*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 12681 ***

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Us and the Bottleman, by Edith Ballinger

Price, Illustrated by Edith Ballinger Price

US

and

THE BOTTLE MAN

BY

EDITH BALLINGER PRICE

Author of “SILVER SHOAL LIGHT,”

“BLUE MAGIC,” etc.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

BY THE AUTHOR

1920

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

US AND THE BOTTLE MAN

CHAPTER I

It began with Jerry’s finishing off all the

olives that were left, “like a pig would

do,” as Greg said. His finishing the olives

left us the bottle, of course, and there is

only one natural thing to do with an empty

olive-bottle when you’re on a water picnic.

That is, to write a message as though you

were a shipwrecked mariner, and seal it up

in the bottle and chuck it as far out as ever

you can.

We’d all gone over to Wecanicut on the

ferry,—Mother and Aunt Ailsa and Jerry

and Greg and I,—and we were picnicking

beside the big fallen-over slab that

looks just like the entrance to a pirate

cave. We had a fire, of course, and a lot

of things to eat, including the olives, which

were a fancy addition bought by Aunt

Ailsa as we were running for the ferry.

When we asked her if she had any paper,

she tore a perfectly nice leaf out of her

sketch-book, and gave me her 3 B drawing-pencil

to write with. It was very soft, and

the paper was the roughish kind that

comes in sketch-books, so that the writing

was smeary and looked quite as if shipwrecked

mariners had written it with

charred twigs out of the fire. We’d

done lots of messages when we were on

other water picnics, but we’d never heard

from any of them, although one reason

for that was that we never put our address

on them. We decided we would this time,

because Jerry had just been reading about

a fisherman in Newfoundland picking up

a message that somebody had chucked

from a yacht in the Gulf of Mexico months

and months before.

I wrote the date at the top, near the raggedy

place where the leaf was torn out

of Aunt Ailsa’s sketch-book, and then I

put, “We be Three Poore Mariners,” like

the song in “Pan-Pipes.”

Jerry and Greg kept telling me things to

write, till the page was quite full and went

something like this:

“We be Three Poore Mariners, cast away upon the lone and

desolate shore of Wecanicut, an island in the Atlantic Ocean, lat.

and long. unknown. Our position is very perilous, as we have

exhausted all our supplies, including large stores of olives, and

are now forced to exist on beach-peas, barnacles,

and—and—”

“Eiligugs’ eggs,” said Greg, dreamily.

Jerry pounced on him and said they only

grew on the Irish coast, but I said:

“All right! Beach-peas, barnacles, and

eiligugs’ eggs, of which only a small supply

is to be had on this bleak and dismal

coast. Our ship, the good ferry-boat

Wecanicut, left us marooned, and there is

no hope of our being picked up for the next

two hours. Any person finding this message,

please come to our assistance by

dropping us a line,” (I must honestly say

that this was Jerry’s, and much better than

usual) “as the surf is too heavy for boats

to land on this end of the island.

Signed:—”

“Don’t sign it ‘Christine’,” Jerry

said. “Put ‘Chris,’ if we’re to be real

mariners.”

So I put “Chris Holford, æt. 13,” which I

thought might look more dignified and scholarly than

“aged,” and Jerry wrote “Gerald M. Holford,”

and put “æt. 11” after it, but I’m sure he

didn’t know what it meant until I did it. Then we stuck

the paper at Greg, and he stared at it ever

so long and finally said:

“Ate eleven! He ate lots more than

that; I saw him.”

Jerry pounced again,—I was laughing

too hard to,—and said:

“It’s not olives, silly; it’s an abbreviated

French way of saying how old we

are.”

Then I had to pounce on him, and tell

him it was Latin, as he might know by the

diphthong. By that time Greg had written

“Gregory Holford, Ate 8,” across the

bottom, very large, and Jerry said he

might as well have put 88 and had done

with it. We folded the paper up in the

tinfoil that the chocolate came in and

jammed it into the bottle and pounded the

cork in tight with a stone. Greg was all

for chucking it immediately, but Jerry said

it would have a better chance if we

dropped it right into the current from the

ferry going home. So we cocked the bottle

up on a rock and went back to the

pirate-cave-entrance place to finish a

game of smugglers.

Wecanicut is a nice place to smuggle

and do other dark deeds in, and I don’t believe

we’ll ever be too old to think it’s

fun. This time we cut the rest of the tinfoil

into roundish pieces with Jerry’s jackknife,

and stowed them into a cranny in

the cave. They shone rather faintly and

looked exactly like double moidores, except

that those are gold, I think. We also

borrowed Aunt Ailsa’s hatpin with the

Persian coin on the end. By running the

pin down into the sand all the way, you

can make it look just like a goldpiece lying

on the floor of the cave. She is a very

obliging aunt and doesn’t mind our doing

this sort of thing,—in fact, she plays lots

of the games, too, and she can groan more

hollowly than any of us, when groans are

needed.

This time we didn’t ask her to, because

she was reading a book by H. G. Wells to

Mother, and anyway all our proceedings

were supposed to be going on in the most

Stealthy and Silent Secrecy. The moidores

and the Persian coin were all that

was left of an enormous lot of things

which the villainous band had buried,—golden

chains, and uncut jewels, and pots

of louis d’ors, and church chalices (Jerry

says chasubles, but I think not). Greg

and Jerry had dragged all these things up

from the edge of the water in big empty

armfuls, and we stamped the sand down

over them. It really looked exactly as if

the tinfoil moidores were a handful that

was left over. Greg was just giving the

final stamp, when Jerry crooked his hand

over his ear and said:

“Hist, men! What was that?”

They were having artillery practice

down at the Fort, and just then a terrific

volley went sputtering off.

“’Tis a broadside from the English vessel!”

Jerry said. “We are pursued!”

We crept out from the cave and made

off up the shore as fast as possible. Jerry

went ahead and jumped up on a rock to

reconnoiter. He did look quite piratical,

with my black sailor tie bound tight over

his head and two buttons of his shirt undone.

Greg had his own necktie wrapped

around his head, but several locks of hair

had escaped from under it. He always

manages to have something not quite right

about his costumes. He has very nice

hair—curly, and quite amberish colored—but

it’s not at all like a pirate’s. I poked

him from behind to make him hurry, for

Jerry was pointing at a big schooner that

was coming down the harbor. We all lay

down flat behind the rock until she had

gone slowly around the point. We could

see the sun winking on something that

might have been a cannon in her waist—that’s

the place where cannon always are—and

of course the captain must have

been keeping a sharp lookout landward

with his spy-glass.

“Eh, mon,” said Jerry, when the schooner

had passed, “but yon was a verra close

thing!”

That’s one of the worst things about

Jerry,—the way he mixes up language.

We’d been reading “Kidnapped,” and I

suppose he forgot he wasn’t Alan.

“Silence, dog!” I said, to remind him

of who we were. “Very like she’s but

hove to in the offing, and for aught you

know she’s maybe sending ashore the

jolly-boat by now.”

“Then let’s go to the end of the point

and have a look,” Greg suggested.

He doesn’t often make speeches, because

Jerry is apt to pounce on him and

tell him he’s “too plain American,” but I

think it isn’t fair, because he hasn’t read

as many books as Jerry and I. So I hurried

up and said:

“Bravely spoke, my lad; so we will, my

hearty!” And we crawled and clambered

along till we came to the end of the point

where it’s all stones and seaweed and big

surf sometimes. The surf was not very

high this time,—just waves that went

whoosh and then pulled the pebbles back

with a nice scrawpy sound. The schooner

was half-way down to the Headland, not

paying any attention to us.

“Ah ha!” Jerry said, “safe once more

from an ignominious death. But, Chris,

look at the Sea Monster! What’s happened

to it?”

The Sea Monster is a bare black rock-island

off the end of Wecanicut. We

called it that because it looks like one, and

it hasn’t any other name that we know of.

We’d always wanted awfully to go out

there and explore it, but the only time we

ever asked old Captain Moss, who has

boats for hire, he said, “Thunderin’ bad

landin’. Nothin’ to see there but a clutter

o’ gulls’ nests,” and went on painting the

Jolly Nancy, which is his nicest boat.

