This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Mary at the Farm and Book of Recipes Compiled during Her Visit among the "Pennsylvania Germans"

Author: Edith M. Thomas

Release Date: September 27, 2004 [eBook #13545]

[Last updated: October 21, 2021]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MARY AT THE FARM AND BOOK OF RECIPES COMPILED DURING HER VISIT AMONG THE "PENNSYLVANIA GERMANS"***

AND

BOOK OF RECIPES

COMPILED DURING HER

VISIT AMONG THE

"PENNSYLVANIA GERMANS"

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

1915

We love our Pennsylvania, grand old Keystone State;

Land of far famed rivers, and rock-ribbed mountains great.

With her wealth of "Dusky Diamonds" and historic valleys fair,

Proud to claim her as our birthplace; land of varied treasures rare.

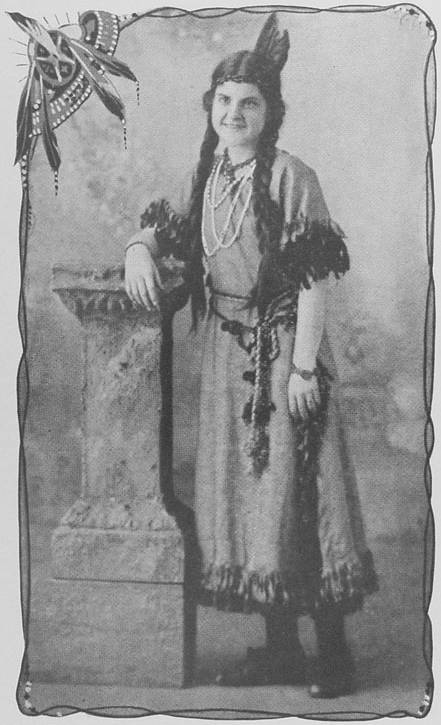

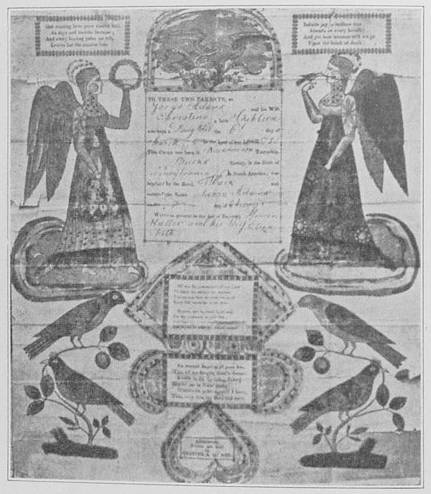

The incidents narrated in this book are based on fact, and, while not absolutely true in every particular, the characters are all drawn from real life. The photographs are true likenesses of the people they are supposed to represent, and while in some instances the correct names are not given (for reasons which the reader will readily understand), the various scenes, relics, etc., are true historically and geographically. The places described can be easily recognized by any one who has ever visited the section of Pennsylvania in which the plot (if it can really be called a plot) of the story is laid. Many of the recipes given Mary by Pennsylvania German housewives, noted for the excellence of their cooking, have never appeared in print.

THE AUTHOR.

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO MY FRIENDS WITH GRATITUDE FOR THEIR MANY HELPFUL KINDNESSES.

"HE WHO HAS A THOUSAND FRIENDS, HAS NEVER A ONE TO SPARE."

MARION WILEY.

One morning in early spring, John Landis, a Pennsylvania German farmer

living in Schuggenhaus Township, Bucks County, on opening his mail

box, fastened to a tree at the crossroads (for the convenience of

rural mail carriers) found one letter for his wife Sarah, the envelope

addressed in the well-known handwriting of her favorite niece, Mary

Midleton, of Philadelphia.

One morning in early spring, John Landis, a Pennsylvania German farmer

living in Schuggenhaus Township, Bucks County, on opening his mail

box, fastened to a tree at the crossroads (for the convenience of

rural mail carriers) found one letter for his wife Sarah, the envelope

addressed in the well-known handwriting of her favorite niece, Mary

Midleton, of Philadelphia.

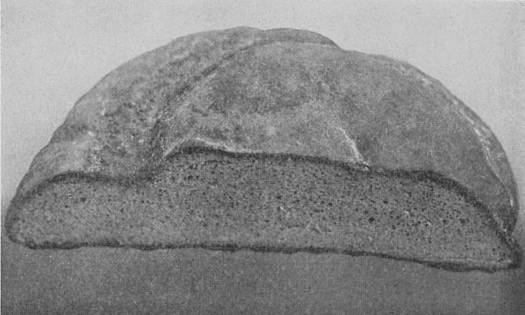

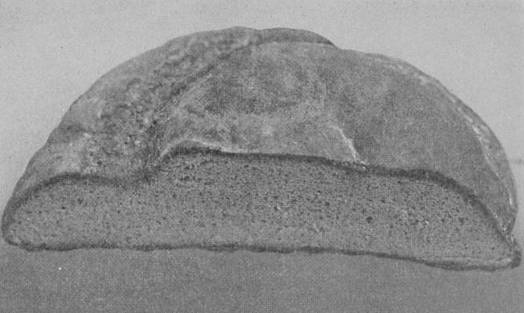

A letter being quite an event at "Clear Spring" farm, he hastened with it to the house, finding "Aunt Sarah," as she was called by every one (Great Aunt to Mary), in the cheery farm house kitchen busily engaged kneading sponge for a loaf of rye bread, which she carefully deposited on a well-floured linen cloth, in a large bowl for the final raising.

Carefully adjusting her glasses more securely over the bridge of her nose, she turned at the sound of her husband's footsteps. Seeing the letter in his hand she inquired: "What news, John?" Quickly opening the letter handed her, she, after a hasty perusal, gave one of the whimsical smiles peculiar to her and remarked decisively, with a characteristic nod of her head: "John, Mary Midleton intends to marry, else why, pray tell me, would she write of giving up teaching her kindergarten class in the city, to spend the summer with us on the farm learning, she writes, to keep house, cook, economize and to learn how to get the most joy and profit from life?"

"Well, well! Mary is a dear girl, why should she not think of marrying?" replied her husband; "she is nineteen. Quite time, I think, she should learn housekeeping—something every young girl should know. We should hear of fewer divorces and a less number of failures of men in business, had their wives been trained before marriage to be good, thrifty, economical housekeepers and, still more important, good homemakers. To be a helpmate in every sense of the word is every woman's duty, I think, when her husband works early and late to procure the means to provide for her comforts and luxuries and a competency for old age. Write Mary to come at once, and under your teaching she may, in time, become as capable a housekeeper and as good a cook as her Aunt Sarah; and, to my way of thinking, there is none better, my dear."

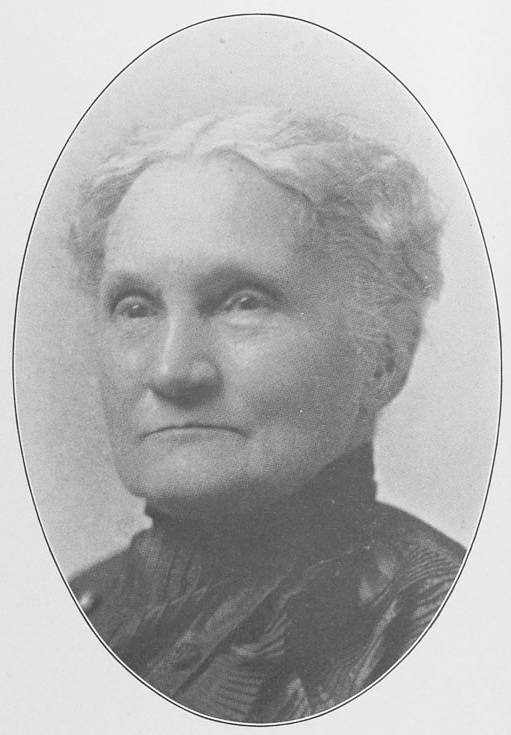

Praise from her usually reticent husband never failed to deepen the tint of pink on Aunt Sarah's still smooth, unwrinkled, youthful looking face, made more charming by being framed in waves of silvery gray hair, on which the "Hand of Time," in passing, had sprinkled some of the dust from the road of life.

In size, Sarah Landis was a little below medium height, rather stout, or should I say comfortable, and matronly looking; very erect for a woman of her age. Her bright, expressive, gray eyes twinkled humorously when she talked. She had developed a fine character by her years of unselfish devotion to family and friends. Her splendid sense of humor helped her to overcome difficulties, and her ability to rise above her environment, however discouraging their conditions, prevented her from being unhappy or depressed by the small annoyances met daily. She never failed to find joy and pleasure in the faithful performance of daily tasks, however small or insignificant. Aunt Sarah attributed her remarkably fine, clear complexion, seldom equalled in a woman of her years, to good digestion and excellent health; her love of fresh air, fruit and clear spring water. She usually drank from four to five tumblerfuls of water a day. She never ate to excess, and frequently remarked: "I think more people suffer from over-eating than from insufficient food." An advocate of deep breathing, she spent as much of her time as she could spare from household duties in the open air.

Sarah Landis was not what one would call beautiful, but good and whole-souled looking. To quote her husband: "To me Sarah never looks so sweet and homelike when all 'fussed up' in her best black dress on special occasions, as she does when engaged in daily household tasks around home, in her plain, neat, gray calico dress."

This dress was always covered with a large, spotlessly clean, blue gingham apron of small broken check, and she was very particular about having a certain-sized check. The apron had a patch pocket, which usually contained small twists or little wads of cord, which, like "The Old Ladies in Cranford," she picked up and saved for a possible emergency.

One of Aunt Sarah's special economies was the saving of twine and paper bags. The latter were always neatly folded, when emptied, and placed in a cretonne bag made for that purpose, hanging in a convenient corner of the kitchen.

Aunt Sarah's gingham apron was replaced afternoons by one made from fine, Lonsdale cambric, of ample proportions, and on special occasions she donned a hemstitched linen apron, inset at upper edge of hem with crocheted lace insertion, the work of her own deft fingers. Aunt Sarah's aprons, cut straight, on generous lines, were a part of her individuality.

Sarah Landis declared: "Happiness consists in giving and in serving others," and she lived up to the principles she advocated. She frequently quoted from the "Sons of Martha," by Kipling:

"I think this so fine," said Aunt Sarah, "and so true a sentiment that I am almost compelled to forgive Kipling for saying 'The female of the species is more deadly than the male.'"

