The Project Gutenberg EBook of Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States From Interviews with Former Slaves: Volume II, Arkansas Narratives, Part 2, by Work Projects Administration This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States From Interviews with Former Slaves: Volume II, Arkansas Narratives, Part 2 Author: Work Projects Administration Release Date: October 11, 2004 [EBook #13700] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SLAVE NARRATIVES *** Produced by Jeannie Howse, Andrea Ball, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team from images provided by the Library of Congress, Manuscript Division.

[TR: ***] = Transcriber Note

[HW: ***] = Handwritten Note

Illustrated with Photographs

WASHINGTON 1941

[TR: Some interviews were date-stamped; these dates have been added to interview headers in brackets. Where part of date could not be determined -- has been substituted. These dates do not appear to represent actual interview dates, rather dates completed interviews were received or perhaps transcription dates.]

"I was born three miles west of Starkville, Mississippi on a pretty tolerable large farm. My folks was bought from a speculator drove come by. They come from Sanders in South Ca'lina. Master Charlie Cannon bought a whole drove of us, both my grandparents on both sides. He had five farms, big size farms. Saturday was ration day.

"Our master built us a church in our quarters and sont his preacher to preach to us. He was a white preacher. Said he wanted his slaves to be Christians.

"I never went to school in my life. I was taught by the fireside to be obedient and not steal.

"We et outer trays hewed out of logs. Three of us would eat together. We had wooden spoons the boys made whittling about in cold rainy weather. We all had gourds to drink outer. When we had milk we'd get on our knees and turn up the tray, same way wid pot-liquor. They give the grown up the meat and us pot-liquor.

"Pa was a blacksmith. He got a little work from other plantations. The third year of the surrender he bought us a cow. The master was dead. He never went to war. He went in the black jack thickets. His sons wasn't old enough to go to war. Pa seemed to like ole master. The overseer was white looking like the master but I don't know if he was white man or nigger. Ole master wouldn't let him whoop much as he pleased. Master held him off on whooping.

"When the master come to the quarters us children line up and sit and look at him. When he'd go on off we'd hike out and play. He didn't care if we look at him.

"My pa was light about my color. Ma was dark. I heard them say she was part Creek (Indian).

"Folks was modester before the children than they are now. The children was sent to play or git a bucket cool water from the spring. Everything we said wasn't smart like what children say now. We was seen and not heard. Not seen too much or somebody be stepping 'side to pick up a brush to nettle our legs. Then we'd run and holler both.

"Now and then a book come about and it was hid. Better not be caught looking at books.

"Times wasn't bad 'ceptin' them speculator droves and way they got worked too hard and frailed. Some folks was treated very good, some killed.

"Folks getting mean now. They living in hopes and lazing about. They work some."

"I member when they freed the people.

"I was born in Bedie Kellog's yard and I know she said, 'Zenie, I hate to give you up, I'd like to keep you.' But my mother said, 'No, ma'am, I can't give Zenie up.'

"We still stayed there on the place and I was settled and growed up when I left there.

"I'm old. I feels my age too. I may not look old but I feels it.

"Yes ma'am, I member when they carried us to church under bresh arbors. Old folks had rags on their hair. Yes'm, I been here.

"My father was a Missionary Baptist preacher and he was a preacher. Didn't know 'A' from 'B' but he was a preacher. Everbody knowed Jake Alsbrooks. He preached all over that country of North Carolina. They'd be as many white folks as colored. They'd give him money and he never called for a collection in his life. Why one Sunday they give him sixty-five dollars to help buy a horse.

"Fore I left the old county, I member the boss man, Henry Grady, come by and tell my mother, 'I'm gwine to town now, have my dinner ready when I come back—kill a chicken.' She was one of the cooks. Used to have us chillun pick dewberries and blackberries and bring em to the house.

"Yes, I done left there thirty-six years—will be this August.

"When we was small, my daddy would make horse collars, cotton baskets and mattresses at night and work in the field in the daytime and preach on Sunday. He fell down in Bedie Kellog's lot throwin' up shucks in the barn. He was standin' on the wagon and I guess he lost his balance. They sent and got the best doctor in the country and he said he broke his nabel string. They preached his funeral ever year for five years. Seemed like they just couldn't give him up.

"White folks told my mother if she wouldn't marry again and mess up Uncle Jake's chillun, they'd help her, but she married that man and he beat us so I don't know how I can remember anything. He wouldn't let us go to school. Had to work and just live like pigs.

"Oh, I used to be a tiger bout work, but I fell on the ice in 'twenty-nine and I ain't never got over it. I said I just had a death shock.

"I never went to school but three months in my life. Didn't go long enough to learn anything.

"I was bout a mile from where I was born when I professed religion. My daddy had taught us the right way. I tell you, in them days you couldn't join the church unless you had been changed.

"I come here when they was emigratin' the folks here to Arkansas."

[TR: Some word pronunciation was marked in this interview. Letters surrounded by [] represent long vowels.]

"I was born in Tennessee close to Memphis. I remember seein' the Yankees. I was most too little to be very scared of them. They had their guns but they didn't bother us. I was born a slave. My mother cooked for Jane and Silas Wory. My mother's name was Caroline. My father's name was John. An old bachelor named Jim Bledsoe owned him. When the war was over I don't remember what happened. My mother moved away. She and my father didn't live together. I had one brother, Proctor. I expect he is dead. He lived in California last I heard of him.

"They just expected freedom all I ever heard. I know they didn't expect the white folks to give them no land cause the man what owned the land bought it hisself foe he bought the hands whut he put on it. They thought they was ruined bad enouf when the hands left them. They kept the land and that is about all there was left. Whut the Yankees didn't take they wasted and set fire to it. They set fire to the rail fences so the stock would get out all they didn't kill and take off. Both sides was mean. But it seemed like cause they was fightin' down here on the Souths ground it was the wurst here. Now that's just the way I sees it. They done one more thing too. They put any colored man in the front where he would get killed first and they stayed sorter behind in the back lines. When they come along they try to get the colored men to go with them and that's the way they got treated. I didn't know where anybody was made to stay on after the war. They was lucky if they had a place to stay at. There wasn't anything to do with if they stayed. Times was awful unsettled for a long time. People whut went to the cities died. I don't know they caught diseases and changing the ways of eatin' and livin' I guess whut done it. They died mighty fast for awhile. I knowed some of them and I heard 'em talking.

"That period after the war was a hard time. It sho was harder than the depression. It lasted a long time. Folks got a lots now besides what they put up with then. Seemed like they thought if they be free they never have no work to do and jess have plenty to eat and wear. They found it different and when it was cold they had no wood like they been used to. I don't believe in the colored race being slaves cause of the color but the war didn't make times much better for a long time. Some of them had a worse time. So many soon got sick and died. They died of Consumption and fevers and nearly froze. Some near 'bout starved. The colored folks just scattered 'bout huntin' work after the war.

"I heard of the Ku Klux but I never seen one.

"I never voted. I don't believe in it.

"I never heard of any uprisings. I don't know nobody in that rebellion (Nat Turner).

"I used to sing to my children and in the field.

"I lived on the farm till I come to my daughters to live. I like it better then in town. We homesteaded a place at Grunfield (Zint) and my sister bought it. We barely made a living and never had money to lay up.

"I don't know what they'll (young generation) do. Things going so fast. I'm glad I lived when I did. I think it's been the best time for p[o]r folks. Some now got too much and some not got nothin'. That what I believe make times seem so hard."

"I was born up here on the Biscoe place before Mr. Biscoe was heard of in this country. I'm for the world like my daddy. He was light as I is. I'm jus' his size and make. There was three of us boys. Dan was the oldest; he was my own brother, and Ed was my half-brother. My daddy was a fellar of few words and long betwix' 'em. He was in the Old War (Civil War). He was shot in his right ankle and never would let it be took out. Mother had been a cook. She and my grandmother was sold in South Carolina and brought out here. Mother's name was Sallie Harry. Judging by them being Harrys that might been who owned them before they was sold. She was about as light as me. Mother died when I was a litter bit er of a fellar. Then me and Dan lived from house to house. Grandma Harry and my Aunt Mat and Jesse Dove raised us. My daddy married right er way ag'in.

"I recollect mighty little about the war. We lived back in the woods and swamps. I was afraid of the soldiers. I seen them pass by. I was so little I can barely recollect seeing them and hiding from them.

