Mrs. G.-G. GALAHAD!

Mr. G.-G. (meekly). My love?

Mrs. G.-G. I see that the proprietors of All Sorts are going to follow the American example, and offer a prize of £20 to the wife who makes out the best case for her husband as a Model. It's just as well, perhaps, that you should know that I've made up my mind to enter you!

Mr. G.-G. (gratified). My dear CORNELIA! really, I'd no idea you had such a—

Mrs. G.-G. Nonsense! The drawing-room carpet is a perfect disgrace, and, as you can't, or won't, provide the money in any other way, why—Would you like to hear what I've said about you?

Mr. G.-G. Well, if you're sure it wouldn't he troubling you too much, I should, my dear.

Mrs. G.-G. Then sit where I can see you, and listen. (She reads.) "Irreproachable in all that pertains to morality"—(and it would be a bad day indeed for you, GALAHAD, if I ever had cause to think otherwise.')—"morality; scrupulously dainty and neat in his person"—(ah, you may well blush, GALAHAD, but, fortunately, they won't want me to produce you!)—"he imports into our happy home the delicate refinement of a preux chevalier of the olden time." (Will you kindly take your dirty boots off the steel fender!) "We rule our little kingdom with a joint and equal sway, to which jealousy and friction are alike unknown; he, considerate and indulgent to my womanly weakness,"—(You need not stare at me in that perfectly idiotic fashion!)—"I, looking to him for the wise and tender support which has never yet been denied. The close and daily scrutiny of many years has discovered"—(What are you shaking like that for?)—"discovered no single weakness; no taint or flaw of character; no irritating trick of speech or habit." (How often have I told you that I will not have the handle of that paper-knife sucked? Put it down; do!) "His conversation—sparkling but ever spiritual—renders our modest meals veritable feasts of fancy and flows of soul ... Well, GALAHAD?

Mr. G.-G. Nothing, my dear; nothing. It struck me as well,—a trifle flowery, that last passage, that's all!

Mrs. G.-G. (severely). If I cannot expect to win the prize without descending to floweriness, whose fault is that, I should like to know? If you can't make sensible observations, you had better not speak at all. (Continuing,) "Over and over again, gathering me in his strong loving arms, and pressing fervent kisses upon my forehead, he has cried, 'Why am I not a Monarch that so I could place a diadem upon that brow? With such a Consort, am I not doubly crowned?'" Have you anything to say to that, GALAHAD?

Mr. G.-G. Only, my love, that I—I don't seem to remember having made that particular remark.

Mrs. G.-G. Then make it now. I'm sure I wish to be as accurate as I can. [Mr. G.-G. makes the remark—but without fervour.

Mr. M.-J. Twenty quid would come in precious handy just now, after all I've dropped lately, and I mean to pouch that prize if I can—so just you sit down, GRIZZLE, and write out what I tell you; do you hear?

Mrs. M.-J. (timidly). But, MONARCH, dear, would that be quite fair? No, don't be angry, I didn't mean that—I'll write whatever you please!

Mr. M.-J. You'd better, that's all! Are you ready? I must screw myself up another peg before I begin. (He screws.) Now, then. (Stands over her and dictates.) "To the polished urbanity of a perfect gentleman, he unites the kindly charity of a true Christian." (Why the devil don't you learn to write decently, eh?) "Liberal, and even lavish, in all his dealings, he is yet a stern foe to every kind of excess"—(Hold on a bit, I must have another nip after that)—"every kind of excess. Our married life is one long dream of blissful contentment, in which each contends with the other in loving self-sacrifice." (Haven't you corked all that down yet!) "Such cares and anxieties as he has, he conceals from me with scrupulous consideration as long as possible"—(Gad, I should be a fool if I didn't!)—"while I am ever sure of finding in him a patient and sympathetic listener to all my trifling worries and difficulties."—(Two f's in difficulties, you little fool—can't you even spell?) "Many a time, falling on his knees at my feet, he has rapturously exclaimed, his accents broken by manly emotion, 'Oh, that I were more worthy of such a pearl among women! With such a helpmate, I am indeed to be envied!'" That ought to do the trick. If I don't romp in after that!—(Observing that Mrs. M.-J.'s shoulders are convulsed.) What the dooce are you giggling at now?

Mrs. M.-J. I—I wasn't giggling, MONARCH dear, only—

Mr. M.-J. Only what?

Mrs. M.-J. Only crying!

"The Judges appointed by the spirited proprietors of All Sorts to decide the 'Model Husband Contest'—which was established on lines similar to one recently inaugurated by one of our New York contemporaries—have now issued their award. Two competitors have sent in certificates which have been found equally deserving of the prize; viz., Mrs. CORNELIA GALAHAD-GREEN, Graemair Villa, Peckham, and Mrs. GRISELDA MONARCH-JONES, Aspen Lodge, Lordship Lane. The sum of Twenty Pounds will consequently be divided between these two ladies, to whom, with their respective spouses, we beg to tender our cordial felicitations."—(Extract from Daily Paper, some six months hence.)

For some months Society has been on the tip-toe of expectation with regard to the new Tragedy by Mr. SHAKSPEARE SMITHSON, which is to inaugurate the magnificent Theatre, built at a sumptuous and total disregard of expense by Mr. DILEY PUFF, a lineal descendant of the great PUFF family, by intermarriage with the more recent CRUMMLES's, expressly for the performance of the genuine English Drama. A veil of secrecy has, however, been drawn over all the arrangements connected with the new production. One after another the Author, the Manager, and the leading Actors were appealed to in vain. Finally, one of Our Representatives taking his courage in both hands, brought it and himself safely to the stage-door of the new theatre, and knocked. After some hesitation he was admitted by an intelligent boy, who, however, at first seemed indisposed to be drawn into conversation, though he admitted he had been engaged for the responsible post of call-boy at an inadequate salary. Our Representative managed to interest the lad in the inspection of a numismatic representation of Her Most Gracious Majesty, which he happened to have brought with him on the back of half-a-crown, and with which Our Representative toyed, holding it between the thumb and dexter finger of the right hand. We give the result in Our Representative's own words:—

"Come this way," said the boy, on whom the sight of the coin seemed to operate like some weird talisman, leading me to a remote part of the stage, the floor of which had been tastefully littered with orange-peel in a variety of patterns; "we shall be comfortabler."

"Now tell me," I said, "about this new piece."

"It's what they call a Tragedy," said the boy.

"Ah!" I replied, "that is interesting; but I want to know about the Author. What do you think of him?"

"The horther? Oh my!" said the precocious lad, producing an apple from his trousers' pocket, but his right eye still fixed on the talisman, "'e don't count. Why we none of us pays no attention to 'im. Crikey, you should 'a seen 'im come a cropper on his nut down them new steps. But, look 'ere, Sir," he continued, more solemnly, "I'm a tellin' yer secrets, I am; and if DILEY were to 'ear of it, I'd get a proper jacketin'. Swear you won't peach."

I gave the requisite pledge. "And that ere arf-crown?" he said. I nodded assent to what was evidently in his mind. Then he resumed. "It's a beautiful piece. The play, I mean," he explained; being fearful lest I should consider him as over-eager for the coveted and covenanted reward. "I'm sure o' that. The horther says so, and DILEY says so, and Miss O'GRADY says so; she's got the 'eroine to play,—and oh, don't she die in the lawst Act just proper, with pink light and a couple o' angels to carry 'er up! Then there's Mr. KEANE 'ARRIS, 'e touches 'em all up with 'is sword, 'places his back to the wall, and defies the mob,' is what the book says. So you may take it from me, it's fust-rate."

