| VOL. XIII. NO. 360.] | SATURDAY, MARCH 14, 1829. | [PRICE 2d. |

The great Lord Burleigh says, "A realm gaineth more by one year's peace than by ten years' war;" and the architectural triumphs which are rising in every quarter of the metropolis are strong confirmation of this maxim.

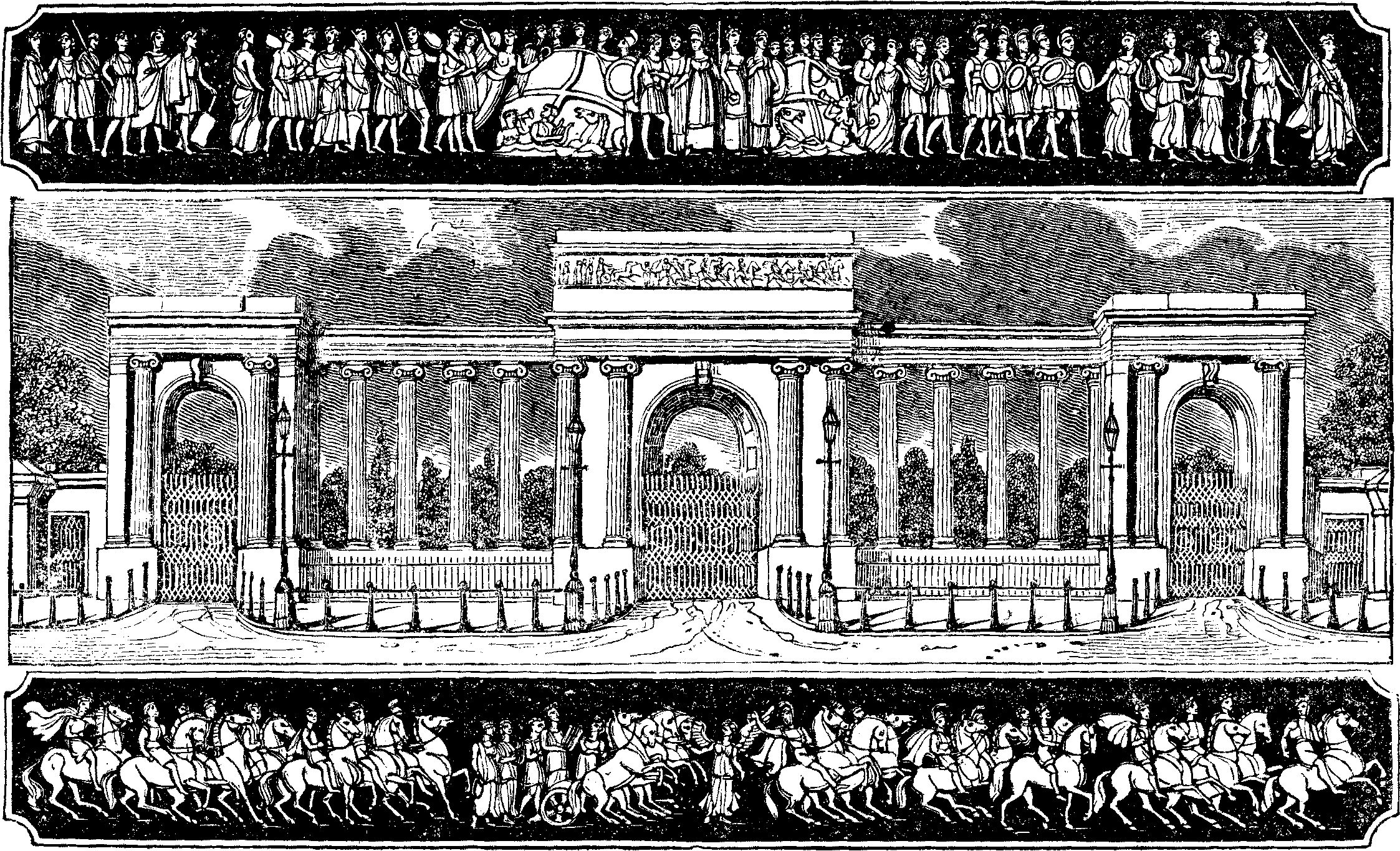

One of these triumphs is represented in the annexed engraving, viz. the grand entrance to Hyde Park, erected from the designs of Decimus Burton, Esq. It consists of a screen of handsome fluted Ionic columns, with three carriage entrance archways, two foot entrances, a lodge, &c. The extent of the whole frontage is about 107 feet. The central entrance has a bold projection: the entablature is supported by four columns; and the volutes of the capitals of the outside column on each side of the gateway are formed in an angular direction, so as to exhibit two complete faces to view. The two side gateways, in their elevations, present two insulated Ionic columns, flanked by antae. All these entrances are finished by a blocking, the sides of the central one being decorated with a beautiful frieze, representing a naval and military triumphal procession, which our artist has copied and represented in distinct engravings. This frieze was designed by Mr. Henning, jun., son of Mr. Henning, so well known for his admirable models of the Elgin marbles. It possesses great classical merit, and the model was exhibited last season in the sculpture-room of the Suffolk-street Gallery.

The gates were manufactured by Messrs. Bramah. They are of iron, bronzed, and fixed or hung to the piers by rings of gun-metal. The design consists of a beautiful arrangement of the Greek honeysuckle ornament; the parts being well defined, and the raffles of the leaves brought out in a most extraordinary manner. The hanging of the gates is also very ingenious.

Mr. Soane's proposed entrances to Piccadilly and St. James's and Hyde Parks, are generally considered superior to those that have been adopted. The park entrances were to consist of two triumphal arches connected with each other by a colonnade and arches stretching across Piccadilly. The same ingenious architect likewise designed a new palace at the top of Constitution Hill, from which to the House of Lords the King should pass Buckingham House, Carlton House, a splendid Waterloo and Trafalgar monument, a fine triumphal arch, the Privy Council Office, Board of Trade, and the new law courts.

On the origin of the application of the name of the "Fleur de Souvenance," (modern "Forget-me-not,") to the Myosotis Scorpiodis.

A gallant knight and a lady bright

Walk'd by a crystal lake;

The twin'd oaks made a grateful shade

Above the fangled brake,

While the trembling leaves of aspen trees

A murmuring music make.

And as they spoke, round them echoes woke

To tales of love and glory;

The knight was brave, though of love the slave,

And the dame lov'd gallant story—

Proudly he told deeds gentle and bold,

Of warriors dead or hoary.

Like babe at rest on its mother's breast,

On that an island lay—

So still and fair reigned Nature there—

So bright the glist'ring spray,

You might have thought the scene had been wrought

By spell of faun or fay.

On the island's edge, midst tangled sedge,

Lay a wreath of wild flow'rs blue—

The broad flag-leaf was their sweet relief,

When the heat too fervid grew;

And the willow's shade a shelter made,

When stormy tempests blew.

And as they stood, the faithful flood

Gave back ev'ry line and trace

Of earth below and heaven above,

And their own forms gallant grace—

For forms more fair than that lovely pair

Ne'er shone on its liquid face.

"I would a flower from that bright bower

Some nymph would waft to me—

For in my eyes a dearer prize

Than glitt'ring gem 'twould be—

For its changeless blue seems emblem true

Of love's own constancy."

The maiden spake, and no more the lake

In slumb'ring stillness lay,

For from the side of his destin'd bride

The knight has pass'd away;

In vain the maid's soft words essay'd

His rash pursuit to stay.

He has reach'd the tower, and pluck'd the flower.

And turn'd from the verdant spot.

Ah, hapless knight! some Naiad bright

Woo'd thee to her coral grot;

And forbids that more to touch that shore

Shall ever be thy lot.

