Well-informed Visitor. That's Dr. KOCH, making his great discovery!

Unscientific V. What did he discover?

Well-inf. V. Why, the Consumption Bacillus. He's got it in that bottle he's holding up.

Unsc. V. And what's the good of it, now he has discovered it?

Well-inf. V. Good? Why, it's the thing that causes consumption, you know!

Unsc. V. Then it's a pity he didn't leave it alone!

First Old Lady (with Catalogue). It says here that "the note the page is handing may have come from Sir DIGHTON PROBYN, the Comptroller of the Royal Household" Fancy that!

Second Old Lady. He's brought it in in his fingers. Now that's a thing I never allow in my house. I always tell SARAH to bring all letters, and even circulars, in on a tray!

A. Sportsman. H'm—ARCHER, eh? Shouldn't have backed his mount in that race!

Gladstonian Enthusiast (to Friend, who, with the perverse ingenuity of patrons of Wax-works, has been endeavouring to identify the Rev. JOHN WESLEY among the Cabinet in Downing Street). Oh, never mind all that lot, BETSY; they're only the Gover'ment! Here's dear Mr. and Mrs. GLADSTONE in this next! See, he's lookin' for something in a drawer of his side-board—ain't that natural? And only look—a lot of people have been leaving Christmas cards on him (a pretty and touching tribute of affection, which is eminently characteristic of a warm-hearted Public). I wish I'd thought o' bringing one with me!

Her Friend. So do I. We might send one 'ere by post—but it'll have to be a New Year Card now!

A Strict Old Lady (before next group). Who are these two? "Mr. 'ENERY IRVING, and Miss ELLEN TERRY in Faust," eh? No—I don't care to stop to see them—that's play-actin', that is—and I don't 'old with it nohow! What are these two parties supposed to be doin' of over here? What—Cardinal NEWMAN and Cardinal MANNING at the High Altar at the Oratory, Brompton! Come along, and don't encourage Popery by looking at such figures. I did 'ear as they'd got Mrs. PEARCEY and the prambilator somewheres. I should like to see that, now.

An Aunt (who finds the excellent Catalogue a mine of useful information). Look, BOBBY, dear (reading). "Here we have CONSTANTINE'S Cat, as seen in the 'Nights of Straparola,' an Italian romancist, whose book was translated into French in the year 1585—"

Bobby (disappointed). Oh, then it isn't Puss in Boots!

A Genial Grandfather (pausing before "Crusoe and Friday"). Well, PERCY, my boy, you know who that is, at all events—eh?

Percy. I suppose it is STANLEY—but it's not very like.

The G.G. STANLEY!—Why, bless my soul, never heard of Robinson Crusoe and his man Friday?

Percy. Oh, I've heard of them, of course—they come in Pantomimes—but I like more grown-up sort of books myself, you know. Is this girl asleep She?

The G.G. No—at least—well, I expect it's "The Sleeping Beauty." You remember her, of course—all about the ball, and the glass slipper, and her father picking a rose when the hedge grew round the palace, eh?

Percy. Ah, you see, Grandfather, you had more time for general reading than we get. (He looks through a practicable cottage window.) Hallo, a Dog and a Cat. Not badly stuffed!

The G.G. Why that must be "Old Mother Hubbard." (Quoting from memory.) "Old Mother Hubbard sat in a cupboard, eating a Christmas pie—or a bone was it?"

Percy. Don't know. It's not in Selections from British Poetry, which we have to get up for "rep."

The Aunt (reading from Catalogue). "The absurd ambulations of this antique person, and the equally absurd antics of her dog, need no recapitulation." Here's "Jack the Giant Killer" next. Listen, BOBBY, to what it says about him here. (Reads.) "It is clearly the last transmutation of the old British legend told by GEOFFREY of Monmouth, of CORINEUS the Trojan, the companion of the Trojan BRUTUS, when he first settled in Britain. But more than this"—I hope you're listening, BOBBY?—"more than this, it is quite evident, even to the superficial student of Greek mythology, that many of the main incidents and ornaments are borrowed from the tales of HESIOD and HOMER." Think of that, now!

[BOBBY thinks of it, with depression.

The G.G. (before figure of Aladdin's Uncle selling new lamps for old). Here you are, you see! "Ali Baba," got 'em all here, you see. Never read your "Arabian Nights," either! Is that the way they bring up boys nowadays!

Percy. Well, the fact is, Grandfather, that unless a fellow reads that kind of thing when he's young, he doesn't get a chance afterwards.

The Aunt (still quoting). "In the famous work," BOBBY, "by which we know MASÛDI, he mentions the Persian Hezar Afsane-um-um-um,—nor have commentators failed to notice that the occasion of the book written for the Princess HOMAI resembles the story told in the Hebrew Bible about ESTHER, her mother or grandmother, by some Persian Jew two or three centuries B.C." Well, I never knew that before!... This is "Sindbad and the Old Man of the Sea"—let's see what they say about him. (Reads.) "Both the story of Sindbad and the old Basque legend of Tartaro are undoubtedly borrowed from the Odyssey of HOMER, whose Iliad and Odyssey were translated into Syriac in the reign of HARUN-UR-RASHID." Dear, dear, how interesting, now! and, BOBBY, what do you think someone says about "Jack and the Beanstalk"? He says—"this tale is an allegory of the Teutonic Al-fader, the red hen representing the all-producing sun: the moneybags, the fertilising rain; and the harp, the winds." Well, I'm sure it seems likely enough, doesn't it?

[BOBBY suppresses a yawn; PERCY's feelings are outraged by receiving a tin trumpet from the Lucky Tub; general move to the scene of the Hampstead Tragedy.

Spectators. Dear, dear, there's the dresser, you see, and the window, broken and all; it's wonderful how they can do it! And there's poor Mrs. 'OGG—it's real butter and a real loaf she's cutting, and the poor baby, too!... Here's the actual casts taken after they were murdered. Oh, and there's Mrs. PEARCEY wheeling the perambulator—it's the very perambulator! No, not the very one—they've got that at the other place, and the piece of toffee the baby sucked. Have they really! Oh, we must try and go there, too, before the children's holidays are over. And this is all? Well, well, everything very nice, I will say. But a pity they couldn't get the real perambulator!

"Oh, let us not like snarling tykes,

In wrangling be divided;

Till slap comes in an uncoo loon

And with a rung decide it.

Be Britain still to Britain true,

Among oursels united;

For never but by British hands

Maun British wrongs be righted!"

ROBERT BURNS's "Dumfries Volunteers."

Shade of BURNS, loquitur:—

O, rantin' roarin' JOHNNY BURNS,

My namesake—in a fashion,

You do my Scots the warst o' turns

Sae stirrin' up their passion.

