When a work of fiction has reached its fortieth edition, one would suppose the author might congratulate himself upon having contributed something of an imperishable character to the literature of the country. But no such pretensions are asserted for this production, now in its fortieth thousand. Being the first essay of an impetuous youth in a field where giants even have not always successfully contended, it would be a rash assumption to suppose it could receive from those who confer such honors any high award of merit. It has been before the public some fifteen years, and has never been reviewed. Perhaps the forbearance of those who wield the cerebral scalpels may not be further prolonged, and the book remains amenable to the judgment they may be pleased to pronounce.

To that portion of the public who have read with approbation so many thousands of his book, the author may speak with greater confidence. To this class of his friends he may make disclosures and confessions pertaining to the secret history of the “Wild Western Scenes,” without the hazard of incurring their displeasure.

Like the hero of his book, the author had his vicissitudes in boyhood, and committed such indiscretions as were incident to one of his years and circumstances, but nevertheless only such as might be readily pardoned by the charitable. Like Glenn, he submitted to a voluntary exile in the wilds of Missouri. Hence the description of scenery is a true picture, and several characters in the scenes were real persons. Many of the occurrences actually transpired in his presence, or had been enacted in the vicinity at no remote period; and the dream of the hero—his visit to the haunted island—was truly a dream of the author’s.

But the worst miseries of the author were felt when his work was completed; he could get no publisher to examine it. He then purchased an interest in a weekly newspaper, in the columns of which it appeared in consecutive chapters. The subscribers were pleased with it, and desired to possess it in a volume; but still no publisher would undertake it,—the author had no reputation in the literary world. He offered it for fifty dollars, but could find no purchaser at any price. Believing the British booksellers more accommodating, a friend was employed to make a fair copy in manuscript, at a certain number of cents per hundred words. The work was sent to a British publisher, with whom it remained many months, but was returned, accompanied by a note declining to treat for it.

Undeterred by the rebuffs of two worlds, the author had his cherished production published on his own account, and was remunerated by the sale of the whole edition. After the tardy sale of several subsequent editions by houses of limited influence, the book had the good fortune, finally, to fall into the hands of the gigantic establishment whose imprint is now upon its title-page. And now, the author is informed, it is regularly and liberally ordered by the London booksellers, and is sold with an increasing rapidity in almost every section of the Union.

Such are the hazards, the miseries, and sometimes the rewards, of authorship.

J.B.J.

Burlington, N.J.,

March, 1856.

Glenn and Joe—Their horses—A storm—A black stump—A rough tumble—Moaning—Stars—Light—A log fire—Tents, and something to eat—Another stranger, who turns out to be well known—Joe has a snack—He studies revenge against the black stump—Boone proposes a bear hunt.

Boone hunts the bear—Hounds and terriers—Sneak Punk, the hatchet-face—Another stump—The high passes—The bear roused—The chase—A sight—A shot—A wound—Not yet killed—His meditations—His friend, the bear—The bear retreats—Joe takes courage—Joe fires—Immense execution—Sneak—The last struggle—Desperation of the bear—His death—Sneak’s puppies—Joe.

Glenn’s castle—Mary—Books—A hunt—Joe and Pete—A tumble—An opossum—A shot—Another tumble—A doe—The return—They set out again—A mound—A buffalo—An encounter—Night—Terrific spectacle—Escape—Boone—Sneak—Indians.

The retreat—Joe makes a mysterious discovery—Mary—A disclosure—Supper—Sleep—A cat—Joe’s flint—The watch—Mary—The bush—The attack—Joe’s musket again—The repulse—The starting rally—The desperate alternative—Relief.

A strange excursion—A fairy scene—Joe is puzzled and frightened—A wonderful discovery—Navigation of the upper regions—A crash—No bones broken.

A hunt—A deer taken—The hounds—Joe makes a horrid discovery—Sneak—The exhumation.

Boone—The interment—Startling intelligence—Indians about—A skunk—Thrilling fears—Boone’s device.

Night—Sagacity of the hounds—Reflection—The sneaking savages—Joe’s disaster—The approach of the foe under the snow—The silent watch.

Sneak kills a sow that “was not all a swine”—The breathless suspense—The match in readiness—Joe’s cool demeanour—The match ignited—Explosion of the mine—Defeat of the savages—The captive—His liberation—The repose—The kitten—Morning.

The dead removed—The wolves on the river—The wolf hunt—Gum fetid—Joe’s incredulity—His conviction—His surprise—His predicament—His narrow escape.

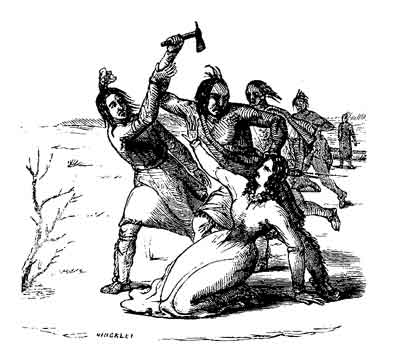

Mary—Her meditations—Her capture—Her sad condition—Her mental sufferings—Her escape—Her recapture.

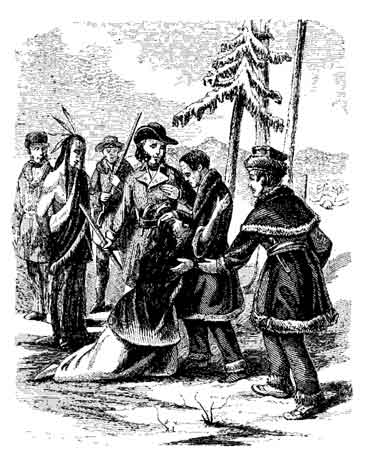

Joe’s indisposition—His cure—Sneak’s reformation—The pursuit—The captive Indian—Approach to the encampment of the savages—Joe’s illness again—The surprise—The terrific encounter—Rescue of Mary—Capture of the young chief—The return.

The return—The young chief in confinement—Joe’s fun—His reward—The ring—A discovery—William’s recognition—Memories of childhood—A scene—Roughgrove’s history—The children’s parentage.

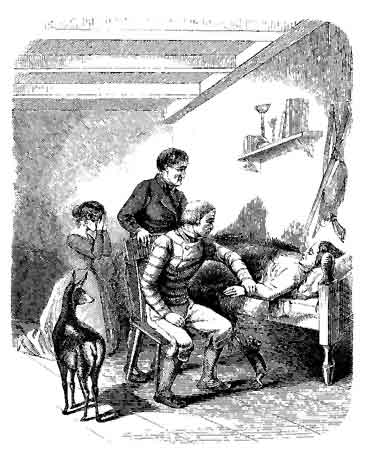

William’s illness—Sneak’s strange house—Joe’s courage—The bee hunt—Joe and sneak captured by the Indians—Their sad condition—Preparations to burn them alive—Their miraculous escape.

Glenn’s History.

Balmy Spring—Joe’s curious dream—He prepares to catch a fish—Glenn—William and Mary—Joe’s sudden and strange appearance—La-u-na, the trembling fawn—The fishing sport—The ducking frolic—Sneak and the panther.

The bright morning—Sneak’s visit—Glenn’s heart—The snake hunt—Love and raspberries—Joe is bitten—His terror and sufferings—Arrival of Boone—Joe’s abrupt recovery—Preparations to leave the West—Conclusion.

Glenn and Joe—Their horses—A storm—A black stump—A rough tumble—Moaning—Stars—Light—A log fire—Tents, and something to eat—Another stranger, who turns out to be well known—Joe has a snack—He studies revenge against the black stump—Boone proposes a bear hunt.

“Do you see any light yet, Joe?”

“Not the least speck that ever was created, except the lightning, and it’s gone before I can turn my head to look at it.”

The interrogator, Charles Glenn, reclined musingly in a two-horse wagon, the canvas covering of which served in some measure to protect him from the wind and rain. His servant, Joe Beck, was perched upon one of the horses, his shoulders screwed under the scanty folds of an oil-cloth cape, and his knees drawn nearly up to the pommel of the saddle, to avoid the thumping bushes and briers that occasionally assailed him, as the team plunged along in a stumbling pace. Their pathway, or rather their direction, for there was no beaten road, lay along the northern bank of the “Mad Missouri,” some two hundred miles above the St. Louis settlement. It was at a time when there were no white men in those regions save a few trappers, traders, and emigrants, and each new sojourner found it convenient to carry with him a means of shelter, as houses of any description were but few and far between.