Vainly he tried to gain the side,

Where knelt his lady-love;

Flagg'd every limb, his eyes grew dim,

But still the spirit strove.

One effort more—he flings to shore

The flow'r so dear to prove.

'Tis past! 'tis past! that look his last,

That fond sad glance of love

The bubbling wave his farewell gave

In the moan, "Forget me not."

The above incident occurred in the time of Edward IV.

In the MIRROR, No. 358, the article headed "Memorable Days," the writer, in that part of which the Avver Bread is treated of, says it is made of oats leavened and kneaded into a large, thin, round cake, which is placed upon a girdle over the fire; adding, that he is totally at a loss for a definition of the word Avver; that he has sometimes thought avver, means oaten; which I think, correct, it being very likely a corruption of the French, avoine, oats; introduced among many others, into the Scottish language, during the great intimacy which formerly existed between France and Scotland; in which latter country a great many words were introduced from the former, which are still in use; such as gabart, a large boat, or lighter, from the French gabarre; bawbee, baspiece, a small copper coin; vennell, a lane, or narrow street, which still retains its original pronunciation and meaning. Enfiler la vennel; a common figurative expression for running away is still in use in France. Apropos of vennell, Dr. Stoddard, in a "Pedestrian Tour through the Land of Cakes," when a young man, says he could not trace its meaning in any language, (I speak from memory) also made the same observation where I was; being at that time on intimate terms with the doctor, I pointed out to him its derivation from the Latin into the French, and thence, probably, into the Scotch; the embryo L.L.D. stared, and seemed chagrined, at receiving such information from a

P.S. In no part of Great Britain, I believe, is oaten bread so much used as in Scotland; from whence the term, "The Land of Cakes is derived." In some parts of France, Pain d'avoine has been in use in my time.

The first Crusade1 to the Holy Land was undertaken by numerous Christian princes, who gained Jerusalem after it had been in possession of the Saracens four hundred and nine years. Godfrey, of Boulogne, was then chosen king by his companions in arms; but he had not long enjoyed his new dignity, before he had occasion to march out against a great army of Turks and Saracens, whom he overthrew, and killed one hundred thousand of their men, besides taking much spoil. Shortly after this victory, a pestilence happened, of which multitudes died; and the contagion reaching Godfrey, the first Christian King of Jerusalem, he also expired, on the 18th of July, 1100, having scarcely reigned a full year.

Godfrey's successors, the Baldwins, defeated the Turks in many engagements. In the reign of Baldwin III., however, the Christians lost Edessa, a circumstance which affected Pope Eugenius III. to such a degree, that he prevailed on Conrad III., Emperor of Germany, to relieve his brethren in Syria. In the year 1146, therefore, Conrad marched through Greece, and soon afterwards encountered the Turkish army, which he routed; he then proceeded to Iconium, the principal seat of the Turks in Lesser Asia; but, for want of provisions and health, was compelled to relinquish his design of taking that city, and to return home. Much about the same period, Lewis VIII., of France, made an expedition to the Holy Land, but was wholly unsuccessful in his attempts against the enemy. Notwithstanding these failures, King Baldwin, relying on his own strength, gained possession of Askalon, and defeated the Turks in numerous actions. Previous to his death, which was caused by poison, in 1163, he was the victorious sovereign of Jerusalem and the greatest part of Syria.

During the reign of Baldwin IV., Saladin, Sultan of Egypt, invaded Palestine, and took several towns, notwithstanding the valour of the Christians. In the succeeding reign of King Guy, however, the Christians, still unfortunate, received a decisive blow, which tended to the decline of their independence in the Holy Land; for, among other places of importance, Saladin made a capture of Jerusalem, and took its king prisoner. When the conqueror entered the holy city, he profaned every sacred place, save the Temple of the Sepulchre, (which the Christians redeemed with an immense sum of money,) and drove the Latin Christians from their abodes, who were only allowed to carry what they could hastily collect on their backs, either to Tripoly, Antioch, or Tyre, the only three places which then remained in the Christians' possession. All the monuments were demolished, except those of our Saviour, King Godfrey, and Baldwin I.2 The city was yielded to the [pg 164] captors on the 2nd of October, 1187, after the Christians had possessed it about eighty-nine years.

These calamitous transactions in Palestine greatly alarmed all Europe, and several princes speedily resolved to oppose the career of the oppressors, and to leave no means untried of regaining the kingdom of Jerusalem. In furtherance of this design, the Emperor Frederic marched into Palestine with a powerful army, and defeated the Turks near Melitena; he afterwards met them near Comogena, where he also routed them, but was unhappily killed in the action. Some time after this, King Philip, of France, and Richard I., of England, engaged in a crusade for the relief of the Christians. Philip arrived first, and proceeded to Ptolemais, which King Guy, having obtained his liberty, was then besieging. King Richard, in his passage, was driven with his fleet upon the coast of Cyprus, but was not permitted to land; this so highly offended him, that he landed his whole army by force, and soon over-ran the island. He was at length opposed by the king of Cyprus, whom he took prisoner, and carried in chains to Ptolemais, where he was welcomed with great rejoicings by the besiegers, who stood in much need of assistance. It would he superfluous to relate here the particulars of the siege; let it suffice to say, that after a general assault had been given, a breach was made, so that the assailants were enabled to enter the city, which Saladin surrendered to them upon articles, on the 12th of July, 1191. King Richard here obtained the title of Coeur de Lion, for having taken down Duke Leopold's standard, that was first fixed in the breach, and placed his own in its stead.

After the taking of Ptolemais, King Philip and many other princes returned home, leaving King Richard in Palestine to prosecute the war in concert with Guy, whom Richard, in a short time afterwards, persuaded to accept of the crown of Cyprus, in lieu of his pretences to Jerusalem. By these crafty means, Richard caused himself to be proclaimed King of Jerusalem; but while he was preparing to besiege that city, he received news that the French were about to invade England. He was therefore compelled to conclude a peace with Saladin, not very advantageous to Christendom, and to return to Europe. But meeting with bad weather, he was driven on the coast of Histria; and, while endeavouring to travel through the country in the habit of a templar, was taken prisoner by Duke Leopold, of Austria, who became his enemy at the siege of Ptolemais. The duke sold him for forty thousand pounds to the emperor, Henry VI., who soon afterwards had a hundred thousand pounds for his ransom.

About the same period, Sultan Saladin, the most formidable enemy the Christians ever encountered, died; an event which caused Pope Celestine to prevail on the emperor, Henry VI., of Germany, to make a new expedition against the Turks, who were in consequence defeated; but the emperor's general, the Duke of Saxony, being killed, and the emperor himself dying soon afterwards, the Germans returned home without accomplishing the object of their expedition. They had no sooner departed than the Turks, in revenge, nearly drove the Christians from the Holy Land, and took all the strong towns which the Crusaders had gained, excepting Tyre and Ptolemais. In 1199, a fleet was fitted out at the instigation of Pope Innocent III. against the infidels. On this occasion, the Christians, notwithstanding their strenuous exertions, failed of taking Jerusalem, though several other important places were delivered to them.

In the year 1228, Frederic, Emperor of Germany, set out from Brundusium to Palestine, took Jerusalem, which the enemy had left in a desolate condition, and caused himself to be proclaimed king. But, after this conquest, he was obliged to return to his own country, where his presence was required. The Turks immediately assembled a prodigious army for regaining the Holy City, which they ultimately took, putting the German garrison to the sword, in the year 1234; since which time, the Christian powers, weary of these useless expeditions, have made no considerable effort to possess it.

The Christians were entirely driven from Palestine and Syria in the year 1291, about one hundred and ninety-two years after the capture of Jerusalem by Godfrey of Boulogne.

