The originality of the plot of The English Rose (the new play at the Adelphi) having been questioned, the following Scotch Drama is published with a view of ascertaining if it has been done before. Those of our readers who think they recognise either the situations or any part of the dialogue, will kindly remember that treatment is everything, and the imputation of plagiarism is the feeblest of all charges. The piece is called Telmah, and is written in Three Acts, sufficiently concise to be given in full:—

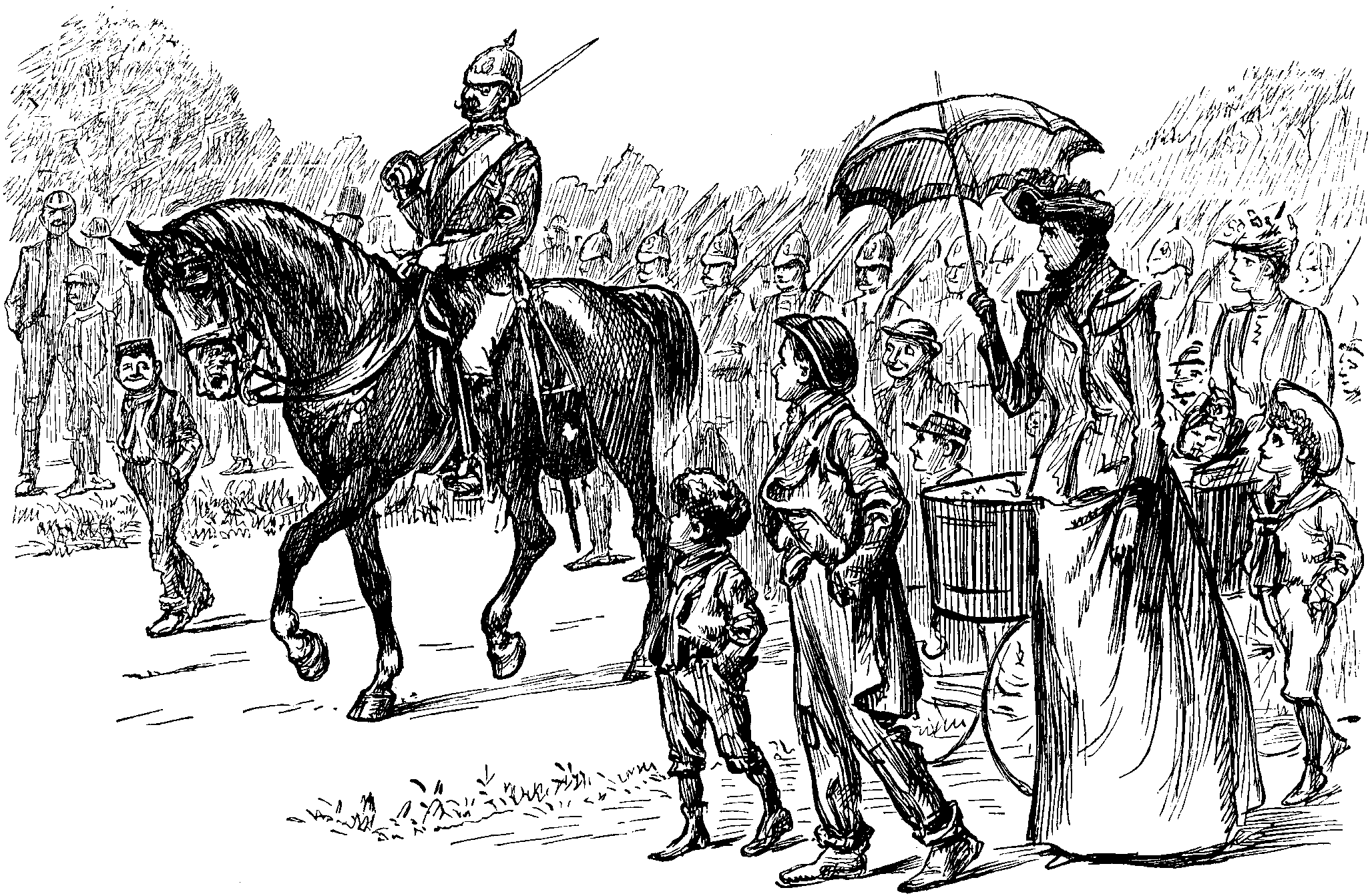

The Horse Guards Parade, Elsinore, near Edinburgh.

Enter MACCLAUDIUS, MACGERTRUDE, Brilliant Staff, and Scotch Guards. The Colours are trooped.

Then enter TELMAH, who returns salute of Sentries.

