LITTLE BOY BLUE

The little toy dog is covered with

dust

But sturdy and stanch he

stands,

And the little toy soldier is red with rust

And his musket moulds in his

hands.

Time was when the little toy dog was new

And the soldier was passing

fair,

And that was the time when our Little Boy Blue

Kissed them and put them

there.

"Now, don't you go till I come,"

he said,

"And don't you

make any noise!"

So, toddling off to his trundle-bed,

He dreamt of the pretty toys.

And, as he was dreaming, an angel song

Awakened our Little Boy

Blue—

Oh! the years are many—the years are

long—

But the little toy

friends are true!

Aye, faithful to Little Boy Blue they

stand—

Each in the same

old place,

Awaiting the touch of a little hand,

The smile of a little face.

And they wonder—as waiting the long years through

In the dust of that little

chair—

What has become of our Little Boy Blue

Since he kissed them and put them

there.

| Chapter | Page | |

| I. | PEDIGREE | 1 |

| II. | INTRODUCTION TO COLORED INKS | 15 |

| III. | SOME LETTERS | 44 |

| IV. | MORE LETTERS | 71 |

| V. | PUBLICATION OF HIS FIRST BOOKS | 107 |

| VI. | HIS SECOND VISIT TO EUROPE | 138 |

| VII. | IN THE SAINTS' AND SINNERS' CORNER | 169 |

| VIII. | POLITICAL RELATIONS | 198 |

| IX. | HIS "AUTO-ANALYSIS" | 234 |

| X. | LAST YEARS | 261 |

| XI. | LAST DAYS | 297 |

| APPENDIX | 321 | |

| INDEX | 341 |

| ORIGINAL TEXT OF "LITTLE BOY BLUE" With drawings in colors by Eugene Field. |

Frontispiece |

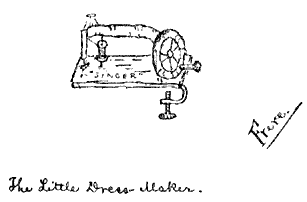

| THE LITTLE DRESS-MAKER From a drawing by Eugene Field. |

23 |

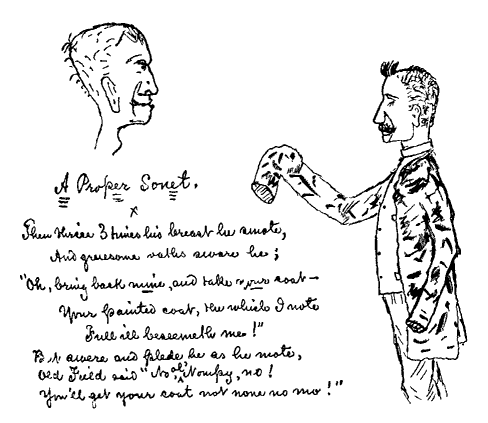

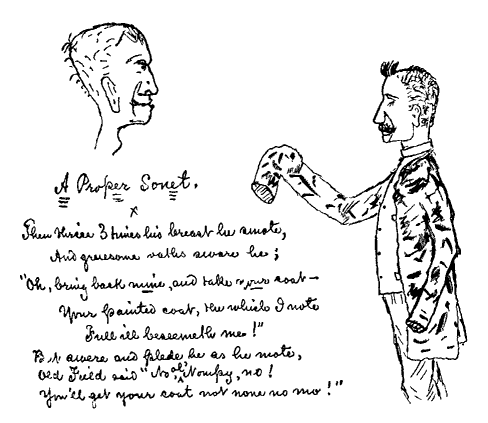

| A PROPER SONET From a drawing in colors by Eugene Field. |

26 |

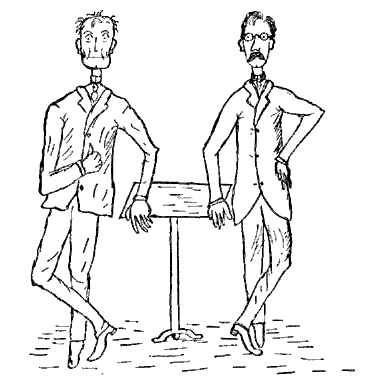

| FIELD AND BALLANTYNE AWAITING THE ARRIVAL OF A

BISCUIT FROM NEW BRUNSWICK From a drawing by Eugene Field. |

27 |

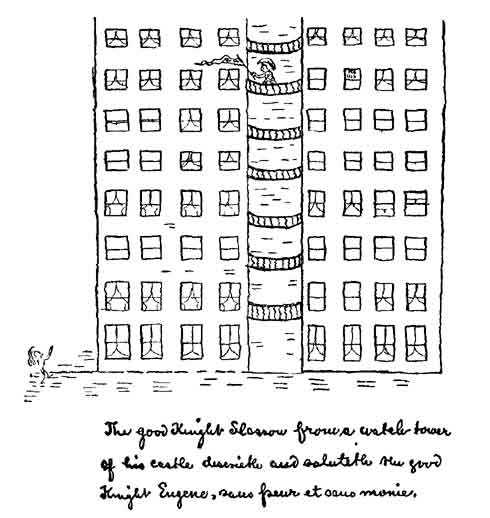

| THE GOOD KNIGHT SLOSSON'S CASTLE From a drawing by Eugene Field. |

29 |

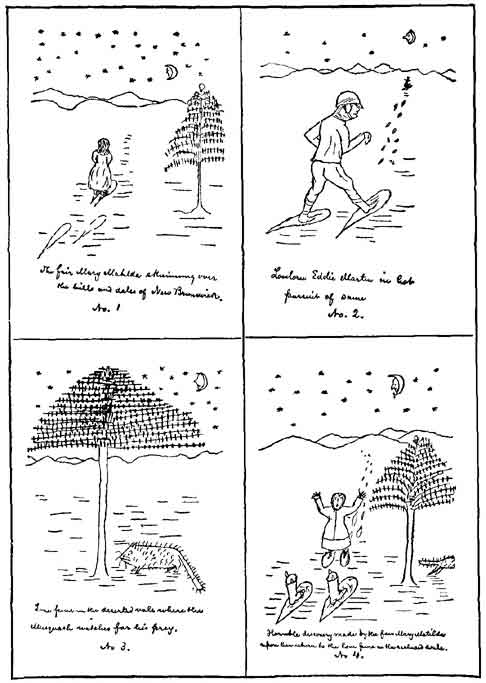

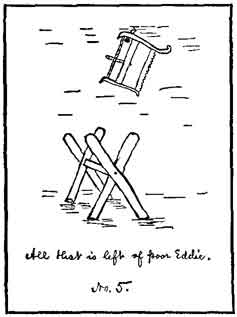

| A TRAGEDY IN FIVE ACTS From drawings by Eugene Field. |

30, 31 |

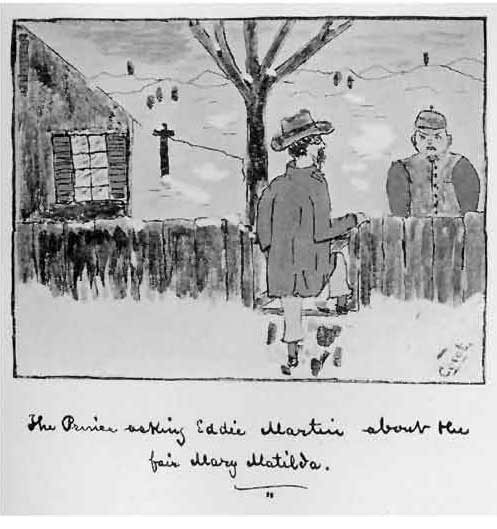

| HOW MARY MATILDA WON A PRINCE: From drawings by Eugene Field. |

|

| THE PRINCE ASKING EDDIE MARTIN ABOUT THE FAIR MARY MATILDA | 38 |

| THE PRINCE'S COAT-OF-ARMS— FLIGHT OF THE FAIR MARY MATILDA— THE AGGRAVATING MIRAGE |

40 |

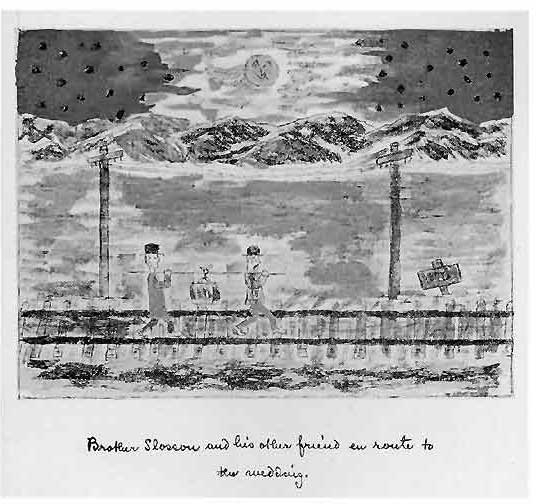

| BROTHER SLOSSON AND HIS OTHER FRIEND EN ROUTE TO THE WEDDING | 42 |

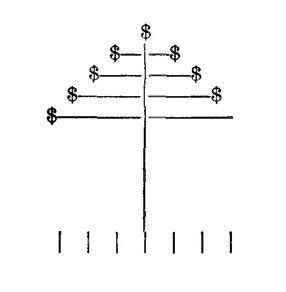

| A STAMP ACCOUNT | 57 |

| AN ECHO FROM MACKINAC ISLAND With drawings by Eugene Field. |

58 |

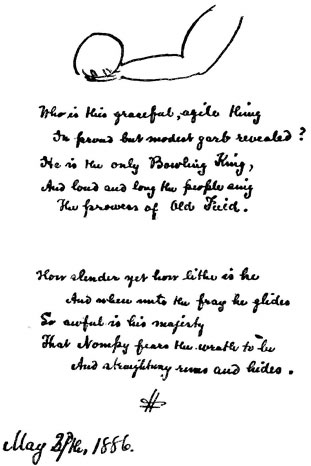

| A BOWLING CHALLENGE FROM EUGENE FIELD | 75 |

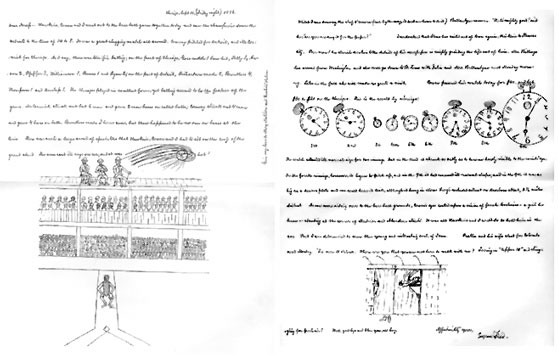

| A LETTER FROM EUGENE FIELD CONTAINING THREE DRAWINGS | 78 |

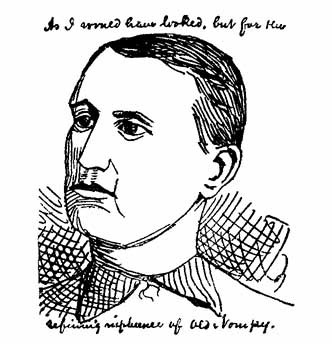

| FIELD'S PORTRAIT OF HIMSELF "As I would have looked but for the refining influence of Old Nompy." |