Aunt Sarah's goodness was reflected in her face and in the tones of her voice, which were soft and low, yet very decided. She possessed a clear, sweet tone, unlike the slow, peculiar drawl often aiding with the rising inflection peculiar to many country folk among the "Pennsylvania Germans."

The secret of Aunt Sarah's charm lay in her goodness. Being always surrounded by a cheery atmosphere, she benefited all with whom she came in contact. She took delight in simple pleasures. She had the power of extracting happiness from the common, little every-day tasks and frequently remarked, "Don't strive to live without work, but to find more joy in your work." Her opinions were highly respected by every one in the neighborhood, and, being possessed of an unselfish disposition, she thought and saw good in every one; brought out the best in one, and made one long to do better, just to gain her approval, if for no higher reward. Sarah Landis was a loyal friend and one would think the following, by Mrs. Craik, applied to her:

"Oh, the comfort, the inexpressible comfort, of feeling safe with a person—having neither to weigh thoughts nor measure words, but pouring them all right out, just as they are—chaff and grain together, certain that a faithful hand will take and sift them, keep what is worth keeping and then with the breath of kindness blow the rest away."

She was never so happy as when doing an act of kindness for some poor unfortunate, and often said. "If 'twere not for God and good people, what would become of the unfortunate?" and thought like George McDonald, "If I can put one touch of rosy sunset into the life of any man or woman (I should add child) I shall feel that I have worked with God."

Aunt Sarah's sweet, lovable face was the first beheld by many a little, new-born infant; her voice, the first to hush its wailing cries as she cuddled it up to her motherly breast, and oft, with loving hands, softly closed the lids over eyes no longer able to see; whom the Gracious Master had taken into His keeping.

One day I overheard Aunt Sarah quote to a sorrowing friend these fine, true lines from Longfellow's "Resignation": "Let us be patient, these severe afflictions not from the ground arise, but celestial benedictions assume the dark disguise."

The day preceding that of Mary's arrival at the farm was a busy one for Aunt Sarah, who, since early morning, had been preparing the dishes she knew Mary enjoyed. Pans of the whitest, flakiest rolls, a large loaf of sweetest nut-brown, freshly-baked "graham bread," of which Mary was especially fond; an array of crumb-cakes and pies of every description covered the well-scrubbed table in the summer kitchen, situated a short distance from the house. A large, yellow earthenware bowl on the table contained a roll of rich, creamy "smier kase" just as it had been turned from the muslin bag, from which the "whey" had dripped over night; ready to be mixed with cream for the supper table. Pats of sweet, freshly-churned butter, buried in clover blossoms, were cooling in the old spring-house near by.

The farm house was guiltless of dust from cellar to attic. Aunt Sarah was a model housekeeper; she accomplished wonders, yet never appeared tired or flurried as less systematic housekeepers often do, who, with greater expenditure of energy, often accomplish less work. She took no unnecessary steps; made each one count, yet never appeared in haste to finish her work.

Said Aunt Sarah, "The lack of system in housework is what makes it drudgery. If young housekeepers would sit down and plan their work, then do it, they would save time and labor. When using the fire in the range for ironing or other purposes, use the oven for preparing dishes of food which require long, slow cooking, like baked beans, for instance. Bake a cake or a pudding, or a pan of quickly-made corn pone to serve with baked beans, for a hearty meal on a cold winter day. A dish of rice pudding placed in the oven requires very little attention, and when baked may be placed on ice until served. If this rule be followed, the young housewife will be surprised to find how much easier will be the task of preparing a meal later in the day, especially in hot weather."

The day following, John Landis drove to the railroad station, several miles distant, to meet his niece. As Mary stepped from the train into the outstretched arms of her waiting Uncle, many admiring glances followed the fair, young girl. Her tan-gold naturally wavy, masses of hair rivaled ripened grain. The sheen of it resembled corn silk before it has been browned and crinkled by the sun. Her eyes matched in color the exquisite, violet-blue blossoms of the chicory weed. She possessed a rather large mouth, with upturned corners, which seemed made for smiles, and when once you had been charmed with them, she had made an easy conquest of you forever. There was a sweet, winning personality about Mary which was as impossible to describe as to resist. One wondered how so much adorable sweetness could be embodied in one small maid. But Mary's sweetness of expression and charming manner covered a strong will and tenacity of purpose one would scarcely have believed possible, did they not have an intimate knowledge of the young girl's disposition. Her laugh, infectious, full of the joy of living, the vitality of youth and perfect health and happiness, reminded one of the lines: "A laugh is just like music for making living sweet."

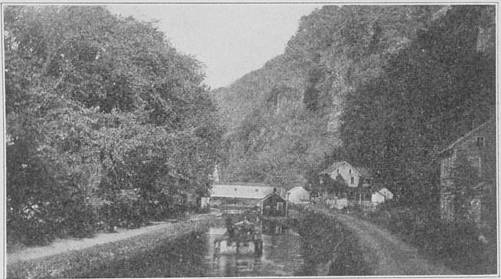

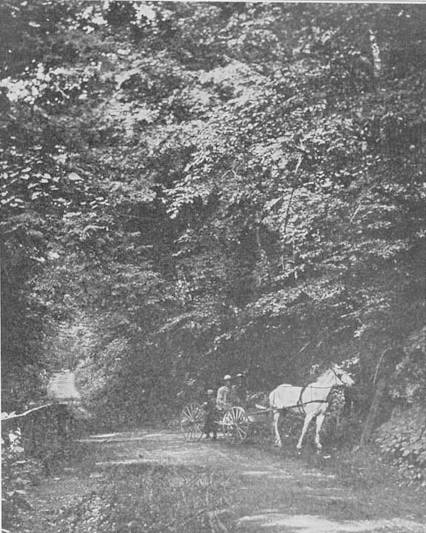

Seated beside her Uncle in the carriage, Mary was borne swiftly through the town out into the country. It was one of those preternaturally quiet, sultry days when the whole universe appears lifeless and inert, free from loud noise, or sound of any description, days which we occasionally have in early Spring or Summer, when the stillness is oppressive.

Frequently at such times there is borne to the nostrils the faint, stifling scent of burning brush, indicating that land is being cleared by the forehanded, thrifty farmer for early planting. Often at such times, before a shower, may be distinctly heard the faintest twitter and "peep, peep" of young sparrows, the harsh "caw, caw" of the crow, and the song of the bobolink, poised on the swaying branch of a tall tree, the happiest bird of Spring; the dozy, drowsy hum of bees; the answering call of lusty young chanticleers, and the satisfied cackle of laying hens and motherly old biddies, surrounded by broods of downy, greedy little newly-hatched chicks. The shrill whistle of a distant locomotive startles one with its clear, resonant intonation, which on a less quiet day would pass unnoticed. Mary, with the zest of youth, enjoyed to the full the change from the past months of confinement in a city school, and missed nothing of the beauty of the country and the smell of the good brown earth, as her Uncle drove swiftly homeward.

"Uncle John," said Mary, "'tis easy to believe God made the country."

"Yes," rejoined her Uncle, "the country is good enough for me."

"With the exception of the one day in the month, when you attend the 'Shriners' meeting' in the city," mischievously supplemented Mary, who knew her Uncle's liking for the Masonic Lodge of which he was a member, "and," she continued, "I brought you a picture for your birthday, which we shall celebrate tomorrow. The picture will please you, I know. It is entitled, 'I Love to Love a Mason, 'Cause a Mason Never Tells.'"

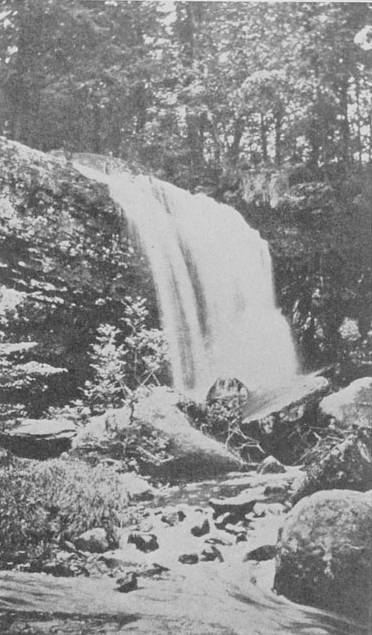

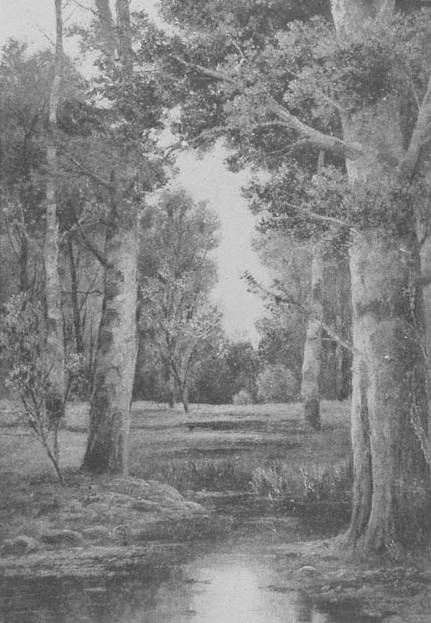

They passed cultivated farms. Inside many of the rail fences, inclosing fields of grain or clover, were planted numberless sour cherry trees, snowy with bloom, the ground underneath white with fallen petals. The air was sweet with the perfume of the half-opened buds on the apple trees in the near-by orchards and rose-like pink blossoms of the "flowering" crab-apple, in the door yards. Swiftly they drove through cool, green, leafy woods, crossing a wooden bridge spanning a small stream, so shallow that the stones at the bottom were plainly to be seen. A loud splash, as the sound of carriage wheels broke the uninterrupted silence, and a commotion in the water gave evidence of the sudden disappearance of several green-backed frogs, sunning themselves on a large, moss-grown rock, projecting above the water's edge; from shady nooks and crevices peeped clusters of early white violets; graceful maidenhair ferns, and hardier members of the fern family, called "Brake," uncurled their graceful, sturdy fronds from the carpet of green moss and lichen at the base of tree trunks, growing along the water's edge. Partly hidden by rocks along the bank of the stream, nestled a few belated cup-shaped anemones or "Wind Flowers," from which most of the petals had blown, they being one of the earliest messengers of Spring. Through the undergrowth in the woods, in passing, could be seen the small buds of the azalea or wild honeysuckle, "Sheep's Laurel," the deep pink buds on the American Judas tree, trailing vines of "Tea Berry," and beneath dead leaves one caught an occasional glimpse of fragrant, pink arbutus. In marshy places beside the creek, swaying in the wind from slender stems, grew straw-colored, bell-shaped blossoms of "Adder's Tongue" or "Dog Tooth Violet," with their mottled green, spike-shaped leaves. In the shadow of a large rock grew dwarf huckleberry bushes, wild strawberry vines, and among grasses of many varieties grew patches of white and pink-tinted Alsatian clover.