MacClaudius. I am just glad you have joined us, TELMAH.

Telmah. Really! I fancied some function was going on, but thought it was a parade, in honour of my father's funeral.

MacGertrude (with a forced laugh). Don't be so absurd! Your poor father—the very best of men—died months ago.

Telmah (bitterly). So long!

MacClaudius (aside). Ma gracious! He's in one of his nasty tempers, MACGERTRUDE. Come away! (Aloud.) Believe me, I shall drink your health to-night in Perrier Jouet of '74. Come!

[Exeunt with Queen and Guards.

Telmah. Oh! that this too solid flesh would melt! (Enter Ghost.) Hallo! Who are you?

Ghost (impressively). I am thy father's spirit! List, TELMAH, oh, list!

Telmah. Would, with pleasure, were I not already a Major in the Army, and an Hon. Colonel in the Militia.

Ghost (severely). None of your nonsense! (More mildly.) Don't be frivolous! (Confidentially.) I was murdered by a serpent, who now wears my crown.

Telmah (in a tone of surprise). O my prophetic soul! Mine uncle?

Ghost. Right you are! Swear to avenge me!

Telmah (after an internal struggle). I swear!

[Solo for the big drum. Re-enter troops, spectral effect, and tableau.

MacClaudius (aside to MACPOLONIUS). Lord Chamberlain, have you heard the argument? Is there no offence in't?

MacPolonius. Well, Sire, as I understand it is not intended for public representation, I have not done more than glance at it. I am told it is very clever, and called "The Mouse-trap."

MacGertrude. Rather an idiotic title! (Contemptuously.) "The Mouse-trap!"

[Business. A King on the mimic stage goes to sleep, and a shrouded figure pours poison into his ear. MACCLAUDIUS rises abruptly.

Telmah (excitedly). He poisons him for his estate. His name's MACGONZAGO. The story is extant, and writ in choice Italian. You shall see anon how the murderer gets the love of MACGONZAGO's wife!

MacClaudius (angrily to MACPOLONIUS). Chamberlain, we part this day month! Ma gracious! [Exit, followed by Queen and Court.

Telmah (exultantly). Now could I drink hot blood, and do such bitter business as the day would quake to look on!

Ghost (entering abruptly). Well, do it! What's the good of all this play-acting? Cut the ranting, and come to the slaughtering! (Seizes TELMAH by the arm.) If you are an avenger, behave as such!

[TELMAH greatly alarmed, sinks on his knees before Ghost, and the Curtain falls on the tableau.

Captain MacOsric, R.A. (Superintendent of the Circus). A hit, a palpable hit! (TELMAH and MACLAERTES engage a second time, and MACLAERTES wounds his opponent.) One to white! (Points out MACLAERTES with a small flag. Another round, when TELMAH wounds MACLAERTES.) One to black!

[Touches TELMAH with his flag.

MacClaudius (pouring out a glass of cheap champagne). Here, TELMAH, you are heated, have a drink!

Telmah. I'll play this bout first. Set it by awhile. (Aside to MAC-HORATIO, who smiles.) I know his cellar!

MacGertrude. I will take it for you, dear! (Impatiently.) Give me the cup? (Seizes it.) The Queen carouses to thy fortunes, TELMAH! [Drinks eagerly and with gusto.

MacClaudius (aside). The poisoned cup at eighteen shillings the dozen! It is too late! Ma gracious! [QUEEN dies in agonies.

MacLaertes. TELMAH, I am slain, and so are you—the foils are tipped with poison! (Speaking with difficulty.) Prod the old 'un!

[Dies.

Telmah. The point envenomed, too! Then venom do thy work!

[Stabs King and dies.

Ghost (entering in blue fire, triumphantly to MACCLAUDIUS). Now, you'll remember me! [MACCLAUDIUS dies.

[Soft music. Scene sinks, discovering magnificent funeral ceremony at the Abbey, Elsinore, near Edinburgh. A solemn dirge (specially composed for this new and original piece) is sung. Slow Curtain.

Antwerp.—Lots of Rubens, but the Harwich route is objectionable in "dusty" weather.

Boulogne.—Great attraction this year—Ex-Queen of NAPLES installed—but the port, at low tide, requires all the perfumes of Araby, and more.

Cologne.—Cathedral finished, but local scent is accurately expressed by "Oh!"

Dieppe.—Casino cheery, but the passage from Newhaven to French coast at times too terrible for words.

Etretat.—Amusing society, but the sanitary arrangements are rather shady.

Florence.—The Capital of Art, but at its worst in the dog days.

