CONTENTS.

INTRODUCTION.LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

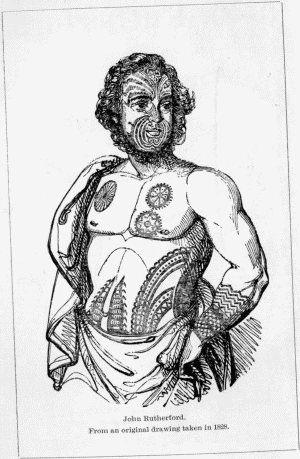

John Rutherford

Eighty years ago, when the story told in these pages was first published, "forecastle yarns" were more thrilling than they are now. In these days we look for information in regard to a new land's capabilities for pastoral, agricultural, and commercial pursuits; in those days it was customary, with a large portion of the British public, at any rate, to expect sailors to tell stories

Of the cannibals that each other eat,and to relate other particulars likely to arrest the attention and excite the imagination. Men then sailed to unknown lands, peopled by unknown barbarians, and their adventures in strange and mysterious countries were clothed in a romance which has been almost completely dispelled by the telegraph, the newspaper press, cheap books, and rapid transit, and by the utilitarian ideas which have swept over the world.

It was largely to meet the public taste for something wonderful and striking that John Rutherford's story of adventures in New Zealand saw the light of publicity. In fairness to the original editor and the publisher, however, it should be stated that the story was given also as a means of supplying interesting information in regard to a country and a race of which very little was then known. It was embodied in a book of 400 pages, entitled "The New Zealanders," published in 1830, for the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, by the famous publisher, Charles Knight.

He was a versatile, talented, and ambitious man; but all his ambitions ran in the direction of the public good. From the time of his early manhood, he wished to become a public instructor. At first he tried to achieve his end by means of journalism, which he entered in 1812, by reporting Parliamentary debates for "The Globe" and "The British Press," two London journals. Later on he started a publishing business in London. Dealing only with instructive subjects, he established "Knight's Quarterly Magazine," and other periodicals, to which he was one of the prominent contributors.

He was not a business man, and in 1828 he was overwhelmed by financial difficulties. In the meantime he had become acquainted with the brilliant but erratic Lord Brougham, who had completed arrangements for putting into operation one of his great enterprises for educating the masses. This was the establishment of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. It began a series of publications under the title of "The Library of Entertaining Knowledge," which Knight published. The first volume, written by Knight himself, was "The Menageries"; the second was "The New Zealanders." Other publications were issued by the society until it was dissolved in 1846. Knight continued to send works out of the press nearly to the end of his useful life, in March, 1873. Some of these were written by himself, some by friends, and some were translations. His "Penny Magazine," at the end of its first year, had a sale of 200,000 copies. Amongst his other publications are Lane's "Arabian Nights," "The Pictorial Bible," "The Pictorial History of England," and—the object of his highest ambition—"The Pictorial Shakespeare." In "Passages of a Working Life," he wrote his own biography. In spite of his strenuous life he died a poor man. He was an enthusiast, but his impetuous nature induced him to attempt to carry out his schemes before they had matured. He had a quick temper and an eloquent tongue. The esteem in which he was held by his friends is shown by the admirable jest with which Douglas Jerrold took leave of him one evening at a social gathering. "Good Knight," Jerrold said.

The "New Zealanders" was published anonymously, and for many years the authorship was attributed to Lord Brougham. There is no doubt now, however, that the author was George Lillie Craik, a scholar and a man of letters. He was born at Kennoway, Fife, in 1798. He studied at St. Andrew's, and went through a divinity course, but never applied to be licensed as a preacher. Like Knight, he was attracted by journalism, which he regarded as a means of instructing the public. When he was only twenty years of age he was editor of "The Star," a local newspaper. In London he adopted authorship as a profession. In 1849, he was appointed Professor of English Literature and History at the Queen's College, Belfast, and later on, although he still resided at Belfast, he became examiner for the Indian Civil Service. All his literary work is distinguished by careful research. Perhaps his best effort is represented by "The Pursuit of Knowledge Under Difficulties," published in the same year as "The New Zealanders." With a colleague he edited "The Pictorial History of England," in four volumes. Amongst his other works are "A Romance of the Peerage," "Spencer and his Poetry," "A History of Commerce," "The English of Shakespeare," and "Bacon, his Writings and Philosophy." He had a flowing and cultured style, and he embellished his work with many references to the classics. He was one of the best read men of his time. His extensive reading and the simplicity of his style made him a very welcome contributor to the "Penny Magazine," the "Penny Cyclopædia," and other popular publications. He had a paralytic stroke while lecturing in Belfast in February, 1866, and he died in June of the same year. It is said of him that he was popular with students and welcome in society.

It is not known if Craik met Rutherford. He probably did not. He may have had "The New Zealanders" partly written when the manuscript describing Rutherford's adventures was placed in his hands. In that case, he wove it into his book, using it as a means of illustrating his remarks on the Maoris' customs. His work bears the stamp of honesty and industrious care. He collected all the information dealing with New Zealand available at the time, and he produced a fairly large book, which, for many years after it was published, must have been a valuable contribution to the public's store of "entertaining knowledge."

Rutherford, as his narrative shows, was ten years amongst the Maoris. He was an ignorant sailor. He could not write, and the account of his adventures, it is explained, was dictated to a friend while he was on the voyage back to England. Craik says that if allowance is made for some grammatical solecisms, the story, as it appeared in the manuscript, was told with great clearness, and sometimes with considerable spirit. Knight evidently knew him, as it is stated in "The New Zealanders" that "the publisher of this volume had many conversations with him when he was exhibited in London." It is probable, too, that Brougham knew him. Brougham, indeed, may have "discovered" him and introduced him to Knight. Rutherford was just the kind of man in whose company Brougham delighted to spend hours. He would listen to the recital of the thrilling adventures with the Maoris with breathless interest. A story told of the madcap days of Brougham's youth gives some idea of the welcome he would extend to Rutherford. One evening, after Brougham and some other gay spirits had supped together in London, they saw a mob of idle scoundrels beating an unfortunate woman with brutal ferocity. The young fellows went to her rescue. Their interference increased the tumult, and all the watchmen in the neighbourhood were soon about their ears. In return for their chivalry they were lodged in the watch-house. Amongst their fellow-prisoners there was an old sailor, who sat cowering over the embers of the fire. He had been in the American War. Brougham picked up an acquaintance with him, and all night long the young man held the old one in conversation, ascertaining the strength of the forces in the engagements, the scenes of the battles, the nature of the manoeuvres, the advances and reverses, and so on, until his avariciousness for knowledge was satisfied.

Neither Brougham nor Knight, nor even Craik, had sufficient means of testing the accuracy of Rutherford's story. Unfortunately there are many points on which the narrative is not only inaccurate but misleading. Craik concludes that Poverty Bay, where Cook first landed in New Zealand, is the scene of the capture of the "Agnes." Rutherford, however, gives the name as "Tokomardo." This corresponds with a bay some miles further north, and about forty miles from the East Cape. The Maoris call it Tokomaru, which Rutherford evidently intended. His description of the place might represent Tokomaru almost as well as Poverty Bay. The strangest part of the affair, however, is that the Maoris on that coast have no knowledge whatever of the "Agnes," the vessel which, according to Rutherford, was captured in the bay he describes. Eighty years ago the arrival of a vessel at New Zealand was an advent of the utmost importance. The news spread throughout the land with surprising rapidity, and whole tribes flocked to the port to see the "Pakehas" and trade for their iron implements and guns. The Maoris of the district know of three white men, whom they called Riki, Punga, and Tapore, who lived amongst them for some time in the early days, before colonization began; but they have no knowledge of Rutherford. The chiefs to whom Rutherford frequently refers did not belong to that district. The chief who takes the principal part in the story, "Aimy," cannot be traced. The name is spelt wrongly, and it is difficult to supply a Maori name that the spelling in the book might represent. This is surprising, as the Maoris are very careful in regard to their genealogical records.[A] While Rutherford was in New Zealand some terrible slaughters took place in the Poverty Bay district, but he does not refer to these, although they must have been one of the principal subjects of conversation amongst the Maoris for months, perhaps years.