I thanked my intelligent little friend for his information, and was proceeding to put a further question about the music for this new Drama, which, as everyone will soon know, is to be a real chef d'oeuvre of Sir HAUTHOR SUNNIVUN, when a step was heard approaching across the stage—the deepest, by the way, in London—to where we were talking.

"That's 'im," said the boy, trembling. "'E's a noble-'earted master, so kind and generous, but 'e 'ates deception, and it would be more than my place is worth to let 'im catch me talking these 'ere dead secrets to you. Give us the coin. I'm orf!"

And, before I was able to carry out my portion of the contract, he was gone. And in another moment—so was I.

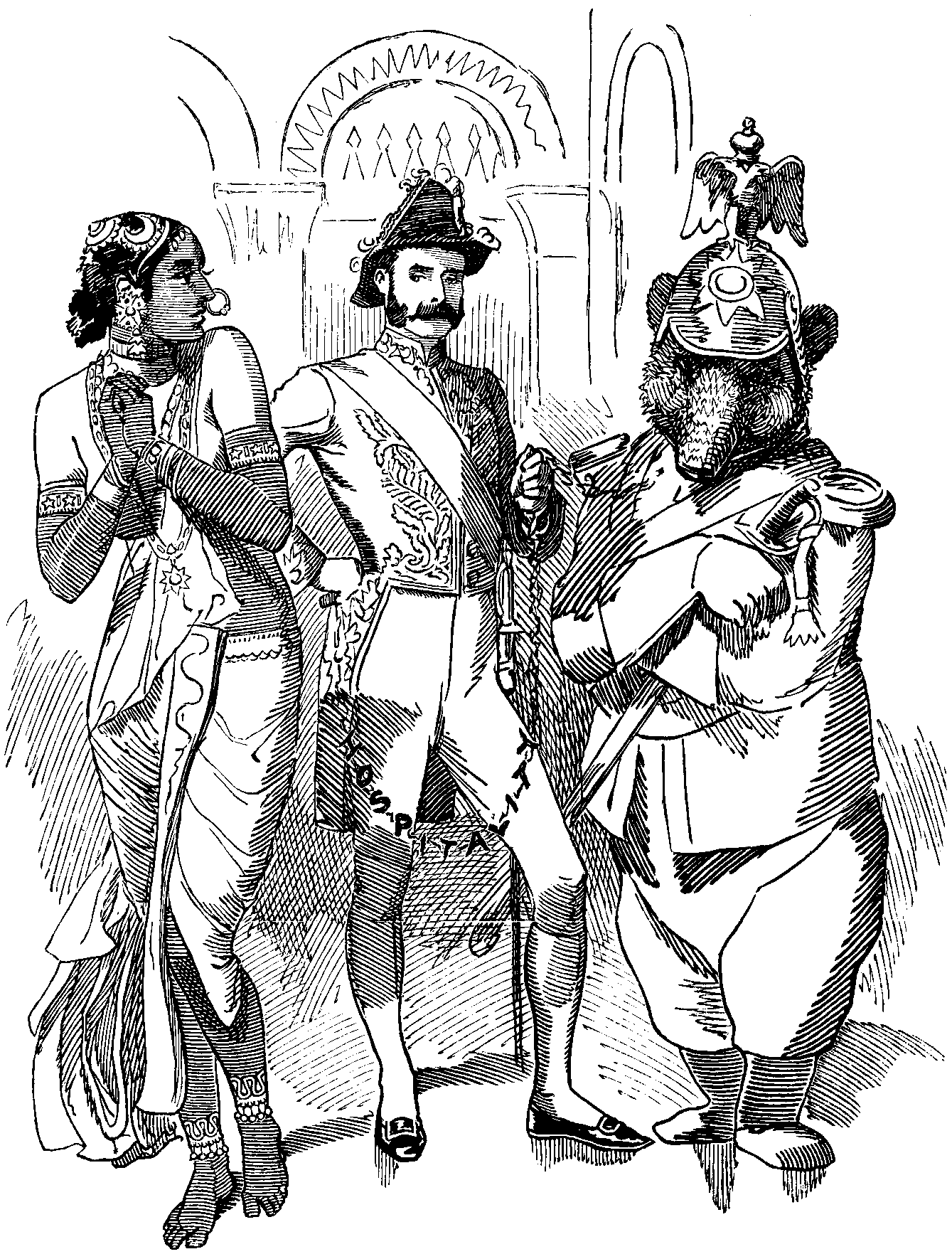

Viceroy (to Miss

India, loquitur). "DON'T BE ALARMED, MY DEAR! THIS

BEAR NEVER DANCES BUT TO THE VERY GENTEELEST OF

TUNES!"

Viceroy (to Miss

India, loquitur). "DON'T BE ALARMED, MY DEAR! THIS

BEAR NEVER DANCES BUT TO THE VERY GENTEELEST OF

TUNES!"Lord LANSDOWNE, loquitur:—

Be easy, my darling! He doesn't come snarling,

Or rearing, or hugging, this young Dancing Bear.

With you (and with pleasure) he'll tread a gay measure,

A captive of courtesy, under my care;

His chain is all golden. Your heart 'twill embolden,

And calm that dusk bosom which timidly shrinks.

Sincere hospitality is, in reality,

Safest of shackles;—just look at the links!

Alarmists saw ruin in prospects of Bruin,

The Great Northern Bear, treading India's soil.

How bogies may blind us! On our side the Indus

They fancy friend Ursa spies nothing but spoil;

But Ursa's invited to come, and delighted

To visit you, not as aggressor, but guest.

So welcome him brightly, and treat him politely.

And trip with him lightly, you'll find it far best,

ATTA TROLL (HEINE tells us) "danced nobly." Pride swells us

To think our young guest is a true ATTA TROLL;

No Bugbear, though shaggy, a trifle breech-baggy,

And not altogether a dandyish doll;

No Afghan intrigue, dear, or shy Native league, dear,

Has brought Bruin's foot o'er our frontier to dance:

He comes freely, boldly—don't look on him coldly,

Or make him suspect there is fear in your glance.

Be sure that the Lion will still keep his eye on

All Bears and their dens, in the Tiger's behalf;

Meanwhile Ursa Minor eschews base design, or

Intrigue against you, dear. Lift eyes, love, and laugh!

I'll answer for Bruin, he shall not take you in—

The Bear's bona fides nobody impugns;

He asks a kind glance, and your hand in a dance; and

He'll dance "to the very genteelest of tunes"!

He (at the end of a turn). I see there's been a row in Chili—what do you think about it?

She. I don't know the place—isn't it somewhere in America?

He. I shouldn't be surprised if it were, but my geography's shaky. I rather fancy it's somehow connected with pickles.

She. Oh, then it's a mistake their quarrelling, as I suppose it will be hard upon the poor, especially during the winter?

He. Fancy that's the idea. Been to the Guelph Exhibition?

She. Yes, and I think it's a pity they took the jewels out of GEORGE THE FOURTH's Crown. I should like to have seen the Koh-i-Noor.

He. But they wanted them for the one at the Tower, don't you know, and as for the Koh-i-Noor, was that invented in his time?

She. Perhaps it wasn't. Stay, wasn't it discovered by Captain COOK, or DRAKE, or somebody?

He. I daresay. I have never looked the matter up. À propos, One-pound Bank-notes are to be issued.

She. Are they? I suppose they will be useful for change?

He. Shouldn't be astonished, but don't pretend to know anything about it. By the way, do you take much interest in the subjects we have been discussing?

She. Not the faintest.

He. No more do I! [Waltz continued.

"Spanish onions are rising in price, though probably only temporarily."—Daily News.