88 |

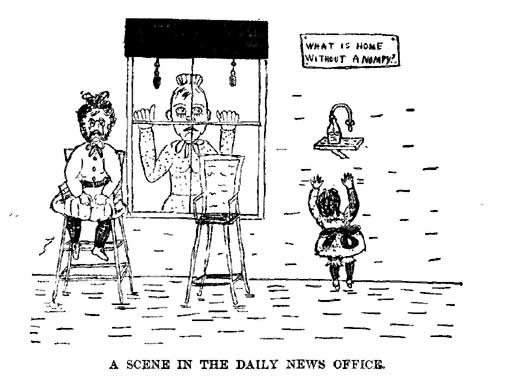

| A SCENE IN THE DAILY NEWS OFFICE From a drawing by Eugene Field. |

99 |

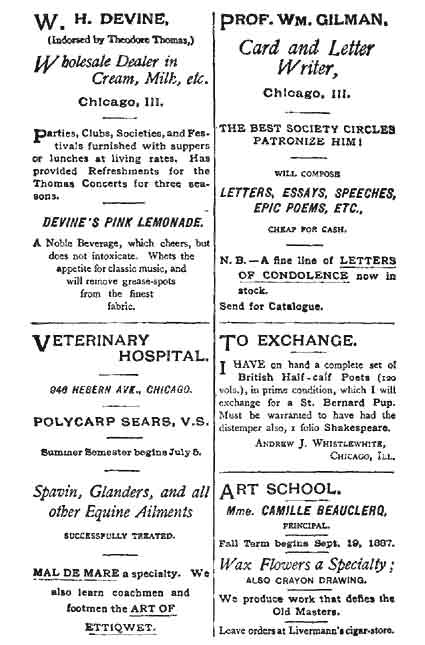

| PAGE OF ADVERTISEMENTS FROM "CULTURE'S GARDEN" | 111 |

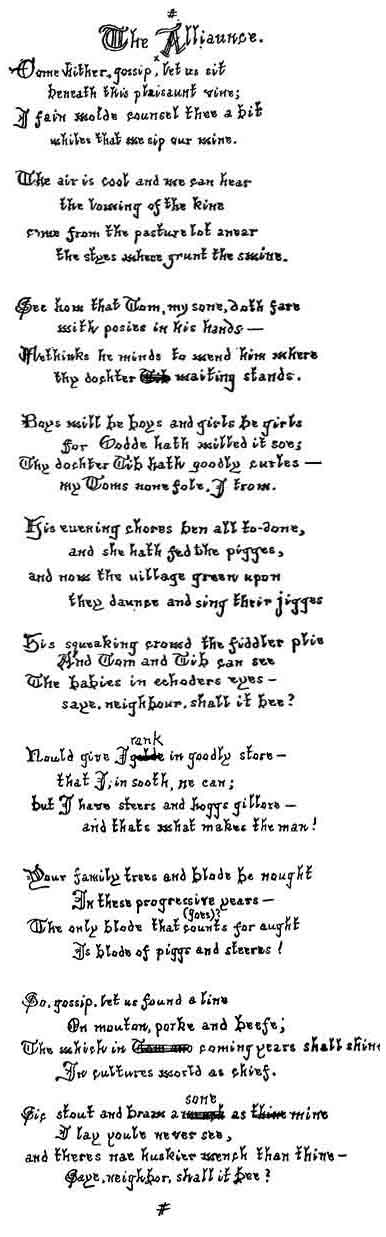

| "THE ALLIAUNCE" | 124 |

| SKETCH AND EPITAPH From a drawing by Eugene Field. |

168 |

| OFF TO SPRINGFIELD From a drawing by Eugene Field. |

201 |

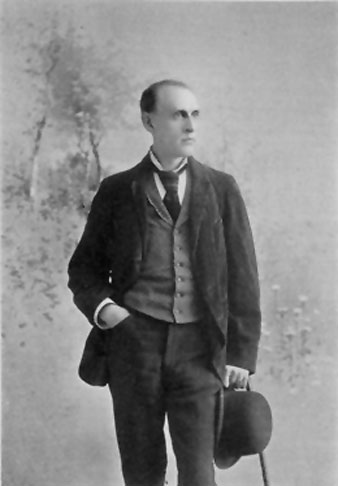

| ROSWELL FIELD | 142 |

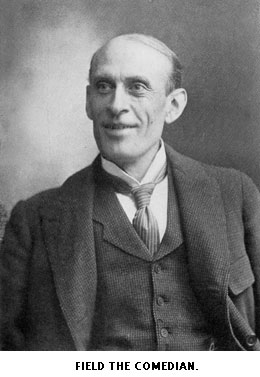

| FIELD THE COMEDIAN | 254 |

| EUGENE FIELD WITH HIS DUTCH RING | 302 |

CHAPTER I

OUR PERSONAL RELATIONS

In the loving "Memory" which his brother Roswell contributed to the "Sabine Edition" of Eugene Field's "Little Book of Western Verse," he says: "Comradeship was the indispensable factor in my brother's life. It was strong in his youth: it grew to be an imperative necessity in later life. In the theory that it is sometimes good to be alone he had little or no faith." From the time of Eugene's coming to Chicago until my marriage, in 1887, I was his closest comrade and almost constant companion. At the Daily News office, for a time, we shared the same room and then the adjoining rooms of which I have spoken. Field was known about the office as my "habit," a relationship which gave point to the touching appeal which served as introduction to the dearly cherished manuscript copy, in two volumes, of nearly one hundred of his poems, which was his wedding gift to Mrs. Thompson. It was entitled, in red ink, "Ye Piteous Complaynt of a Forsooken Habbit; a Proper Sonet," and reads:

Ye boone y aske is smalle indeede

Compared with what y once did seeke—

Soe, ladye, from yr. bounteous meede

Y pray you kyndly heere mee speke.

Still is yr. Slosson my supporte,

As once y was his soul's delite—

Holde hym not ever in yr. courte—

O lette me have hym pay-daye nite!

One nite per weeke is soothly not

Too oft to leese hym from yr. chaynes;

Thinke of my lorne impoverisht lotte

And eke my jelous panges and paynes;

Thinke of ye chekes y stille do owe—

Thinke of my quenchlesse appetite—

Thinke of my griffes and, thinking so,

Oh, lette me have hym pay-daye nite!

Along the border of this soulful appeal was engrossed, in a woful mixture of blue and purple inks: "Ye habbit maketh mone over hys sore griffe and mightylie beseacheth the ladye yt she graunt hym ye lone of her hoosband on a pay-daye nite."

Through those years of comradeship we were practically inseparable from the time he arrived at the office, an hour after me, until I bade him good-night at the street-car or at his own door, when, according to our pact, we walked and talked at his expense, instead of supping late at mine. The nature of this pact is related in the following verse, to which Field prefixed this note: "While this poem is printed in all the 'Reliques of Ye Good Knights' Poetrie,' and while the incident it narrates is thoroughly characteristic of that Knightly Sage, the versification is so different from that of the other ballads that there is little doubt that this fragment is spurious. Prof. Max Beeswanger (Book III., page 18, old English Poetry) says that these verses were written by Friar Terence, a learned monk of the Good Knight's time."

THE GOOD KNIGHT TO SIR SLOSSON

The night was warm as summer

And the wold was wet with dew,

And the moon rose fair,

And the autumn air

From the flowery prairies blew;

You took my arm, ol' Nompy,

And measured the lonely street,

And you said, "Let's walk

In the gloom and talk—

'Tis too pleasant to-night to eat!"

And you quoth: "Old Field supposin'

Hereafter we two agree;

If it's fair when we're through

I'm to walk with you—

If it's foul you're to eat with me!"

Then I clasped your hand, ol' Nompy,

And I said: "Well, be it so."

The night was so fine

I didn't opine

It could ever rain or snow!

But the change came on next morning

When the fickle mercury fell,

And since, that night

That was warm and bright

It's snowed or it's rained like—well.

Have you drawn your wages, Nompy?

Have you reckoned your pounds and pence?

Harsh blows the wind,

And I feel inclined

To banquet at your expense!

The "Friar Terence" of Field's note was the Edward J. McPhelim to whom reference has already been made, who often joined us in our after-theatre symposiums, but could not be induced to walk one block if there was a street-car going his way.

As bearing on the nature of these "banquets," and the unending source of enjoyment they were to both of us, the following may throw a passing light:

Discussing great and sumptuous cheer

At Boyle's one midnight dark and drear

Two gentle warriors sate;

Out spake old Field: "In sooth I reck

We bide too long this night on deck—

What, ho there, varlet, bring the check!

Egad, it groweth late!"

Then out spake Thompson flaming hot:

"Now, by my faith, I fancy not,

Old Field, this ribald jest;

Though you are wondrous fair and free

With riches that accrue to thee,

The check to-night shall come to me—

You are my honored guest!"

But with a dark forbidding frown

Field slowly pulled his visor down

And rose to go his way—

"Since this sweet favor is denied,

I'll feast no more with thee," he cried—

Then strode he through the portal wide

While Thompson paused to pay.