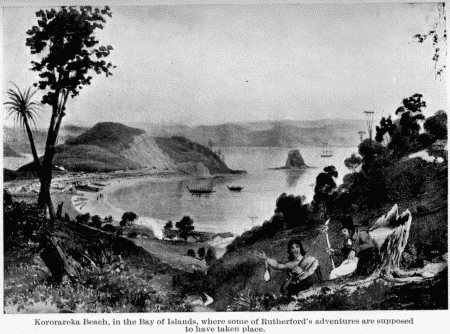

Near the end of the narrative, Rutherford gives an account of a great battle, in which the chief Hongi was a prominent figure. His description of what took place is incorrect in several respects. Victory went to Hongi, not, as Rutherford says, to the people of Kaipara and their allies, although they were victorious in the first skirmish. The battle is known as Te Ika-a-rangi-nui, that is the Great Fish of the Sky or the Milky Way, and it took place in February, 1825. As Rutherford states, Hongi was present, and wore the famous coat of mail armour which had been given to him by His Majesty King George IV. when he was in England in 1820. The strife was caused not by an attempt to steal Hongi's armour, as Rutherford suggests, but by a thirst for revenge for the death of a chief of the Nga-Puhi tribe, to which Hongi belonged. The chief Whare-umu, evidently identical with "Ewarree-hum" in Rutherford's narrative, did not belong to the party that Rutherford was connected with; he was related to the man whose murder was avenged, and seems to have been Hongi's first lieutenant. Some authorities, notably Bishop Williams, of Waiapu,[B] and Mr. Percy Smith,[C] believe that Rutherford was not present at the battle, and that he obtained all his information from others. Bishop Williams, who knows the Poverty Bay district as well as anyone, has come to the conclusion that Rutherford must have spent his years in New Zealand in the Bay of Islands district; and Mr Percy Smith, in a letter to me, says that he has always entertained the idea that Rutherford was one of the men taken when the schooner "Brothers" was attacked at Kennedy Bay in 1815. Bishop Williams sets up the theory that Rutherford was a deserter from a vessel which visited New Zealand, that he induced the Maoris to tattoo him in order that he might escape detection after he had returned to civilization, and that he concocted the story of the capture of the "Agnes" to account for his reappearance amongst Europeans. The weakness of this theory is that he evidently did not object to publicity, and that the tattooing would make him a conspicuous man who could not avoid public attention. If Bishop Williams is right in assuming that Rutherford wished to escape detection, he took the very best course to defeat his object.

Whatever Rutherford's object may have been, and whether he deceived the author and publisher of "The New Zealanders," or merely erred through ignorance and lack of observation, there is no doubt that he spent some years with the Maoris in the northern part of New Zealand. His tattooed face is sufficient evidence of that. The pattern is the Maori "moko." The tattooing on his breast, stomach, and arms, however, is not the work of Maoris; that was done, probably, by natives at some of the islands, or by sailors. I hardly think that those who read the narrative will agree with Bishop Williams's opinion that it is "a mere romance." It is more like the story of an ignorant, unobservant, careless sailor, who entertained no idea that any importance would be attached to his statements. Many mistakes were probably made in the work of dictating the narrative to a fellow-sailor. If Rutherford had been bent upon making a romantic story, he would have told it in a different form. There is no straining after effect in the manuscript reproduced by Craik. The faults are inaccuracies, not exaggerations. Some excuse may be found for Rutherford's mistakes in the description of the battle Te Ika-a-rangi-nui in the fact that modern Maori scholars cannot agree on important details, there being differences of opinion in regard to even the year in which the battle was fought.

It is felt that, with all its blemishes, the story has a good claim to be included in the list of New Zealand works that are now being reprinted by Messrs. Whitcombe and Tombs, to whom the people of New Zealand are deeply indebted. When Mr. Whitcombe first asked me to edit Rutherford's story for his firm, I proposed to take it alone, leaving out all the rest of Craik's work in "The New Zealanders." On reading the book again I came to the conclusion that many of Craik's remarks, although discursive at times, are sufficiently interesting to be read now, and I have included in the reprint a large portion of his original writings. I have retained his spelling of Maori words, but have made many corrections in footnotes. The book is not sent out as an authentic account of the Maoris. "The New Zealanders" was the first book that attempted to deal with them, and it has been superseded by many which have been written in the light of more extensive knowledge, and in them students will find results of much patient study and research.

JAMES DRUMMOND.

Christchurch,

February 13th, 1908.

FOOTNOTES:

[A]At my request, Mr. S. Percy Smith, the author of "Hawaiki, the Original Home of the Maori," endeavoured to trace "Aimy," but even his extensive knowledge of the Maori language and tribal histories failed to bring that man to light. Mr. Smith explains that "Ai" in Rutherford's spelling represents "E," a vocative, in the accepted method of spelling, and "my" represents "mai." The two words, combined, would be "E Mai." In this way, "Mai's" attention would be called. But "Mai" may be the first, second, or third syllable of a man's name, according to euphony. The name supplied in the narrative, therefore, is no guide in a search for Rutherford's friendly chief.

Transactions New Zealand Institute, volume xxiii., page 453.

"Journal of the Polynesian Society," volume x., page 35.

John Rutherford, according to his own account, was born at Manchester about the year 1796. He went to sea, he states, when he was hardly more than ten years of age, having up to that time been employed as a piecer in a cotton factory in his native town; and after that he appears to have been but little in England, or even on shore, for many years.

He served for a considerable time on board a man-of-war off the coast of Brazil; and was afterwards at the storming of San Sebastian, in August, 1813. On coming home from Spain, he entered himself on board another king's ship, bound for Madras, in which he afterwards proceeded to China by the east passage, and lay for about a year at Macao.

In the course of this voyage his ship touched at several islands in the great Indian Archipelago, among others at the Bashee Islands,[D] which have been rarely visited. On his return from the east he embarked on board a convict vessel bound for New South Wales; and afterwards made two trading voyages among the islands of the South Sea.

It was in the course of the former of these that he first saw New Zealand, the vessel having touched at the Bay of Islands, on her way home to Port Jackson.

His second trading voyage in those seas was made in the "Magnet," a three-masted schooner, commanded by Captain Vine; but this vessel having put in at Owhyhee,[E] Rutherford fell sick and was left on that island. Having recovered, however, in about a fortnight, he was taken on board the "Agnes," an American brig of six guns and fourteen men, commanded by Captain Coffin, which was then engaged in trading for pearl and tortoiseshell among the islands of the Pacific.

This vessel, after having touched at various other places, on her return from Owhyhee, approached the east coast of New Zealand, intending to put in for refreshments at the Bay of Islands.

Rutherford states in his journal that this event, which was to him of such importance, occurred on March 6th, 1816. They first came in sight of the Barrier Islands, some distance to the south of the port for which they were making. They accordingly directed their course to the north; but they had not got far on their way when it began to blow a gale from the north-east, which, being aided by a current, not only made it impossible for them to proceed to the Bay of Islands, but even carried them past the mouth of the Thames. It lasted for five days, and when it abated they found themselves some distance to the south of a high point of land, which, from Rutherford's description, there can be no doubt must have been that to which Captain Cook gave the name of East Cape. Rutherford calls it sometimes the East, and sometimes the South-East Cape, and describes it as the highest part of the coast. It lies nearly in latitude 37° 42' S.

The land directly opposite to them was indented by a large bay. This the captain was very unwilling to enter, believing that no ship had ever anchored in it before. We have little doubt, however, that this was the very bay into which Cook first put, on his arrival on the coasts of New Zealand, in the beginning of October, 1769. He called it Poverty Bay, and found it to lie in latitude 38° 42' S. The bay in which Rutherford now was must have been at least very near this part of the coast; and his description answers exactly to that which Cook gives of Poverty Bay.