Leaving behind the spicy, fragrant, "woodsy" smell of wintergreen, birch and sassafras, and the faint, sweet scent of the creamy, wax-like blossoms of "Mandrake" or May apple, peeping from beneath large, umbrella-like, green leaves they emerged at last from the dim, cool shadows of the woods into the warm, bright sunlight again.

Almost before Mary realized it, the farm house could be seen in the distance, and her Uncle called her attention to his new, red barn, which had been built since her last visit to the farm, and which, in her Uncle's estimation, was of much greater importance than the house.

Mary greeted with pleasure the old landmarks so familiar to her on former visits. They passed the small, stone school house at the crossroads, and in a short time the horses turned obediently into the lane leading to the barn a country lane in very truth, a tangle of blackberry vines, wild rose bushes, by farmers called "Pasture Roses," interwoven with bushes of sumach, wild carrots and golden rod.

Mary insisted that her Uncle drive directly to the barn, as was his usual custom, while she was warmly welcomed at the farm house gate by her Aunt. As her Uncle led away the horses, he said, "I will soon join you, Mary, 'to break of our bread and eat of our salt,' as they say in the 'Shrine.'"

On their way to the house, Mary remarked: "I am so glad we reached here before dusk. The country is simply beautiful! Have you ever noticed, Aunt Sarah, what a symphony in green is the yard? Look at the buds on the maples and lilacs—a faint yellow green—and the blue-green pine tree near by; the leaves of the German iris are another shade; the grass, dotted with yellow dandelions, and blue violets; the straight, grim, reddish-brown stalks of the peonies before the leaves have unfolded, all roofed over with the blossom-covered branches of pear, apple and 'German Prune' trees. Truly, this must resemble Paradise!"

"Yes," assented her Aunt, "I never knew blossoms to remain on the pear trees so long a time. We have had no 'blossom shower' as yet to scatter them, but there will be showers tonight, I think, or I am no prophet. I feel rain in the atmosphere, and Sibylla said a few moments ago she heard a 'rain bird' in the mulberry tree."

"Aunt Sarah," inquired Mary, "is the rhubarb large enough to use?"

"Yes, indeed, we have baked rhubarb pies and have had a surfeit of dandelion salad or 'Salat,' as our neighbors designate it. Your Uncle calls 'dandelion greens' the farmers' spring tonic; that and 'celadine,' that plant you see growing by the side of the house. Later in the season it bears small, yellow flowers not unlike a very small buttercup blossom, and it is said to be an excellent remedy for chills and fevers, and it tastes almost as bitter as quinine. There are bushels of dandelion blossoms, some of which we shall pick tomorrow, and from them make dandelion wine."

"And what use will my thrifty Aunt make of the blue violets?" mischievously inquired Mary.

"The violets," replied her Aunt, "I shall dig up carefully with some earth adhering to their roots and place them in a glass bowl for a centrepiece on the table for my artistic and beauty-loving niece; and if kept moist, you will be surprised at the length of time they will remain 'a thing of beauty' if not 'a joy forever.' And later, Mary, from them I'll teach you to make violet beads."

"Aunt Sarah, notice that large robin endeavoring to pull a worm from the ground. Do you suppose the same birds return here from the South every Summer?"

"Certainly, I do."

"That old mulberry tree, from the berries of which you made such delicious pies and marmalade last Summer, is it dead?"

"No; only late about getting its Spring outfit of leaves."

"Schuggenhaus," said Sarah Landis, speaking to her niece, Mary Midleton, "is one of the largest and most populous townships in Bucks County, probably so named by the early German settlers, some of whom, I think, were my father's ancestors, as they came originally from Zweibrucken, Germany, and settled in Schuggenhaus Township. Schuggenhaus is one of the most fertile townships in Bucks County and one of the best cultivated; farming is our principal occupation, and the population of the township today is composed principally of the descendants of well-to-do Germans, frequently called 'Pennsylvania Dutch.'"

"I have often heard them called by that name," said Mary. "Have you forgotten, Aunt Sarah, you promised to tell me something interesting about the first red clover introduced in Bucks County?"

"Red clover," replied her Aunt, "that having bright, crimson-pink heads, is the most plentiful and the most common variety of clover; but knowing how abundantly it grows in different parts of the country at the present time, one would scarcely have believed, in olden times, that it would ever be so widely distributed as it now is.

"One reason clover does so well in this country is that the fertilization of the clover is produced by pollenation by the busy little bumble-bee, who carries the pollen from blossom to blossom, and clover is dependent upon these small insects for fertilization, as without them clover would soon die out."

"I admire the feathery, fuzzy, pink-tipped, rabbit-foot clover," said Mary; "it is quite fragrant, and usually covered with butterflies. It makes such very pretty bouquets when you gather huge bunches of it."

"No, Mary, I think you are thinking of Alsatian clover, which is similar to white clover. The small, round heads are cream color, tinged with pink; it is very fragrant and sweet and grows along the roadside and, like the common white clover, is a favorite with bees. The yellow hop clover we also find along the roadside. As the heads of clover mature, they turn yellowish brown and resemble dried hops; sometimes yellow, brown and tan blossoms are seen on one branch. The cultivation of red clover was introduced here a century ago, and when in bloom the fields attracted great attention. Being the first ever grown in this part of Bucks County, people came for miles to look at it, the fence around the fields some days being lined with spectators, I have been told by my grandfather. I remember when a child nothing appeared to me more beautiful than my father's fields of flax; a mass of bright blue flowers. I also remember the fields of broom-corn. Just think! We made our own brooms, wove linen from the flax raised on our farm and made our own tallow candles. Mary, from what a thrifty and hard-working lot of ancestors you are descended! You inherit from your mother your love of work and from your father your love of books. Your father's uncle was a noted Shakespearean scholar."

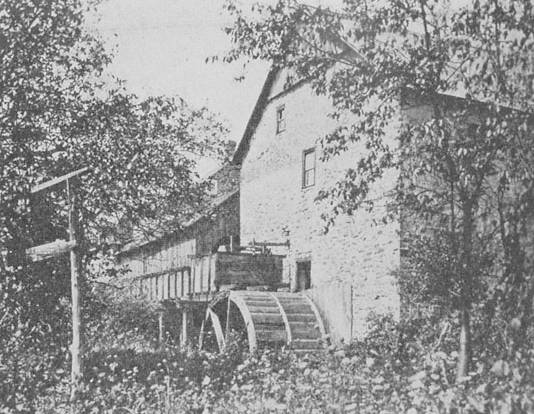

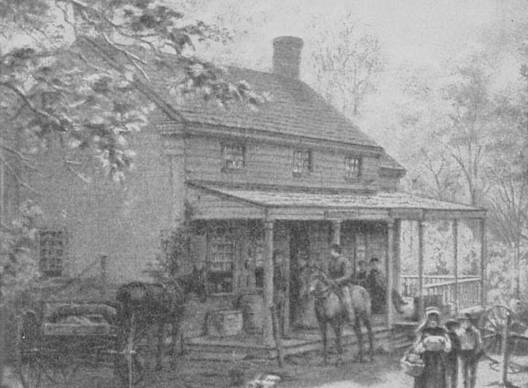

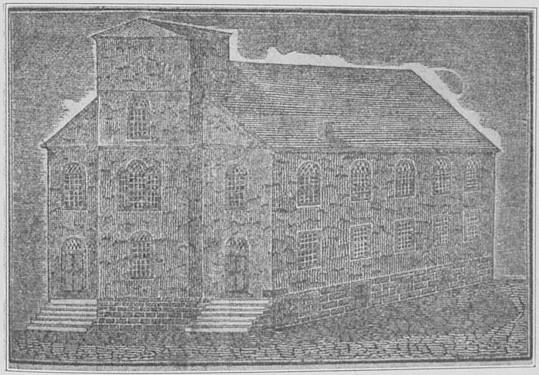

Many old-time industries are passing away. Yet Sarah Landis, was a housewife of the old school and still cooked apple butter, or "Lodt Varrik," as the Germans call it; made sauerkraut and hard soap, and naked old-fashioned "German" rye bread on the hearth, which owed its excellence not only to the fact of its being hearth baked but to the rye flour being ground in an old mill in a near-by town, prepared by the old process of grinding between mill-stones instead of the more modern roller process. This picture of the old mill, taken by Fritz Schmidt, shows it is not artistic, but, like most articles of German manufacture, the mill was built more for its usefulness than to please the eye.

"Aunt Sarah, what is pumpernickel?" inquired Mary, "is it like rye bread?"

"No, my dear, not exactly, it is a dark-colored bread, used in some parts of Germany. Professor Schmidt tells me the bread is usually composed of a mixture of barley flour and rye flour. Some I have eaten looks very much like our own brown bread. Pumpernickel is considered a very wholesome bread by the Germans—and I presume one might learn to relish it, but I should prefer good, sweet, home-made rye bread. I was told by an old gentleman who came to this country from Germany when a boy, that pumpernickel was used in the German army years ago, and was somewhat similar to 'hard tack,' furnished our soldiers in the Civil War. But I cannot vouch for the truth of this assertion."

"Aunt Sarah," said Mary later, "Frau Schmidt tells me the Professor sends his rye to the mill and requests that every part of it be ground without separating—making what he calls 'whole rye flour,' and from this Frau Schmidt bakes wholesome, nutritious bread which they call 'pumpernickel,' She tells me she uses about one-third of this 'whole rye flour' to two-thirds white bread flour when baking bread, and she considers bread made from this whole grain more wholesome and nutritious than the bread made from our fine rye flour."