Whence come ye, JOHNNY? Frae the Docks?

Or frae the County Council?

Sure Scots can do their ain hard knocks;

We take your brag and bounce ill!

Fal de ral, &c.

Does Cockneydom invasion threat?

Then let the louns beware, Sir!

Scotland, they'll find, is Scotland yet,

And for hersel' can fare, Sir.

The Thames shall run to join the Tweed,

Criffel adorn Thames valley,

'Ere wanton wrath and vulgar greed

On Scottish ground shall rally.

Fal de ral, &c.

A man's a man for a' that, JOHN,

And ane's as good as tither;

But that ship's crew is fated, JOHN,

That mutinies in bad weather.

Nae flouts to "honest industry"

Shall fa' frae the Exciseman;

[pg 27]But ane who blaws up strife like this,

Wisdom deems not a wise man.

Fal de ral, &c.

Scot business may be out o' tune,

True harmony may fail in't,

But deil a cockney tinkler loon

We need to rant and rail in't.

Our fathers on occasion fought,

And so can we, if needed;

But windy words with frenzy fraught

Sound Scots should pass unheeded.

Fal de ral, &c.

Let toilers not, like snarling tykes,

In wrangling be divided,

Till foreign Trade, which marks our Strikes,

Steps in, and we're derided.

Be Scotland still to Scotland true,

Amang oursels united;

'Tis not by firebrands, JOHN, like you

Our wrangs shall best be righted.

Fal de ral, &c.

The knave who'd crush the toilers doun,

And him, his true-born brither,

Who'd set the mob aboon the Crown,

Should be kicked out together.

Go, JOHN! Learn temperance, banish spleen!

Scots cherish throne and steeple,

But while we sing "God save the Queen,"

We won't forget the People.

Fal de ral, &c.

A LENGTHY NOVEL.—A Thousand Lines of Her Own, in 3000 vols., by the Authoress of A Line of Her Own, in 3 vols. N.B.—What a long line this must be to occupy three vols.! A work of and for a lifetime.

Small Stranger (to Master of the house). "OW MY! THE GENTLEMAN AS OPENS THE DOOR WILL GIVE IT YER, IF YER RING THAT BELL!"

During the preparation of Sir ARTHUR SULLIVAN's new Opera, Ivanhoe, a grave objection to the subject occurred to him, which was, that one of the chief personages in the dramatis personæ must be "Gilbert"—i.e., Sir Brian de Bois-Guilbert. True, that Sir Brian is the villain of the piece, but this, to Sir ARTHUR's generous disposition, only made matters worse. It was evident that he couldn't change the character's name to Sir Brian de Bois-Sullivan, and Mr. D'OYLEY CARTE refused to allow his name to appear in the bill except as Lessee. "I can't put him in simply as Sir Brian," said the puzzled Composer, "unless I make him an Irishman, and I don't think my librettist will consent to take this liberty with SCOTT's novel." "But the name in the Opera isn't pronounced the same as W.S.G.'s," objected D'OYLEY. "It will be outside the Opera by ninety out of a hundred," answered Sir ARTHUR. "But," continued D'OYLEY, persistently, "it isn't spelt the same." "No," replied Sir ARTHUR, "that's the worst of it; there's 'u' and 'i' in it; we're both mixed up with this Guilbert." Fortunately, the Composer and the Author made up their quarrel, and as a memento of the happy termination to the temporary misunderstanding, Sir ARTHUR, in a truly generous mood, designed to call the character "Sir Brian de Bois-Gilbert-and-Sullivan." Whether the mysterious librettist, whose name has only lately been breathed in the public ear, insisted on SCOTT's original name being retained or not, it is now pretty certain that there will be no departure from the great novelist's original nomenclature.

A BREACH OF VERACITY.—According to the papers, the Chief Secretary's Lodge in Dublin is blocked with parcels of clothing designed for the poor in the West of Ireland, sent in response to the request of Lord ZETLAND and Mr. ARTHUR BALFOUR. We understand there is no truth in the report, that amongst the first arrivals was a parcel containing Mr. O'BRIEN's br—s, with a note explaining, that as he was about to go to prison again, he had no further use for the article.

NEW IRISH DRINK.—The Parnellite "Split."

The excellent article in the Times on the 6th inst. upon CHARLES KEENE was worthy of its subject. The writer in the P.M.G. of a day earlier performed his self-imposed task with a judicious and loving hand, and, as far as I can judge, his account of our lamented colleague seems to be correct. As to our CARLO's Mastership in his Black-and-White Art, there can be but one opinion among Artists. Those who possess the whole of the Once a Week series will there find admirable specimens of CHARLES KEENE in a more serious vein. His most striking effects were made as if by sudden inspiration. I remember a story which exactly illustrates my meaning. An artistic friend was in KEENE's studio, while CARLO was at work, pipe in mouth, of course. "I can't understand," said his friend, "how you produce that effect of distance in so small a picture." "O—um—easy enough," replied KEENE. "Look here,"—and—he did it. But when and how he gave the touch which made the effect, his friend, following his work closely, was unable to discover. F.C.B.

PARS ABOUT PICTURES.—There is always something fresh coming out at Messrs. DOWDESWELL's Articultural Garden in Bond Street. Their latest novelty is the result of a caravan tour from Dieppe to Nice ("Dieppend upon it, he found it very nice!" said Young PAR, regardless of propriety and pronunciation) by Mr. C.P. SAINTON. CHARLES COLLINS utilised such an expedition from a literary point of view in his inimitable "Cruise upon Wheels," and this young artist has turned similar wanderings to good artistic account. His cartes de visite—no, I beg pardon, his caravans de visite—are numerous and varied. Verily, my brethren, all is caravanity! Not altogether, for Mr. SAINTON, in addition to returning with his caravan and himself, has brought back an interesting collection of original and delicate works in oil and silver-point—in short, taken every caravantage of his special opportunities. Yours parlously, OLD PAR.

"MAY IT PLEASE YOUR 'WARSHIPS.'"—Twenty-three American ships, 118 guns, and 3,000 men; six British ships, 52 guns, 1,229 men; and seven German ships, 42 guns, and 1,500 men—all in "Pacific" waters! Looks like Pacific, doesn't it?

[In a long communication which accompanied the MS. of this novel, the Author gives a description of his literary method. We have only room for a few extracts. "I have been accused of plagiarism. I reply that the accusation is ridiculous. Nature is the great plagiarist, the sucker of the brains of authors. There is no situation, however romantic or grotesque, which Nature does not sooner or later appropriate. Therefore the more natural an author is, the more liable is he to envious accusations of plagiarism.... Humour may often be detected in an absence of leg-coverings. A naval officer is an essentially humorous object.... As to literary style, it can be varied at pleasure, but the romantic Egyptian and the plain South African are perhaps best. In future my motto will be, 'Ars Langa Rider brevis,' and a very good motto too. I like writing in couples. Personally I could never have bothered myself to learn up all these quaint myths and literary fairy tales, but LANG likes it."]