It was, says Rutherford, in the form of a half-moon, with a sandy beach round it, and at its head a fresh-water river, having a bar across its mouth, which makes it navigable only for boats. He mentions also the height of the land which forms its sides. All these particulars are noticed by Cook. Even the name given to it by the natives, as reported by the one, is not so entirely unlike that stated by the other, as to make it quite improbable that the two are merely the same word differently misrepresented. Cook writes it Taoneroa, and Rutherford Takomardo. The slightest examination of the vocabularies of barbarous tongues, which have been collected by voyagers and travellers, will convince every one of the extremely imperfect manner in which the ear catches sounds to which it is unaccustomed, and of the mistakes to which this and other causes give rise, in every attempt which is made to take down the words of a language from the native pronunciation, by a person who does not understand it.

Reluctant as the captain was to enter this bay, from his ignorance of the coast, and the doubts he consequently felt as to the disposition of the inhabitants, they at last determined to stand in for it, as they had great need of water, and did not know when the wind might permit them to get to the Bay of Islands.

They came to anchor, accordingly, off the termination of a reef of rocks, immediately under some elevated land, which formed one of the sides of the bay. As soon as they had dropped anchor, a great many canoes came off to the ship from every part of the bay, each containing about thirty women, by whom it was paddled. Very few men made their appearance that day; but many of the women remained on board all night, employing themselves chiefly in stealing whatever they could lay their hands on. Their conduct greatly alarmed the captain, and a strict watch was kept during the night.

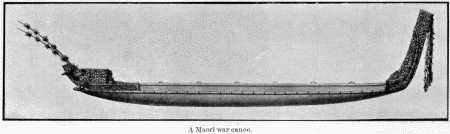

The next morning one of the chiefs came on board, whose name they were told was Aimy, in a large war-canoe, about sixty feet long, and carrying above a hundred of the natives, all provided with quantities of mats and fishing-lines, made of the strong white flax[F] of the country, with which they professed to be anxious to trade with the crew.

After this chief had been for some time on board, it was agreed that he should return to the land, with some others of his tribe, in the ship's boat, to procure a supply of water. This arrangement the captain was very anxious to make, as he was averse from allowing any of the crew to go on shore, wishing to keep them all on board for the protection of the ship.

In due time the boat returned, laden with water, which was immediately hoisted on board; and the chief and his men were despatched a second time on the same errand. Meanwhile, the rest of the natives continued to take pigs to the ship in considerable numbers; and by the close of the day about two hundred had been purchased, together with a quantity of fern-root to feed them on.

Up to this time, therefore, no hostile disposition had been manifested by the savages; and their intercourse with the ship had been carried on with every appearance of friendship and cordiality, if we except the propensity they had shown to pilfer a few of the tempting rarities exhibited to them by their civilised visitors. Their conduct as to this matter ought perhaps to be taken rather as an evidence that they had not as yet formed any design of attacking the vessel, as they would, in that case, scarcely have taken the trouble of stealing a small part of what they meant immediately to seize upon altogether. On the other hand, such an infraction of the rules of hospitality would not have accorded with that system of insidious kindness by which it is their practice to lull the suspicions of those whom they are on the watch to destroy.

During the night, however, the thieving was renewed, and carried to a more alarming extent, inasmuch as it was found in the morning that some of the natives had not only stolen the lead off the ship's stern, but had also cut away many of the ropes, and carried them off in their canoes. It was not till daybreak, too, that the chief returned with his second cargo of water; and it was then observed that the ship's boat he had taken with him leaked a great deal; on which the carpenter examined her, and found that a great many of the nails had been drawn out of her planks.

About the same time, Rutherford detected one of the natives in the act of stealing the dipson lead,—"which, when I took it from him," says he, "he grinded his teeth and shook his tomahawk at me."

"The captain," he continues, "now paid the chief for fetching the water, giving him two muskets, and a quantity of powder and shot, arms and ammunition being the only articles these people will trade for.

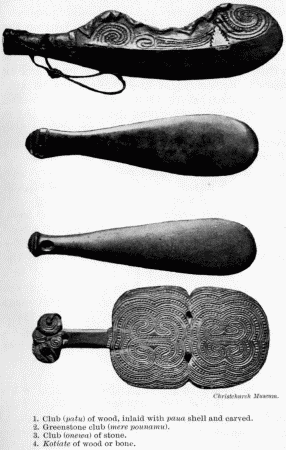

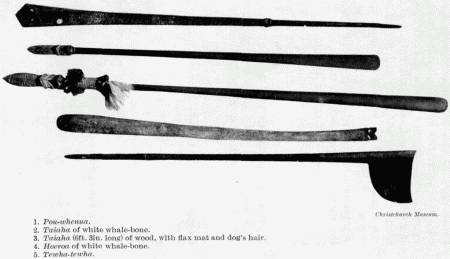

"There were at this time about three hundred of the natives on the deck, with Aimy, the chief, in the midst of them; every man was armed with a green stone, slung with a string around his waist. This weapon they call a 'mery,'[G] the stone being about a foot long, flat, and of an oblong shape, having both edges sharp, and a handle at the end. They use it for the purpose of killing their enemies, by striking them on the head.

"Smoke was now observed rising from several of the hills; and the natives appearing to be mustering on the beach from every part of the bay, the captain grew much afraid, and desired us to loosen the sails, and make haste down to get our dinners, as he intended to put to sea immediately. As soon as we had dined, we went aloft, and I proceeded to loosen the jib. At this time, none of the crew was on deck except the captain and the cook, the chief mate being employed in loading some pistols at the cabin table.

"The natives seized this opportunity of commencing an attack upon the ship. First, the chief threw off the mat which he wore as a cloak, and, brandishing a tomahawk in his hand, began a war-song, when all the rest immediately threw off their mats likewise, and, being entirely naked, began to dance with such violence that I thought they would have stove in the ship's deck.

"The captain, in the meantime, was leaning against the companion, when one of the natives went unperceived behind him, and struck him three or four blows on the head with a tomahawk, which instantly killed him. The cook, on seeing him attacked, ran to his assistance, but was immediately murdered in the same manner.

"I now sat down on the jib-boom, with tears in my eyes, and trembling with terror.

"Here I next saw the chief mate come running up the companion ladder, but before he reached the deck he was struck on the back of the neck in the same manner as the captain and the cook had been. He fell with the blow, but did not die immediately.

"A number of the natives now rushed in at the cabin door, while others jumped down through the skylight, and others were employed in cutting the lanyards of the rigging of the stays. At the same time, four of our crew jumped overboard off the foreyard, but were picked up by some canoes that were coming from the shore, and immediately bound hand and foot.

"The natives now mounted the rigging, and drove the rest of the crew down, all of whom were made prisoners. One of the chiefs beckoned to me to come to him, which I immediately did, and surrendered myself. We were then put all together into a large canoe, our hands being tied; and the New Zealanders, searching us, took from us our knives, pipes, tobacco-boxes, and various other articles. The two dead bodies, and the wounded mate, were thrown into the canoe along with us. The mate groaned terribly, and seemed in great agony, the tomahawk having cut two inches deep into the back of his neck; and all the while one of the natives, who sat in the canoe with us, kept licking the blood from the wound with his tongue. Meantime, a number of women who had been left in the ship had jumped overboard, and were swimming to the shore, after having cut her cable, so that she drifted, and ran aground on the bar near the mouth of the river. The natives had not sense to shake the reefs out of the sails, but had chopped them off along the yards with their tomahawks, leaving the reefed part behind.

"The pigs, which we had bought from them, were, many of them, killed on board, and carried ashore dead in the canoes, and others were thrown overboard alive, and attempted to swim to the land; but many of them were killed in the water by the natives, who got astride on their backs, and then struck them on the head with their merys. Many of the canoes came to the land loaded with plunder from the ship; and numbers of the natives quarrelled about the division of the spoil, and fought and slew each other. I observed, too, that they broke up our water-casks for the sake of the iron hoops.

"While all this was going on, we were detained in the canoe; but at last, when the sun was set, they conveyed us on shore to one of the villages, where they tied us by the hands to several small trees. The mate had expired before we got on shore, so that there now remained only twelve of us alive. The three dead bodies were then brought forward, and hung up by the heels to the branch of a tree, in order that the dogs might not get at them. A number of large fires were also kindled on the beach, for the purpose of giving light to the canoes, which were employed all night in going backward and forward between the shore and the ship, although it rained the greater part of the time.