Geneva.—Within reach of Mont Blanc, but hotels indifferent, even when under "Royal Patronage."

Heidelberg.—Magnificent view from the Castle, but too many Cooks spoil the prospect.

Interlaken.—Jungfrau splendid, but not free from 'ARRIES and 'ARRIETTS.

Jerusalem.—Interesting associations, but travelling on mule-back is a trial to born pedestrians.

Kissingen.—Out of the beaten track, but query rather too much so.

Lucerne.—Lovely; but comfort takes a back seat if the Schweitzerhoff is full.

Madrid.—Plenty of pictures, but cholera in the neighbourhood.

Naples.—Famous Bay never off, but scarcely the place to face an epidemic.

Ouchy.—Beau Rivage beyond all praise, but environs uninteresting.

Paris.—Always pleasant—save in August.

Quebec.—Possibly attractive to the wildly adventurous, but scarcely worthy of a jaunt across the Atlantic.

Rome.—The City of the Popes and the Cæsars, but not to be thought of before the early winter.

St. Malo.—Quaint old Breton port, but journey from Southampton frequently dangerous, and always disagreeable.

Turin.—Typical Italian town; but why go here when other places are equally accessible?

Utrecht.—Suggestive of cheap velvet, but suggestive of nothing else.

Vevey.—Pleasantly situated, but triste to the last degree.

Wiesbaden.—Kept its popularity, in spite of its loss of roulette and trente et quarante; but Baden-Baden is preferable.

X les Bains.—Beautiful scenery, but population chiefly invalids.

Zurich.—Might do worse than go there; but, on the other hand, why not stay at home?

Polly (about 22; a tall brunette, of the respectable lower middle-class, with a flow of light badinage, and a taste for tormenting.)

Flo (18; her friend; shorter, somewhat less pronounced in manner; rather pretty, simply and tastefully dressed; milliner or bonnet-maker's apprentice.)

Mr. Ernest Hawkins (otherwise known as "ERNIE 'ORKINS"; 19 or 20; short, sallow, spectacled; draper's assistant; a respectable and industrious young fellow, who chooses to pass in his hours of ease as a blasé misogynist).

Alfred (his friend; shorter and sallower; a person with a talent for silence, which he cultivates assiduously).

POLLY and FLO are seated upon chairs by the path, watching the crowd promenading around the enclosure where the Band is playing.

Polly (to FLO). There's ERNIE 'ORKINS;—he doesn't see us yet. 'Ullo, ERNIE, come 'ere and talk to us, won't you?

Flo. Don't, POLLY. I'm sure I don't want to talk to him!

Polly. Now you know you do, FLO,—more than I do, if the truth was known. It's all on your account I called out to him.

Mr. Hawkins (coming up). 'Ullo! so you're 'ere, are you?

[Stands in front of their chairs in an easy attitude. His friend looks on with an admiring grin in the background, unintroduced, but quite happy and contented.

Polly. Ah, we're 'ere all right enough. 'Ow did you get out?

Mr. H. (his dignity slightly ruffled). 'Ow did I get out? I'm not in the 'abit of working Sundays if I know it.

Polly. Oh, I thought p'raps she wouldn't let you come out without 'er. (Mr. H. disdains to notice this insinuation.) Why, how you are blushing up, FLO! She looks quite nice when she blushes, don't she?

Mr. H. (who is of the same opinion, but considers it beneath him to betray his sentiments). Can't say, I'm sure; I ain't a judge of blushing myself. I've forgotten how it's done.

Polly. Ah! I dessay you found it convenient to forget. (A pause. Mr. H. smiles in well-pleased acknowledgment of this tribute to his brazen demeanour.) Did ARTHUR send you a telegraph?—he sent FLO one. [This is added with a significance intended to excite Mr. H.'s jealousy.

Mr. H. (unperturbed). No; he telegraphed to father, though. He's gettin' on well over at Melbun, ain't he? They think a lot of him out there. And now gettin' his name in the paper, too, like that, why—

Flo. That'll do him a lot of good, 'aving his name in the paper, won't it?

Mr. H. Oh, ARTHUR's gettin' on fine. Have you read the letters he's sent over? No? Well, you come in to-morrow evening and have a look at 'em. Look sharp, or they'll be lent out again; they've been the reg'lar round, I can tell you. I shall write and blow 'im up, though, for not sending me a telegraft, too.

Polly. You! 'Oo are you? You're on'y his brother, you are. It's different, his sending one to FLO.

Mr. H. (not altogether relishing this last suggestion). Ah, well, I dessay I shall go out there myself, some day.

[Looks at Miss FLO, to see how she likes that.