"When we lived over about Forrest City I seen the Ku Klux whoop Joe Saw and Bill Reed. It was at night. They was tied to trees and whooped with a leather snake whoop. I couldn't say how it come up but they sure poured it on them. There was a crowd come up during the acting. I was scared to death then. After then I had mighty little use for dressed-up folks what go around at night (Ku Klux). I can tell you no sich thing ever took place as I heard of at Biscoe. We had our own two officers and white officers and we get along all the time tollerably well together."

[TR: Some word pronunciation was marked in this interview. Letters surrounded by [] represent long vowels.]

"I answer all your questions I knows lady.

"When de Civil War goin on I heard lots folks talking. I don't know what all they did say. It was a war mong de white folks. Niggers had no say in it. Heap ob them went to wait on their masters what went to fight. Niggers didn't know what the fight war bout. Yankey troops come take everything we had made, take it to the Bluff (DeValls Bluff), waste it and eat it. He claim to be friend to the black man an do him jes dater way. De niggers what had any sense tall stuck to the white folks. Niggers what I knowed didn't spec nothin an they sho didn't get nothin but freedom.

"I was sold. Yes mam I sho was. Jes put up on a platform and auctioned off. Sold right here in Des Arc. Nom taint right. My old mistress [Mrs. Snibley] whoop me till I run off and they took me back when they found out where I lef from. I stayed way bout two weeks.

"One man I sho was glad didn't get me cause he whoop me. N[o]'[o]m he didn't get me. I heard him puttin up the prices and I sho hope he didn't get me.

"I don't know whar I come from. Old Missus Snibley kept my hat pulled down over my face so I couldn't see de way to go back. I didn't want to come and I say I go right back. Whar I set, right between old missus and master on de front seat ob de wagon and my ma set between missus Snibley's two girls right behind us. I recken it was a covered wagon. The girls name was Florence and Emma. Old master Snibley never whip me but old Missus sho did pile it on me. Noom I didn't lack her. I run away. He died f[o] the war was over. I did leave her when de war was over.

"I saw a heap ob bushwhackers and carpet bagger but I nebber seed no Ku Klux. I heard battles of the bushwhackers out at the Wattensaw bridge [Iron bridge]. I was scared might near all de time for four years. Noom I didn't want no soldiers to get me.

"I recken I wo long britches when de war started cause when I pulled off dresses I woe long britches. Never wo no short ones. Nigger boys and white boys too wore loose dresses till they was four, five or six years old in them times. They put on britches when they big nough to help at the field.

"I worked at the house and de field. I'se farmed all my life.

"I vote [HW: many] a time. I don't know what I vote. Noom I don't! I recken I votes Democrat, I don't know. It don't do no good. Noom I ain't voted in a long time. I don't know nothin bout votin. I never did.

"Noom I never owned no land, noom no home neither. I didn't need no home. The man I worked for give me a house on his place. I work for another man and he give me a house on his land. I owned a horse one time. I rode her.

"I don't know nuthin bout the young generation. I takes care bout myself. Dats all I'm able to do now. Some ob dem work. Nom they don't work hard as I did. I works now hard as they do. They ought to work. I don't know what going to become ob them. I can't help what they do.

"The times is hard fo old folks cause they ain't able to work and heap ob time they ain't no work fo em to do.

"Noom I lived at Bells, Arkansas for I come to Hickory Plains and Des Arc. I don't know no kin but my mother. She died durin the war. Noom not all de white folks good to the niggers. Some mean. They whoop em. Some white folks good. Jes lak de niggers, deres some ob em mighty good and some ob em mean.

"I works when I can get a little to do and de relief gives me a little.

"I am er hundred years old! Cause I knows I is. White folks all tell you I am."

"I was born in West Point, Mississippi. My folks' owners was Master Harris and Liddie Harris. My parent's name was Sely Sikes. She was mother of seven children. Papa was name Owen Sikes. He never was whooped. They had different owners. Both my grandparents was dead on both sides. I never seen them.

"Mama said her owners wasn't good. Her riding boss put a scar on her back she took to her grave. It was deep and a foot long. He wanted to whoop her naked. He had the colored men hold her and he whooped her. She run off and when her owner come home she come to him at his house and told him all about it. She had been in the woods about a week she reckon. She had a baby she had left. The old mistress done had it brought to her. She was nursing it. She had a sicking baby of her own. She kept that baby. Mama said her breast was way out and the doctor had to come wait on her; it nearly ruined.

"Mama said her master was so mad he cursed the overseer, paid him, and give him ten minutes to leave his place. He left in a hurry. That was her very first baby. She was raising a family, so they put her a nurse at the house. She had been ploughing. She had big fine children. They was proud of them. She raised a big family. She took care of all her and Miss Liddie's babies and washed their hippins. Never no soap went on them she said reason she had that to do. Another woman cooked and another woman washed.

"Mama said she was sold once, away from her mother but they let her have her four children. She grieved for her old mama, 'fraid she would have a hard time. She sold for one thousand dollars. She said that was half price but freedom was coming on. She never laid eyes on her mama ag'in.

"After freedom they had gone to another place and the man owned the place run the Ku Klux off. They come there and he told them to go on away, if he need them he would call them back out there. They never came back, she said. They was scared to death of the Ku Klux. At the place where they was freed all the farm bells rung slow for freedom. That was for miles about. Their master told them up at his house. He said it was sad thing, no time for happiness, they hadn't 'sperienced it. But for them to come back he would divide long as what he had lasted. They didn't go off right at first. They was several years getting broke up. Some went, some stayed, some actually moved back. Like bees trying to find a setting place. Seem like they couldn't get to be satisfied even being free.

"I had eleven children my own self. I let the plough fly back and hit me once and now I got a tumor there. I love to plough. I got two children living. She comes to see me. She lives across over here. I don't hear from my boy. I reckon he living. I gets help from the relief on account I can't work much with this tumor."

[TR: Also reported as Maria Sutton Clements]

I don't know jes how old I is. Yes mum I show do member the war jes lack as if it was yesterday. I was born in Lincoln County, Georgia. My old mistress was named Frances Sutton. She was a real old lady. Her husband was dead. She had two sons Abraham and George. One of them tried to get old missus to sell my ma jes before the war broke out. He wanter sell her cause she too old to bear children. Sell her and buy young woman raise mo children to sell. Put em in the nigger drove and speculate on em. Young nigger, not stunted, strong made, they look at their wristes and ankles and chestes, bout grown bring the owner fifteen hundred dollars. Yea mam every cent of it. Two weeks after baby born see the mother carrin it cross the field fur de old woman what kept all the children and she be going right on wid de hoe all day. When de sun come up the niggers all in the field and workin when de ridin boss come wid de dogs playin long after him. If they didn't chop dat cotton jes right he have em tied up to a stake or a big saplin and beat him till de blood run out the gashes. They come right back and take up whar they lef off work. Two chaps make a hand soon as dey get big nuf to chop out a row.

Had plenty to eat; meat, corncake and molasses, peas and garden stuff. They didn't set out no variety fo the niggers. They had pewter bowls to eat outer and spoons. Eat out in the yard, at the cabins, in the kitchen. Eat different places owin to what you be workin at when the bell rung. Big bell on a high post.

My ma's name was Sina Sutton. She come from Virginia in a nigger traders drove when she was sixteen years old and Miss Frances husband bought er. She had nine childen whut lived. I am de youngest. She died jes before de war broke out. Till that time I had been trained a house girl. My ma was a field hand. Then when the men all went to the army I plowed. I plowed four years I recken, till de surrender. Howd I know it was freedom? A strange woman—I never seed fore, came runnin down where we was all at work. She say loud as she could "Hay freedom. You is free." Everything toe out fer de house and soldiers was lined up. Dats whut they come by fer. Course dey was Yankee soldiers settin the colored folks all free. Everybody was gettin up his clothes and leaving. They didn't know whar des goin. Jes scatterin round. I say give 'em somethin. They was so mad cause they was free and leavin and nobody to work the land. The hogs and stock was mostly all done gone then. White folks sho had been rich but all they had was the land. The smoke houses had been stripped and stripped. The cows all been took off cept the scrubs. Folks plowed ox and glad to plow one.

Sometime we had a good time. I danced till I joined the church. We didn't have no nigger churches that I knowed till after freedom. Go to the white folks church. We danced square dance jess like the white folks long time ago. The niggers baptized after the white folks down at the pond. They joined the white folks church sometimes. The same woman on the place sewed for de niggers, made some things for Miss Frances. I recollects that. She knitted and seed about things. She showed the nigger women how to sew. All the women on the place could card and spin. They sat around and do that when too bad weather to be on the ground. They show didn't teach them to read. They whoop you if they see you have a book. If they see you gang round talkin, they say they talkin bout freedom or equalization. They scatter you bout.