The Bucks County farmer, John Landis, rather more scholarly in appearance than men ordinarily found in agricultural districts, was possessed of an adust complexion, caused by constant exposure to wind and weather; tall and spare, without an ounce of superfluous fat; energetic, and possessed of remarkable powers of endurance. He had a kindly, benevolent expression; his otherwise plain face was redeemed by fine, expressive brown eyes. Usually silent and preoccupied, and almost taciturn, yet he possessed a fund of dry humor. An old-fashioned Democrat, his wife was a Republican. He usually accompanied Aunt Sarah to her church, the Methodist, although he was a member of the German Reformed, and declared he had changed his religion to please her, but change his politics, never. A member of the Masonic Lodge, his only diversion was an occasional trip to the city with a party of the "boys" to attend a meeting of the "Shriners."

Aunt Sarah protested. "The idea, John, at your age, being out so late at night and returning from the city on the early milk train the following morning, and then being still several miles from home. It's scandalous!"

He only chuckled to himself; and what the entertainment had been, which was provided at Lulu Temple, and which he had so thoroughly enjoyed, was left to her imagination. His only remark when questioned was: "Sarah, you're not in it. You are not a 'Shriner.'" And as John had in every other particular fulfilled her ideal of what constitutes a good husband, Sarah, like the wise woman she was, allowed the subject to drop.

A good, practical, progressive farmer, John Landis constantly read, studied and pondered over the problem of how to produce the largest results at least cost of time and labor. His crops were skillfully planted in rich soil, carefully cultivated and usually harvested earlier than those of his neighbors. One summer he raised potatoes so large that many of them weighed one pound each, and new potatoes and green peas, fresh from the garden, invariably appeared on Aunt Sarah's table the first of July, and sometimes earlier. I have known him to raise cornstalks which reached a height of thirteen feet, which were almost equaled by his wife's sunflower stalks, which usually averaged nine feet in height.

Aunt Sarah, speaking one day to Mary, said: "Your Uncle John is an unusually silent man. I have heard him remark that when people talk continuously they are either very intelligent or tell untruths." He, happening to overhear her remark, quickly retorted:

When annoyed at his wife's talkativeness, her one fault in her husband's eyes, if he thought she had a fault, he had a way of saying, "Alright, Sarah, Alright," as much as to say "that is final; you have said enough," in his peculiar, quick manner of speaking, which Aunt Sarah never resented, he being invariably kind and considerate in other respects.

John Landis was a successful farmer because he loved his work, and found joy in it. While not unmindful of the advantages possessed by the educated farmer of the present day, he said, "'Tis not college lore our boys need so much as practical education to develop their efficiency. While much that we eat and wear comes out of the ground, we should have more farmers, the only way to lower the present high cost of living, which is such a perplexing problem to the housewife. There is almost no limit to what might be accomplished by some of our bright boys should they make agriculture a study. Luther Burbank says, 'To add but one kernel of corn to each ear grown in this country in a single year would increase the supply five million bushels.'"

The old unpainted farm house, built of logs a century ago, had changed in the passing years to a grayish tint. An addition had been built to the house several years before Aunt Sarah's occupancy, The sober hue of the house harmonized with the great, gnarled old trunk of the meadow willow near-by. Planted when the house was built, it spread its great branches protectingly over it. A wild clematis growing at the foot of the tree twined its tendrils around the massive trunk until in late summer they had become an inseparable part of it, almost covering it with feathery blossoms.

Near by stood an antique arbor, covered with thickly-clustering vines, in season bending with the weight of "wild-scented" grapes, their fragrance mingling with the odor of "Creek Mint" growing near by a small streamlet and filling the air with a delicious fragrance. The mint had been used in earlier years by Aunt Sarah's grandfather as a beverage which he preferred to any other.

From a vine clambering up the grape arbor trellies, in the fall of the year, hung numerous orange-colored balsam apples, which opened, when ripe, disclosing bright crimson interior and seeds. These apples, Aunt Sarah claimed, if placed in alcohol and applied externally, possessed great medicinal value as a specific for rheumatism.

A short distance from the house stood the newly-built red barn, facing the pasture lot. On every side stretched fields which, in summer, waved with wheat, oats, rye and buckwheat, and the corn crib stood close by, ready for the harvest to fill it to overflowing. Beside the farm house door stood a tall, white oleander, planted in a large, green-painted wooden tub. Near by, in a glazed earthenware pot, grew the old-fashioned lantana plant, covered with clusters of tiny blossoms, of various shades of orange, red and pink.

In flower beds outlined by clam shells which had been freshly whitewashed blossomed fuchsias, bleeding hearts, verbenas, dusty millers, sweet clove-scented pinks, old-fashioned, dignified, purple digitalis or foxglove, stately pink Princess Feather, various brilliant-hued zinnias, or more commonly called "Youth and Old Age," and as gayly colored, if more humble and lowly, portulacas; the fragrant white, star-like blossoms of the nicotiana, or "Flowering Tobacco," which, like the yellow primrose, are particularly fragrant at sunset. Geraniums of every hue, silver-leaved and rose-scented; yellow marigolds and those with brown, velvety petals; near by the pale green and white-mottled leaves of the plant called "Snow on the Mountain" and in the centre of one of the large, round flower beds, grew sturdy "Castor Oil Beans," their large, copper-bronze leaves almost covering the tiny blue forget-me-nots growing beneath. Near the flower bed grew a thrifty bush of pink-flowering almonds; not far distant grew a spreading "shrub" bush, covered with fragrant brown buds, and beside it a small tree of pearly-white snowdrops.

Sarah Landis loved the wholesome, earthy odors of growing plants and delighted in her flowers, particularly the perennials, which were planted promiscuously all over the yard. I have frequently heard her quote: "One is nearer God's heart in a garden than any place else on earth." And she would say, "I love the out-of-door life, in touch with the earth; the natural life of man or woman." Inside the fence of the kitchen garden were planted straight rows of both red and yellow currants, and several gooseberry bushes. In one corner of the garden, near the summer kitchen, stood a large bush of black currants, from the yellow, sweet-scented blossoms of which Aunt Sarah's bees, those "Heaven instructed mathematicians," sucked honey. Think of Aunt Sarah's buckwheat cakes, eaten with honey made from currant, clover, buckwheat and dandelion blossoms!

Her garden was second to none in Bucks County. She planted tomato seeds in boxes and placed them in a sunny window, raising her plants early; hence she had ripe tomatoes before any one else in the neighborhood. Her peas were earlier also, and her beets and potatoes were the largest; her corn the sweetest; and, as her asparagus bed was always well salted, her asparagus was the finest to be had.

Through the centre of the garden patch, on either side the walk, were large flower beds, a blaze of brilliant color from early Spring, when the daffodils blossomed, until frost killed the dahlias, asters, scarlet sage, sweet Williams, Canterbury bells, pink and white snapdragon, spikes of perennial, fragrant, white heliotrope; blue larkspur, four o'clocks, bachelor buttons and many other dear, old-fashioned flowers. The dainty pink, funnel-shaped blossoms of the hardy swamp "Rose Mallow'" bloomed the entire Summer, the last flowers to be touched by frost, vying in beauty with the pink monthly roses planted near by.

Children who visited Aunt Sarah delighted in the small Jerusalem cherry tree, usually covered with bright, scarlet berries, which was planted near the veranda, and they never tired pinching the tiny leaves of the sensitive plant to see them quickly droop, as if dead, then slowly unfold and straighten as if a thing of life.

Visitors to the farm greatly admired the large, creamy-white lily-like blossoms of the datura. Farthest from the house were the useful herb beds, filled with parsley, hoarhound, sweet marjoram, lavender, saffron, sage, sweet basil, summer savory and silver-striped rosemary or "old man," as it was commonly called by country folk.

Tall clusters of phlox, a riot of color in midsummer, crimson-eyed, white and rose-colored blossoms topping the tall stems, and clusters of brilliant-red bergamot near by had been growing, from time immemorial, a cluster of green and white-striped grass, without which no door yard in this section of Bucks County was considered complete in olden times. Near by, silvery plumes of pampas grass gently swayed on their reed-like stems. Even the garden was not without splashes of color, where, between rows of vegetables, grew pale, pink-petaled poppies, seeming to have scarcely a foothold in the rich soil. But the daintiest, sweetest bed of all, and the one that Mary enjoyed most, was where the lilies of the valley grew in the shade near a large, white lilac bush. Here, on a rustic bench beneath an old apple tree, stitching on her embroidery, she dreamed happy dreams of her absent lover, and planned for the life they were to live together some day, in the home he was striving to earn for her by his own manly exertions; and she assiduously studied and pondered over Aunt Sarah's teaching and counsel, knowing them to be wise and good.

A short distance from the farm house, where the old orchard sloped down to the edge of the brook, grew tall meadow rue, with feathery clusters of green and white flowers; and the green, gold-lined, bowl-shaped blossoms of the "Cow Lily," homely stepsisters of the fragrant, white pond lily, surrounded by thick, waxy, green leaves, lazily floated on the surface of the water from long stems in the bed of the creek, and on the bank a carpet was formed by golden-yellow, creeping buttercups.

In the side yard grew two great clumps of iris, or, as it is more commonly called, "Blue Flag." Its blossoms, dainty as rare orchids, with lily-like, violet-veined petals of palest-tinted mauve and purple.

On the sunny side of the old farm house, facing the East, where at early morn the sun shone bright and warm, grew Aunt Sarah's pansies, with velvety, red-brown petals, golden-yellow and dark purple. They were truly "Heart's Ease," gathered with a lavish hand, and sent as gifts to friends who were ill. The more she picked the faster they multiplied, and came to many a sick bed "sweet messengers of Spring."

If Aunt Sarah had a preference for one particular flower, 'twas the rose, and they well repaid the time and care she lavished on them. She had pale-tinted blush roses, with hearts of deepest pink; rockland and prairie and hundred-leaf roses, pink and crimson ramblers, but the most highly-prized roses of her collection were an exquisite, deep salmon-colored "Marquis De Sinety" and an old-fashioned pink moss rose, which grew beside a large bush of mock-orange, the creamy blossoms of the latter almost as fragrant as real orange blossoms of the sunny Southland. Not far distant, planted in a small bed by themselves, grew old-fashioned, sweet-scented, double petunias, ragged, ripple, ruffled corollas of white, with splotches of brilliant crimson and purple, their slender stems scarcely strong enough to support the heavy blossoms.