I.

Will it be long, then—long?

For the people watch and wait,

Till the strength of the onion makes them strong,

At only the normal rate.

And their eyes are dim with tears,

And ache with the need of sleep.

And watch till the lapse of the lapsing years

Shall make the onions cheap.

Cheap, my love, cheap! Sleep, my love, sleep!

Onions are dear, love, but sentiment's cheap!

II.

Listen! Is it a voice

Calling—again—again,

Or a fragrance to make my heart rejoice

From the sunlit land of Spain?

Listen, my own, my bride,

While the glad tears dew your cheek,

They are fried, my bride, by the sad sea tide

With a smell that can almost speak

Creep, my love, creep into the deep,

And sing to the fishes that onions are cheap.

THE PROPOSED ONE-POUND NOTES.—"Ne-Goschenable currency."

Good patriots all of every sort,

Give ear unto my song,

For if in substance it is short,

In moral it is strong.

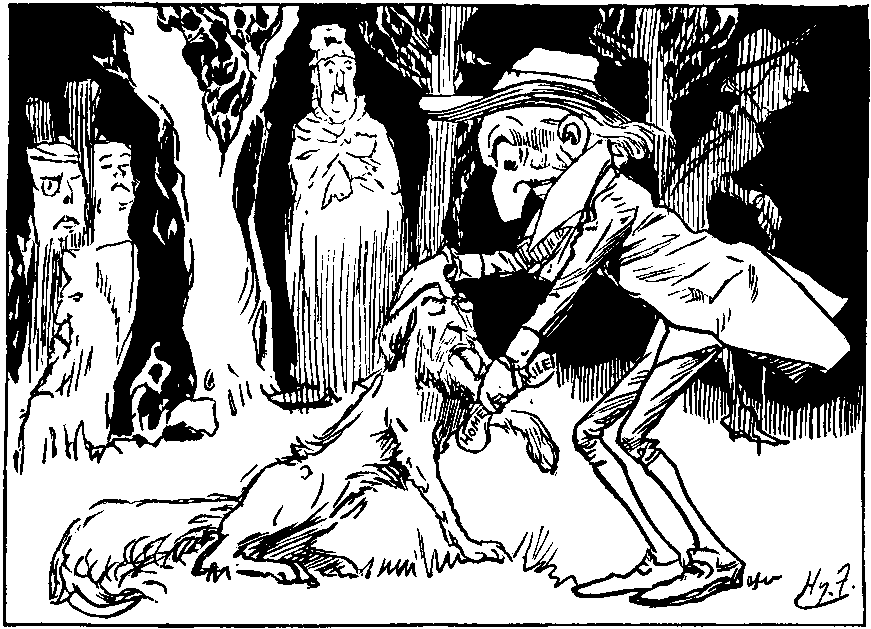

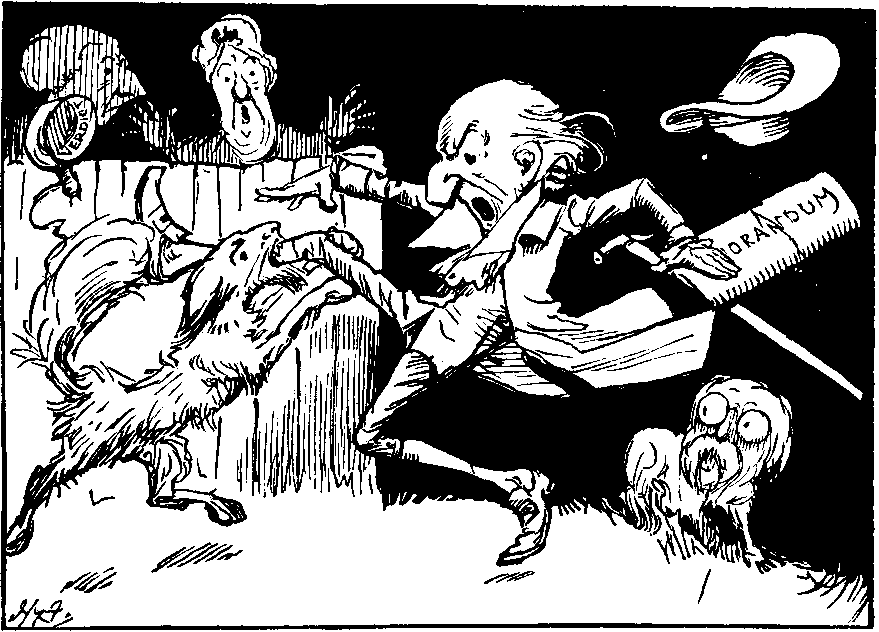

At Hawarden lived a Grand Old Man,

Of whom the world might say,

A wondrous lengthy race he ran,

And won it all the way.

Some swore he'd veer to catch a vote;

Old age to flout one loathes,

But, if he never turned his coat,

He often changed his clothes.

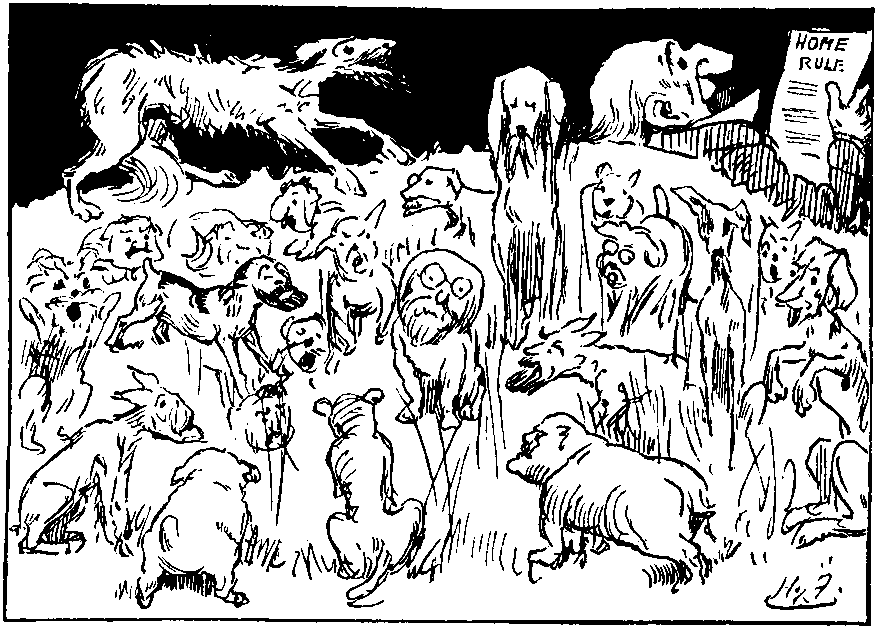

Hard by an Irish dog was found,

As many dogs there be,

Hibernian mongrel, puppy, hound,

And curs of low degree.

This dog and man at first seemed friends,

But, when a pique began,

The dog, to gain his private ends,

Went mad, and bit the man!

To see so strange and sad a sight

Quidnuncs and gobemouches ran,

And swore the dog was rabid quite

To bite that Grand Old Man.

The wound indeed seemed sore and sad

To every party eye,

And while they swore the dog was mad,

They swore the man must die.

But marvels sometimes come to light

Rash prophets to belie.

The man seems healing of the bite,

The dog looks like to die!

"CANON TEIGNMOUTH SHORE proposes to convert the two Convocations." ... that is startling without the context—"into one National Synod." But two into one won't go. How will he manage it? Will those in the York ship join the Canterbury, or vice versâ? Or, quitting both ships, will they land on common ground? "Who's for SHORE?"