"Gentle reader," Rutherford continues, "we will now consider the sad situation we were in; our ship lost, three of our companions already killed, and the rest of us tied each to a tree, starving with hunger, wet, and cold, and knowing that we were in the hands of cannibals.

"The next morning, I observed that the surf had driven the ship over the bar, and she was now in the mouth of the river, and aground near the end of the village. Everything being now out of her, about ten o'clock in the morning they set fire to her; after which they all mustered together on an unoccupied piece of ground near the village, where they remained standing for some time; but at last they all sat down except five, who were chiefs, for whom a large ring was left vacant in the middle. The five chiefs, of whom Aimy was one, then approached the place where we were, and after they had stood consulting for some time, Aimy released me and another, and, taking us into the middle of the ring, made signs for us to sit down, which we did. In a few minutes, the other four chiefs came also into the ring, bringing along with them four more of our men, who were made to sit down beside us.

"The chiefs now walked backward and forward in the ring with their merys in their hands, and continued talking together for some time, but we understood nothing of what they said. The rest of the natives were all the while very silent, and seemed to listen to them with great attention. At length, one of the chiefs spoke to one of the natives who was seated on the ground, and the latter immediately rose, and, taking his tomahawk in his hand, went and killed the other six men who were tied to the trees. They groaned several times as they were struggling in the agonies of death, and at every groan the natives burst out in great fits of laughter.

"We could not refrain from weeping for the sad fate of our comrades, not knowing, at the same time, whose turn it might be next. Many of the natives, on seeing our tears, laughed aloud, and brandished their merys at us.

"Some of them now proceeded to dig eight large round holes, each about a foot deep, into which they afterwards put a great quantity of dry wood, and covered it over with a number of stones. They then set fire to the wood, which continued burning till the stones became red hot. In the meantime, some of them were employed in stripping the bodies of my deceased shipmates, which they afterwards cut up, for the purpose of cooking them, having first washed them in the river, and then brought them and laid them down on several green boughs which had been broken off the trees and spread on the ground, near the fires, for that purpose.

"The stones being now red hot, the largest pieces of the burning wood were pulled from under them and thrown away, and some green bushes, having been first dipped in water, were laid round their edges, while they were at the same time covered over with a few green leaves. The mangled bodies were then laid upon the top of the leaves, with a quantity of leaves also strewed over them; and after this a straw mat was spread over the top of each hole. Lastly, about three pints of water were poured upon each mat, which, running through to the stones, caused a great steam, and then the whole was instantly covered with earth.

"They afterwards gave us some roasted fish to eat, and three women were employed in roasting fern-root for us. When they had roasted it, they laid it on a stone, and beat it with a piece of wood, until it became soft like dough. When cold again, however, it becomes hard, and snaps like gingerbread. We ate but sparingly of what they gave us. After this they took us to a house, and gave each of us a mat and some dried grass to sleep upon. Here we spent the night, two of the chiefs sleeping along with us.

"We got up next morning as soon as it was daylight, as did also the two chiefs, and went and sat down outside the house. Here we found a number of women busy in making baskets of green flax, into some of which, when they were finished, the bodies of our messmates, which had been cooking all night, were put, while others were filled with potatoes, which had been prepared by a similar process.

"I observed some of the children tearing the flesh from the bones of our comrades, before they were taken from the fires. A short time after this the chiefs assembled, and, having seated themselves on the ground, the baskets were placed before them and they proceeded to divide the flesh among the multitude, at the rate of a basket among so many. They also sent us a basket of potatoes and some of the flesh, which resembled pork; but instead of partaking of it we shuddered at the very idea of such an unnatural and horrid custom, and made a present of it to one of the natives."

According to this account, the editor says, the attack made upon the "Agnes" would seem to have been altogether unprovoked by the conduct either of the captain or any of the crew; but we must not, in matters of this kind, assume that we are in possession of the whole truth, when we have heard the statement of only one of the parties. What may have been the exact nature of the offence given to the natives in the present case, the narrative we have just transcribed hardly gives us any data even for conjecturing; unless we are to suppose that their vindictive feelings were called forth by the manner in which their pilfering may have been resented or punished, about which, however, nothing is said in the account. But perhaps, after all, it is not necessary to refer their hostility to any immediate cause of this kind. These savages had probably many old injuries, sustained from former European visitors, yet unrevenged; and, according to their notions, therefore, they had reason enough to hold every ship that approached their coast an enemy, and a fair subject for spoliation. It is lamentable that the conduct of Europeans should have offered them an excuse for such conduct.

The wanton cruelties committed upon these people by the commanders and crews of many of the vessels that have been of late years in the habit of resorting to their shores, are testified to, by too many evidences, to allow us to doubt the enormous extent to which they have been carried; and they are, at the same time, too much in the spirit of that systematic aggression and violence, which even British sailors are apt to conceive themselves entitled to practise upon naked and unarmed savages, to make the fact of their perpetration a matter of surprise to us. We must refer to Mr. Nicholas's book[H] for many specific instances of such atrocities; but we may merely mention here that the conduct in question is distinctly noticed and denounced in the strongest terms, both in a proclamation by Governor Macquarie, dated the 9th of November, 1814, and also in another by Sir Thomas Brisbane, dated the 17th of May, 1824. So strong a feeling, indeed, had been excited upon this subject among the more respectable inhabitants of the English colony, that, in the year 1814, a society was formed in Sydney Town, with the Governor at its head, for the especial protection of the natives of the South Sea Islands against the oppressions practised upon them by the crews of European vessels.

The reports of the missionaries likewise abound in notices of the flagrant barbarities by which, in New Zealand, as well as elsewhere, the white man has signalised his superiority over his darker-complexioned brother. But it may be enough to quote one of their statements, namely, that within the first two or three years after the establishment of the society's settlement at the Bay of Islands, not less than a hundred at least of the natives had been murdered by Europeans in their immediate neighbourhood. With such facts on record, it ought indeed to excite but little of our surprise, that the sight of the white man's ship in their horizon should be to these injured people in every district the signal for a general muster, to meet the universal foe, and, if it may be accomplished by force or cunning, to gratify the great passion of savage life—revenge.

The circumstances of this attack are all illustrative of the New Zealand character; and, indeed, the whole narrative is strikingly accordant with the accounts we have from other sources of the manner in which these savages are wont to act on such occasions, although there certainly never has before appeared so minute and complete a detail of any similar transaction. The gathering of the inland population by fires lighted on the hills, the previous crowding and almost complete occupation of the vessel, the sly and patient watching for the moment of opportunity, the instant seizure of it when it came, the management of the whole with such precision and skill, as in the case of the "Boyd,"[I] and indeed in every other known instance, while the success of the movement was perfect—this result was obtained without the expense of so much as a drop of blood on the part of the assailants—all these things are the uniform accompaniments of New Zealand treachery when displayed in such enterprises.

The rule of military tactics among this people is, in the first place, if possible, to surprise their enemies; and, in the second, to endeavour to alarm and confound them. This latter is doubtless partly the purpose of the song and dance, which form with them the constant prelude to the assault, although these vehement expressions of passion operate also powerfully as excitements to their own sanguinary valour and contempt of death.

Rutherford's description of the violence with which they danced on board the ship in the present case, immediately before commencing their attack on the crew, reminds us strikingly, even by its expression, of the account Crozet gives us, in his narrative of the voyage of M. Marion, of their exhibitions of a similar sort even when they were only in sport. "They would often dance," says he "with such fury when on board the ship that we feared they would drive in our deck."

The alleged cannibalism of the New Zealanders is a subject that has given rise to a good deal of controversy; and it has been even very recently contended that the imputation, if not altogether unfounded, is very nearly so, and that the horrid practice in question, if it does exist among these people at all, has certainly never been carried beyond the mere act of tasting human flesh, in obedience to some feeling of superstition or frantic revenge, and even that perpetrated only rarely and with repugnance.

Without attempting to theorise as to such a matter on the ground of such narrow views as ordinary experience would suggest, we may here state what the evidence is which we really have for the cannibalism of the New Zealanders.