In one of the sunniest spots in the old garden grew Aunt Sarah's latest acquisition. "The Butterfly Bush," probably so named on account of its graceful stems, covered with spikes of tiny, lilac-colored blossoms, over which continually hovered large, gorgeously-hued butterflies, vying with the flowers in brilliancy of color, from early June until late Summer.

Aunt Sarah's sunflowers, or "Sonnen Blume," as she liked to call them, planted along the garden fence to feed chickens and birds alike, were a sight worth seeing. The birds generally confiscated the larger portion of seeds. A pretty sight it was to see a flock of wild canaries, almost covering the tops of the largest sunflowers, busily engaged picking out the rich, oily seeds.

Aunt Sarah loved the golden flowers, which always appeared to be nodding to the sun, and her sunflowers were particularly fine, some being as much as fifty inches in circumference.

A bouquet of the smaller ones was usually to be seen in a quaint, old, blue-flowered, gray jar on the farm house veranda in Summertime. Earlier in the season blossoms of the humble artichoke, which greatly resemble small sunflowers, or large yellow daisies, filled the jar. Failing either of these, she gathered large bouquets of golden-rod or wild carrot blossoms, both of which grew in profusion along the country lanes and roadside near the farm. But the old gray jar never held a bouquet more beautiful than the one of bright, blue "fringed gentians," gathered by Aunt Sarah in the Fall of the year, several miles distant from the farm.

A short time after her arrival at the farm Mary poured into the sympathetic ear of Aunt Sarah her hopes and plans. Her lover, Ralph Jackson, to whom she had become engaged the past Winter, held a position with the Philadelphia Electric Company, and was studying hard outside working hours. His ambition was to become an electrical engineer. He was getting fair wages, and wished Mary to marry him at once. She confessed she loved Ralph too well to marry him, ignorant as she was of economical housekeeping and cooking.

Mary, early left an orphan, had studied diligently to fit herself for a kindergarten teacher, so she would be capable of earning her own living on leaving school, which accounted for her lack of knowledge of housework, cooking, etc.

Aunt Sarah, loving Mary devotedly, and knowing the young man of her choice to be clean, honest and worthy, promised to do all in her power to make their dream of happiness come true. Learning from Mary that Ralph was thin and pale from close confinement, hard work and study, and of his intention of taking a short vacation, she determined he should spend it on the farm, where she would be able to "mother him."

"You acted sensibly, Mary," said her Aunt, "in refusing to marry Ralph at the present time, realizing your lack of knowledge of housework and inability to manage a home. Neither would you know how to spend the money provided by him economically and wisely, and, in this age of individual efficiency, a business knowledge of housekeeping is almost as important in making a happy home as is love. I think it quite as necessary that a woman who marries should understand housekeeping in all its varied branches as that the man who marries should understand his trade or profession; for, without the knowledge of means to gain a livelihood (however great his love for a woman), how is the man to hold that woman's love and affection unless he is able by his own exertions to provide her with necessities, comforts, and, perhaps, in later years, luxuries? And in return, the wife should consider it her duty and pleasure to know how to do her work systematically; learn the value of different foods and apply the knowledge gained daily in preparing them; study to keep her husband in the best of health, physically and mentally. Then will his efficiency be greater and he will be enabled to do his 'splendid best' in whatever position in life he is placed, be he statesman or hod-carrier. What difference, if an honest heart beat beneath a laborer's hickory shirt, or one of fine linen? 'One hand, if it's true, is as good as another, no matter how brawny or rough.' Mary, do not think the trivial affairs of the home beneath your notice, and do not imagine any work degrading which tends to the betterment of the home. Remember, 'Who sweeps a room as for Thy law, makes that and the action fine.'

"Our lives are all made up of such small, commonplace things and this is such a commonplace old world, Mary. 'The commonplace earth and the commonplace sky make up the commonplace day,' and 'God must have loved common people, or He would not have made so many of them.' And, what if we are commonplace? We cannot all be artists, poets and sculptors. Yet, how frequently we see people in commonplace surroundings, possessing the soul of an artist, handicapped by physical disability or lack of means! We are all necessary in the great, eternal plan. 'Tis not good deeds alone for which we receive our reward, but for the performance of duty well done, in however humble circumstances our lot is cast. Is it not Lord Houghton who says: 'Do not grasp at the stars, but do life's plain, common work as it comes, certain that daily duties and daily bread are the sweetest things of life.' I consider a happy home in the true sense of the word one of the greatest of blessings. How important is the work of the housemother and homemaker who creates the home! There can be no happiness there unless the wheels of the domestic machinery are oiled by loving care and kindness to make them run smoothly, and the noblest work a woman can do is training and rearing her children. Suffrage, the right of woman to vote; will it not take women from the home? I am afraid the home will then suffer in consequence. Will man accord woman the same reverence she has received in the past? Should she have equal political rights? A race lacking respect for women would never advance socially or politically. I think women could not have a more important part in the government of the land than in rearing and educating their children to be good, useful citizens. In what nobler work could women engage than in work to promote the comfort and well-being of the ones they love in the home? I say, allow men to make the laws, as God and nature planned. I think women should keep to the sphere God made them for—the home. Said Gladstone, 'Woman is the most perfect when most womanly.' There is nothing, I think, more despicable than a masculine, mannish woman, unless it be an effeminate, sissy man. Dr. Clarke voiced my sentiments when he said: 'Man is not superior to woman, nor woman to man. The relation of the sexes is one of equality, not of better or worse, of higher and lower. The loftiest ideal of humanity demands that each shall be perfect in its kind and not be hindered in its best work. The lily is not inferior to the rose, nor the oak superior to the clover; yet the glory of the lily is one and the glory of the oak is another, and the use of the oak is not the use of the clover.'

"This present-day generation demands of women greater efficiency in the home than ever before. And Mary, many of the old-time industries which I had been accustomed to as a girl have passed away. Electricity and numerous labor-saving devices make household tasks easier, eliminating some altogether. When housekeeping you will find time to devote to many important questions of the day which we old-time housekeepers never dreamed of having. Considerable thought should be given to studying to improve and simplify conditions of the home-life. It is your duty. Obtain books; study food values and provide those foods which nourish the body, instead of spending time uselessly preparing dainties to tempt a jaded appetite. Don't spoil Ralph when you marry him. Give him good, wholesome food, and plenty of it; but although the cooking of food takes up much of a housekeeper's time, it is not wise to allow it to take up one's time to the exclusion of everything else. Mary, perhaps my views are old-fashioned. I am not a 'new woman' in any sense of the word. The new woman may take her place beside man in the business world and prove equally as efficient, but I do not think woman should invade man's sphere any more than he should assume her duties."

"Aunt Sarah, I am surprised to hear you talk in that manner about woman's sphere," replied Mary, "knowing what a success you are in the home, and how beautifully you manage everything you undertake. I felt, once you recognized the injustice done woman in not allowing them to vote, you would feel differently, and since women are obliged to obey the laws, should they not have a voice in choosing the lawmakers? When you vote, it will not take you out of the home. You and Uncle John will merely stop on your way to the store, and instead of Uncle John going in to write and register what he thinks should be done and by whom it should be done, you too will express your opinion. This will likely be twice a year. By doing this, no woman loses her womanliness, goodness or social position, and to these influences the vote is but another influence. I know there are many things in connection with the right of equal suffrage with what you do not sympathize.

"Aunt Sarah, let me tell you about a dear friend of mine who taught school with me in the city. Emily taught a grammar grade, and did not get the same salary the men teachers received for doing the same work, which I think was unfair. Emily studied and frequently heard and read about what had been done in Colorado and other States where women vote. She got us all interested, and the more we learned about the cause the harder we worked for it. Emily married a nice, big, railroad man. They bought a pretty little house in a small town, had three lovely children and were very happy. More than ever as time passed Emily realized the need of woman's influence in the community. It is true, I'll admit, Aunt Sarah, housekeeping and especially home-making are the great duties of every woman, and to provide the most wholesome, nourishing food possible for the family is the duty of every mother, as the health, comfort and happiness of the family depend so largely on the common sense (only another name for efficiency) and skill of the homemaker, and the wise care and though she expends on the preparation of wholesome, nutritious food in the home, either the work of her own hands or prepared under her direction. You can not look after these duties without getting outside of your home, especially when you live like Emily, in a town where the conditions are so different from living as you do on a farm in the country. Milk, bread and water are no longer controlled by the woman in her home, living in cities and towns; and just because women want to look out for their families they should have a voice in the larger problems of municipal housekeeping. To return to Emily, she did not bake her own bread, as you do, neither did she keep a cow, but bought milk and bread to feed the children. Wasn't it her duty to leave the home and see where these products were produced, and if they were sanitary? And, knowing the problem outside the home would so materially affect the health, and perhaps lives, of her children, she felt it her distinctive duty to keep house in a larger sense. When the children became old enough to attend school, Emily again took up her old interest in schools. She began to realize how much more just it would be if an equal number of women were on the school board."

"But what did the husband think of all this?" inquired Aunt Sarah, dubiously.

"Oh, Tom studied the case, too, at first just to tease Emily, but he soon became as enthusiastic as Emily. He said, 'The first time you are privileged to vote, Emily, I will hire an automobile to take you to the polls in style.' But poor Emily was left alone with her children last winter. Tom died of typhoid fever. Contracted it from the bad drainage. They lived in a town not yet safeguarded with sewerage. Now Emily is a taxpayer as well as a mother, and she has no say as far as the town and schools are concerned. There are many cases like that, where widows and unmarried women own property, and they are in no way represented. And think of the thousands and thousands of women who have no home to stay in and no babies to look after."

"Mercy, Mary! Do stop to take breath. I never thought when I started this subject I would have an enthusiastic suffragist with whom to deal."

"I am glad you started the subject, Aunt Sarah, because there is so much to be said for the cause. I saw you glance at the clock and I see it is time to prepare supper. But some day I'm going to stop that old clock and bring down some of my books on 'Woman's Suffrage' and you'll he surprised to hear what they have done in States where equal privileges were theirs. I am sure 'twill not be many years before every State in the Union will give women the right of suffrage."

After Mary retired that evening Aunt Sarah had a talk with her John, whom she knew needed help on the farm. As a result of the conference, Mary wrote to Ralph the following day, asking him to spend his vacation on the farm as a "farm hand." Needless to say, the offer was gladly accepted by Ralph, if for no other reason than to be near the girl he loved.

