star shot toward the gate. Bob's horse leaped aside from the way. Curly's horse was between the black and his mates, and before the animal could gather his confused senses he was in the larger corral. The day's work had begun.

The black dodged skillfully, and the loop of Curly's riata missed the mark.

"You better let somebody put eyes in that rope, Curly," remarked Phil, laconically, as he stepped aside to avoid a wild rush.

The chagrined cowboy said something in a low tone, so that Little Billy could not hear.

The Dean chuckled.

Bob's riata whirled, shot out its snaky length, and his trained horse braced himself skillfully to the black's weight on the rope. For a few minutes the animal at the loop end of the riata struggled desperately—plunging, tugging, throwing himself this way and that; but always the experienced cow-horse turned with his victim and the rope was never slack. When his first wild efforts were over and the black stood with his wide braced feet, breathing heavily as that choking loop began to tell, the strain on the taut riata was lessened, and Phil went quietly toward the frightened captive.

No one moved or spoke. This was not an exhibition the success of which depended on the vicious wildness of the horse to be conquered. This was work, and it was not Phil's business to provoke the black to extremes in order to exhibit his own prowess as a rider for the pleasure of spectators who had paid to see the show. The rider was employed to win the confidence of the unbroken horse entrusted to him; to force obedience, if necessary; to gentle and train, and so make of the wild creature a useful and valuable servant for the Dean.

There are riders whose methods demand that they throw every unbroken horse given them to handle, and who gentle an animal by beating it about the head with loaded quirts, ripping its flanks open with sharp spurs and tearing its mouth with torturing bits and ropes. These turn over to their employers as their finished product horses that are broken, indeed—but broken only in spirit, with no heart or courage left to them, with dispositions ruined, and often with physical injuries from which they never recover. But riders of such methods have no place among the men employed by owners of the Dean's type. On the Cross-Triangle, and indeed on all ranches where conservative business principles are in force, the horses are handled with all the care and gentleness that the work and the individuality of the animal will permit.

After a little Phil's hand gently touched the black's head. Instantly the struggle was resumed. The rider dodged a vicious blow from the strong fore hoofs and with a good natured laugh softly chided the desperate animal. And so, presently, the kind hand was again stretched forth; and then a broad band of leather was deftly slipped over the black's frightened eyes. Another thicker and softer rope was knotted so that it could not slip about the now sweating neck, and fashioned into a hackamore or halter about the animal's nose. Then the riata was loosed. Working deftly, silently, gently—ever wary of those dangerous hoofs—Phil next placed blanket and saddle on the trembling black and drew the cinch tight. Then the gate leading from the corral to the open range was swung back. Easily, but quickly and surely, the rider swung to his seat. He paused a moment to be sure that all was right, and then leaning forward he reached over and raised the leather blindfold. For an instant the wild, unbroken horse stood still, then reared until it seemed he must fall, and then, as his forefeet touched the ground again, the spurs went home, and with a mighty leap forward the frenzied animal dashed, bucking, plunging, pitching, through the gate and away toward the open country, followed by Curly and Bob, with Little Billy spurring old Sheep, in hot pursuit.

For a little the Dean lingered in the suddenly emptied corral. Stepping up on the end of the long watering trough, close to the dividing fence, he studied with knowing eye the animals on the other side. Then leisurely he made his way out of the corral, visited the windmill pump, looked in on Stella from the kitchen porch, and then saddled Browny, his own particular horse that grazed always about the place at privileged ease, and rode off somewhere on some business of his own.

When the black horse had spent his strength in a vain attempt to rid himself of the dreadful burden that had attached itself so securely to his back, he was herded back to the corral, where the burden set him free. Dripping with sweat, trembling in every limb and muscle, wild-eyed, with distended nostrils and heaving flanks, the black crowded in among his mates again, his first lesson over—his years of ease and freedom past forever.

"And which will it be this time?" came Curly's question.

"I'll have that buckskin this trip," answered Phil.

And again that swirling cloud of dust raised by those thundering hoofs drifted over the stockade enclosure, and out of the mad confusion the buckskin dashed wildly through the gate to be initiated into his new life.

And so, hour after hour, the work went on, as horse after horse at Phil's word was cut out of the band and ridden; and every horse, according to disposition and temper and strength, was different. While his helpers did their part the rider caught a few moments rest. Always he was good natured, soft spoken and gentle. When a frightened animal, not understanding, tried to kill him, he accepted it as evidence of a commendable spirit, and, with that sunny, boyish smile, informed his pupil kindly that he was a good horse and must not make a fool of himself.

