FOREWORD: In this strange story of another day, the author has "dipped into the future" and viewed with his mind's eye the ultimate effect of America's self-satisfied complacency, and her persistent refusal to heed the lessons of Oriental progress. I can safely promise the reader who takes up this unique recital of the twentieth century warfare, that his interest will be sustained to the very end by the interesting deductions and the keen insight into the possibilities of the present trend of international affairs exhibited by the author.—Bernarr Macfadden.

"Kindly be prepared to absent yourself at a moment's notice." It was Goyu speaking, blundering, old fool. He was standing in the doorway with his kitchen-apron on, and an iron spoon in his hand.

"What on earth is the matter?" asked Ethel Calvert, tossing aside her French novel in alarm, for such a lack of deference in Goyu meant vastly more than appeared upon the surface.

"I am informed," replied Goyu, gravely, "that there has been an anti-foreign riot and that many are killed."

"And father?" gasped Ethel.

"He was upon the grain boat," said Goyu.

"But where is he now?"

"I do not know," returned Goyu, locking nervously over his shoulder. "But I fear he has not fared well—the boat was dynamited—that's what started the trouble."

With a gasp Ethel recalled that an hour before she had heard an explosion which she had supposed to be blasting. Faint with fear, she staggered toward a couch and fell forward upon the cushions.

When the girl regained consciousness the house was dark. Slowly she recalled the event that had culminated the uneventful day. She wondered if Goyu had been lying or had gone crazy. The darkness was not reassuring—her father always came home before dark, and his absence now confirmed her fears. She wondered if the old servant had deserted her. He was a poor stick anyway; Japanese men who had pride or character no longer worked as domestics in the households of foreigners.

Ethel Calvert was the daughter of an American grain merchant who represented the interests of the North American Grain Exporters Association at the seaport of Otaru, in Hokaidi, the North Island of Japan. Three years before her mother had died of homesickness and a broken heart—although the Japanese physician had called it tuberculosis, and had prescribed life in a tent! Had they not suffered discomforts enough in that barbarous country without adding insult to injury?

Ethel was bountifully possessed of the qualities of hothouse beauty. Her jet black hair hung over the snowy skin of her temples in striking contrast. Her form was of a delicate slenderness and her movement easy and graceful with just a little of that languid listlessness considered as a mark of well-bred femininity. She knew that she was beautiful according to the standards of her own people and her isolation from the swirl of the world's social life was to her gall and wormwood.

The Calverts had never really "settled" in Japan, but had merely remained there as homesick Americans indifferent to, or unjustly prejudiced against the Japanese life about them. Now, in the year 1958, the growing anti-foreign feeling among the Japanese had added to their isolation. Moreover, the Japanese bore the grain merchant an especial dislike, for every patriotic Japanese was sore at heart over the fact that, after a century of modern progress, Japan was still forced to depend upon foreigners to supplement their food supply.

In fact, they had oft heard Professor Oshima grieve over the statistics of grain importation, as a speculator might mourn his personal losses in the stock market.

For a time Ethel lay still and listened to the faint sound of voices from a neighboring porch. Then the growing horror of the situation came over her with anewed force; if her father was dead, she was not only alone in the world, but stranded in a foreign and an unfriendly country; for there were but few Americans left in the city.

The girl arose and crept nervously into the dining-room. She turned on the electric light; everything seemed in order. She hurried over to Goyu's room, and knocked. There was no answer. Then slowly opening the door, she peered in—the room was empty and disordered. Plainly the occupant had bundled together his few belongings and flown.

Ethel stole back through the silent house and tremblingly took down the telephone receiver. In vain she called the numbers of the few American families of the city. Last on the list was the American Consulate, and this time she received the curt information that the consul had left the city by aeroplane "with the other foreigners." The phrase struck terror into her heart. If the European population had flown in such haste as to overlook her, clearly there was danger. A great fear grew upon her. Afraid to remain where she was, she tried to think of ways of escape. She could not steer an aeroplane even if she were able to obtain one. Otaru was far from the common ways of international traffic and the ships lying at anchor in the harbor were freighters, Japanese owned and Japanese manned.

Ethel looked at her watch—it was nine-twenty. She tiptoed to her room.

An hour later she was in the street dressed in a tailored suit of American make and carrying in her hand-bag a few trinkets and valuables she had found in the house. Passing hurriedly through quiet avenues, she was soon in the open country. The road she followed was familiar to her, as she had traveled it many times by auto.

For hours she walked rapidly on. Her unpracticed muscles grew tired and her feet jammed forward in high-heeled shoes were blistered and sore. But fear lent courage and as the first rays of the morning sun peeked over the hill-tops, the refugee reached the outskirts of the city of Sapporo.

Ethel made straightway for the residence of Professor Oshima, the Soil Chemist of the Imperial Agricultural College of Hokiado—a Japanese gentleman who had been educated and who had married abroad, and a close friend of her father's. As she reached the door of the Professor's bungalow, she pushed the bell, and sank exhausted upon the stoop.

Some time afterward she half-dreamed and half realized that she found herself neatly tucked between white silk sheets and lying on a floor mattress of a Japanese sleeping-porch. A gentle breeze fanned her face through the lattice work and low slanting sunbeams sifting in between the shutters fell in rounded blotches upon the opposite straw matting wall. For a time she lay musing and again fell asleep.

When she next awakened, the room was dimly lighted by a little glowing electric bulb and Madame Oshima was sitting near her. Her hostess greeted her cordially and offered her water and some fresh fruit.

Madame Oshima was fully posted upon the riots and confirmed Ethel's fears as to the fate of her father.

"You will be safe here for the present," her hostess assured her. "Professor Oshima has been called to Tokio; when he returns we will see what can be done concerning your embarking for America."

Madame Oshima was of French descent but had fully adopted Japanese customs and ways of thinking.

As soon as Ethel was up and about, her hostess suggested that she exchange her American-made clothing for the Japanese costume of the time. But Ethel was inclined to rebel.

"Why," she protested, "if I discarded my corsets I would lose my figure."

"But have I lost my figure?" inquired the lithe Madame Oshima, striking an attitude.

To this Ethel did not reply, but continued, "And I would look like a man," for among the Japanese people tight-belted waists and flopping skirts had long since been replaced by the kimo, a single-piece garment worn by both sexes and which fitted the entire body with comfortable snugness.

"And is a man so ill-looking?" asked her companion, smiling.

"Why, no, of course not, only he's different. Why, I couldn't wear a kimo—people would see—my limbs," stammered the properly-bred American girl.

"Why, no, they couldn't," replied Madame Oshima. "Not if you keep your kimo on."

"But they would see my figure."

"Well, I thought you just said that was what you were afraid they wouldn't see."

"But I don't mean that way—they—they could see the shape of my—my legs," said Ethel, blushing crimson.

"Are you ashamed that your body has such vulgar parts?" returned the older woman.

"No, of course not," said Ethel, choking back her embarrassment. "But it's wicked for a girl to let men know such things."

"Oh, they all know it," replied Madame Oshima, "they learn it in school."

At this the highly strung Ethel burst into sobs.

"There, there now," said her companion, regretting that she had spoken sarcastically. "I forget that I once had such ideas also. We'll talk some more about it after while. You are nervous and worried now and must have more rest."

The next day Madame Oshima more tactfully approached the subject and showed her protege that while in Rome it was more modest to do as the Romans do; and that, moreover, it was necessary for her own good and theirs that she attract as little attention as possible, and to those that recognized her Caucasian blood appear, superficially, at least, as a naturalized citizen of Japan.

So, amid blushes and tears, protestations and laughter, Ethel accepted the kimo, or one-piece Japanese garment, and the outer flowing cloak to be worn on state occasions when freedom of bodily movement was not required. Her feather-adorned hat was discarded altogether and her ill-shapen high-heeled boots replaced by airy slippers of braided fiber.

Her rather short stature and her hair—which fortunately enough was black—served to lessen her conspicuousness, especially when dressed in the fashion followed by Japanese girls; and with the leaving off of the use of cosmetics and the spending of several hours a day in the flower garden even her pallid complexion suffered rapid change.

It was about a fortnight before Professor Oshima returned from Tokio. Upon his arrival Ethel at once pleaded with him to be sent to America, but the scientist slowly shook his head.

"It is too late," he said; "there is going to be a war."