But the thing that Jerry was pointing

out now was very queer indeed. It was

just a little too far away to see clearly

what had happened, but it seemed as if a

piece of rock had fallen away on the side

toward us, leaving a jaggedy opening as

black as a hat and high enough for a person

to stand upright in.

“The entrance to a subaground tunnel!”

Greg shouted, leaping up and down in the

edge of a wave.

He will say “subaground,” and it really

is quite as sensible as some words.

“The entrance to a real pirate cave, you

mean!” said Jerry. “Glory, Chris, I really

shouldn’t wonder if it were. Captain

Kidd was up and down the coast here.

What if they buried stuff in there and

then propped a big chunk of rock up

against the hole?”

“I wish we had a telescope,” I said,

“though I don’t suppose we could see into

the blackness with it. Mercy, I wish we

could get out there! It’s more worth exploring

than ever.”

“Let’s tell Mother and Aunt!” said

Greg, and started running back down the

beach, shouting something all the way.

Mother said, “Nonsense!” and, “Of

course it’s a natural cave in the rock.

You probably only noticed it today.”

But she and Aunt Ailsa shut up the

H. G. Wells book and came to look. They

did think, when they saw it, that it was

something new. Aunt Ailsa thought it

looked very exciting and mysterious, but

she agreed with Mother that it was no sort

of place to go to in a boat.

“Just look at the white foam flinging

around those rocks,” she said; “and

there’s practically no surf on today.”

We had to admit that it wasn’t a nice-looking

place to land on from a rowboat,

but we did wish that we were hardy adventuring

men, bold of heart and undeterred

by grown-ups. We knew, too, that

Captain Moss would say, “Pshaw!” if we

told him there might be treasure on the

Sea Monster, and he certainly wouldn’t

risk the Jolly Nancy on those rocks in her

nice new green paint.

We were so much excited about the

Sea Monster suddenly having a big

black hole in it that we almost forgot to

take the bottle when we went home. We

did forget Aunt Ailsa’s hatpin, and Greg

had to run back for it, because he can run

faster than any of the rest of us, and

Captain Lewis held the ferry for him.

Everybody leaned out from the rail and

peered up the landing, because they

thought it must be a fire or the President

or something. They all looked awfully

disappointed when it was only Greg, with

the black necktie still around his head and

Aunt’s hatpin held very far away from

him so that it wouldn’t hurt him if he fell

down. He tumbled on board just as the

nice brown Portuguese man who works

the rattley chain thing at the landings was

pushing the collapsible gate shut, and

Greg gasped:

“I brought—the moidores—too!”

But Jerry collared him and pulled the

necktie off his head. Jerry hates to have

his relatives look silly in public, but I

thought Greg looked very nice.

We chucked the bottle overboard from

the upper deck, just when the Wecanicut

was halfway over. The nice Portuguese

man shouted up, “Hey! You drop something?”

but we told him it was just an

old bottle we didn’t want, and not to

mind. We watched it go bob-bobbing

along beside an old barrel-head that was

floating by, and we wondered how far it

would go, and if it would leak and sink.

The tide was exactly right to carry it outside,

if all went well.

“Perhaps,” said Greg, when we were

halfway up Luke Street, going home, and

had almost forgotten the bottle, “perhaps

it will land on the Sea Monster, and the

pirates will find it.”

“Glory!” said Jerry, “perhaps it will.”

CHAPTER II

Just in the middle of the rainiest week came the

thing that made Aunt Ailsa so sad. She read it in the newspaper, in

the casualty list. It was the last summer of the war, and there were

great long casualty lists every day. This said that

Somebody-or-other Westland was “wounded and missing.” We

didn’t know why it made her so sad, because we’d never

heard of such a person, but of course it was up to us to cheer her

up as much as possible. Picnics being out of the question, it had to

be indoor cheering, which is harder. Greg succeeded better than the

rest of us, I think. He is still little enough to sit on

people’s laps (though his legs spill over, quantities). He sat

on Aunt Ailsa’s lap and told her long stories which she seemed

to like much better than the H. G. Wells books. He also

dragged her off to join in attic games, and she liked those, too,

and laughed sometimes quite like herself.

Attic games aren’t so bad, though summer’s not the

proper time for them, really. There is a long cornery sort of closet

full of carpets that runs back under the eaves in our attic, and if

you strew handfuls of beads and tin washers among the carpets and

then dig for them in the dark with a hockey-stick and a pocket

flash-light, it’s not poor fun. Unfortunately, my head knocks

against the highest part of the roof now, yet I still do think

it’s fun. But Aunt Ailsa is twenty-six and she likes it, so I

suppose I needn’t give up.

The day Aunt Ailsa really laughed was when Greg rigged himself up

as an Excavator. That is, he said he was an excavator, but I never

saw anything before that looked at all like him. He had the round

Indian basket from Mother’s work-table on his head, and some

automobile goggles, and yards and yards of green braid wound over

his jumper, and Mother’s carriage-boots, which came just below

the tops of his socks. In his hand he had what I think was a

rake-handle—it was much taller than he—and he had the

queerest, glassy, goggling expression under the basket.

He never will learn to fix proper clothes. He might have seen

what he should have done by looking at Jerry, who had an old felt

hat with a bit of candle-end (not lit) stuck in the ribbon, and a

bandana tied askew around his neck. But Aunt Ailsa laughed and

laughed, which was what we wanted her to do, so neither of us

remonstrated with Greg that time.

Father plays the ’cello,—that is, he does when he has

time,—and he found time to play it with Aunt, who does piano.

I think she really liked that better than the attic games, and we

did, too, in a way. The living-room of our house is quite

low-ceilinged, and part of it is under the roof, so that you can

hear the rain on it. The boys lay on the floor, and Mother and I sat

on the couch, and we listened to the rain on the roof and the

sound—something like rain—of the piano, and

Father’s ’cello booming along with it. They played a

thing called “Air Religieux” that I think none of us

will ever hear again without thinking of the humming on the roof and

the candles all around the room and one big one on the piano beside

Aunt Ailsa, making her hair all shiny. Her hair is amberish, too,

like Greg’s, but her eyes are a very golden kind of brown,

while his are dark blue.

We thought she’d forgotten about being sad, but one night

when I couldn’t sleep because it was so hot I heard her

crying, and Mother talking the way she does to us when something

makes us unhappy. I felt rather frightened, somehow, and wretched,

and I covered up my ears because I didn’t think Aunt would

want me to hear them talking there.

The next day the sun really came out and stayed out. All of

us came out, too, and explored the garden. The grass had

grown till it stood up like hay, and there were such tall green

weeds in the flowerbeds that Mother couldn’t believe

they’d grown during the rain and thought they were some phlox

she’d overlooked. The phlox itself was staggering with

flowers, and all the lupin leaves held round water-drops in the

hollows of their five-fingered hands. Greg said that they were fairy

wash-basins. He also found a drowned field-mouse and a sparrow. He

was frightfully sorry about it, and carried them around wrapped up

in a warm flannel till Mother begged him to give them a military

funeral. Jerry soaked all the labels off a cigar-box, and then

burned a most beautiful inscription on the lid with his pyrography

outfit. Part of the inscription was a poem by Greg, which went like

this:

“O little sparrow,

Perhaps to-morrow

You will fly in a blue house.

And perhaps you will run

In the sun,

Little field-mouse.”

Jerry didn’t see what Greg meant by a “blue

house,” but I did, and I think it was rather nice. I copied

the poem secretly, before the cigar-box was buried at the end of the

rose-bed. I think Greg really cried, but he had so much black

mosquito netting hanging over the brim of his best hat that I

couldn’t be sure.