In so many ways, as the Dean had said at breakfast that morning, horses are just like men.

It was mid-afternoon when the master of the Cross-Triangle again strolled leisurely out to the corrals. Phil and his helpers, including Little Billy, were just disappearing over the rise of ground beyond the gate on the farther side of the enclosure as the Dean reached the gate that opens toward the barn and house. He went on through the corral, and slowly, as one having nothing else to do, climbed the little knoll from which he could watch the riders in the distance. When the horsemen had disappeared among the scattered cedars on the ridge, a mile or so to the west, the Dean still stood looking in that direction. But the owner of the Cross-Triangle was not watching for the return of his men. He was not even thinking of them. He was looking beyond the cedar ridge to where, several miles away, a long, mesa-topped mountain showed black against the blue of the more distant hills. The edge of this high table-land broke abruptly in a long series of vertical cliffs, the formation known to Arizonians as rim rocks. The deep shadows of the towering black wall of cliffs and the gloom of the pines and cedars that hid the foot of the mountain gave the place a sinister and threatening appearance.

As he looked, the Dean's kindly face grew somber and stern; his blue eyes were for the moment cold and accusing; under his grizzled mustache his mouth, usually so ready to smile or laugh, was set in lines of uncompromising firmness. In these quiet and well-earned restful years of the Dean's life the Tailholt Mountain outfit was the only disturbing element. But the Dean did not permit himself to be long annoyed by the thoughts provoked by Tailholt Mountain. Philosophically he turned his broad back to the intruding scene, and went back to the corral, and to the more pleasing occupation of looking at the horses.

If the Dean had not so abruptly turned his back upon the landscape, he would have noticed the figure of a man moving slowly along the road that skirted the valley meadow leading from Simmons to the Cross-Triangle Ranch.

Presently the riders returned, and Phil, when he had removed saddle, blanket and hackamore from his pupil, seated himself on the edge of the watering trough beside the Dean.

"I see you ain't tackled the big bay yet," remarked the older man.

"Thought if I'd let him look on for a while, he might figure it out that he'd better be good and not get himself hurt," smiled Phil. "He's sure some horse," he added admiringly. Then to his helpers: "I'll take that black with the white forefoot this time, Curly."

Just as the fresh horse dashed into the larger corral a man on foot appeared, coming over the rise of ground to the west; and by the time that Curly's loop was over the black's head the man stood at the gate. One glance told Phil that it was the stranger whom he had met on the Divide.

The man seemed to understand that it was no time for greetings and, without offering to enter the enclosure, climbed to the top of the big gate, where he sat, with one leg over the topmost bar, an interested spectator.

The maneuvers of the black brought Phil to that side of the corral, and, as he coolly dodged the fighting horse, he glanced up with his boyish smile and a quick nod of welcome to the man perched above him. The stranger smiled in return, but did not speak. He must have thought, though, that this cowboy appeared quite different from the picturesque rider he had seen at the celebration and on the summit of the Divide. That Phil Acton had been—as the cowboy himself would have said—"all togged out in his glad rags." This man wore chaps that were old and patched from hard service; his shirt, unbuttoned at the throat, was the color of the corral dirt, and a generous tear revealed one muscular shoulder; his hat was greasy and battered; his face grimed and streaked with dust and sweat, but his sunny, boyish smile would have identified Phil in any garb.

When the rider was ready to mount, and Bob went to open the gate, the stranger climbed down and drew a little aside. And when Phil, passing where he stood, looked laughingly down at him from the back of the bucking, plunging horse, he made as if to applaud, but checked himself and went quickly to the top of the knoll to watch the riders until they disappeared over the ridge.

"Howdy! Fine weather we're havin'." It was the Dean's hearty voice. He had gone forward courteously to greet the stranger while the latter was watching the riders.

The man turned impulsively, his face lighted with enthusiasm. "By Jove!" he exclaimed, "but that man can ride!"

"Yes, Phil does pretty well," returned the Dean indifferently. "Won the championship at Prescott the other day." Then, more heartily: "He's a mighty good boy, too—take him any way you like."