Speaking of "the riches that accrued" to Field it may be well to explain that when he came to Chicago from Denver he was burdened with debts, and although subsequently he was in receipt of a fair salary, it barely sufficed to meet his domestic expenses and left little to abate the importunity of the claims that followed him remorselessly. He lived very simply in a flat on the North Side—first on Chicago Avenue, something over a mile from the office, later on in another flat further north, on La Salle Avenue, and still later, and until he went to Europe, in a small rented house on Crilly Place, which is a few blocks west of the south end of Lincoln Park.

By arrangement with the business office, Field's salary was paid to Mrs. Field weekly, she having the management of the finances of the family. Field, Ballantyne, and I were the high-priced members of the News staff at that time, but our pay was not princely, and two of us were engaged in a constant conspiracy to jack it up to a level more nearly commensurate, as we "opined," with our respective needs and worth. The third member of the trio, who personally sympathized with our aspirations and acknowledged their justice, occupied an executive position, where he was expected to exercise the most rigorous economy. Moreover, he had a Scotsman's stern and brutal sense of his duty to get the best work for the least expenditure of his employer's money. It was not until Field and I learned that Messrs. Lawson & Stone were more appreciative of the value of our work that our salaries gradually rose above the level where Ballantyne would have condemned them to remain forever in the sacred name of economy.

I have said that Field's weekly salary—"stipend," he called it—was paid regularly to Mrs. Field. I should have said that she received all of it that the ingenious and impecunious Eugene had not managed to forestall. Not a week went by that he did not tax the fertility of his active brain to wheedle Collins Shackelford, the cashier, into breaking into his envelope for five or ten dollars in advance. These appeals came in every form that Field's fecundity could invent. When all other methods failed the presence of "Pinny" or "Melvin" in the office would afford a messenger and plan of action that was always crowned with success. "Pinny" especially seemed to enter into his father's schemes to move Shackelford's sympathy with the greatest success. He was also very effective in moving Mr. Stone to a consideration of Field's requests for higher pay.

In his "Eugene Field I Knew," Francis Wilson has preserved a number of these touching "notes" to Shackelford, in prose and verse, but none of them equals in the shrewd, seductive style, of which Field was master, the following, which was composed with becoming hilarity and presented with befitting solemnity:

A SONNET TO SHEKELSFORD

Sweet Shekelsford, the week is near its end,

And, as my custom is, I come to thee;

There is no other who has pelf to lend,

At least no pelf to lend to hapless me;

Nay, gentle Shekelsford, turn not away—

I must have wealth, for this is Saturday.

Ah, now thou smil'st a soft relenting smile—

Thy previous frown was but a passing joke,

I knew thy heart would melt with pity while

Thou heardst me pleading I was very broke.

Nay, ask me not if I've a note from Stone,

When I approach thee, O thou best of men!

I bring no notes, but, boldly and alone,

I woo sweet hope and strike thee for a ten.

December 3d, 1884.

There is no mistaking the touch of the author of "Mr. Billings of Louisville" in these lines, in which humor and flattery robbed the injunction of Mr. Stone against advancing anything on Field's salary of its binding force. Having once learned the key that would unlock the cashier's box, he never let a week go by without turning it to some profitable account. But it is only fair to say that he never abused his influence over Mr. Shackelford to lighten the weekly envelope by more than the "necessary V" or the "sorely needed X."

I have dwelt upon these conditions because they explain to some extent our relations, and why, after we had entered upon our study of early English ballads and the chronicles of knights and tourneys, Field always referred to himself as "the good but impecunious Knight, sans peur et sans monnaie," while I was "Sir Slosson," "Nompy," or "Grimesey," as the particular roguery he was up to suggested.

It was while I was visiting my family in the province of New Brunswick, in the fall of 1884, that I received the initial evidence of a particular line of attack in which Field delighted to show his friendship and of which he never wearied. It came in shape of an office postal card addressed in extenso, "For Mr. Alexander Slason Thompson, Fredericton, New Brunswick"—the employment of the baptismal "Alexander" being intended to give zest to the joke with the postal officials in my native town. The communication to which the attention of the curious was invited by its form read:

CHICAGO, October 6th, 1884.

GRIMESEY:

Come at once. We are starving! Come and bring your wallet with you.

EUGENE F——D.

JOHN F. B——E.

Of course the postmaster at Fredericton read the message, and I was soon conscious that a large part of the community was consumed with curiosity as to my relations with my starving correspondents.

But this served merely as a prelude to what was to follow. My visit was cut short by an assignment from the Daily News to visit various towns in Maine to interview the prominent men who had become interested, through James G. Blaine, in the Little Rock securities which played such a part in the presidential campaigns of 1876 and 1884. For ten days I roved all over the state, making my headquarters at the Hotel North, Augusta, where I was bombarded with postal cards from Field. They were all couched in ambiguous terms and were well calculated to impress the inquisitive hotel clerk with the impecuniosity of my friends and with the suspicion that I was in some way responsible for their desperate condition. Autograph hunters have long ago stripped me of most of these letters of discredit, but the following, which has escaped the importunity of collectors of Fieldiana, will indicate their general tenor:

CHICAGO, October 10th, 1884.

If you do not hasten back we shall starve. Harry Powers has come to our rescue several times, but is beginning to weaken, and the outlook is very dreary. If you cannot come yourself, please send certified check.

Yours hungrily,

E.F.

J.F.B.

The same postal importunities awaited me at the Parker House while in Boston, and came near spoiling the negotiations in which I was engaged, for the News, for the, till then, unpublished correspondence between Mr. Blaine and Mr. Fischer, of the Mulligan letters notoriety. My assignment as staff correspondent called for visits to New York, Albany, and Buffalo on my way home, and wherever I stopped I found proofs that Field was possessed of my itinerary and was bound that I should not escape his embarrassing attentions.

There is no need to tell that of all anniversaries of the year Christmas was the one that appealed most strongly to Eugene Field's heart and ever-youthful fancy. It was in his mind peculiarly the children's festival, and his books bear all the testimony that is needed, from the first poem he acknowledged, "Christmas Treasures," to the last word he wrote, that it filled his heart with rejoicings and love and good will. But there is an incident in our friendship which shows how he managed to weave in with the blessed spirit of Christmas the elfish, cheery spirit of his own.

We had spent Christmas Eve, 1884, together, and, as usual, had expended our last dime in providing small tokens of remembrance for everyone within the circle of our immediate friends. I parted from him at the midnight car, which he took for the North Side. Going to the Sherman House, I caught the last elevator for my room on the top floor, and it was not long ere I was oblivious to all sublunary things.

Before it was fairly light the next morning I was disturbed and finally awakened by the sound of voices and subdued tittering in the corridor outside my door. Then there came a knock, and I was told that there was a message for me. Opening the door, my eyes were greeted with a huge home-knit stocking tacked to it with a two-pronged fork and filled with a collection of conventional presents for a boy—a fair idea of which the reader can glean from the following lines in Field's handwriting dangling from the toe:

I prithee, gentle traveller, pause

And view the work of Santa Claus.

Behold this sock that's brimming o'er

With good things near our Slason's door;

Before he went to bed last night

He paddled out in robe of white,

And hung this sock upon the wall

Prepared for Santa Claus's call.

And said, "Come, Santa Claus, and bring

Some truck to fill this empty thing."

Then back he went and locked the door,

And soon was lost in dream and snore.

The Saint arrived at half-past one—

Behold how well his work is done:

See what a wealth of food and toy

He brought unto the sleeping boy:

An apple, fig, and orange, too,

A jumping-jack of carmine hue,

A book, some candy, and a cat,

Two athletes in a wrestling spat,

A nervous monkey on a stick,

And honey cake that's hard and thick.

Oh, what a wealth of joy is here

To thrill the soul of Slason dear!

Touch not a thing, but leave them all

Within this sock upon the wall;

So when he wakes and comes, he may

Find all these toys and trinkets gay,

And thank old Santa that he came

Up all these stairs with all this game.

If I have succeeded in conveying any true impression of Eugene Field's nature, the reader can imagine the pleasure he derived from this game, in planning it, in providing the old-fashioned sock, toys, and eatables, and in toiling up six flights of stairs after he knew I was asleep, to see that everything was arranged so as to attract the attention of the passing traveller. The success of his game was fully reported to him by his friend, the night clerk—now one of the best known hotel managers in Chicago—and mightily he enjoyed the report that I had been routed out by the early wayfarer before the light of Christmas broke upon the slumbering city.

CHAPTER II

INTRODUCTION TO COLORED INKS

My room in the Sherman House, then, as now, one of the most conveniently located hotels in the business district of Chicago, was the scene of Eugene Field's first introduction to the use of colored inks. His exquisitely neat, small, and beautifully legible handwriting has always been the subject of wondering comment and admiration. He adopted and perfected that style of chirography deliberately to reduce the labor of writing to a minimum. And he succeeded, for few pen-men could exceed him in the rapidity with which he produced "copy" for the printer and none excelled him in sending that copy to the compositor in a form so free from error as to leave no question where blame for typographical blunders lay. In over twenty years' experience in handling copy I have only known one regular writer for the press who wrote as many words to a sheet as Field. That was David H. Mason, the tariff expert, whose handwriting was habitually so infinitesimal that he put more than a column of brevier type matter on a single page, note-paper size.

Strange to say, the compositors did not complain of this eye-straining copy, which attracted them by its compactness and stretched out to nearly half a column in the "strings" by which their pay was measured. From this it may be inferred that there was never any complaint of Field's manuscript from the most exacting and captious of all newspaper departments—the composing room.

However, I set out to relate the genesis of Field's use of the colored inks, with which he not only embellished his correspondence and presentation copies of his verse, but with which he was wont to illuminate his copy for the printer. It came about in this way:

In the winter of 1885 Walter Cranston Larned, author of the "Churches and Castles of Mediæval France," then the art critic for the News, contributed to it a series of papers on the Walters gallery in Baltimore. These attracted no small attention at the time, and were the subject of animated discussion in art circles in Chicago. They were twelve in number, and ran along on the editorial page of the News from February 23d till March 10th. At first we of the editorial staff took only a passing interest in Mr. Larned's contributions. But one day Field, Ballantyne, and I, from a discussion of the general value of art criticism in a daily newspaper, were led to question whether it conveyed an intelligible impression of the subject, and more particularly of the paintings commented on, to the ordinary reader. The point was raised as to the practicability of artists themselves reproducing any recognizable approach to the original paintings by following Mr. Larned's verbal descriptions. Thereupon we deliberately set about, in a spirit of frolic to be sure, to attempt what we each and all considered a highly improbable feat.