Cook was the first who discovered the fact, which he did in his first visit to the country. The strongest proof of all was that which was obtained in Queen Charlotte Sound. Captain Cook having one day gone ashore here, accompanied by Mr. Banks, Dr. Solander, Tupia, and other persons belonging to the ship, found a family of the natives employed in dressing some provisions.

"The body of a dog," says Cook, "was at this time buried in their oven, and many provision baskets stood near it. Having cast our eyes carelessly into one of these as we passed it, we saw two bones pretty cleanly picked, which did not seem to be the bones of a dog, and which, upon a nearer examination, we discovered to be those of a human body. At this sight we were struck with horror, though it was only a confirmation of what we had heard many times since we arrived upon this coast. As we could have no doubt but the bones were human, neither could we have any doubt that the flesh which covered them had been eaten. They were found in a provision-basket; the flesh that remained appeared manifestly to have been dressed by fire, and in the gristles at the end were the marks of the teeth which had gnawed them.

"To put an end, however, to conjecture founded upon circumstances and appearances, we directed Tupia to ask what bones they were; and the Indians, without the least hesitation, answered, the bones of a man. They were then asked what was become of the flesh, and they replied that they had eaten it; 'but,' said Tupia, 'why did you not eat the body of the woman we saw floating upon the water?' 'The woman,' said they, 'died of disease; besides, she was our relation, and we eat only the bodies of our enemies, who are killed in battle.'

"Upon inquiry who the man was whose bones we had found, they told us that, about five days before, a boat belonging to their enemies came into the bay, with many persons on board, and that this man was one of seven whom they had killed.

"Though stronger evidence of this horrid practice prevailing among the inhabitants of this coast will scarcely be required, we have still stronger to give. One of us asked if they had any human bones with the flesh remaining upon them; and upon their answering us that all had been eaten, we affected to disbelieve that the bones were human, and said that they were the bones of a dog; upon which one of the Indians, with some eagerness, took hold of his own forearm, and thrusting it towards us, said that the bone which Mr. Banks held in his hand had belonged to that part of a human body; at the same time, to convince us that the flesh had been eaten, he took hold of his own arm with his teeth, and made a show of eating. He also bit and gnawed the bone which Mr. Banks had taken, drawing it through his mouth, and showing by signs that it had afforded a delicious repast. Some others of them, in a conversation with Tupia next day, confirmed all this in the fullest manner; and they were afterwards in the habit of bringing human bones, the flesh of which they had eaten, and offering them to the English for sale."

When Cook was at the same place in November, 1773, in the course of his second voyage, he obtained still stronger evidence of what he expressly calls their "great liking for this kind of food," his former account of their indulgence in which had been discredited, he tells us, by many. Some of the officers of the ship having gone one afternoon on shore, observed the head and bowels of a youth, who had been lately killed, lying on the beach; and one of them, having purchased the head, brought it on board. A piece of the flesh having then been broiled and given to one of the natives, he ate it immediately in the presence of all the officers and most of the men. Nothing is said of any aversion he seemed to feel to the shocking repast. Nay, when, upon Cook's return on board, for he had been at this time absent on shore, another piece of the flesh was broiled and brought to the quarter-deck, that he also might be an eye-witness of what his officers had already seen, one of the New Zealanders, he tells us, "ate it with surprising avidity. This," he adds, "had such an effect on some of our people as to make them sick."

Of the persons who sailed with Cook, no one seems eventually to have retained a doubt as to the prevalence of cannibalism among these savages. Mr. Burney, who had been long sceptical, was at last convinced of the fact, by what he observed when he went to look after the crew of the "Adventure's" boat who had been killed in Grass Cove; and both the elder and the younger Forster, who accompanied Cook on his second voyage, express their participation in the general belief. John Ledyard, who was afterwards distinguished as an adventurous African traveller, but who sailed with Cook in the capacity of a corporal of marines, bears testimony to the same fact.

It thus appears that the testimony of those who have actually visited New Zealand, in so far as it has been recorded, is unanimous upon this head.

To the authorities that have been already adduced, may be now added that of Rutherford, whose evidence, both in the extract from his journal that has been already given, and in other passages to which we shall afterwards have occasion to refer, is in perfect accordance with the statements of all preceding reporters entitled to speak upon the subject. The facts that have been quoted would seem to show that the eating of human flesh among this people is not merely an occasional excess, prompted only by the phrenzy of revenge, but that it is actually resorted to as a gratification of appetite, as well as of passion.

It is very probable, however, that the practice may have had its origin in those vindictive feelings which mix, to so remarkable a degree, in all the enmities and wars of these savages. This is a much more likely supposition than that it originated in the difficulty of procuring other food, in which case, as has been remarked, it could not well have, at any time, sprung up either in New Zealand or in almost any other of the countries in which it is known to prevail. Certain superstitious notions, besides, which are connected with it among this people, sufficiently indicate the motives which must have first led to it; for they believe that, by eating their enemies, they not only dishonour their bodies, but consign their souls to perpetual misery. This is stated by Cook.

Other accounts, which we have from more recent authorities, concur in showing that the person who eats any part of the body of another whom he has slain in battle, fancies he secures to himself thereby a portion of the valour or good fortune which had hitherto belonged to his dead enemy. The most common occasion, too, on which slaves are slain and eaten is by way of an offering to the "mana" of a chief or any of his family who may have been cut off in battle.

All this would go to prove that the cannibalism of the New Zealanders had, on its first introduction, been intimately associated with certain feelings or notions which seemed to demand the act as a duty, and not at all with any circumstances of distress or famine which compelled a resort to it as a dire necessity. There is too much reason for apprehending, however, that the unnatural repast, having ceased in this way to be regarded with that disgust with which it is turned from by every unpolluted appetite, has now become an enjoyment in which they not unfrequently indulge without any reference to the considerations which originally tempted them to partake of it. Indeed, such a result, instead of being incredible or improbable, would appear to be almost an inevitable consequence of the general and systematic perpetration, under any pretext, of so daring an outrage upon Nature as that of which these savages are, on all hands, allowed to be guilty.

The practice of cannibalism, which has prevailed among other nations as well as the New Zealanders, has probably not had always exactly the same origin. According to Mr. Mariner, it is of very recent introduction among the people of Tonga, having been unknown among them till it was imported about fifty or sixty years ago, along with other warlike tastes, by their neighbours of the Fiji Islands, whose assistance had been called in by one of the parties in a civil struggle. Here is an instance of the practice having originated purely in the ferocity engendered by the habit of war. In other cases it has, perhaps, arisen out of the kindred practice of offering up human beings as sacrifices to the gods.

Humboldt, in his work on the indigenous inhabitants of South America, gives us an interesting account of the introduction of this latter atrocity among the Aztecs, a people of Mexico, whose annals record its first perpetration to have taken place so late as the year 1317.

But the most extraordinary instance of cannibalism which is known to exist in the world is that practised by the Battas, an extensive and populous nation of Sumatra. These people, according to Sir Stamford Raffles, have a regular government, and deliberative assemblies; they possess a peculiar language and written character, can generally write, and have a talent for eloquence; they acknowledge a God, are fair and honourable in their dealings, and crimes amongst them are few; their country is highly cultivated. Yet this people, so far advanced in civilization, are cannibals upon principle and system. Mr. Marsden,[J] in his "History of Sumatra," seems to confine their cannibalism to the accustomed cases of prisoners taken in war and to other gratifications of revenge. But it is stated by Sir Stamford Raffles, upon testimony which is unimpeachable, that criminals and prisoners are not only eaten according to the law of the land, but that the same law permits their being mangled and eaten while alive. The following extraordinary account, which we extract from a letter of Sir Stamford Raffles to Mr. Marsden himself, dated February 27, 1820, is sufficiently revolting; but it is important as showing the wonderful influence of ancient customs in hardening the hearts of an otherwise mild and respectable people, and is therefore calculated to make us look with less severity upon the practices of the more ignorant New Zealanders. The progress of knowledge and of true religion can alone eradicate such fearful relics of a tremendous superstition—the offering, in another shape, to