Ralph came the following week—"a strapping big fellow," to quote Uncle John, being several inches over six feet.

"All you need, young chap," said Mary's Uncle, "is plenty of good, wholesome food of Sarah's and Mary's preparing, and I'll see that you get plenty of exercise in the fresh air to give you an appetite to enjoy it, and you'll get a healthy coat of tan on your pale cheeks before the Summer is ended."

Ralph Jackson, or "Jack," as he was usually called by his friends, an orphan like Mary, came of good, old Quaker stock, his mother having died immediately after giving birth to her son. His father, supposed to be a wealthy contractor, died when Ralph was seventeen, having lost his fortune through no fault of his own, leaving Ralph penniless.

Ralph Jackson possessed a good face, a square, determined jaw, sure sign of a strong will and quick temper; these Berserker traits he inherited from his father; rather unusual in a Quaker. He possessed a head of thick, coarse, straight brown hair, and big honest eyes. One never doubted his word, once it had been given. 'Twas good as his bond. This trait he inherited also from his father, noted for his truth and integrity. Ralph was generous to a fault. When a small boy he was known to take off his shoes and give them to a poor little Italian (who played a violin on the street for pennies) and go home barefoot.

Ralph loved Mary devotedly, not only because she fed him well at the farm, as were his forefathers, the "Cave Men," fed by their mates in years gone by, but he loved her first for her sweetness of disposition and lovable ways; later, for her quiet unselfishness and lack of temper over trifles—so different from himself.

When speaking to Mary of his other fine qualities, Aunt Sarah said: "Ralph is a manly young fellow; likeable, I'll admit, but his hasty temper is a grave fault in my eyes."

Mary replied, "Don't you think men are very queer, anyway, Aunt Sarah? I do, and none of us is perfect."

To Mary, Ralph's principal charm lay in his strong, forceful way of surmounting difficulties, she having a disposition so different. Mary had a sweet, motherly way, seldom met with in so young a girl, and this appealed to Ralph, he having never known "mother love," and although not at all inclined to be sentimental, he always called Mary his "Little Mother Girl" because of her motherly ways.

"Well," continued Mary's Aunt, "a quick temper is one of the most difficult faults to overcome that flesh is heir to, but Ralph, being a young man of uncommon good sense, may in time curb his temper and learn to control it, knowing that unless be does so it will handicap him in his career. Still, a young girl will overlook many faults in the man she loves. Mary, ere marrying, one should be sure that no love be lacking to those entering these sacred bonds. 'Tis not for a day, but for a lifetime, to the right thinking. Marriage, as a rule, is too lightly entered into in this Twentieth Century of easy divorces, and but few regard matrimony in its true holy relation, ordained by our Creator. If it be founded on the tower of enduring love and not ephemeral passion, it is unassailable, lasting in faith and honor until death breaks the sacred union and annuls the vows pledged at God's holy altar."

"Well," replied Mary, as her Aunt paused to take breath, "I am sure of my love for Ralph."

"God grant you may both be happy," responded her Aunt.

"Mary, did you ever hear this Persian proverb? You will understand why I have so much to say after hearing it."

Speaking to Mary of life on the farm one day, Ralph laughingly said: "I am taught something new every day. Yesterday your Uncle told me it was 'time to plant corn when oak leaves were large as squirrels' ears.'" Ralph worked like a Trojan. In a short time both his hands and face took on a butternut hue. He became strong and robust. Mary called him her "Cave Man," and it taxed the combined efforts of Aunt Sarah and Mary to provide food to satisfy the ravenous appetite Mary's "Cave Man" developed. And often, after a busy day, tired but happy, Mary fell asleep at night to the whispering of the leaves of the Carolina poplar outside her bedroom window.

But country life on a farm has its diversions. One of Mary's and Ralph's greatest pleasures after a busy day at the farm was a drive about the surrounding country early Summer evenings, frequently accompanied by either Elizabeth or Pauline Schmidt, their nearest neighbors.

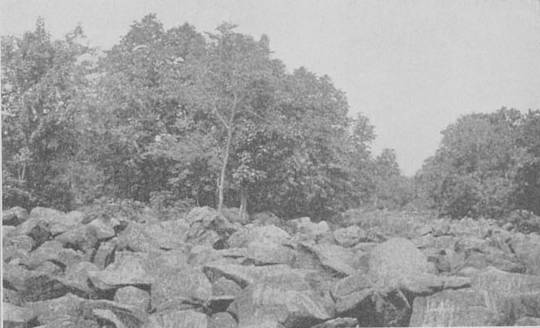

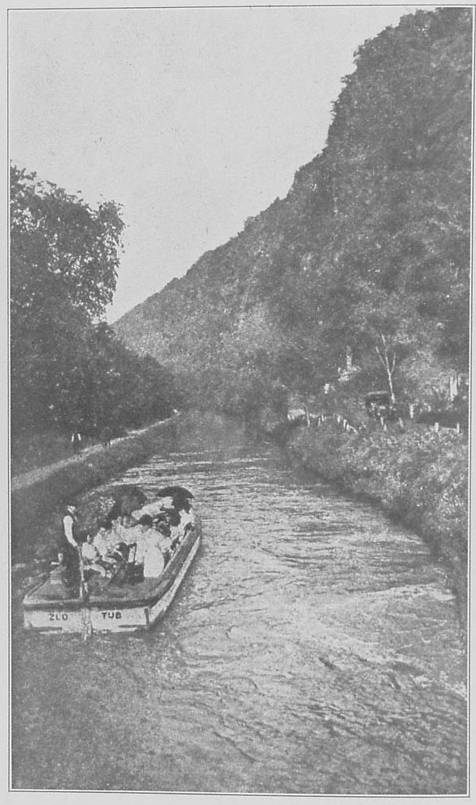

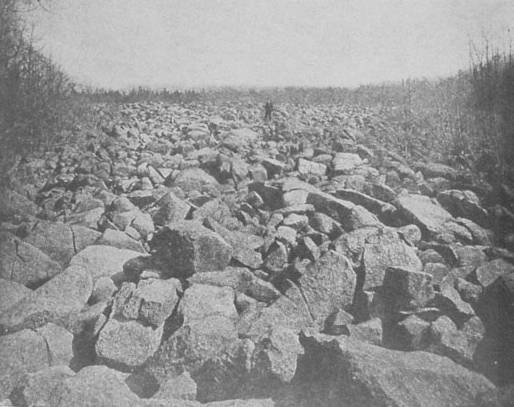

One of the first places visited by them was a freak of nature called "Rocky Valley," situated at no great distance from the farm.

A small country place named "Five Oaks," a short distance from "Clear Spring" farm, was owned by a very worthy and highly-educated, but rather eccentric, German professor. He came originally from Heidelberg, but had occupied the position of Professor of German for many years in a noted university in a near by town. A kind, warm-hearted, old-fashioned gentleman was the Professor; a perfect Lord Chesterfield in manners. Very tall, thin almost to emaciation, although possessed of excellent health; refined, scholarly looking: a rather long, hooked nose, faded, pale-blue eyes; snowy, flowing "Lord Dundreary" whiskers, usually parted in the centre and twisted to a point on either side with the exceedingly long, bony fingers of his well-kept, aristocratic-looking white hands. He had an abrupt, quick, nervous manner when speaking. A fringe of thin, white hair showed at the lower edge of the black silk skull cap which he invariably wore about home, and in the absence of this covering for his bald head, he would not have looked natural to his friends.

The Professor always wore a suit of well-brushed, "shiny" black broadcloth, and for comfort old-fashioned soft kid "gaiters," with elastic in the sides. He was a man with whom one did not easily become acquainted, having very decided opinions on most subjects. He possessed exquisite taste, a passionate love of music, flowers and all things beautiful; rather visionary, poetical and a dreamer; he was not practical, like his wife; warm-hearted, impulsive, energetic Frau Schmidt, who was noted for her executive abilities. I can imagine the old Professor saying as Mohammed has been quoted as saying, "Had I two loaves, I would sell one and buy hyacinths to feed my soul." Impulsive, generous to a fault, quick to take offense, withal warm-hearted, kind and loyal to his friends, he was beloved by the students, who declared that "Old Snitzy" always played fair when he was obliged to reprimand them for their numerous pranks, which ended sometimes, I am obliged to confess, with disastrous results. The dignified old Professor would have raised his mild, blue, spectacled eyes in astonishment had he been so unfortunate as to have overheard the boys, to whom he was greatly attached, call their dignified preceptor by such a nickname.

The Professor's little black-eyed German wife, many years younger than her husband, had been, before her marriage, teacher of domestic science in a female college in a large city. "She was a most excellent housekeeper," to quote the Professor, and "a good wife and mother."

The family consisted of "Fritz," a boy of sixteen, with big, innocent, baby-blue eyes like his father, who idolized his only son, who was alike a joy and a torment. Fritz attended the university in a near-by town, and was usually head of the football team. He was always at the front in any mischief whatever, was noted for getting into scrapes innumerable through his love of fun, yet he possessed such a good-natured, unselfish, happy-go-lucky disposition that one always forgave him.

Black-eyed, red-cheeked Elizabeth was quick and impulsive, like her mother. A very warm and lasting friendship sprung up between merry Elizabeth and serious Mary Midleton during Mary's Summer on the farm, although not at all alike in either looks or disposition, and Elizabeth was Mary's junior by several years.

The third, last and least of the Professor's children was Pauline, or "Pollykins," as she was always called by her brother Fritz, the seven-year-old pet and baby of the family. A second edition of Fritz, the same innocent, questioning, violet-blue eyes, fair complexion, a kissable little mouth and yellow, kinky hair, she won her way into every one's heart and became greatly attached to Mary, who was usually more patient with the little maid (who, I must confess, was sometimes very willful) than was her sister Elizabeth. Mary, who had never been blessed with a sister, dearly loved children, and thought small "Polly" adorable, and never wearied telling her marvelous fairy tales.

Shortly after Mary's advent at the farm she one day said: "Aunt Sarah, the contents of this old trunk are absolutely worthless to me; perhaps they may be used by you for carpet rags."

"Mary Midleton!" exclaimed Aunt Sarah, in horrified tones, "you extravagant girl. I see greater possibilities in that trunk of partly-worn clothing than, I suppose, a less economically-inclined woman than I ever would have dreamed of."

Mary handed her Aunt two blue seersucker dresses, one plain, the other striped. "They have both shrunken, and are entirely too small for me," said Mary.