The empty passions of the angry world,

The loves of heroes, the despair of maids,

The rage of kings, of beggars and of slaves,

Shakspeare alone attun'd to song.—The rest essay'd.

Laureate of bards! thyself unsung

Would stamp us reckless.

Popes.

Clement V., 1305.

John XXII., 1316.

Emperor of the East.

Andronicus II., 1283.

Emperors of the West.

Albert I., 1278.

Henry VII., 1308.

Frederic III., 1314.

France.

Philip IV., 1285.

Louis X., 1314.

Charles IV. 1322.

Scotland. Robert Bruce, 1306.

Popes.

John XXII., 1316.

Benedict XII., 1334.

Clement VI., 1342.

Innocent VI., 1352.

Urban V., 1362.

Gregory XI., 1370.

Emperors of the East.

Andronicus II., 1283.

Andronicus III., 1332.

John V., 1341.

John VI., 1355.

Emperors of the West.

Frederic III., 1314.

Louis IV., 1330.

Edward Baliol, 1332.

David II. (again), 1342.

Charles IV., 1347.

Robert II., 1370.

France.

Charles IV., 1322.

Philip VI., 1328.

John I., 1355.

Charles V., 1364.

Scotland.

Robert Bruce, 1306.

David II., 1330.

Edward Baliol, 1332.

David II. (again), 1342.

Robert II., 1370.

Popes.

Gregory XI., 1370.

Urban VI., 1378.

Boniface IX., 1389.

Emperors of the East.

John VI., 1355.

Emanuel II., 1391.

Emperors of the West.

Charles IV., 1347.

Weneslaus, 1378.

France.

Charles V., 1364.

Charles VI., 1380.

Scotland.

Robert II., 1370.

Robert III., 1390.

Popes.

Boniface IX., 1389.

Innocent VII., 1404.

Emperors of the West.

Weneslaus, 1378.

Popes.

Gregory XII. 1406.

Alexander V. 1409.

John XXIII. 1410.

Emperor of the East.

Emanuel II., 1391.

Emperors of the West.

Robert le Pet, 1400.

Sigismund, 1410.

France.

Charles VI., 1380.

Scotland.

Robert III., 1390.

Popes.

John XXIII. 1410.

Martin V., 1417.

Emperor of the East.

Emanuel II., 1391.

Emperor of the West.

Sigismund, 1410.

France.

Charles VI., 1380.

Charles VII. 1422.

Scotland.

Robert III., 1390.

Popes.

Martin V., 1417.

Eugenius IV. 1431.

Nicholas V., 1447.

Galixus III. 1455.

Pius II., 1458.

Emperors of the East.

Emanuel II., 1391.

John VII., 1426.

Constantine III.,

last emperor 1448.

Emperors of the West.

Sigismund, 1410.

Albert II., 1438.

Frederic IV., 1440.

France.

Charles VII. 1422.

Louis XI., 1440.

Scotland.

Robert III., 1390.

James I., 1424.

James II., 1437.

James III., 1440.

Popes.

Pius II., 1458.

Paul II., 1464.

Sixtus IV., 1471.

Emperor of the West.

Frederic IV., 1440.

France.

Louis XI., 1440.

Scotland.

James III., 1440.

Popes.

Innocent VIII., 1484.

Alexander VI. 1492.

Pius III., 1593.

Julius II., 1503.

Emperors of Germany.

Frederic IV., 1440.

Maximilian I. 1493.

France.

Charles VIII. 1485.

Louis XII., 1498.

Scotland.

James III., 1460.

James IV., 1489.

Popes.

Julius II., 1503.

Leo X., 1513.

Adrian VI., 1521.

Clement VII. 1523.

Paul III., 1534.

Emperors of Germany.

Maximilian I. 1493.

Charles V., 1519.

France.

Louis XII., 1498.

Francis I., 1515.

Henry II., 1547.

Scotland.

James IV., 1489.

James V., 1514.

Mary, 1542.

Popes.

Paul III., 1534.

Julius III., 1550.

Emperor of Germany.

Charles V., 1519.

France.

Henry II., 1547.

Scotland.

Mary, 1542.

Popes.

Julius III., 1550.

Marcellus II. 1555.

Paul IV., 1555.

Emperors of Germany.

Charles V., 1519.

Ferdinand, 1556.

Popes.

Paul IV., 1555.

Pius IV., 1559.

Pius V., 1565.

Gregory XIII., 1572.

Sixtus V., 1585.

Urban VII., 1590.

Gregory XIV., 1590.

Emperors of Germany.

Ferdinand I., 1556.

Maximilian II. 1564.

Rodolphus II. 1576.

France.

Henry II., 1547.

Francis II., 1559.

Charles IX., 1560.

Henry III., 1574.

Henry IV., 1589.

Popes.

Innocent IX. 1501.

Clement VIII., 1592.

Scotland.

Mary, 1542.

James VI., 1567.

Popes.

Clement VIII., 1592.

Leo IX., 1605.

Paul III., 1605.

Gregory XV. 1621.

Urban VIII. 1623.

Emperors of Germany.

Rodolphus II. 1576.

Matthias I., 1612.

Ferdinand III. 1619.

France.

Henry IV., 1589.

Louis XIII., 1610.

Spain & Portugal.

Philip III., 1507.

Philip IV., 1620.

Denmark.

Christian IV. 1588.

Sweden.

Sigismund, 1592.

Charles IX., 1606.

Gustavus II. 1611.

Popes.

Urban VIII. 1623.

Innocent X., 1644.

Emperors of Germany.

Ferdinand II. 1619.

Ferdinand III. 1637.

France.

Louis XIII., 1610.

Louis XIV., 1643.

Spain & Portugal.

Philip IV., 1620.

Portugal only.

John IV., 1640.

Denmark.

Christian IV. 1583.

Frederic III. 1648.

Sweden.

Gustavus II. 1611.

Christiana, 1633.

Popes.

Innocent X., 1644.

Alexander VII., 1655.

Emperors of Germany.

Ferdinand III., 1637.

Leopold I., 1658.

France.

Louis XIV., 1643.

Spain.

Philip IV., 1620.

Portugal.

John IV., 1640.

Alonzo VI., 1656.

Denmark.

Frederic III. 1646.

Sweden.

Christiana, 1633.

Charles X., 1653.

*** The remainder of this very useful Tablet, which has been compiled by a Correspondent, expressly for our pages, will be found in the Supplement published with the present No.