Thus it happened that Ethel Calvert was retained in the Professor's family as a sort of English tutor to his children, and introduced as a relative of his wife, and no one suspected that she was one of the hated Americans.

The trouble between Japan and the United States dated back to the early part of the century. It was deep-seated and bitter, and was not only the culmination of a rivalry between the leading nations of the great races of mankind, but a rivalry between two great ideas or policies that grew out in opposite directions from the age of unprecedented mechanical and scientific progress that marked the dawn of the twentieth century.

The pages of history had been turned rapidly in those years. The United States, long known as the richest country, had also become the most populous nation of the Caucasian world—and wealth and population had made her vain.

But with all her material glory, there was not strength in American sinews, nor endurance in her lungs, nor vigor in the product of her loins. Her people were herded together in great cities, where they slept in gigantic apartment houses, like mud swallows in a sand bank. They overate of artificial food that was made in great factories. They over-dressed with tight-fitting unsanitary clothing made by the sweated labor of the diseased and destitute. They over-drank of old liquors born of ancient ignorance and of new concoctions born of prostituted science. They smoked and perfumed and doped with chemicals and cosmetics—the supposed virtues of which were blazoned forth on earth and sky day and night.

The wealth of the United States was enormous, yet it was chiefly in the hands of the few. The laborers went forth from their rookeries by subway and monorail, and served their shifts in the mills of industry.

In turn, others took their places, and the mills ground night and day.

Even the farm lands had been largely taken over by corporate control. Crops on the plains were planted with power machinery. The rough lands had all been converted into forests or game preserves for the rich. Agriculture had been developed as a science, but not as a husbandry. The forcing system had been generally applied to plants and animals. Wonder-working nitrogenous fertilizers made at Niagara and by the wave motors of the coast made all vegetation to grow with artificial luxury. Corn-fed hogs and the rotund carcasses of stall-fed cattle were produced on mammoth ranches for the edification of mankind, and fowl were hatched by the billions in huge incubators, and the chicks reared and slaughtered with scarcely a touch of a human hand. And all this was under the control of concentrated business organization. The old, sturdy, wasteful farmer class had gone out of existence.

Only the rich who owned aeroplanes could afford to live in the country. The poor had been forced to the cities where they could be sheltered en masse, and fed, as it were, by machinery. New York had a population of twenty-three millions. Manhattan Island had been extended by filling in the shallows of the bay, until the Battery reached almost to Staten Island. The aeroplane stations that topped her skyscrapers stood, many of them, a quarter of a mile from the ground.

As the materially greatest nation in the world, the United States had an enormous national patriotism based on vanity. The larger patriotism for humanity was only known in the prattle of her preachers and idealists. America was the land of liberty—and liberty had come to mean the right to disregard the rights of others.

In Japan, too, there had been changes, but Japan had received the gifts of science in a far different spirit. With her, science had been made to serve the more ultimate needs of the race, rather than the insane demand for luxuries.

The Japanese had applied to the human species the scientific principles of heredity, nutrition and physical development, which in America had been confined to plants and animals. The old spirit of Japanese patriotism had grown into a semi-religious worship of racial fitness and a moral pride developed which eulogized the sacrifice of the liberties of the individual to the larger needs of the people. Legal restrictions of the follies of fashion in dress and food, the prohibition of alcohol and narcotics, the restriction of unwise marriages, and the punishments of immorality were stoically accepted, not as the blue laws of religious fanaticism, but as requisites of racial progress and a mark of patriotism.

And while Japan showed no signs of the extravagant wealth seen in America, she was far from being poor. She had gained little from centralized and artificial industry, but she had wasted less in insane competition and riotous luxury.

But in Japanese life there was one unsolved problem. That was her food supply. Intensive culture would do wonders and the just administration of wealth and the physical efficiency of her people had eliminated the waste of supporting the non-productive, but an acre is but a small piece of land at most, and Japan had long since passed the point where the number of her people exceeded the number of her acres. A quarter of an acre would produce enough grain and coarse vegetables to keep a man alive, but the Japanese wanted eggs and fruit and milk for their children; and they wanted cherry trees and chrysanthemums, lotus ponds and shady gardens with little waterfalls.

Now if the low birth rate that had resulted when the examinations for parenthood were first enforced had continued, Japan would not have been so crowded, but after the first generation of marriage restriction the percentage of those who reached the legal standard of fitness was naturally increased. The scientists and officials had from time to time considered the advisability of increasing the restrictions—and yet why should they? The Japanese people had submitted to the prohibition of the marriage of the unfit, but they loved children; and, with their virile outdoor life, the instinct of procreation was strong within them. True, the assignable lands in Japan continued to grow smaller, but what reason was there for stifling the reproductive instincts of a vigorous people in a great unused world half populated by a degenerate humanity?

So Japan was land hungry—not for lands to conquer, as of old, nor yet for lands to exploit commercially, but for food and soil and breathing space for her children.

Among opponents of Japanese racial expansion, the United States was the greatest offender. Japanese immigration had long since been forbidden by the United States, and American diplomats had more recently been instrumental in bringing about an agreement among the powers of Europe by which all outlets were locked against the overflowing stream of Asiatic population.

Indeed, America called Japan the yellow peril; and with her own prejudices to maintain, her institutions of graft and exploitation to fatten her luxury-loving lords and her laborers to appease, she was in mortal terror of the simple efficiency of the Japanese people who had taken the laws of Nature into their own hands and shaped human evolution by human reason.

As Commodore Perry had forced the open door of commerce upon Japan a century before, so Japan decided to force upon America the acknowledgment of any human being's right to live in any land on earth. She had tried first by peaceful means to secure these ends, but failing here and driven on by the lash of her own necessity, Japan had come to feel that force alone could break the clannish resistance of the Anglo-Saxon, who having gone into the four corners of the earth and forced upon the world his language, commerce and customs, now refused to receive ideas or citizens in return.

And thus it came to pass that the West and the East were in the clutch of the War-God. No one knew just what the war would be like, for the wars of the last century had been bluffing, bulldozing affairs concerning trade agreements or Latin-American revolutions. There had been no great clash of great ideas and great peoples.

The harbors of the world were filled with huge, floating, flat-topped battleships, within the capacious interiors of which were packed the parts of aeroplanes as were the soldiers of the Grecian army in their wooden horse at Troy, for assembling and launching them. But the engines of warfare which men had repeatedly claimed would make war so terrible as to end war, had failed to fulfill anticipations. The means of defense and the rules of the game had kept pace with the means of destruction. The flat tops of the warships, which served as alighting platforms for friendly planes, were heavily armored against missiles dropped from unfriendly ones. The explosion of a bomb on top of a plate of steel is a rather tame affair, and guns sufficient to penetrate armor plate could not be carried on air-craft. The big guns of battleships, which had for a time grown bigger and bigger, had now gone quite out of use, for the coming of the armored top had been followed by the toad-stool warship, which had a roof like an inverted saucer, and was provided with water chambers, the opening of the traps of which caused a sudden sinking of the vessel until the eave dipped beneath the water level and left exposed only the sloping roof from which the heaviest shot would glance like a bullet from the frozen surface of a pond.

The first two years of war dragged on in the Pacific. American grain was of course cut off from Japan and the government authorities ordered the people to plow up their flower gardens and plant food crops.

The Americans had too much territory to protect to take the offensive and their Pacific fleet lay close to Manila, where, with the help of land aviation forces, they hoped to hold the possession of the islands, which according to the popular American view was supposed to be the prize for which the Japanese had gone to war.

The test of the actual warfare proved several things upon which mankind had long been in doubt. One of these was that, with all the expert mechanism that science and invention had supplied, the personal equation of the man could not be eliminated. Aviation increased the human element in warfare. To shoot straight requires calm nerves, but to fly straight requires also agility and endurance.

The American aeroplanes were made of steel and aluminum, and when they hit the water they sank like lead, but the Japanese planes were made of silk and bamboo, and their engines were built with multiple compartment air tanks and after a battle the Japanese picked up the floating engines and placed them, ready to use, in inexpensive new planes.

In the nineteenth month of the war, Manila surrendered, and the emblem of the rising sun was hoisted throughout the Philippine Islands. The remnant of the American fleet retreated across the Pacific, and the world supposed that the war was over.

But Japan refused the American proposals of peace, which conceded them the Philippines, unless the United States be also opened to universal immigration. And so it was that when Japan, in addition to accepting the Philippines, demanded the right to settle her cheap labor in the United States, the American authorities cut short the peace negotiation and began concentrating troops and battleships along the Pacific Coast in fear of an invasion of California.