Armed with the best water colors we could find in Abbott's art store, we converted my bachelor quarters in the Sherman House into an amateur studio, where we daily labored for an hour or so in producing most remarkable counterfeits of the masterpieces in Mr. Walters's gallery as seen through Mr. Larned's text. We were innocent of the first principles of drawing and knew absolutely nothing about the most rudimentary use of water colors. Somehow, Field made a worse botch in mixing and applying the colors than did either Ballantyne or I. They would never produce the effects intended. He made the most whimsical drawings, only to obliterate every semblance to his original conception in the coloring. To prevent his going on a strike, I ransacked Chicago for colored inks to match those required in the pictures that had been assigned to him. This inspired him with renewed enthusiasm, and he devoted himself to the task of realizing Mr. Larned's descriptions in colored inks with the zest that produces the masterpieces over which artists and critics rave.

His first work in this line was a reproduction—or shall I call it a restoration—of Corot's "St. Sebastian." In speaking of this as one of the noteworthy paintings in the Walters gallery, Mr. Larned had said that it was a landscape in which the figures were quite subordinate and seemed merely intended to illustrate the deeper meaning of the painter in his rendition of nature. According to the critic's detailed description, it was a forest scene. "Great trees rise on the right to the top of the canvas. On the left are also some smaller trees, whose upper branches reach across and make, with the trees on the right, a sort of arch through which is seen a wonderful stretch of sky. A rocky path leads away from the foreground beneath the overhanging trees, sloping upward until it reaches the crest of a hill beneath the sky. Just at this point the figures of two retreating horsemen are seen. These are the men who have been trying to kill St. Sebastian, and have left him, as they thought, dead in the depth of the forest. In the immediate foreground lies the figure of the half dead saint, whose wounds are being dressed by two women. Hovering immediately above this group, far up among the tree branches, two lovely little angels are seen holding the palm and crown of the martyr. All the figures are better painted than is usual with Corot, and the angels are very light and delicate, both in color and form." Mr. Earned quoted from a celebrated French authority that this was "the most sincerely religious picture of the nineteenth century." I leave it to the reader if Mr. Larned's description conveys any such impression. To Field's mind, it only suggested the grotesque, and his reproduction was a chef d'oeuvre, as he was wont to say. He followed the general outline of the scene as described above, but made the landscape subordinate to the figures. The retreating ruffians bore an unmistakable resemblance to outlawed American cowboys. The saint showed carmine ink traces of having been most shamefully abused. But the chief interest in the picture was divided between a lunch-basket in the foreground, from which protruded a bottle of "St. Jacob's" oil, and a brace of vividly pink cupids hopping about in the tree-tops, rejoicing over the magical effect of the saintly patent medicine. His treatment of this picture proved, if it proved anything, that Corot had gone dangerously near the line where the sublime suggests the ridiculous.

In Fortuny's "Don Quixote" Field found a subject that tickled his fancy and lent itself to his untrammelled sense of the absurd. According to Mr. Larned, Fortuny's picture—a water-color—in the Walters gallery was one which represents the immortal knight in the somewhat undignified occupation of searching for fleas in his clothing. He has thrown off his doublet and his under garment is rolled down to his waist, leaving the upper portion of his body nude, excepting the immense helmet which hides his bent-down head. Both hands grasp the under garment, and the eyes are evidently turned in eager expectancy upon the folds which the hands are clasping, in the hope that the roving tormentor has at last been captured. "What an astonishing freak of genius!" exclaimed Mr. Larned. "For genius it certainly is. The color and the drawing of the figure are simply masterly, and the entire tone of the picture is wonderfully rich; indeed, for a water-color, it is quite marvellous. This is one of Fortuny's celebrated pictures, but how the 'École des Beaux Arts' would in the old days have held up its hands and closed its eyes in holy horror! Possibly an earnest disciple of Lessing, even, might have a rather dubious feeling about such a choice of subjects."

But it suited Field's pen and colored inks to a T. He entered into Fortuny's spirit as far as he dared to go and helped it over the edge of the merely dubious to the unmistakably safe grotesque. His own Don Quixote was clad in modern costume, from the riding-boots and monster spurs up to the belt. From that point his emaciated body—a fearfully and wonderfully articulated semi-skeleton—was nude save for one or two sporadic hairs. In the place of the traditional helmet, the Don's head was encased in a garden watering-pot, on the spout of which, and dominating the entire canvas, as artists say, poised on one foot and evidently enjoying the sorrowful knight's discomfiture, was the pestiferous pulex irritans.

In the Walters gallery were several pictures of child-life by Frère, in which, according to Mr. Lamed, "every little figure is full of character"—a fact about which there is no doubt in the accompanying reproduction of Frère's "The Little Dressmaker," which by some chance was preserved from those "artist days."

The completed results of our many off-hours of artist life were bound in a volume which was presented to Mr. Larned at a formal lunch given in his honor at the Sherman House. The speech of presentation was made by our friend, "Colonel" James S. Norton, in what the rural paragrapher would have described as "the most felicitous effort of his life," and the wonderful collection was commended to Mr. Larned's grateful preservation by the judgment of Mr. Henry Field, whose own choice selection of paintings is the most valued possession of the Chicago Art Institute. Mr. Field testified that he recognized everyone of the amazing reproductions from their resemblance, grotesque in the main, to the originals in the Walters gallery, with which he was familiar.

It was for this occasion that Field composed and recited his remarkable German poem, entitled "Der Niebelrungen und der Schlabbergasterfeldt." From the manuscript copy in my scrap-book I give the original version of this extraordinary production, which was copied in the Illinois Staats Zeitung and went the rounds of the German press in all the dignity of German text and with a variety of serious criticisms truly comical:

DER NIEBELRUNGEN UND DER

SCHLABBERGASTERFELDT

(Narratively)

Ein Niebelrungen schlossen gold

Gehabt gehaben Richter weiss

Ein Schlabbergasterfeldt un Sold

Gehaben Meister treulich heiss

"Ich dich! Ich dich!" die Maedchein tzwei

"Ich dich!" das Niebelrungen drei.

(Tragically)

Die Turnverein ist lieb und dicht

Zum Fest und lieben kleiner Geld,

Der Niebelrungen picht ein Bricht—

Und hitt das Schlabbergasterfeldt!

"Ich dich! Ich dich!" die Maedchein schreit

Und so das Schlabbergaster deit!

(Plaintively)

Ach! weh das Niebelrungen spott

Ach! weh das Maedchein Turnverein

Und unser Meister lieben Gott—

Ach! weh das Weinerwurst und Wein!

Ach! weh das Bricht zum kleiner Geld—

Ach! weh das Schlabbergasterfeldt!

Ever after this Walters gallery incident it was my duty, so he thought, to keep Field's desk supplied with inks, not only of every color of the rainbow, but with lake-white, gold, silver, and bronze, and any other kind which his whim deemed necessary to give eccentric emphasis to some line, word or letter in whatever he chanced to be composing. His peremptory requests were generally preferred in writing, addressed "For the Lusty Knight, Sir Slosson Thompson, Office," and delivered by his grinning minion, the office factotum. Sometimes they were in verse, as in the following:

"Who spilt my bottle of ink?" said Field,

"Who spilt my bottle of ink?"

And then with a sigh, said Thompson, "'Twas I—

I broke that bottle of ink,

I think,

And wasted the beautiful ink."

"Who'll buy a bottle of ink?" asked Field,

"Who'll buy a bottle of ink?"

With a still deeper sigh his friend replied, "I—

I'll buy a bottle of ink

With chink,

I'll buy a bottle of ink!"

"Oh, isn't this beautiful ink!" cried Field,

"Beautiful bilious ink!"

He shook the hand of his old friend, and

He tipped him a pleasant wink,

And a blink,

As he went to using that ink.

While Field insisted on a variegated assortment of inks he did not demand a separate pen for each color. In lieu of these he possessed himself of an old linen office coat, which he donned when it was cool enough for a coat and used for a pen-wiper. When the temperature rendered anything beyond shirt-sleeves superfluous, this linen affair was hung so conveniently that he could still use it for what he regarded as its primary use. In warm weather I wore a presentably clean counterpart of Field's Joseph's coat of many colors. As often as necessary this went to the laundry. One day when it had just returned from one of these periodical visits, I was startled, but not surprised, to find that Field had appropriated my spotless linen duster to his own inky uses and left his own impossible creation hanging on my hook in its stead. Field's version of what then occurred is beautifully, if not truthfully, portrayed in the accompanying "Proper Sonet" and life-like portraits.

Then Kriee 3 times his breast he smote,

And gruesome oaths swore he;

Oh, bring back mine, and take your coat—

Your painted coat, the which I note

Full ill besemmeth me!"

But swere and plede he as he mote,

Old Field said "No, ol' Nompy, no!

You'll get your coat not none no mo!"

If the reader will imagine each mark on the coat, of which "Nompy" bootlessly complains, done in different colors, he will have some idea of the infinite pains Field bestowed on the details of his epistolary pranks.

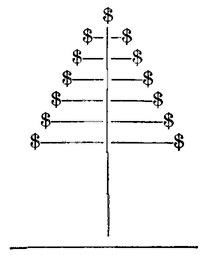

Out of the remarkable series of postal appeals which Field sent to me when I was visiting in New Brunswick grew an animated correspondence between Field and my youngest sister. She bore the good old-fashioned Christian names of Mary Matilda—a combination that struck a responsive chord in Field's taste in nomenclature, while his "come at once, we are starving" aroused her sense of humor to the point of forwarding an enormous raised biscuit two thousand miles for the relief of two Chicago sufferers. The result was an exchange of letters, one of which has a direct bearing on his whimsical adoption of many-colored inks in his writing. It read as follows:

CHICAGO, May the 7th, 1885.