Our travellers had been told in the morning, when setting out from a temporary village which consisted of a few families of emigrants, with whom they had sojourned the preceding night, that they could attain the desired point by making the river their guide, should they be at a loss to distinguish the faintly-marked pathway that led in a more direct course to the place of destination. The storm coming up suddenly from the north, and showers of hail accompanying the gusts, caused the poor driver to incline his face to the left, to avoid the peltings that assailed him so frequently; and the drenched horses, similarly influenced, had unconsciously departed far from the right line of march; and now, rather than turn his front again to the pitiless blast, which could be the only means of regaining the road, Joe preferred diverging still farther, until he should find himself on the margin of the river, by which time he hoped the storm would abate. At all events, he thought there would be more safety on the beach, which extended out a hundred paces from the water, among the small switches of cotton-wood that grew thereon, than in the midst of the tall trees of the forest, where a heavy branch was every now and then torn off by the wind, and thrown to the earth with a terrible crash. Occasionally a deafening explosion of thunder would burst overhead; and Joe, prostrating himself on the neck of his horse, would, with his eyes closed and his teeth set, bear it out in silence. He spoke not, save to give an occasional word of command to his team, or a brief reply to a question from his master.

It was an odd spectacle to see such a vehicle trudging along at such an hour, where no carriage had ever passed before. The two young men were odd characters; the horses were oddly matched, one being a little dumpy black pony, and the other a noble white steed; and it was an odd whim which induced Glenn to abandon his comfortable home in Philadelphia, and traverse such inclement wilds. But love can play the “wild” with any young man. Yet we will not spoil our narrative by introducing any of it here. Nor could it have been love that induced Joe to share his master’s freaks; but rather a rare penchant for the miraculous adventures to be enjoyed in the western wilderness, and the gold which his master often showered upon him with a reckless hand. Joe’s forefathers were from the Isle of Erin, and although he had lost the brogue, he still retained some of their superstitions.

The wind continued to blow, the wolves howled, the lightning flashed, and the thunder rolled. Ere long the little black pony snorted aloud and paused abruptly.

“What ails you, Pete?” said Joe from his lofty position on the steed, addressing his favourite little pet. “Get along,” he continued, striking the animal gently with his whip. But Pete was as immovable and unconscious of the lash as would have been a stone. And the steed seemed likewise to be infected with the pony’s stubbornness, after the wagon was brought to a pause.

“Why have you stopped, Joe?” inquired Glen.

“I don’t hardly know, sir; but the stupid horses won’t budge an inch farther!”

“Very well; we can remain here till morning. Take the harness off, and give them the corn in the box; we can sleep in the wagon till daylight.”

“But we have no food for ourselves, sir; and I’m vastly hungry. It can’t be much farther to the ferry,” continued Joe, vexed at the conduct of the horses.

“Very well; do as you like; drive on, if you desire to do so,” said Glenn.

“Get along, you stupid creatures!” cried Joe, applying the lash with some violence. But the horses regarded him no more than blocks would have done. Immediately in front he perceived a dark object that resembled a stump and turning the horses slightly to one side, endeavoured to urge them past it. Still they would not go, but continued to regard the object mentioned with dread, which was manifested by sundry restless pawings and unaccustomed snorts. Joe resolved to ascertain the cause of their alarm, and springing to the ground, moved cautiously in the direction of the dark obstruction, which still seemed to be a blackened stump, about his own height, and a very trifling obstacle, in his opinion, to arrest the progress of his redoubtable team. The darkness was intense, yet he managed to keep his eyes on the dim outlines of the object as he stealthily approached And he stepped as noiselessly as possible, notwithstanding he meditated an encounter with nothing more than an inanimate object. But his imagination was always on the alert, and as he often feared dangers that arose undefinable and indescribable in his mind, it was not without some trepidation that he had separated himself from the horses and groped his way toward the object that had so much terrified his pony. He paused within a few feet of the object, and waited for the next flash of lightning to scrutinize the thing more closely before putting his hand upon it. But no flash came, and he grew tired of standing. He stooped down, so as to bring the upper portion of it in a line with the sky beyond, but still he could not make it out. He ventured still nearer, and stared at it long and steadily, but to no avail: the black mass only was before him, seemingly inanimate, and of a deeper hue than the darkness around.

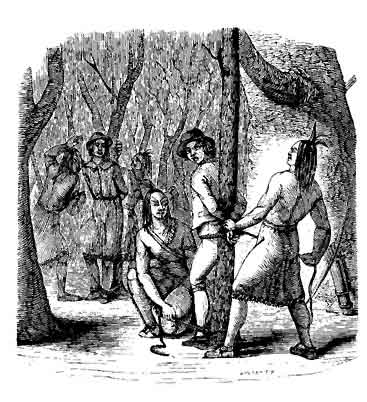

A dark encounter.

“I’ve a notion to try my whip on you,” said he, thinking if it should be a human being it would doubtless make a movement. He started back with a momentary conviction that he heard a rush creak under its feet. But as it still maintained its position, he soon concluded the noise to have been only imaginary, and venturing quite close gave it a smart blow with his whip. Instantaneously poor Joe was rolling on the earth, almost insensible, and the dark object disappeared rushing through the bushes into the woods. The noise attracted Glenn, who now approached the scene, and with no little surprise found his servant lying on his face.

“What’s the matter, Joe?” demanded he.

“Oh, St. Peter! O preserve me!” exclaimed Joe.

“What has happened? Why do you lie there?”

“Oh, I’m almost killed! Didn’t you see him?”

“See what? I can see nothing this dark night but the flying clouds and yonder yellow sheet of water.”

“Oh, I’ve been struck!” said Joe, groaning piteously.

“Struck by what? Has the lightning struck you?”

“No—no! my head is all smashed up—it was a bear.”

“Pshaw! get up, and either drive on, or feed the horses,” said Glenn with some impatience.

“I call all the saints to witness that it was a wild bear—a great wild bear! I thought it was a stump, but just as I struck it a flash of lightning revealed to my eyes a big black bear standing on his hind feet, grinning at me, and he gave me a blow on the side of the face, which has entirely blinded my left eye, and set my ears to ringing like a thousand bells. Just feel the blood on my face.”

Glenn actually felt something which might be blood, and really had thought he could distinguish the stump himself when the wagon halted; yet he did not believe that Joe had received the hurt in any other manner than by striking his face against some hard substance which he could not avoid in the darkness.

“You only fancy it was a bear, Joe; so come along back to the horses and drive on. The rain has ceased, and the stars are appearing.” Saying this, Glenn led the way to the wagon.

“I’d be willing to swear on the altar that it was a huge bear, and nothing else!” replied Joe, as he mounted and drove on, the horses now evincing no reluctance to proceed. One after another the stars came out and shone in purest brightness as the mists swept away, and ere long the whole canopy of blue was gemmed with twinkling brilliants. The winds soon lulled, and the dense forest on the right reposed from the moaning gale which had disturbed it a short time before; and the waves that had been tossed into foaming ridges now spent their fury on the beach, each lashing the bank more gently than the last, until the power of the gliding current swept them all down the turbid stream. Soon the space between the water and the forest gradually diminished, and seemed to join at a point not far ahead. Joe observed this with some concern, being aware that to meander among the trees at such an hour was impossible. He therefore inclined toward the river, resolved to defer his re-entrance into the forest as long as possible. As he drove on he kept up a continual groaning, with his head hung to one side, as if suffering with the toothache, and occasionally reproaching Pete with some petulance, as if a portion of the blame attached to his sagacious pony.

“Why do you keep up such a howling, Joe? Do you really suffer much pain?” inquired Glenn, annoyed by his man’s lamentations.

“It don’t hurt as bad as it did—but then to think that I was such a fool as to go right into the beast’s clutches, when even Pete had more sense!”

“If it was actually a bear, Joe, you can boast of the thrilling encounter hereafter,” said Glenn, in a joking and partly consoling manner.

“But if I have many more such, I fear I shall never get back to relate them. My face is all swelled—Huzza! yonder is a light, at last! It’s on this side of the river, and if we can’t get over the ferry to-night, we shall have something to eat on this side, at all events. Ha! ha! ha! I see a living man moving before the fire, as if he were roasting meat.” Joe forgot his wound in the joy of an anticipated supper, and whipping the horses into a brisk pace, they soon drew near the encampment, where they discovered numerous persons, male and female, who had been prevented from crossing the river that day, in consequence of the violence of the storm, and had raised their tents at the edge of the woods, preferring to repose thus until the following morning than to venture into the frail ferry-boat while the waves yet ran so high.

There was no habitation in the immediate vicinity, save a rude hovel occupied by Jasper Roughgrove and his ferrymen, which was on the opposite shore in a narrow valley that cleft asunder the otherwise uniform cliff of rocks.