When they sell you, they take you off. See drove pass the house. Men be ridin wid long whips of cow hide wove together and the dogs. The slaves be walkin, some cryin cause they left their folks. They make em stand in a row sometimes and sometimes they put em up on a high place and auction em.

The pore white folks whut not able to buy hands had to work their own land. There shore was a heap of white folks what had no slaves. Some ob dem say theys glad the niggers got turned loose, maybe they could get them to work for them sometimes and pay em.

When you go to be sold you have to say what they tell you to say. When a man be unruly they sell him to get rid of him heap of times. They call it sellin nigger meat. No use tryin run off they catch you an bring you back.

I don't know that there was ever a thought made bout freedom till they was fightin. Said that was what it was about. That was a white mans war cept they stuck a few niggers in front ob the Yankee lines. And some ob the men carried off some man or boy to wait on him. He so used to bein waited on. I ain't takin sides wid neither one of dem I tell you.

If der was anything to be knowed the white folks knowed it. The niggers get passes and visit round on Saturday evening or on Sunday jes mongst theirselves and mongst folks they knowed at the other farms round.

When dat war was done Georgia was jes like being at the bad place. You couldn't stay in the houses fear some Ku Klux come shoot under yo door and bust in wid hatchets. Folks hide out in de woods mostly. If dey hear you talkin they say you talkin bout equalization. They whoop you. You couldn't be settin or standing talkin. They come and ask you what he been tell you. That Ku Klux killed white men too. They say they put em up to hold offices over them. It was heap worse in Georgia after freedom than it was fore. I think the poor nigger have to suffer fo what de white man put on him. We's had a hard time. Some of em down there in Georgia what didn't get into the cities where they could get victuals and a few rags fo cold weather got so pore out in the woods they nearly starved and died out. I heard em talk bout how they died in piles. Niggers have to have meat to eat or he get weak. White folks didn't have no meat, no flour.

The folks was after some people and I run off and kept goin till I took up with some people. The white folks brought them to Tennessee—Covington—I come too. They come in wagons. My father, he got shot and I never seed him no mo. He lived on another farm fo de war. I lived wid them white folks till bout nine years and I married. My old man wanted to come to dis new country. Heard so much talk how fine it was. Then I had run across my brother. He followed me. One brother was killed in the war somehow. My brother liked Memphis an he stayed there. We come on the train. I never did like no city.

We farmed bout, cleared land. Never got much fo the hard work we done. The white man done learned how to figure the black folks out of what was made cept a bare living.

I could read a little and write. He could too. We went to school a little in Tennessee.

When we got so we not able to work hard he come to town and carpentered, right here, and I cooked fo Mr. Hopkins seven years and fo Mr. Gus Thweatt and fo Mr. Nick Thweatt. We got a little ahead then by the hardest. I carried my money right here [bag on a string tied around her waist]. We bought a house and five acres of land. No mum I don't own it now. We got in hard luck and give a mortgage. They closed us out. Mr. Sanders. They say I can live there long as I lives. But they owns it. My garden fence is down and won't nobody fix it up fo me. They promises to come put the posts in but they won't do it and I ain't able no mo. I had a garden this year. Spoke fo a pig but the man said they all died wid the kolerg [cholera]. So I ain't got no meat to eat dis year.

I ain't never had a chile. I ain't got nobody kin to me livin dat I knows bout. When I gets sick a neighbor woman comes over and looks after me.

I thinks if de present generation don't get killed they die cause they too lazy to work. No mum dey don't know nuthin bout work. They ain't got no religion. They so smart they don't pay no tention to what you advise em. I never tries to find out what folks doin and the young generation is killin time. I sho never did vote. I don't believe in it. The women runnin the world now. The old folks ain't got no money an the young ones wastes theirs. Theys able to make it. They don't give the old folks nuthin. The times changes so much I don't know what goiner come next. I jes stop and looks and listens to see if my eyes is foolin me. I can't see, fo de cataracts gettin bad, nohow. Things is heap better now fo de young folks now if they would help derselves. I'm too wo out. I can't do much like I could when I was young. The white folks don't cheat the niggers outen what they make now bad as they did when I farmed.

I never knowed about uprisings till the Ku Klux sprung up. I never heard bout the Nat Turner rebellion. I tell you bout the onliest man I knowed come from Virginia. A fellow come in the country bout everybody called Solomon. Dis long fo the war. He was a free man he said. He would go bout mong his color and teach em fo little what they could slip him along. He teached some to read. When freedom he went to Augusta. My brother seed him and said "Solomon, what you doin here?" and he said "I am er teaching school to my own color." Then he said they run him out of Virginia cause he was learnin his color and he kept going. Some white folks up North learned him to read and cipher. He used a black slate and he had a book he carried around to teach folks with. He was what they called a ginger cake color. They would whoop you if they seed you with books learnin. Mighty few books to get holt of fo the war. We mark on the ground. The passes bout all the paper I ever seed fo I come to Tennessee. Then I got to go to school a little.

Whah would the niggers get guns and shoot to start a uprisin? Never had none cept if a white man give it to him. When you a slave you don't have nothin cept a big fireplace and plenty land to work. They cook on the fireplace. Niggers didn't have no guns fo the war an nuthin to shoot in one if he had one whut he picked up somewhere after the war. The Ku Klux done the uprisin. They say they won't let the nigger enjoy freedom. They killed a lot of black folks in Georgia and a few white folks whut they said was in wid em. We darkies had nuthin to do wid freedom. Two or three set down on you, take leaves and build a fire and burn their feet nearly off. That the way the white folks treat the darky.

I never knowed nobody to hold office. Them whut didn't want to starve got someplace whut he could hold a plow handle. You don't know whut hard times is. Dem was hard times. They used to hide in big cane brakes, nearly wild and nearly starved. Scared to come out. I ain't wanted to go back to Georgia.

The folks I lived wid fo I come to Tennessee, he tanned hides down at the branch and made shoes and he made cloth hats, wool hats. He sold them. We farmed but I watched them up at the house minu a time.

One thing I recollect mighty well. Fo de war a big bellied great monster man come in an folks made a big to do over him. He eat round and laughed round havin a big time. His name was Mr. Wimbeish (?). He wo white britches wid red stripes down the sides and a white shad tail coat all trimmed round de edges wid red and a tall beaver hat. He blowed a bugle and marched all the men every Friday ebening. He come to Miss Frances. They fed him on pies and cakes and me brushin the flies off im and my mouth fairly waterin for a chunk ob de cake. When de first shot of war went off no more could be heard ob old Mr. Wimbeish. He lef an never was heard tell ob no mo. He said never was a Yankee had a hart he didn't understand! I never did know whut he was. He jess said that right smart.

I gets the Old Age Pension and meets the wagon and gets a little commodities. I works my garden and raises a few chickens round my house. I trusts in de Lord and try to do right, honey, dat way I lives.

[TR: Also reported as Maria Sutton Clemments]

"Miss, I don't know a whole heap bout Mr. Wimbeish. I don't know no other name that what they all call him. Some I heard say it like Wimbush. He was a great big man, big in here [chest], big in here [stomach]. He have hair bout color youn [light]. He have big blue eyes jes' sparklin' round over the victuals on the table. He was a lively man. He had a heap to tell and a heap to talk bout. He had fair skin and rosy jaws—full round face. He laughed out loud pretty often. He looked fine when he laughed too. They all was foolish bout him. He was a newcommer in there. I don't know whah he stay. He come down the road regular as Friday come, going to practice em marchin'. Looked like bout fifty fellows. I never seed Mr. Wimbeish on a horse all time he passed long that road. He miter jes' et round mong the people while he stayed there. He wore red 'appletts' on his shoulders. I never seed him outer that fresh starched white suit. It was fishtail coat and had red bands stitched all round the edge and white breetches [britches] [TR: 'britches' is marked out by hand] with red bands down the side. He sure was a young man. They had him bout different places eatin'. Old mistress said, 'Fix up a good dinner today we gwiner have company.' That table was piled full. It was fine eatin'. He say so much I couldn't forgit. Never was a Yankee what have a heart he couldn't understand. I don't know what he was. He was so different. He muster been a Southerner 'cause white folks would not treated him near that good. It was fo de war. They say when the first bugle blowed fo war he was done gone an' nebber been heard of till dis day. I heard some say last they seed him, he was rollin' over an' over on the ground and the men run off to find em nother captain. I don't know if they was tellin' like it took place. I know I never seed him no more.