PAR ABOUT PICTURES.—"Over the Garden Wall," seems to be the song that Mr. G.S. ELGOOD sings at the Fine Art Society's Gallery. In the course of his travels he has been over a good many garden walls. At Wroxton, Compton Wynyates, Penshurst, Montacute, Berkeley, and Helmingham, he has pursued his studies to some purpose; the result is an enjoyable collection of pictures, which he entitles, "A Summer among the Flowers."

BEN BRUSTLES was only a poor shoeblack-boy who cleaned boots—ay, and even shoes, for his daily bread. Such time as he could spare from his avocation he devoted to diligent study of the doctrine of chance, as exemplified in the practice of pitch-and-toss. Often and often, after pitching and tossing in the cold wet streets for long weary hours, he would return home without a halfpenny. Think of this, ye more fortunate youths, who sit at home at ease, and play Loto for nuts! But through all his vicissitudes, BEN kept a stout heart, never losing his conviction that something—he knew not what—would eventually turn up. Sometimes it was heads, at others tails: and in either case the poor boy lost money by it—but he persevered notwithstanding, confident that Fortune would favour him at last. It is this spirit of undaunted enterprise that has made our England what it is!

And one day Fortune did favour him. He observed, as he knelt before his box, a portly and venerable person close by, who was engrossed in studying, with apparent complacency, his own reflection in a plate-glass shop-front. So naïve a display of personal vanity, in one whose dress and demeanour denoted him a Bishop, not unnaturally excited BENJAMIN's interest, nor was this lessened when the stranger, after shaking his head reproachfully at his reflected image, advanced to the shoe-black's box as if in obedience to a sudden impulse.

"My lad," he said, with a certain calm dignity, "will you be so good as to black both my legs for me—at once?"

This unusual request, conceived as it was on a larger scale than the orders he habitually received, startled the youth, particularly as he noted that the symmetrical and well-turned limb which the Bishop extended consisted, like its fellow, of a rare and costly species of mahogany, and shone with the rich and glossy hue of a newly-fallen horse-chestnut, "I see," commented the Bishop, with a melancholy smile, "that you have already discovered that my lower members are the product—not of Nature, but of Art. It was not always thus with me—but in my younger days I was an ardent climber—indeed, I am still an Honorary Member of the Hampstead Heath Alpine Club. Many years since, whilst scaling Primrose Hill, I was compelled, by a sudden storm, to take refuge in a half-way hut, where I passed the night, exposed to all the rigours of an English Midsummer! When I awoke I found, to my surprise, that both my legs had been bitten by the relentless frost short off immediately below the knee, and I had to continue the ascent next day in a basket. On descending, I caused these substitutes to be fashioned, and on them I stumped my way to the exalted position I now fill, nor have I ever evinced any physical inconveniences from my misfortune, save in one particular—that it has rendered the assumption of gaiters unhappily out of the question! But, possibly, my wish to have these legs of mine disguised by your pigments, strikes you as bizarre, if not positively eccentric? You will better understand my reasons after you have heard a confession which, though necessary, is, believe me, painful to make." And the good old man, after a short internal struggle, began the following narrative, which we reserve for a succeeding chapter.

"Even as a Curate, a certain harmless vanity was ever my besetting weakness. I might, indeed, have hoped that, after my accident—but see, my good lad, how pride may lurk, even in our very infirmities! These artificial limbs have become a yet subtler snare to me than even those they replaced. I had them constructed, as you see, of the best mahogany—to match the furniture in my dining-room. With ever-increasing pleasure, my eyes have gloried in their grain and gloss, in the symmetry of their curves, in the more than Chinese delicacy of their extremities, until gradually they have trampled upon my better self, they have run away with all my possibilities of moral usefulness! Yes, but this very moment, as I stood admiring their contour at yonder window, the pernicious thought crossed my mind that their appearance would be yet more enhanced if I had them gilded!"

"But, your reverent Lordship," objected BRUSTLES, as the Bishop paused, overcome by humiliation, "it's no use coming to me for that 'ere job!" For, though but a poor boy, he was too honest to accept any commission under false pretences. Gilding, he knew, might—and, in a London atmosphere, soon would—become black, but no boot-polish would ever assume the appearance, even of the blackest gilt, and so he candidly explained to the Bishop.

"I know, my boy," said the latter, patting BEN's head kindly with the handle of his umbrella, "I know. Hence my application to your skill. That presumptuous idea revealed as in a lightning flash the abyss on the brink of which I stood. This demon of perverse pride must be laid; humbled for ever. So ply your brushes, and see you spare not the blacking!"

BRUSTLES obeyed—not without awe, and in a short space of time two pots of blacking were exhausted, and the roseate glow of the Bishop's mahogany limbs was for ever hidden under a layer of more than Nubian ebony!

"'Selp me, your lordly reverence," he cried, dazzled by the brilliancy of the result; "but you might be took, below, for a Lifeguardsman!"

"Hush," said the Bishop, though with a gratification he could not restrain, "would you recall the demon I strove to exorcise! It is true that the change is less of a disfigurement than I feared—ahem, hoped—but after all, may not the wish to please the eye of man be excusable? You shall receive a rich reward. Do you happen to have such a thing as change for a five-pound note about you?"

"Alas!" replied the lad, with ready presence of mind, "but I have only just paid all my gold into my bank for the day!"

"No matter," said the Bishop, gently. "I find I have a threepenny bit, after all. It is yours!" And the good ecclesiastic, as if to avoid thanks, moved nimbly off, though his eyes still sought the shop-windows as he passed, with even greater complacency than before.

BEN tested the threepenny bit between his teeth—it was a spurious coin; he looked up, but his late customer was already passed out of hearing of his sentiments. He sank down with his head laid amongst his pots and brushes. "Bilked!" he moaned piteously, "bilked—and by a blooming Bishop!"

But mark the sequel. The good Bishop had been quite ignorant that the threepenny bit was a pewter one; quite sincere, for the time, in his determination to subdue his own weakness. Still it was not to be: inbred pride is not so easily vanquished—even by Bishops! The Bishop learned to glory in his blacking far more than he had ever done in the original mahogany. He had it continually renewed, and with the most expensive compositions. He would bend enraptured over the burnished surfaces of his extended legs, gazing, like another Narcissus, at the features he saw so faithfully repeated.

Meanwhile the threepence, base as it was, became the humble instrument of brighter fortunes to BRUSTLES; it showed a marvellous [pg 65] aptitude for turning up tails, which BEN no sooner perceived than he availed himself of a blessing that had, indeed, come to him in disguise!

But the Bishop—what of him? Nemesis overtook him at last. The discontent long smouldering in his diocese broke out into a climax. Thousands of Curates, inflamed by professional agitators, went out on strike, and their first victim was the Bishop of TIMBERTOWS, who was discovered prostrate one dark night by his horrified Chaplain. He had been picketed as a Blackleg!

(Copies of the above may be obtained for distribution, at very reasonable terms, on application to the Author.)