The creaking of the wheels, when the vehicle approached within a few hundred paces of the encampment, attracted the watch-dogs, and their fierce and continued barking drew the attention of the emigrants in the direction indicated. Several men with guns in their hands came out to meet the young travellers.

“We are white men, friends, strangers, lost, benighted, and hungry!” exclaimed Joe, stopping the horses, and addressing the men before he was accosted.

“Come on, then, and eat and rest with us,” said they, amused at Joe’s exclamations, and leading the way to the encampment.

When they arrived at the edge of the camp, Glenn dismounted from the wagon, and directing Joe to follow when he had taken care of the horses, drew near the huge log fire in company with those who had gone out to meet him. Several tall and spreading elms towered in majesty above, and their clustering leaves, yet partially green, notwithstanding the autumn was midway advanced, were beautifully tinged by the bright light thrown upward from the glaring flames. The view on one side was lost in the dark labyrinth of the moss-grown trunks of the forest. On the other swept the turbid river, bearing downward in its rapid current severed branches, and even whole trees, that had been swept away by the continual falling in of the river bank, for the sandy soil was always subject to the undermining of tho impetuous stream. A circle of tents was formed round the fire, constructed of thin poles bent in the shape of an arch, and the ends planted firmly in the earth. These were covered with buffalo skins, which would effectually shield the inmates from the rain; and quantities of leaves, after being carefully dried before the fire, were placed on the ground within, over which were spread buffalo robes with the hair uppermost, and thus in a brief space was completed temporary but not uncomfortable places of repose. The ends of the tents nearest to the fire were open, to admit the heat and a portion of light, that those who desired it might retire during their repast, or engage in pious meditation undisturbed by the more clamorous portion of the company.

Glenn paused when within the circle, and looked with some degree of interest on the admirable arrangement of those independent and hardy people. A majority of the emigrants were seated on logs brought thither for that purpose, and feasting quietly from several large pans and well-filled camp-kettles, which were set out for all in common. They motioned Glenn to partake with them; and although many curious looks were directed toward him, yet he was not annoyed by questions while eating. Joe came in, and following the example of the rest, played his part to perfection, without complaining once of his wound.

The feast was just finished, when the dogs again set up a furious yelping, and ran into the forest. But they returned very quickly, some of them whining with the hurts received from the strangers they encountered so roughly; and presently they were followed by several enormous hounds, and soon after an athletic woodsman was seen approaching. This personage was a tall muscular man, past the middle age, but agile and vigorous in all his motions. He was habited in a buck-skin hunting-shirt, and wore leggins of the same material. Although he was armed with a long knife and heavy rifle, and the expression of his brow and chin indicated an unusual degree of firmness and determination, yet there was an openness and blandness in the expression of his features which won the confidence of the beholder, and instantly dispelled every apprehension of violence. All of the emigrants had either seen or heard of him before, for his name was not only repeated by every tongue in the territory, but was familiar in every State in the Union, and not unknown in many parts of Europe. He was instantly recognised by the emigrants, and crowding round, they gave him a hearty welcome. They led him to a conspicuous seat, and forming a circle about him, were eager to catch every word that might escape his lips, and relied with implicit confidence on every species of information he imparted respecting the dangers and advantages of the locations they were about to visit. Boone had settled some three miles distant from the ferry, among the hills, where his people were engaged in the manufacture of salt. He had selected this place of abode long before the general tide of emigration had reached so far up the Missouri. It was said that he pitched his tent among the barren hills as a security against the intrusion of other men, who, being swayed by a love of wealth, would naturally seek their homes in the rich level prairies. It is true that Boone loved to dwell in solitude. But he was no misanthrope. And now, although questions were asked without number, he answered them with cheerfulness; advised the families what would be necessary to be done when their locations were selected, and even pressingly invited them to remain in his settlement a few days to recover from the fatigue of travel, and promised to accompany them afterward over the river into the rich plains to which they were journeying.

During the brisk conversation that had been kept up for a great length of time, Glenn, unlike the rest of the company, sat at a distance and maintained a strict silence. Occasionally, as some of the extraordinary feats related of the person before him occurred to his memory, he turned his eyes in the direction of the great pioneer, and at each time observed the gaze of the woodsman fixed upon him. Nevertheless his habitual listlessness was not disturbed, and he pursued his peculiar train of reflections. Joe likewise treated the presence of the renowned Indian fighter with apparent unconcern, and being alone in his glory, dived the deeper into the saucepan.

Boone at length advanced to where Glenn was sitting, and after scanning his pale features, and his costly though not exquisitely-fashioned habiliments, thus addressed him:—

“Young man, may I inquire what brings thee to these wilds?”

“I am a freeman,” replied Glenn, somewhat haughtily, “and may be influenced by that which brings other men hither.”

“Nay, young man, excuse the freedom which all expect to exercise in this comparative wilderness; but I am very sure there is not another emigrant on this side of the Ohio who has been actuated by the same motives that brought thee hither. Others come to fell the forest oak, and till the soil of the prairie, that they may prepare a heritage for their children; but thy soft hands and slender limbs are unequal to the task; nor dost thou seem to have felt the want of this world’s goods; and thou bringest no family to provide for. Thou hast committed that which banished thee from society, or found in society that which disgusted thee—speak, which of these?” said Boone, in accents, though not positively commanding, yet they produced a sense of reverence that subdued the rising indignation of Glenn, and looking upon the interrogator as the acknowledged host of the eternal wilds, and himself as a mere guest, who might be required to produce his testimonials of worthiness to associate with nature’s most honest of men, he replied with calmness, though with subdued emotion—

“You are right, sir—it was the latter. I had heard that you were happy in the solitude of the mountain-shaded valley, or on the interminable prairies that greet the horizon in the distance, where neither the derision of the proud, the malice of the envious, nor the deceptions of pretended love and friendship, could disturb your peaceful meditations: and from amid the wreck of certain hopes, which I once thought no circumstances could destroy, I rose with a determined though saddened heart, and solemnly vowed to seek such a wilderness, where I could pass a certain number of my days engaging in the pursuits that might be most congenial to my disposition. Already I imagine I experience the happy effects of my resolution. Here the whispers of vituperating foes cannot injure, nor the smiles of those fondly cherished deceive.”

“Your hand, young man,” said Boone, with an earnestness which convinced Glenn that his tale was not imprudently divulged.

“Ho! what’s the matter with you?” Boone continued, turning to Joe, who had just arisen from his supper, and was stretching back his shoulders.

“I got a licking from a bear to-night—but I don’t mind it much since I’ve had a snack. But if ever I come across him in the daytime, I’ll show him a thing or two,” said Joe, with his fists doubled up.

“Pshaw! do you still entertain the ridiculous belief that it was really a bear you encountered?” inquired Glenn, with an incredulous smile.

“I’ll swear to it!” replied Joe.

“Let me see your face,” remarked Boone, turning him to where there was more light.

“Hollo! don’t squeeze it so hard!” cried Joe, as Boone removed some of the coagulated blood that remained or the surface.

“There is no doubt about it—it was a bear, most certainly,” said Boone; and examining the wound more closely, continued: “Here are the marks of his claws, plain enough: he might easily be captured to-morrow. Who will hunt him with me?”

“I will!” burst from the lips of nearly every one present.

“Huzza—revenge! I’ll have revenge, huzza!” cried Joe, throwing round his hat.

“You will join us?” inquired Boone, turning to Glenn.

“Yes,” replied Glenn; “I came hither provided with the implements to hunt; and as such is to be principally my occupation during my sojourn in this region, I could not desire a more happy opportunity than the present to make a beginning. And as it is my intention to settle near the ferry on the opposite shore, I am pleased to find that I shall not be far from one whose acquaintance I hoped to make, above all others.”

“And you may not find me reluctant to cultivate a social intercourse, notwithstanding men think me a crabbed old misanthrope,” replied Boone, pressing the extended hand of Glenn. They then separated for the night, retiring to the tents that had been provided for them.

It was not long before a comparative silence pervaded the scene. The fierce yelpings of the watch-dogs gradually ceased, and the howling wolf was but indistinctly heard in the distance. The katydid and whippoorwill still sang at intervals, and these sounds, as well as the occasional whirlpool that could be heard rising on the surface of the gliding stream, had a soothing influence, and lulled to slumber the wandering mortals who now reclined under the forest trees, far from the homes of their childhood and the graves of their kindred. Glenn gazed from his couch through the branches above at the calm, blue sky, resplendent with twinkling stars; and if a sad reflection, that he thus lay, a lonely being, a thousand miles from those who had been most dear to him, dimmed his eye for an instant with a tear, he still felt a consciousness of innocence within, and resolving to execute his vow in every particular, he too was soon steeped in undisturbed slumber.