"Well," said her Aunt, considering, "they might be combined in one dress, but you need aprons for kitchen work more useful than those little frilly, embroidered affairs you are wearing. We should make them into serviceable aprons to protect your dresses. Mary, neatness is an attribute that every self-respecting housewife should assiduously cultivate, and no one can be neat in a kitchen without a suitable apron to protect one from grime, flour and dust."

"What a pretty challis dress; its cream-colored ground sprinkled over with pink rose buds!"

Mary sighed. "I always did love that dress, Aunt Sarah, 'Twas so becoming, and he—he—admired it so!"

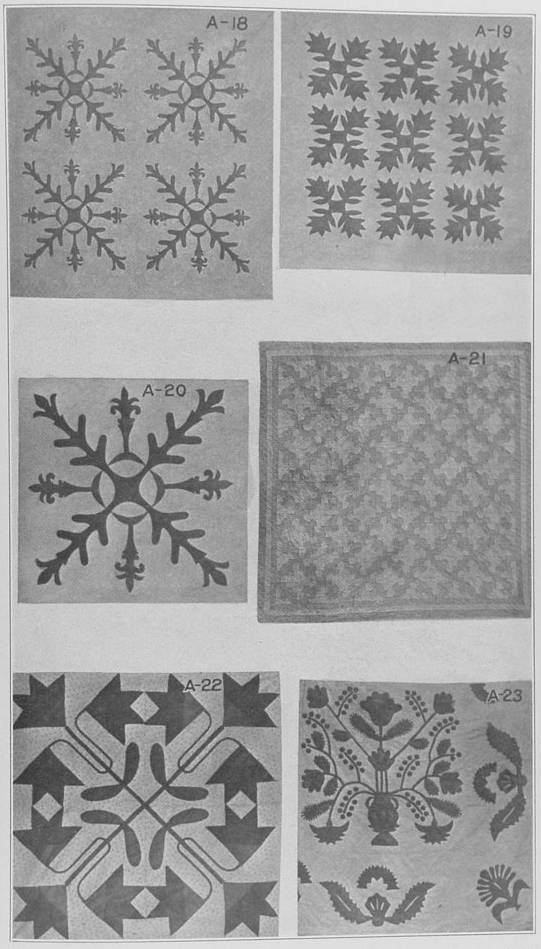

"And HE, can do so still," replied Aunt Sarah, with a merry twinkle in her kind, clear, gray eyes, "for that pale-green suesine skirt, slightly faded, will make an excellent lining, with cotton for an interlining, and pale green Germantown yarn with which to tie the comfortable. At small cost you'll have a dainty, warm spread which will be extremely pretty in the home you are planning with HIM. I have several very pretty-old-style patchwork quilts in a box in the attic which I shall give you when you start housekeeping. That pretty dotted, ungored Swiss skirt will make dainty, ruffled sash curtains for bedroom windows. Mary, sometimes small beginnings make great endings; if you make the best of your small belongings, some day your homely surroundings will be metamorphosed into what, in your present circumstances, would seem like extravagant luxuries. An economical young couple, beginning life with a homely, home-made rag carpet, have achieved in middle age, by their own energy and industry, carpets of tapestry and rich velvet, and costly furniture in keeping; but, never—never, dear, are they so valued, I assure you, as those inexpensive articles, conceived by our inventive brain and manufactured by our own deft fingers during our happy Springtime of life when, with our young lover husband, we built our home nest on the foundation of pure, unselfish, self-sacrificing love."

Aunt Sarah sighed; memory led her far back to when she had planned her home with her lover, John Landis, still her lover, though both have grown gray together, and shared alike the joys and sorrows of the passing years. Aunt Sarah had always been the perfect "housemother" or "Haus Frau," as the Germans phrase it, and on every line of her matured face could be read an anxious care for the family welfare. Truly could it be said of her, in the language of Henry Ward Beecher: "Whoever makes home seem to the young dearer and happier is a public benefactor."

Aunt Sarah said earnestly to Mary, "I wish it were possible for me to impart to young, inexperienced girls, about to become housewives and housemothers, a knowledge of those small economics, so necessary to health and prosperity, taught me by many years of hard work, mental travail, experience and some failures. In this extravagant Twentieth Century economy is more imperative than formerly. We feel that we need so much more these days than our grandmothers needed; and what we need, or feel that we need, is so costly. The housemother has larger problems today than yesterday.

"Every husband should give his wife an allowance according to his income, so that she will be able to systematize her buying and occasionally obtain imperishable goods at less cost. Being encouraged thus to use her dormant economical powers; she will become a powerful factor in the problem of home-making along lines that will essentially aid her husband in acquiring a comfortable competency, if not a fortune. Then she will have her husband's interest truly at heart; will study to spend his money carefully, and to the best advantage; and she herself, even, will be surprised at the many economies which will suggest themselves to save his hard-earned money when she handles that money herself, which certainly teaches her the saving habit and the value of money.

"The majority of housewives of today aren't naturally inclined to be extravagant or careless. It is rather that they lack the knowledge and experience of spending money, and spending it to the best advantage for themselves and their household needs.

"'Tis a compulsory law in England, I have heard, to allow a wife pin money, according to a man's means. 'Tis a most wise law. To a loyal wife and mother it gives added force, dignity and usefulness to have a sufficient allowance and to be allowed unquestioningly to spend that money to her best ability. Her husband, be he a working or professional man, would find it greatly to his advantage in the home as well as in his business and less of a drain on his bank account should he give his wife a suitable allowance and trust her to spend it according to her own intelligence and thrift.

"Child, many a man is violently prejudiced against giving a young wife money; many allow her to run up bills, to her hurt and to his, rather than have her, even in her household expenditure, independent of his supervision. I sincerely hope, dear, that your intended, Ralph Jackson, will be superior to this male idiosyncrasy, to term it mildly, and allow you a stated sum monthly. The home is the woman's kingdom, and she should be allowed to think for it, to buy for it, and not to be cramped by lack of money to do as she thinks best for it."

"But, Aunt Sarah, some housewives are so silly that husbands cannot really be blamed for withholding money from them and preventing them from frittering it away in useless extravagance."

"Mary, wise wives should not suffer for those who are silly and extravagant. I don't like to be sarcastic, but with the majority of the men, silliness appeals to them more than common sense. Men like to feel their superiority to us. However, though inexperienced, Mary, you aren't silly or extravagant, and Ralph could safely trust you with his money. It makes a woman so self-respecting, puts her on her mettle, to have money to do as she pleases with, to be trusted, relied upon as a reasoning, responsible being. A man, especially a young husband, makes a grave mistake when he looks upon his wife as only a toy to amuse him in his leisure moments and not as one to be trusted to aid him in his life work. A trusted young housewife, with a reasonable and regular allowance at her command, be she ever so inexperienced, will soon plan to have wholesome, nutritious food at little cost, instead of not knowing until a half hour before meal time what she will serve. She would save money and the family would be better nourished; nevertheless, I would impress it on the young housewife not to be too saving or practice too close economy, especially when buying milk and eggs, as there is nothing more nutritious or valuable. A palatable macaroni and cheese; eggs or a combination of eggs and milk, are dishes which may be substituted occasionally, at less expense, for meat. A pound of macaroni and cheese equals a pound of steak in food value. Take time and trouble to see that all food be well cooked and served, both in an attractive and appetizing manner. Buy the cheaper cuts of stewing meats, and by long, slow simmering, they will become sweet and tender and of equal nutritive value as higher priced sirloins and tenderloins.

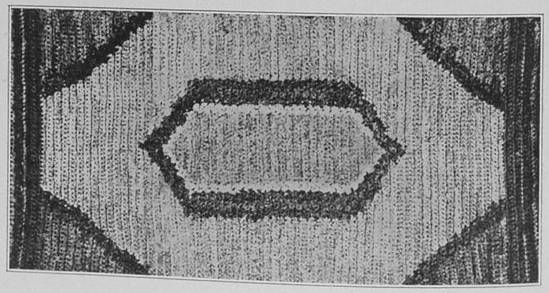

"But, Mary, I've not yet finished that trunk and its contents. That slightly-faded pink chambray I'll cut up into quilt blocks. Made up with white patches, and quilted nicely, a pretty quilt lined with white, will be evolved. I have such a pretty design of pink and white called the 'Winding Way,' very simple to make. The beauty of the quilt consists altogether in the manner in which the blocks are put together, or it might be made over the pattern called 'The Flying Dutchman.' From that tan linen skirt may be made a laundry bag, shoe pocket, twine bag, a collar bag and a table runner, the only expense being several skeins of green embroidery silk, and a couple yards of green cord to draw the bags up with, and a couple of the same-hued skirt braids for binding edges, and," teasingly, "Mary, you might embroider Ralph Jackson's initials on the collar and laundry bag."

Mary blushed rosily red and exclaimed in an embarrassed manner, most bewitchingly, "Oh!"

Aunt Sarah laughed. She thought to have Mary look that way 'twas worth teasing her.

"Well, Mary, we can in leisure moments, from that coarse, white linen skirt which you have discarded, make bureau scarfs, sideboard cover, or a set of scalloped table mats to place under hot dishes on your dining-room table. I will give you pieces of asbestos to slip between the linen mats when finished. They are a great protection to the table. You could also make several small guest towels with deep, hemstitched ends with your initials on. You embroider so beautifully, and the drawn work you do is done as expertly as that of the Mexican women."

"Oh, Aunt Sarah, how ingenious you are."

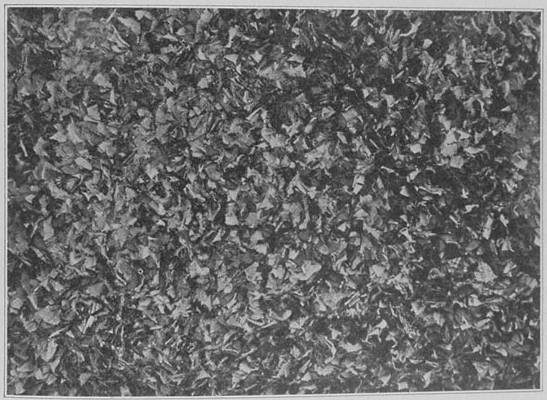

"And, Mary, your rag carpet shall not be lacking. We shall tear up those partly-worn muslin skirts into strips one-half inch in width, and use the dyes left over from dyeing Easter eggs. I always save the dye for this purpose, they come in such pretty, bright colors. The rags, when sewed together with some I have in the attic, we'll have woven into a useful carpet for the home you are planning.'