With Ethel Calvert's adoption into Professor Oshima's family there came a great change in her life. At first, she accepted Japanese food and Japanese clothes as the old-time prisoner accepted stripes and bread and water. But her captivity proved less repulsive than she expected and she was soon confessing to herself that there was much good in Japanese life. Professor and Madame Oshima were not talkative on general topics but the books on the shelves of the Professor's library proved a godsend to the awakening mind of the young woman. Indeed, after a mental diet of French and English fiction upon which Ethel had been reared, the works on science and humaniculture, the dreams of universal brotherhood, the epics of a race in its conquests of disease and poverty were as meat and drink to her eager, hungry mind.

As the war went on, the horror of it all grew upon her. She read Howki's "America." She didn't believe it all, but she realized that most of it was true. She wondered why her people were fighting to keep out the Japanese. She marvelled that the Japanese who had adopted such lofty ideals of race culture could find the heart to go to war. She wished she might be free to go to the government officials at Tokio and Washington to show them the folly of it all. Surely if the American statesmen understood Japanese ideals and the superiority of their habits and customs for the production of happy human beings, they would never have waged war to keep them out of the States.

"In three days we leave Japan," said Professor Oshima, as he sat down to dinner one evening in the early part of April, 1960.

"All?" asked Komoru, the Professor's secretary.

"We four," replied Oshima, indicating those at the table, "the children will stay with my mother. I'll need your assistance, and as for Miss Ethel, she cannot well stay here, so I have had you two listed. Although it's a little irregular, I am sure it will not be questioned, for I know more about American soils than any other man in Japan."

Ethel glanced apprehensively at Komoru. She had never quite understood her own attitude toward that taciturn young Japanese whom she had seen daily for two years without hardly making his acquaintance. She admired him and yet she feared him.

Professor Oshima was saying that she had been "listed" with Komoru for some great journey. What did it mean? What could she do? Again she looked up at the secretary; but far from seeing any trace of scheme or plot in his enigmatical countenance, she found him to be considering the situation with the same equanimity with which he would have recorded the calcium content of a soil sample.

As for Professor and Madame Oshima, they seemed equally unruffled about the proposed journey, and not at all inclined to elucidate the mystery. Experience had taught the younger woman that when information was not offered it was unwise to ask questions, so when the Professor busied himself with much ransacking of his pamphlets and papers and his wife became equally occupied with overhauling the family wardrobe and getting the children off to their grandmother's, Ethel accepted unquestionably the statement that she would be limited to twenty kilograms of clothing and ten kilograms of other personal effects, and lent assistance as best she could to the enterprise in hand.

On the third day the little party, with their light luggage boarded a train for Hakodate, at which point they arrived at noon. Hurrying along the docks among others burdened like themselves, they came to a great low-lying, turtle-topped warship; and, passing down a gangway, entered the brilliantly lighted interior.

The constant flood of new passengers came, not in mixed and motley groups, as the ordinary crowd of passengers, but by two, male and female, as the unclean beasts into the ark. And they were all young in years and athletic in frame—the very cream and flower of the race.

Late that evening the vessel steamed out of port, and during the next two days was joined by a host of other war craft, and the great squadron moved in orderly procession to the eastward.

One point, that Ethel soon discovered was that, in addition to being excellent physical specimens, all the men, and many of the women, were proficient as aviators. Of these facts life on board bore ample evidence, for the great fan ventilated gymnasium was the most conspicuous part of the ship's equipment and here in regular drills and in free willed disportive exercise those on board kept themselves from stagnation during the idleness of the voyage. Into this gymnasium work Ethel entered with great gusto, for there was a revelation in the discovery of her own physical capabilities that surprised and fascinated her.

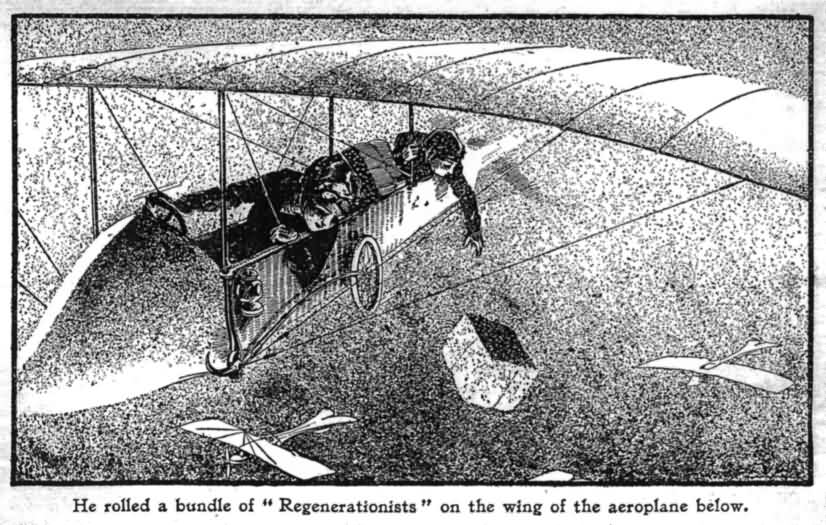

In the other chief interest of her fellow passengers, Ethel was an apt pupil, for though woefully ignorant of aviation, she was eager to learn. She spent many hours in the company of Professor or Madame Oshima, studying aeroplane construction and operation from the displayed mechanisms on board. In fact, they found the great roomy hold of the ship was packed with aeroplane parts. Small gasoline turbines were stored in crates by the hundreds; also wings and rudders knocked down and laid flat against each other and still lower down in the framework of the floating palace were vast stores of gasoline.

At the end of two weeks the Japanese squadron was in latitude 34° north, longitude 125° west, and headed directly for the Los Angeles district of Southern California—the richest and most densely populated area of the United States.

One evening, just at dark, after they had been in sight of the American aerial scouts all day, the Japanese fleet changed its course and turned sharply to the southward. Now Panama was six days' steaming from Los Angeles and less than three days from New Orleans. So the authorities at Washington ordered all warships and available soldiers on the Gulf Coast to embark for the Isthmus.

Meanwhile there was much going on beneath the armor plate of the Japanese transports, and on the fourth day of their southward movement the great trap doors were swung down and aeroplane parts were run out on the tramways, the planes rapidly set up by skilled workmen, and firmly hooked to the floor. Above and below deck they stood in great rows like lines of automobiles in a garage.

Towards sundown the forward planes were manned and in quick succession shot down the runways and took to the air. Ethel and her companions were below air the time and hardly knew what was going on. Their luggage had been taken up some time ago, except for an extra kima, which they had been ordered to put on. In their turn they were now called out and ordered to go above, that is, the names of the men were called and Ethel knew that she was listed as Madame Komoru, a thing that made her shiver every time it was brought to her attention.

An exclamation or astonishment escaped the lips of the more impulsive American girl as she came on deck; for as far as the eye could see the gray flat tops of the war vessels were covered with the drab-winged planes, while every few seconds a plane shot into the air and joined an endless winged line that stretched away to the northeast.

"Komoru eighty-five: Oshima eighty-six."

The intent of that command was clear and Ethel was soon settled immediately behind the young secretary in the little bamboo car of a Japanese plane-of-war.

The propeller started with a shrill musical hum; they raced down the runway; dipped for a second toward the water; rose, and sailed swiftly up and on toward the dark line of Mexico, that lay in the evening shadow cast by the curved surface of the Pacific Ocean.

(To be continued.)

Synopsis of Previous Installment: In the year 1958, Ethel Calvert, a daughter of an American grain-merchant, residing in Japan, because of her father's death in an anti-foreign riot, is forced to take refuge with Madame Oshima, the French wife of a Japanese scientist. She becomes accustomed to the mode of living followed by the Japanese, and is finally persuaded to adopt the costume of the land of her exile. War is declared between Japan and the United States, and Professor Oshima, and Komoru, his Secretary, together with Madame Oshima and Ethel Calvert, sail for United States in a Japanese war vessel. When near the Pacific Coast, the many men and women who have been passengers on the vessel, leave the ship by means of aeroplanes, and sail eastwardly over Southern California.