My name is SMALLUN HALFBOY, a curious name for an old fellow like me, who have been battered and knocked about all over the world from Yorkshire to South Africa. I'm not much of a hand at writing, but, bless your heart, I know the Bab Ballads by heart, and I can tell you it's no end of a joke quoting them everywhere, especially when you quote out of an entirely different book. I am not a brave man, but nobody ever was a surer shot with an Express longbow, and no one ever killed more Africans, men and elephants, than I have in my time. But I do love blood. I love it in regular rivers all over the place, with gashes and slashes and lopped heads and arms and legs rolling about everywhere. Black blood is the best variety; I mean the blood of black men, because nobody really cares twopence about them, and you can massacre several thousands of them in half-a-dozen lines and offend no single soul. And, after all, I am not certain that black men have any souls, so that makes things safe all round, as someone says in the Bab Ballads.

I was staying with my old friend Sir HENRY HURTUS last winter at his ancestral home in Yorkshire. We had been shooting all day with indifferent results, and were returning home fagged and weary with our rifles over our shoulders. I ought to have mentioned that COODENT—of course, you remember Captain COODENT, R.N.—was of the party. Ever since he had found his legs so much admired by an appreciative public, he had worn a kilt without stockings, in order to show them. This, however, was not done from vanity, I think, but rather from a high sense of duty, for he felt that those who happened to be born with personal advantages ought not to be deterred by any sense of false modesty from gratifying the reading public by their display. Lord, how we had laughed to see him struggling through the clinging brambles in Sir HENRY's coverts with his eye-glass in his eye and his Express at the trail. At every step his unfortunate legs had been more and more torn, until there was literally not a scrap of sound skin upon them anywhere. Even the beaters, a stolid lot, had roared when old VELVETEENS the second keeper had brought up to poor COODENT a lump of flesh from his right leg, which he had found sticking on a thorn-bush in the centre of the high covert. Suddenly Sir HENRY stopped and shaded his eyes with his hand anxiously. We all imitated him, though for my part, not being a sportsman, I had no notion what was up. "What's the time of day, Sir HENRY?" I ventured to whisper. Sir HENRY never looked at me, but took out his massive gold Winchester repeater and consulted it in a low voice. "Four thirty," I heard him say, "they are about due." Suddenly there was a whirring noise in the distance. "Duck, duck!" shouted Sir HENRY, now thoroughly aroused. I immediately did so, ducked right down in fact, for I did not know what might be coming, and I am a very timid man. At that moment I heard a joint report from Sir HENRY and COODENT. It gave on the whole a very favourable view of the situation, and by its light I saw six fine mallard, four teal and three widgeon come hurtling down, as dead as so many door-nails, and much heavier on the top of my prostrate body.

When I recovered Sir HENRY was bending over me and pouring brandy down my throat. COODENT was sitting on the ground binding up his legs. "My dear old friend," said Sir HENRY, in his kindest tone, "this Yorkshire is too dangerous. My mind is made up. This very night we all start for Mariannakookaland. There at least our lives will be safe."

We were in Mariannakookaland. We had been there a month travelling on, ever on, over the parching wastes, under the scorching African sun which all but burnt us in our treks. Our Veldt slippers were worn out, and our pace was consequently reduced to the merest Kraal. At rare intervals during our adventurous march, we had seen Stars and heard of Echoes, but now not a single Kopje was left, and we were trudging along mournfully with our blistered tongas protruding from our mouths.

Suddenly Sir HENRY spoke—"SMALLUN, my old friend," he said, "do you see anything in the distance?"

I looked intently in the direction indicated, but could see nothing but the horizon. "Look again," said Sir HENRY. I swept the distance with my glance. It was a sandy, arid distance, and, naturally enough, a small cloud of dust appeared. Then a strange thing happened. The cloud grew and grew. It came rolling towards us with an unearthly noise. Then it seemed to be cleft in two, as by lightning, and from its centre came marching towards us a mighty army of Amazonian warriors, in battle-array, chanting the war-song of the Mariannakookas. I must confess that my first instinct was to fly, my second to run, my third, and best, to remain rooted to the spot. When the army came within ten yards of us, it stopped, as if by magic, and a stout Amazon, of forbidding aspect, who seemed to be the Commander-in-Chief, advanced to the front. On her head she wore an immense native jelibag, tricked out with feathers; her breast was encased in a huge silver tureene. Her waist was encircled with a broad girdle, in which were stuck all manner of deadly arms, stuhpans, sorspans, spîhts, and deeshecloutz. In her left hand she carried a deadly-looking kaster, while in her right she brandished a massive rolinpin, a frightful weapon, which produces internal wounds of the most awful kind. Her regiments were similarly armed, save that, in their case, the breast-covering was made of inferior metal, and they wore no feathers in their head-dress. The Commander held up her hand. Instantly the war-song ceased. Then the Commander addressed us, and her voice sounded like the song of them that address the butchaboys in the morning. And this was the torque she hurled at us,—

"Oh, wanderers from a far country, I am She-who-will-never-Obey, the Queen of the Mariannakookas. I rule above, and in nether regions, where there is Eternal Fire. Behold my Word goes forth, and the Ovens are made hot, and the Kee-chen-boi-lars are filled with Water. Over me no Mistress holds sway. All whom I meet I keep in subjection, save only the Weeklibuks; them I keep not down, for they delight me. And the land over which I reign is made glad with fat and much stored up Dripn. Who are ye, and what seek ye here? Speak ere it be too late!" And as she ceased the whole army broke forth into a chorus, "She-who-will-never-Obey has spoken! The Word is gone forth! Speak, speak!" I confess I was alarmed, and my fears were not diminished when two of the Skulrimehds (a sort of native camp-follower) came up to COODENT and me, and actually began to make love to us in the most forward manner. But Sir HENRY maintained his calm demeanour. "She-who-will-never-Obey," he said, "we are peaceful traders. We bring no Commission—" how his sentence would have ended will never be known. Certain it is that what he said roused the Amazons to a frenzy of passion. They yelled and danced round us. "He who [pg 29] brings no Commission must die!" they shouted; and in a moment we found ourselves bound tightly hand-and-foot, and marching as prisoners of war in the centre of the Mariannakookaland army.