Fourth of July came and went—the very patriotic one, when

everybody saved their fireworks-money to buy W.S.S. with. We bought

W.S.S. and made very grand fireworks out of joss-sticks. Joss-sticks

have wonderful possibilities that most people don’t know

about. The three of us went down to the foot of the garden after

dark and did an exhibition for the others. By whisking the

joss-sticks around by their floppy handles you can make all sorts of

fiery circles. I made two little ones for eyes, and Greg did a nose

in the middle, and Jerry twirled a curvy one underneath for a mouth

that could be either smiling or ferocious. A little way off you

can’t see the people who do it at all, and it looks just like

a great fiery face with a changing, wobbly expression.

Then Greg did a fire dance with two sparklers. He dances rather

well,—not real one-steps and waltzes, but weird things he

makes up himself. This one lasted as long as the sparklers burned,

and it was quite gorgeous. After that we had a candle-light

procession around the garden, and the grown people said that the

candles looked very mysterious bobbing in and out between the trees.

We felt more like high priests than patriots, but it was very

festive and wonderful, and when we ended by having cakes and

lime-juice on the porch at half-past nine, everybody agreed that it

had been a real celebration and quite different.

In spite of being up so late the night before, Greg was the first

one down to breakfast next morning. Our postman always brings the

mail just before the end of breakfast, and we can hear him click the

gate as he comes in. This morning Jerry and Greg dashed for the mail

together, and Greg squeezed through where Jerry thought he

couldn’t and got there first. When they came back, Jerry was

saying:

“Let me have it, won’t you; it’ll take you all

day!” and dodging his arm over Greg’s shoulder.

“Messrs. Christopher, Gerald, and Gregory Holford; 17 Luke

Street,” Greg read slowly. Then he tripped over the threshold

and floundered on to me, flourishing the big envelope and

shouting:

“It’s funny paper, and it’s funny writing, and

I know it’s from The Bottle!”

“My stars!” said Jerry, with a final snatch.

But I had the envelope, and I looked at it very carefully.

“Boys,” I said, “I truly believe that it

is.”

CHAPTER III

The envelope was a square, thinnish one, addressed

in very small, black handwriting.

“It must be from The Bottle,” Jerry said;

“otherwise they wouldn’t have thought you were a boy and

put Christopher.”

I had been thinking just the same thing while I was trying to

open the envelope. It was one of the very tightly stuck kind that

scrumples up when you try to rip it with your finger, and we had to

slit it with a fruit-knife before we could get at the letter. There

were sheets of thin paper all covered with writing, and when Jerry

and Greg saw that, they both fell upon it so that none of us could

read it at all. I persuaded them that the quickest thing to do would

be to let me read it aloud, and as we’d finished breakfast

anyway, we each took our last piece of toast in our hands and went

out and sat on the bottom step of the porch. I read:

Fellow Adventurers and Mariners in

Distress:

By this time there may be naught left of you but a whitening

huddle of bones, surf bleached on the end of Wecanicut,—for I

know well what meager fare are eiligugs’ eggs and barnacles.

However, I take the chance of finding at least one of you alive, and

address you fraternally as a companion in distress.

I am myself stranded on a cheerless island where, against my

will, I am kept captive—for how long a time I cannot guess. I

was brought here at night, only forty-eight hours ago, and landed

from a vessel which almost immediately departed whence it had come,

into the darkness. My captors left me to go with the vessel, the

chief of them threatening to return every week to torment me unless

I obeyed his slightest command. I stand in great fear of this man,

who is tall and bearded, for he brings with him instruments of

torture and bottles containing, without doubt, poison.

Can you imagine my joy when, tottering down the beach this

morning, supporting my frame upon two sticks, I beheld your bottle

cast up on the sands? Now, thought I, I can unburden myself to these

three unfortunate men, obviously in even greater distress than my

own, and we can, perhaps, ease each other’s monotonous

maroonity. Scholars, too, I perceive you to be,—witness the

Latin following your signatures. Ah well, Grata superveniet quae

non sperabitur hora, as the poet so truly says, and I cannot

express to you how eager, how happy I am, in the thought of

communicating with some one other than the natives of this desolate

isle. These inhabitants, though friendly on the whole, are uncouth

and barbaric. They spend their entire time fishing from boats which

they build themselves, or squatting beside their huts mending their

fishing implements.

The good soul with whom I am lodging is calling me to my scanty

repast. In the rude language of the place she tells me that there is

“Krabss al ad an dunny.” How can I live long, I ask, on

such fare?

Hopefully, your

CASTAWAY COMRADE.

P.S. My

address—mail reaches me from time to time, by aforesaid

vessel—is P.O. Box 14, Blue Harbor, Me. ME stands for Mid

Equator, but the abbreviation is sufficient. Blue Harbor is my own

literal translation of the native Bluar Boor. Box 14 refers to the

native system of delivering messages. P.O. has, I think, something

to do with the P. & O. steamers, which, however, do not very

often touch here.

“I told you it would go around the world!”

Greg said, when I had finished, and Jerry and I were staring at each

other.

“Well!” Jerry said at last. “What

luck!”

“I should rather say so,” I said; “suppose a

fisherman had found it, or no one at all.”

“Bless his old heart,” said Jerry, taking the

letter.

I wanted to know why “old.”

“He must be ancient if he has to totter along on two

sticks,” Jerry said. “Besides, he has a stately,

professorish sort of style. Do you suppose he really does want us to

write to him?”

“Of course he does,” Greg said; “he tells us to

often enough. Think of being alone out there with savages, and that

bearded chief coming with poison bottles and all.”

“Shut up, Greg,” said Jerry; “you don’t

understand. There’s more in this than meets the eye, Chris. I

didn’t get on to this crab salad business when you read

it.”

Neither had I; in fact, I hadn’t got on to it until Jerry

said it in proper English.

“He’s a good sort, poor old dear,” I said.

“Why do you suppose they keep him out there?”

“He’s there of his own free will, right

enough,” Jerry said.

But I didn’t think so.

We were still confabbing over the letter, and explaining bits to

Greg, who was hopelessly mystified, when Mother came out to

transplant some columbine that had wandered into the lawn. We did a

quick secret consultation and then decided to let her in on the

Castaway. So we bolted after her and took away the trowel and showed

her the letter. She read it through twice, and then said:

“Oh, Ailsa must hear this, and Father!” But what we

wanted to know was whether or not we might write to the Castaway,

because we didn’t quite want to without letting her know about

it. She laughed some more and said, “yes, we might,” and

that he was “a dear,” which was what we thought.

We decided that we would write immediately, so Jerry dashed off

to Father’s study and got two sheets of nice thin paper with

“17 Luke Street” at the top in humpy green letters, and

I borrowed Aunt Ailsa’s fountain-pen, which turned out to be

empty. I might have known it, for they always are empty when you

need them most. Jerry, like a goose, filled it over the clean paper

we were going to use for the letter, and it slobbered blue ink all

over the top sheet. But the under one wasn’t hurt, and we

thought one page full would be all we could write, anyway. We took

the things out to the porch table, and Greg held down the corner of

the paper so it wouldn’t flap while I wrote. Jerry sat on the

arm of my chair and thought so excitedly that it jiggled me.

But minutes went on, and the fountain pen began to ooze from

being too full, and none of us could think of a single thing to

say.

“If we just write to him ourselves,—in our own form,

I mean,” Jerry said, “it’ll be stupid. And I

don’t feel maroonish here on the porch. We’ll have to

wait till we go to Wecanicut again, and write from there.”

I felt somehow the way Jerry did, so we put away the things again

and went out under the hemlock tree to talk about the Castaway. Greg

didn’t come, and we supposed he’d gone to feed a tame

toad he had that year, or something. The toad lived under the

syringa bush beside the gate, and Greg insisted that it came out

when he whistled for it, but it never would perform when we went on

purpose to watch it, so I don’t know whether it did or

not.

Under the hemlock is one of the best places in the garden for

councils and such. The branches quite touch the grass, and when you

creep under them you are in a dark, golden sort of tent, crackley

and sweet-smelling. You can slither pine-needles through your

fingers as you discuss, too, and it helps you to think. We thought

for quite a long time, and then I got out the letter and spread it

down in one of the wavy patches of sunlight, and we read it

again.

“Did you really think anybody’d find it?” Jerry

asked suddenly, and I told him I hadn’t thought so.