Flo. Yes, you'd better. It would make you quite a man, wouldn't it? [Both girls titter.

Mr. H. (nettled). 'Ere, I say, I'm off. Good-bye! Come on, ALF!

[Fausse sortie.

Polly. No, don't go away yet. Shall you take 'er out with you, ERNIE, eh?

Mr. H. What 'er? I don't know any 'er.

Polly (archly). Oh, you think we 'aven't 'eard. 'Er where you live now. We know all about it!

Mr. H. Then you know more than what I do. There's nothing between me and anybody where I live. But I'm going out to Ostralia, though. I've saved up 'alf of what I want already.

Polly (banteringly). You are a good boy. Save up enough for me too!

Mr. H. (surveying her with frank disparagement). You? Oh, lor! Not if I know it!

Flo (with an exaggerated sigh). Oh dear, I wish I was over there. They say they're advertising for maidservants—fifteen shillings a week, and the washing put out. I'd marry a prince or a lord duke, perhaps, when I got there. ARTHUR sent me a fashion-book.

Mr. H. So he sent me one, too. It was the Autumn fashions. They get their Autumn in the Spring out there, you know, and their Christmas Day comes in the middle of July. Seems rum, doesn't it?

Flo. He sent me his photo, too. He has improved.

Polly. You go out there, ERNIE, and p'raps you'll improve. [FLO giggles.

Mr. H. (hurt). There, that's enough—good-bye.

[Fausse sortie No. 2.

Polly (persuasively). 'Ere, stop! I want to speak to you. Is your girl here?

Mr. H. (glad of this opportunity). My girl? I ain't got no girl. I don't believe in 'em—a lot of—

Polly (interrupting). A lot of what? Go on—don't mind us.

Mr. H. It don't matter. I know what they are.

Polly. But you like Miss PINKNEY, though,—at the shop in Queen's Road,—you know.

Mr. H. (by way of proclaiming his indifference). Miss PINKNEY? She ought to be Mrs. SOMEBODY by this time,—she's getting on for thirty.

Polly. Ah, but she don't look it, does she: not with that lovely coloured 'air and complexion? You knew she painted, I dessay? She don't look—well, not more than thirty-two, at the outside. She spends a lot on her 'air, I know. She sent our GEORGY one day to the 'air-dresser's for a bottle of the stuff she puts on, and the barber sez: "What, do you dye your 'air?" To little GEORGY! fancy!

Mr. H. Well, she may dye herself magenter for all I care. (Changing the subject.) ARTHUR's found a lot of old friends at Melbun,—first person he come upon was a policeman as used to be at King Street; and you remember that Miss LAVENDER he used to go out with? (Speaking at FLO.) Well, her brother was on board the steamer he went in.

Polly. It's all right, FLO, ain't it? so long as it wasn't Miss LAVENDER herself! (To Mr. H.) I say, ain't you got a moustarsh comin'!

Mr. H. (wounded for the third time). That'll do. I'm off this time! [The devoted ALF once more prepares for departure.

Polly. All right! Tell us where you'll be, and we may come and meet you. I daresay we shall find you by the Outer Circle,—where the children go when they get lost. I say, ERNIE, look what a short frock that girl's got on.

Mr. H. (lingering undecidedly). I don't want to look at no girls, I tell you.

[pg 87]Polly. What, can't you see one you like,—not out of all this lot?

Mr. H. Not one. Plenty of 'ARRIETS! [Scornfully.

Flo. Ah! and 'ARRIES too. There's a girl looking at you, ERNIE; do turn round.

Mr. H. (loftily). I'm sure I shan't look at her, then. I expected a cousin of mine would ha' turned up here by now.

Polly. I wish he'd come. P'raps I might fall in love with him,—who knows?—or else FLO might.

Mr. H. Ah! he's a reg'lar devil, I can tell you, my cousin is. Why, I'm a saint to 'im!

Polly. Oh, I daresay! "Self-praise," you know!

Mr. H. (with a feeling that he is doing himself an injustice). Not but what I taught him one or two things he didn't know, when he was with me at Wandsworth. (Thinks he won't go until he has dropped one more hint about Australia.) As to Ostralia, you know, I've quite made up my mind to go out there as soon as I can. I ain't said nothing, but I've been meaning it all along. They won't mind my going at home, like they did ARTHUR's, eh?

Flo (in a tone of cordial assent). Oh no, of course not. It isn't as if you were 'im, is it?