DEAR MR. PUNCH,—According to a well-known Critic, writing of a morning performance of The Doll's House on Tuesday, the 27th ult., at Terry's Theatre, "There is no need to discuss IBSEN's piece any more." I will go a little further, and say, not only should the play be spared discussion, but also performance. All that could be done for this miserable drama (if a work utterly devoid of dramatic interest can be so entitled) was effected some years since, when Breaking a Butterfly, a version with Messrs. HERMAN and JONES as adapters, was played at the Prince's (now Prince of Wales's) Theatre. I believe some one or other has said that that version was misleading, because it modified IBSEN, and did not reveal him in his true colours. This I can readily believe, as my recollection of Breaking a Butterfly merely suggests boredom; whereas, when I consider The Doll's House of Tuesday, I distinctly mingle with boredom a recollection of something that caused a feeling of absolute loathing. That something, I imagine, must be the new matter which was absent from the first version, and crops up in the text of the second, which, according to the Play-bill, appears "in Vol. I. of the authorised edition of IBSEN's Prose Dramas, edited by WILLIAM ARCHER, and published by Mr. WALTER SCOTT." By the way, I must confess that, although the name of the Editor is not familiar to me as a dramatic author, his superintendence of the authorised text seems to have been performed sufficiently creditably to have rendered him as worthy of an honourable prefix as the publisher. Why omit the "Mr."? Now I come to think of it, there is an Englishman, not unconnected with dramatic literature, who is known nowadays as WILLIAM, without the prefix of Mister, but in his own time he was known as Master WILLIAM SHAKSPEARE, and Master he remains. "But this," as Mr. RUDYARD KIPLING might observe, "is quite another WILLIAM."

I have not the original for reference handy, but the version played at Terry's Theatre bears internal evidence of a close translation. An adapter, I fancy, with a free hand would scarcely have made one of the characters use the same exit speech on two occasions. Nils Krogstad does this. He can think of nothing better than, "If I am flung into the gutter, you shall accompany me," repeated twice with the slight variation, "If I am flung into the gutter for the second time, you shall accompany me," used for the last exit. Again, Torvald Helmer has a long monologue in the final Act that a practised playwright would have "broken up" with the assistance of a portrait, or a letter, or something. From this it would appear that the Editor, WILLIAM ARCHER (without the "Mr.") has very faithfully produced the exact translation of the original. To be hypercritical, I might suggest that perhaps occasionally the version is rather too literal. For instance, Torvald Helmer, although he is cursed with one of the most offensive wives known to creation, would scarcely call her "a little lark," which conveys the impression that he is a "gay dog," and one given to the traditional ways of that species of ultra-sociable animals. I have confessed I have not the original before me, so I cannot say whether the title used by IBSEN is "Smalle Larke," but I fancy that a "capering capercailzie," if not actually his words, would be nearer his meaning. A capercailzie is, according to the dictionaries, a bird of "a delicious flavour" and partially "green;" it is also found in Norway "very fine and large," as IBSEN might say. Surely Torvald would have thus described his semi-verdant Nora, finding her distinctly to his taste.

Returning to what I venture to imagine must be "new matter" not in the Herman-plus-Jonesian version, I consider the scene in which Nora chaffs Dr. Rank about his illness absolutely nauseous, and the drink-inspired admiration of husband for wife in the concluding Act repulsive to the last degree. On Tuesday the spectators received the piece with patient apathy; and, this being the case, I could not help feeling that anyone who could single out such a play as suitable for performance before an English audience, could scarcely possess the acumen generally considered a necessary adjunct to the qualifications of an efficient Dramatic Critic. The hero, the heroine, the doctor, as prigs, could only appeal to prigs, and thank goodness the average London theatre-goer is the reverse of a prig. There was but one redeeming point in the play—its conclusion. It ends happily in Nora, forger, liar, and—hem—wedded flirt, being separated from her innocent children.

For the rest, the piece was fairly well acted. But when the Curtain had fallen for the last time, and the audience were departing more in sadness than in anger, I could not help asking myself the question, Had the advantages obtained in witnessing the performance balanced the expense incurred in securing a seat? I am forced to reply in the negative, as I sign myself regretfully,

I see three ladies in a drawing-room, each with a green volume. "What is it?" No, they won't hear. Each one is intent on her volume, and an irritable answer, in a don't bother kind of manner, is all that I can obtain. The novel is Miss BRADDON's latest, One Life, One Love (but three volumes, for all that), in which they are absorbed. Later on, at intervals, I get the volumes, and, raven-like, secrete them. I can quite understand the absorption of my young friends. Marvellous, Miss BRADDON! Very few have approached you in sensation-writing, and none in keeping up sensationalism as fresh as ever it was when first I sat up at night nervously to read Aurora Floyd, and Lady Audley's Secret. In this bad time of year (I am writing when the snow is without, and the North-East wind is engaged in cutting leaves), the Baron recommends remaining indoors with this Three-volume Novel as a between lunch and dinner companion, only don't take it up to your bed-room, and sit over the fire with it, or—but there, I won't mention the consequences. Keep it till daylight doth appear. The Baron being a busy man—no, Sir, not a busy-body,—is grateful to the authors of good short stories in Magazines. Many others agree with the Baron, who wishes to recommend "Saint or Satan" in The Argosy; The story of an "Old Beau," which might have been advantageously abbreviated in Scribner; an odd tale entitled, "The Phantom Portrait," in the Cornhill; which leaves the reader in doubt as to whether he has been egregiously "sold" or not; and, above all, the short and interesting—too short and most interesting—paper on THACKERAY, in Harper's Monthly, with fac-similes of some of the great humorist's most eccentric and most spirited illustrations, conceived in the broadly burlesquing spirit that was characteristic of GILRAY and ROWLANDSON. THACKERAY, philosopher and satirist, who can take us behind the scenes of every show in Vanity fair, who can depict the career of the scoundrel Barry Lyndon, of the heathen Becky Sharp, and the death-bed of the Christian soldier and gentleman, dignissimus, Colonel Newcome, could on occasion, and when a rollicking spirit moved him, put on a pantomime mask (have we not his own pathetic vignette representing him doing this?) to amuse the children, or give us some rare burlesque writing and drawing to set us all on the broad grin. The Baron trusts that Mrs. RITCHIE will give us more of this, and sincerely hopes that there may be a "lot more" caricatures in that portfolio "where these came from." I heartily thank you for so much, and respectfully ask for more, says yours, very gratefully,

Strong man and strenuous fighter, stricken down

Just when foes owned thee neither knave nor clown!

The fiercest of them, time-taught, need not fear

To drop a blossom now on BRADLAUGH's bier.

ARTHUR AND COMPOSER.—Saturday, January 31.—First night of SULLIVAN's Ivanhoe in D'OYLEY CARTE's new Theatre. Full inside, all right. Sir ARTHUR's success. We congratulate him Arthurly, CARTE called before horse,—should say before Curtain, but t'other came so naturally,—looked pale,—quite carte blanche; but, like SULLIVAN's music, composed. Could get a CARTE, but no cab. Gallant gentlemen and delicate ladies braving rain and slosh. More in our next, but for the present ... (Paroxysm of sneezing).

Fair Damsel. "WHAT A LOT OF HOLIDAYS YOU SEEM TO GET, MR. MINIVER!"

Pet Curate. "WELL, YES. I KEEP A RECTOR, YOU KNOW."