Boone hunts the bear—Hounds and terriers—Sneak Punk, the Hatchet-face—Another stump—The high passes—The bear roused—The chase—A sight—A shot—A wound—Joe—His meditations—His friend, the bear—The bear retreats—Joe takes courage—He fires—Immense execution—Sneak—The last struggle—Desperation of the bear—His death—Sneak’s puppies—Joe.

By the time the first streaks of gray twilight marked the eastern horizon, Boone, at the head of the party of hunters, set out from the encampment and proceeded down the river in the direction of the place where Joe had been so roughly handled by Bruin. All, with the exception of Glenn and his man, being accustomed to much walking, were on foot. Glenn rode his white steed, and Joe was mounted on his little black pony. The large hounds belonging to Boone, and the curs, spaniels, and terriers of the emigrants were all taken along. As they proceeded down the river, Boone proposed the plan of operations which was to guide their conduct in the chase, and each man was eager to perform his part, whatever it might be. It was arranged that a portion of the company should precede the rest, and cross the level woodland about two miles in width, to a range of hills and perpendicular cliffs that appeared to have once bounded the river, and select such ravines or outlets as in their opinion the bear would be most likely to pass through, if he were indeed still in the flat bottom-land. At these places they were to station themselves with their guns well charged, and either await the coming of the animal or the drivers; the first would be announced by the yelping of the dogs, and the last by the hunters’ horns.

Glenn and one or two others remained with Boone to hunt Bruin in his lair, while Joe and the remainder of the company were despatched to the passes among the hills. There was a narrow-featured Vermonter in this party, termed, by his comrades, the Hatchet-face, and, in truth, the extreme thinness of his chest and the slenderness of his limbs might as aptly have been called the hatchet-handle. But, so far from being unfit for the hardy pursuits of a hunter, he was gifted with the activity of a greyhound, and the swiftness and bottom of a race-horse. His name was Sneak Punk, which was always abbreviated to merely Sneak, for his general success in creeping up to the unsuspecting game of whatsoever kind he might be hunting, while others could not meet with such success. He had been striding along some time in silence a short distance in advance of Joe, who, even by dint of sundry kicks and the free use of his whip, could hardly keep pace with him. The rest were a few yards in the rear, and all had maintained a strict silence, implicitly relying on the guidance of Sneak, who, though he had never traversed these woods before, was made perfectly familiar with the course he was to pursue by the instructions of Boone.

Although the light of morning was now apparent above, yet the thick growth of the trees, whose clustering branches mingled in one dense mass overhead, made it still dark and sombre below; and Joe, to divert Sneak from his unconscionable gait, which, in his endeavours to keep up, often subjected him to the rude blows of elastic switches, and many twinges of overhanging grape vines, essayed to engage his companion in conversation.

“I say, Mr. Sneak,” observed Joe, with an eager voice, as his pony trotted along rather roughly through the wild gooseberry bushes, and often stumbled over the decayed logs that lay about.

“What do you want, stranger?” replied Sneak, slackening his gait until he fell back alongside of Joe.

“I only wanted to know if you ever killed a bear before,” said Joe, drawing an easy breath as Pete fell into a comfortable walk.

“Dod rot it, I hain’t killed this one yit,” said Sneak.

“I didn’t mean any offence,” said Joe.

“What makes you think you have given any?”

“Because you said dod rot it.”

“I nearly always say so—I’ve said so so often that I can’t help it. But now, as we are on the right footing, I can tell you that I wintered once in Arkansaw, and that’s enough to let you know I’m no greenhorn, no how you can fix it. And moreover, I tell you, if old Boone wasn’t here hisself, I’d kill this bar as sure as a gun, and my gun is as sure as a streak of lightning run into a barrel of gunpowder;” and as he spoke he threw up his heavy gun and saluted the iron with his lips.

“Is your’s a rifle?” inquired Joe, to prolong the conversation, his companion showing symptoms of a disposition to fall into his habit of going ahead again.

“Sartainly! Does anybody, I wonder, expect to do any thing with a shot-gun in sich a place as this?”

“Mine’s a shot-gun,” said Joe.

“Dod—did you ever kill any thing better than a quail with it?” inquired Sneak, contemptuously.

“I never killed any thing in my life with it—I never shot a gun in all my life before to-night,” said Joe.

“Dod, you haven’t fired it to-night, to my sartain knowledge.”

“I mean I never went a shooting.”

“Did you load her yourself?” inquired Sneak, taking hold of the musket and feeling the calibre.

“Yes—but I’m sure I did it right. I put in a handful of powder, and paper on top of it, and then poured in a handful of balls,” said Joe.

“Ha! ha! ha! I’ll be busted if you don’t raise a fuss if you ever get a shot at the bar!” said Sneak, with emphasis.

“That’s what I am after.”

“Why don’t you go ahead?” demanded Sneak, as Joe’s pony stopped suddenly, with his ears thrust forward. “Dod! whip him up,” continued he, seeing that his companion was intently gazing at some object ahead, and exhibiting as many marks of alarm as Pete. “It’s nothing but a stump!” said Sneak, going forwards and kicking the object, which was truly nothing more than he took it to be. Joe then related to him all the particulars of his nocturnal affair with the supposed stump, previous to his arrival at the camp, and Sneak, with a hearty laugh, admitted that both he and the pony were excusable for inspecting all the stumps they might chance to come across in the dark in future. They now emerged into the open space which was the boundary of the woods, and after clambering up a steep ascent for some minutes, they reached the summit of a tall range of bluffs. From this position the sun could be seen rising over the eastern ridges, but the flat woods that had been traversed still lay in darkness below, and silent as the tomb, save the hooting of owls as they flapped to their hollow habitations in the trees.

The party then dispersed to their coverts under the direction of Sneak, who with a practised eye instantly perceived all the advantageous posts for the men, and the places where the bear would most probably run. Joe had insisted on having his revenge, and begged to be stationed where he would be most likely to get a shot. He was therefore permitted to remain at the head of the ravine they had just ascended, through which a deer path ran, as the most favourable position. After tying Pete some paces in the rear, he came forwards to the verge of the valley and seated himself on a dry rock, where he could see some distance down the path under the tall sumach bushes. He then commenced cogitating how he would act, should Bruin have the hardihood to face him in the daytime.

Boone and his party drew near the spot where the bear had been seen the previous night. The two large hounds, Ringwood and Jowler, kept at their master’s heels, being trained to understand and perform all the duties required of them, while the curs and terriers were running helter-skelter far ahead, or striking out into the woods without aim, and always returning without effecting any thing. At length the two hounds paused, and scented the earth, giving certain information that they had arrived at the desired point. The curs and terriers had already passed far beyond the spot, being unable to decide any thing by the nose, and always relying on their swiftness in the chase when they should be in sight of the object pursued.

Now, Glenn perceived to what perfection dogs could be trained, and learned, what had been a matter of wonder to him, how Boone could keep up with them in the chase. The hounds set off at a signal from their master, not like an arrow from the bow, but at a moderate pace, ever and anon looking back and pausing until the men came up; while the erratic curs flew hither and thither, chasing every hare and squirrel they could find. As they pursued the trail they occasionally saw the foot-print of the animal, which was broad and deep, indicating one of enormous size. Presently they came to a spot thickly overgrown with spice-wood bushes and prickly vines, where he had made his lair, and from the erect tails of Ringwood and Jowler, and the intense interest they otherwise evinced, it was evident they were fast approaching the presence of Bruin. Ere long, as they ran along with their heads up, for the first time that morning, they commenced yelping in clear and distinct tones, which rang musically far and wide through the woods. The curs relinquished their unprofitable racing round the thickets, attracted by the hounds, and soon learned to keep in the rear, depending on the unerring trailing of the old hunters, as the object of pursuit was not yet in sight. The chase became more animated, and the men quickened their pace as the inspiring notes of the hounds rang out at regular intervals. Glenn soon found he possessed no advantage over those on foot, who were able to run under the branches of the trees, and glide through the thickets with but little difficulty, while the rush of his noble steed was often arrested by the tenacious vines clinging to the bushes abreast, and he was sometimes under the necessity of dismounting to recover his cap or whip.