An old ship companion of mine was a native of the Gold Coast, and was of the Diana species. He had been purchased by the cook of the vessel in which I sailed from Africa, and was considered his exclusive property. Jack's place then was close to the cabooce; but as his education progressed, he was gradually allowed an increase of liberty, till at last he enjoyed the range of the whole ship, except the cabin. I had embarked with more than a mere womanly aversion to monkeys, it was absolute antipathy; and although I often laughed at Jack's freaks, still I kept out of his way, till a circumstance brought with it a closer acquaintance, and cured me of my dislike. Our latitude was three degrees south, and we only proceeded by occasional tornadoes, the intervals of which were filled up by dead calms and bright weather; when these occurred during the day, the helm was frequently lashed, and all the watch went below. On one of these occasions I was sitting alone on the deck, and reading intently, when, in an instant, something jumped upon my shoulders, twisted its tale round my neck, and screamed close to my ears. My immediate conviction that it was Jack scarcely relieved me: but there was no help; I dared not cry for assistance, because I was afraid of him, and dared not obey the next impulse, which was to thump him off, for the same reason, I therefore became civil from necessity, and from that moment Jack and I entered into an alliance. He gradually loosened his hold, looked at my face, examined my hands and rings with the most minute attention, and soon found the biscuit which lay by my side. When I liked him well enough to profit by his friendship, he became a constant source of amusement. Like all other nautical monkeys, he was fond of pulling off the men's caps as they slept, and throwing them into the sea; of knocking over the parrots' cages to drink the water as it trickled along the deck, regardless of the occasional gripe he received; of taking the dried herbs out of the tin mugs in which the men were making tea of them; of dexterously picking out the pieces of biscuit which were toasting between the bars of the grate; of stealing the carpenter's tools; in short, of teasing every thing and every body: but he was also a first-rate equestrian. Whenever the pigs were let out to take a run on deck, he took his station behind a cask, whence he leaped on the back of one of his steeds as it passed. Of course the speed was increased, and the nails he stuck in to keep himself on, produced a squeaking: but Jack was never thrown, and became so fond of the exercise, that he was obliged to be shut up whenever the pigs were at liberty. Confinement was the worst punishment he could receive, and whenever threatened with that, or any other, he would cling to me for protection. At night, when about to be sent to bed in an empty hencoop, he generally hid himself under my shawl, and at last never suffered any one but myself to put him to rest. He was particularly jealous of the other monkeys on board, who were all smaller than himself, and put two out of his way. The first feat of the kind was performed in my presence: he began by holding out his paw, and making a squeaking noise, which the other evidently considered as an invitation; the poor little thing crouched to him most humbly; but Jack seized him by the neck, hopped off to the side of the vessel, and threw him into the sea. We cast out a rope immediately, but the monkey was too frightened to cling to it, and we were going too fast to save him by any other means. Of course, Jack was flogged and scolded, at which he was very penitent; but the deceitful rogue, at the end of three days, sent another victim to the same destiny. But his spite against his own race was manifested at another time in a very original way. The men had been painting the ship's side with a streak of white, and upon being summoned to dinner, left their brushes and paint on deck. Unknown to Jack, I was seated behind the companion door, and saw the whole transaction; he called a little black monkey to him, who, like the others, immediately crouched to his superior, when he seized him by the nape of the neck with one paw, took the brush, dripping with paint, with the other, and covered him with white from head to foot. Both the man at the helm and myself burst into a laugh, upon which Jack dropped his victim, and scampered up the rigging. The unhappy little beast began licking himself, but I called the steward, who washed him so well with turpentine, that all injury was prevented; but during our bustle Jack was peeping with his black nose through the bars of the maintop, apparently enjoying the confusion. For three days he persisted in remaining aloft; no one could catch him, he darted with such rapidity from rope to rope; at length, impelled by hunger, he dropped unexpectedly from some height on my knees, as if for refuge, and as he had [pg 168] thus confided in me, I could not deliver him up to punishment.

The only way in which I could control his tricks was by showing him to the panther on board, which excited his fears very strongly. I used to hold him up by his tail, and the instant he saw the panther he would become perfectly stiff, shut his eyes, and pretend to be dead. When I moved away, he would relax his limbs, and open one eye very cautiously; but if he caught a glimpse of the panther's cage, the eyes were quickly closed, and he resumed the rigidity of death. After four months' sojourn together, I quitted Jack off the Scilly Islands, and understood that I was very much regretted: he unceasingly watched for me in the morning, and searched for me in every direction, even venturing into the cabin; nor was he reconciled to my departure when my servants left the vessel at Gravesend.—Mag. Natural History.

It must be owned that such a little book as this has long been wanted; for of all writing, that relating to the stage is the most diffuse. It is scattered about in biography, criticism and anecdote, not unfrequently of great interest, but occupying so much "valuable" time, that to condense it, or to pick the wheat from the chaff, is no trifling task. So much for the amusement which our "Companion" may yield to the Londoner: his utility as a cicerone or guide will be more obvious to our country friends, who flock in thousands to see and hear comedy and tragedy at this play-going season. A young girl comes to town to see "the lions," and, with her "cousin," goes to the opera, where one guinea is paid for their admission, or even more if they be installed. Two Londoners would buy their tickets during the day, and thus pay but 17s. Another party are dying to hear Braham sing, or Paton warble her nightingale notes among the canvass groves and hollyhock gardens of Drury Lane and Covent Garden; or to sup on the frowning woes of tragedy, the intrigues of an interlude dished up as an entremet, or a melodrama for a ragout; or the wit and waggery of a farce, sweet and soft-flowing like a petit-verre, to finish the repast. They go, and between the acts try to count the wax and gas, the feet, and foot lights till they are purblind; they return home and dream of Desdemona, sing themselves to sleep with the notes of the last song, are haunted with the odd physiognomy of Liston, and repeat the farce-laugh till the dream is broken. Next day it is mighty pleasant to read how many hundred people the theatre will hold, how many pounds they all paid to get there; and how the splendid pile of Drury Lane rose on the area of a cockpit: and how Garrick played Macbeth in a court suit, and John Kemble enacted the sufferings of Hamlet in powdered hair. Upon all these subjects the Companion is conversant, although he does not set up for Sir Oracle, or shake his head like Burleigh. In short, he tells of "many things," from the cart of Thespis and the Roman theatres, with their 6,000 singers and dancers, to the companies on the present stages.

Thus, we have the Origin of the Drama—Rise of the Drama in England—Early English Theatres—Descriptions of all the London Theatres—and a pleasant chapter on the Italian Opera. The Appendix contains pithy chronologies of the dramatists and actors, bygone and contemporary—origin of all the varieties of the drama—the topography of the stage and scenery, costume—expenses of the theatres—masquerades—play-bills and editions of plays, and a host of theatrical customs. In truth, the book is as full as the tail of a fine lobster, and will doubtless repay the time and research which its preparation must have occupied. There is also a, frontispiece of the fronts of the twelve London Theatres.

Mr. James Jennings has favoured us with a copy of his Ornithologia; or the Birds, a poem; with copious Notes; &c. The latter portion is to us the most interesting, especially as it contains an immense body of valuable research into the history and economy of birds, in a pleasant, piquant, anecdotical style, without any of the quaintness or crabbedness of scientific technicality. Mr. Jennings's volume is therefore well adapted for presentation to young persons; whilst the knowledge which it displays, entitles it to a much higher stand than a mere book of amusement. To illustrate what we have said in its praise, the reader will find in the Supplement to the present Number, two or three of the most attractive Notes under "THE NATURALIST," which likewise contains Three Engravings of very curious subjects in other departments of Natural History.

We have already spoken in favourable terms of this volume. It consists of 15 conversations of a family circle, [pg 169] comprising a familiar explanation of the Huttonian and Wernerian systems; the Mosaic geology, as explained by Penn; and the late discoveries of Buckland, Humboldt, Macculloch, and others. By way of specimen, we take a portion of a conversation which introduces the very interesting subject of the formation of coal:

Edward.—As the Huttonians evidently fail in proving coal to be produced by fusion, I hope the Wernerians may succeed better, for I should be sorry if so interesting a subject were left unexplained.

Mrs. R.—To understand their account, it will be requisite for you to recollect the process of the formation of bogs and marshes, as it is from these that Werner derives coal. What I told you, also, of the change produced on wood by being long exposed to moisture and kept from contact with the air, will be of use here, as wood, in all stages of change, is often found in coal-fields, in the same way as in peat-bogs.

Edward. That is a very strong circumstance in favour of the alleged origin.

Mrs. R. There are some facts, indeed, connected with this, which prove this origin beyond question, as you will admit, when I tell you that specimens of wood are often found partly converted into coal and partly unchanged, or petrified by some other mineral.

Edward. This will, at least, be direct proof that wood may be converted into coal.