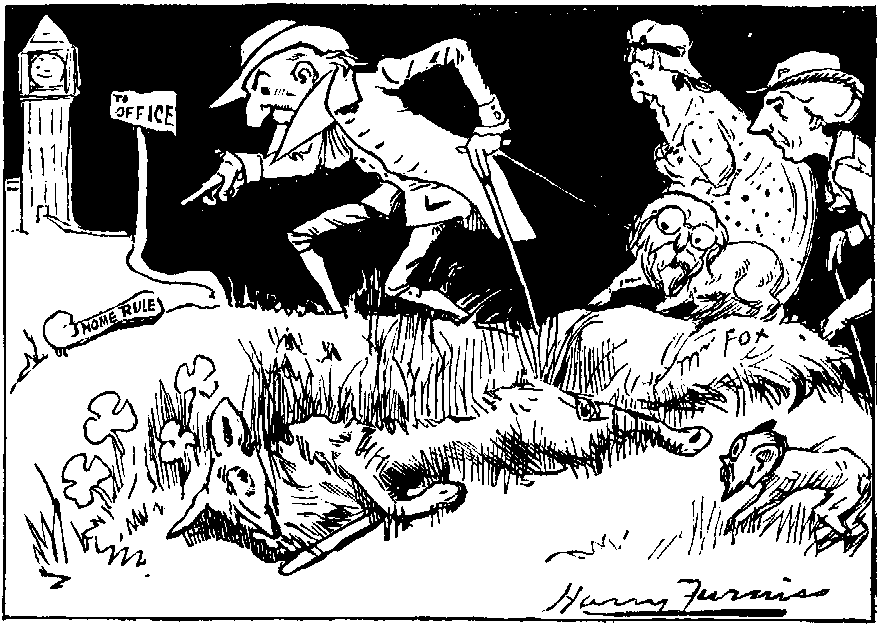

(A Song of the Session, as sung by that Eminent and Evergreen Lion Comique, "JOLLY GLAD" at the St. Stephen's Hall of Varieties, Westminster.)

JOLLY GLAD, sings:—

With a flower in my coat,

With a keen eye for a vote,

And a sense the things to note,

Buff and Blue think,

With fond millions to admire,

A last triumph to desire,—

Am I going to Retire?—

What do you think?

Oh, I know the quidnuncs vapour,

And that Tadpole, yes, and Taper,

Tell in many a twaddling paper,

What the few think;

But they cater for the classes,

Whilst I'm champion of the masses,

Fly before such braying asses?—

What do you think?

Wish is father to their thought,

Their wild hope with fear is fraught.

They are not au fait to aught

Liberals true think.

They imagine "Mr. Fox"

Has delivered such hard knocks

That impasse my pathway blocks!—

What do you think?

Just inspect me, if you please!

Is my pose not marked by ease?

Am I going at the knees,

Like a "screw" Think!

Pooh! The part of Sisyphus

Suits me well. Why make a fuss?

Eh? Retire,—and leave things thus?

What do you think?

On the—say the Lyric Stage—

For some years I've been the rage,

And some histrios touched by age

Of Adieu think.

But I'm like that "Awful Dad,"

Though this makes my rivals mad,

Don't true Gladdyites feel glad?

What do you think?

I'm a genuine Evergreen;

It is that excites their spleen

Who my lingering on the scene

A great "do" think.

I regret, so much, to tease them!

My last exit would much ease them.

But Retire!—and just to please them!

What do you think?

[Winks and walks round.

The other night I went to bed,—

It may seem strange, but still I did it,—

And laid to rest my weary head

So that the bed-clothes nearly hid it;

Which was perhaps the reason why

My brain throughout the night was teeming

With truly wondrous sights, and I

Was wholly given o'er to dreaming.

'Twas on the Twenty-first of May,

The streets were filled to overflowing,

The streets, that in a curious way

Were clean although it kept on snowing.

The daily papers for a change

Came out each day without a leader,

But, what was surely rather strange,

They didn't lose a single reader!

I saw a Bishop in a tram,

Although he knew it was a Sunday;

The lion lay down with the lamb,

And CLEMENT SCOTT with SYDNEY GRUNDY.

Professor HUXLEY said, "In truth

I'm really sick to death of rows," and

Wrote there and then to General BOOTH

To put his name down for a thousand.

I heard that Mr. PARNELL wrote

(Much to McCARTHY's jubilation)

A very kind and civil note,

In which he sent his resignation;

Whilst ANDREW LANG with weary air

Professed himself completely staggered

To think how anyone could care

To read a line of RIDER HAGGARD.

The House of Commons talked about

The case of Mr. BRADLAUGH—whether

The Motion which has kept him out

Should now be struck out altogether;

And OLD MORALITY arose

To say they felt no ancient animus,

And when they voted, why of Noes

There wasn't one—they were unanimous!

I started up, no more to sleep,

The dream somehow had seemed to spoil it,

Nor did it take me long to leap

Out of my bed and make my toilet.

I went down-stairs, and with surprise

I thought of those my dream had slandered,

And there, before my very eyes,

I saw it printed in the STANDARD!

I wish I hadn't gone to bed.

I can't imagine why I did it.

Nor why I laid my weary head

So that the clothes completely hid it.

Although I think that must be why

My brain has ever since been teeming;

But tell me (if you can) am I

At present mad, or was I dreaming?

LITHONODENDRIKON, the new indestructible cloth.

LITHONODENDRIKON is a stubborn and inflexible material.

LITHONODENDRIKON is made, by a new process, from blockwood and paving-stones.

LITHONODENDRIKON, used for gentlemen's coats, will not only keep out rain and wind, but thunder and lightning.

LITHONODENDRIKON never breaks or bends, but only bursts.

LITHONODENDRIKON.—A "PURCHASER" writes—"I sat down in a pair of your trousers, but could never get up again."

LITHONODENDRIKON.—Another "CUSTOMER" says—"The dress-coat you supplied me with fitted me well. I could not take it off without having recourse to a sledge-hammer."

UPPER HOUSE COAL COMPANY supply the cheapest and worst in the market.

UPPER HOUSE COAL COMPANY, hand-picked by the Duke himself, on whose property the mines are situated.

UPPER HOUSE COAL COMPANY, carefully selected, screened and delivered (in the dark), anywhere within a ten-mile radius of Charing Cross at 9s. 6d, a ton, for cash on delivery.

UPPER HOUSE COAL COMPANY supply a wonderful article at the price. Throws down a heavy brown ash. No flame, no heat. Frequently explodes, scattering the contents of the grate over the largest room.

UPPER HOUSE COAL COMPANY beg to refer intending purchasers to the accompanying testimonial: "Gentlemen,—Do what I will, I cannot get your coals to light. Put on in sufficient quantity they will extinguish any fire. I have worn out three drawing-room pokers in my endeavours to stir them into a flame, but all to no purpose. Steeped in petroleum, they might possibly ignite in a double-draught furnace, though I fancy they would put it out. They are as you advertise them, a 'show coal for summer use.' Don't send me any more."

DEAR MR. PUNCH,—Why should ARISTOTLE be the only author whose works get discovered? I found the following story, written on papyrus, and enclosed in a copper cylinder, in my back garden, and I am positive that it is not ARISTOTLE. Can it possibly have been written by that amiable and instructive authoress whose stories for children have recently been reprinted? Yours, &c., HENRY ST. OTLE.

CHARLIE was a very obedient little boy, and his sister SARAH was a good, patient little girl. One beautiful summer's day they went to stay for a week with their Uncle WILLIAM, a man of very high principles, who was not quite used to the proper method with children. On the evening of their arrival, as they were seated in front of the fire, CHARLIE lifted up his bright, obedient, beautiful face, and said, thoughtfully:

"Pray, Uncle WILLIAM, cannot we have one of those instructive and amusing conversations such as children love, about refraction, and relativity, and initial velocity, and Mesopotamia generally?"

"Oh, yes, Uncle WILLIAM!" said SARAH, pausing to wipe her patient little nose; "Our dear Papa is always so pleasant and polysyllabic on these subjects."

Then Uncle WILLIAM regretted that he had paid less attention in his youth to the shilling science primers, but he pulled himself together and determined to do his best. "Certainly, my dear children, nothing could please me more. Now here I have a jug and a glass. You will observe that I pour some water from the jug into the glass. This illustrates one of the properties of water. Can you tell me what I mean?"

"Fluidity!" said both the children, with enthusiasm.