It was not long before the notes of Ringwood and Jowler suddenly increased in sharpness and quickness, and the curs and terriers, hitherto silent, set up a confused medley of sounds, which reverberated like one continuous scream. They had pounced upon the bear, and from the stationary position of the dogs for a few minutes, indicated by their peculiar baying, it was evident Bruin had turned to survey the enemy, and perhaps to give them battle; but it seemed that their number or noise soon intimidated him, and that he preferred seeking safety in flight. How Boone could possibly know beforehand which way the bear would run, was a mystery to Glenn; but that he often abandoned the direction taken by the dogs, turning off at almost right angles, and still had a sight of him was no less true. No one had yet been near enough to fire with effect. The bear, notwithstanding his many feints and novel demonstrations to get rid of his persecutors, had continued to make towards the hills where the standers were stationed. Boone falling in with Glenn, from whom he had been frequently separated, they continued together some time, following the course of the sounds towards the east.

“This sport is really exciting and noble!” exclaimed Glenn, as the deep and melodious intonations of Ringwood and Jowler fell upon his ear.

“Excellent! excellent!” replied Boone, listening intently, and pausing suddenly, as the discharge of a gun in the direction of the hills sounded through the woods.

“He has reached the standers,” remarked Glenn, reining up his steed at Boone’s side.

“No; it was one of our men who has not followed him in all his deviations,” replied Boone, still marking the notes of the hounds.

“I doubt not our company is sufficiently scattered in every direction through the forest to force him into the hills very speedily, if, indeed, that shot was not fatal,” remarked Glenn.

“He is not hurt—perhaps it was not fired at him, but at a bird—nor will he yet leave the woods,” said Boone, still listening to the hounds. “He comes!” he exclaimed a moment after, with marks of joy in his face; “he will make a grand circle before quitting the lowland.” And now the dogs could be heard more distinctly, as if they were gradually approaching the place from which they first started.

“If you will remain here,” continued Boone, “it is quite likely you will have a shot as he makes his final push for the hills.”

“Then here will I remain,” replied Glenn; and fixing himself firmly in the saddle, resolved to await the coming of Bruin, having every confidence in the intimation of his friend. Boone selected a position a few hundred paces distant, with a view of permitting Glenn to have the first fire.

The bear took a wide circuit towards the river, pausing at times until the foremost of the dogs came up, which he could easily manage to keep at bay; but when all of them (and the curs did good service now) surrounded him, he found it necessary to set forward again. When he had run as far as the river, and turned once more towards the hills, his course seemed to be in a direct line with Glenn, and the young man’s heart fluttered with anticipation as he examined his gun, and turned his horse (which had been accustomed to firearms) in a favourable position to give the enemy a salute as he passed. Nearer they came, the dogs pursuing with redoubled fierceness, their blood heated by the exercise, and their most sanguine passions roused by their frequent severe skirmishes with their huge antagonist. As they approached, the strange and simultaneous yelpings of the curs and terriers resembled an embodied roar, amid which the flute-like notes of Ringwood and Jowler could hardly be heard. Glenn could now distinctly hear the bear rushing like a torrent through the bushes, almost directly towards the place where he was posted, and a moment after it emerged from a dense thicket of hazel, and the noble steed, instead of leaping away with affright, threw back his ears and stood firm, until Glenn fired. Bruin uttered a howl, and halting with a fierce growl, raised himself on his haunches, and displaying his array of white teeth, prepared to assail our hero. Glenn proceeded to reload his rifle with as much expedition as was in his power, though not without some tremor, notwithstanding he was mounted on his tall steed, whose nostrils dilated, and eyes flashing fire, indicated that he was willing to take part in the conflict. The bear was preparing for a dreadful encounter, and on the very eve of springing towards his assailant, when the hounds coming up admonished him to flee his more numerous foes, and turning off, he continued his route towards the hills. Glenn perceived that he had not missed his aim by the blood sprinkled on the bushes, and being ready for another fire, galloped after him. Just when he came in sight, Boone’s gun was heard, and Bruin fell, remaining motionless for a moment; but ere Glenn arrived within shooting distance, or Boone could reload, he had risen and again continued his course, as if in defiance of everything that man could do to oppose him.

“Is it possible he still survives!” exclaimed Glenn, joining his companion.

“There is nothing more possible,” replied Boone; “but I saw by his limping that your shot had taken effect.”

“And I saw him fall when you fired,” said Glenn; “but he still runs.”

“And he will run for some time yet,” remarked Boone, “for they are extremely hard to kill, when heated by the pursuit of dogs. But we have done our part, and it now remains for those at the passes to finish the work so well begun.”

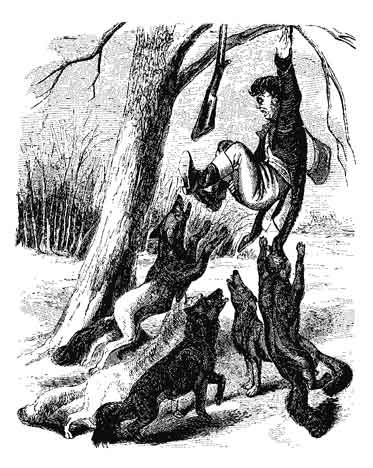

Joe’s imagination had several times worked him into a fury, which had as often subsided in disappointment, during the chase below, every particle of which could be distinctly heard from his position. More than once, when a brisk breeze swept up the valley, he was convinced that his enemy was approaching him, and, every nerve quivering with the expectation of the bear coming in view the next instant, he stood a spectacle of eagerness, with perhaps a small portion of apprehension intermingled. At length, from the frequent deceptions the distance practiced upon him, he grew composed by degrees, and resuming his seat on the stone, with his musket lying across his knees, thus gave vent to his thoughts: “What if an Indian were to pounce upon me while I’m sitting here?” Here he paused, and looked carefully round in every direction. “No!” he continued; “if there were any at this time in the neighbourhood, wouldn’t Boone know it? To be sure he would, and here’s my gun—I forgot that. Let them come as soon as they please! I wonder if the bear will come out here? Suppose he does, what’s the danger? Didn’t I grapple with him last night? And couldn’t I jump on Pete and get away from him! But—pshaw! I keep forgetting my gun—I wish he would come, I’d serve him worse than he served me last night! My face feels very sore this morning. There!” he exclaimed, when he heard the fire of Glenn’s gun, and the report that succeeded from Boone’s, “they’ve floored him as dead as a nail, I’ll bet. Hang it! I should like to have had a word or two with him myself, to have told him I hadn’t forgotten his ugly grin. The men must have known I would stand no chance of killing him when they placed me up here. I should like to know what part of the sport I’ve had—ough!” exclaimed he, his hair standing upright, as he beheld the huge bear, panting and bleeding, coming towards him, and not twenty paces distant!

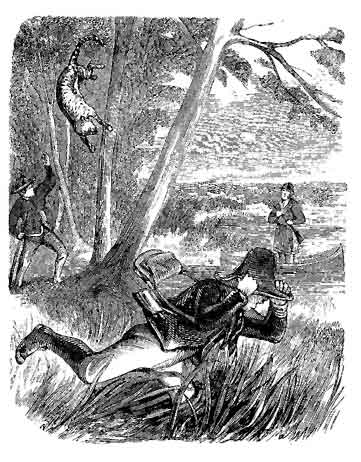

Bruin had eluded the dogs a few minutes by climbing a bending tree at the mouth of the valley, from which he passed to another, and descending again to the earth, proceeded almost exhausted up the ravine. Joe’s eyes grew larger and larger as the monster approached, and when within a few feet of him he uttered a horrible unearthly sound, which attracted the bear, and fearing the fatal aim of man more than the teeth of the dogs, he whirled about, with a determination to fight his way back, in preference to again risking the murderous lead. No sooner was the bear out of sight, and plunging down the dell amid the cries of the dogs, which assailed him on all sides, than Joe bethought him of his gun, and becoming valorous, ran a few steps down the path and fired in the direction of the confused melée. The moment after he discharged his musket, the back part of his head struck the earth, and the gun made two or three end-over-end revolutions up the path behind him. Never, perhaps, was such a rebound from overloading known before. Joe now thought not of the bear, nor looked to see what execution he had done. He thought of his own person, which he found prostrate on the ground. When somewhat recovered from the blow, he rose with his hand pressed to his nose, while the blood ran out between his fingers. “Oh! my goodness!” he exclaimed, seating himself at the root of a pecan tree, and rocking backwards and forwards.

“What’s your gun doing up here?” exclaimed Sneak, coming down the path. Joe made no answer, but continued to rock backwards and forwards most dolefully.

“Why don’t you speak? Where’s the bar?”

“I don’t know. Oh!” murmured Joe.

“What’s the matter?” inquired Sneak, seeing the copious effusion of blood.

“I shot off that outrageous musket, and it’s kicked my nose to pieces! I shall faint!” said Joe, dropping his head between his knees.

“Faint? I never saw a man faint!” said Sneak, listening to the chase below.

“Oh! can’t you help me to stop this blood?”