The air cut by Ethel's face at a ninety-mile gait, and she gripped nervously at the hand-rails of the car. Then, regaining confidence, she began to drink in the novel view about her. Ahead were the drab-winged aeroplanes growing smaller and smaller until they became mere specks against the darkening sky. She turned to the rear and watched the myriads of humans, like birds, rising from the transports that still lay in the sunshine. There were literally thousands of them. She wondered if human eyes had ever before witnessed so marvelous a sight.

They had come over the mainland of Mexico now and were flying at a height of about half a mile. Shrouded in the tropical twilight, the landscape below was but dimly discernible. As the darkness came on, Ethel discovered that a small light glowed from the side of the car in front of the driver. Gripping the hand-rail, she made bold to raise herself; and, stopping beneath the searchlight and machine-gun that hung, one beneath the other, on swivels in the center of the framework, she peered forward over Komoru's shoulder.

The taciturn steersman turned and smiled but said nothing. Ethel noted carefully the equipment of the driver's box. It was a duplicate throughout of the dummy steering gear with which she had practiced in the ship's gymnasium. One conspicuous addition, however, was an object illuminated by the small glow lamp that had attracted her attention. This proved to be chart or map mounted at either end on short rollers. As the girl watched it, she perceived that it moved slowly. A red line was drawn across the map and hovering over this was the tip of a metal pointer. A compass and a watch were mounted at one side of the chart case.

Ethel watched the chart creep back on its rollers and reasoned that the pointer indicated the location of the aeroplane. She wondered how the movement of the chart was regulated with that of the plane. Finally she decided to ask Komoru.

"By the landmarks and the time," he said. "Do you see that blue coming in on the northeast corner of the map?"

"Yes."

"Well, watch it."

After a few minutes of waiting the words "Gulf of Mexico" rolled out upon the chart. "Why, that can't be," said Ethel, "we just left the Pacific Ocean."

"But we have crossed the Isthmus of Tehauntepec," replied Komoru; "it is only a hundred miles wide."

His companion looked over the side of the car and to the front and. to the right, she could see by the perfectly flat horizon that they were approaching water.

"The map is unrolling too fast," said Komoru, as the pointer stood over the edge of the indicated water—and he pushed back the little lever on the clock mechanism that rolled the chart. "We have a little head wind," he added.

Ethel resumed her seat and sat musing for a half hour or so. Komoru looked around and called to her.

"Look over to your left," he said. "The lights of Vera Cruz. We are making better time now," he added, again adjusting the regulator on the clock work.

The driver contemplated his compass carefully and shifted his course a few points to the right. Ethel settled in her bamboo cage and pulled her aviation cap down tightly to shield her face and ears from the wind pressure.

For hours they sat so—the girl's heart throbbing with awe, wonder and fear; the man unemotional and silent, a steady, firm hand on the wheel, his feet on the engine controls and his goggled eyes glancing critically at compass or watch or out into the starlit waste of the night, disturbed only by the whirl and shadow of other planes which with varying speed passed or were passed, as the aerial host rushed onward. There were only small tail lights, one above and one below the main plane, to warn following drivers against collision.

With her head bent low upon her knees, Ethel at length fell into a doze. She was aroused by Komoru's calling, and straightening up with a start, she arose and leaned forward over the driver. Komoru was looking intently at the scroll chart. In a moment she designed the cause of his interest, for there had rolled across the forward surface of the chart the outline of a coast.

In the far left-hand corner was marked the city of Galveston, and to the right was the Sabine River that forms the boundary between Texas and Louisiana. Ethel raised her eyes from the map and looked far out to the Northwest. Sure enough, she discerned the lights of a city at the point where Galveston was indicated by the chart.

"How far have we come?" she asked in astonishment.

"Eight hundred miles," replied Komoru. "See, it is nearly two-thirty. The first men with the faster planes were to have arrived at one o'clock."

A little later they passed over the dimly discernible coast line, some thirty or forty miles to the east of Galveston. Komoru carefully consulted his compass, watch and aneroid, and made a slight change in his course.

"Where do we land?" asked the girl.

Komoru steadied the wheel with one hand; and, reaching into the breast pocket of his aviator's jacket, he produced a little document-like roll. "These are the orders," he explained, and asked Ethel to spread out the papers on the chart case.

The instruction sheet read:

"Fly twenty-eight minutes beyond the coast line, which will place you ten or twenty miles northwest of the town of Beaumont, where a fire of some sort will be lighted about 3 a.m.

"When you alight locate one or more farm houses and attach one of the enclosed notices to the door.

"This done, fly toward the Beaumont signal fire and assist in subduing the town and capturing all petroleum works in the region.

"At 6 a.m., if petroleum works are safe, follow the lead of the red plane and fly northwest as far as Fort Worth, returning by nightfall to oil region."

Ethel read the paper over and over as she held it down out of the wind by the dim glow lamp. She wanted to ask questions. She wondered what was expected of her. She wondered again as to what was expected of the entire invasion and why the women had been brought along. But her questions did not find verbal expression, for she had schooled herself to await developments.

The roller chart had now come to a stop and showed the red line that marked their course terminating in a cross to the northwest of the town of Beaumont. Komoru tilted the plane downward and flew for a time near the earth. Then checking the speed, he ran it lightly aground in an open field a little distance from a clump of buildings.

The driver got out and stretched his cramped limbs. Taking a hand glow lamp he ran carefully over the mechanism of the plane. Then he opened a locker and took out two small magazine pistols. One he handed to Ethel.

"Don't use it," he said, "until you have to."

"Will you go with me?" he asked, "to tack the poster, or will you stay with the plane?"

"I'll stay here," she replied.

Komoru walked off rapidly towards the house. Presently the stillness was interrupted by the vociferous barking of a dog; Then there was a sound as of some one picking a taut wire and the voice of the dog curdled in a final yelp.

In a few minutes Komoru was back. "Dogs are no good," he said; "they produce nothing but noise."

"Will you kindly get aboard, Miss Ethel? There is much to do."

Ethel obeyed; meanwhile Komoru inspected the surface of the ground for a few yards in front of the plane. Returning he climbed into his seat and started the engine. They arose without mishap.

Within a mile or two, Komoru picked out another farm house and made a landing nearby.

"I will go with you this time," said Ethel courageously.

Approaching an American residence, Ethel suddenly found herself conscious of the fact that she was dressed in a most unladylike Japanese kimo. For a moment the larger sentiments of the occasion were replaced by the womanly query, "What will people say?" Then she laughed inwardly at the absurdity of her thought.

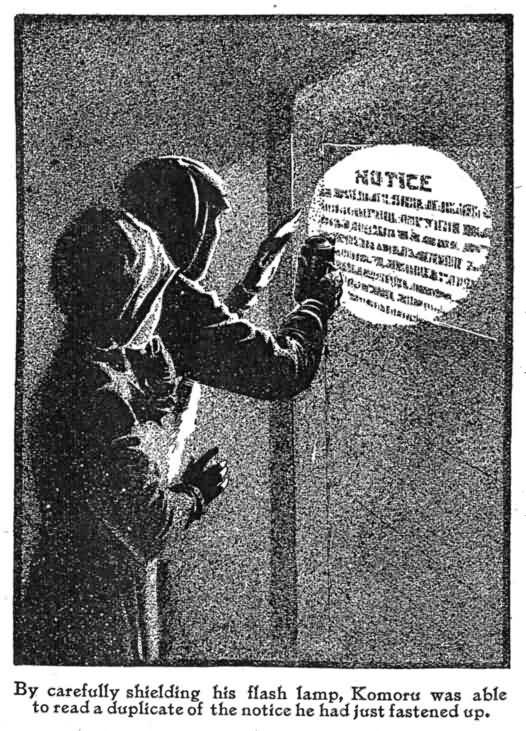

Komoru produced the roll from his pocket and unwound a small cloth poster. This he fastened to the door jam by pressing in the thumb tacks that were sewed in the hem. Then noting another white blotch on the opposite side of the door, he carefully shielded his lamp, and made a light. It was a duplicate of the notice he had just fastened up and read:

"Two hundred thousand Japanese have invaded Texas and are desirous of possessing your property. You are respectfully requested to depart immediately and apply to your government for property elsewhere. All buildings not vacated within twenty-four hours will be promptly burned—unless displaying a flag truce for sufficient reason. Kindly co-operate with us in avoiding bloodshed.

(Signed) The Japanese People."

"We were late," said Komoru as they walked back toward the plane. "Two hundred thousand," he mused; "what you call 'bluff,' I guess."