Slave Times

"The servants take up what they eat in bowls and pans—little wooden bowls—and eat wid their fingers and wid spoons and they had cups. Some had tables fixed up out under the trees. Way they make em—split a big tree half in two and bore holes up in it and trim out legs to fit. They cooked on the fireplaces an' hearth and outerdoors. They cooked sompin to eat. They had plenty to eat. But they didn't have pies and cake less they be goiner have company. They have so much milk they fatten the pigs on it.

"The animals eat up the gardens and crops. The man kill coon and possum if they didn't get nough meat up at the house. I say it sure is good. It is good as pork. The men prowl all night in the winter huntin'. If you be workin' at the field yo dinner is fetched down thar to you in a bucket that high [2 ft.], that big er round [1-1/2 feet wide]. The hands all come an' did they eat. That be mostly fried meat and bread and baked taters, so they could work.

"Old mistress say she first married Mr. Abraham Chenol. Then she married Mr. Joel Sutton and they both died. She had two sons. She had a nephew what come there from way off. She said he was her sister's boy. Couse they had doctors and good ones. Iffen a doctor come say one thing the matter he better stick to it and cure one he come thar to see. Old mistress had three boys till one died. I was brushin' flies offen him. She come and cry and go way cryin'. He callin' her all time. He quit callin' her then he was dead. Made a sorter gurglin' sound. That the first person I seed die. When they say he dead I got out and off I was gone. I was usin' a turkey wing to brush flies offen him. I don't know what was the matter wid em. They buried him on her place whah the grave yard was made. Both her husbands buried down there. She had a fine marble put over his grave. It had things wrote on it. She sent way off an' got it. They hauled it to here in a wagon. The Masons burled him. It was the prettiest sight I ever seed.

"Her son John had some peafowls. She had geese—a big drove—turkeys, guineas, ducks, and geese.

"She had feather beds and wheat straw mattresses, clean whoopee! They used cotton baggin' and straw and some of the servants had a feather bed. Old mistress get up an' go in set till they call her to breakfast. They had a marble top table and a big square piano. That was the parlor furniture. They made rugs outen sheep an' goat skins.

"When she want the cook go wid her she dress her up in some her fine dresses—big white cap like missus slep in an' a white apron tied round her waist. We wore 5¢ calico and gingham dresses for best. She'd buy three and four bolts at Augusta [Georgia] and have it made up to work in. We didn't spin and weave till the war come on. Some old men come round making spinnin' wheels. They was very plain too nearly bout rough. Rich folks had fine silk dresses—jes' rattle when they walked—to wear to preachin'. They sho did have preachin' an' fastin' too durin' the war but folks didn't have fine clothes when it ended like when the war started.

Ku Klux Klan

"It started outener the bushwhackers. Some say they didn't get what was promised em at Shiloh Battle. They didn't get their rights. I don't know what they meant by it. The bushwhackers ketch the men in day goiner work—ketch em this way [by the shoulders or collar]. Such hollerin' and scramblin' then you never heard. They hide behind big pine trees till he come up then step out behind and grab him. They first come an' call fer water. Plenty water in the well or down at the spring. They knowed it too. Then they waste all you had brought up and say—'Ah! First drink I had since I come from hell.' They all knowed ain't nobody come from hell. They had hatchets an' they burst in your house. Jes' to scare you. They shoot under your house. They wore their wives big wide nightgowns and caps and ugliest faces you eber seed. They looked like a gang from hell—ugliest things you ebber did see. It was cold—ground spewed up wid ice and men folks so scared they run out in woods, stay all night. Old mistress died at the close of de war an' her son what was a preacher, he put on a long preacher coat and breeches (britches) [TR: 'britches' is marked out by hand] all black. He put a navy six in his belt and carried carbeen [carbine] on his shoulder. It was a long gun shoot sixteen times. He was a dangerous man. He made the Ku Klux let his folks alone. He walk all night bout his place. He say, 'Forward March!' Then they pass by. He was a dangerous man. So much takin' place all time I was scared nearly to death all time."

[TR: Also reported as Maria Sutton Clemments]

"Missus, I thought if I'd see you agin I'd tell you this song:

'Jeff Davis is President Abe Lincoln is a fool Come here, see Jeff ride the gray horse And Abe Lincoln the mule.'

"They sang all sich songs durin' of the war.

"Five wagons come by. They said it was Jeff Davise's wagons. They was loaded wid silver money—all five—in Lincoln County, Georgia. Somehow the folks got a whiz of it and got the money outen one the wagons. Abraham, my old mistress' son had old-fashion saddle bag full. Sho it was white folks all but two or three slaves. Hogs tore up sacks money, find em hid in the woods. They thought it was corn. They found a leather trunk full er money—silver money—down in the creek. Money buried all round. The way it all started one colored man throwed down a bright dime to a Yankee fo sompin he wanter buy. That started it all. They tied their thumbs this way (thumbs crossed) behind em, then strung em up in trees by their wrists behind em. It put heep of em in bed an' some most died never did get over it. The Yankee soldiers come down that [HW: then?] and got all the money nearly. They say the war last four years, five months. Seemed like twenty years."

"I was born down in Farmerville, Louisiana in the year of 1860. Now my ma lived with some white people, but now the name of the people I do not know. You see, child, I am old and I can't recollect so good. I didn't know my pa cause my ma quit him when I was little. My ma said she worked hard in the field like a black stepchild. My ma had nine chilluns and I was the oldest of the nine. She said her old miss wouldn't let her come to the house to nurse me, so she would slip up under the house and crawl through a hole in the floor. She took and pulled a plank up so she could slip through.

"I would drink any kind of water that I saw if I wanted a drink. If the white folks poured out wash water and I wanted a drink that would do me. It just made me fat and healthy. Most we played was tussling, and couldn't no boy throw me. Nobody tried to whip me cause they couldn't.

"We always cooked on fireplaces and our cake was always molasses cakes. At Christmas time we got candy and apples, but these oranges and bananas and stuff like that wasn't out then. Bananas and oranges just been out a few years. And sugar—we did not know about that. We always used sugar from molasses. I don't think sugar been in session long. If it had I did not get it.

"I got married when I was pretty old, I lived with my husband eight years and he died. I had some children, but I stole them. The biggest work I ever done was farm and we sure worked."

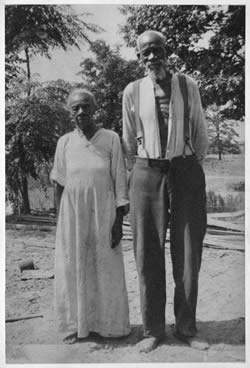

"Uncle Joe" Clinton, on ex-Mississippi slave, lives on a small farm that he owns a few miles north of Marvell, Arkansas. His wife has been dead for a number of years and he has only one living child, if indeed his boy, Joe, who left home fifteen years ago for Chicago and from whom no word has been received since, is still alive. Due to the infirmities of age "Uncle Joe" is unable to work and obtains his support from the income received off the small acreage he rents each year to the Negro family with whom he lives. Seated in an old cane-bottomed chair "Uncle Joe" was dozing in the warm sunshine of on afternoon in early October as I passed through the gate leading into the small yard enclosing his cabin. Arousing himself on my approach, the old Negro offered me a chair. I explained the purpose of my visit and this old man told me the following story:

"I'se now past eighty-six year ole an' was borned in Panola County, Mississippi 'bout three miles from Sardis. My ole mars was Mark Childress, en he sure owned er heap of peoples, womens an' mens bofe, en jus' gangs of chillun. I was real small when us lived in Panola County; how-some-ever I riccolect it well when us all lef' dar and ole mars sold out his land and took us all to de delta where he had bought a big plantation 'bout two or three miles wide in Coahoma County not far from Friar Point. De very place dat my mars bought and dat us moved to is what dey call now, de 'Clover Hill Plantation'. De fust year dat us lived in de delta, us stayed on de place what dey called de 'Swan Lake Place'. Dat place is over dere close to Jonestown and de very place dat Mr. Billy Jones and his son John bought, en dats zackly how come dat town git its name. It was named for Mr. John Jones.