"Yes, quite so, and—er—er—has a brick fluidity?"

"Why, no, Uncle WILLIAM!"

"Well—er—why hasn't it?" asked Uncle WILLIAM, with something almost like desperation in his voice.

"That, Uncle," said the obedient CHARLIE, "is one of the things which we should like to learn from you to-night."

"Yes, we shall come to that; but, in order to make you understand it better, I must carry my experiment a little further. In this decanter I have what is called whiskey. I pour some of it into the water. Now it is more usual to put the whiskey in first, and the water afterwards. Can you tell me why that is so? Think it out for yourselves." And Uncle WILLIAM smiled genially.

There was silence for a few moments. Then little SARAH said, timidly: "I think it must be because, when a man wishes to drink, whiskey is the first thing which naturally occurs to his mind. He does not think about water until afterwards."

"Quite right. That is the explanation of the scientists. And why do you think I put in the water first and the whiskey afterwards?"

"It was," said CHARLIE, brightly, "in order that we might not see so exactly how much whiskey you took."

"No, that's quite wrong. I did it out of sheer originality. Now what would happen if I drank this curious mixture?"

"You would be breaking the pledge, Uncle WILLIAM," said both children, promptly and heartily.

"Wrong again. I should be acting under doctor's orders."

"Why hasn't a brick any fluidity?" asked SARAH, patiently.

"Don't interrupt, my dear child. We're coming to that. Now, CHARLIE, when you eat or drink anything, where does it go?"

"It goes into my little—oh, no, Uncle, I cannot say that word," and CHARLIE, who was of a singularly modest and refined disposition, buried his face in his hands, and blushed deeply.

"Admirable!" exclaimed Uncle WILLIAM. "One cannot be too refined. Call it the blank. It goes into your blank. Well, whiskey raises the tone of the blank. Just as, when you screw up the peg of a violin, you raise the tone of the string. By drinking this I raise the tone of my blank." He suited the action to the word.

"Now you'll be screwed," said CHARLIE, "like the pegs of the—"

"On one glass of weak whiskey-and-water—never!"

"But why hasn't a brick any fluidity?" asked SARAH, quite patiently.

"First of all, listen to this. That whiskey-and-water is now inside me. I want you to understand what inside means. Go and stand in the passage, and shut the door of this room after you."

"But, Uncle," said SARAH, patiently, "why hasn't a brick any—"

"Hush, SARAH, hush!" said the obedient CHARLIE. "It is our duty to obey Uncle WILLIAM in all things."

So the two children went out of the room, and shut the door after them. Uncle WILLIAM went to the door, and locked it.

"Now then," he said, cheerily, "I am inside. And where are you?"

"Outside."

"Yes—and outside you'll stop. One of the servants will put you to bed." And Uncle WILLIAM went back to the decanter.

When I saw you on "a January morning,"

With a very little pair of skates indeed,

And the frosty glow your fairy face adorning,

I was suddenly from other passions freed.

And the year at its imperial beginning

Showed the woman who alone was worth the winning;

Though the growing flame awhile I tried to smother

Like a brother;

And that's a very common phase indeed,

As we read.

My hat and stick I suddenly found fleeting,

And they whistled o'er the surface, smooth and black,

And the ice, with an unwonted warmth of greeting,

Slapt me suddenly and hard upon the back.

I didn't mind your laughing, if the laughter

Had left no sting of scorn to rankle after.

Though I'd joyously have flung myself before you

To adore you,

Still to sit with all one's might upon the ice

Isn't nice.

When I met you in the lordly local ball-room,

Where you queen'd it, the suburban world's desire,

Though your programme for my name had left but small room,

I somehow snatched five valses from the fire.

And I did stout supper-service for your mother,

While you wove the self-same spells o'er many another,

And I said, no doubt, the sort of things that they did,

In the shaded

Little nook beneath the palms upon the stair,

To my fair.

But I noticed, as I learned to know you better,

And you ceased to wile the victim at your feet,

There was very little silk about the fetter,

And 'twere flattery to say your sway was sweet:

Nay, you made the light and airy shrine of beauty

A centre for the most exacting duty,

And the fealty of the family undoubting

Met with flouting,

As a tribute which was nothing but your due,

As they knew.

Your Papa is getting elderly and bulky,

And he loves you as the apple of his eye,

Yet very little things will make you sulky,

And to meet his little ways you never try.

And I see him look a trifle hurt and puzzled,

And his love for you is often check'd and muzzled;

Yet I think, upon the whole, that I would rather

Be your father,

Than the lover you could torture at your ease,

If you please.

Sir,—Under the heading of "Ecclesiastical Intelligence" in the Times of Saturday, I read that, "The LORD CHANCELLOR has preferred the Rev. W.R. WELCH, of Hull, to the Vicarage of Withernwick, East Yorkshire," I presume the LORD CHANCELLOR knows both the gentleman and the place thoroughly, and so wisely elects which he prefers; but to one who, like myself and thousands of others, know neither, it strikes me that I would certainly prefer the place to the parson, however worthy. It is, indeed, gratifying to see that the Highest Representative of Law and Order in the realm, after HER GRACIOUS MAJESTY, is so utterly uninfluenced by any mercenary motives. I send this by Private Post, an old soldier, and am yours enthusiastically,

The Retreat, Hanwell-on-Sea.

"BETTER LATE THAN NEVER."—Two Jurymen, says a paragraph in last Saturday's Times, wrote to the Solicitor acting for a female prisoner, one CUTLER, who had been convicted of perjury and sentenced at Chester, to say that they "gave in to a verdict of Guilty because it was very late, and one gentleman had an important business engagement at home." This recalls the line, "And wretches hang that Jurymen may dine." The remainder of ELLEN CUTLER's sentence of five years' penal servitude is remitted. It is satisfactory to know that these two had the courage of their opinions before it was too late.

[Proceeds to describe his own at great length, and then suddenly finds out how late it is, and bolts!

House of Commons, Monday, Jan. 26.—PLUNKET undoubtedly the most successful Commissioner of Works of recent times. A little coolness sprung up between him and CAVENDISH BENTINCK about those staircases in Westminster Hall. But chacun a son idea of a staircase. PLUNKET quite as likely to be right as C.B. Always doing something to improve arrangements of House. Does it quietly, too; Members know nothing about it till they come down and find new Smoking-room, fresh arrangements of lights, new rooms for Ministers, and occasionally a priceless old table adorning Tea-room. Various accounts of its origin. Some say Magna Charta signed on it. Others fixing earlier date and attracted by the initials "W.R." clearly carved on left leg, affirm that it is the very table on which WILLIAM REX took his five o'clock tea after Battle of Hastings.

Latest surprise prepared by First Commissioner is illumination of entrance to House from Lobby, cunningly effected by electric lights set within recesses of arch. SCHNAD-HORST, revisiting House after long interval, astonished at this. "Making things very comfortable in anticipation of our coming in," he says, smiling sweetly.

Later came upon NICHOLAS WOODS; found him standing in attitude of patient and intelligent expectation. "What are you waiting there for?" I asked. "Why don't you come in and hear SWINBURNE make one or two speeches on Tithes Bill?"

[pg 72]"Well—er—fact is," said NICHOLAS, steadfastly keeping his eyes on archway, "WILFRID LAWSON told me that if I was here about eleven o'clock I would see PLUNKET and the ATTORNEY-GENERAL come out under the archway dancing a pas de deux. Couldn't make out when I arrived what the illumination was for; asked LAWSON. 'Oh' says he, 'it's the First Commissioner's reminiscence of one of the alcoves at Vauxhall Gardens.' Then he told me about PLUNKET and WEBSTER. Thought I'd like to see it. Do you think it's all right?"