Moloch, horrid king, besmear'd with bloodI have found all you say on the subject of cannibalism more than confirmed. I do not think you have even gone far enough. You might have broadly stated, that it is the practice, not only to eat the victim, but to eat him alive. I shall pass over the particulars of all previous information which I have received, and endeavour to give you, in a few words, the result of a deliberate inquiry from the Batta chiefs of Tappanooly. I caused the most intelligent to be assembled; and in the presence of Mr. Prince and Dr. Jack, obtained the following information, of the truth of which none of us have the least doubt. It is the universal and standing law of the Battas, that death by eating shall be inflicted in the following cases:—Adultery; midnight robbery; wars of importance, that is to say, one district against another, the prisoners are sacrificed; intermarrying in the same tribe, which is forbidden from the circumstance of their having ancestors in common; treacherous attacks on a house, village, or person. In all the above cases it is lawful for the victims to be eaten, and they are eaten alive, that is to say, they are not previously put to death. The victim is tied to a stake, with his arms extended, the party collect in a circle around him, and the chief gives the order to commence eating. The chief enemy, when it is a prisoner, or the chief party injured in other cases, has the first selection; and after he has cut off his slice, others cut off pieces according to their taste and fancy, until all the flesh is devoured. It is either eaten raw or grilled, and generally dipped in sambul (a preparation of Chili pepper and salt), which is always in readiness. Rajah Bandaharra, a Batta, and one of the chiefs of Tappanooly, asserted that he was present at a festival of this kind about eight years ago, at the village of Subluan, on the other side of the bay, not nine miles distant, where the heads may still be seen.

When the party is a prisoner taken in war, he is eaten immediately, and on the spot. Whether dead or alive he is equally eaten, and it is usual even to drag the bodies from the graves, and, after disinterring them, to eat the flesh. This only in cases of war. From the clear and concurring testimony of all parties, it is certain that it is the practice not to kill the victim till the whole of the flesh cut off by the party is eaten, should he live so long; the chief or party injured then comes forward and cuts off the head, which he carries home as a trophy. Within the last three years there have been two instances of this kind of punishment within ten miles of Tappanooly, and the heads are still preserved. In cases of adultery the injured party usually takes the ear or ears; but the ceremony is not allowed to take place except the wife's relations are present and partake of it. In these and other cases where the criminal is directed to be eaten, he is secured and kept for two or three days, till every person (that is to say males) is assembled. He is then eaten quietly, and in cold blood, with as much ceremony, and perhaps more, than attends the execution of a capital sentence in Europe.

The bones are scattered abroad after the flesh has been eaten, and the head alone preserved. The brains belong to the chief, or injured party, who usually preserves them in a bottle, for purposes of witchcraft, &c. They do not eat the bowels, but like the heart; and many drink the blood from bamboos. The palms of the hands and the soles of the feet are the delicacies of epicures. Horrid and diabolical as these practices may appear, it is no less true that they are the result of much deliberation among the parties, and seldom, except in the case of prisoners in war, the effect of immediate and private revenge. In all cases of crimes, the party has a regular trial, and no punishment can be inflicted until sentence is regularly and formally passed in the public fair. Here the chiefs of the neighbouring kampong assemble, hear the evidence, and deliberate upon the crime and probable guilt of the party; when condemned, the sentence is ratified by the chiefs drinking the tuah, or toddy, which is final, and may be considered equivalent to signing and sealing with us.

I was very particular in my inquiries whether the assembly were intoxicated on the occasions of these punishments. I was assured it was never the case. The people take rice with them, and eat it with the meat, but no tuah is allowed. The punishment is always inflicted in public. The men alone are allowed to partake, as the flesh of man is prohibited to women (probably from an apprehension they might become too fond of it). The flesh is not allowed to be carried away from the spot, but must be consumed at the time. I am assured that the Battas are more attached to these laws than the Mahomedans are to the Koran, and that the number of the punishments is very considerable. My informants considered that there could be no less than fifty or sixty men eaten in a year, and this in times of peace; but they were unable to estimate the true extent, considering the great population of the country; they were confident, however, that these laws were strictly enforced wherever the name of Batta was known, and that it was only in the immediate vicinity of our settlements that they were modified and neglected. For proof, they referred me to every Batta in the vicinity, and to the number of skulls to be seen in every village, each of which was from a victim of the kind.

With regard to the relish with which the parties devour the flesh, it appeared that, independent of the desire of revenge which may be supposed to exist among the principals, about one-half of the people eat it with a relish, and speak of it with delight; the other half, though present, may not partake. Human flesh is, however, generally considered preferable to cow or buffalo beef, or hog, and was admitted to be so even by my informants. Adverting to the possible origin of this practice, it was observed that formerly they ate their parents when too old for work; this, however, is no longer the case, and thus a step has been gained in civilization. It is admitted that the parties may be redeemed for a pecuniary compensation, but this is entirely at the option of the chief enemy or injured party, who, after his sentence is passed, may either have his victim eaten, or he may sell him for a slave; but the law is that he shall be eaten, and the prisoner is entirely at the mercy of his prosecutor.

The laws by which these sentences are inflicted are too well known to require reference to books, but I am promised some MS. accounts which relate to the subject. These laws are called huhum pinang àn,—from depang àn, to eat—law or sentence to eat.

I could give you many more details, but the above may be sufficient to show that our friends the Battas are even worse than you have represented them, and that those who are still sceptical have yet more to learn. I have also a great deal to say on the other side of the character, for the Battas have many virtues. I prize them highly.

FOOTNOTES:

[D]At the extreme north of the Philippine Islands.

Hawaii.

Phormium tenax.

méré.

Nicholas's "Voyage to New Zealand."

The transport "Boyd" was taken by Maoris and burned at Whangaroa Harbour in 1809. Most of the people on board were massacred, there being only four survivors out of seventy souls.

William Marsden, who was sent out from Dublin to Sumatra, about 1775, as a writer in the East India Company's service.

Rutherford and his comrades spent another night in the same manner as they had done the previous one; and on the following morning set out, in company with the five chiefs, on a journey into the interior.

When they left the coast, the ship was still burning. They were attended by about fifty natives, who were loaded with the plunder of the unfortunate vessel. That day, he calculates, they travelled only about ten miles, the journey being very fatiguing from the want of any regular roads, and the necessity for making their way through a succession of woods and swamps.

The village at which their walk terminated was the residence of one of the chiefs, whose name was Rangadi,[K] and who was received on his arrival by about two hundred of the inhabitants.

They came in a crowd, and, kneeling down around him, began to cry aloud and cut their arms, faces, and other parts of their bodies with pieces of sharp flint, of which each of them carried a number tied with a string about his neck, till the blood flowed copiously from their wounds.

These demonstrations of excited feeling, which Rutherford describes as merely their usual manner of receiving any of their friends who have been for some time absent, are rather more extravagant than seem to have been commonly observed to take place on such occasions in other parts of the island. Mr. Marsden,[L] however, states that on Korro-korro's[M] return from Port Jackson, many of the women of his tribe who came out to receive him "cut themselves in their faces, arms, and breasts with sharp shells or flints, till the blood streamed down." Some time after, when Duaterra[N] and Shungie[O] went on shore at the Bay of Islands, they met with a similar reception from the females of their tribes. Mr. Savage asserts that this cutting of their faces by the women always takes place on the meeting of friends who have been long separated; but that the ceremony consists only of embracing and crying, when the separation of the parties has been short. It may be remarked that the custom of receiving strangers with tears, by way of doing them honour, has prevailed with other savages. Among the native tribes of Brazil, according to Lafitau, it used to be the custom for the women, on the approach of any one to whom they wished to show especial fidelity, to crouch down on their heels, and, spreading their hands over their faces, to remain for a considerable time in that posture, howling in a sort of cadence, and shedding tears. Among the Sioux, again, it was the duty of the men to perform this ceremony of lamentation on such occasions, which they did standing, and laying their hands on the heads of their visitors.