“Don’t you hear that, down there?” replied Sneak, his attention entirely directed to that which was going on in the valley.

“My ears are deafened by that savage gun! I can’t hear a bit, hardly! Oh, what shall I do, Mr. Sneak?” continued Joe.

“Dod rot it!” exclaimed Sneak, leaping like a wild buck down the path, and paying no further attention to the piteous lamentations of his comrade.

Ere the bear reached the mouth of the glen, the hunters generally had come up, and poor Bruin found himself hemmed in on all sides. He could not ascend on either hand, the loss of blood having weakened him too much to climb over the almost precipitous rocks, and he made a final stand, determined to sell his life as dearly as possible. The dogs sprang upon him in a body, and it was soon evident that his desperate struggles were not harmless. He grasped one of the curs in his deadly hug, and with his teeth planted in its neck, relinquished not his hold until it fell from his arms a disfigured and lifeless object. He boxed those that were tearing his hams with his ponderous claws, sending them screaming to the right and left. He then stood up on his haunches, with his back against a rock, and with a snarl of defiance resolved never to retreat “from its firm base.” Never were blows more rabidly dealt. When attacked on one side, he had no sooner turned to beat down his sanguine foe than he was assailed on the other. Thus he fought alternately from right to left, his mouth gaping open, his tongue hanging out, and his eyes gleaming furiously as if swimming in liquid fire. At times he was charged simultaneously in front and flank, when for an instant the whole group seemed to be one dark writhing mass, uttering a medly of discordant and horrid sounds. But determined to conquer or die on the spot he occupied, Bruin never relaxed his blows, until the bruised and exhausted dogs were forced to withdraw a moment the combat, and rush into the narrow rivulet. While they lay panting in the water, the bear turned his head back against the rocks, and lapped in the dripping moisture without moving from his position. But he was fast sinking under his wounds: a stream of blood, which constantly issued from his body and ran down and discoloured the water, indicated that his career was nearly finished. Yet his spirit was not daunted; for while the canine assailants he had withstood so often were bathing preparatory for a renewal of the conflict, Boone and Glenn, who had approached the immediate vicinity, fired, and Bruin, echoing the howl of death as the bullets entered his body, turned his eyes reproachfully towards the men for an instant, and then, with a growl of convulsed, expiring rage, plunged into the water, and, seizing the largest cur, crushed him to death. Ringwood and Jowler, whose sagacity had hitherto led them to keep in some measure aloof, knowing their efforts would be unavailing against so powerful an enemy without the fatal aim of their master, now sprang forward to the rescue, both seizing the prostrate foe by the throat. But he could not be made to relinquish his victim, nor did he make resistance. Boone, advancing at the head of the hunters, (all of whom, with the exception of Joe and Sneak, being there assembled,) with some difficulty prevented his companions from discharging their guns at the dark mass before them. He struck up several of their guns as they were endeavouring to aim at the now motionless bear, fearing that his hounds might suffer by their fire, and stooping down, whence he could distinctly see the pale gums and tongue, as his hounds grappled the neck of the animal, announced the death of Bruin, and the termination of the hunt. The hounds soon abandoned their inanimate victim, and its sinewy limbs relaxing, the devoted cur rolled out a lifeless body.

“How like you this specimen of our wild sports?” inquired Boone, turning to Glenn, as the rest proceeded to skin and dress the bear preparatory for its conveyance to the camp.

“It is exciting, if not terrific and cruel,” replied Glenn, musing.

“None could be more eager than yourself in the chase,’ said Boone.

“True,” replied Glenn; “and notwithstanding the uninitiated may for an instant revolt at the spilling of blood, yet the chase has ever been considered the noblest and the most innocent of sports. The animals hunted are often an evil while running at large, being destructive or dangerous; but even if they were harmless in their nature, they are still necessary or desirable for the support or comfort of man. Blood of a similar value is spilt everywhere without the least compunction. The knife daily pierces the neck of the swine, and the kitchen wench wrings off the head of the fowl while she hums a ditty. This is far better than hunting down our own species on the battle-field, or ruining and being ruined at the gaming-table. I think I shall be content in this region.”

“And you will no doubt be an expert hunter, if I have any judgment in such matters,” replied Boone.

“I wonder that Joe has not yet made his appearance,” remarked Glenn, approaching the bear; “I expected ere this to have seen him triumphing over his fallen enemy.”

“What kind of a gun had he?” inquired Boone.

“A large musket,” said Glenn, recollecting the enormous explosion that seemed to jar the whole woods like an earthquake; “it must have been Joe who fired—he had certainly overcharged the gun, and I fear it has burst in his hands, which may account for his absence.”

“Be not uneasy,” replied Boone; “for I can assure you from the peculiar sound it made that it did nothing more than rebound violently; besides, those guns very rarely burst. But here comes Sneak, (I think they call him so,) no doubt having some tidings of your man. It seems he has not been idle. He has a brace of racoons in his hands.”

The tall slim form of Sneak was seen coming down the path. Ever and anon he cast his eyes from one hand to the other, regarding with no ordinary interest the dead animals he bore.

“I did not hear him fire,” remarked Glenn.

“He may have killed them with stones,” said Boone; and as Sneak drew near, he continued, with a smile, “they are nothing more than a brace of his terriers, that doubtless Bruin dispatched, and which may well be spared, notwithstanding Sneak’s seeming sorrow.”

Sneak approached the place where Boone and Glenn were standing, with the gravest face that man ever wore. His eyes seemed to be set in his head, for not once did they wink, nor did his lips move for some length of time after he threw down the dogs at the feet of Glenn, although several men addressed him. He stood with his arms folded, and gazed mournfully at his dead dogs.

“The little fellows fought bravely, and covered themselves with glory,” said Glenn, much amused at the solemn demeanour of Sneak.

“If there ain’t more blood spilt on the strength of it, I wish I may be smashed!” said Sneak, compressing his lips.

“What mean you? what’s the matter?” inquired Boone, who best understood what the man was meditating.

“I’ve got as good a gun as anybody here! And I’ll have revenge, or pay!” replied Sneak, turning his eyes on Glenn.

“If your remarks are intended for me,” said Glenn, “rely upon it you shall have justice.”

“Tell us all about it,” said Boone.

“When I heard that fool up the valley shoot off his forty-four pounder, I ran to see what he had done, and when I came near to where he was, his gun was lying up the hill behind him, and he setting down whining like a baby, and a great gore of blood hanging to his nose. I wish it had blowed his head off! I got tired of staying with the tarnation fool, who couldn’t tell me a thing, when I heard you shooting, and the horn blowing for the men; and knowing the bar was dead, I started off full tilt. I hadn’t gone fifty steps before I began to see where his bullets had spattered the trees and bushes in every direction. Presently I stumbled over these dogs, my own puppies—and there they lay as dead as door nails. I whistled, and they didn’t move; I then stooped down to see how the bear had killed ’em, and I found these bullet holes in ’em!” said Sneak, turning their limber bodies over with his foot, until their wounds were uppermost. “I’ll be shot if I don’t have pay, or revenge!” he continued, with tears in his eyes.

“What were they worth?” demanded Glenn, laughing.

“I was offered two dollars a-piece for ’em as we came through Indiana,” replied Sneak.

“Here’s the money,” said Glenn, handing him the amount. After receiving the cash, Sneak turned away perfectly satisfied, and seemed not to bestow another thought upon his puppies.

This affair had hardly been settled before Joe made his appearance on Pete. He rode slowly along down the path, as dolefully as ever man approached the graveyard. As he drew near, all eyes were fixed upon him. Never were any one’s features so much disfigured. His nose was as large as a hen’s egg, and as purple as a plum. Still it was not much disproportioned to the rest of his swollen face; and the whole resembled the unearthly phiz of the most bloated gnome that watched over the slumbers of Rip Van Winkle.

Glenn’s castle—Mary—Books—A hunt—Joe and Pete—A tumble—An opossum—A shot—Another tumble—A doe—The return—They set out again—A mound—A buffalo—An encounter—Night—Terrific spectacle—Escape—Boone—Sneak—Indians.