Dear Miss:

I make bold to send herewith a diagram of the new rooms in which your brother Slason is now ensconced. The drawing may be bad and the perspective may be out of plumb, but the motif is good, as you will allow. All that Brother Slason needs now to symmetrize his new abode is a box from home—a box filled with those toothsome goodies which only a kind, loving, indulgent sister can make and donate to an absent brother. Having completed my contribution to the Larned gallery, and having exhibited the pictures in the recent salon, I have a large supply of colored inks on hand, which fact accounts for that appearance of an Easter necktie or a crazy quilt which this note has. In a few days I shall take the liberty of sending you the third volume of the "Aunt Mary Matilda" series—a tale of unusual power and interest. With many reverential obeisances and respectful assurances of regard, I beg to remain,

Your obedient servant,

EUGENE FIELD,

per

William Smith,

Secretary.

This epistle did indeed look like a crazy quilt. There was a change of color at the beginning of each line, as I have endeavored to indicate. It is beautifully written and in many respects besides its variegated aspect is the most perfect specimen of Field's painstaking epistolary handiwork I know of.

The "diagram of Mr. Slason Thompson's New Rooms" accompanying this letter was entirely worthy of it, and must have afforded him hours of boyish pleasure. No description can do it justice. He gave a ground plan of two square rooms with the windows marked in red ink, the doors in green, the bed, with a little figure on it, in blue, the fireplace in yellow, chairs and tables in purple, and the "buttery," as he insisted on calling the bathroom, in brown. As these apartments were in the Pullman Building, on the corner of Michigan Avenue and Adams Street, and commanded a glimpse of the lake, Field's diagram included a representation of Lake Michigan by zigzag lines of blue ink, with a single fish as long as a street-car, according to his scale, leering at the spectator from the billowy depths of indigo blue. Everything in the diagram was carefully identified in the key which accompanied it. An idea of the infinite attention to detail Field bestowed on such frivoling as this may be gathered from the accompanying cut of the Pullman Building, from the seventh story of which I am shown waving a welcome to the good but "impecunious knight." The inscription, in Field's handwriting, tells the story.

The good knight Slosson from a watch tower

of his castle desenith and salutith the good

Knight Eugene, sans peur et sans monie.

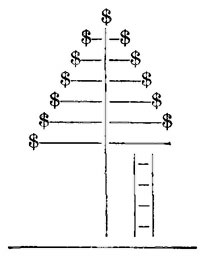

Early in the spring of 1885 Field was inspired, by an account I gave him of a snow-shoeing party my sister had described in one of her letters, to compose the series of pen-and-ink tableaux reproduced on pages 30 and 31.

A TRAGEDY IN FIVE ACTS.

From drawings by Eugene Field.

No. 1—The fair Mary Matilda skimming over the hills and dales of New Brunswick.

No. 2—Lovelorn Eddie Martin in hot pursuit of same.

No. 3—Lone pine in the deserted vale where the musquash watches for his prey.

No. 4—Horrible discovery made by the fair Mary Matilda upon her return to the lone pine in the secluded vale.

No. 5—All that is left of poor Eddie.

An inkling as to the meaning of these weird pictures may be gleaned from the letter I sent along with them to my sister, in which I wrote:

I was telling Field the story of your last snow-shoeing party when he was prompted to the enclosed tragedy in five acts. He hopes that you will not mistake the stars for mosquitoes, nor fail to comprehend the terrible fate that has overtaken Eddy Martin at the mouth of the voracious musquash, whose retreating tail speaks so eloquently of his toothsome repast. The lone pine tree is a thing that you will enjoy; also the expression of horror on your own face when you behold the empty boots of Eddy. There is a tragedy too deep for tears in the silent monuments of Field's ignorance of moccasins.

In explanation of the final scene in this "sad, eventful history" it should be said that "poor Eddie" was a harmless, half-witted giant who sawed the cord wood and did odd chores about my father's place. This gives significance to the pendant buck-saw and the lonely wood-horse. His lance rusts upon the wall and his steed stands silent in the stall. The reader should not pass from these examples of Field's humor with pen and ink without marking the changes that come across the face of the moon as the tragedy unfolds.

That Field found a congenial spirit and correspondent in my sister is further evidenced in the following letter written in gamboge brown:

CHICAGO, July the 2d, 1885.

Dear Miss:

In order that you may no longer groan under the erroneous impression which you appear to harbor, touching my physique, I remit to you a photograph of a majority of myself. The photograph was made last December, when I was, so to speak, at my perihelion in the matter of avoirdupois. You may be gratified to know that I have not shrunken much since that time. I have taken the timely precaution to label the picture in order that none of your Fredericton people thumbing over your domestic album shall mistake me for either a young Episcopal rector or a rising young negro minstrel.

The several drawings and paintings I have sent you ever and anon at your brother's expense are really not the best samples of my art. Mr. Walter Cranston Larned, a wealthy young tennis player of this city, has most of my chef d'oeuvres in his private gallery. I hope to be able to paint you a landscape in oil very soon. There is no sacrifice I would not be willing to make for one whom I esteem so highly as I do you. It might be just as well not to read this line to the old folks. Your brother Slosson has recently developed an insatiate passion for horse racing, and in consequence of his losses at pools I find him less prone to regale me with sumptuous cheer than he was before the racing season broke out. The prince, too, has blossomed out as a patron of the track, and I am slowly becoming more and more aware that this is a bitter world. I think I may safely say that I look wholly to such noble, generous young women as you and your sisters to preserve in me a consciousness that there is in life such a boon as generosity.

You will observe (if you have any eye for color) that I pen you these lines in gamboge brown; this is because Fourth of July is so near at hand. This side of the line we are fairly reeking with patriotism just now; even that mugwump-alien—your brother—contemplates celebrating in a fitting manner the anniversary of our country's independence of British Tyranny!

Will you please slap Bessie for me—the pert minx! I heard of her remarks about my story of Mary Matilda and the Prince.

Believe me as ever,

Sincerely yours,

EUGENE FIELD.

The story of "How Mary Matilda Won a Prince" was the third in what Field called his "Aunt Mary Matilda Series." The first of these was "The Lonesome Little Shoe" (see "The Holy Cross and Other Tales" of his collected works), which, after it was printed in the Morning News, was cut out and pasted in a little brown manila pamphlet, with marginal illustrations of the most fantastic nature. The title page of this precious specimen of Fieldiana is characteristic:

THE LONESOME LITTLE SHOE:

BEING

A WONDERFUL NARRATIVE CULLED FROM

THE

POSTHUMOUS PAPERS OF EUGENE FIELD

1885.

PROFUSELY ILLUSTRATED

DEDICATED TO AUNT MARY MATILDA'S PRESENT

AND FUTURE NEPHEWS AND NIECES,

THEIR HEIRS, ASSIGNS

AND ASSIGNEES

FOREVER

CANADIAN TRACT SOCIETY

(COPYRIGHT)

What became of the second of this wonderful series no one knows. The third, "How Mary Won a Prince," is the only instance that has come under my notice where Field put any of his compositions in typewriter. This was done to make the first edition consist of a single copy. The prince and hero of this romantic tale was our associate, John F. Ballantyne, and the story itself was "Inscribed to the beautiful, accomplished, amiable and ever-to-be-revered, Miss Mary Matilda Thompson, of Frederickton, York County, New Brunswick, Dominion of Canada, 1885." It was said to be "elegantly illustrated," of which the reader may judge from the accompanying reproductions.

HOW MARY MATILDA WON A PRINCE.

A gypsy had told Mary Matilda that she would marry a prince. This was when Mary Matilda was a little girl. She had given the gypsy a nice, fresh bun, and the gypsy was so grateful that she said she would tell the little girl's fortune, so Mary Matilda held out her hand and the old gypsy looked at it very closely.

"You are very generous," said the gypsy, "and your generosity will cause a prince to fall in love with you; the prince will rescue you from a great danger and you will wed the prince."

Having uttered these strange words, the gypsy went away and shortly after was sentenced to ten years in the penitentiary for having robbed a hen-roost.

Mary Matilda grew from childhood to be the most beautiful maiden in all the province; none was so beautiful and so witty as she. Withal she was so amiable and benevolent that all loved her, even those who envied her the transcendent charms with which she was endowed. As the unfortunate gypsy had predicted, Mary Matilda was the most generous maiden on earth and the fame of her goodness was wide-spread.

Now Mary Matilda had an older brother who had gone to a far-off country to become rich, and to accomplish those great political reforms to which his ambition inclined him. His name was Slosson, and in the far-off country he fell in with two young men of his own age who were of similar ambition. But they were even poorer than Slosson, and what particularly grieved them was the fact that their lineage was obscured by dark clouds of doubt. That is to say, they were unable to determine with any degree of positiveness whether they were of noble extraction; their parents refused to inform them, and consequently they were deeply distressed, as you can well imagine. Slosson was much charmed with their handsome bearing, chivalric ways, and honorable aspirations, and his pity was evoked by their poverty and their frequent sufferings for the very requirements of life. Freely he shared his little all with them, in return for which they gave him their gratitude and affection. One day Slosson wrote a letter to his sister Mary Matilda, saying: "A hard winter is coming on and our store of provisions is nearly exhausted. My two friends are in much distress and so am I. We have accomplished a political revolution, but under the civil service laws we can hardly expect an office."

Mary Matilda was profoundly touched by this letter. Her tender heart bled whenever she thought of her absent brother, and instinctively her sympathies went out toward his two companions in distress. So in her own quiet, maidenly way she set about devising a means for the relief of the unfortunate young men. She made a cake, a beautiful cake stuffed with plums and ornamented with a lovely design representing the lost Pleiad, which you perhaps know was a young lady who lived long ago and acquired eternal fame by dropping out of the procession and never getting back again. Well, Mary Matilda put this delicious cake in a beautiful paper collar-box and sent it in all haste to her brother and his two friends in the far-off country. Great was Slosson's joy upon receiving this palatable boon, and great was the joy of his two friends, who it must be confessed were on the very brink of starvation. The messages Mary Matilda received from the grateful young men, who owed their rescue to her, must have pleased her, although the consciousness of a noble deed is better than words of praise.