It is unnecessary to go through the details of our marvellous escape from the lowest dungeon of the royal Palace of SURVAN TSAUL, where for months we were immured on a constant diet of suet pudding. Of course we did escape, but only after killing ten thousand Mariannakookas, and then swimming for a mile in their blood. COODENT brought with him a very pretty Skulrimehd who had grown attached to him, but she drooped and pined away after he lost his false teeth in crossing a river, and tried to replace them with orange-peel, a trick he had learnt at school. Sir HENRY's fight with She-who-will-never-Obey is still remembered. He will carry the marks of her nails on his cheeks to his grave. I myself am tired of wandering. "Home, Sweet Home," as the Bab Ballads have it, is the place for me.

I went to see the Pantomime this Christmas in our town.

We laughed enough the opening night to bring the theatre down.

The piece was Burleybumbo, the Old Giant, and his Men;

Fairy Starlight, Little Popsey, and the Demon of the Glen.

The Supers were collected from the local talent round,

And for Burleybumbo's servant the Blacksmith, JOHN, they found;

A stalwart varlet was required to carry off his foes

To Burleybumbo Castle, where he ate them as he chose.

His minions, who wore hideous masks, had nothing much to say,

So an IRVING was not wanted to do their part of the play.

On this eventful night the house was packed from roof to pit,

And the Manager was jubilant at having made a hit.

The Curtain drawing slowly up, revealed a flowery glade,

In which the Fairy Starlight and her lovely maidens played.

The wicked Demon then came on, and round the stage did glower;

No mortal man could e'er withstand his wrath or evil power.

Last of all came Burleybumbo with his crew, a motley horde,

Our old friend, Blacksmith JOHN, was in attendance on his lord.

They were singing and carousing, when a man rushed in to say

That a dozen wealthy travellers were coming down that way.

The band dispersed, and hid themselves, in hopes that they might plunder

The unsuspecting wayfarers. Alas! now came the blunder:

Old JOHN he wouldn't hide himself, but coolly walked about

Advancing to the footlights, he looked around—but hark! a shout:—

"Confound you! Dash my—! Just come off! Hi, you! Who are you? JOHN!"

"Not if I knowsh it, jolly old pal! I've only just come on!"

Thus saying, he lumbered round the stage. The Prompter's heart had sunk:

No doubt about the matter—Burleybumbo's man is drunk!

"Come off! Come off!" from every wing was now the angry cry.

"Me off, indeed! Oh, would yer? Sh'like to see the feller try!"

Burleybumbo then appeared, and vainly tried to drag him back.

JOHN stove his pasteboard head in with a most refreshing crack.

The wicked Demon now rushed on; his supernatural might

Was very little use to him on this surprising night.

He tried to push him down the glade, but here again JOHN sold him;

He caught the Demon round the waist, and at the Prompter bowled him.

Ah! such a shindy ne'er was seen, such riot and such rage—

It was the finest "rally" ever seen on any stage!

'Mid shrieks and cat-calls, whistles shrill, hysterics and guffaws,

They rang the Curtain down amidst uproarious applause.

The piece is still a great success; but, I regret to say,

JOHN's name appears no longer in the bills of that fine play!

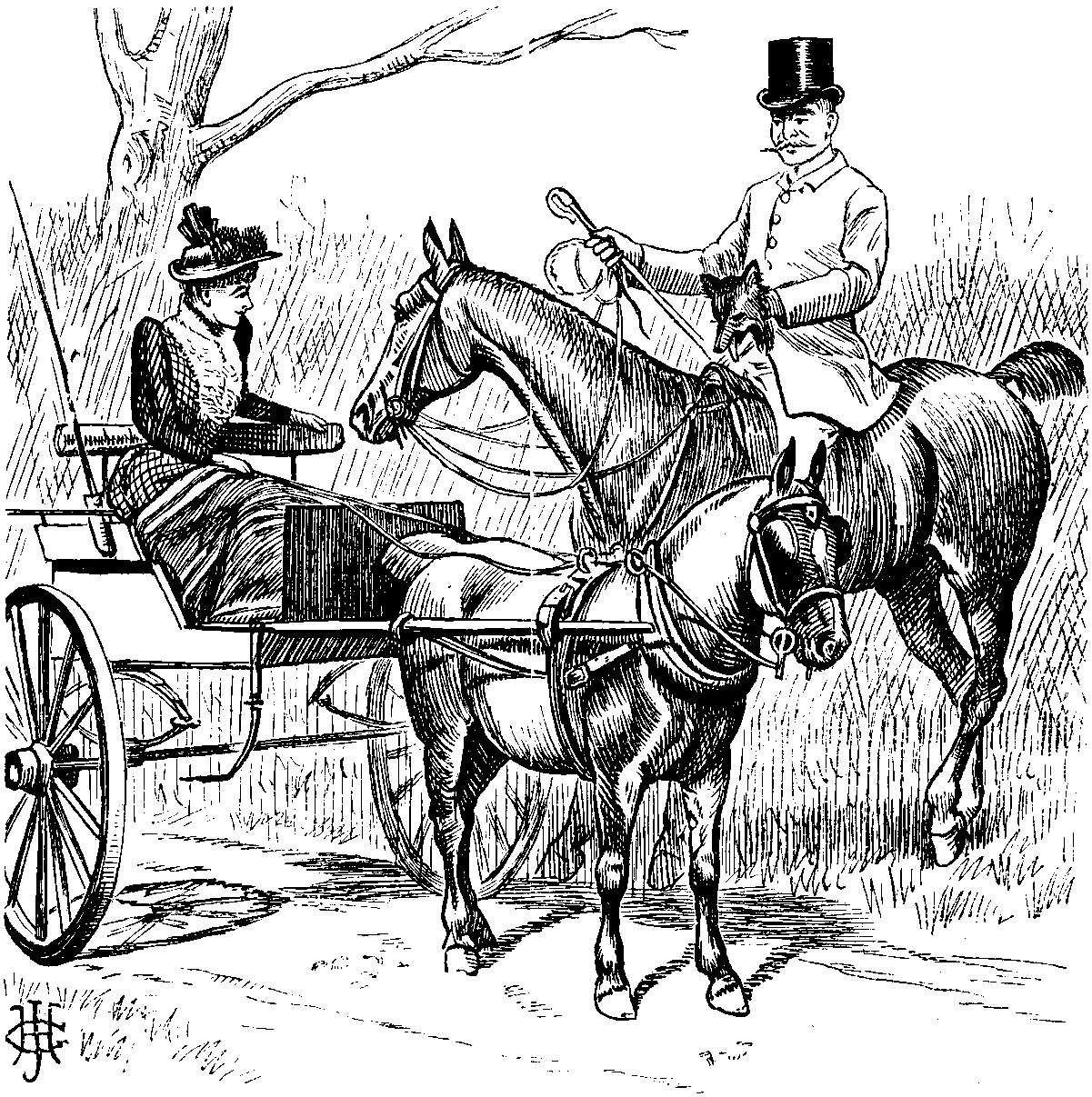

Fair Maiden, you're looking a vision of beauty,

You may comfort yourself you've no rival to fear;

But you won't take it ill if I feel it my duty

To whisper a word of advice in your ear.