“Neither did I,” he said; “let alone such a

jolly old soul. Why, he’d be better than Aunt on a

picnic.”

“I do wonder why he has to stay there,” I said.

“Perhaps he’s a fugitive from justice,” Jerry

suggested; “or perhaps he’s a prisoner and the bearded

person comes out with Spanish Inquisition things to make him confess

his horrible crime.”

“He sounds like a person who’d done a horrible

crime, doesn’t he!” I said in scorn.

“Well, then,” said Jerry, who really has the most

inspired ideas for plots, “perhaps he’s an innocent old

man whose wicked nephews want to frighten him into changing his

will, leaving an enormous fortune to them. And they’re keeping

him on the island till he’ll do it.”

“Well, whatever it is,” I said, “I don’t

think he’s awfully happy somehow, and it’s nice of him

to write such a gorgeous thing.”

So we both decided that whether he was staying on the island of

his own free will, or in bondage, in any case it must be frightfully

dull for him and that our letter ought to be interesting and

cheerful.

Just then the hemlock branches thrashed apart and Greg crawled

under with pine-needles in his hair. He sat back on his heels and

blinked at us, because he’d just come out of the sunlight.

“I thought somebody ought to write to the Bottle

Man,” he said, “so I did.”

“Well, I never!” Jerry said.

Greg fished up a bent piece of paper from inside his jumper and

handed it to me.

“You can see it,” he said, “but not

Jerry.”

“As if I’d want to!” Jerry said; but he did,

fearfully.

Greg is the most unexpected person I ever knew. He’s always

doing things like that, when everyone else has given up.

I spread his paper out on top of the other letter, and he

sprawled down beside me, all ready to explain with his finger. What

with his dreadfully bad writing and the sunlight moving off the

paper all the time as the branches swayed, it took me ever so long

to read the thing. This is what it was:

Dear Bottle Man:

To-day we got your leter wich surprised us very much. Although I

kept hopeing and hopeing some body would find the bottle. We are not

so distresed now because we were picked up and now have toast and

other things beter than barnicles. I mesured from here to the

equater on the big map and it is an aufuly far way for the bottle to

go. Only I thought it would. I am sorry you are so imprisined on the

iland and please dont let the cheif with the beard poisen you

because we would like to hear from you agan. If there is tresure on

that iland I should think you could look for it and it would be

exiting. But prehaps there is none. We hope there is some on

Wecanicut. But it is hard to know sirtainly. Chris and Jerry are

going to do a leter. But I thought I would first. I hope the saviges

will be frendly allways.

Your respecfull comrade,

GREGORY HOLFORD.

P.S. None of us are Bones yet.

“Will it do?” Greg asked anxiously, when I folded it

up. His eyes grow very dark when he’s anxious, and they were

perfectly inky now. You never would have guessed that they were

really blue.

“It’ll do splendidly,” I said, for I did think

the Castaway man would like Greg’s letter tremendously.

“Better let me see it, my lad,” said Jerry, rolling

over among the pine-cones and sitting up.

Greg got his precious letter with a snatch and a squeak, and

scurried off with it. I pitched Jerry back on to the pine-needles,

because I knew he’d never let the thing go if he saw it.

“Oh, let him send it,” I said.

“It’s perfectly all right, and it will do the Bottle Man

heaps of good.”

But Jerry growled about “beastly scrawls” and

wasn’t pleased with me until supper-time.

Somehow we all began calling our island person the “Bottle

Man” after Greg did, for it seemed as good a name as any for

him, seeing that we didn’t know his real one. We read the

letter from him after supper to Aunt Ailsa, and she laughed and

liked it, and so did Father. We also asked Father what the Latin

meant, and he made a funny face and said he’d forgotten such

things, but then he looked at it again and told us it meant

something like this:

“The happy hour shall come, all the more appreciated

because it comes unexpectedly.”

So we went to bed thinking about our poor old Bottle Man

consoling himself out there on his island with Latin quotations.

CHAPTER IV

We all went to Wecanicut next day, which was a glorious one, and

when the food had disappeared we three walked up the point and wrote

to the Bottle Man from there. We’d decided that the paper with

“17 Luke Street” on it was much too grand for

“poore mariners” anyway, so we’d just brought

brownish paper that comes in a block. We told the Bottle Man how

wonderful we thought it was that he had found our message, and how

his letter had cheered our lonely watching for a sail. Also, how we

had been picked up and were returned now to Wecanicut of our own

will, seeking rich treasure. We described the “Sea

Monster” very carefully, and wrote about the black

cave-entrance-looking place that had happened, where no boat would

dare to venture. Jerry’s description of it was quite wild. He

dictated it to me above the shrieking of a lot of gulls which were

flying over us all the time. It went like this:

“The Sea Monster was quite terrific enough looking before,

like the slimy black head of something huge coming out of the water.

Now it looks as if it had opened a cavernous maw” (I’m

sure he nabbed that from some book) “as black as ink, ready to

swallow any unfortunate mariner which came near. Below the base of

this fearsome hole roars the cruel surf, ready to engulf a boat

which would never be seen more if it was once caught in this deadly

eddy.”

I thought “deadly eddy” sounded like Illiteration, or

something you shouldn’t do, in the Rhetoric Books, but Jerry

was much excited over his description. He sat on top of a rock,

pointing out at the Sea Monster like a prophet. He has quite black

hair which blows around wildly, and he looked very strange sitting

up there raving about the cavern. The letter was very long by the

time we’d put in everything, and we hoped the Bottle Man would

like it. Just before we signed it, I said:

“Do you think we’d better tell him I’m really

Christine and not Christopher?”

“No,” Jerry said; “put Chris, the way

you did before. He’s writing now as man to man. He might be

disgusted if he knew it was just a mere female.”

“Oh, thank you,” I said; but I did put

“Chris,” on account of our all being fellow

castaways.

When we’d finished the letter we walked a long way down the

other shore toward the Fort. The wind was blowing right, and we

could hear bits of what the band was playing and now and then

peppery sounds from the rifle practice. It’s not a very big

fort, but it squats on the other side of Wecanicut, watching the

bay, and real cannon stick out at loopholes in the wall. The ferry

really only goes to Wecanicut on account of the Fort, because

there’s nothing else there but a few farm houses and some ugly

summer cottages near the ferry-slip. The point from which you see

the Monster is not near the Fort or the houses at all, and is much

the wildest part of Wecanicut. When you’re standing on the

very end you might think you really were on a deserted island,

because you can look straight out to sea.

We cut back cross-country through the bay-bushes and the dry,

tickly grass to our usual part of Wecanicut, where the grown-ups

were just beginning to collect the baskets and things and to look at

their watches. We posted the letter on the way home, and Greg

jiggled the flap of the letter-box twice to make sure that it

wasn’t stuck.

It was that week that Jerry sprained his ankle jumping off the

porch-roof and had to sit in the big wicker chair with his foot on a

pillow for days. He hated it, but he didn’t make any fuss at

all, which was decent of him considering that the weather was the

best we’d had all summer. We played chess, which he likes

because he can always beat me, and also “Pounce,” which

pulls your eyes out after a little while and burns holes in your

brain. It’s that frightful card game where you try to get rid

of thirteen cards before any one else, and snatch at aces in the

middle, on top of everybody. Jerry is horribly clever at it and

shouts “Pounce!” first almost every time. Greg always

has at least twelve of his thirteen cards left and explains to you

very carefully how he had it all planned very far ahead and would

have won if Jerry hadn’t said “Pounce” so

soon.

Also, Father let Jerry play the ’cello, and he made

heavenly hideous sounds which he said were exactly like what the Sea

Monster’s voice would be if it had one. Just when we were all

rather despairing, because Dr. Topham said that Jerry mustn’t

walk for two days more, the very thing happened which we’d

been hoping for. Greg came up all the porch steps at once with one

bounce, brandishing a square envelope and shouting:

“The Bottle Man!”