Mrs. R. One instance of this kind is mentioned by Brand, in his "History of Newcastle," as having been brought from Iceland, by Sir Joseph Banks. Dr. Rennie, in his "Essay on Peat Moss," gives a still stronger example. In the parish of Kilsyth, he tells us, there was found, in a solid bed of sandstone, the trunk of a tree in an erect position, the indentations of the bark and marks of the branches being in many parts of it still obvious. It rose from a bed of coal below the sandstone, and the roots which reached the coal, as well as the bark for an inch thick round the trunk, were completely converted into coal, while the centre consisted of sandstone. This specimen I have myself seen in the parsonage garden of Kilsyth, and this description is most accurate. Sir George Mackenzie lately found a specimen precisely similar, in the face of a sandstone rock in Lothian, and I have seen numerous specimens of bamboos and reeds in the sandstone quarries of Glasgow, with the bark converted into coal, and the centre filled with sandstone.

Edward.—But would not this prove that sandstone, also, was derived from wood?

Mrs. R.—No: it would only prove that the centre had been destroyed and removed; for the sandstone is not chemically composed of vegetable substances, but the coal is.

Edward—Still, I cannot conceive by what process the conversion is effected.

Mrs. R. By a natural process, evidently; being a continuation of that which converts mosses and marshes into peat. Nay, it is supposed not to stop at the formation of coal, but, by a continuation of the causes, the coal becomes jet, and even amber. The eminent chemist, Fourcroy, in proof of this, mentions a specimen in which one end was wood, little changed, and the other pure jet; and Chaptal tells us, that at Montpellier there are dug up whole cart-loads of trees converted into jet, though the original forms are so perfectly preserved that he could often detect the species; and, among others, he mentions birch and walnut. What is even more remarkable, he found a wooden pail and a wooden shovel converted into pure jet.

Edward. Then I suppose, from all these details, that coal might be formed artificially, by imitating the natural process.

Mrs. R. Mr. Hatchett made many ingenious and successful experiments with this design, and Dr. Macculloch has more recently succeeded in actually making coal. One of the strongest instances of the process, is the existence of a great quantity of wood only half converted into coal, at Bovey, near Exeter; this has been much discussed by the geologists; but there is a bed of coal found at Locle, on the continent, which is said to have been formed almost within the memory of man, though I have not yet seen any good account of it.

Altogether, we have been much gratified with these Conversations. As a hint, en passant, we remind the editor of such an oversight as that at p. 350-1, "Order in which the strata lies in the Paris basin."

There were many newspapers in the room, but there was nothing in them. There was a clock, but it did not seem to go; at least, so he thought, but after looking at it for a very long time he found it did go, but it went very slowly. Then he looked at his watch, and that went as slow as the clock. Then he took up the newspapers again one after the other very deliberately. He read the sporting intelligence and the fashionable news. But he did not read very attentively, as he afterwards discovered. Then he looked at the clock [pg 170] again, and was almost angry at the imperturbable monotony of its face. Then he took out his pocket-book to amuse himself by reading his memorandums, but they were very few, and very unintelligible. Then he rose up from his seat, and went to the window; and looked at the people in the street; he thought they looked very stupid, and wondered what they could all find to do with themselves. He looked at the carriages, and saw none with coronets, except now and then a hackney-coach. Then he began to pick his teeth, and that reminded him of eating; and then he rang the bell, which presently brought a waiter; and he took that opportunity of drawling out the word "waiter" in such lengthened tone, as if resolved to make one word last as long as possible.—Rank and Talent.

"For every battle of the warrior is with confused noise and garments rolled in blood but this with burning and fuel of fire."—ISAIAH ix. 5.

From Gilgal's camp went forth, at dead of night,

The host of Israel: with the rising sun

They stood arrayed against the Amorite,

Beneath the regal heights of Gibeon,

Glorious in morning's splendour! Lebanon,

Dim in the distance, reared its lofty head;

Light clouds o'erbung the vale of Ajalon,

And the Five Armies, by their monarchs led,

Not to mere mortal fight, but conflict far more dread.

How beautiful, at matin's early prime,

Valley, and mountain, and that city fair!

Magnificent, yet fearfully sublime,

In few brief hours the scene depicted there!

Below the battle raged, and high in air

The gathering clouds, with tempest in their womb,

A supernatural darkness seem'd to wear;

As heralding, by their portentous gloom,

Victory to Israel's host, her foes' impending doom!

Upon a jutting crag, below the height

Where stands the royal city in its pride,

The ark is rested! in the people's sight

The priests and Joshua standing by its side;

Awhile the chief the sea of battle eyed,

Which heaved beneath:—in accents undismayed,

"Sun, stand thou still on Gibeon!" he cried,

"And thou, O Moon, o'er Ajalon be stayed!"

And holiest records tell the mandate was obeyed.

Look on the horrid conflict; mark the stream

Of lurid and unnatural light that falls,

Like some wild meteors bright terrific gleam,

On Gibeon's steep and battlemented walls;

Her royal palace, and her pillared halls,

Seeming more gorgeous in its vivid blaze!

While o'er proud Lebanon the storm appals,

In jagged lines the arrowy lightning plays,

Soften'd to Israel's sight by intervening haze.

But o'er the Amoritish camp the cloud

Bursts in its fury! on the race abhorred

The parting heavens, as from a pitchy shroud.

Their desolating hail-storm's wrath out-poured,

More vengeful in its ire than Israel's sword!

Thus was deliverance unto Gibeon shown;

And by the fearful battle of the Lord,

The army of the Amorites o'erthrown,

And the almighty power of Israel's God made known.

Made known by marvels awfully sublime!

Yet far more glorious in the Christian's sight

Than these stern terrors of the olden time,

The gentler splendours of that peaceful night,

When opening clouds display'd, in vision bright,

The heavenly host to Bethlehem's shepherd train,

Shedding around them more than cloudless light!

"Glory to God on high!" their opening strain,

Its chorus, "Peace on earth!" its theme Messiah's reign!

What could be more natural than for Mr. Jackson to say to Dr. Smith, "I am going to call on Markham?" And what could be more natural than for Dr. Smith to say, "I will go with you, and you may introduce me?" So then Markham's friend, Jackson, leaves his card, and Jackson's friend, Dr. Smith, leaves his card too.—Rank and Talent.

We read much of the luxurious effeminacy of the old Romans, their fantastically curled hair, their favourite robes, &c.; but what will posterity think of some of the modes of puppyism in our times, when they read in a chronicle of fashion, dated 1829, that gentlemen wore elegant drab cloth opera manteaux lined with scarlet velvet, and confined at the collar with a gold chain! In another dress, the waistcoat is directed to be made of "a very beautiful white embroidered velvet;" "some young men have appeared at balls with blue dress gloves embroidered with white;" "the system of the cravat is to form the organization of linen on the breast," the very "march" of foppery; "cloaks of the gentlemen lined with plush silk of celestial blue;" "at balls our young exquisites sport pocket-handkerchiefs of fine lawn, with a hem as broad as their thumbs; the corners only are embroidered:" "shoes tied with a small rosette;" "a young gentleman now suffers his hair to grow, has it curled, and parted on the left side of the forehead," &c. &c.—This out-herods Herod.

A new edition of this very useful and attractive volume has just appeared, re-edited by Mr. Britton, who, by his extensive architectural knowledge, as well as by his popular style of imparting that knowledge, is calculated to produce a better "Picture of London" than any other writer within our acquaintance. The introduction is, of course, the most novel part of this edition, and as it enables Mr. Britton to embody much authentic information on the public works now in progress, we have abridged a few of these [pg 171] details, which will be found in a Supplement published with the present Number. The Picture of London was, we believe, first printed in 1806; and the extensive patronage which it has enjoyed during twenty-two years has been well deserved by its progressive completeness.