"Well," I said, "ALBERT ROLLIT did tell me something about ATTORNEY-GENERAL going on the Spree. But that was in Germany, and he had his skates with him. Don't know how it'll be here. You mustn't forget that WILFRID's something of a wag. Wouldn't advise you to wait much after eleven o'clock."

House engaged all night on Tithes Bill. Not particularly lively. Towards midnight TANNER, preternaturally quiet since House met, suddenly woke up, and, à propos de bottes, moved to report progress. COURTNEY down on him like cartload of bricks; declined to put Motion, declaring it abuse of forms of House. This rather depressing. In good old times there would have been an outburst of indignation in Irish camp; Chairman's ruling challenged, and squabble agreeably occupied rest of evening. But times changed. No Irish present to back TANNER, who, with despairing look round, subsided, and business went forward without further check.

Business done.—Tithes Bill in Committee.

Tuesday.—Mr. DICK DE LISLE came down to House to-night full of high resolve. Hadn't yet been a Member of House when it shook from time to time with the roar of controversy round BRADLAUGH, his oath, his affirmation, and his stylographic pen. At that time was in Singapore, helping Sir FREDERICK WELD to govern the Straits Settlement. But had watched controversy closely, and had contributed to its settlement by writing a luminous treatise, entitled, The Parliamentary Oath. Now, by chance, the question cropped up again. BRADLAUGH had secured first place on to-night's order for his Motion rescinding famous Resolution of June, 1880, declaring him ineligible to take his seat. BRADLAUGH ill in bed; sick unto death, as it seemed; but HUNTER had taken up task for him, and would move Resolution. Of course the Government would oppose it; if necessary, DE LISLE would assist them with argument. In any case, they should have his vote. Heard SOLICITOR-GENERAL with keen satisfaction. He showed not only the undesirability and impossibility of acceding to proposition, but denounced it as "absolutely childish." Mr. G. followed; but Mr. G. said the same kind of things eleven years ago, when he was Leader of triumphant party, and had been defeated again and again. Of course same fate awaited him now. Government had spoken through mouth of SOLICITOR-GENERAL, and there was an end on't.

Not quite. STAFFORD NORTHCOTE, unaccustomed participant in debate, presented himself. Stood immediately behind OLD MORALITY, by way of testifying to his unaltered loyalty. At same time he suggested that, after all, would be as well to humour BRADLAUGH and his friends, and strike out Resolution. Then OLD MORALITY rose from side of SOLICITOR-GENERAL, and, unmindful of that eminent Lawyer's irresistible argument and uncompromising declaration, said, "on the whole," perhaps NORTHCOTE was right, and so mote it be.

The elect of Mid-Leicestershire gasped for air. Did his ears deceive him, or was this the end of the famous BRADLAUGH incidents? OLD MORALITY, in his cheerful way, suggested that, as they were doing the thing, they had better do it unanimously. General cheer approved. DE LISLE started to his feet. One voice, at least, should be heard in protest against this shameful surrender. Began in half-choked voice: evidently struggling against some strange temptation; talked about the Parnell Commission; accused House of legalising atheism, and whitewashing treason; argued at length with Mr. G. on doctrine of excess of jurisdiction. Observed, as he went on, to be waving his hands as if repelling some object; turned his head on one side as if he would fain escape apparition; House looked on wonderingly. At length, with something like subdued sob, DE LISLE gave way, and Members learned what had troubled him. It was dear old Mr. Dick's complaint. Standing up to present his Memorial against tergiversation of OLD MORALITY, DE LISLE could not help dragging in head of CHARLES THE FIRST. "As a Royalist," he said, "I should maintain that the House of Commons exceeded its jurisdiction when it ordered King CHARLES THE FIRST to be beheaded, but I never heard that it was proposed, after the Restoration, to expunge the Resolution from the books."

Irreverent House went off into roars of laughter, amid which Mr. Dick, more than ever bewildered, sat down, and presently went out to ask Miss Betsy Trottwood why they laughed.

Business done.—Resolution of June, 1880, declaring BRADLAUGH ineligible to sit, expunged from journals.

Thursday.—As OLD MORALITY finely says, "The worm persistently incommoded by inconvenient attentions will finally assume an aggressive attitude." So it has proved to-night. SYDNEY GEDGE long been object of contumelious attention. Members jeer at him when he rises; talk whilst he orates; laugh when he is serious, are serious when he is facetious. But the wounded worm has turned at last. SYDNEY has struck. GEDGE has been goaded once too often.

It was COURTNEY brought it about. Been six hours in Chair in Committee on Tithes Bill; feeling faint and weary, glad to refresh himself with sparkling conversation of Grand Young GARDNER; GEDGE on his feet at moment in favourite oratorial attitude; pulverising Amendment moved by GRAY; thought, as he proceeded, he heard another voice. Could it be? Yes; it was Chairman of Committees conversing with frivolous elderly young man whilst he (S.G.) was debating the Tithes Bill! Should he pass over this last indignity? No; honour of House must be vindicated; lofty standard of debate must be maintained; the higher the position of offender the more urgent his duty to strike a blow. Was standing at the moment aligned with Chair; paused in argument; faced about to the right and marched with solemn steps to the end of Gangway, the Bench having been desolated by his speech so far as it had gone.

"Sir," he said, bending angry brows on Chairman, "I am afraid my speech interrupted your conversation. Therefore I have moved further away."

That was all, but it was enough. HERBERT GARDNER slunk away, COURTNEY hastily turned over pages of the Bill; hung down his guilty head, and tried to look as if it were MILMAN who had been engaged in conversation. Now MILMAN was asleep.

Business done.—Level flow of Debate on Tithes Bill interrupted by revolt of SYDNEY GEDGE.

Friday.—Rather a disappointing evening from Opposition point of view. In advance, was expected to be brilliant field-night. Irish Administration to be attacked all along line; necessity for new departure demonstrated. SHAW-LEFEVRE led off with Resolution demanding establishment of Courts of Arbitration. Large muster of Members. Mr. G. in his place; expected to speak; but presently went off; others fell away, and all the running made from Ministerial Benches. SHAW-LEFEVRE roasted mercilessly. House roared at SAUNDERSON's description of his going to interview SULTAN, and being shown into stable to make acquaintance of SULTAN's horse. Prince ARTHUR turned on unhappy man full blast of withering scorn. Don't know whether SHAW-LEFEVRE felt it; some men rather be kicked than not noticed at all; but Liberals felt they had been drawn into ridiculous position, and murmured bad words. "What's the use," they ask, "of winning Hartlepool out of doors, if things are so managed that we are made ridiculous within?"

Business done.—SHAW-LEFEVRE's Resolution on Irish Land Question negatived by 213 Votes against 152.

Last Act—On the road to the Guillotine—Hero, instead of Heroine, about to be executed—Heroine imploring Hero to sign paper.

Heroine. Attach but your signature, and you are free!

Hero (after reading document in a tone of horror). What, a vow to marry, with the prospect of a breach of promise case to follow! Never! Death is preferable! [Exit to be guillotined. Curtain.

AN ARTIST AND A WHISTLER.—M. COQUELIN has summoned M. LISSAGARAY for having thrown a whistle at him on the night of the Thermidor row. It is to be hoped that by this time M. LISSAGARAY will have been made to pay for his whistle.

NOTICE.—Rejected Communications or Contributions, whether MS., Printed Matter, Drawings, or Pictures of any description, will in no case be returned, not even when accompanied by a Stamped and Addressed Envelope, Cover, or Wrapper. To this rule there will be no exception.