"My mars, Mark Childress, he never was married. He was a bachelor, en I'se tellin' you dis, boss, he was a good, fair man and no fault was to be found wid him. But dem overseers dat he had, dey was real mean. Dey was cruel, least one of them was 'bout de cruelest white man dat I is ever seen. Dat was Harvey Brown. Mars had a nephew what lived with him named Mark Sillers. He was mars' sister's son and was named for my mars. Mr. Mark Sillers, he helped with de runnin' of the place en sich times dat mars 'way from home Mr. Mark, he the real boss den.

"Mr. Harvey Brown, the overseer, he mean sure 'nough I tell you, and de onliest thing that keep him from beatin' de niggers up all de time would be old mars or Mr. Mark Sillers. Bofe of dem was good and kind most all de time. One time dat I remembers, ole mars, he gone back to Panola County for somepin', en Mr. Mark Sillers, he attendin' de camp meeting. That was de day dat Mr. Harvey Brown come mighty nigh killin' Henry. I'll tell you how dat was, boss. It was on Monday morning that it happened. De Friday before dat Monday morning, all of de hands had been pickin' cotton and Mr. Harvey Brown didn't think dat Henry had picked enough cotton dat day en so he give Henry er lashin' out in de field. Dat night Henry, he git mad and burn up his sack and runned off and hid in de canebrake 'long de bayou all of de nex' day. Mr. Harvey, he missed Henry from de field en sent Jeff an' Randall to find him and bring him in. Dey found Henry real soon en tell him iffen he don't come on back to de field dat Mr. Harvey gwine to set de hounds on him. So Henry, he comed on back den 'cause de niggers was skeered of dem wild bloodhounds what they would set on 'em when dey try to run off.

"When Henry git back Mr. Harvey say, 'Henry, where your sack? And how come you ain't pickin' cotton stid runnin' off like dat?' Henry say he done burnt he sack up. Wid dat Mr. Harvey lit in to him like a bear, lashin' him right and left. Henry broke en run den to de cook house where he mammy, 'Aunt Mary', was, en Mr. Harvey right after him wid a heavy stick of wood dat he picked up offen de yard. Mr. Harvey got Henry cornered in de house and near 'bout beat dat nigger to death. In fact, Mr. Harvey, he really think too dat he done kilt Henry 'cause he called 'Uncle Nat' en said, 'Nat, go git some boards en make er coffin for dis nigger what I done kilt.'

"But Henry wasn't daid though he was beat up terrible en they put him in de sick house. For days en days 'Uncle Warner' had to 'tend to him, en wash he wounds, en pick de maggots outen his sores. Dat was jus' de way dat Mr. Harvey Brown treated de niggers every time he git a chanct. He would even lash en beat de wimmens.

"Ole mars had a right good size house in dar 'mongst de quarters where dey kept all de babies en right young chillun whilst dey mammies workin' in de fields pickin' en hoein' time. Old 'Aunt Hannah', an old granny woman, she 'tend to all dem chillun. De chillun's mammies, dey would come in from de fields about three times er day to let de babies suck. Dere was er young nigger woman name Jessie what had a young baby. One day when Jessie come to de house to let dat baby suck, Mr. Harvey think she gone little too long. He give her a hard lashin'.

"Ole mars had a big cook house on de plantation right back in behind he own house en twix his house en de nigger's quarters. Dat was where all de cookin' done for all de niggers on de entire place. Aunt Mary, she de head cook for de mars en all of de niggers too. All of de field hands durin' crop time et dey breakfast en dey dinners in de field. I waited on de table for mars en sort er flunkyed 'round da house en de quarters en de barns, en too I was one of de young darkies what toted de buckets of grub to de field hands.

"Ole mars had a house on de place too dat was called de 'sick house'. Dat was where dem was put dat was sick. It was a place where dey was doctored on en cared for till dey either git well er die. It was er sort er hospital like. 'Uncle Warner', he had charge of de sick house, en he could sure tell iffen you sick er not, or iffen you jus' tryin' to play off from work.

"My pappy, he was named Bill Clinton en my mammy was named Mildred. De reason how come I not named Childress for my mars is 'cause my pappy, he named Clinton when mars git him from de Clintons up in Tennessee somewhere. My mars, he was a good man jus' like I'm tellin' you. Mars had a young nigger woman named Malinda what got married to Charlie Voluntine dat belonged to Mr. Nat Voluntine dat had a place 'bout six miles from our place. In dem days iffen one darky married somebody offen de place where dey lived en what belonged to some other mars, dey didn't git to see one annudder very often, not more'n once a month anyway. So Malinda, she got atter mars to buy Charlie. Sure 'nough he done that very thing so's dem darkies could live togedder. Dat was good in our mars.

"When any marryin' was done 'mongst de darkies on de place in dem days, dey would first hab to ask de mars iffen dey could marry, en iffen he say dat dey could git married den dey would git ole 'Uncle Peyton' to marry 'em. 'Course dere wasn't no sich thing as er license for niggers to marry en I don't riccolect what it was dat 'Uncle Peyton' would say when he done de marryin'. But I 'members well dat 'Uncle Peyton', he de one dat do all of de marryin' 'mongst de darkies.

"My mars, he didn't go to de War but he sure sent er lot er corn en he sent erbout three hundred head er big, fat hogs one time dat I 'members. Den too, he sent somepin like twenty er thirty niggers to de Confedrites in Georgia. I 'members it well de time dat he sent dem niggers. They was all young uns, 'bout grown, en dey was skeered to death to be leavin' en goin' to de War. Dey didn't know en cose but what dey gwine make 'em fight. But mars tole 'em dat dey jus' gwine to work diggin' trenches en sich; but dey didn't want to go nohow en Jeff an' Randall, they runned off en come back home all de way from Georgia en mars let 'em stay.

"Boss, you has heered me tellin' dat my mars was er good, kine man en dat his overseer, Mr. Harvey Brown, was terrible cruel, en mean, en would beat de niggers up every chance he git, en you ask me how come it was dat de mars would have sich a mean man er working for him. Now I'se gwine to tell you de reason. You know de truth is de light, boss, an' dis is de truth what I'se gwine to say. Mars, he in love with Mr. Harvey Brown's wife, Miss Mary, and Miss Mary's young daughter, she was mars' chile. Yas suh, she was dat. She wasn't no kin er tall to Mr. Harvey Brown. Her name was Miss Markis, dats what it was. Mars had done willed dat chile er big part of his property and a whole gang of niggers. He was gwine give her Tolliver, Beckey, Aunt Mary, Austin, an' Savannah en er heap more 'sides dat. But de War, it come on en broke mars up, en all de darkies sot free, en atter dat, so I heered Mr. Harvey Brown en Miss Mary, and de young lady Miss Markis, dey moved up North some place en I ain't never heered no more from dem.

"Mr. Clarke and Mrs. Clarke what de town of Clarksdale is named for, dey lived not far from our place. I knowed dem well. Albert, one of mars' darkies, married Cindy, one of Mr. Clarke's women. General Forrest, I know you is heered of him. I speck he 'bout de bes' general in de War. He sure was a fine looking man en he wore a beard on he face. De general, he had a big plantation down dere in Coahoma County where he would come ever so offen. A lot of times he would come to our place en take dinner wid ole mars, en I would be er waitin' on de table er takin' dem de toddies on de front gallery where dey talkin' 'bout day bizness.

"Boss, you axed me if dey was any sich thing in slavery times as de white men molestin' of de darky wimmen. Dere was a heap of dat went on all de time an' 'course de wimmens, dey couldn't help deyselves and jus' had to put up wid it. Da trouble wasn't from de mars of de wimmens I'se ever knowed of but from de overseers en de outside white folks. Of course all dat couldn't have been goin' on like it did without de mars knowin' it. Dey jus' bound to know dat it went on, but I'se never heered 'bout 'em doin' nothin' to stop it. It jus' was dat way, en dey 'lowed it without tryin' to stop all sich stuff as dat. You know dat niggers is bad 'bout talkin' 'mongst demselves 'bout sich en sich er goin' on, and some of mars' darkies, dey say dat Sam and Dick, what was two real light colored boys, dat us had was mars' chillun. Dat was all talk. I nebber did believe it 'cause dey nebber even looked like mars en he nebber cared no more for dem dan any of the rest of de hands."

"My father belonged to Mr. Ben Martin and my mother and me belonged to the Slaughters. I was small then and didn't know what the war was about, but I remember seein' the Yankees and the Ku Klux.

"Old master had about fifteen or twenty hands but Mr. Martin had a plenty—he had bout a hundred head.