In some cases, the wounds which the New Zealand women inflict on themselves are intended to express their grief for friends who have perished in war; and probably this may have been a reason for the strong exhibition of feeling in the instance just noticed by Rutherford, as the chiefs had then returned from an expedition. Such a mode of mourning has been often observed in New Zealand. During the time that Cruise was at the Bay of Islands, they found one day, upon going on shore, that a body of the natives had just returned from a war expedition, in which they had taken considerable numbers of prisoners, consisting of men, women, and children, some of the latter of whom were not two years old; and among the women was one, distinguished by her superior beauty, who sat apart from the rest upon the beach, and, though silent, seemed buried in affliction. They learned that her father, a chief of some consequence, had been killed by the man whose prisoner she now was, and who kept near her during the greater part of the day.

The officers remained on shore till the evening; "and as we were preparing to return to the ship," continues Cruise, "we were drawn to that part of the beach where the prisoners were, by the most doleful cries and lamentations. Here was the interesting young slave in a situation that ought to have softened the heart of the most unfeeling. The man who had slain her father, having cut off his head, and preserved it by a process peculiar to these islanders, took it out of a basket, where it had hitherto been concealed, and threw it into the lap of the unhappy daughter." At once she seized it with a degree of phrenzy not to be described; and subsequently, with a bit of sharp shell, disfigured her person in so shocking a manner that in a few minutes not a vestige of her former beauty remained. They afterwards learned that this fellow had married the very woman he had treated with such singular barbarity.

The crying, however, seems to be a ceremony that takes place universally on the meeting of friends who have been for some time parted. We may give, in illustration of this custom, Cruise's description of the reception by their relatives of the nine New Zealanders who came along with him in the "Dromedary" from Port Jackson.

"When their fathers, brothers, etc., were admitted into the ship," says he, "the scene exceeded description; the muskets were all laid aside, and every appearance of joy vanished. It is customary with these extraordinary people to go through the same ceremony upon meeting as upon taking leave of their friends. They join their noses together, and remain in this position for at least half-an-hour;[P] during which time they sob and howl in the most doleful manner. If there be many friends gathered around the person who has returned, the nearest relation takes possession of his nose, while the others hang upon his arms, shoulders, and legs, and keep perfect time with the chief mourner (if he may be so called) in the various expressions of his lamentation. This ended, they resume their wonted cheerfulness, and enter into a detail of all that has happened during their separation. As there were nine New Zealanders just returned, and more than three times that number to commemorate the event, the howl was quite tremendous, and so novel to almost every one in the ship that it was with difficulty our people's attention could be kept to matters at that moment more essential. Little Repero, who had frequently boasted, during the passage, that he was too much of an Englishman ever to cry again, made a strong effort when his father, Shungie, approached him, to keep his word; but his early habit soon got the better of his resolution, and he evinced, if possible, more distress than any of the others."

The sudden thawing of poor Repero's heroic resolves was an incident exactly similar to another which Mr. Nicholas had witnessed. Among the New Zealanders who, after having resided for some time in New South Wales, returned with him and Mr. Marsden to their native country, was one named Tooi,[Q] who prided himself greatly on being able to imitate European manners; and accordingly, declaring that he would not cry, but would behave like an Englishman, began, as the trying moment approached, to converse most manfully with Mr. Nicholas, evidently, however, forcing his spirits the whole time. But "his fortitude," continues Nicholas, "was very soon subdued; for being joined by a young chief about his own age, and one of his best friends, he flew to his arms, and, bursting into tears, indulged exactly the same emotions as the others."

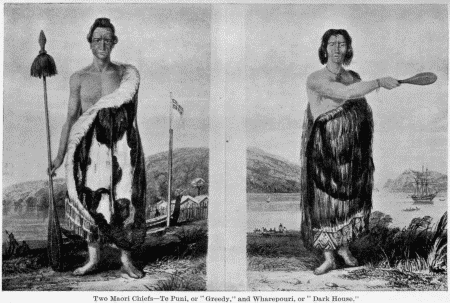

Tooi was afterwards brought to England, and remained for some time in this country. He was in attendance upon his brother Korro-korro, one of the greatest chiefs in the neighbourhood of the Bay of Islands, and, as well as Shungie, who has just been mentioned, celebrated all over the country for his love of fighting, and the number of victories he had won.

Yet even this hardy warrior was no more proof than any one of his wives or children against this strange habit of emotion. The first person he met on his landing happened to be his aunt, whose appearance, as, bent to the earth with age and infirmities, she ascended a hill, supporting herself upon a long staff, Nicholas compares to that which we might conceive the Sibyl bore, when she presented herself to Tarquin. Yet, when she came up to Korro-korro, the chief, we are told, having fallen upon her neck, and applied his nose to hers, the two continued in this posture for some minutes, talking together in a low and mournful voice; and then disengaging themselves, they gave vent to their feelings by weeping bitterly, the chief remaining for about a quarter of an hour leaning on his musket, while the big drops continued to roll down his cheeks.

The old woman's daughter, who had come along with her, then made her approach, and another scene, if possible of still more tumultuous tenderness than the former, took place between the two cousins. The chief hung, as before, in an agony of affection, on the neck of his relation; and "as for the woman," says Nicholas, "she was so affected that the mat she wore was literally soaked through with her tears." A passionate attachment to friends is, indeed, one of the most prevailing feelings of the savage state. Dampier tells us of an Indian who recovered his friend unexpectedly on the island of Juan Fernandez, and who immediately prostrated himself on the ground at his feet. "We stood gazing in silence," says the manly sailor, "at this tender scene."

The house of the chief to which Rutherford and his comrades were taken was the largest in the village, being both long and wide, although very low, and having no other entrance than an aperture, which was shut by means of a sliding door, and was so much lower even than the roof that it was necessary to crawl upon the hands and knees to get through it.

Two large pigs and a quantity of potatoes were now cooked; and when they were ready, a portion having been allotted to the slaves, who are never permitted to eat along with the chiefs, the latter sat down to their repast, the white men taking their places beside them.

The feast was not held within the house, but in the open air; and the meat that was not consumed was hung up on posts for a future occasion. One of the strongest prejudices of the New Zealanders is an aversion to be where any article of food is suspended over their heads; and on this account, they never permit anything eatable to be brought within their huts, but take all their meals out of doors, in an open space adjoining to the house, which has been called by some writers the kitchen, it being there that the meal is cooked as well as eaten. Crozet says that every one of these kitchens has in it a cooking hole, dug in the ground, of about two feet in diameter, and between one and two feet deep. Even when the natives are confined to their beds by sickness, and, it may be, at the point of death, they must receive whatever food they take in this outer room, which, however, is sometimes provided with a shed, supported upon posts, although in no case does it appear to be enclosed by walls. It is here, accordingly, that those who are in so weak a state from illness as not to be able to bear removal from one place to another usually have their couches spread; as, were they to choose to recline inside the house, it would be necessary to leave them to die of want.

Nicholas, in the course of an excursion which he made in the neighbourhood of the Bay of Islands, was once not a little annoyed and put out of humour by this absurd superstition. It rained heavily when he and Marsden arrived very hungry at a village belonging to a chief of their acquaintance, where, although the chief was not at home, they were very hospitably received, their friends proceeding immediately to dress some potatoes to make them a dinner. But after they had prepared the meal, they insisted, as usual, that it should be eaten in the open air.

This condition, Nicholas, in the circumstances, naturally thought a somewhat hard one; but it was absolutely necessary either to comply with it, or to go without potatoes. To make matters worse, the dining-room had not even a shed. So they had no course left but to take shelter in the best way they could, under a projection from the roof of the house, extending about three feet; and here they contrived to take their repast, without being very much drenched. However, they were not allowed this indulgence without many anxious scruples on the part of their friends, who considered even their venturing so near to the house on such an occasion as an act of daring impiety. As they had got possession of the potatoes, their entertainers, though very much shocked and alarmed, did not proceed to such rudeness as to take these from them again; but whenever they wanted to drink out of the calabash that had been brought to them, they obliged them to thrust out their heads for it from under the covering, although the rain continued to fall in torrents.

Fatigued as he was, and vexed at being in this way kept out of the comfortable shelter he had expected, Nicholas at last commenced inveighing, he tells us, against the inhospitable custom, with much acrimony; and as Tooi, who was with them, had always shown so strong a predilection for European customs, he turned to him, and asked him if he did not think that these notions of his countrymen were all gammon. Tooi, however, replied sharply, that "it was no gammon at all"; adding, "New Zealand man say that Mr. Marsden's crackee crackee (preaching) of a Sunday is all gammon," in indignant retaliation for the insult that had been offered to his national customs.