It was addressed to all of us, but I turned it over to Jerry to

do the honors with, on account of his being a poor invalid and

Abused by Fate. He had the envelope open in two shakes, with the

complicated knife he always carries, and pulled out any amount of

paper. He stared at the top page for a minute, and then said:

“Here, Greg, this is for you. You can be pawing over it

while we’re reading the proper one.”

But I said, “Not so fast,” and “Let’s

hear it all, one at a time.”

So I took Greg’s and read it aloud, because he takes such

an everlasting time over handwriting and this writing was rather

queer and hard to read. This is his letter:

Respected Comrade Gregory Holford:

I am writing to you separately because you wrote to me

separately, and very much I liked your letter. I cannot tell you how

much relieved I am to hear that toast has been substituted for

barnacles in your diet. In the long run, toast is far better for a

mariner, however hardy he may be.

It is indeed a long way from Wecanicut to the Equator,—but

are you sure you measured to ME.—Mid Equator? It is

very different, you know. The bearded one is pleased with me and has

not brought his poison bottles of late, but thank you for not

wanting me to die just now. I do not know of any treasure in Bluar

Boor, but I refer you to the enclosed letter which tells something

of treasure elsewhere. I hope your search on Wecanicut, my dear sir,

will be richly rewarded.

Please note that I refer to natives, not savages.

There is a vasty difference; more than you perhaps might

suppose.

May I inscribe myself your most humble servant,

THE BOTTLE MAN.

P.S. I’m so glad your Bones are still where they

belong.

Greg was counting elaborately on his fingers,

and said:

“I believe he answered everything in my letter, but

please let me have it, because there are some things I need to work

out myself.”

“Now for the business,” Jerry said. “This must

be the whole sad story of his life,—there’s pages of it.

Coil yourself up comfortably, Chris, and I’ll fire

away.”

So I coiled up beside Greg on the Gloucester hammock, and Jerry

began to read.

CHAPTER V

From my desolate island refuge I salute the Intrepid

Trio! Good sirs, what you tell me of the “Sea Monster”

makes my flesh creep and my hair stir with terror. A murderous bad

place I should call it, and not one to trifle with. Yet it might

well be, as you think, that the sudden-appearing cavern is the mouth

of a pirate cave fairly bursting with treasure, and only now exposed

to the eyes of such daring adventurers as yourselves by a trick of

the elements. Strange things there be above and below the waters of

the world—which serves to remind me of a tale you might not

scorn to hear. You may take it or leave it, as you will, but at

least the penning of it will pass some of my hours of banishment in

a pleasant fashion.

In the year of grace 18— (I shudder to think how long ago)

I was a bold youth of perhaps the age of the valiant

Christopher.

Here Jerry paused to give a muffled hoot at me. I chucked a

hammock cushion at him, and he went on:

My father’s house stood on a rambling street in an old

waterside town, and from the windows of my room I could see the

topmasts of sailing ships thrusting upward above gray roofs. Small

marvel that my head should be filled with the ways of the sea and

the wonder of it, or that I should spend long hours dreaming over

books that told of adventures thereon. It was over such a book that

I was poring one summer’s evening as I sat in the library

bow-window. The breeze from the harbor came in and stirred the

curtains beside my head, and brought with it the last westering

ripple of sunlight and a smell of climbing roses. The book had

dropped from my hand and I was well-nigh drowsing, when I saw, as

plain as day, the queerest figure possible clicking open our garden

gate. He looked to be some sort of South American

half-breed,—swart face under rough black hair, and striped

blanket gathered over dirty white trousers. Now I had seen many a

strange man disembark from ships, but, never such a one as this, and

when I saw that he was coming straight toward my window, I was half

tempted to make an escape.

He leaned on the sill of the open casement with his dark face

just below mine and began to pour out, in halting English, a tale

which at first I had some trouble in understanding. The most that I

made of it was that he, and he alone, knew the whereabouts of a city

buried ages since under the sea and filled with treasure of an

unbelievable description. But you may imagine that even the hint of

such a thing was enough to set me all athrill, and I was not greatly

surprised at myself when I found that I was following the queer,

slinking figure down our bare little New England street.

He led me to a ship, an old brigantine heavy with age and

barnacles and hung about with the sorriest gray rags of canvas that

ever did duty for sails. No wonder that nine days out we lost our

fore tops’l. But stay; I fear I go too fast! For you must know

that I went aboard that brigantine, and once aboard I could not go

ashore again, partly because the strange, ill-assorted crew detained

me at every turn, and partly because the longing was so strong upon

me to see the things I had read of so often. And that night found me

still upon the vessel, nosing down to the harbor light, with the

lamps of my father’s house winking less and less brightly on

the dim shore astern.

Well, sirs, it would weary you to tell much of that voyage, and

besides, many’s the time you yourselves must have weathered

the Horn. For it was ’round Cape Stiff we went—no Panama

Canal in those days—and I served a bitter apprenticeship on

ice-coated yards, clutching numbly at battering sails frozen stiff

as iron. It was Peru we were bound for,—Peru where the

submarine city lay beneath uncounted fathoms waiting for us. The

captain and I were the only ones Acuma, the half-breed, had taken

into his confidence; all the others sailed on a blind errand,

trusting to the skipper, who was a shrewd man and severe. And the

brigantine wallowed around the Cape and toiled on and on up the

coast, and every day Acuma grew more restless; every day he cast

about the water with eyes that seemed to pierce to the very bottom

of the Pacific.

One day of blue sky and little breeze, when we were pushing the

brigantine with all sails set, Acuma flung himself at a bound to the

quarterdeck, and a moment later the skipper shouted quick orders

that the crew could not understand for the life of them. For to

heave the ship to, just when we all had been whistling for enough

breeze to give her something more than steerage way, seemed nothing

short of insane. Acuma climbed to the maintop and looked at the

coast of Peru with a telescope, and the captain took bearings with

his instruments.

It was Acuma and I who went over the side in diving suits, for no

others save the captain knew what we sought, as I have said. Down I

went and down, with the weight of water crushing ever more strongly

against me, till I stood upon the sea’s floor. That in itself

was quite wonderful enough—the green whiteness of the sand and

the strange, multi-colored forest of weed and coral through which my

searchlight bored a single, luminous pathway. But right ahead,

looming and wavering, seen for an instant, lost again when a deep

vibration stirred and swayed the water, shone the faintly golden

shape of a great portal. Acuma I had lost sight of, but I had no

need to ask him what lay before me. The wild pounding of my heart

told me that I stood at the gateway of the city that had been

covered a thousand thousand years ago by the unheeding sea. Leaning

at an angle against the tide, I struggled forward till the great

gate towered above me, its arch half lost in the green, swimming

shadow of the water. But as I flashed my light up across its

pillars, it answered with the shifting sparkle of gems crusted thick

upon it.

I walked then, breathless, into a street paved with rough silver

ingots, each one surely weighing a quintal, between tremulous shapes

of buildings which pointed lustrous towers upward through fathoms of

green water. It was many minutes before I dared enter one of those

great silent halls. Dragging my heavy leaden-soled boots, I pushed

through a shapely silver doorway, and a fish darted past me as I

entered. Who could imagine the wonder of that vast room! The mosaic

that covered the walls and ceilings was of gold and jewels, not

porphyry and serpentine, such as delight the wondering visitor to

Venice, but precious stones—rubies, sapphires, emeralds,

amethysts as richly purple as grape clusters, topaz as clear and

mellow as honey.

Behind a traceried grillwork lay heaped a mound of treasures such

as no human eye will ever see again. I lifted a little tree

fashioned all of gold,—each leaf wrought of the

metal—and strung with jewelled fruits on which ruby-eyed

golden birds fed. In despairing rapture I clutched after a neck

ornament hung with pendulous pearls as large as plums. But as I

reached for it, I felt that something was looking at me from the

corner. Not Acuma; no human being was in sight. Peering out through

the glass visor of my helmet, I saw fixed on me from low down beside

the doorway two inky, moveless eyes as large as saucers. They were

not human eyes, nor did they belong to any sea creature I had ever

beheld or read of. They were round and fixed, pools of bottomless

blackness, staring at me through two varas of clear, swaying water.