Now, the word would be this—when the daylight is dawning,

Or, at any rate, when it's more early than late,

Pray remember the coachman, who, fitfully yawning

Outside in the street, finds it weary to wait.

You reck not at all of the hours that are fleeting,

You ask for an "extra"—you can't be denied.

But though, doubtless, soft nothings may set your heart beating,

Yet they're awfully cold for the people outside.

Want of thought, not of heart, is the reason as ever,

So if you find leisure to read through this rhyme,

When you order your carriage, in future endeavour

To prevent any waiting—by being in time,

The Publisher of The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, earnestly requests the reviewer, appealing to his heart in the reddest of red ink, on a slip of paper pasted on to the cover of the Magazine, not to extract and quote more than one column of "Talleyrand's Memoirs," which appear in this number for January. The Publisher of the C.I.M.M. does not appeal personally to the Baron—who is now the last, bar one, of the Barons, and that bar one is one at the Bar,—but, for all that, the Baron hereby and hereon takes his solummest Half-a-Davey or his entire Davey, that he will not write, engrave, or represent, or cause to be, &c, for purposes of quotation, one single word, much less line, of Tallyho—beg pardon, of Talleyrand,—extracts from whose memoirs are now appearing in the aforesaid C.I.M.M. But all he will say at present is this, that, if the secret and private Memoirs haven't got in them anything more thrilling or startling, or out of the merest common-place, than appears in this number of the C.I.M.M., then the Baron will say that he would prefer reading such contributions as M. de BLOWITZ's story of "How he became a Special," or The Pigmies of the African Forest by HENRY M. STANLEY in the same number of this Mag.

What the Baron dearly loves is, ELLIOT STOCK-IN-TRADE The Book-worm, always most interesting to Book-worms, and almost as interesting to Book-grubs or Book-butterflies. By the way, the publishing office of The Book-worm ought to be in Grub Street. For what sort of fish is The Book-worm an attractive bait? I suppose there are queer fish in the Old Book trade that can take in any number of Book-worms, as is shown from a modern instance, well and wisely commented upon in this very number for January, No. 38, which is excellent food for worms; the whole series, indeed, must be a very Diet of Worms. Success to the Book-worm! May it grow to double the size, and be a glow-worm, to enlighten us in the bye-paths of literature. "Prosit!" says the Baron.

I would that some one would write of BROWNING's work as HENRY VAN DYKE has written of TENNYSON's. To the superficial and cursory reader of the Laureate, the Baron, sitting by the fire on a winter's night, the wind howling over the sea, and the snow drifting against the window, and being chucked in handfuls down the chimney, and frizzling on the fire, says, get this book, published by ELKIN MATHEWS: ça donne à penser, and this is its great merit. "Come into the Garden, Maud"—no, thank you, not to-night; but give me my shepherd's pipe, with the fragrant bird's-eye in it, with [Greek: ton grogon], while I sit by the cheerful fire, in the best of good company—my books.

Our Mr. GRIFFITHES (CHESTER, MAYHEW, BROOME, AND GRIFFITHES) has been all the way From Bedford Row to Swazieland, and has written a lively narrative of his perilous journey. He went on a professional retainer. You don't catch Bedford Row in Swazieland on other terms. Being there, he kept his eyes open, saw a good deal, and describes his impressions in racy fashion. He did not like the coffee served en route, and was disappointed with the Southern Cross; but on the whole enjoyed the trip. One would naturally expect that the price of his book would be six-and-eight-pence, or, regarding it in the form of a letter, three-and-fourpence, but BRADBURY, AGNEW, & Co. issue it at a shilling.

THE BARON DE BOOK-WORMS & Co.

Our Artist. "WELL, HOW DO YOU LIKE THE PORTRAITS, MISS BUNNY? THE SITTERS ARE ALL OLD FRIENDS OF YOURS, I BELIEVE?"

Miss Bunny (triumphantly). "YES; AND, ONLY THINK, I'VE ACTUALLY MANAGED TO GUESS THEM ALL!"

Seal, suddenly emerging, loquitur:—

Belay, you two lubbers, avast there! avast there!

What signifies squalling and squabbling?

You're both argufying a good bit too fast there,

Whilst that which you stand on seems wobbling.

You'll be in a mess, Messmates, shortly, the pair of you.

Give me a thought in the matter!

My interest's at stake, and it isn't quite fair of you

Me to ignore 'midst your clatter.

If 'twere not for me, Mates, this cold Behring's Sea, Mates,

Would hardly strike you as so tempting.

Do grant your poor prey, if I may make so free, Mates,

From slaughter some annual exempting!

I'm worried and walloped without intermission

Until even family duties

Quite fail, whilst your countrymen cudgel and fish on.

By Jingo, some of 'em are beauties!

My poor wife and children have not half a chance, Mates.

That's not to your interest, I reckon.

Cease shindy, and on a new course make advance, Mates,

Where sense and humanity beckon.

There's not much of either in cruelly clubbing

My progeny all out of season;

And if you are bent upon mutual drubbing,

You must quite have parted with reason.

Mare clausum, be blowed! That's all BLAINE's big bow-wow, Mates.

Men can't thus monopolise oceans.

Diplomacy must find a compromise now, Mates,

And, well—I have told you my notions.

Give me a close-time,—I shall be very grateful—

And leave the Sea open! What more, Mates?

For brothers like you to be huffing, is hateful.

Be friends, think of me, and—bong swor, Mates!

[Dives under.

| Morning Fast. |

Mineral and Parl. |

General Express. |

Traffic and Even. Mail. |

|

| Edinburgh (Waverley Station) |

7 A.M. to 9.30 |

11 A.M. A | Noon F | 9 P.M. L |

| Carlisle | 12.15 | ... | ... | ... |

| Hawick | 4.30 | B | ... | ... |

| Galashiels | 9.45 | ... | 2.15 G | 1 A.M. M |

| Motherwell{ | 1 P.M. (Stopped by riot) |

}4 P.M. C | 3.19 H | 3.20 N |

| St. Margaret's Works | 3.30 | 5 D | ... | ... |

| Perth | 9.45 A.M. | ... | 11.26 I | ... |

| Glasgow | 12.30 P.M. | ... | ... | ... |

| Aberfeldy | 6.13 | ... | ... | ... |

| Dundee | 1.12 A.M. | 3 A.M.to 9 | ... | ... |

| Inverness | 9.23 | ... | 3.5 J | ... |

| Aberdeen | 11.6 | 7 P.M.? E | 1 A.M. K | O |

A—Takes delayed pig-iron and third-class passengers. B—Half of train stops here through breaking an axle-pin. C—Passengers, for protection, get under seats of carriages. D—Stops for repairs. E—Having had a collision at the junction for Aberfeldy, will come on, if there are any passengers equal to finishing the journey.