But the worst part of the adventure was yet to come; for as the night was now fast approaching, and the rain still pouring down incessantly, it was impossible to think of returning to the ship; "and we were therefore," continues Nicholas, "obliged to resolve upon remaining where we were, although we had no bed to expect, nor even a comfortable floor to stretch upon. We wrapped ourselves up in our great coats, which by good fortune we had brought with us, and when the hour of rest came on, laid ourselves down under the projecting roof, choosing rather to remain here together, than to go into the house and mingle with its crowded inmates, which we knew would be very disagreeable. Mr. Marsden, who is blessed by nature with a strong constitution, and capable of enduring almost any fatigue, was very soon asleep; but I, who have not been cast in a Herculean mould, nor much accustomed to severe privations, felt all the misery of the situation, while the cold and wet to which I was unavoidably exposed, from the place being open, brought on a violent rheumatic headache, that prevented me from once closing my eyes, and kept me awake in the greatest anguish.

"Being at length driven from this wretched shelter by the rain, which was still beating against me, I crept into the house, through the narrow aperture that served for a door; and, stretching myself among my rude friends, I endeavoured to get some repose; but I found this equally impossible here as in the place I had left. The pain in my head still continued; and those around me, being all buried in profound sleep, played, during the whole night, such music through their noses, as effectually prevented me from being able to join in the same chorus."

On one occasion, in the course of his second visit, Marsden spent the night in the house of a chief, the entrance to which was of such narrow dimensions that he could not, he says, creep in without taking his coat off. The apartment altogether measured only about fourteen feet by ten; and when he looked into it he found a fire blazing on the centre of the floor, which made the place as hot as an oven, there being no vent for the smoke, except through the hole which served for a door. However, the fire, on his entreating it, was taken out, and then he and his friend, Butler, who was with him, crept in, and were followed by their entertainer, his wife and nephew. The hut was still extremely hot, and they perspired profusely when they lay down, but they were a little relieved by the New Zealanders consenting to allow the door to remain open during the night.

Another time he was thrust into a still closer dormitory. "The entrance," says he, "was just sufficient for a man to creep into. Being very cold, I was glad to occupy such a warm berth. I judged the hut to be about eight feet wide, and twelve long. It had a fire in the centre; and no vent either for smoke or heat. The chiefs who were with us threw off their mats and lay down close together in a state of perfect nudity. I had not been many minutes in this oven, before I found the heat and smoke, above, below, and on every side, to be insufferable. Though the night was cold, Mr. Kendall and myself were compelled to quit our habitation. I crept out, and walked in the village, to see if I could meet with a shed to keep me from the damp air till the morning. I found one empty, into which I entered. I had not been long under my present cover before I observed a chief, who came with us from the last village, come out of the hut which I had left, perfectly naked. The moon shone very bright. I saw him run from hut to hut, till at last he found me under my shed, and urged me to return. I told him I could not bear the heat, and requested him to allow me to remain where I was; to which he at length consented with reluctance. I was surprised at the little effect that heat or cold seemed to have upon him. He had come out of the hut smoking like a hot loaf drawn from the oven, walked about to find me, and then sat down, conversed some time, without any clothing, though the night was cold. Mr. Kendall remained sitting under his mat, in the open air, till morning."

The New Zealanders make only two meals in the day, one in the morning and another at sunset; but their voracity when they do eat is often very great. Nicholas remarks that the chiefs and their followers, with whom he made the voyage from Port Jackson, used, while in the ship, to seize upon every thing they could lay their hands upon in the shape of food. In consequence of this habit of consuming an extraordinary quantity of food, a New Zealander, with all his powers of endurance in other respects, suffers dreadfully when he has not the usual means of satisfying his hunger.

The huts of the common people are described as very wretched, and little better than sheds; but Nicholas mentions that those which he saw in the northern part of the country had uniformly well-cultivated gardens attached to them, which were stocked with turnips, and sweet and common potatoes. Crozet tells us that the only articles of furniture the French ever found in these huts, were fishing-hooks, nets, and lines, calabashes containing water, a few tools made of stone, and several cloaks and other garments suspended from the walls.

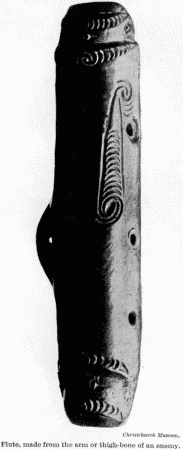

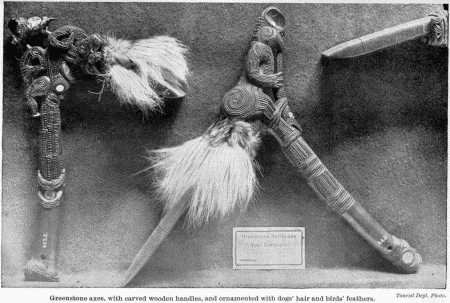

Amongst the tools, one resembling our adze is in the most common use; and it is remarkable that the handles of these implements are often composed of human bones. In the museum of the Church Missionary Society there are adzes, the handle of one of which is formed of the bone of a human arm, and another of that of a leg.

The common people generally sleep in the open air, in a sitting posture, and covered by their mats, all but the head; which has been described as giving them the appearance of so many hay-cocks or beehives.

The house of the chief is generally, as Rutherford found it to be in the present case, the largest in the village; but every village has, in addition to the dwelling-houses of which it consists, a public storehouse, or repository of the common stock of sweet potatoes, which is a still larger structure than the habitation of the chief. One which Cruise describes was erected upon several posts driven into the ground, which were floored over with deals at the height of about four feet, as a foundation. Both the sides and the roof were compactly formed of stakes intertwisted with grass; and a sliding doorway, scarcely large enough to admit a man, formed the entrance. The roof projected over this, and was ornamented with pieces of plank painted red, and having a variety of grotesque figures carved on them. The whole building was about twenty feet long, eight feet wide, and five feet high.

The residences of the chiefs are built upon the ground, and have generally the floor, and a small space in front, neatly paved; but they are so low that a man can stand upright in very few of them. The huts, as well as the storehouses, are adorned with carving over the door.

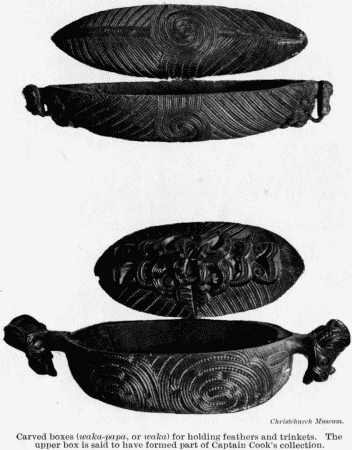

One of the arts in which the New Zealanders most excel is that of carving in wood. Some of their performances in this way are, no doubt, grotesque enough; but they often display both a taste and ingenuity which, especially when we consider their miserably imperfect tools, it is impossible to behold without admiration. This is one of the arts which, even in civilized countries, does not seem to flourish best in a highly advanced state of society. Even among ourselves, it certainly is not at present cultivated with so much success as it was a century or two ago.

Machinery, the monopolizing power of our age, is not well fitted to the production of striking effects in this particular branch of the arts. Fine carving is displayed, as in the works of Gibbons, by a rich and natural variety, altogether opposed to that faultless and inflexible regularity of operation which is the perfection of a machine. Hence the lathe, with all the miraculous capabilities it has been made to evolve, can never here come into successful competition with the chisel, in so far as the quality and spirit of the performance are concerned; but the former may, nevertheless, drive the latter out of the market, and seems in a great measure to have done so, by the infinitely superior facility and rapidity of its operation. Hence the gradual decay, and almost extinction among us, of this old art, of which former ages have left us so many beautiful specimens. It is said to survive now, if at all, not among our artists by profession, whose taste is expended upon higher objects, but among the common workmen of our villages, who have pursued it as an amusement, long after it has ceased to be profitable.