"It's growing light," said Ethel, as they reached the plane.

"Yes, a little," replied Komoru, as he walked around to the front. "An ugly ditch," he said. "We shall have to use the helicopter."

Taking his seat he threw down a lever and what had appeared to be two small superimposed planes above the main plane assumed the form of flat screws. Letting the engine gain full headway, Komoru threw the clutch on this shafting, and the vertical screws started revolving in opposite directions with a great downward rush of air. The whole apparatus tilted a bit, and then slowly but steadily arose.

When they had reached altitude of a hundred feet or so, the driver shifted the power to the quieter horizontal propeller and the plane sidled off like an eagle dropping from a crag.

Tilting the plane upward, Komoru circled for altitude. Presently he called back over his shoulder, saying that he saw the signal fire at Beaumont at the same time heading the plane in that direction.

As the dawn began to break in the East, the occasional passing lights of flying planes became less bright and soon the planes themselves stood out against the sky like shadows. And then the whole majestic train of aerial invaders became visible as they poured over the southern horizon—-a never ending stream.

Komoru and Ethel landed in a meadow already well filled with planes and following the others, hurried along toward the town.

There had been some fighting in the streets and a few buildings were burning. Walking along to the main street of the town, they came upon a crowd of Japanese who were collected in front of a building from which the contents were being dragged hastily.

"What is it?" asked Komoru of one of the men.

"Hardware store," replied the other; "we've rifled all of them for the weapons and explosives."

"Where are all the people?" asked Ethel. "The Americans—are they killed or captured?"

"They are at home in their houses," answered the man, who seemed well posted. "I was with the first squad to arrive. We captured the policemen and then took the telephone switchboard. Japanese operators are in there now. They have called up every one in town and explained the situation, and advised the people to stay indoors, telling them that every house would be burned from which people emerged or shots were fired. The operators are working on the rural numbers yet. We hold the telegraph also, and are sending out exaggerated reports of the size of the Japanese invasion."

A man wearing a blue sash came hurrying up. He stopped before the group at the hardware store and gestured for silence.

"The town is well in hand," he said, "and only those of you who are detailed here as guards need remain longer; the others will get back to their planes and await the rise of their designated leaders for the flights of the day.

"Come," said Komoru to his companion. But Ethel did not move. Her mind was racked with perplexity. Here she was in a city of her own people. Why should she continue to accompany this young Japanese whom, despite his gentlemanly conduct, she instinctively feared? Yet what else could she do? She was dressed in the peculiar attire of the invaders, and would certainly have trouble in convincing an American of her identity.

"I must ask you to hurry," said Komoru, as the others moved off. With an effort Ethel gathered her wavering emotions in hand and went with him. If she must go, she reasoned it were well not to arouse Komoru's suspicion of her loyalty.

A few minutes later they were again in the air, following the lead of a plane with bright red wings—the flag-ship, as it were, of the group.

In a half hour the expedition was approaching Houston. Coming over the city, the leader circled high and waited until his followers were better massed.

"Are we going to attack the town?" inquired Ethel, as Komoru asked her for the water-bottle.

"Oh, no," he replied, "nothing of the sort; we are simply bluffing. There are a number of expeditions going out to-day. We must make the appearance of a great invasion."

"How many planes are there all told?"

Komoru smiled. "Not so many," he said.

"But how many?" persisted Ethel.

"Fifteen thousand, maybe," Komoru replied.

"To invade a country with nearly two hundred million inhabitants! We will surely all be killed."

Komoru smiled.

"By sheer force of numbers," explained Ethel.

"Wait and see," replied her enigmatical companion.

For hours the little aerial squadron sailed through the balmy air of Texas. They passed over Austin and Waco and Fort Worth and Dallas. They turned eastward and passed over Texarkana, and thence south to impress the people of Shreveport.

The excitement evinced in the towns increased as the news of their flight was wired ahead. They were frequently shot at by groups of excited citizens or occasional companies of militia, but at the height and speed at which they were flying the bullets went wide. One plane was lost. Something must have snapped. It doubled up and went tumbling downward like a wounded pigeon.

The sun was dropping toward the western horizon. The invaders had been flying for ten hours. They had been without food or sleep for thirty-six hours. Save for the brief relaxation of the morning, Komoru had not taken his hands from the steering wheel, nor his foot from the engine control since the previous sunset in the Bay of Tehauntepec.

As they passed near other planes, Ethel noted that in many cases the women were driving. Notwithstanding her dislike for him, the girl found herself wishing that she could relieve Komoru.

She pondered over his "wait and see" and began to discern a new possibility in an invasion of thirty thousand Japanese. She tried to imagine one of the society favorites of her Chicago girlhood sitting in front of her driving that plane. She remembered distinctly that aeroplane racing was a part of the diversion of such men and that five or six hours of driving was considered quite a feat.

The more she considered the man before her, the more she marvelled at his powers. She confessed he interested her; she wondered why she disliked him. The only answer that seemed acceptable was that he was "not her kind."

Towards dusk, they hove in sight of the derricks of the Beaumont oil region. The leader with the red plane descended in a large meadow. Komoru was well to the front and brought his plane to earth a few meters from the red wings. The man in the flag plane who had that day led them over a thousand miles and a score of cities got out and stretched himself. With an exclamation of joyful surprise, Ethel recognized that he was Professor Oshima.

The Japanese camped where they were for the night. The wings of the planes were guyed to the ground with cordage and little steel stakes. Beneath such improvised tents the tired aerial cavalrymen rolled themselves in their sleeping blankets and for twelve hours the camp was as quiet as a graveyard.

That day had been a great day in history; it was the first consequential aerial invasion that the world had ever known. While the arrivals of the morning had been circling in fear-inspiring flights above the neighboring states, the later starters from the Japanese squadron had continued to arrive in the oil regions. Like migrating birds, they settled down over the rich fields and grazing lands of that wonderful strip of flat, black-soiled prairie that stretches westward from the south center of Louisiana until it emerges into the great semi-arid cattle plains of southern Texas.

The region, though one of the richest in the United States, was but sparsely settled. Save for the few thousand white laborers who were supported by the oil industry, the whole resident population were negroes who were worked under imported white foremen in the rice and truck lands of the region.

The negroes were panic stricken by the Japanese invasion and made practically no resistance. In two or three days, the country for a forty-mile radius around Beaumont was cleared of Americans and practically the entire oil region of Texas with its vast storage tanks at Port Arthur on the Sabine River, were in the hands of the invaders.

There were not ten regiments of American soldiers within five hundred miles. The great mass of the American army had been rushed weeks before to southern California, and the remnant left in the Gulf region had more recently been hastened to Panama. In fact, the American squadron had steamed into Colon on the very morning the Japanese alighted on Texas soil.

On the second morning of their arrival, Japanese officials circling above the captured region, roughly allotted the land to Captains under whose leadership were a hundred planes each. The captains then assigned each couple places to stake their plane, which were located a hundred meters apart, allowing to each about two and a half acres of land.

Professor Oshima and Komoru, as soil chemists, were constantly on the go making studies of the land and advising with the other experts as to the crops to plant, and the methods of tillage for the various locations.

In the cotton lands, where Ethel and her associates were located, the soil was immediately put to a fuller use. The cotton plants were thinned and pruned and between the rows quick growing vegetables were planted. Elsewhere the great pastures were broken up with captured kerosene-driven gang plows and by dint of hard labor the sod was quickly reduced to a fit state for intensive cultivation.

The outside work of the professor and his secretary threw Ethel altogether in the company of Madame Oshima. For this fact she was very grateful, as her aversion to Komoru, to whom she was nominally bound, grew more and more a source of worry and fear. So the two women of Aryan blood worked together in the cotton field side by side with the Orientals—worked and waited and wondered what was awing in the surrounding world.

The gasoline wagons came around and refilled the fuel tanks of the planes. Mechanics inspected the engines carefully and replaced defective parts. The rice cakes and soyu brought from Japan, had been replaced by a diet of wheat and maize products and fresh fruits and vegetables taken from the captured stores and gardens. Such captured foods, however, had all been inspected by the dieteticians, and those of doubtful wholesomeness destroyed or placed under lock and key to be used only as a last resort.

Thus weeks passed. The green things of Japanese planting had poked their tender shoots through the black American soil. There had been no fighting except in few cases, where a company of foolhardy militia or a local posse had tried to attach the Japanese outposts. American aeroplanes had wisely staid away.