Mr. H. (disappointed, but still bent on asserting his own value). You see, I'm independent. I can always find a berth, I can. I don't believe in keeping on anywhere longer than I'm comfortable. Not but what I shall stick to where I am a bit longer, because I've a chance of a rise soon. The Guv'nor don't like the man in the Manchester department, so I expect I shall get his berth. I get on well with the Guv'nor, you know, and he treats us very fair;—we've a setting-room to ourselves, and we can come and set in the droring-room of a Sunday afternoon, like the family; and I often have to go into the City, and, when I get up there, I can tell yer, I—

Flo (suddenly). Oh! there's Mother! I must go and speak to her a minute. Come, POLLY!

[Both girls rise, and rush after a stout lady who is disappearing in the crowd.

Alfred (speaking for the first time). I say, we'll 'ook it now, eh?

Mr. H. (gloomily accepting the situation). Yes, we'd better 'ook it.

[They "'ook it" accordingly, and Miss FLO and Miss POLLY, returning later, find, rather to their surprise, that their victim has departed, and their chairs are filled by blandly unconscious strangers. However, both young ladies declare that it is "a good riddance," and they thought "that ERNIE 'ORKINS never meant to go,"— which seems amply to console them for having slightly overrated their powers of fascination.

[The British "Cabby," hearing of the new Parisian plan of regulating Cab-fares by distance, which is to be shown by an automatic apparatus, venteth his feelings of dismay and disgust in anticipation of the application of the new-fangled System nearer home.]

A Autumn-attic happaratus

For measuring off our blooming fares!

Oh, hang it all! They slang and slate us;

They say we crawls, and cheats, and swears.

And we surwives the sneering slaters,

Wot tries our games to circumvent,

But treating us like Try-yer-weighters,

Or chockerlate, or stamps, or scent!

Upon my soul the stingy dodgers

Did ought to be shut up. They're wuss

Than Mrs. JACKERMETTY PRODGERS,

Who earned the 'onest Cabman's cuss.

It's sickening! Ah, I tell yer wot, Sir,

Next they'll stick hup—oh, you may smile—

This:—"Drop a shilling in the slot. Sir,

And the Cab goes for just two mile!"

Beastly! I ain't no blessed babby,

Thus to be measured off like tape.

Yah! Make a autumn-attic Cabby,

With clock-work whip and a tin cape.

May as well, while you're on the job, Sir.

And then—may rust upset yer works!

The poor man of his beer they'd rob, Sir,

Who'd rob poor Cabby of his perks!

Oh, mountainous mouther of molehills, weak wielder of terrors outworn,

Discharger of sulphurous salvoes, effetely ferocious in scorn,

Shrill shrieker and sesquipedalian, befoamed and befumed and immense

With the words that are wind on an ocean, whose depth is unfathomed of sense,

Red fury that smitest at shadows, black shadows of blood that is red

In the face of a soulless putrescence, doomed, damned, deflowered and dead;

Oh, robed in the rags of thy raging, like tempests that thunder afar,

In a night that is fashioned of Chaos discerned in the light of a star,

For the verse that is venom and vapour, discrowned and disowned of the free,

Take thou from the shape that is Murder, none other will thank thee, thy fee.

Yea, Freedom is throned on the Mountains; the cry of her children seems vain

When they fall and are ground into dust by the heel of the lords of the plain.

Calm-browed from her crags she beholdeth the strife and the struggle beneath.

And her hand clasps the hilt, but it draws not the sword of her might from its sheath.

And we chide her aloud in our anguish, "Cold mother, and careless of wrong,

How long shall the victims be torn unavenged, unavenging? How long?"

And the laugh of oppressors is scornful, they reck not of ruth as they urge

The hosts that are tireless in torture, the fiends with the chain and the scourge,

But at last—for she knoweth the season—serene she descends from the height,

And the tyrants who flout her grow pale in her sunrise, and pray for the night.

And they tremble and dwindle before her amazed, and, behold, with a breath,

Unhasting, unangered advancing, she dooms them to terror and death.

But she the great mother of heroes, the shield and the sword of the weak,

What lot or what part has her glory in madmen who gibber and shriek?

Her eye is as death to assassins, the brood of miasma and gloom,

Foul shapes that grow sleek upon slaughter, as worms that are hid in a tomb.

In the dawn she has marshalled her armies, the millions go marching as one,

With a tramp that is fearless as joy, and a joy that is bright as the sun.

But the minions of Murder move softly; unseen they have crept from their lair,

In a night that is darker than doom on the famishing face of despair.

And they lurk and they tremble and cower, and stab as they lurk from behind,

Like shapes from a pit Acherontic by hatred and horror made blind.

These are not the soldiers of Freedom; the hearts of her lovers grow faint

When the name of assassin is chanted as one with the name of a saint.