I took an uncertain step backwards, and as I did so I felt something

soft and heavy laid slowly and slimily upon my shoulder....

Ah me, here is an interruption! A native child approaches,

bearing as an offering a Lol Ipop (one of the native fruits). Just

before he reaches me he falls face down, doubtless out of respect

for my gray hairs, and, on arising, proffers me the Lol Ipop, now

coated with sand. In this state I am expected to eat it, and, being

in great awe and fear of the inhabitants, I proceed to do so, which

incapacitates me for further epistolatory effort.

So, till I recover from the effects of my enforced meal, believe

me your devoted correspondent,

THE BOTTLE MAN.

“Well, of all mean tricks!” Jerry said.

“It’s worse than a continued story,” I said.

“Bother the horrid native child! Do you suppose that’s

really why he stopped?”

“Probably not; he knew it was the excitingest place to

stop. What did I tell you about his being ancient? Now he

says he has gray hairs, so that proves it.”

“I should think he might,” I said, “after such

experiences. What do you think it could have been that stared at

him?”

“An octopus, most likely,” Jerry said. “They

have goggly black eyes; I’ve read it.”

“But he said he’d never seen such eyes on any sea

beast he knew of, and he’s read as much as you have;

that’s sure.”

“That treasure! Oh, my eye!” Jerry sighed. “Do

you suppose he brought home hunks of it?”

“Just the same hunks that we dig up on Wecanicut, I

suppose,” I said.

“You mean you think he’s making up the whole

yarn?” Jerry asked. “Well, even if he is, it’s a

mighty good one, and it might have happened to him, at

that.”

Greg looked up suddenly from beside me, and said:

“I think the thing what stared at him was a

mer-person.”

“My child,” said Jerry, “I believe you’re

right.”

CHAPTER VI

Next day Jerry was well enough to walk around with

a cane, and when he’d broken Father’s second-best

malacca stick by vaulting over the box border with it, we decided

that he was quite all right, and the summer went on again as usual.

Of course we wrote to the Bottle Man at once, and told him, as

respectfully as we could, just what we thought of him for letting

the native child interrupt him in such an exciting part. We also

begged him to write again as soon as possible, and to choose a place

where the inhabitants weren’t likely to come with offerings.

We kept waiting and waiting, and no letter came, so we settled

ourselves to Grim Resignation, as Jerry said. It was worse than

waiting for the next number of a serial story, because you’re

pretty certain when that will come, but we had no idea how long it

would be before the Bottle Man wrote to us.

Aunt Ailsa still needed cheering up a good deal, and that kept us

busy. The cheering was great fun for us, because it consisted mostly

of picnics and long, long walks,—the kind where you take a

stick and a kit-bag and eat your lunch under a hedge, like a tinker.

We also wrote a story which we used to put in instalments under her

plate at breakfast every other day. We took turns writing the story,

and Greg’s instalments always made Aunt Ailsa the most cheered

up of all. The story was much too long to put in here, and rather

ridiculous, besides.

By this time it was almost September, and asters were beginning

to bloom in the garden and the hollyhocks were almost gone.

Wecanicut was turning the dry, russetty color that it does late in

the summer, and the harbor seemed bluer every day. Captain Moss took

us out in the Jolly Nancy one afternoon just for

kindness—we didn’t hire her at all. She is a

sixteen-footer and quite fast, in spite of being rather broad in the

beam. He let each of us steer her and told us a great many names of

things on her, which I forgot immediately. Jerry always remembers

things like that and can talk about reef-cringles and topping-lift

as if he really knew what they were for. We went quite far out and

saw the Sea Monster from a different side in the distance, and

tacked down to the other end of Wecanicut under the Fort guns.

It was when we got in from the gorgeous sail, with Greg carrying

the little basket all made of twisted-up rope Captain Moss had done

for him, that we found a big, square envelope lying on the hall

table. And, to our despair, supper was just ready and we

couldn’t read the letter till afterward. Supper was good, I

must admit,—baked eggs, all crusty and buttery on top, and

muffins, and cherry jam. We ate hugely, because of the Jolly

Nancy making us so hungry.

When we’d finished we went into Father’s study, where

he wasn’t, and turned on the desk-light and got at the letter.

I read it, while the boys crouched about expectantly. Here it

is:

Dear Comrades:

I should have answered your frantic appeals for news of me long

since, had I not been slavishly occupied in carrying out the demands

of the Man of Torture from whom I am now completely released,

praises be. I am even contemplating escape from Bluar Boor by

stealth. But no doubt you have no desire for these modern details

and are all agog to find out whether or not I met a wretched death

at the bottom of the sea. I think you left me—or I left

you—with a soft and hideous something resting upon my

shoulder.

Sirs, it was a Hand, a webbed hand, and turning, I looked

straight down into another pair of flat dark eyes. They belonged to

a creature not as tall as I, and certainly not human in shape. Arms

and legs it had, of a sort, and scales, also, and finny spines, and

a soft slimy body. Then, through the door which led to the silver

street, I saw more of the creatures, and more,—a soft,

hurrying crowd patting over the ingot blocks which paved the road,

peering in at the door, beckoning with webby fingers.

My helmet smothered the cry I gave as I struggled against the

horrible resistance of the water toward the door. Out in the street

the mer-crowd surrounded me, fingered my arms, looking at me with

unfathomable, disc-like eyes, black as ink. With dawning

comprehension it came over me that these creatures inhabited the

desolate, sea-filled city, lived in the mighty golden halls that

once had echoed to the footsteps of Peruvian kings, fared about the

rich streets where coral now grew instead of tree and flower.

The things were speechless, with no seeming means of

communication, and I saw, too, that they could not leave the

sea-bottom, but walked upon it as we do upon earth, and could no

more rise than we can leap into the air and swim upon it. I tried to

push my difficult way through the clinging swarm, who seemed

friendly enough in a weird, inhuman way, but I could not pass

through. Dimly through the swinging water I could see others coming

from every carven doorway down the silent street. I thought then of

the weights attached to me, and I decided to cut them loose at once

and rise from the ghostly place, of which I had seen quite enough to

suit me. But I determined to take with me at least one thing from

the vast mounds of treasure which held me breathless with utter

bewilderment.

So I turned and with my long knife began prying from its doorway

a ruby as large as my fist. Instantly, without warning, the creature

nearest me raised its scaly hand in a flinging gesture, and I felt a

hot and rushing pain just above my right elbow. I felt, too, a

coldness of water spurting down my arm and clutched wildly at the

sleeve of my diving-suit to seal the little hole which I saw in it.

Holding it tightly with my left hand, I slashed with my right at the

creatures who were now moving upon me menacingly, pressing me close.

If they forced me back into the doorway, all hope would be gone. I

cut desperately at the fastenings that secured the weights; felt

myself rising; felt my legs pull out from the clinging, slimy arms;

looked down at them—a sea of bobbing smooth heads, of round,

expressionless, black eyes; saw them waving their tentacle-like arms

in fury; saw at last the dim, golden crest of the tallest tower

below my feet; burst above the blessed sea-level and saw good blue

waves slapping the bow of the brigantine drifting lazily down toward

me.

I know nothing of the voyage home. I must have been poisoned by

the missile, whatever it was, that the sea-creature flung at me. (I

bear the scar to this day.) For I have no recollection of much more,

until I sat in the library bow-window of my father’s house,

very tired and stiff and thoroughly thankful that the voyage was

over. It was dark, and my mother sat sewing beside a shaded lamp and

singing to herself. I fingered the book that lay beside me, on the

window-seat, and said:

“Mother, did you keep the book just here all the time I was

gone because you were sorry I went and wanted to remember

me?”

She laughed, and said: “Yes, all the time while you were

sailing to the Port of Stars. Come now to supper, my

dear.”

So I got up very stiffly, for I felt weak and dizzy still, and

went with her. I said:

“I’m sorry, Mother, that after all I couldn’t

bring you any of the jewels.”

Whereupon she laughed again and said something about

“Cornelia” which I am too modest to repeat, but which,

being scholars, you will know by heart, and said that she was glad

enough to have me back at all.