In our last volume we devoted nearly six of our columns to an outline of the predecessor of the present work, or the novel of Penelope. We there stated our opinion of the author's talents in a peculiar style of novel-writing—a sort of mixture of satire and fashion, without the starchness of the one, or the silly affectation of the other—abounding in well-drawn pictures of real life, free from caricature, and teeming with home-truths, in themselves of such plainness and ready application, as to make precept and example follow on with near approaches to probability and truth.

The author's forte unquestionably lies in this species of writing, and his "Rank and Talent" will, we think, bear us out in this opinion. The story or canvass of the novel is simple, and well prepared for his sketches and finished portraits of character. They belong to fashionable and middle life, and the conceits and eccentricities, as well as the straightforward integrity of their stations are illustrated with peculiar force. Sound moral and knowledge of the world are occasionally introduced with great tact, for the author is no stranger to the inmost workings and recesses of the human heart; and he adapts these lessons, and dovetails them with the narrative, in a clever and agreeable style.

The outline of the story may be briefly told. The Hon. Philip Martindale has an action brought against him, at the assizes, for the false imprisonment of one Richard Smith, as a poacher; although the object of the defendant was a beautiful girl residing with the defendant. Clara Rivolta is rudely cross-examined as a witness; whilst the plaintiff's case is conducted by Horatio Markham, an intelligent young barrister, whose parents reside in the town where the action is tried. The cousin of the defendant, Mr. John Martindale, an eccentric old gentleman who builds an abbey for his titled relative to occupy, whilst he himself lives in a cottage on the estate; seeks an acquaintance with Markham. These parties reside at Brigland, and Philip Martindale, a dissipated lover of the turf, who is dependent on his capricious cousin for his supplies; and Horatio Markham, the hero, are thus introduced. Then we have a country curate of the higher order, together with his loquacious half; which are excellent portraits.

John Martindale is one of those eccentric beings—half-aristocrat, and half-liberal, which are more rare in society than they were fifty years since; and upon this curious compound turns the narrative. Clara Rivolta and her mother, Signora Rivolta, the wife of Colonel R. quit their native Italy, and visit Brigland, where old Martindale, on the discovery, acknowledges the Signora as the fruit of an early imprudence on the continent, and finally leaves them a large fortune. Clara is married to Markham, and Philip Martindale, afterwards Earl of Trimmerstone, marries a gay, giddy girl, who elopes with a perfumed puppy of the first fragrance.

The round of the earl's dissipation is but a sorry picture of the prostitution of rank; but the connexion leads us into a succession of scenes of fashionable life, which are vividly drawn, as are two or three of their adjuncts,—a popular west-end preacher, an anti-nervous physician, the dandy already mentioned, a noble gambler, and a rich city knight and his aspiring family—all of which are to the life.

Our extracts must be detached from the narrative; but they may serve to illustrate the felicitous vein in which the characters are drawn.

The means by which Signora Rivolta is discovered by Martindale, is well managed. One morning after the old gentleman had been amusing his visiters with some Italian views, Mr. Denver, the curate, introduced to Mr. Martindale with great parade Colonel Rivolta, whom he described as having recently made his escape from the continent, where he was exposed to persecution, if not to death, on account of his political opinions. The reverend gentleman then proceeded to state, that the colonel had previously to his own arrival in England sent over his wife and daughter, whom he had committed to the care of Richard Smith; that with them he had also transmitted some property, which old Richard had invested for their use and benefit; that unfortunately the very first night of the colonel's arrival at [pg 172] Brigland, the cottage in which Richard Smith dwelt had been robbed by a gipsy; that in consequence of that event the poor old man had been so seriously alarmed, that he had been totally unable to attend to any thing, and that he had died, leaving this poor foreigner in a strange land not knowing how to proceed as to the recovery of his little property. After an interview, in which Martindale promises the colonel his assistance, the latter was rising to take leave, when his eye was arrested by a print which Mr. Martindale held in his hand, and which he had unrolled while he was talking. As soon as the colonel saw the picture, he recognised the scene which it represented, and uttered an ejaculation, indicative of surprise and pleasure. Mr. Martindale then, for the first time, observed the print, and noticed its subject; he also looked upon it with surprise, but not with pleasure; and then he asked the stranger if that scene were familiar to him, with very great emotion the colonel replied:—"That scene brings to my recollection the happiest day of my life."

For a few seconds the party were totally silent; for the clergyman and the foreigner were struck dumb with astonishment at the altered looks of the old gentleman, and were surprised to see him crushing the picture in both hands. He then, as if with an effort of great resolution, exclaimed:—"And it brings to my recollection the most miserable day of my life."

The agitation of the old gentleman abated, and he replied: "I thank you for your kindness, sir, but my sorrow arises from self-reproach. I have inflicted injuries which can never be redressed." He hesitated, as if wishing, but dreading to say more. Then changing the tone of his voice, as if he were about to speak on some totally different subject, he continued addressing himself to Colonel Rivolta:—"I presume, sir, you are a native of Genoa, or you are very familiar with that city." "I was born," replied the foreigner, "at Naples; but very early in life I was removed to Genoa, that I might be engaged in merchandize; for my patrimony was very small, and my relations would have despised me, had I endeavoured by any occupation to gain a livelihood in my native city." "Then you were not originally destined for the army?" "I was not; but after I had been some few years in Genoa, I began to grow weary of the pursuits of merchandize, and indeed to feel some of that pride of which I had accused my relations, and I thought that I should be satisfied with very little if I might be free from the occupation of the merchant; and while I was so thinking, I met by chance an old acquaintance who persuaded me to undertake the profession of arms, to which I was indeed not reluctant. And so I left my merchandise, and did not see Genoa again for nearly two years. It was then that I was so much interested in that scene which the picture portrays; for in a very small house which is in the same street, directly opposite to that palace, there lived an old woman, whose name was ——"

The attention of the old gentleman had been powerfully arrested by the commencement of the Italian's narrative; and he listened very calmly till the narrator arrived at the point when he was about to mention the name of the old woman who lived opposite to the palace in question: then was Mr. Martindale again excited, and without waiting for the conclusion of the sentence, interrupted it by exclaiming: "Ah! what! do you know that old woman? Is she living? Where is she?—Stop—no—let me see—impossible!—Why I must be nearly seventy—yes—are you sure? Is not her name Bianchi?"

To this hurried and confused mass of interrogation, the colonel replied that her name was Bianchi; but that she had died nearly twenty years ago, at a very advanced age, being at the time of her death nearly ninety years of age. Hearing this, the old gentleman assumed a great calmness and composure of manner, though he trembled as if in an ague; and turning to the astonished clergyman, who was pleasing himself with the anticipation of some catastrophe or anecdote which might form a fine subject for town-talk, he very deliberately said:—"Mr. Denver, I beg I may not intrude any longer on your valuable time. This gentleman, I find, can give me some account of an old acquaintance of mine. The inquiries may not be interesting to you. Make my best compliments to Mrs. Denver."

When this good man was withdrawn, Mr. Martindale requested the stranger to be seated; and unmindful of the guests whom he had left to amuse themselves and each other, he commenced very deliberately to examine the foreigner concerning those matters which had so strongly excited his feelings.