And thou the pale poet of Passion, who art wanton to strike and to kill,

Lest her wrath and her splendour abash thee and scorch thee and crush thee, be still.

It having occurred to me that within a few days I might get an entire change by visiting some thoroughly French seaside places on the coast of Normandy, I started viâ Southampton for Havre.

I started mysteriously at midnight. Lights down. We glided out, almost sneaked out, as if ashamed of ourselves. I had pictured to myself sitting out on deck, enjoying the lovely air and the picturesque view. L'homme propose, la mer dispose. I retired early, and enjoyed neither the lovely air nor the picturesque view. "The rest is—silence," or as much silence as possible, and as much rest as possible.

8'30 A.M.—Le Havre. Consul's chief attendant,—Lictor, I suppose, the master being a consul,—sees me and my baggage through the customs—"customs more honoured in the breach than the observance,"—and in five minutes I am—that is, we are, the pair of us—at the Hôtel Frascati, which, whether it be the best or not I cannot say, is certainly the liveliest, and the only one with a covered terrace facing the sea where you can breakfast, dine, and generally enjoy a life which, for the time being, is worth living. À propos of this terrace, I merely give the proprietor of Frascati a hint,—the one drawback to the comfort of dining or breakfasting in this upper terrace is the door which communicates with the lower terrace, and through which everyone is constantly passing. We know that Il faut qu'une porte soit ouverte ou fermée. But this is opened and shut, or not shut, and, if shut, more or less banged, every three minutes. If it isn't banged, it bursts open of its own accord, and whacks the nearest person violently on the back, or hits a table, and scatters the bottles, or, if not misbehaving itself in this way (which is only when rude Boreas is at his rudest), it admits such a draught as causes bald-headed men to rage, ladies to shiver, delicate persons to sneeze, and, finally, impels the diners to raise such a clattering of knife-handles on the different tables, as if they were applauding a speech or a comic song. Then the maître-d'hôtel rushes at the door and closes it violently,—only for it to be re-opened a minute afterwards by a waiter or visitor entering from the terrace below! A mechanical contrivance and a light screen would do away with the nuisance, for a nuisance it most undoubtedly is. The perpetual banging causes headache, irritation, and indigestion, and those who have suffered n'y reviendront pas, like several Marlbrooks. Let the proprietor look to this, and, where most things are done so well, and not unreasonably, don't let there be a Havre-and-Havre policy of hotel management. Allons!

I am writing this paper for the sake of those who have only a very few days for a holiday, and like to make the most of it in the way of thorough change. If you select Havre as your head-quarters for Trouville, Cabourg, and Dives, you must be a good sailor, as you can only reach these places by sea; and three-quarters of an hour bad passage there, with the prospect of three-quarters of an hour worse passage back at some inconvenient hour of the evening, destroys all chance of enjoyment. If you're not a good sailor, remain on the Havre side of the Seine, and there's plenty to be seen there to occupy you from Saturday afternoon till Wednesday evening, when The Wolf (what a name!) makes its return voyage to Southampton.

If the sea at Dives, in 1066 A.D., had been anything like what it was at Havre the other day, when I wanted to cross over to Dives, WILLIAM THE CONQUEROR would never have sailed from that place for the invasion of England. Dull as he might have found Dives, yet I am sure the Conquering Hero would have preferred returning to Paris, to risking the discomfort of the crossing. By the way, the appropriate station in Paris for Dives would be Saint-Lazaire.

Then there are Honfleur, and Harfleur, and most people know Ste. Adresse and Etretat. The views and the drives are not equal to those about Ilfracombe and Lynton, and Etretat itself is only a rather inferior kind of Lynmouth. Those who want bracing won't select either Ste. Adresse or Etretat or Havre for a prolonged stay. Taking for granted the short-holiday-maker will visit all these places, let me give him a hint for one day's enjoyment, for which, I fancy, I shall earn his eternal gratitude. Order a carriage with two horses at Havre, start at nine or 9'30, and drive to Etretat by way of Marviliers. Stop at the Hôtel de Vieux Plats at Gonneville for breakfast. Never will you have seen a house so full of curiosities of all sorts; the walls are covered with clever sketches and paintings by more or less well-known artists, and the service of the house is carried on by M. and Mme. AUBOURG, their son and daughter, who, with the assistance of a few neat-handed Phyllises, do everything themselves for their customers, and are at once the best of cooks, somméliers, and waiters. So cheery, so full of life and fun, so quick, so attentive, serving you as if you were the only visitor in the place, though the little inn is as full as it can be crammed, and there are fifty persons breakfasting there at the same moment.