But the fight was yet to come. The Federal Government had recalled its ships from Panama and was bringing back the soldiers from California. On the great flat prairie between Galveston and Houston, a mighty military camp was being established. Aeroplane sheds were erected and repair shops built. Long lines of army tents were pitched in close proximity. Army canteens were established that the thirsty soldiers might get pure liquor and good tobacco and a few rods away—over the line—other grog shops were opened wherein were sold similar goods not so guaranteed. Gambling sharks arrived and set up shell games and bedraggled prostitutes—outcasts from urban centers of debauchery—-came and camped nearby and made night hideous with their obscene revelry.

So the American soldier prepared for battle against the enemy who, fifty miles away, slept undisturbed in the midst of gardens beneath the wings of their aeroplanes.

Never since Roman phalanx moved against the hordes of disorganized barbarians had such extremes of method in warfare been pitted against each other. Indeed it is doubtful if the invasion of the Japanese should be called war at all. They were not blood-thirsty. In fact, the Japanese invaders had sent word to the American Government asserting their peaceful intentions if they were unmolested, though threatening dire vengeance by firing cities and poisoning water supplies if they were attacked.

Madame Oshima shook her head. "Such talk is only pretense," she said, "the Japanese intend to live in America and would never so embitter the people—and it will not be necessary."

Ethel was in doubt. She pictured the Japanese planes flying above the unprotected inland cities dropping conflagration bombs upon shingled roof or casks of prussic acid into open reservoirs. She wished she were out of it all. She wanted to escape and yet she knew not how.

The Americans made no hasty attacks. They feared the threats of the Japanese and awaited the gathering of many hundred thousand soldiers. At the end of four weeks the American army was spread in a giant semi-circle surrounding the Japanese encampment from coast to coast. Along the Gulf Coast was also a line of American battleships, so that the Japanese encampment was entirely surrounded with an almost continuous line of aeroplane destroying guns.

All preparations were at last complete and with cavalry beneath and aeroplanes above, the American strategists planned a dash across the Japanese territory with the belief that the outlying lines of artillery would bring to earth those that succeeded in getting into the air.

One evening at the hour of twilight, messengers passed rapidly among the Japanese distributing maps and orders to prepare for flight.

Late that night, their possessions made ready for flight, Komoru and Ethel sat with Professor and Madame Oshima beneath the latter's plane.

"Our scouts have come to the conclusion," said Oshima, "that a cavalry attack is to be expected in the early morning. So our plan is for a signal plane to rise at two o'clock directly over the center of our territory. It will carry a bright yellow light. Beginning with the outlying groups our forces are to fly toward the light, rising as they go. Attaining an altitude of two miles they are thence to fly due north as our maps show. We will suffer some loss, but two miles high and at night I guess American gunners will not inflict great damage."

Ethel shuddered.

"Do you think the American aviators will follow us?" asked Komoru.

"That depends," replied the older man, "upon the reception we give them; we have them outnumbered."

"They carry men gunners," said Madame Oshima.

"So," said the Professor, "but shooting from an aeroplane depends not so much upon the gunner as upon the steersman. Their planes wabble, the metal frame work is too stiff, it doesn't yield to the air pressure."

Along such lines the conversation continued for an hour or so. Neither the men nor Madame Oshima seemed the least bit excited over the prospects; but Ethel, striving to keep up external appearances, was inwardly torn with warring emotions.

Making an excuse of wishing to look for something among her luggage, the girl finally escaped and walked quickly toward the other plane. But instead of stopping, she passed by and continued down between the rows of cotton, avoiding as much as possible the lights that dotted the field about her.

"Oh, God!" she repeated under her breath; "Oh, God! I can't go! I won't go!"

For some time she walked on briskly trying to calm her feverish mind and reason out a sane course of procedure.

She was passing thus where the lights of two planes glowed fifty meters at either side, when she stumbled heavily over some dark object between the cotton rows. She turned to see what it was; and, bending forward, discerned in the starlight the body of a man. She started to run; then, fearing pursuit the more, checked her speed. As she did so some one grasped her arm and a heavy hand was clapped over her mouth.

"Keep quiet," commanded her captor hoarsely. In another instant he had bent her back over his knee and thrown her—or rather dropped her for she did not resist—upon the soft earth beneath.

"If you make a sound, I'll have to shoot," he said, resting a heavy knee upon her chest and clasping her slender wrist in a vise-like grip of a single hand.

The girl breathed heavily.

The man reached toward his hip pocket and drawing forth a bright metallic object held it close to her face. Her breath stopped short. Then a flood of light struck her full in the eyes, as her captor pressed the button on his flash lamp.

"God! a woman!" the man gasped. The exclamation and voice were clearly not Japanese.

Ethel felt the grip loosen from her wrists and the weight shift from her chest.

"You're no Japanese!" he said under his breath, at the same time letting the glowing flash lamp fall from his hand.

Presently Ethel raised her head and reached for the lamp where it lay wasting its rays against the black soil. She now turned the glow on the other and saw kneeling beside her a young man in American clothes. He was hatless and coatless and his soft gray shirt was torn and mud bespattered. A massive head of uncombed hair crowned a handsome forehead, but the face beneath was marred by a stubby growth of beard.

"Who are you?" whispered Ethel finding her voice.

"Put out the light," he commanded, reaching forward to take it from her.

"Who are you?" he asked reversing the query as they were again in darkness.

"I'm a girl," said Ethel.

The man laughed softly.

"I'm not," he said.

Ethel drew herself into a sitting posture. "Which side of this war are you on?" she asked.

The man was afraid to commit himself—then a happy thought struck him. "The same side that you are," he answered diplomatically.

It was Ethel's turn to smile.

"You are an American?" she ventured at length.

"Yes," he said. "So are you?"

"Yes."

"Then why are you wearing Japanese clothes?"

"Because—" she said hesitatingly, "I haven't any others."

For some minutes he said nothing.

"Are you going to give the alarm of my presence?" he asked at length.

"No."

"Then I'll go," he said.

Rising from his knees, but still stooping, he made off rapidly down the cotton row.

Ethel breathed deeply. Confused thoughts flashed through her mind. She would not return to go with Komoru; in her Japanese garb she feared the early morning sweep of American cavalry; but to the man who had just left her, why could she not explain?

Without further debate, she arose, and at top speed ran after the retreating figure.

The next instalment of this absorbing tale will appear in the September issue of PHYSICAL CULTURE. It tells of how the Japanese attempt to obtain control of the United States through scientific measures rather than barbarous warfare, and is wonderfully interesting and readable. Don't miss it.

SYNOPSIS: In the year of 1958, Ethel Calvert, a daughter of an American grain-merchant, residing in Japan, because of her father's death in an anti-foreign riot, is forced to take refuge, with Madame Oshima, the French wife of a Japanese scientist. She becomes accustomed to the land and mode of living followed by the Japanese, and is finally persuaded to adopt the costume of the land of her exile. War is declared between Japan and the United States, and Professor Oshima, and Komoru, his Secretary, together with Madame Oshima and Ethel Calvert, sail for the United States in a Japanese war vessel. When near the Pacific Coast, the many men and women who have been passengers on the vessel, leave the ship by means of aeroplanes, and sail eastwardly toward Texas, where they establish plantations and conduct a desultory warfare by aeroplanes with United States troops. While working in the fields Ethel discovers a young American in concealment. He warns her to keep silent, and immediately runs away.

In a few minutes Ethel had caught up with the man who, more cautiously, ran before her. Checking her speed, she followed silently.

For a half-mile she pursued him thus. He came to the end of the field and dodged into the thicket of bushes that lined the fence row. He moved more slowly now, and she followed by sound rather than by sight. At length they came to where a brook ran at right angles to the fence row. The man stopped and crawled under the barbed-wire fence and came out on the turnpike that ran alongside.

Ethel, peering out from the bushes, saw him walk boldly forward and stand upon the end of the stone culvert that conducted the brook beneath the roadway. For a moment only he remained so, and then clambered quickly down at the end of the arch and disappeared in the darkness beneath. She heard a foot splash in the water, and then all was quiet save the gurgle of the stream.

Climbing over the fence, she top ran forward upon the culvert. She listened and looked toward either end, resolved to call to him if he emerged.