F—Starts under the management of a Director, and, owing to a misunderstanding, dashes off to Aberdeen, without stopping. G—Doesn't stop, but knocks over a station-master. H—Is pelted as it tears through the station by ex-employés. I—Knocks over another station-master. J—Meets a pilot-engine, which it splits in half. K—Goes at full speed through the end of the terminus, depositing the passengers in a heap in the middle of the town.

L—Train starts, made up of horse-boxes and luggage-vans full of three weeks' arrears of parcels, first-class carriages, Post-office van, fifty coal-trucks, and a wild beast show, the Directors wishing to make up for lost time. M—Train breaking down here, mail and passengers only forwarded. N—Train attacked by rioters. Pitched battle with the passengers. O—Telegram from Motherwell saying, that owing to police intervention, train starts the day after to-morrow.

THE SEAL. "BELAY, YOU TWO JOHNNIES!—AVAST QUARRELLING! GIVE ME A 'CLOSE-TIME,' AND LEAVE THE 'SEA' AN OPEN QUESTION."

Fair New-Englander (spending the Winter in the Old Country). "OH, WHAT A LOVE! AND IS IT THE FIRST YOU HAVE SHOT THIS YEAR, CAPTAIN RASPER?"

ACT I.—"PAST."—Interior of the Savings Bank Department of the G.P.O. Employés engaged upon their work. The hour for customary cessation of labour strikes.

Official of a Higher Grade. Officers and Gentlemen, the exigencies of the Public Service require your presence for some time longer. I beg you to continue your work.

A Hundred Employés. Never! (Aside.) Ha! ha! the employment of Female Clerks is avenged!

Off. (almost in tears). Reconsider your decision, I beg—I implore!

Another Hundred Employés. Never! (Aside.) Seven hours a day and no longer—shall be secured at one fell swoop!

Off. (with indescribable emotion). Oh, my country! Oh, my Savings Bank Depositors! Oh, my dignity of the Civil Service!

[Faints in the arms of faithful Employés, whilst the other Clerks defiantly depart. Tableau.

ACT II.—"PRESENT."—Magnificent apartments of the P.-M.-Gen. in the G.P.O. Deputation of contrite Employés listening to the eloquent speech of their Official Chief.

P.M.G. (in effect). I am delighted that you are such good fellows. Your conduct in owning that you were wrong in refusing to work after regular official hours, almost effaces a painful page in the history of St. Martin's-le-Grand. Let it be clearly understood that extra work is not compulsory, but, if not undertaken, may lead (as in the present instance) to immediate suspension, if not dismissal. Surely no one can object to that? (Contrite Officials express mournful approval.) And now good-bye, and A Happy New Year. As for the future—hope, my good friends, hope!

[Exeunt the contrite Employés, leaving the Officials of a Higher Grade agitating the nerves controlling their eyelids spasmodically.

ACT III.—"FUTURE."—Same Scene as Act I. Venerable Employés discovered, after twenty years' further service.

First Venerable Employé. Remember the words spoken a score of winters ago—Hope, brother, hope!

Second Venerable Employé. Yes—Hope, brother, hope!

[As the Scene closes, the entire Establishment are left continuing the self-sustaining, but rather profitless employment, indefinitely. Curtain.

A Son of the Pool. By the Author of A Daughter of the Pyramids.

What words avail to honour friends departed,

Gone from the gatherings which so long they graced?

What phrase seems fit when comrades loyal-hearted

Mourn a loved presence late by death displaced?

No formal elegiacs fashioned coldly,

Beseem the memory of that manly soul,

Whose simple, downright spirit trod so boldly

Life's most sequestered ways from start to goal.

Not rank's trim pleasaunce, nor parades of fashion

Tempted his genius; his the great highway

Where, free from courtly pride and modish passion,

Toil tramps, free humours crowd, rough wastrels stray.

Therein his magic pencil laboured gladly,

Fixing for ever on his chosen page

In forms fond memory now reviews so sadly

The crowded pageant of a passing age.

What an array! How varied a procession!

The humours of the parlour, shop, and street;

Philistia's every calling, craft, profession,

Cockneydom's cheery cheek and patter fleet.

Scotch dryness, Irish unction and cajolery,

Waiterdom's wiles, Deacondom's pomp of port;

Rustic simplicity, domestic drollery,

The freaks of Service and the fun of Sport;

And all with such true art, so fine, unfailing,

Of touch so certain, and of charm so fresh,

As to lend dignity to Cabmen railing,

To fustianed clods and fogies full of flesh.

Nor human humours only; who so tender

Of touch when sunny Nature out-of-doors

Wooed his deft pencil? Who like him could render

Meadow or hedgerow, turnip-field, or moor?

Snowy perspective, long suburban winding

Of bowery road-way, villa-edged and trim.

Iron-railed city street, where gas-lamps blinding

Glare through the foggy distance dense and dim?

All with that broad free force, whose fascination

All felt, and artists most, that dexterous sleight

Which gave our land the unchallenged consummation

Of graphic mastery in Black-and-White.

Pleasant to dwell on, and a proud possession,

Now the tired hand that shaped that world is still,

Leaving an ineffaceable impression

Upon the age that fired its force and skill.

Honoured abroad as loved at home, how ample,

The tribute to that modest spirit paid!

To pushing quackery a high example,

A calm rebuke to egotist parade!

Frank, loyal, unobtrusive, simple-hearted,

Loving his book, his pipe, his song, his friend,

Peaceful he lived and peacefully departed,

A gentle life-course, with a gracious end.

Irreparable loss to Art, deep sorrow

To those his comrades, who so loved the man,

And who had hoped for many a sunny morrow

To greet that gallant spirit in the van.

That tall, spare form, that curl-crowned head, the knitting

Of supple hands behind it as he sat,

That quaint face-wrinkling smile like sunshine flitting,

The droll, dry comment, the quotation pat;

The small oft-loaded pipe, of ancient moulding,

The brazen box that held the well-loved weed;

Who shall forget who once was graced by holding

In friendship's clasp the hand now still indeed?

Farewell, great artist, comrade staunch and loyal!

Few simpler lives our feverish age hath seen.

Could pomp high-pinnacled, or trappings royal,

Add honour to the memory of CHARLES KEENE?