As he spoke the cattleman looked the stranger over critically, much as he would have looked at a steer or horse, noting the long limbs, the well-made body, the strong face and clear, dark eyes. The man's dress told the Dean simply that the stranger was from the city. His bearing commanded the older man's respect. The stranger's next statement, as he looked thoughtfully over the wide Land of valley and hill and mesa and mountain, convinced the Dean that he was a man of judgment.

"Arizona is a wonderful country, sir—wonderful!"

"Finest in the world, sir," agreed the Dean promptly. "There just naturally can't be any better. We've got the climate; we've got the land; and we've got the men."

The stranger looked at the Dean quickly when he said "men." It was worth much to hear the Dean speak that word.

"Indeed you have," he returned heartily. "I never saw such men."

"Of course you haven't," said the Dean. "I tell you, sir, they just don't make 'em outside of Arizona. It takes a country like this to produce real men. A man's got to be a man out here. Of course, though," he admitted kindly, "we don't know much except to ride, an' throw a rope, an' shoot, mebby, once in a while."

The riders were returning and the Dean and the stranger walked back down the little hill to the corral.

"You have a fine ranch here, Mr. Baldwin," again observed the stranger.

The Dean glanced at him sharply. Many men had tried to buy the Cross-Triangle. This man certainly appeared prosperous even though he was walking. But there was no accounting for the queer things that city men would do.

"It does pretty well," the cattleman admitted. "I manage to make a livin'."

The other smiled as though slightly embarrassed. Then: "Do you need any help?"

"Help!" The Dean looked at him amazed.

"I mean—I would like a position—to work for you, you know."

The Dean was speechless. Again he surveyed the stranger with his measuring, critical look. "You've never done any work," he said gently.

The man stood very straight before him and spoke almost defiantly. "No, I haven't, but is that any reason why I should not?"

The Dean's eyes twinkled, as they have a way of doing when you say something that he likes. "I'd say it's a better reason why you should," he returned quietly.

Then he said to Phil, who, having dismissed his four-footed pupil, was coming toward them:

"Phil, this man wants a job. Think we can use him?"

The young man looked at the stranger with unfeigned surprise and with a hint of amusement, but gave no sign that he had ever seen him before. The same natural delicacy of feeling that had prevented the cowboy from discussing the man upon whose privacy he felt he had intruded that evening of their meeting on the Divide led him now to ignore the incident—a consideration which could not but command the strange man's respect, and for which he looked his gratitude.

There was something about the stranger, too, that to Phil seemed different. This tall, well-built fellow who stood before them so self-possessed, and ready for anything, was not altogether like the uncertain, embarrassed, half-frightened and troubled gentleman at whom Phil had first laughed with thinly veiled contempt, and then had pitied. It was as though the man who sat that night alone on the Divide had, out of the very bitterness of his experience, called forth from within himself a strength of which, until then, he had been only dimly conscious. There was now, in his face and bearing, courage and decision and purpose, and with it all a glint of that same humor that had made him so bitterly mock himself. The Dean's philosophy touching the possibilities of the man who laughs when he is hurt seemed in this stranger about to be justified. Phil felt oddly, too, that the man was in a way experimenting with himself—testing himself as it were—and being altogether a normal human, the cowboy felt strongly inclined to help the experimenter. In this spirit he answered the Dean, while looking mischievously at the stranger.

"We can use him if he can ride."

The stranger smiled understandingly. "I don't see why I couldn't," he returned in that droll tone. "I seem to have the legs." He looked down at his long lower limbs reflectively, as though quaintly considering them quite apart from himself.

Phil laughed.

"Huh," said the Dean, slightly mystified at the apparent understanding between the young men. Then to the stranger: "What do you want to work for? You don't look as though you needed to. A sort of vacation, heh?"

There was spirit in the man's answer. "I want to work for the reason that all men want work. If you do not employ me, I must try somewhere else."

"Come from Prescott to Simmons on the stage, did you?"

"No, sir, I walked."

"Walked! Huh! Tried anywhere else for a job?"

"No, sir."

"Who sent you out here?"

The stranger smiled. "I saw Mr. Acton ride in the contest. I learned that he was foreman of the Cross-Triangle Ranch. I thought I would rather work where he worked, if I could."

The Dean looked at Phil. Phil looked at the Dean. Together they looked at the stranger. The two cowboys who were sitting on their horses near-by grinned at each other.

"And what is your name, sir?" the Dean asked courteously.

For the first time the man hesitated and seemed embarrassed. He looked uneasily about with a helpless inquiring glance, as though appealing for some suggestion.