"You tell me," said Mr. Martindale, "that the old woman, Bianchi, has been dead nearly twenty years. Now, my good friend, can you inform me how long you were acquainted with this old woman before her death." "I knew her," replied the colonel, "only for about four years [pg 173] before she died." "And had you much intimacy with her, so as to hear her talk about former days." "Very often indeed," replied the foreigner, "did she talk about the past; for as her age was very great, and her memory was very good, it was great interest to hear her tell of ancient things; and she was a woman of most excellent understanding, and very benevolent in her disposition. Indeed, I can say that I loved the old woman much, very much indeed. I was sorry at her death." "But tell me," said Mr. Martindale, impatiently, "did you ever hear her say any thing of an infant—an orphan that was committed to her care nearly forty years ago?" At this question, the eyes of the stranger brightened, and his face was overspread with a smile of delight, when he replied: "Oh yes, much indeed, much indeed! that orphan is my wife,"

This rapidity of explanation was almost too much for the old gentleman's feelings. His limbs had been trembling with the agitation arising from thus reverting to days and events long passed; and he had entertained some hope from the language of the foreigner, that he might gain some intelligence concerning one that had been forgotten, but whose image was again revived in his memory. He had thought but lightly in the days of his youth of that which he then called folly, but more seriously in the days of his age of that same conduct which then he called vice. It would have been happiness to his soul, could an opportunity have been afforded him of making something like amends to the representatives of the injured, even though the injured had been long asleep in the grave. When all at once, therefore, the intelligence burst upon him, that one was living in whom he possessed an interest, and over whose destiny he should have watched, but whom he had neglected and forgotten, he felt his soul melt within him; and well it was for him that he found relief in tears. Surprised beyond measure was Colonel Rivolta, when he observed the effect produced on Mr. Martindale, and heard the old gentleman say with trembling voice:—"And that orphan, sir, is my daughter." He paused for a minute or two, and his companion was too much astonished and interested to interrupt him: recovering himself, he continued: "For many years after that child was born, I had not the means of making any other provision for it than placing it under the care of the old woman of whom we have been speaking. I gave her such compensation as my circumstances then allowed; and as the mother died soon after the birth of the infant, I thought myself freed from all farther responsibility when I had made provision for the infant. I endeavoured, indeed, to forget the event altogether; and as I wished to form a respectable connexion in marriage, I took especial care to conceal this transgression. However, various circumstances prevented me from time to time from entering into the married state; and having within the last twelve years come into the possession of larger property than I had ever anticipated, it occurred to me that there should be living at Genoa a child of mine, then indeed long past childhood. I wrote to Genoa, and had no answer; I went to Genoa, and could find no trace either of my child or of the old woman to whose care I had entrusted her; and I was grieved not so much for the loss of my child, as for the lack of an opportunity of making some amends for my crime. I am delighted to hear that she lives. To-morrow I will see her."

Upon this interesting disclosure hinge the principal incidents. In the course of these are some admirable pleasantries; especially a horse-race, and the description of Trimmerstone, in vol. i.; and the clerical prig, and a slight sketch of the dangle Tippetson, in vol. ii.

The Earl of Trimmerstone's portrait, after old Martindale's death is well drawn:

The Earl of Trimmerstone was depressed in spirits; it is indeed very natural that he should be. The life which he had led, the companions with whom he had associated, the disappointments which he had experienced, his foolish marriage, the disgraceful conduct of his silly countess, the taunts and reproaches of his opulent relative, the weariness and disgust that he felt in having nothing to do, and the annoyance of an empty title, which merely mocked him with the epithet of right honourable, all these things combined to render him almost disgusted with, and weary of life. His solitude was soon invaded by a visit from the Rev. Marmaduke Sprout, rector of Trimmerstone, who was rather fanatical in his theology, and finical in attire and address. He could presently render himself agreeable to any person of exalted rank by his very courteous and conciliating demeanour; and he possessed a peculiar softness and gentleness of manner, with which indeed the Earl of Trimmerstone would, in his past days of cock-fighting, horse-racing, and boxing, have been thoroughly disgusted. But his lordship was quite an altered man. Formerly, the lowest pursuits under the name of sport or fancy had been agreeable to his lordship; and [pg 174] every species of religious sentiment he had regarded with the profoundest contempt and the most unmingled abhorrence. But now he was sick, and weary of all these things! and because one extreme was purely offensive and wearisome, he took it for granted that the opposite must be truly delightful and highly consistent, and so under the tuition of Mr. Sprout, he changed and reversed all his habits, good, bad, and indifferent. From staking thousands at a horse-race, he turned up his eyes at the grievous abomination of half-crown whist; and, indeed, had he been disposed to card-playing, he could not have indulged himself at Trimmerstone, for Mr. Sprout had banished almost all card-playing from the place, so that there was not a pack of cards in the parish, except two or three mutilated well-thumbed packs of quadrille-cards, which were still used by a knot of antiquated spinsters worthy of the good old days of Sacheverel and High Church. Quadrille-cards will not do for whist, for all the eights, nines, and tens are thrown out. Formerly, Lord Trimmerstone used to be proud of giving some of his acquaintance a sumptuous dinner; but now he had changed all that, and he only kept one female cook, who could just manage to make a comfortable and snug little dish or two for his lordship's own self, occasionally assisted by the Rev. Mr. Sprout. Formerly, his lordship had been disposed to be lively, and oftentimes facetious; but now he was prodigiously grave, and almost sulky. Formerly, his lordship never went to church; now he went twice every Sunday, and said Amen as loud as the clerk, and with much more solemnity, for the clerk did not turn up his eyes for fear of losing the place. Formerly, his lordship had been very candid; now he had become exceedingly censorious, and he seemed to measure his religion by the severity with which he reproved transgressors. His lordship several times attempted to make all the inhabitants of Trimmerstone go to church twice every Sunday, except his own cook. But in this his lordship could not succeed, and indeed it was well for him that he could not; for if he had, the church would have been so crowded that he could not have enjoyed a great, large, lined, stuffed, padded, carpeted pew for himself.

In another portion of the MIRROR we have quoted half a dozen of the author's amenities just to show the reader that in depicting the follies of fashionable life, there is less fiddle-faddle—less rank than talent—and more sense than in many other chronicles of the ton.

When you travel in a stage-coach, make all the passengers, both inside and outside, fully acquainted with your name, business, and objects in travelling, before five minutes have elapsed. Among the rest, be sure you give them to think you are a man of property, and the personal friend of at least half-a-dozen nobles or members of parliament. If in trade, inform them you have something very handsome in the three per cents., and live on terms of perfect familiarity with the great Jew.

Honesty is the best and most profitable policy in the long run, but there are a thousand exceptions to this rule in private practice.

Do no charity by stealth; it is never repaid in this world to any advantage; do it openly, and there are chances of its returning cent per cent.

You may keep a running horse, or two, though you are a magistrate sworn to put down gambling: you need not bet upon the race-course yourself. You may subscribe to Fishmongers' Hall, and go there without throwing the dice. You may share the profits of a roulette table, without venturing your luck. It is strange that vulgar understandings cannot discriminate in these matters!

When you have made up your mind finally to do any thing, ask the advice of your friend about it. The act of consultation will please him, and you will be none the worse.

Human happiness is more or less complete in a ratio with successful pecuniary accumulation.

If you enter a drawing-room before dinner a little time too early, and find yourself vis-à-vis with an unlucky visiter as forlorn as yourself, do not utter a word. The chances are, nine out of ten, he will not speak first, that is, if he be a true Briton. Stare at him as hard as you can.

If you meet a lady in society, old or young, married or single, who equals you in argument, or rises superior to the thousand and one automatons disgorged monthly from fashionable boarding-schools, report her a bas bleu to your male acquaintances, and warn her own sex to shun her.

When you meet an inferior in a public street, it is your duty to cut him, if any one who knows you is in sight. If you cannot escape a recognition, do it with as little parade as possible—a movement of the lips is sufficient—and walk on at a [pg 175] quick rate. Who knows but the Lord Mayor, or Mr. Alderman Blowbladder, may observe you?

A grain of impudence will fetch more in the market than twelve bushels of modesty.