Sirs, you cannot think how beautiful our little dining-room

looked to me, with the old brass-handled highboy in the corner and

the pots of flowers on the sill—far more beautiful than the

fretted golden towers and gem-girdled walls of the City under the

Sea.

So take my advice, young sirs, the advice of a man many years

older than you bold young blades: don’t you ever go listening

to a half-breed Peruvian that comes slinking to your window, no

matter how enticing may be his tales of treasure.

Your most faithful

BOTTLE MAN.

“Do you think he dreamed it?” Jerry said.

“Whatever it was, he must have been glad to get

back,” I said, switching off the light so that we could talk

in the dark, which is more creepy and pleasant.

“But the treasure!” Jerry said. “Do you suppose

there ever was such treasure in the world? That’s something

like! Imagine finding gold trees and birds eating jewels on the Sea

Monster! By the way, do you know about

‘Cornelia’?”

I said I thought she had something to do with sitting on a hill

and her children turning to stone one after the other, but Jerry

said that was Niobe and that it was she who turned to stone, not the

children. He has a fearfully long memory. So we put on the light

again and looked it up in “The Reader’s Handbook,”

because we didn’t want to bother the grown-ups, and we found,

of course, that she was the Roman lady who pointed at her sons and

said, “These are my jewels!” when somebody asked her

where her gold and ornaments were. So naturally the Bottle Man

didn’t feel like repeating such a complimentary thing, being

an un-stuck-up person, but we did think it was nice of his

mother.

We put away the “Handbook” and made the room dark

again and were arguing over all the exciting places in the Bottle

Man’s story, when Greg spoke up suddenly from the corner where

we’d almost forgotten him.

“If I found a thing like those mer-persons,”

he said drowsily, “I wouldn’t let it bite me. I’d

keep it in the bath-tub and teach it how to do things.”

“Like your precious toad, I suppose,” said Jerry.

“Don’t be idiotic.”

So we all went to bed, and I, for one, dreamed about all kinds of

glittering treasures and heaps of jewels each as big as your hat,

and of our nice old Bottle Man, with his long white beard flowing in

the wind.

*

*

* *

*

And

now comes the perfectly awful part.

CHAPTER VII

I must say at the beginning that it was all my

fault. Jerry says that it was just as much his, but it wasn’t,

because I’m the oldest and I ought to have known better. To

begin with, Father had to go to New York to give a talk at the

American Architects’ League, or something, and Mother decided

to go with him. At the last minute Aunt Ailsa got a weekend

invitation from somebody she hadn’t seen for ages and went

away, too, which left us alone with Katy and Lena. Katy has been

with us next to forever and took care of Jerry and Greg when they

were Infant Babes, so that Mother never imagined, of course, that

anything could happen in two days. It wasn’t Katy’s

fault either.

The first day was foggy, and the garden dripped, so we went down

to call on Captain Moss, who lives near the ferry-landing. Besides

having boats for hire, he sells such things as fishing-tackle and

very strong-smelling rope, and sometimes salt herring on a stick.

The things he sells are all mixed up with parts of his own boats and

pieces of canvas and rope-ends, and curly shavings that skitter

across the floor when the wind blows in from the harbor. There is a

window at one end of his shop-place that goes all the way to the

floor, like a doorway, and it is always open. His shop is half on

the ferry-wharf so that the window hangs right over the water, very

high above it. It is quite a dizzyish place, but wonderful to look

out at. Far away you see boats coming in, and Wecanicut all flat and

gray, and then right below is nice sloshy green water with old boxes

and straws floating by, and sometimes horrid orange-peels that

picnic people throw in.

That afternoon Captain Moss was mending the stern of one of his

boats, and when we asked him what he was fitting on, he said:

“Rudder-gudgeons.”

He grunted it out so funnily that it sounded just like some queer

old flounder trying to talk, and we thought he was joking. But he

wasn’t at all. Sometimes he is very nice and tells us the

longest yarns about when he shipped on a whaler, but this time he

was busy and the rudder-gudgeons didn’t behave right, I think,

so he let us do all the talking. We told him a good deal about the

bottle, and also something about the city under the sea. He said he

shouldn’t wonder at it, for there was powerful curious things

under the sea. He also said he supposed now we’d be wanting to

hire the Jolly Nancy “fer to find submarine cities,

sence he wouldn’t let us have her to go a-stavin’ in her

bottom on them rocks off Wecanicut.”

We decided that he really didn’t want to be bothered, so we

went away presently. To soothe him, Jerry bought some of the dry

herring things and carried them home in a pasteboard box that said

“1/2 doz. galvanized line cleats. Extra quality” on the

lid. Lena cooked the herrings for supper, but I don’t think

she could have done it right, because they were quite horrid.

The second day was the perfectly gorgeous kind that makes you

want to go off to seek your fortune or dance on top of a high hill

or do anything rather than stay at home, however nice your own

garden may be. We agreed about this at breakfast, and I said:

“Let’s go to Wecanicut.”

We’d never gone to Wecanicut alone, but I couldn’t

see any reason why we shouldn’t. Captain Lewis, on the ferry,

always watches over every one on board with a fatherly sort of eye,

and Wecanicut itself is a perfectly safe, mild place, without any

quicksands or tigers or anything that Mother would object to.

“I tell you what,” Jerry said, “let’s

make it a real adventure and take some costumes along. We never had

any proper ones there before.”

I thought this was a rather good idea, and after breakfast we

went up to select things that wouldn’t be too bothersome to

carry, from the Property Basket.

“Is it to be pirates or smugglers or what?” Greg

asked, poking in the corner where he keeps his own special rigs.

“Explorers, my fine fellow,” Jerry said,

“exploring after a submerged city.”

“Oh!” Greg said, evidently changing his ideas.

Jerry and I went down to ask Katy to make us some lunch.

“Just food; nothing careful,” Jerry explained.

“What are ye goin’ to do with it?” Katy

asked.

Jerry was all ready to say, “Eat it, of course,” but

I saw what Katy meant and said:

“We’re going out; it’s such a nice day. We

thought we’d take our lunch with us to save Lena

trouble.”

“Don’t get streelin’ off too far,” Katy

said, “Where are ye goin’?”

“Oh, down by the shore,” I said, which was not quite

the whole truth, because of course it was not our shore, but the

shore of Wecanicut I meant. Yes, all of it was my fault.

Just as we were putting the lunch into the kit-bag Greg came

staggering downstairs, trailing along the weirdest lot of stuff

he’d collected.

“What on earth is all that?” Jerry asked him.

“Drop it and get your hat.”

“It’s—my costume,” Greg explained, out of

breath from having dragged all the things down from the attic.

“Glory!” Jerry said, “You don’t suppose

you’re going to lug all that rubbish on to the ferry, do you?

Not while I’m with you, my boy.”

“You couldn’t begin to put on half of it,

Gregs,” I said. “Let’s weed it out a

little.”

“And look sharp about it,” Jerry said,

jingling the money for the ferry in his pocket.

Greg finally took a Turkish fez thing, and a black-and-orange

sash, and a white brocade waistcoat that Father once had for a

masque ball ages ago. We hadn’t time to tell him that it was

no sort of outfit for an explorer, so we bundled the things up with

our own and stuffed them all into the kit-bag on top of the

lunch.

Luke Street has a turn in it just beyond our house, so neither

Katy nor Lena could have seen which way we went; anyhow, I think

they were both in the back kitchen, which looks out on the

clothes-yard. I thought perhaps we should have told Katy where we

were going after all, but Jerry said:

“Fiddlesticks, Chris; we’re not babies. I suppose

you’d like Katy to take us in a perambulator.”

This was horrid of him, but he made up for everything later

on.

Our Captain Lewis was not in the pilot-house of the

Wecanicut. Instead there was a strange captain, a scraggly,

cross-looking person, staring at a little book and not watching the

people who came on board, the way Captain Lewis does. Jerry and I

sat on campstools on the windy side, and Greg went to watch the

walking-beam, which he thinks will some day knock the top off its

house. It always stops and plunges down just when he thinks it

surely will forget and go smashing on up through the roof. He is

quite disappointed that it never does. It behaved perfectly properly

this time and paddled the old ferry-boat over to Wecanicut as

usual.