But one day Mary Matilda got another letter from her brother Slosson which plunged her into profound melancholy. "Weep with me, dear Sister," he wrote, "for one of my companions, Juan, has left me. He was the youngest, and I fear some great misfortune has befallen him, for he was ever brooding over the mystery of his lineage. Yesterday he left us and we have not seen him since. He took my lavender trousers with him."

As you may easily suppose, Mary Matilda was much cast down by this fell intelligence. She drooped like a blighted lily and wept.

"What can ail our Mary Matilda?" queried her mother. "The roses have vanished from her cheeks, the fire has gone out of her orbs, and her step has lost its old-time cunning. I am much worried about her."

They all noticed her changed appearance. Even Eddie Martin, the herculean wood-sawyer, observed the dejection with which the sorrow-stricken maiden emerged from the house and handed him his noontide rations of nutcakes and buttermilk. But Mary Matilda spoke of the causes of her woe to none of them. In silence she brooded over the mystery of Juan's disappearance.

When the winter came and the soft, fair snow lay ten or twelve feet deep on the level on the forest and stream, on wold and woodland, little Bessie once asked Mary Matilda if she would not take her out for a walk. Now little Bessie was Mary Matilda's niece, and she was such a sweet little girl that Mary Matilda could never say "no" to anything she asked.

"Yes, Bessie," said Mary Matilda, "if you will bundle up nice and warm I will take you out for a short walk of twenty or thirty miles."

So Bessie bundled up nice and warm. Then Mary Matilda went out on the porch and launched her two snow-shoes and got into them and harnessed them to her tiny feet.

"Where are you going?" asked Eddie Martin, pausing in his work and leaning his saw against a slab of green maple.

"I am going to take Bessie out for a short walk," replied Mary Matilda.

"Are you not afraid to go alone?" said Eddie Martin. "You know the musquashes are very thick, and this spell of winter weather has made them very hungry and ferocious."

"No, I am not afraid of the musquashes," replied Mary Matilda. But she was afraid of them: only she did not want to tell Eddie Martin so, for fear he would want to go with her. This was the first and only wrong story Mary Matilda ever told.

Having grasped little Bessie by the hand, Mary Matilda stepped over the fence and was soon lost to view. Scarcely had she gone when a tall, thin, haggard looking young man came down the street and leaned over the back gate.

"Can you tell me," he asked in weary tones, "whether the beautiful Mary Matilda abides hereabouts?"

"She lives here," replied Eddie Martin, "but she has gone for a walk with little Bessie."

"Whither did they drift?" queried the mysterious unknown.

"They started toward the Nashwaaksis," said Eddie Martin. "And I sadly fear the deadly musquash will pursue them."

The stranger turned pale and trembled at the suggestion.

"Will you lend me your saw for a brief period?" he asked.

"Why?" inquired Eddie Martin.

"To rescue the fair Mary Matilda from the musquashes," replied the stranger. Then he seized the saw, and with pale face started in the direction Mary Matilda had gone.

Meanwhile Mary Matilda had crossed the Nashwaaksis and was speeding in a southerly course toward the Nashwaak. The gentle breeze favored her progress, and as she sailed along, the snow danced like frozen feathers around her.

"Oh, how nice!" cried little Bessie.

"Yes, this clear, fresh, cold air gives one new life," said Mary Matilda.

They now came to the Nashwaak, on the farther bank of which were crouched a pack of hungry musquashes eagerly awaiting the approach of Mary Matilda and little Bessie.

"Hush," whispered the old big musquash. "Make no noise or they will hear us and make good their escape." But just then another musquash carelessly trod on the big musquash's tail and the old musquash roared with pain.

"What was that?" cried little Bessie.

Mary Matilda had heard the strange cry. She paused to listen. Then she saw the pack of musquashes in the snow on the farthest bank of the Nashwaak. Oh, how frightened she was! but with a shrill cry she seized Bessie in her arms, and, turning swiftly about, fled in the direction of McLeod hill. The musquashes saw her retreating, and with a howl of commingled rage and disappointment they started in hot pursuit. They ran like mad, as only starving musquashes can run. Every moment they gained on the maiden and her human charge until at last they were at her very heels. Mary Matilda remembered she had some beechnuts in her pocket. She reached down, grasped a handful of the succulent fruit and cast it to her insatiate pursuers. It stayed their pursuit for a moment, but in another moment they were on her track again, howling demoniacally. Another handful of the beechnuts went to the ravenous horde, and still another. By this time Mary Matilda had reached McLeod hill and was crossing the Nashwaaksis. Her imagination pictured a scuttled brigantine lying in the frozen stream. On its slippery deck stood a pirate, waving a gory cutlass.

"Ha, ha, ho, ho!" laughed the gory and bearded pirate.

"Save me!" cried Mary Matilda. "My beechnuts are all gone!"

"Throw them the baby!" answered the bearded pirate, "and save yourself! Ha, ha, ho, ho!"

Should she do it? Should she throw little Bessie to the devouring musquashes? No, she could not stoop to that ungenerous deed.

"No, base pirate!" she cried. "I would not so demean myself!"

But the scuttled brigantine had disappeared. Mary Matilda saw it was a mirage. Meanwhile the musquashes gained on her. The beechnuts had whetted their appetite. It seemed as if they were sure of their prey. But all at once they stopped, and Mary Matilda stopped, too. They were confronted by a haggard but manly form. It was the mysterious young stranger, and he had a saw which Eddie Martin had lent him. His aspect was so terrible that the musquashes turned to flee, but they were too late. The mysterious stranger laid about him so vigorously with his saw that the musquashes soon were in bits. Here was a tail, there a leg; here an ear, there a nose—oh, it was a rare potpourri, I can tell you! Finally the musquashes all were dead.

"To whom am I indebted for my salvation?" inquired Mary Matilda, blushing deeply.

"Alas, I do not know," replied the wan stranger. "I am called Juan, but my lineage is enveloped in gloom."

At once Mary Matilda suspected he was her brother's missing friend, and this suspicion was confirmed by the lavender trousers he wore. She questioned him closely, and he told her all. Bessie heard all he said, and she could tell you more particularly than I can about it. I only know that Juan confessed that, having tasted of Mary Matilda's cake, he fell deeply in love with her and had come all this distance to ask her to be his, indissolubly.

"Still," said he, sadly, "'tis too much to ask you to link your destiny with one whose lineage is not known."

By this time they had reached the back-yard gate. Eddie Martin was sitting on the wood-pile talking with a weird old woman. The weird old woman scrutinized Mary Matilda closely.

"Do you know me?" she asked.

"No," said Mary Matilda.

"I have been serving ten years for a mild indiscretion," said the old woman, sadly. "I am the gypsy who told your fortune many years ago."

Then the old gypsy's keen eyes fell on Juan, the stranger. She gave a fierce cry.

"I have seen that face before!" she cried, trembling with emotion. "When I knew it, it was a baby face; but the spectacles are still the same!"

Juan also quivered with emotion.

"Have you a thistle mark on your left arm?" demanded the old gypsy, fiercely.

"Yes," he answered, hoarsely; and pulling up the sleeve of his linen ulster he exposed the beautiful emblem on his emaciated arm.

"It is as I suspected!" cried the old gypsy. "You are the Prince of Lochdougal, heir presumptive to the estates and titles of the Stuarts." And with these words the old gypsy swooned in Eddie Martin's arms.

When she came to, she explained that she had been a stewardess in the Lochdougal castle at Inverness when Juan's parents had been exiled for alleged conspiracy against the queen. Juan was then a prattling babe; but even then he gave promise of a princely future. Since his arrival at maturity his parents had feared to impart to him the secret of his lineage, lest he might return to Scotland and attempt to recover his estates, thereby incurring the resentment of the existing dynasty.

Of course when she heard of his noble lineage, Mary Matilda could do naught but accept the addresses of the brave prince. He speedily regained his health and flesh under the grateful influences of her cuisine. The wedding day has been set, and little Bessie is to be one of her bridesmaids. The brother Slosson is to be present, and he is to bring with him his other friend, whose name he will not mention, since his lineage is still in doubt.

CHAPTER III

SOME LETTERS

"There's no art," said the doomed Duncan, "to find the mind's construction in the face," nor after a somewhat extensive acquaintance with men and their letters am I inclined to think there is very much to be found of the true individuality of men in their letters. All men, and especially literary men, seem to consider themselves on dress parade in their correspondence, and pose accordingly. Ninety-nine persons out of a hundred are more self-conscious in writing than they are in talking. Even the least conscious seem to imagine that what they put down in black and white is to pass under some censorious eye. The professional writer, whether his reputation be international, like that of a Lowell or a Stevenson, or confined to the circle of his village associates, never appears to pen a line without some affectation. The literary artist does this with an ease and grace that provokes comment upon its charming naturalness, the journeyman only occasions some remark upon his effort to "show off." If language was given us to conceal thoughts, letter writing goes a step further and puts the black-and-white mask of deliberation on language.

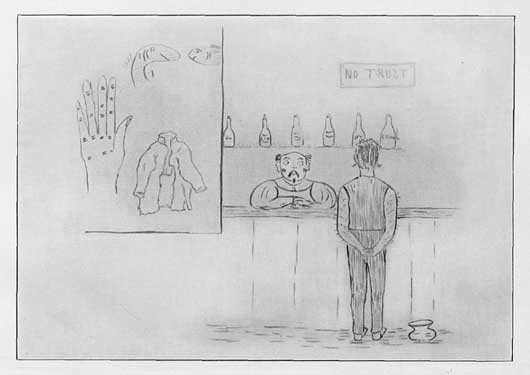

Eugene Field was no exception to the rule that literary men scarcely ever write letters for the mere perusal or information of the recipient. He almost always wrote for an ulterior effect or for an ulterior audience. But he seldom wrote letters deliberately for reproduction in his "Memoirs." If he had done so they would have been written so skilfully that he would have made himself out to be pretty much the particular kind of a character he pleased. For obvious reasons most of the communications that passed between Field and myself were verbal, across a partition in the office, or by notes that were destroyed as soon as they had served their purpose. That Field had other correspondents the following request for a postage stamp will testify:

THE GOOD KNIGHT'S DIPLOMACY.[1]

One evening in his normal plight

The good but impecunious knight

Addressing Thompson said:

"Methinks a great increasing fame

Shall add new glory to thy name,

And cluster round thy head.