Every room being occupied, and every nook in the garden too, we are accommodated with a rustic table in the "Grand Salon," part of which is screened off as a kind of bar. The "Grand Salon" is also full of quaint pictures and eccentric curiosities; it is cool and airy, bright flowers are in the windows, and the floor is sanded. We had stopped here to refresh the horses, intending to breakfast at Etretat. But so delighted were we, a party of "deux couverts," with this good hotel, and still more with the famille Aubourg, that, though we had driven away, and were a mile further on our road to Etretat, we decided—and Counsellor Hunger was our adviser too—on returning to this house where we had noticed breakfast-table tastefully laid out for some expected visitors, and had been in the kitchen, and with our own eyes had seen, and with our own noses had smelt the appetising preparation for the parties already in possession. So we drove back again rapidly, much to the delight of our coachman, who had become very melancholy, and was evidently forming a very poor opinion of persons who could lose the chance of a breakfast chez Aubourg.

How pleased Mlle. AUBOURG, the waitress, appeared to be when we returned! All the family prepared to kill the fatted calf figuratively, as it took the shape of the sweetest and freshest shrimps as hors d'oeuvre, and then it became an omelette au lard ("O La!") absolutely unsurpassable, and a poulet sauté, which was about the best that ever we tasted. A good bottle of the ordinary generous, fruit, and then a cup of recently roasted and freshly ground coffee with a thimbleful of some special Normandy cognac,—in which our cheery host joined us, and we all drank one another's healths,—completed as good a déjeuner as any man or woman of simple tastes could possibly desire.

Then the cheery son of the house, dressed in a cook's cap and apron, pauses in his work to join in our conversation. He tells us how he has been in London, and can speak English, and is enthusiastic about the satiric journal which Mr. Punch publishes weekly. M. AUBOURG fils who is a truthful likeness, on a large scale, of M. DAUBRAY, of the Palais Royal, informs me that he can play the horn after the manner of the guards on the coaches starting from the [pg 89] "White Horse," Piccadilly; and so, when we start for Etretat, he produces a big cor de chasse, and, while he sounds the farewell upon it, a maid rushes out and rings the parting bell, and M. AUBOURG pére waves his cap, and Madame her hand, and Mlle. her serviette, and we respond with hat and handkerchief until we turn the corner, and hear the last flourish of the French "horn of the hunter," and see the last flourish of pretty Mademoiselle's snow-white serviette. Then we go on our way to Etretat, rejoicing. But, after this excitement, Etretat palls upon us. After a couple of hours of Etretat, we are glad to drive up, and up, and up, and get far away and above Etretat, where we can breathe again.

Far better is Fecamp which we tried two days after, and Fecamp is just a trifle livelier than Westward Ho! Of course its Abbaye is an attraction in itself. It is a place whose inhabitants show considerable public spirit, as it is here that "Benedictine" is made. When at Le Havre drive over to St. Jouin, and breakfast chez Ernestine. Another day you can spend at Rouen, returning in the evening to dinner. This is not intended as a chapter in a guidebook, but simply as a hint at any time to those who need a thorough change in a short time, and who do not care to go too far off to get it. When they've quite finished building and paving Havre, I'll return there and take a few walks. Now the authorities responsible for the paving are simply the best friends of the boot-making interest, just as in London the Hansoms collectively ought to receive a handsome Christmas hat-box from the hatters. But mind this, when at Havre drive to Gonneville, and breakfast chez M. AUBOURG.

I have had a communication from Mr. JEREMY, written in the execrable English of which this calico-livered scoundrel is a consummate master, and informing me that, if I care to join the staff of the journal which Mr. J. directs, a princely salary shall be at my disposal. Mr. J. inquires what special branch of fiction it would suit me to undertake, as he proposes to publish a serial novel by an author of undoubted imaginative power. Here is my answer to Mr. J. I will do nothing for him. His compliments I despise. Flattery has never yet caused me to falter. And if he desires to prop the tottering fortunes of his chowder-headed rag, let him obtain support from the pasty-faced pack of cacklers who surround him. I would stretch no finger to help him, no, not if I saw him up to his chin in the oleo-margarine of which his brains and those of his bottle-nosed, flounder-eared friends seem to be composed. So much then for Mr. J. Du reste, as TALLEYRAND once said, my important duties to the readers of this journal fully absorb my time.