Some weeks had passed since the bear hunt. The emigrants had crossed the river, and selected their future homes in the groves that bordered the prairie, some miles distant from the ferry. Glenn, when landed on the south side of the Missouri, took up his abode for a short time with Jasper Roughgrove, the ferryman, while some half dozen men, whose services his gold secured, were building him a novel habitation. And the location was as singular as the construction of his house. It was on a peak that jutted over the river, some three hundred feet high, whence he had a view eight or ten miles down the stream, and across the opposite bottom-land to the hills mentioned in the preceding chapter. The view was obstructed above by a sudden bend of the stream; but on the south, the level prairie ran out as far as the eye could reach, interrupted only by the young groves that were interspersed at intervals. His house, constructed of heavy stones, was about fifteen feet square, and not more than ten in height. The floor was formed of hewn timbers, the walls covered with a rough coat of lime, and the roof made of heavy boards. However uncouth this abode appeared to the eye of Glenn, yet he had followed the instructions of Boone, (to whom he had fully disclosed his plan, and repeated his odd resolution,) and reared a tenement not only capable of resisting the wintry winds that were to howl around it, but sufficiently firm to withstand the attacks of any foe, whether the wild beast of the forest or the prowling Indian. The door was very narrow and low, being made of a solid rock full six inches in thickness, which required the strength of a man to turn on its hinges, even when the ponderous bolt on the inside was unfastened. There was a small square window on each side containing a single pane of glass, and made to be secured at a moment’s warning, by means of thick stone shutters on the inside. The fire-place was ample at the hearth, but the flue through which the smoke escaped was small, and ran in a serpentine direction up through the northern wall; while the ceiling was overlaid with smooth flat stones, fastened down with huge iron spikes, and supported by strong wooden joists. The furniture consisted of a few trunks, (which answered for seats,) two camp beds, four barrels of hard biscuit, a few dishes and cooking utensils, and a quantity of hunting implements. Many times did Joe shake his head in wonderment as this house was preparing for his reception. It seemed to him too much danger was apprehended from without, and it too much resembled a solitary, and secure prison, should one be confined within. Nevertheless, he was permitted to adopt his own plan in the construction of a shelter for the horses. And the retention of these animals was some relief to his otherwise gloomy forebodings, when he beheld the erection of his master’s suspicious tenement. He superintended the building of a substantial and comfortable stable. He had stalls, a small granary, and a regular rack made for the accommodation of the horses, and procured, with difficulty and no little expense, a supply of provender. The space, including the buildings, which had been cleared of the roots and stones, for the purpose of cultivating a garden, was about one hundred feet in diameter, and enclosed by a circular row of posts driven firmly in the ground, and rising some ten feet above the surface. These were planted so closely together that even a squirrel would have found it difficult to enter without climbing over them. Indeed, Joe had an especial eye to this department, having heard some awful tales of the snakes that somewhat abounded in those regions in the warm seasons.

One corner of the stable, wherein a quantity of straw was placed, was appropriated for the comfort of the dogs, Ringwood and Jowler, which had been presented to Glenn by his obliging friend, after they had exhibited their skill in the bear hunt.

When every thing was completed, preparatory for his removal thither, Glenn dismissed his faithful artisans, bestowing upon them a liberal reward for their labour, and took possession of his castle. But, notwithstanding the strange manner in which he proposed to spend his days, and his habitual grave demeanour and taciturnity, yet his kind tone, when he uttered a request, or ventured a remark, on the transactions passing around him, and his contempt for money, which he squandered with a prodigal hand, had secured for him the good-will of the ferrymen, and the friendship of the surrounding emigrants. But there was one whose esteem had no venal mixture in it. This was Mary, the old ferryman’s daughter, a fair-cheeked girl of nineteen, who never neglected an opportunity of performing a kind office for her father’s temporary guest; and when he and his man departed for their own tenement, not venturing directly to bestow them on our hero, she presented Joe with divers articles for their amusement and comfort in their secluded abode, among which were sundry live fowls, a pet fawn, and a kitten.

The first few days, after being installed in his solitary home, our hero passed with his books. But he did not realize all the satisfaction he anticipated from his favourite authors in his secluded cell. The scene around him contrasted but ill with the creations of Shakspeare; and if some of the heroes of Scott were identified with the wildest features of nature, he found it impossible to look around him and enjoy the magic of the page at the same time.

Joe employed himself in attending to his horses, feeding the fowls and dogs, and playing with the fawn and a kitten. He also practiced loading and shooting his musket, and endeavoured to learn the mode of doing execution on other objects without committing violence on himself.

“Joe,” said Glenn, one bright frosty morning, “saddle the horses; we will make an excursion in the prairie, and see what success we can have without the presence and assistance of an experienced hunter. I designed awaiting the visit of Boone, which he promised should take place about this time; but we will venture out without him; if we kill nothing, at least we shall have the satisfaction of doing no harm.”

Joe set off towards the stable, smiling at Glenn’s joke, and heartily delighted to exchange the monotony of his domestic employment, which was becoming irksome, for the sports of the field, particularly as he was now entirely recovered from the effects of his late disasters, and began to grow weary of wasting his ammunition in firing at a target, when there was an abundance of game in the vicinity.

“Whoop! Bingwood—Jowler!” cried he, leading the horses briskly forth. The dogs came prancing and yelping round him, as well pleased as himself at the prospect of a day’s sport; and when Glenn came out they exhibited palpable signs of recognition and eagerness to accompany their new master on his first deer-hunt. Glenn stroked their heads, which were constantly rubbed against his hands, and his caresses were gratefully received by the faithful hounds. He had been instructed by Boone how to manage them, so as either to keep them at his side when he wished to approach the game stealthily, or to send them forth when rapid pursuit was required, and he was now anxious to test their sagacity.

When mounted, the young men set forward in a southern direction, the valley in which the ferryman’s cabin was situated on one hand, and one about the same distance above on the other. But the space between them gradually widened as they progressed, and in a few minutes both disappeared entirely, terminating in scarcely perceptible rivulets running slowly down from the high and level prairie. Here Glenn paused to determine what course he should take. The sun shone brightly on the interminable expanse before him, and not a breeze ruffled the long dry grass around, nor disturbed the few sear leaves that yet clung to the diminutive clusters of bushes scattered at long intervals over the prairie. It was a delightful scene. From the high position of our hero, he could distinguish objects miles distant on the plain; and if the landscape was not enlivened by houses and domestic herds, he could at all events here and there behold parties of deer browsing peacefully in the distance. Ringwood and Jowler also saw or scented them, as their attention was pointed in that direction; but so far from marring the sport by prematurely running forward, they knew too well their duty to leave their master, even were the game within a few paces of them, without the word of command.

“I see a deer!” cried Joe, at length, having till then been employed gathering some fine wild grapes from a neighbouring vine.

“I see several,” replied Glenn; “but how we are to get within gun shot of them, is the question.”

“I see them, too,” said Joe, his eyes glistening.

“I have thought of a plan, Joe; whether right or wrong, is not very material, as respects the exercise we are seeking; but I am inclined to believe it is the proper one. It will at all events give you a fair opportunity of killing a deer, as you will have to fire as they run, and the great number of bullets in your musket will make you more certain to do execution than if you fired a rifle. You will proceed to yon thicket, about a thousand yards distant, keeping the bushes all the time between you and the deer. When you arrive at it dismount, and after tying your pony in the bushes where he will be well hid, select a position whence you can see the deer when they run; I think they will go within reach of your fire. I will make a detour beyond them, and approach from the opposite side.”

“I’d rather not tie my pony,” said Joe.

“Why? he would not leave you, even were he to get loose,” replied Glenn.

“I don’t think he would—but I’d rather not leave him yet awhile, till I get a little better used to hunting,” said Joe, probably thinking there might be some danger to himself on foot in a country where bears, wolves, and panthers were sometimes seen.

“Can you fire while sitting on your pony?” inquired Glenn.

“I suppose so,” said Joe; “though I never thought to try it yet.”

“Suppose you try it now, while I watch the deer, and see if what I have been told is true, that the mere report of a gun will not alarm them.”

“Well, I will,” said Joe. “I think Pete knows as well as the steed, that shooting on him won’t hurt him.”

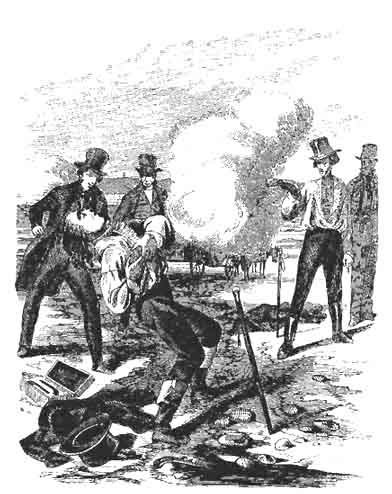

“Fire away, then,” said Glenn, looking steadfastly at the deer. Joe fired, and none of the deer ran off. Some continued their playful sports, while others browsed along without lifting their heads; in all likelihood the report did not reach them. But Glenn heard a tremendous thumping behind, and on turning round, beheld his man quietly lying on the ground, and the pony standing about ten paces distant, with his head turned towards Joe, his ears thrust forwards, his nostrils distended and snorting, and his little blue eyes ready to burst out of his head.