"I member when the war was goin' on we was livin' in Bradley County. We was goin' to Texas to keep the Yankees from gettin' us. I member Mr. Gil Martin was just a young lad of a boy. We got as far as Union County and I know we stopped there and stayed long enough to make two crops and then peace was declared so we cane back to Warren.

"While the war was goin' on, I member when my mother took a note to some soldiers in Warren and asked em to come and play for Miss Mary. I know they stood under a sycamore and two catawba trees and played. There was a perty big bunch of em. Us chillun was glad to hear it. I member just as well as if 'twas yesterday.

"I member when the Yankees come and took all of Miss Mary's silver—took every piece of it. And another time they got three or four of the colored men and made em get a horse apiece and ride away with em bareback. Yankees was all ridin' iron gray horses, and lookin' just as mad. Oh Lord, yes, they rid right up to the gate. All the horses was just alike—iron gray. Sho was perty horses. Them Yankees took everything Miss Mary had.

"After the war ended we stayed on the place one year and made a crop and then my father bought fifty acres of Mr. Ben Martin. He paid some on it every year and when it was paid for Mr. Ben give him a deed to it.

"I'm the only child my mother had. She never had but me, one. I went to school after the war and I member at night I'd be studyin' my lesson and rootin' potatoes and papa would tell us stories about the war. I used to love to hear him on long winter evenings.

"I stayed right there till I married. My father had cows and he'd kill hogs and had a peach orchard, so we got along fine. Our white folks was always good to us."

"Lucy Cotton's my name, and I was born on the tenth day of June, 1865, jist two months after the surrender. No suh, I ain't no kin to the other Cottons around here, so far as I knows. My mother was Jane Hays, and she was owned by a master named Wilson.

"I've belonged to the Holiness Church six years. (They call us 'Holiness,' but the real name is Pentecostal.)

"Yes suh, there's a heap of difference in folks now 'an when I was a girl—especially among the young people. I think no woman, white or black, has got any business wastin' time around the votin' polls. Their place is at home raisin' a family. I hear em sometimes slinging out their 'damns' and it sure don't soun' right to me.

"Good day, mistah. I wish you well—but the gov'ment ain't gonna do nothing. It never has yit."

"I was born close to Indian Bay. I belong to Ed Cotton. Mother was sold from John Mason between Petersburg and Richmond, Virginia. Three sisters was sold and they give grandma and my sister in the trade. Grandma was so old she wasn't much account fer field work. Mother left a son she never seen ag'in. Aunt Adeline's boy come too. They was put on a block but I can't recollect where it was. If mother had a husband she never said nothing 'bout him. He muster been dead.

"Now my papa come from La Grange, Tennessee. Master Bowers sold him to Ed Cotton. He was sold three times. He had one scar on his shoulder. The patrollers hit him as he went over the fence down at Indian Bay. He was a Guinea man. He was heavy set, not very tall. Generally he carried the lead row in the field. He was a good worker. They had to be quiet wid him to get him to work. He would run to the woods. He was a fast runner. He lived to be about a hundred years old. I took keer of him the last five years of his life. Mother was seventy-one years old when she died. She was the mother of twenty-one children.

"Sure, I do remember freedom. After the Civil War ended, Ed Cotton walked out and told papa: 'Rob, you are free.' We worked on till 1866 and we moved to Joe Lambert's place. He had a brother named Tom Lambert. Father never got no land at freedom. He got to own 160 acres, a house on it, and some stock. We all worked and helped him to make it. He was a hard worker and a fast hand.

"I farmed all my life till fifteen years ago I started trucking here in Helena. I gets six dollars assistance from the Sociable Welfare and some little helpouts as I calls it—rice and potatoes and apples. I got one boy fifty-five years old if he be living. I haven't seen him since 1916. He left and went to Chicago. I got a girl in St. Louis. I got a girl here in Helena. I jus' been up to see her. I had nine children. I been married twice. I lived with my first wife thirteen years and seven months. She died. I lived with my second wife forty years and some over—several weeks. She died.

"I was a small boy when the Civil War broke out. Once I got a awful scare. I was perched up on a post. The Yankees come up back of the house and to my back. I seen them. I yelled out, 'Yonder come Yankees.' They come on cussing me. Aunt Ruthie got me under my arms and took me to Miss Fannie Cotton. We lived in part of their house. Walter (white) and me slept together. Mother cooked. Aunt Ruthie was a field hand. Aunt Adeline must have been a field hand too. She hung herself on a black jack tree on the other side of the pool. It was a pool for ducks and stock.

"She hung herself to keep from getting a whooping. Mother raised (reared) her boy. She told mother she would kill herself before she would be whooped. I never heard what she was to be whooped for. She thought she would be whooped. She took a rope and tied it to a limb and to her neck and then jumped. Her toes barely touched the ground. They buried her in the cemetery on the old Ed Cotton place. I never seen her buried. Aunt Ruthie's grave was the first open grave I ever seen. Aunt Mary was papa's sister. She was the oldest.

"I would say anything to the Yankees and hang and hide in Miss Fannie's dress. She wore long big skirts. I hung about her. Grandma raised me on a bottle so mother could nurse Walter (white). There was something wrong wid Miss Fannie. We colored children et out of trays. They hewed them out of small logs. Seven or eight et together. We had our little cups. Grandma had a cup for my water. We et with spoons. It would hold a peck of something to eat. I nursed my mother four weeks and then mama raised Walter and grandma raised me. Walter et out of our tray many and many a time. Mother had good teeth and she chewed for us both. Henry was younger than Walter. They was the only two children Miss Fannie had. Grandma washed out our tray soon as ever we quit eating. She'd put the bread in, then pour the meat and vegetables over it. It was good.

"Did you ever hear of Walter Cotton, a cancer doctor? That was him. He may be dead now. Me and him caused Aunt Sue to get a whooping. They had a little pear tree down twix the house and the spring. Walter knocked one of the sugar pears off and cut it in halves. We et it. Mr. Ed asked 'bout it. Walter told her Aunt Sue pulled it. She didn't come by the tree. He whooped her her declaring all the time she never pulled it nor never seen it. I was scared then to tell on Walter. I hope eat it. Aunt Sue had grown children.

"The Ku Klux come through the first and second gates to papa's house and he opened the door. They grunted around. They told papa to come out. He didn't go and he was ready to hurt them when they come in. He told them when he finished that crop they could have his room. He left that year. They come in on me once before I married. I was at my girl's house. They wanted to be sure we married. The principal thing they was to see was that you didn't live in the house wid a woman till you be married. I wasn't married but I soon did marry her. They scared us up some.

"I don't know if times is so much better for some or not. Some folks won't work. Some do work awful hard. Young folks I'm speaking 'bout. Times is mighty fast now. Seems like they get faster and faster every way. I'll be eighty years old this May. I was born in 1858."

[HW: Escapes on Cow]

"I was born on the tenth of March in some year, I don't know what one. I don't know whether it was in the Civil War or before the Civil War. I forget it. I think that I was born in Vicksburg, Mississippi; I'm not sure, but I think it was.

"My mother was a great shouter. One night before I was born, she was at a meeting, and she said, 'Well, I'll have to go in, I feel something.' She said I was walkin' about in there. And when she went in, I was born that same night.

"My mother was a great Christian woman. She raised us right. We had to be in at sundown. If you didn't bring it in at sundown, she'd whip you,—whip you within an inch of your life.

"She didn't work in the field. She worked at a loom. She worked so long and so often that once she went to sleep at the loom. Her master's boy saw her and told his mother. His mother told him to take a whip and wear her out. He took a stick and went out to beat her awake. He beat my mother till she woke up. When she woke up, she took a pole out of the loom and beat him nearly to death with it. He hollered, 'Don't beat me no more, and I won't let 'em whip you.'

"She said, 'I'm goin' to kill you. These black titties sucked you, and then you come out here to beat me.' And when she left him, he wasn't able to walk.

"And that was the last I seen of her until after freedom. She went out and got on an old cow that she used to milk—Dolly, she called it. She rode away from the plantation, because she knew they would kill her if she stayed.

"My mother was named Luvenia Polk. She got plumb away and stayed away. On account of that, I was raised by my mother. She went to Atchison, Kansas—rode all through them woods on that cow. Tore her clothes all off on those bushes.

"Once a man stopped her and she said, 'My folks gone to Kansas and I don't know how to find 'em.' He told her just how to go.