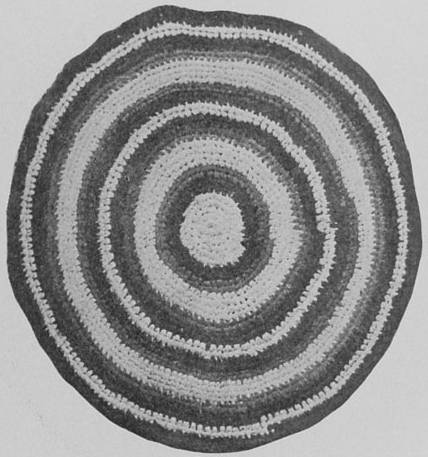

"Oh! Aunt Sarah," exclaimed Mary, "do you mean a carpet like the one in the spare bedroom?"

"Yes, my dear, exactly like that, if you wish."

"Indeed I do, and I think one like that quite good enough to have in a dining-room. I think it so pretty. It does not look at all like a common rag carpet."

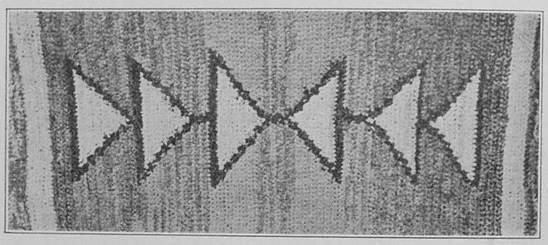

"No, my dear, it is nothing very uncommon. It is all in the way it is woven. Instead of having two gay rainbow stripes about three inches wide running through the length of the carpet, I had it woven with the ground work white and brown chain to form checks. Then about an inch apart were placed two threads of two shades of red woolen warp, alternating with two threads of two shades of green, across the whole width, running the length of the carpet. It has been greatly admired, as it is rather different from that usually woven. All the rag carpets I found in the house when we moved here, made by John's mother, possessed very wide stripes of rainbow colors, composed of shaded reds, yellows, blues and greens. You can imagine how very gorgeous they were, and so very heavy. Many of the country weavers use linen chain or warp instead of cotton, and always use wool warp for the stripes."

"Aunt Sarah, I want something so very much for the Colonial bedroom I should like to have when I have a home of my very own."

"What is it, dear? Anything, e'en to the half of my kingdom," laughingly replied her Aunt.

"Why, I'd love to have several rag rugs like those in your bedroom, which you call 'New Colonial' rugs."

"Certainly, my dear. They are easily made from carpet rags. I have already planned in my mind a pretty rag rug for you, to be made from your old, garnet merino shirtwaist, combined with your discarded cravenette stormcoat.

"And you'll need some pretty quilts, also," said her Aunt.

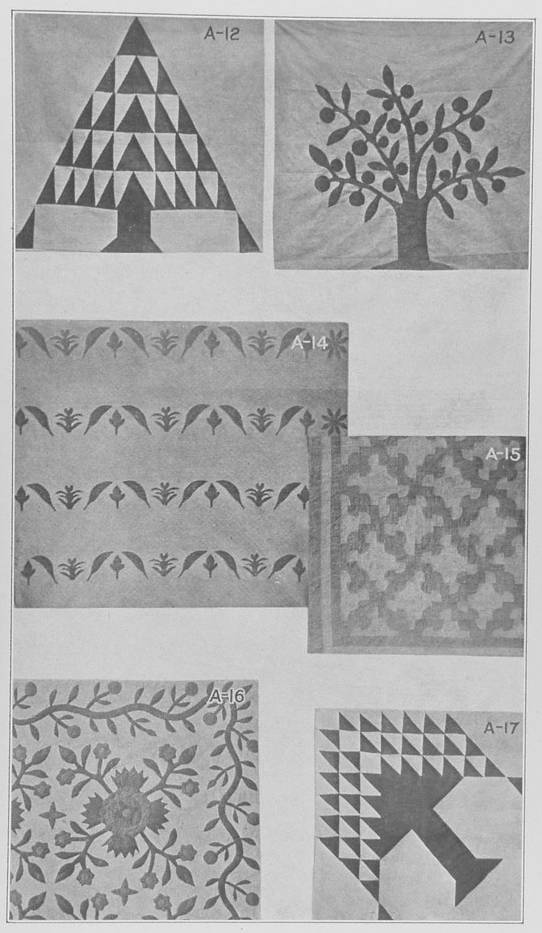

"I particularly admire the tree quilts," said Mary.

"You may have any one you choose; the one called 'Tree of Paradise,' another called 'Pineapple Design,' which was originally a border to 'Fleur de lis' quilt or 'Pine Tree,' and still another called 'Tree of Life,' and 'The Lost Rose in the Wilderness.'"

"They are all so odd," said Mary, "I scarcely know which one I think prettiest."

"All are old-fashioned quilts, which I prize highly," continued her Aunt. "Several I pieced together when a small girl, I think old-time patchwork too pretty and useful an accomplishment to have gone out of fashion.

"You shall have a small stand cover like the one you admired so greatly, given me by Aunt Cornelia. It is very simple, the materials required being a square of yard-wide unbleached muslin. In the centre of this baste a large, blue-flowered handkerchief with cream-colored ground, to match the muslin. Turn up a deep hem all around outside edge; cut out quarter circles of the handkerchief at each of four corners; baste neatly upon the muslin, leaving a space of muslin the same width as the hem around each quarter circle; briarstitch all turned-in edges with dark-blue embroidery silk, being washable, these do nicely as covers for small tables or stands on the veranda in Summertime."

"Aunt Sarah," ecstatically exclaimed Mary, "you are a wizard to plan so many useful things from a trunk of apparently useless rags. What a treasure Uncle has in you. I was fretting about having so little to make my home attractive, but I feel quite elated at the thought of having a carpet and rugs already planned, besides the numerous other things evolved from your fertile brain."

Aunt Sarah loved a joke. She held up an old broadcloth cape. "Here is a fine patch for Ralph Jackson's breeches, should he ever become sedentary and need one."

Mary reddened and looked almost offended and was at a loss for a reply.

Greatly amused, Aunt Sarah quoted ex-President Roosevelt: "'Tis time for the man with the patch to come forward and the man with the dollar to step back,'" and added, "Never mind, Mary, your Ralph is such an industrious, hustling young man that he will never need a patch to step forward, I prophesy that with such a helpmeet and 'Haus Frau' as you, Mary, he'll always be most prosperous and happy. Kiss me, dear."

Mary did so, and her radiant smile at such praise from her honored relative was beautiful to behold.

"Aunt Sarah," questioned Mary one day, "do you mind if I copy some of your recipes?"

"Certainly not, my dear," replied her Aunt.

"And I'd like to copy some of the poems, also, I never saw any one else have so much poetry in a book of cooking recipes."

"Perhaps not," replied her Aunt, "but you know, Mary, I believe in combining pleasure with my work, and our lives are made up of poetry and prose, and some lives are so very prosy. Many times when too tired to look up a favorite volume of poems, it has rested me to turn the pages of my recipe book and find some helpful thought, and a good housewife will always keep her book of recipes where it may be readily found for reference. I think, Mary, the poem 'Pennsylvania,' by Lydia M.D. O'Neil, a fine one, and I never tire of reading it over and over again. I have always felt grateful to my old schoolmaster. Professor T——, for teaching me, when a school girl, to love the writing of Longfellow, Whittier, Bryant, Tennyson and other well-known poets. I still, in memory, hear him repeat 'Thanatopsis,' by Bryant and 'The Builders,' by Longfellow. The rhymes of the 'Fireside Poet' are easily understood, and never fail to touch the heart of common folk. I know it appears odd to see so many of my favorite poems sandwiched in between old, valued cooking recipes, but, Mary, the happiness of the home life depends so largely on the food we consume. On the preparation and selection of the food we eat depends our health, and on our health is largely dependent our happiness and prosperity. Who is it has said, 'The discovery of a new dish makes more for the happiness of man than the discovery of a star'? So, dearie, you see there is not such a great difference between the one who writes a poem and the one who makes a pie. I think cooking should be considered one of the fine arts—and the woman who prepares a dainty, appetizing dish of food, which appeals to the sense of taste, should be considered as worthy of praise as the artist who paints a fine picture to gratify our sense of sight. I try to mix all the poetry possible in prosaic every-day life. We country farmers' wives, not having the opportunities of our more fortunate city sisters, such as witnessing plays from Shakespeare, listening to symphony concerts, etc., turn to 'The Friendship of Books,' of which Washington Irving writes: 'Cheer us with the true friendship, which never deceived hope nor deserted sorrow.'"

"Yes," said Mary, "but remember, Aunt Sarah, Chautauqua will be held next Summer in a near-by town, and, as Uncle John is one of the guarantors, you will wish to attend regularly and will, I know, enjoy hearing the excellent lectures, music and concerts."

"Yea," replied her Aunt, "Chautauqua meetings will commence the latter part of June, and I will expect you and Ralph to visit us then. I think Chautauqua a godsend to country women, especially farmers' wives; it takes them away from their monotonous daily toil and gives them new thoughts and ideas."

"I can readily understand, Aunt Sarah, why the poem, 'Life's Common Things,' appeals to you; it is because you see beauty in everything. Aunt Sarah, where did you get this very old poem, 'The Deserted City'?"

"Why, that was given me by John's Uncle, who thought the poem fine."

"Indeed, it is a 'gem,'" said Mary, after slowly reading aloud parts of several stanzas.

"Yes," replied her Aunt, "Professor Schmidt tells me the poem was written by Kalidasa (the Shakespeare of Hindu literature), and was written 1800 years before Goldsmith gave us his immortal work, 'The Deserted Village.'"

"I like the poem, 'Abou Ben Adhem and the Angel,'" said Mary, "and I think this true by Henry Ward Beecher:"

"This is a favorite little poem of mine, Aunt Sarah. I'll just write it on this blank page in your book."

"Aunt Sarah, I see there is still space on this page to write another poem, a favorite of mine. It is called, 'Be Strong,' by Maltbie Davenport."

LIFE'S COMMON THINGS.

ABOU BEN ADHEM AND THE ANGEL.