Over a series of weeks preceding Christmas, Europe was disturbed by rumours of a momentous interview reported to have taken place on the banks of the unsuspecting Bosphorus. One of the parties to the conference was his Imperial Majesty the SULTAN. The other was an English Statesman, the trusted counsellor of an Ex-Premier, and believed in family circles to be the real author of some of his supreme measures. The naturally retiring disposition of the Statesman in question, and his inviolable reticence in respect of any matter concerning himself, made it difficult to arrive at the truth. Doubtless the stupendous event—the possible consequences of which on European affairs Time will work out—would have remained for ever hidden but for the ruthless action of "the London Correspondents of various provincial papers, who gave in their London letters more or less inaccurate reports of the event." How they came to know anything about it admits of only one conclusion. The SULTAN must have told them. The event was too important to be left to this haphazard kind of record, and, accordingly, the Speaker has been favoured with a narrative of what took place, the signature disclosing the fact that the other party to the interview was the SHAH LEFEVRE.

The SHAH's account, regarded as a record of a historical event, is manifestly hampered by that modest and insatiable desire for self-effacement which marks this eminent man. We see anonymous "persons who had access to the SULTAN approaching" the SHAH, and "suggesting to him that he ought to apply for an audience." We see him "declining to do so on the ground that, having taken an active part in the agitation in England on the subject of the Bulgarian atrocities in 1877, it would not be right that I should thrust myself on the attention of the SULTAN." It is generally thought at Stamboul and elsewhere that Mr. GLADSTONE was chiefly responsible for the memorable agitation referred to. But the SHAH is not the man to hide the truth. Also, "I wished to be free to say what I thought about the condition of Turkey on my return to England." That was only fair to waiting England. No use the SULTAN trying to "nobble" this relentless man. So it came to pass that he went to the Palace, reluctant, but "feeling we could not refuse such a command from the Sovereign of the country." He talked with CHAKIR PACHA and WAHAN EFFENDI; saw the SULTAN's horse; hung about for hours; no SULTAN appeared; went back to hotel quivering under the insult. Had framed telegram ordering the British Fleet to the Bosphorus, when VAMBÉRY turned up, pale and trembling; besought the SHAH to do nothing rash; explained it was all a mistake. This followed up by invitation to dine at the Palace the following day.

All this, and what followed at the dinner; how there were "excellent wines, electric lights, and a great display of plate"; how the SULTAN, concentrating his attention on the SHAH, and forgetful of poor FREDERICK HARRISON, who had, somehow, been elbowed into obscurity, paid court to this powerful personality; how he received him on the daïs, and now cunningly, though ineffectually, he endeavoured to secure on the spot the evacuation of Egypt, is told in the SHAH'S delicious narrative.

Mr. Punch, sharing in the thrilling interest this disclosure has created throughout the civilised world, has been anxious to complete the record by supplementing the SHAH's account of the interview, with the SULTAN's own version. This was, at the outset, difficult. Obstacles were thrown in the way, but they were overcome by the pertinacity and ingenuity of Our Representative, who at last found himself seated with the SULTAN on the very daïs from which SHAH LEFEVRE had conferred with his Imperial Majesty whilst other of the forty guests, "including the Austrian Ambassador," looked on, green with envy.

"It's a curious thing," said the SULTAN, laying down a book he had been reading when Our Representative entered, "that, when you were announced, I had just come upon a reference by your great Poet to your still greater Statesman. You know the line in Lockandkey Hall,—

"'Oh the dreary, drear LEFEVRE! Oh the barren, barren SHAW!'"

"That," Our Representative writes, "is not precisely the line as I remember it; but I make it a rule never to correct a SULTAN."

Accordingly His Majesty proceeded: "And so, my good Cousin, Mr. Punch, wants to know all about this interview, the bruit of which has shaken the Universe. His wishes are commands to me. In the first place, I will tell you (though this is not for publication), that it was by the merest accident I had the advantage of knowing your great countryman. I heard there had come to Constantinople one FREDERICK HARRISON, head of a sect called the Positivists. I am, you know, in my way, and within the limits of my kingdom, one of the most absolute Positivists of the age. I wanted to see the English apostle, and told them to ask him to dinner. Somehow things got mixed up, and, at the preliminary morning call, the SHAH LEFEVRE walked in. Had never heard of him before, but gathered from CHAKIR PACHA, who had been talking to WAHAN EFFENDI, who, had seen WOODS PACHA, who had spent an hour with VAMBÉRY, upon whom SHAH LEFEVRE had called, that the SHAH was really the mainspring of the Liberal Party in England, GLADSTONE being merely figure-head, HARCOURT in his pay, and CHAMBERLAIN suffering in exile under his displeasure. Allah is Good! Here was a chance thrown into my hands. I forgot all about FREDERICK HARRISON; told CHAKIR PACHA and WAHAN EFFENDI to entertain the SHAH in the ante-chamber with coffee and cigarettes, drawing him out on Armenia and Egypt. Meanwhile I crept under the sofa, and heard every word. The SHAH very stern about Armenia, could not be drawn about Egypt. At end of hour and half began to get tired under sofa; managed to stick in WAHAN EFFENDI's Wellington boot a note, on which I had written, 'Take him to see my horse.' So they went off to stable, and, as soon as coast was clear, I crept out; shut myself up in room for rest of day. Heard afterwards that they came back, the SHAH much impressed with appearance of my horse; resumed conversation on Armenia and Egypt for another hour; at last got rid of SHAH.

"At night VAMBÉRY, disguised as melon-seller, entered Palace and gained access to my room. Told me fearful mess had been made of matters. The SHAH really didn't care about seeing the horse; wanted to see me. Talks about ordering round the Fleet. 'Better ask him to dinner,' said VAMBÉRY; so despatched Grand Chamberlain in carriage and six. The SHAH mollified; gave him a good dinner: plenty of electric lights. Afterwards he was good enough to see me on the daïs. Tried to get him to promise alteration in attitude of English Liberal Party towards me; also wanted him to settle at once withdrawal of troops from Egypt, But, though most urbane in manner, exceedingly cautious. Not to be drawn. Talk about Eastern statecraft! nothing to you English, as represented by jour SHAH LEFEVRES. When I pressed him to come to point about Egypt, he said, 'On this subject I can only speak my own views. I am not authorised to speak on behalf of those I am politically associated with, but personally I am opposed to the occupation of Egypt by English troops.' There's an answer for you! Your MACHIAVELLIS, your TALLEYRANDS not in it. Felt I had wasted some time, and given away a dinner all for nothing, except the memory that will ever rest with me of having been privileged to see this remarkable man standing on my daïs."

Here the SULTAN clapped his hands three times, and Our Representative, being carefully placed in a sack, was dropped into the Bosphorus, whence he was rescued in time to send off this despatch for publication in the current Number.