As she stood waiting she saw the yellow signal light rise in spirals higher and higher and then circle slowly in one location. A few minutes later the dim tail lights of the planes came up out of the horizon and flew towards the signal light.

After a half-hour of waiting, she boldly resolved to enter the hiding place of the man she had followed.

Cautiously feeling her way, she clambered down over the end of the culvert and peered into its black archway.

At first, dimly and then with brighter flash, she saw a light within. Creeping slowly forward, wading in the stream and stumbling over rough blocks of stone, she made toward the light. Midway the passage, the side wall of the culvert had fallen or been torn down and there in a little damp clay nook, sitting hunched upon a rock was the silhouette of the unshaven man.

Beyond him glowed the dim light and by its faint rays he was hurriedly writing in a note book.

With a start he became aware of her presence, and turned the flash-light upon her.

"I followed you," she stammered. "I want to explain. I'm an American girl captive among the Japanese."

He stared at her quizzically in the dim light.

"I ran from you," he said, "because I was afraid to trust you—there are a number of Europeans among the Japanese forces. I couldn't know that you wouldn't have given the alarm, and for one man to run from fifty thousand isn't cowardice; it's common sense—even bravery, perhaps, when there's a cause at stake."

"I understand," replied the girl.

"Won't you be seated?" he said, arising and offering her his place on the rock. She accepted, and he asked her for more of her story.

In reply she told him whom she was and related as briefly as she could the incidents of her life that accounted for her peculiar predicament.

"I suppose I owe you something of an explanation, too;" he said, when she had finished. "My name is Winslow—Stanley Winslow; I am —or at least was—-the editor of the Regenerationist. Do you know what that is?"

Ethel confessed, that she did not.

"Perhaps I flatter myself, but then I suppose you have had no chance to keep up on American affairs."

Just then a crash, followed by a whirring, clattering noise broke in above the sound of the man's voice and the gurgle of the brook running through their hiding-place.

"What's that?" Winslow exclaimed, starting towards the end of the culvert.

Ethel followed him. Before they reached the open the trees in front of them were lit up by the lurid light of a fire. Beside the road a hundred yards away was the crumpled mass of a metallic aeroplane. The gasolene tank had burst open and was blazing furiously.

"Americans," said Winslow; "let's see if the crew are dead."

The gasolene had largely spent itself by the time they reached the plane.

Poking about in the crumbled debris, they found the driver impaled upon a lever that protruded from his back.

"I wonder what grounded her," mused Winslow, as he inspected the dead man with his flash-lamp. "Oh! here we are! Good shooting that," he added, pointing with his lamp to a soggy hole in the side of the man's head.

"I guess they're at it," he said, pressing out his light and turning his eyes skyward.

The woman, speechless, followed his gaze. Across the sky flashed here and there brilliant beams of search-lights, but far more numerous were the swiftly moving star-like tail-lights of the Japanese planes.

Now and again they heard the crackling of machine guns, occasionally the burr of a disordered propeller and once the faint call of a human voice.

"Look," said Ethel, pointing to the southward. "See that brilliant yellow light. It's the Japanese signal plane; they are all to fly in towards it, and then, soaring high will escape over the American lines."

"The lines are a joke," returned Winslow. "It's plane against plane. And the Japs will get the best of it; or at least they'll get away, which is all they want. They are going to Dakota, where five train loads of gasolene will be setting on a siding waiting to be captured. We printed the story ten days ago, though the administration papers hooted at the idea."

As they walked back toward the culvert, Ethel stumbled over something in the roadway. She asked for the light, and discovered to her horror that she was standing in the midst of the remnants of a man who had been spattered over the hard macadam of the turnpike.

"Ugh! take me away," she shuddered, averting her eyes and running toward the stream,

"The gunner fell out of the plane when she lurched, I guess," commented Winslow to himself, examining the shreds of clothing attached to the mangled remains beneath him.

For some reason Winslow did not immediately follow the girl but went back and looked over the wrecked plane again.

He removed the magazine pistol from the impaled man's pocket and searched about in the locker until he found a supply of cartridges.

The sky was beginning to brighten from approaching dawn now, and the searchlight flashes were less brilliant. Winslow stood gazing upward until the forms of the lower flying planes became visible. Suddenly he saw a disabled plane come somersaulting out of the air and fall into a field quarter of a mile away. Evidently there were explosives aboard, for a shower of flame, smoke and splinters arose where she fell.

The onlooking man hopped over the fence and ran toward the spot. There was little to be seen—a mere ragged hole in the sod. As he unconcernedly walked back he passed at intervals a propeller blade sticking upright in the soil, a broken can of rice cakes and a woman's hand.

The dawn had now so far progressed that the observer could see some order in the movement of the air craft. He studied with fascination the last of the Japanese planes as they circled up toward their aerial guide-post and moved thence in a steady stream to the northward.

The American planes which had been harassing and firing on the Japanese as they circled for altitude, now turned and closed in on the rear of the enemy and the fighting was fast and furious. Plane after plane tumbled sickeningly out of the sky. But for Winslow the sight lasted only a few minutes, for the combatants were flying at full speed and soon became mere flitting insects against the gray light of the morning sky.

Striding down the roadway past the mangled body of the American gunner, Winslow reached the culvert.

Ethel Calvert was sitting on a flat stone at the edge of the water. She held her woven grass sandals in her hands and was washing them by rubbing the soles together in the stream.

As Winslow looked down at her in silence, the girl looked up and eyed him curiously. Neither spoke. The man stooped and washed his hands in the brook and then stepping up-stream a few paces he drank from the rivulet.

Returning he regarded the girl. She had placed her sandals beyond her on the grassy bank and sat with her bare feet in the shallow stream. Her head, buried in her arms, rested upon her knees. The slender shoulders now shook convulsively and the sound of a sob escaped her. In the calmness of his cynicism, the man sat down on the rock and placed a strong arm around the trembling woman.

"I know," he said, "it's a dirty damned mess, but we didn't start it."

After a time the girl raised her head. "I know we didn't start it," she said; "but isn't there something we can do to stop it?"

"Well," he replied slowly, "I rather hope to have a hand in stopping it, and perhaps you can help."

"How?"

"Surely you can do as much in stopping it as one of those poor devils that get smashed does in keeping it going," he went on.

"How?" she repeated.

"Well, that's quite a long story," he replied; "if you don't already know."

"I told you who I was."

"Yes."

"Well, the Regenerationists, along with many other sincere men and women in this country tried to prevent this war and are trying to get it peaceably settled now. The Japs don't want to die. They want a chance to live. We've got a lot of vainglorious, debauched, professional soldiery that wanted to fight something, and now they're getting their fill. In the first place, there is no need of war and in the second place, when there is war, the same stamina that will make efficient humans for the ordinary walks of life will make good soldiers. But money talks louder than reason. The ruling powers in American government are a crew of beer-bloated politicians who are in the pay of a cabal of wine-soaked plutocrats, and the American people under such administration have become a race of mental and physical degenerates. The Japs knew this or they would never have invaded the country."

"What are you going to do about it? And what are you doing here now within the Japanese lines?" asked Ethel when her companion paused.

"Oh, I am acting as my own war correspondent," he replied, smiling a little.

"Pat-a-pat, pat-a-pat"—Winslow jumped up excitedly and clambered to the top of the embankment.

Ethel noting his alarm, slipped her feet into her sandals and rose to follow him.

"Quick," he exclaimed, hurrying down the bank again. "It's American cavalry."

"But let us go meet them," said the girl.

"No, never," replied Winslow, taking her by the arm and hurrying her into the culvert. "You don't understand. As for you in kimo, your reception would be anything but pleasant; and as for me, I'm an outlaw with a price on my head."

Reaching the chink where the rocks had fallen out of the culvert wall, Winslow squeezed into it and pulled the girl down beside him. Carefully he crowded her feet and his own back so that their presence could not be detected from the end of the culvert.

"I'm afraid we left tracks on the bank, but we can at least die game," he said, pulling his magazine pistol from his belt and handing it to the girl, while he drew from his hip pocket the weapon he had taken from the dead aviator.

"I hate these things," he said, "but when a man is in a corner and no chance to run, I suppose he's justified in using a cowardly fighting machine."

They heard clearly now the hoof beats on the roadway above. Presently an officer rode his horse down to the stream at the head of the culvert. "Anything under there?" called a voice from above.

"Nothing doing," replied the other, peering beneath the archway.