Glenn heard a tremendous thumping behind.

“How is this, Joe?” inquired Glenn, scarce able to repress a smile at the ridiculous posture of his man.

“I hardly know myself,” replied Joe, casting a silly glance at his treacherous pony; and after examining his limbs and finding no injury had been sustained, continued, “I fired as you directed, and when the smoke cleared away, I found myself lying just as you see me here. I don’t know how Pete contrived to get from under me, but there he stands, and here I lie.”

“Load your gun, and try it again,” said Glenn.

“I’d rather not,” said Joe.

“Then I will,” replied Glenn, whose horsemanship enabled him to retain the saddle in spite of the straggles of Pete, who, after several discharges, submitted and bore it quietly.

Joe then mounted and set out for the designated thicket, while Glenn galloped off in another direction, followed by the hounds.

When Joe arrived at the hazel thicket, he continued in the saddle, and otherwise he would not have been able to see over the prairie for the tall grass which had grown very luxuriantly in that vicinity. There was a path, however, running round the edge of the bushes, which had been made by the deer and other wild animals, and in this he cautiously groped his way, looking out in every direction for the deer. When he had progressed about halfway round, he espied them feeding composedly, about three hundred paces distant, on a slight eminence. There were at least fifteen of them, and some very large ones. Fearful of giving the alarm before Glenn should fire, he shielded himself from view behind a cluster of persimmon bushes, and tasted the ripe and not unpalatable fruit. And here he was destined to win his first trophy as a hunter. While bending down some branches over head, without looking up, an opossum fell upon his hat, knocking it over his eyes, and springing on the neck of Pete, thence leaped to the ground. But before it disappeared Joe had dismounted, and giving it a blow with the butt of his musket it rolled over on its side, with its eyes closed and tongue hanging out, indicating that the stroke had been fatal.

“So much for you!” said Joe, casting a proud look at his victim; and then leaping on his pony, he gazed again at the deer. They seemed to be still entirely unconscious of danger, and several were now lying in the grass with their heads tip, and chewing the cud like domestic animals. Joe drew back once more to await the action of Glenn, and turning to look at the opossum, found to his surprise that it had vanished!

“Well, I’m the biggest fool that ever breathed!” said he, recollecting the craftiness imputed to those animals, and searching in vain for his game. “If ever I come across another, he’ll not come the ’possum over me, I’ll answer for it!” he continued, somewhat vexed. At this juncture Glenn’s gun was heard, and Joe observed a majority of the deer leaping affrighted in the direction of his position. The foremost passed within twenty yards of him, and, his limbs trembling with excitement, he drew his gun up to his shoulder and pulled the trigger. It snapped, perhaps fortunately, for his eyes were convulsively closed at the moment; and recovering measurably by the time the next came up, this trial the gun went off, and he found himself once more prostrate on the ground.

“What in the world is the reason you won’t stand still!” he exclaimed, rising and seizing the pony by the bit. The only answer Pete made was a snort of unequivocal dissatisfaction. “Plague take your little hide of you! I should have killed that fellow to a certainty, if you hadn’t played the fool!” continued he, still addressing his pony while he proceeded to load his gun. When ready for another fire, he mounted again, in quite an ill humour, convinced that all chance of killing a deer was effectually over for the present, when, to his utter astonishment, he beheld the deer he had fired at lying dead before him, and but a few paces distant. With feelings of unmixed delight he galloped to where it lay, and springing to the earth, one moment he whirled round his hat in exultation, and the next caressed Pete, who evinced some repugnance to approach the weltering victim, and snuffed the scent of blood with any other sensation than that of pleasure. Joe discovered that no less than a dozen balls had penetrated the doe’s side, (for such it was,) which sufficiently accounted for its immediate and quiet death, that had so effectually deceived him into the belief that his discharge had been harmless. He now blew his horn, which was answered by a blast from Glenn, who soon came up to announce his own success in bringing down the largest buck in the party, and to congratulate his man on his truly remarkable achievement.

An hour was consumed in preparing the deer to be conveyed to the house, and by the time they were safely deposited in our hero’s diminutive castle, and the hunters ready to issue forth in quest of more sport, the day was far advanced, and a slight haziness of the atmosphere dimmed in a great measure the lustre of the descending sun.

Animated with their excellent success, they anticipated much more sport, inasmuch as neither themselves nor the hounds (which hitherto were not required to do farther service than to watch one of the deer while the men were engaged with the other) were in the slightest degree fatigued. The hours flew past unnoticed, while the young men proceeded gayly outward from the river in quest of new adventures.

Glenn and his man rode far beyond the scene of their late success without discovering any new object to gratify their undiminished zest for the chase. It seemed that the deer which had escaped had actually given intelligence to the rest of the arrival of a deadly foe in the vicinity, for not one could now be seen in riding several miles. The sun was sinking low and dim in the west, and Glenn was on the eve of turning homeward, when, on emerging from the flat prairie to a slight eminence that he had marked as boundary of his excursion, he beheld at no great distance an enormous mound, of pyramidical shape, which, from its isolated condition, he could not believe to be the formation of nature. Curious to inspect what he supposed to be a stupendous specimen of the remains of former generations of the aborigines, he resolved to protract his ride and ascend to the summit. The mound was some five hundred feet in diameter at the base, and terminated at a peak about one hundred and fifty feet in height. As our riders ascended, with some difficulty keeping in the saddle, they observed the earth on the sides to be mixed with flint-stones, and many of them apparently having once been cut in the shape of arrow-heads; and in several places where chasms had been formed by heavy showers, they remarked a great many pieces of bones, but so much broken and decayed they could not be certain that they were particles of human skeletons. When they reached the summit, which was not more than twenty feet in width and entirely barren, a magnificent scene burst in view. For ten or fifteen miles round on every side, the eye could discern oval, oblong, and circular groves of various dimensions, scattered over the rich virgin soil. The gentle undulations of the prairie resembled the boundless ocean entranced, as if the long swells had been suddenly abandoned by the wind, and yet remained stationary in their rolling attitude.

“What think you of the view, Joe?” inquired Glenn, after regarding the scene many minutes in silence.

“I’ve been watching a little speck, way out toward the, sun, which keeps bobbing up and down, and gets bigger and bigger,” said Joe.

“I mean the prospect around,” said Glenn. I can’t form an opinion, because I can’t see the end of it,” replied Joe, still intently regarding the object referred to.

“That is an animal of some kind,” observed Glenn, marking the object that attracted Joe.

“And a wapper, too; when I first saw it I thought it was a rabbit, and now it’s bigger than a deer, and still a mile or two off,” said Joe.

“We’ll wait a few minutes, and see what it is,” replied Glenn, checking his steed, which had proceeded a few steps downward. The object of their attention held its course directly towards them, and as it drew nearer it was easily distinguished to be a very large buffalo, an animal then somewhat rare so near the white man’s settlement, and one that our hero had often expressed a wish to see. Its dark shaggy sides, protuberant back and bushy head, were quite perceptible as it careered swiftly onward, seemingly flying from some danger behind.

“Down, Ringwood! Jowler!” exclaimed Glenn, preparing to fire.

“Down, Joe, too,” said Joe, slipping down from his pony, preferring not to risk another fall, and likewise preparing to fire.

When the buffalo reached the base of the mound, it saw for the first time the objects above, and halted. It regarded the men with more symptoms of curiosity than alarm, but as it gazed, its distressed pantings indicated that it had been long retreating from some object of dread.

Meantime both guns were discharged, and the contents undoubtedly penetrated the animal’s body, for he leapt upright in the air, and on descending, staggered off slowly in a course at right angles from the one which he was first pursuing. Glenn then let the hounds go forth, and soon overtaking the animal, they were speedily forced to act on the defensive; for the enormous foe wheeled round and pursued in turn. Finding the hounds were too cautious and active to fall victims to his sharp horns, he pawed the earth, and uttered the most horrific bellowings. As Glenn and Joe rode by the place where he had stood when they fired, they perceived large quantities of frothy blood, which convinced them that he had received a mortal wound. They rode on and paused within eighty paces of where he now stood, and calling back the baying hounds, again discharged their guns. The buffalo roared most hideously, and making a few plunges towards his assailants, fell on his knees, and the next moment turned over on his side.

“Come back, Joe!” cried Glenn to his man, who had mounted and wheeled when the animal rushed towards them, and was still flying away as fast as his pony could carry him.

“No—never!” replied Joe; “I won’t go nigh that awful thing! Don’t you see it’s getting dark? How’ll we over find the way home again?”