ACCIDENT ON THE ICE.—The other day a gentleman, well known in the world of Sport and Art, was skating on the Serpentine, and fell in with a friend. Both were getting on well when our reporter left.

"And I do not hesitate to betray to you this secret, that not infrequently in the summer months, when winding my way homewards after midnight, sometimes very long after it, from the House of Commons, I have stopped my course for a moment by the side of the drinking fountain in Great George Street, Westminster, when there was nobody to look at me, and have indulged in the refreshing draught which was there afforded me, feeling at the same time that I was not performing any action which could expose me to the resentment or displeasure of my excellent friend whose name is well known to you all—Sir WILFRID LAWSON."

I'd be a criminal, born in a slum,

Where refuse, and rowdies, and raggedness meet;

For when to the court for my trial I come,

I'll be gazed on by all that is gracious and sweet.

Fair dames of the land will acknowledge my power,

And Scientists sage will be slaves at my feet;

Offers of marriage I'll get in full shower,

And fools in my cause in their thousands will meet.

They'll trot out each new "scientific" vagary,

Some hope of escape to my prison to bring,

And scribes on my case will be sportive and airy

And tell how I look, eat, sleep, dress, talk or sing.

Those I have butchered will get scant attention,

Interest's sure to be centred in me.

Painters will picture me, poets may mention,

Beauties discuss me at five o'clock tea.

Mad doctors will fight o'er my mental condition,

Hypnotists swear I was somebody's tool;

And if I'm condemned, why a Monster Petition

Will promptly be signed by each faddist and fool.

Murder—and good Dr. LIÈGOIS of Nancy

Will back you, LABRUYÈRE will help you away.

I'd be a Murderer, that is my fancy,

He is the only true Hero to-day!

The Strike in Scotland.—You might suggest, that were it in Ireland, one might see a rail way out of it, or rather in it. This jest may be expected to be appreciated by a parson's wife of the sharper sort. Something ought to be got out of the visit of the agitator BURNS to the North. Example of what can be done in this direction:—"People who play with fire (persons who go in for strikes) must expect BURNS." However, be careful not to say this to a Scotchman, or he may want your blood before you get to the cigarettes. North Britons are very jealous of the reputation of their national poet, and permit no jokes upon the subject. You see, in letting off your witticism at a Scotchman, you would have to explain that it was a joke. You might also hint that it was "hard lines" for the Railway Companies concerned; but this will provoke gloom rather than gaiety amongst those who have invested in Caledonians and North British. If you talk about the riots in connection with the movement, you might say that the pugnacious rioters remind you of safety matches, "for they not only strike, but strike on the box!"

The Parnell Negociations in France.—You can say something about O'BRIEN's invitation to Mr. PARNELL to pay him an evening visit on the French coast, reminds you of the once popular song, "Meet me by Moonlight, Boulogne." If you are told that "Boulogne" should be "Alone," return, "Precisely—borrowed a word—Boulogne was a loan." This ought to go with roars. At a Smoking Concert you might suggest that Mr. O'BRIEN was just the man to settle a quarrel, because even when he was in prison he took an absorbing interest in the proper adjustment of breeches!

The Row at the Post Office.—As the Savings' Bank Department has for years been the Cinderella of the Civil Service, this is a subject that will not create much interest; however, you might possibly extract a pleasantry out of the name of the present Postmaster-General in connection with the now-appeased employés. With a little trouble you should be able to say something quite sparkling about what the "officers" hoe to Raikes!

The Portuguese Difficulty in Africa.—Rather a good subject at a Christmas Dinner, where relatives (on particularly affectionate and intimate terms) are gathered together. Say you have got to the dessert, and you start the subject. Observe that it is fortunate that the SULTAN OF TURKEY is not interested in the matter, or there would be further trouble of a like character. To the question, "Why?" reply, taking up a bottle of red wine to point your witticism, "would it not be a second difficulty with the Porte, you geese?" To make the jest perfect, connect Turkey in Europe with the dindon aux marrons, of which you will have just partaken.

The Weather.—If forced to fall back upon this venerable subject (which should only be broached in the wilds of Cornwall, or other equally primitive spots), of course you can speak of a hard frost being "an ice day for a hunting-man, although he is sure to swear at it." If the weather breaks, you may observe, "You thaw so," but not when you have to shout the quibble through the ear-trumpet of a deaf old maid. And this, with the other witticisms recorded above, should carry you (by desire) into the middle of next week.

A DEADLY KISS.—The Hotch-kiss.

Tax-gatherers molest one's door,

The streets are choked with messy mist;

I'm the proverbial Bachelor,

An old, prosaic Pessimist.

Yet somehow—who can tell me why?—

Urged by the Past's dim Phantom, I'm

Disposed my cosy Club to fly,

And prank it at the Pantomime.

A Phantom weird of things forgot!

My mother, proud of me at her

Sweet side—our yellow chariot—

The long, long drive—the theatre—

My fear to miss—my thrill when in—

The Fairy Queen, the jolly King—

The laughter flung at Harlequin,

And Pantaloon arollicking.

And sister PRUE, and brother TIM,

(I scarcely recollected them),

Magnificent in gala trim:

Dear me, how I respected them!

I deemed them quite grown up, so bold

Seemed they, glared so defiantly:

Yet they, too, cowered to behold

Prone before JACK the Giant lie.

Yes! Where is TIM, where PRUE, alack!

Where mother fondly pliant now?

Where for that matter too is JACK,

And where the grisly Giant now?

In lonely stall, with vacant brow

I sit and eye the coryphées:

In my time they were Fairies; now

They seem to me but sorry fays.

The pageantry is twice as grand,

The wealth of wealth embarrasses;

And yet this is not elfinland

But great AUGUSTUS HARRIS's.

The blasé children vote it flat,

When Mister Clown cries, "Here's a go!"

Yes, there's the box where erst we sat

And laughed so, sixty years ago.

The very box: I think, you know,

The reason I'm so queer to-night

Is merely because long ago

Here faces were not here to-night.

I'd best be off—Bless me! no Clown?

No Stage?—no Past invidious?

No Orchestra?—but simply BROWN

Snoring the midnight hideous!

No Drury Lane?—no tinsel flare?—

No pirouetting Bogeydom?—

Only a Club, and one who there

Forgot in sleep his Fogeydom!

Welcome my Transformation Scene;

I'm dull once more, and every

Old Bachelor like me, I ween,

May muse at times his reverie.

NOTICE.—Rejected Communications or Contributions, whether MS., Printed Matter, Drawings, or Pictures of any description, will in no case be returned, not even when accompanied by a Stamped and Addressed Envelope, Cover, or Wrapper. To this rule there will be no exception.