"There is no knight but he will yield

Before thy valor in the Field

Or in exploits of arms;

And all admit the pleasing force

Of thy most eloquent discourse—

Such are thy social charms.

"Alike to lord and vassal dear

Thou dost incline a pitying ear

To fellow-men in pain;

And be he wounded, sick, or broke,

No brother knight doth e'er invoke

Thy knightly aid in vain.

"Such—such a gentle knight thou art,

And it is solace to my heart

To have so fair a friend.

No better, sweeter boon I pray

Than thy affection—by the way,

Hast thou a stamp to lend?"

"Aye, marry, 'tis my sweet delight

To succor such an honest knight!"

Sir Thompson straight replied.

Field caught the proffered treasure up,

Then tossing off a stirrup-cup

From out the castle hied.

July 2d, 1885.

Was ever request for so small a "boon" couched in such lordly pomp of phrase and in such insinuating rhyme?

It was shortly after Field secured this boon that he had his first opportunity to waste postage stamps on me. With a party of friends I went up to Mackinac Island to spend a few days. By the first mail that reached the island after I had registered at the old Island House, I received a letter bearing in no less than five different colored inks the following unique superscription:

For that Most Illustrious and Puissant Knight Errant,

Sir Slosson Thompson,

Erstwhile of Chicago, but now illumining

Mackinac Island,

Michigan,

Where, under civic guise, he is accomplishing prodigious

slaughter among the fish that do infest that coast.

It may be taken for granted that the clerks and the hotel guests were consumed with curiosity as to the contents of an envelope over which they had a chance to speculate before it reached me. These were:

CHICAGO, July 19th, 1885.

SWEET KNIGHT:

Heedful of the promise I made to thee prior to thy setting out for the far-distant province of Mackinac, I am minded to temporarily lay aside the accoutrements of war and the chase, and pen thee this missive wherein I do discourse of all that has happened since thy departure. Upon Saturday I did lunch with that ill-tempered knight, Sir P——, and in the evening did I discuss a goodly feast with Sir Cowan, than whom a more hospitable knight doth not exist—saving only and always thyself, which art the paragon of courtesy. This day did I lunch at my own expense, but in very sooth I had it charged, whereat did the damned Dutchman sorely lament. Would to God I were now assured at whose expense I shall lunch upon the morrow and the many days that must elapse ere thy coming hence.

By this courier I send thee divers rhymes which may divert thee. Soothly they are most honest chronicles, albeit in all modesty I may say they do not o'erpraise me.

The good Knight Melville crieth it from the battlements that he will go into a far country next week. Meanwhile the valorous Sir Ballantyne saweth wood but sayeth naught. That winsome handmaiden Birdie quitteth our service a week hence; marry, I shall miss the wench.

The fair lady Julia doth commend thy prudence in getting out of the way ere she reproaches thee for seducing the good Knight into that Milwaukee journey, of the responsibility of which naughtiness I have in very sooth washed my hands as clean as a sheep's liver.

By what good fortune, too, hast thou escaped the heat and toil of this irksome weather. By my halidom the valor trickleth down my knightly chin as I pen these few lines, and my shirt cleaveth to my back like a porous plaster. The good knight of the Talking Cat speaketh to me of taking his vacation in the middle of August, whereat I much grieve, having a mind to hie me away at that sweet season myself.

One sumptuous feast have we already had at thy expense at Boyle's, as by the check thou shalt descry on thy return. Sir Harper did send me a large fish from Lake Okeboji to-day, which the same did I and my heirdom devour triumphantly this very evening. I have not beheld the Knight of the Lawn since thy departure. Make fair obeisance to the sweet ladies who are with thee, and remember me in all courtesy to Sir Barbour, the good Knight of the Four Winds.

Kissing thy hand a thousand times, I sign myself Thy loyal and sweet servant,

FIELD,

The Good and Honest Knight.

Under another cover addressed ostentatiously:

"For the Good and Generous Knight,

Sir Slosson Thompson,

now summering amid rejoicings and with triumphant cheer at

Mackinac Island,

Michigan,"

came the following poem, entitled:

THE GOOD SIR SLOSSON'S EPISODE

WITH THE GARRULOUS SIR BARBOUR

Sir Slosson and companions three—

With hearts that reeked with careless glee—

Strode down the golden sand,

And pausing on the pebbly shore,

They heard the sullen, solemn roar

Of surf on every hand.

Then Lady Florence said "I ween"—

"Nay, 'tis not half so grand a scene,"

Sir Barbour quickly cried,

"As you may see in my fair state,

Where swings the well-greased golden gate

Above the foamy tide."

Sir Slosson quoth, "In very sooth"—

"Nay, say not so, impetuous youth,"

Sir Barbour made his boast:

"This northern breeze will not compare

With that delicious perfumed air

Which broods upon our coast."

Then Lady Helen fain would say

Her word, but in his restless way

Sir Barbour nipped that word;

The other three were dumb perforce—

Except Sir Barbour's glib discourse,

No human sound was heard.

And even that majestic roar

Of breakers on the northern shore

Sank to a murmur low;

The winds recoiled and cried, "I' sooth,

Until we heard this 'Frisco youth,

We reckoned we could blow!"

Sir Slosson paled with pent-up ire—

His eyes emitted fitful fire—

With rage his blood congealed;

Yet, exercising sweet restraint,

He swore no vow and breathed no plaint—

But pined for Good Old Field.

The ladies, too, we dare to say,

(If they survived that fateful day),

Eschew all 'Frisco men,

Who, as perchance you have inferred,

Won't let a person get a word

In edgewise now and then.

The subject of the good-natured and clever satire was our mutual friend, Barbour Lathrop, with whom I had been associated in journalism in San Francisco and who is famous from the Bohemian Club literally around the globe and in many of its most out-of-the-way islands as a most entertaining, albeit incessant, story-teller and conversationalist. Pretty nearly all subjects that interest humanity have engaged his attention. He could no more rest from travel than Ulysses; and he brought to those he associated with all the fruits that faring forth in strange lands could give to a mind singularly alert for education and experience under any and all conditions. His fondness for monologue frequently exposed him to raillery, like the above, in the column where Field daily held a monopoly of table talk.

But the episode with the "Garrulous Sir Barbour" was not the rhyme of chief interest (to Field and me) forwarded by "this courier."

This was confided to a third envelope even more elaborately addressed and embellished than either of the others, as follows:

For the valorous, joyous, Triumphant and Glorious Knight,

The ever gentle and Courteous Flower of Chivalry,

Cream of Knight Errantry and Pole Star of Manly virtues,

Sir Slosson Thompson,

who doth for the nonce sojourn at

Mackinac Island, Michigan,

Where under the guise of a lone Fisherman he is

regaled with sumptuous cheer and divers rejoicings,

wherein he doth right merrily disport.

The rhyme under this cover in which the impecunious knight did not "overpraise" himself bore the title "How the Good Knight protected Sir Slosson's Credit," and was well calculated to fill me with forebodings. It ran in this wise:

One midnight hour, Sir Ballantyne

Addressed Old Field: "Good comrade mine,

The times i' faith are drear;

Since you have not a son to spend

I would to God our generous friend

Sir Slosson now were here!"

Then spake the Impecunious Knight,

Regardful of his piteous plight:

"Odds bobs, you say the truth;

For since our friend has gone away,

It doth devolve on thee to pay—

Else would I starve i' sooth."

Emerging from their lofty lair

This much bereaved but worthy pair

Proceeded unto Boyle's,

Agreed that buttered toast would do.

Although they were accustomed to

The choicest roasts and broils.

"Heyday, sir knights," a varlet cried

('Twas Charlie, famous far and wide

As Boyle's devoted squire);

"Sir Slosson telegraphs me to

Deliver straightway unto you

Whatever you desire."

The knights with radiant features saw

The message dated Mackinaw—

Then ordered sumptuous cheer;

Two dollars' worth, at least, they "cheered"

While from his counter Charlie leered

An instigating leer.

I wot poor Charlie did not dream

The telegram was but a scheme

To mulct Sir Slosson's pelf;

For in the absence of his friend

The Honest Knight made bold to send

That telegram himself.

Oh, honest Field I to keep aright

The credit of an absent Knight—

And undefiled his name!

Upon such service for thy friends

Such knightly courtesies depends

Thy everlasting fame!

Two days later I received a postal written in a disguised hand by Ballantyne, I think, and purporting to come from "Charlie," showing the progress of the conspiracy to mulct Sir Slosson's pelf. It read:

FRIEND THOMPSON,

Fields and Ballantyne gave me the telegram tonight ordering one supper. But they have been eating all the week at your expense. Is it all right?

Yours,

CHAS. BURKEY.

And by the same mail came this comforting epistle from the arch conspirator:

CHICAGO, July the 22d, 1885.

DEAR SIR KNIGHT:

I have been too busy to reply to your many kind letters before this. On receipt of your telegram last night, we went to Boyle's and had sumptuous cheer at your expense. Charlie has begun to demur, and intends to write you a letter. Browne wrote me a note the other day. I enclose it to you. Please keep it for me. I hope your work will pan out more successfully.

I had a long talk with Stone to-night, and churned him up about the paper. He agreed with me in nearly all particulars. He is going to fire W—— when D—— goes (August 1). He said, "I am going to have a lively shaking up at that time." One important change I am not at liberty to specify, but you will approve it. By the way, Stone spoke very highly of you and your work. It would be safe for you to strike him on the salary question as soon as you please. The weather is oppressively warm. Things run along about so so in the office. Hawkins told me he woke up the other night, and could not go to sleep again till he had sung a song. The Dutch girls at Henrici's inquire tenderly for you.... Hastily yours,

EUGENE FIELD.