In the scale of dignities two Cheapside chaises make one Stanhope; two Stanhopes a cab; two cabs a landaulet and pair; and so on up to the state-coach; and as their numerical relation, so is the degree of respect they may justly exact.

If you visit foreign parts, and meet a countryman who may be useful to you, do not hesitate to avail yourself of his services; but be sure never to acknowledge him should you meet in your native land, unless he receive some other introduction to you, and you have it on creditable evidence that he is a man of good property.

Never allow reason weight in any thing you have resolved to be right that is opposed to it. Reason may be useful in mathematics, to men of genius, and to scholars; but it has little to do with every-day existence, with the Three per Cents, the national revenue, the Stock Exchange, or the India House.

Never get acquainted with your next-door neighbour, unless you find he is in good pecuniary circumstances. If you meet on the highway, or touch elbows at your respective fore-doors, look at each other like two strange tom-cats, and pursue your way.

Commiserate the fate of a Thurtell, a Probert, or a Corder, sent (ripened for heaven in a forty-eight hours' probation by a Newgate chaplain) out of the world their hellish acts have so sullied; but sympathise not with a Riego or a Canaris. Heroic vice was always spiriting; heroic virtue is phlegmatic. John Bull's constitution is only acted upon by strong excitement.

When you dine with the Lord Mayor, or any of the Aldermen of Brobdignag, and they attempt to exhibit their skill at repartee, be sure decide the wealthiest to be the wittiest. It will insure you a good dinner another time, perhaps something more.

In choosing a wife, prefer even Bristol ugliness to beauty, especially if there be a fortune. Beauty will change, intellect may be too much for you, but ugliness will be true to you as to itself; besides its advantage of preserving you from the effects of conjugal frailty.

A judge's wig is a Delphic mystery, whether brains be in it or not. It is a of sublunary wisdom—an umbrella over an oracle.

When you dine at a public dinner, always take your seat opposite a favourite dish. Carve it yourself, and select the choicest bits, then leave it to your right-hand neighbour to help the rest of the company.

Always stick your napkin in your button-hole at the dinner table, if you admit such French superfluities at all. Eat with the sharp edge of your knife towards your mouth; forks won't take up gravy. Never wipe your lips when you take wine with a lady, and fill both her glass and your own until daylight is not visible through the crystal.

When Mrs. Bull is obstreperous, go to the coffee-house and call for your glass. It is an excellent cure for her complaint, and you will get the latest news retailed in the most engaging manner, with the pleasure of knowing she is biting her lips at home in vexation.

Never hold any intercourse with people of whom the world speaks ill. 'Tis true they may be, and generally are, among the very best of mankind, but as they are not reputed to be so, what is that to you?

Some persons cant about the wickedness of the times: believe them not; this is the most saintly of ages, the most pure of generations, considering its temptations.

Vice at the east and west end of town, is different only in form; in substance it comes to the same thing, and in quality is equal to a grain.

Never leave a dispute to be settled by arbitration; if you are rich, always appeal to law, especially if your opponent be poor. The lawyers will manage for you long before the case gets up to the Lords, and perhaps secure your rival in banco regis for expenses. In an arbitration, the case may be decided against you in a twinkling. It is a capital thing that justice and a long purse are sworn brothers; besides, moneyed men should have some advantage in society.

So little is the value of an oath understood by any but the Bull family, that none but the postboys and the vulgar use oaths in foreign nations, America excepted; but that country being a chip of the old block, already rivals honest John; outdo him she must not.

Lard your butter, wet your tobacco, pipe-clay your flour, sand your sugar, sloe-leaf your tea, coal-ash your pepper, deteriorate your drugs, water your liquors, alloy your gold and silver, plunder your lodgers, and, while none know it, who is the worse! Then to church, and thank God you are not as other men.

Live and talk as if you were to live for ever. If you have accumulated tens [pg 176] of thousands, try and make them hundreds of thousands. Why should you retire and make way for the industry of others, while you are able to treasure up more.

Give credit, take credit, live upon credit; if you are wealthy, your own money will be gathering interest at the same time. If you are poor, you have no other means to live by.

In matters of business, let there be no favour. If you are dealing with your own father, give nothing to him. Screw the uttermost farthing, and, if need, sell him.

Give only to receive.

Men of genius are fools; the truly great men know how to make money, and money is power—the power of making more money. Your men of genius are at best but harlequins with empty pockets.—New Monthly Magazine.

A snapper up of unconsidered trifles.

SHAKSPEARE.

Swift, in his Journal to Stella, speaking of the Opera says, "In half an hour I was tired of their fine stuff."

FAUSTINA and CUZZONI, two celebrated opera singers, were such bitter rivals, that neither of them would sing in the same room with the other.

Four learned cats are now exhibiting in Regent-street; but as we have not yet left our card with their feline excellencies, we cannot wink at their perfections.

The officers of Sherwood Forest, famous for having been the head-quarters of Robin Hood in the 16th century, were a warden, his lieutenant and steward, a bow-bearer, and a ranger, four verderers, twelve regarders, four agisters, and twelve keepers or foresters, all under a chief forester; besides these there were several woodwards for every township within the forest, and one for every principal wood.

The late Duke of Norfolk passing down Piccadilly with Sheridan, as a gigantic wooden Highlander was just then fixing at the door of a tobacconist, asked, what was the reason of this usual location. "Ay, ay, I see it now," said the duke, "it is as much as to say, bargains here, a man may get the most for his farthing." "No," said Sheridan, "it seems quite the contrary, for if the Scotchman could have driven any thing in the way of bargain, he would have gone in."

A Mrs. Tomlinson is mentioned in the papers as having, lately died, worth thirty thousand pounds, chiefly amassed by habits of extreme penury. She had, before this accumulation, separated from her husband, to whom she handsomely allowed five shillings a-week. This was observed to realize the often-repeated saying of Solomon—"A virtuous woman is a crown to her husband."

The compiler of a Catechism of Chemistry up to the latest date, says, "It is a remarkable fact, that a pound of rags may be converted into more than a pound of sugar, merely by the action of sulphuric acid. When shreds of linen are triturated (stirred) in a glass mortar with sulphuric acid, they yield a gummy matter on evaporation; and if this matter be boiled for some time with dilute sulphuric acid, we obtain a crystallizable sugar."—Now is the time to look up all your old rags, &c.

A choral society, consisting of 160 members, has just been established at Breslau, for the cultivation of ancient music.

There is a curious tradition respecting the estate of Sutton Park, (the seat of Sir J. Burgoyne.) near Biggleswade, Bedfordshire, which states it formerly belonged to John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, who gave it to an ancestor of the present proprietor, named Roger Burgoyne, by the following laconic grant:—

I, John of Gaunt,

Do give and do grant

To Roger Burgoyne,

And the heirs of his loin,

Both Sutton and Potton,3

Until the world's rotten.

There is also a moated site in the park, called "John of Gaunt's Castle."

With the present Number is published a SUPPLEMENT, containing THREE ENGRAVINGS: 1. The Death-Watch. 2. The Glow-Worm. 3. The Talipot Tree, and a series of other curious and attractive Wonders of Nature—The First and Last Crime, a vivid and masterly sketch—Public Improvements now in progress in London—besides an unusual variety of Literary Novelties.

Printed and Published by J. LIMBIRD 143, Strand, (near Somerset House,) London; sold by ERNEST FLEISCHER, 626, New Market, Leipsic; and by all Newsmen and Booksellers.

Footnote 1: (return)An account of the original instigator of the Crusades will be found in vol. viii. of the MIRROR, page 232.

Footnote 2: (return)The Turks generally show some regard to real piety and valour.

Footnote 3: (return)A neighbouring village.