"You're a fool sitting there like that," called a third voice. "Company C lost two men back there from a wounded Jap under a bridge."

The horseman urged his beast up the bank and the troop passed on.

For some hours the man and the girl remained in the culvert; meanwhile Winslow explained the Regenerationist movement, which was not as his enemies interpreted, a traitorous party favoring the Japanese, but only a group of thinkers who advocated principles not unlike those which had made the Japanese such a superior race either at peace or at war.

As she listened, it seemed to Ethel as if her own dream had come true, for here indeed was a man of her own blood with stamina of physique and mental and moral courage, who professed and practiced all she had found that was good among the people of her enforced adoption and in addition much that, to her with her racial prejudice in his favor, seemed even better than the ways of Japanese.

In reply to her questions as to the cause of his outlawry, Winslow explained that he and other leaders of his party had long been at swords' points with the conservatives who were in power and that the administration, taking advantage of the martial frenzy of the war, were persecuting the Regenerationists as supposed traitors.

As the sun indicated mid-forenoon the dishevelled editor of the Regenerationist and his newly found follower sauntered forth and took to the turnpike.

"We may as well be on the road," he argued. "The sooner the American people get the inside facts of this affair the sooner they will decide to stop it, and it's forty-five miles to the nearest place where I can get in touch with my people."

Bareheaded, through the hot sun, they travelled rapidly along the turnpike, keeping a sharp lookout for occasional parties of cavalry and hiding in the fields until they passed. Sometimes they talked of the contrasted ways of life in Japan and in America, and again Winslow wrote hurriedly in his note-book as he walked.

About three o'clock in the afternoon they stopped in the shade where a rivulet fell over a small cataract.

"Aren't you hungry?" asked Ethel, after they had drunk from the brook.

"I don't know. I hadn't thought of it particularly," replied her companion. "Let's see, the last time I ate was in a farmhouse north of Houston. That was eight days ago. When have you last eaten?"

"Yesterday morning," replied the girl.

"Then you are probably hungrier than I am."

With their conversation and the murmur of the waterfall they had failed to detect the approach of two cavalry officers, who, walking their tired mounts, had come up unheeded.

"Hey! look at the beauty in breeches!" called one of the approaching men.

"Her for mine," returned the other.

"I saw it first—hie!" returned the first, drawing rein.

"Give it to me, you hog; you've got one!"

"All right, all right—go take it—maybe the bum will object," laughed the first, as the unshaven Winslow advanced in front of the girl.

"Run quick," called Winslow to Ethel. "They're too drunk to shoot straight."

The turnpike was inclosed by a high, woven-wire fence, and the girl obeying turned down the road. Her would-be claimant put spurs to his horse and dashed after her, leaving Winslow covering the rear horseman with his magazine pistol.

"Well," said the drunken officer weakly, "I ain't doing nothing."

"Then ride down the road the other way as fast as you can go."

The officer obeyed.

For a moment Winslow watched him and then turned to see Ethel climbing over the woven-wire fence with the soldier trying to urge his horse up the embankment to reach her.

Winslow started to run to the girl's rescue, but no sooner had he turned than a bullet sang past his ear. Wheeling about he saw the other cavalryman riding toward him firing as he came.

With lewd brutality calling for vengeance in one direction and a man firing at his back from the other, Winslow's aversion to bloodshed became nil; and, aiming cool, he began firing at the approaching officer.

It must have been the horse that got the bullet, for with the third shot mount and rider somersaulted upon the macadam.

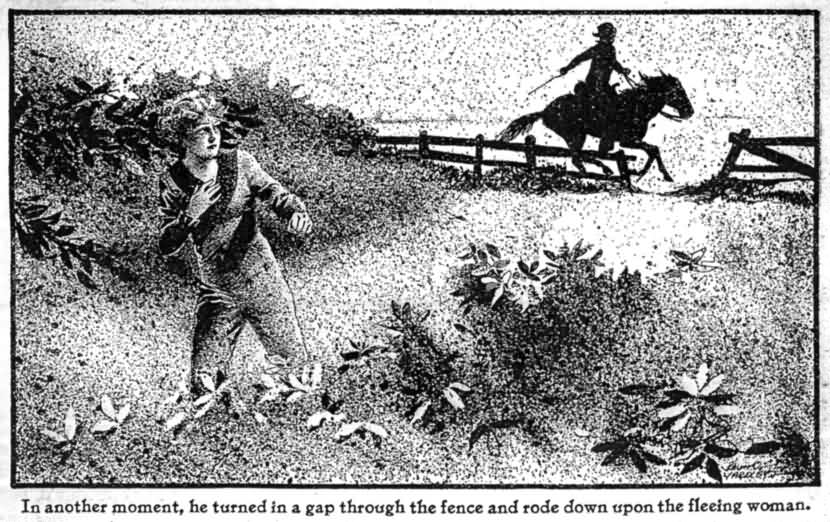

Without compunction, Winslow turned and sprinted down the roadway. He saw Ethel dashing across the field, hurdling the cotton rows. The officer was racing down the road, seeming away from her, but in another moment he turned through a gap in the fence and rode down upon the fleeing woman.

The athletic Winslow vaulted the six-foot fence with an easy spring, and tore madly through the obstructing vegetation.

The rider overtaking the woman, tried to hold her, first by the arm, and failing in that, he grabbed her by the hair. Winslow wondered why she did not shoot him, and then he recalled that he was carrying both weapons.

In another instant he was up with them and had dragged the man from his horse and flung him to the ground. The soldier kicked and swore, but half drunk, his resistance was of small consequence to his well-trained adversary.

"Here," called Winslow to the girl, who had tumbled down in a heap more from fright than physical exhaustion, "come and get my knife and cut the rein from the horse's bridle."

Thus equipped, the two strapped their captive's hands and one foot together behind him.

"There now," said Winslow, as he relieved the officer of his weapon. "Hop back to the bridge and look after your comrade. He fell on the turnpike a while ago and I'm afraid he hurt his head. We'll have to be going."

"Shall we take the horse?" asked Ethel.

"No," replied her companion, beginning to throw clods at the animal, "we'll simply run him away. As for us, we are safer on foot, and will in the long run make better time."

"You are not tired, are you?" he asked, as they turned into the roadway again.

"No," she replied, "only a bit tired and weak from my scare. How far have we come?"

"Fifteen miles, perhaps; I really hardly know; we've been interrupted so much."

They made a long detour through the fields to avoid a group of buildings. Striking the road again, they soon came upon a slight rise of land that stood well above the level of the surrounding country.

"Are we not rather conspicuous here?" asked the girl.

"Well, rather," admitted her companion, pausing to look around; "but I guess we can see as far as we can be seen."

"Look! look!" called Ethel excitedly, jerking her companion's arm and pointing to the south, where the flat horizon was broken by the derricks and tanks of the oil fields.

At first Winslow saw nothing, and then shading his eyes he sighted what looked like a great bevy of birds flying just above the horizon.

Larger and larger grew the specks against the sky.

"They will be over us in fifteen minutes," said Winslow; "let's get up in that oak over there, where we can see without being seen."

Safely hidden by the enveloping foliage, the man and the girl now watched the approach of the planes. As they came over the oil region the planes began swooping near the ground and then rapidly rising again.

"Its Japanese after the American cavalry, I guess," said Winslow. In a few minutes black smoke belched forth at numerous points from the petroleum works.

After a time a cloud of dust arose from a great meadow that spread for several miles to the north of the oil wells. A group of aeroplanes hovered closely above the dust cloud and kept up that periodical swooping towards the earth.

"It's stampeding cavalry," said the sharp-eyed Ethel, "and the airmen are dropping bombs on them."

The cloud of dust came nearer and nearer until they could see the swift fall of the deadly missiles from the swooping planes and the havoc wrought in the straggling ranks by the showers of pellets from the shrapnel exploding above their heads.

When the foremost of the cavalry troop were perhaps a quarter of a mile from the observers, a commanding officer, who was riding well in the lead, wheeled his horse, threw away his jacket, tore off his white shirt and waived it frantically above his head.

An answering truce flag soon appeared from a plane above and the jaded horsemen, riding up, drew rein and waited.

The truce plane now swooped low and dropped a message fastened to a white cloth. A soldier caught it and brought it to the officer, who signalled assent.

Orders were called along the line, and the men filed by and piled their weapons in an inglorious heap.