The note from Mr. Browne here mentioned related to the proposed publication of a collection of Field's verse and stories. The Browne was Francis F., for a long time editor of The Dial, and at that time holding the position of principal reader for A.C. McClurg & Co. As I remember, Mr. Browne was favorably disposed toward putting out a volume of Field's writings, but General McClurg was not enamoured of the breezy sort of personal persiflage with which Field's name was then chiefly associated. This was several years before Field made the Saints' and Sinners' Corner in McClurg's Chicago book-store famous throughout the bibliomaniac world by fictitious reports relating to it printed occasionally in his "Sharps and Flats" column. It was not until 1893 that McClurg & Co. published any of Field's writings.

My work to which Field refers was the collection of newspaper and periodical verse entitled "The Humbler Poets," which McClurg & Co. subsequently published.

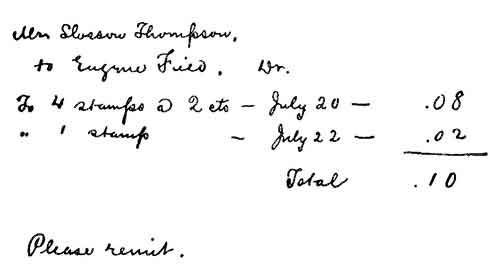

Enclosed in the letter of July 22d was the following characteristic account, conveying the impression that while he was willing to waste all the resources of his colored inks and literary ingenuity on our friendship, I must pay the freight. I think he had a superstition that it would cause a flaw in his title of "The Good Knight, sans peur et sans monnaie" if he were to add the price of a two-cent postage stamp to that waste.

A STAMP ACCOUNT.

| Mr. Slosson Thompson. | ||||||

| to Eugene Field, Dr. | ||||||

| To 4 stamps at | 2 cts | — | July 20 | — | .08 | |

| To 1 stamp | — | July 22 | — | .02 | ||

| Total | .10 | |||||

| Please remit. |

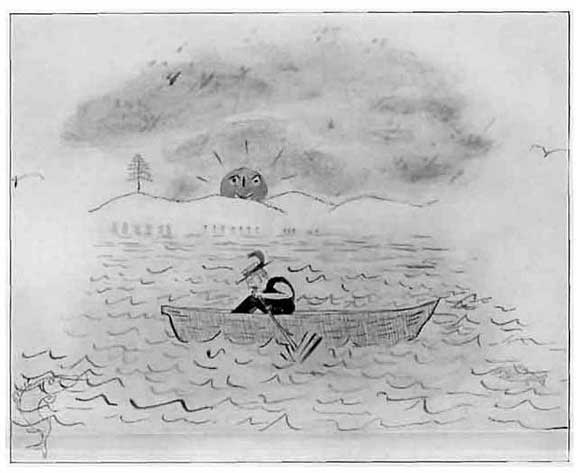

Shortly after my return from Mackinac, Field presented me with the following verses, enlivened with several drawings in colors, entitled "An Echo from Mackinac Island, August, 1885":

I.

A Thompson went rowing out into the strait—

Out into the strait in the early morn;

His step was light and his brow elate,

And his shirt was as new as the day just born.

His brow was cool and his breath was free,

And his hands were soft as a lady's hands,

And a song of the booming waves sang he

As he launched his bark from the golden sands.

The grayling chuckled a hoarse "ha-ha,"

And the Cisco tittered a rude "he-he"—

But the Thompson merrily sang "tra-la"

As his bark bounced over the Northern Sea.

II.

A Thompson came bobbling back into the bay—

Back into the bay as the Sun sank low,

And the people knew there was hell to pay,

For HE wasn't the first who had come back so.

His nose was skinned and his spine was sore,

And the blisters speckled his hands so white—

He had lost his hat and had dropped an oar,

And his bosom-shirt was a sad sea sight.

And the grayling chuckled again "ha-ha,"

And the Cisco tittered a harsh "ho-ho"—

But the Thompson anchored furninst a bar

And called for a schooner to drown his woe.

During the fall of 1885 I was again sent East on some political work that took me to Saratoga and New York. As usual, Field was unremitting in his epistolary attentions with which I will not weary the reader. But on the journey back from New York they afforded entertainment and almost excited the commiseration of a young lady travelling home under my escort. When we reached Chicago I casually remarked that if she was so moved by Field's financial straits I would take pleasure in conveying as much truage to the impecunious knight as would provide him with buttered toast, coffee, and pie at Henrici's. She accordingly entrusted me with a quarter of a dollar, which I was to deliver with every assurance of her esteem and sympathy. As I was pledged not to reveal the donor's name, this tribute of silver provided Field with another character, whom he named "The Fair Unknown," and to whom he indited several touching ballads, of which the first was:

THE GOOD KNIGHT AND THE FAIR UNKNOWN

Now, once when this good knight was broke

And all his chattels were in soak,

The brave Sir Thompson came

And saith: "I' faith accept this loan

Of silver from a fair unknown—

But do not ask her name!"

The Good Knight dropped his wassail cup

And took the proffered bauble up,

And cautiously he bit

Its surface, but it would not yield,

Which did convince the grand old Field

It was not counterfeit.

Then quoth the Good Knight, as he wept:

"Soothly this boon I must accept,

Else would I sore offend

The doer of this timely deed,

The nymph who would allay my need—

My fair but unknown friend.

"But take to her, O gallant knight,

This signet with my solemn plight

To seek her presence straight,

When varlets or a caitiff crew

Resolved some evil deed to do—

Besiege her castle gate.

"Then when her faithful squire shall bring

To him who sent this signet ring

Invoking aid of me—

Lo, by my faith, with this good sword

Will I disperse the base-born horde

And set the princess free!

"And yet, Sir Thompson, if I send

This signet to my unknown friend,

I jeopardize my life;

For this fair signet which you see,

Odds bobs, doth not belong to me,

But to my brawny wife!

"I should not risk so sweet a thing

As my salvation for a ring,

And all through jealous spite!

Haste to the fair unknown and say

You lost the ring upon the way—

Come, there's a courteous Knight!"

Eftsoons he spake, the Good Knight drew

His visor down, and waving to

Sir Thompson fond farewell,

He leapt upon his courser fleet

And crossed the drawbridge to the street

Which was ycleped La Salle.

Another bit of verse was inspired by this incident which is worth preserving: One night I was dining at the house of a friend on the North Side where the "Fair Unknown" was one of the company—a fact of which Field only became possessed when I left the office late in the afternoon. The dinner had not progressed quite to the withdrawal of the ladies when, with some confusion, one of the waiting-men brought in and gave to me a large packet from the office marked "Personal; deliver at once." Thinking it had something to do with work for the Morning News, I asked to be excused and hastily tore the enclosure open. One glance was enough to disclose its nature. It was a poem from Field, neatly arranged in the form of a pamphlet, with an illustration by Sclanders. The outside, which was in the form of a title page, ran thus:

HOW THE GOOD KNIGHT ATTENDED

UPON SIR SLOSSON:

BEING A WOEFUL TALE

OF

THE MOST JOYOUS AND DIVERTING DAYS

WHEREIN

KNIGHTS ERRANT DID COURTEOUSLY

DISPORT THEMSELVES

AND ACHIEVE PRODIGIES OF VALOR,

AND

MARVELS OF SWEET FRIENDSHIP.

And inside the plaintive story was told in variegated ink in the following lines:

One chilly raw November night

Beneath a dull electric light,

At half-past ten o'clock,

The Good Knight, wan and hungry, stood,

And in a half-expectant mood

Peered up and down the block.

The smell of viands floated by

The Good Knight from a basement nigh

And tantalized his soul.

Keenly his classic, knightly nose

Envied the fragrance that arose

From many a steaming bowl.

Pining for stews not brewed for him,

The Good Knight stood there gaunt and grim—

A paragon of woe;

And muttered in a chiding tone,

"Odds bobs! Sir Slosson must have known

'Twas going to rain or snow!"

But while the Good and Honest Knight

Flocked by himself in sorry plight,

Sir Slosson did regale

Himself within a castle grand—

of the Good Knight and

His wonted stoup of ale.

Mid joyous knights and ladies fair

He little recked the evening air

Blew bitterly without;

Heedless of pelting storms that came

To drench his friend's dyspeptic frame,

He joined the merry rout.

But underneath the corner light

Lingered the impecunious Knight—

Wet, hungry and alone—

Hoping that from Sir Slosson some

Encouragement mayhap would come,

Or from the Fair Unknown.

The drawing in this verse marks the beginning of the transfer of our patronage from the steaks and gamblers' frowns of Billy Boyle's to the oysters and the cricket's friendly chirps of the Boston Oyster House. The reference to Field's "dyspeptic frame" is not without its significance, for it was about this time that he became increasingly conscious of that weakness of the stomach that grew upon him and began to give him serious concern.

How Field seized upon my absence from the city for the briefest visit to bombard me with queer and fanciful letters, found another illustration during Christmas week, 1885, which I spent with a house party at Blair Lodge, the home of Walter Cranston Larned, whom I have already mentioned as the possessor of Field's two masterpieces in color. Each day of my stay was enlivened by a letter from Field. As they are admirable specimens of the wonderful pains he took with letters of this sort, and the expertness he attained in the command of the archaic form of English, I need no excuse for introducing them here. The first, which bears date "December 27th, 1385," was written on an imitation sheet of old letter paper, browned with dirt and ragged edged. In the order of receipt these letters were as follows:

Soothly, sweet Sir, by thy hegira am I brought into sore distress and grievous discomfiture; for not only doth that austere man, Sir Melville, make me to perform prodigies of literary prowess, but all the other knights do laugh me to scorn and entreat me shamelessly when I be an hungered and do importune them for pelf whereby I may compass victual. Aye, marry, by my faith, I swear't, it hath gone ill with me since you strode from my castle in the direction of the province wherein doth dwell Sir Walter, the Knight of the Tennis and Toboggan. I beseech thee to hie presently unto me, or at least to send silver or gold wherewith I may procure cheer—else will it go hard with me, mayhap I shall die, in which event I do hereby name and constitute thee executor of my estates and I do call upon the saints in heaven to witness the solemn instrument. Verily, good Sir, I do grievously miss thee and I do pine for thy joyous discourse and triumphant cheer, nor, by my blade, shall I be content until once more thou art come to keep me company.