"My father was an Indian. 'Way back in the dark days, his mother ran away, and when she came up, that's what she come with—a little Indian boy. They called him 'Waw-hoo'che.' His master's name was Tom Polk. Tom Polk was my mother's master too. It was Tom Polk's boy that my mother beat up.

"My father wouldn't let nobody beat him either. One time when somethin' he had did didn't suit Tom Polk—I don't know what it was—they cut sores on him that he died with. Cut him with a raw-hide whip, you know. And then they took salt and rubbed it into the sores.

"He told his master, 'You have took me down and beat me for nothin', and when you do it again, I'm goin' to put you in the ground.' Papa never slept in the house again after that. They got scared and he was scared of them. He used to sleep in the woods.

"They used to call me 'Waw-hoo'che' and 'Red-Headed Indian Brat.' I got in a fight once with my mistress' daughter,—on account of that.

"The children used to say to me, 'They beat your papa yesterday.'

"And I would say to them, 'They better not beat my papa,' and they would go up to the house and tell it, and I would beat 'em for tellin' it.

"There was an old white man used to come out and teach papa how to read the Bible.

"Papa said, 'Ain't you 'fraid they'll kill you if they see you?'

"The old man said, 'No; they don't know what I'm doing, and don't you tell 'em. If you do, they will kill me.'

Signs of the War

"One night my father called me outside and told me that he saw the elements opened up and soldiers fighting in the heavens.

"'Don't you see them, honey?' he said; but I couldn't see them. And he said there was going to be a war.

"I went out and told it. The white people said they ought to take him out and beat him and make him hush his mouth. Because if they got such talk going 'round among the colored people, they wouldn't be able to do nothin' with them. Dr. Polk's wife's father, Old Man Woods, used to say that the niggers weren't goin' to be free. He said that God had showed that to him.

Mean Masters

"Dr. Polk and his son, the one my mother beat up and left lying on the ground, were two mean men. When the slaves didn't pick enough cotton for them, they would take them down the field, and turn up their clothes, till they was naked, and beat them nearly to death.

"Mother was a breeder. While she did that weaving, she had children fast. One day, Tom Polk hit my mother. That was before she ran away. He hit her because she didn't pick the required amount of cotton. When there was nothin' to do at the loom, mother had to go in the field, you know. I forget how much cotton they had to pick. I don't know how many times he hit her. I was small. I heard some one say, 'They got Clarisay Down, down there!' I went to see. And they had her down. She was stout, and they had dug a hole in the ground to put her belly in. I never did get over that. I'm an old woman, but Tom Polk better not come 'round me now even.

"I have heard women scream and holler, 'Do pray, massa, do pray.' And I was sure glad when she beat up young Tom and got away. I didn't have no use for neither one of 'em, and ain't yet.

"It wasn't her work to be in the field. He made her breed and then made her work at the loom. That wasn't nothin'. He would have children by a nigger woman and then have them by her daughter.

"I went out one day and got a gun. I don't know whose gun it was. I said to myself, 'If you whip my mother today, I am goin' to shoot you.' I didn't know where the gun belonged. My oldest sister told me to take it and set it by the door, and I did it.

How Freedom Came

"Dr. Polk had a fine horse. He came riding through the field and said, 'All you all niggers are free now. You can stay here and work for me or you can go to the next field and work.'

"I had an old aunt that they used to make set on a log. She jumped off that log and ran down the field to the quarters shouting and hollering.

"The people all said, 'Nancy's free; they ain't no ants biting her today.' She'd been setting on that log one year. She wouldn't do no kind of work and they make her set there all day and let the ants bite her.

"Big Niggers"

"They used to call my folks 'big niggers.' Papa used to get things off a steamboat. One day he brought a big demi-john home and ordered all the people not to touch it. One day when he went out, I went in it. I had to see what it was. I drunk some of it and when he came home he said to me, 'You've been in that demi-john.' I said, 'No, I haven't.' But he said, 'Yes, you have; I can tell by the way you look.' And then I told him the truth.

"He would get shoes, calico goods, coffee, sugar, and a whole lot of other things. Anything he wanted, he would get. That he didn't, he would ask him to bring the next trip.

"It was a Union gunboat, and ran under the water. You could see the smoke. The white people said, 'That boat's goin' to carry some of these niggers away from here one of these days.'

"And sure enough, it did carry one away.

Buried Treasure and a Runaway

"I went to the big gate one morning and there was a nigger named Charles there.

"I said, 'What you doing out here so early this morning?'

"He said to me, 'You hush yo' mouth and get on back up to the house.'

"I went back to the house and told my mother, 'I saw Charles out there.' That was before my mother ran away.

"My mother said, 'He's fixing to run away. And he's got a barrel of money. And it belongs to the Doctor. 'Cause he and the Dr. went out to bury it to keep the Yankees from getting it.'

"He ran away, and he took the money with him, too. He went out to Kansas City and bought a home. We didn't think much of it, because we knew it was wrong to do it. But Old Master Tom had done a heap of wrong too. He was the first one spotted the boat that morning—Charles was. And he went away on it.

Plenty to Eat

"My father would kill a hog and keep the meat in a pit under the house. I know what it is now. I didn't know then. He would clean the hog and everything before he would bring him to the house. You had to come down outside the house and go into the pit when you wanted to get meat to eat. If my father didn't have a hog, he would steal one from his master's pen and cut its throat and bring it to the pit.

"My folks liked hog guts. We didn't try to keep them long. We'd jus' clean 'em and scrape 'em and throw 'em in the pot. I didn't like to clean 'em but I sure loved to eat 'em. Father had a great big pot they called the wash pot and we would cook the chit'lins in it. You could smell 'em all over the country. I didn't have no sense. Whenever we had a big hog killin', I would say to the other kids, 'We got plenty of meat at our house.'

"They would say back, 'Where you got it?'

"I would tell 'em. And they would say, 'Give us some.'

"And I would say to them, 'No, that's for us.'

"So they called us 'big niggers.'

Marriages Since Freedom

"My first baby was born to my husband. I didn't throw myself away. I married Mr. Cragin in 1867. He lived with me about fifteen years before he died. He got kicked. He was a baker. During the War, he was the cook in a camp. He went to get some flour one morning. He snatched the tray too hard and it kicked him in his bowels. He never did get over it. The tray was full of flour and it was big and heavy. It was a sliding tray. It rolled out easy and fast and you had to pull it careful. I don't know why they called it a kick.

"I married a second husband—if you can call it that—a nigger named Jones. He had a spoonful of sense. We didn't live together three months. He came in one day and I didn't have dinner ready. He slapped me. I had never been slapped by a man before. I went to the drawer and got my pistol out and started to kill him. But I didn't. I told him to leave there fast. He had promised to do a lot of things and didn't do them, and then he used to use bad language too.

Occupation

"I've always sewed for a living. See that sign up there?" The sign read:

ALL KINDS OF BUTTONS SEWED ON

MENDING TOO

"I can't cut out no dress and make it, but I can use a needle on patching and quilting. Can't nobody beat me doin' that. I can knit, too. I can make stockings, gloves, and all such things.

"I belong to Bib Bethel Church, and I get most of my support from the Lord. I get help from the government. I'm trying to get moved, and I'm just sittin' here waiting for the man to come and move me. I ain't got no money, but he promised to move me."

INTERVIEWER'S COMMENT

There it was—the appeal to the slush fund. I have contributed to lunch, tobacco, and cold drinks, but not before to moving expenses. I had only six cents which I had reserved for car fare. But after you have talked with people who are too old to work, too feeble to help themselves in any effective fashion, hemmed up in a single room and unable to pay rent on that, odds and ends of broken and dilapidated furniture, ragged clothes, and not even plenty of water on hand for bathing, barely hanging on to the thread of life without a thrill or a passion, then it is a great thing to have six cents to give away and to be able to walk any distance you want to.

[HW: Whipped from Sunup to Sundown]

"I was born in Hempstead County, between Nashville and Greenville, in Arkansas, on the Military Road. Never been outside the state in my life. I was born ninety years ago. I been here in Pulaski County nearly fifty-seven years.

"I was born in a old double log house chinked and dobbed. Nary a window and one door. I had a bedstead made with saw and ax. Chairs were made with saw, ax, and draw knife. My brother Orange made the furniture. We kept the food in boxes.

"My mother's name was Mandy Bishop, and my father's name was Jerry Bishop. I don't know who my grand folks were. They was all Virginia folks—that is all I know. They come from Virginia, so they told me. My old master was Harmon Bishop and when they divided the property I fell to Miss Evelyn Bishop.