We went up the hot little road that goes from the landing, and

then ran through a prickly, stony short-cut that leads among wild

rose-bushes and sweet fern to our part of the shore. There were tiny

little wavelets splashing over the rocks, and you couldn’t

think which was bluer—the sea or the sky. The first thing we

did was to bury our bottle of root-beer in a pool up to its neck and

mark the place with two white stones. This is something we have

learned by experience, for nothing is nastier than warm root-beer.

Then we put on the costumes and capered about a little. I had a

tight, striped football jersey, and my gym bloomers, and a black,

villainous-looking felt hat; and Jerry had a ruffle pinned on the

front of his shirt, and a wide belt with the big tinfoil-covered

buckle that Mother made for us once, and a felt hat fastened up on

the sides so that it looked like a real three-cornered one. Greg had

arrayed himself in his things, and he did look too absurd,

with more than a foot of the brocade waistcoat dangling below the

sash, the end of which trailed on the ground behind.

It gave us a queer, wild feeling, being there without the

grown-ups, and we decided to tell them that as we’d proved we

could do it, we might go again. We never did tell them that, as it

happens.

We all grew hungry so soon that we had lunch much earlier than

the grown-ups would have had it. The food Katy had fixed was

wonderful, though rather squashed on account of all the costumes

being on top of it in the kit-bag. While we ate we organized the

Submerged-City-Seeking-Expedition. Jerry was “Terry

Loganshaw,” in charge of the party, and I was

“Christopher Hole, shipmaster,” and Greg was

“Baroo, the Madagascar cabin-boy,” because we

couldn’t think of what else he could be, with such

clothes.

We tidied up all the picnic things so that there was nothing

left, and put the root-beer bottle into the kit-bag, because it was

a good one with a patent top. The kit-bag we took with us for

duffle, and we set off for the point. We went by the longest way we

could think of, to make it seem like a real

expedition,—’cross country and back again. Jerry led us

through the scratchy, overgrown part of Wecanicut, and we pretended

that it was a long, weary trek through the most poisonous

jungles to the coast of Peru; and when Greg walked right into a

spider’s web with a huge yellow spider gloating in the middle

of it, he said he’d been bitten by a tarantula. We told him

that we should have to leave him there to die, for we must press on

to the sea, but he cured himself by eating a magic sweet-fern leaf

and came running after us, tripping over his sash. The

trekking took a long time, and when we reached the end of the

point we were quite exhausted and flung our weary frames down on the

tropic sand to rest. All at once Jerry clutched my arm and said:

“Look yonder, Hole! Does not yon strange form appear to you

like the topper-most minaret of a sunken tower?”

He was pointing at the Sea Monster, and it really did look much

more like a rough sort of dome than a monster’s head. There

was a lot of haze in the air, which made it look bluish and

mysterious instead of rocky.

“It do indeed, sir,” I said. “Could it be that

city we be seeking?”

“Would that we had a boat!” said Greg, which might

have been quite proper if he’d been somebody else, instead of

Baroo.

We’d been sprawling on the sand again for quite a while,

when Jerry suddenly jumped up and shouted:

“Glory! Look, Chris!” not at all like Terry

Loganshaw.

I did look, and saw what he had seen. It was an empty boat, a

sort of dinghy, bobbing and butting along beside the rocks a little

way down the shore. We all ran helter-skelter, and Jerry pulled off

his shoes like a flash and waded out and pulled the boat in.

“It’s one of those old tubs from around the

ferry-landing,” he said. “It must have got adrift and

come down with the tide. Oars in it and all.”

We stood there silently, Jerry in the water holding the boat, and

we were all thinking the same thing. It was Greg who said it first,

quite solemnly.

“We could go out to the Sea Monster.”

Of course it was then that I ought to have said that we

couldn’t, but Jerry pulled the boat up the beach and ran back

to the end of the point to see how high the waves were before I

could say it. It was too late to say it afterwards, because when we

saw that there was not even the faintest curl of white foam around

the Sea Monster, it did seem as though we could do it.

“It’ll only take about five minutes to row out

there,” Jerry said, “and then we’ll have seen it

at last. It couldn’t be a better time. Why, a newly hatched

duckling could swim out there to-day.”

It did look very near, and the water was calm and shiny, with

just a long, heaving roll now and then, as if something underneath

were humping its shoulders.

So I said, “All right; let’s,” and we climbed

into the boat. Jerry rows very well, and he pulled both the oars

while I bailed with an old tin can that I found under the stern

thwart. The boat didn’t leak badly enough to worry about, but

I thought it might be just as well to keep it bailed. We talked in a

very nautical way, though Jerry kept forgetting he was Terry

Loganshaw and mixing up “Treasure Island” and Captain

Moss. But I didn’t feel so much like being Chris Hole, anyway,

even to please the boys, and I didn’t say much.

The Sea Monster was much further away than you might suppose.

When there was ever so much smooth, swelling water between us and

Wecanicut, the Monster’s head still seemed almost as far away

as before. Somehow the water looked very deep, although you

couldn’t see down into it, and it humped itself under the

boat.

CHAPTER VIII

Presently Wecanicut began to drop further away, and

then the Sea Monster loomed up suddenly right over us, and Jerry had

to fend the boat off with an oar. We had never guessed how big the

thing really was,—not big at all for an island, but very large

for a bare, off-shore rock. I should say that it was just about the

bigness of an ordinary house, and very black and beetling, with not

a spear of grass or anything on it. When Jerry said, “My

stars, what a weird place!” his voice went booming and

rumbling in among the rocks, and a lot of gulls flew up suddenly,

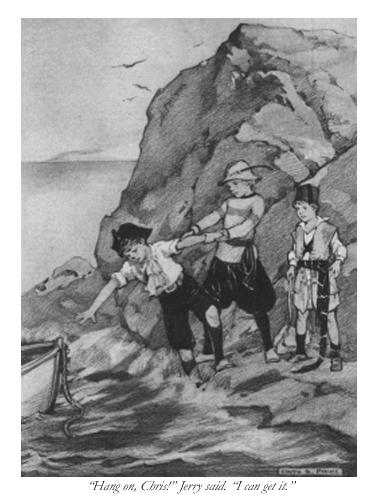

flapping and shrieking. He held the boat up against the edge of a

rock while Greg and I got out. We took the kit-bag ashore, and Jerry

made the boat fast by putting a big piece of stone on top of the

rope. There was nothing like a beach or even a shelving rock to pull

it up on, so that was the best we could do. The boat backed away as

far as it could, but the rope was firmly wedged between the rock and

the stone so it couldn’t get away.

Of course we went first to look at the black cave-entrance. Sure

enough, a great flat slab had fallen down from it and lay half in

the water,—we could see scratchy marks and broken places where

it had slid. The cave itself was about six feet deep, and very dank

and dismal-looking. There was no sign of there ever having been

treasure, for nobody could possibly have buried it, unless

they’d hewn places in the living rock, like ancient Egyptians.

We might have thought of that before, but of course we didn’t

honestly believe that there was treasure. Somehow the Sea Monster

didn’t seem nearly so jolly and exciting as it had from

Wecanicut. It was so real and big, and whenever a wave came in, it

boomed and echoed under the hanging-over rocks. We climbed around to

the other side and went up on top of the highest place, which was

about three times as high as I am. From there we could see the

Headland, very far away and blue, and Wecanicut behind us, safe and

green and friendly-looking, but a long way off; and nothing else but

a smeary line of smoke from a steamer at sea.

“We named this place well,” I said; “it

is a Monster.”

“Brrrr, hear it roar!” Jerry said. “The waves

must be bigger, or something. There weren’t any when we came

out.”

We looked down and saw that the water was behaving differently.

Instead of being smooth and rolling, there was a skitter of sharp

ripples all over it, and the waves went slap and frothed

white when they hit the rock. The sky had changed, too. It was not