Age

"The first man that came through here writing us up for the Red Cross, I give him my age as near as I could. And they kept that. You know peace was declared in 1865. They told me I was free. I got scared and thought that the speculators were going to put me in them big droves and sell me down in Louisiana. My old mistress said, 'You fool, you are free. We are going to take you to your mammy.' I cried because I thought they was carrying me to see my mother before they would send me to be sold in Louisiana. My old mistress said she would whip me. But she didn't. When we got to my mother's, I said, 'How old is I?' She said, 'You are sixteen.' She didn't say months, she didn't say years, she didn't say weeks, she didn't say days; she just said, 'You are sixteen.' And my case worker told me that made me ninety years old.

"I was in Hempstead County on Harmon Bishop's plantation. It was Miss Polly, Harmon's wife, that told me I was free, and give me my age.

"I know freedom come before 1865, because my brothers would tell me to come home from Nashville where I would be sent to do nursing by my old mistress and master too to nurse for my young mistress.

"When my old master's property was divided, I don't know why—he wasn't dead nor nothin'—I fell to Miss Evelyn, but I stayed in Nashville working for Miss Jennie Nelson, one of Harmon's daughters. Miss Jennie was my young mistress. My brothers were already free. I don't know how Miss Polly came to tell me I was free. But my brothers would see me and tell me to run away and come on home and they would protect me, but I was afraid to try it. Finally Miss Polly found that she couldn't keep me any longer and she come and told me I was free. But I thought that she was fooling me and just wanted to sell me to the speculators.

Family

"My mother was the mother of twenty children and I am the mother of eighteen. My youngest is forty-five. I don't know whether any of my mother's children is living now or not. I left them that didn't join the militia in Hempstead County fifty-seven years ago. Them that joined the militia went off. I don't know nothin' about them. I have two girls living that I know about. I had two boys went to France and I never heard nothin' 'bout what happened to them. Nothing—not a word. Red Cross has hunted 'em. Police Mitchell hunted 'em—police Mitchell in Little Rock. But I ain't heard nothin' 'bout 'em.

Work

"The first work I did was nursing and after that I was water toter. I reckon I was about seven or eight years old when I first began to nurse. I could barely lift the baby. I would have to drag them 'round. Then I toted water to the field. Then when I was put to plowing, and chopping cotton, I don't know exactly how old I was. But I know I was a young girl and it was a good while before the War. I had to do anything that come up—thrashing wheat, sawing logs, with a wristband on, lifting logs, splitting rails. Women in them days wasn't tender like they is now. They would call on you to work like men and you better work too. My mother and father were both field hands.

Soldiers

"Oo-oo-oo-ee-ee-ee!! Man, the soldiers would pass our house at daylight, two deep or four deep, and be passing it at sundown still marching making it to the next stockade. Those were Yankees. They didn't set no slaves free. When I knowed anything about freedom, it was the Bureaus. We didn't know nothing like young folks do now.

"We hardly knowed our names. We was cussed for so many bitches and sons of bitches and bloody bitches, and blood of bitches. We never heard our names scarcely at all. First young man I went with wanted to know my initials! What did I know 'bout initials? You ask 'em ten years old now, and they'll tell you. That was after the War. Initials!!!

Slave Sales

"Have I seen slaves sold! Good God, man! I have seed them sold in droves. I have worn a buck and gag in my mouth for three days for trying to run away. I couldn't eat nor drink—couldn't even catch the slobber that fell from my mouth and run down my chest till the flies settled on it and blowed it. 'Scuse me but jus' look at these places. (She pulled open her waist and showed scars where the maggots had eaten in—ed.)

Whippings

"I been whipped from sunup till sundown. Off and on, you know. They whip me till they got tired and then they go and res' and come out and start again. They kept a bowl filled with vinegar and salt and pepper settin' nearby, and when they had whipped me till the blood come, they would take the mop and sponge the cuts with this stuff so that they would hurt more. They would whip me with the cowhide part of the time and with birch sprouts the other part. There were splinters long as my finger left in my back. A girl named Betty Jones come over and soaped the splinters so that they would be softer and pulled them out. They didn't whip me with a bull whip; they whipped me with a cowhide. They jus' whipped me 'cause they could—'cause they had the privilege. It wasn't nothin' I done; they just whipped me. My married young master, Joe, and his wife, Jennie, they was the ones that did the whipping. But I belonged to Miss Evelyn.

"They had so many babies 'round there I couldn't keep up with all of them. I was jus' a young girl and I couldn't keep track of all them chilen. While I was turned to one, the other would get off. When I looked for that one, another would be gone. Then they would whip me all day for it. They would whip you for anything and wouldn't give you a bite of meat to eat to save your life, but they'd grease your mouth when company come.

Food

"We et out of a trough with a wooden spoon. Mush and milk. Cedar trough and long-handled cedar spoons. Didn't know what meat was. Never got a taste of egg. Oo-ee! Weren't allowed to look at a biscuit. They used to make citrons. They were good too. When the little white chilen would be comin' home from school, we'd run to meet them. They would say, 'Whose nigger are you?' And we would say, 'Yor'n!' And they would say, 'No, you ain't.' They would open those lunch baskets and show us all that good stuff they'd brought back. Hold it out and snatch it back! Finally, they'd give it to us, after they got tired of playing.

Health

"They're burying old Brother Jim Mullen over here today. He was an old man. They buried one here last Sunday—eighty some odd. Brother Mullen had been sick for thirty years. Died settin' up—settin' up in a chair. The old folks is dyin' fas'. Brother Smith, the husband of the old lady that brought you down here, he's in feeble health too. Ain't been well for a long time.

"Look at that place on my head. (There was a knot as big as a hen egg—smooth and shiny—ed.) When it first appeared, it was no bigger then a pea, I scratched it and then the hair commenced to fall out. I went to three doctors, and been to the clinic too. One doctor said it was a busted vein. Another said it was a tumor. Another said it was a wen. I know one thing. It don't hurt me. I can scratch it; I can rub it. (She scratched and rubbed it while I flinched and my flesh crawled—ed.) But it's got me so I can't see and hear good. Dr. Junkins, the best doctor in the community told me not to let anybody cut on it. Dr. Hicks wanted to take it off for fifty dollars. I told him he'd let it stay on for nothin'. I never was sick in my life till a year ago. I used to weigh two hundred ten pounds; now I weigh one hundred forty. I can lap up enough skin on my legs to go 'round 'em twice.

"Since I was sick a year ago. I haven't been able to get 'round any. I never been well since. The first Sunday in January this year, I got worse settin' in the church. I can't hardly get 'round enough to wait on myself. But with what I do and the neighbors' help, I gets along somehow.

Present Condition

"If it weren't for the mercy of the people through here. I would suffer for a drink of water. Somebody ran in on old lady Chairs and killed her for her money. But they didn't get it, and we know who it was too. Somebody born and raised right here 'mongst us. Since then I have been 'fraid to stay at home even.

"I had a fine five-room house and while I was down sick, my daughter sold it and I didn't get but twenty-nine dollars out of it. She got the money, but I never seed it. I jus' lives here in these rags and this dirt and these old broken-down pieces of furniture. I've got fine furniture that she keeps in her house.

"I get some help from the Welfare. They give me eight dollars. They give me commodities too. They give me six at first, and they increased it. My case worker said she would try to git me some more. God knows I need it. I have to pay for everything I get. Have to pay a boy to go get water for me. There's people that gits more 'n they need and have plenty time to go fishin' but don't have no time to work. You see those boys there goin' fishin'; but that's not their fault. One of the merchants in town had them cut off from work because they didn't trade with him.

"You gets 'round lots, son, don't you? Well; if you see anybody that has some old shoes they don't want, git 'em to give 'em to me. I don't care whether they are men's shoes or women's shoes. Men's shoes are more comfortable. I wear number sevens. I don't know what last. Can't you tell? (I suppose that her shoes would be seven E—ed.) I can't live off eight dollar. I have to eat, git help with my washing, pay a child to go for my water, 'n everything. I got these dresses give to me. They too small, and I got 'em laid out to be let out.

"You just come in any time; I can't talk to you like I would a woman; but I guess you can understand me."

Interviewer's Comment

Sallie Crane lives near the highway between Sweet Home and Wrightsville. Wrightsville post office, Lucinda Hays' box. McLain Birch, 1711 Wolfe Street, Little Rock, knows the way to her house.