Last week I offered to the public some interesting details of the family history of an exalted German prince, whose friendship and good-will it has been my fortune to acquire by means of the dazzling accuracy of my forecasts of racing events in this country. I may state at once that the Grand Cross of the Honigthau Order, "mit Diamanten und Perlen," which his Serene Highness was good enough to confer upon me, has come to hand, and even now sparkles on a breast as incapable of deceit as it is ardent in the pursuit of truth. Let this be an incitement to the deserving, and a warning to scoffers who presume to doubt me. Many other gratifying testimonies of foreign approval have reached me. From the immense heap of them stored in my front drawing-room, I select the following specimens:—

Revolution crushed entirely by your aid. At the crisis, General Pompanilla read all your published writings aloud to insurgent chiefs. Effect was magical. They thought your prophecies better than ammunition. Ha, ha! Their widows have fled the country. A pension of a million pesetas awarded to you. Rumours about my resignation a mere blind.

(Signed) Dr. Celman, President.

The traitor Celman has been vanquished, thanks to you. When ammunition failed, we loaded with sporting prophecies. Very deadly. Treasury cleared directly. One of your adjectives annihilated a brigade of infantry.

(Here follow the signatures of the Leaders of the Union Civica, to the number of 5,000.)

Victorious army of Guatemala sends thanks to its brave champion. Your inspired writings have been set to music, and are sung as national hymns. Effect on San Salvadorians terrible. Only two deaf sergeants left alive. Guerra, Vittoria Matador, Mantilla.

(Signed) BARILLAS, President.

Land pirates from Guatemala foiled, owing to valiant English Punch-Prophet. Army when reduced to last biscuit, fed on racing intelligence. Captain-General sustained nature on white native plant called Tehp, much used by Indian tribe of Estar-ting-prisahs. My body-guard performed prodigies on Thenod, the well-known root of the Cuff plant. Have adopted you as my grandson.

(Signed) Ezeta, President.

That is sufficient for one week. Those who wish for more in the meantime, must call at my residence.

The Commissioner. Sorry to see you here, Sir, as your presence argues that you have a right to demand redress.

Engineer Officer, R.N. I think, Sir, that we have a genuine grievance is almost universally conceded. But, as our labours and responsibilities have increased enormously of late years, perhaps you will kindly allow me to describe our duties.

The Com. By all means.

En. Of., R.N. As the matter is of the greatest importance to fourteen hundred officers, commanding ten thousand men, I hope you will not consider me tedious in making the following statement. The success of every function of the modern battle-ship depends upon machinery for which the Engineer officers are directly responsible. By its means the anchor is lifted, boats are hoisted, the ship is steered, ventilated, and electrically lighted. Pure drinking water is supplied for its hundreds of inhabitants. The efficiency of all the elaborate arrangements of the hull for safety in collision, fire, or battle, depends upon the Engineers. Their machinery trains and elevates, loads and controls the heavy guns. The use of the Whitehead torpedo and all its appliances would be an impossibility without the Engineers. In addition to this there is the propulsion of the ship, and the control and supervision of a large staff of artificers and men. And yet the Engineer officers are the lowest paid class of commissioned officers in the Royal Navy—this when, without exaggeration, they may be described as the hardest-worked.

The Com. It certainly seems unfair that officers of your importance should not receive ampler remuneration. When was the rate established?

En. Of., R.N. It has seen little change since 1870; and you may judge of its justice when I tell you that a young Surgeon of twenty-three, appointed to his first ship, receives more pay than many Engineer officers who have seen fourteen years' service, and have reached the age of thirty-five.

The Com. I am decidedly of opinion that your pay should be increased, and I suppose (as evidently there has been "class feeling" in the matter) you have had to suffer annoyance anent relative rank?

En. Of., R.N. (with a smile). Well, yes, we have. But if the Engineer-in-Chief at the Admiralty (who, by the way, receives £1000 a-year, and yet is held responsible for the design and manufacture of machinery costing £12,000,000 per annum) is admitted to be superior to all other Engineer officers, we shall be satisfied. Still I cannot help saying that the Chief Engineer of a ship is snubbed when all is right, and only has his importance and responsibility allowed (when indeed it is recognised and paraded) when anything is wrong! But let that pass.

The Com. I am afraid it is too late to do anything further this Session, as the House is just up. However, if matters are not more satisfactory at the end of the recess, let me know, and—but you shall see!

[The Witness, after suitable acknowledgment, then withdrew.

"A LITTLE MORE THAN GAY BUT LESS THAN GRAVE."—Not very long ago, an act of sacrilege was committed at Canterbury by a man, who robbed an alms-box in the Cathedral. However, disregarding the precedent set some time since by the Dean and Chapter (who it will be remembered dug up and removed the bones of the honoured dead) the intruder abstained from touching the vaults of those buried in consecrated ground.

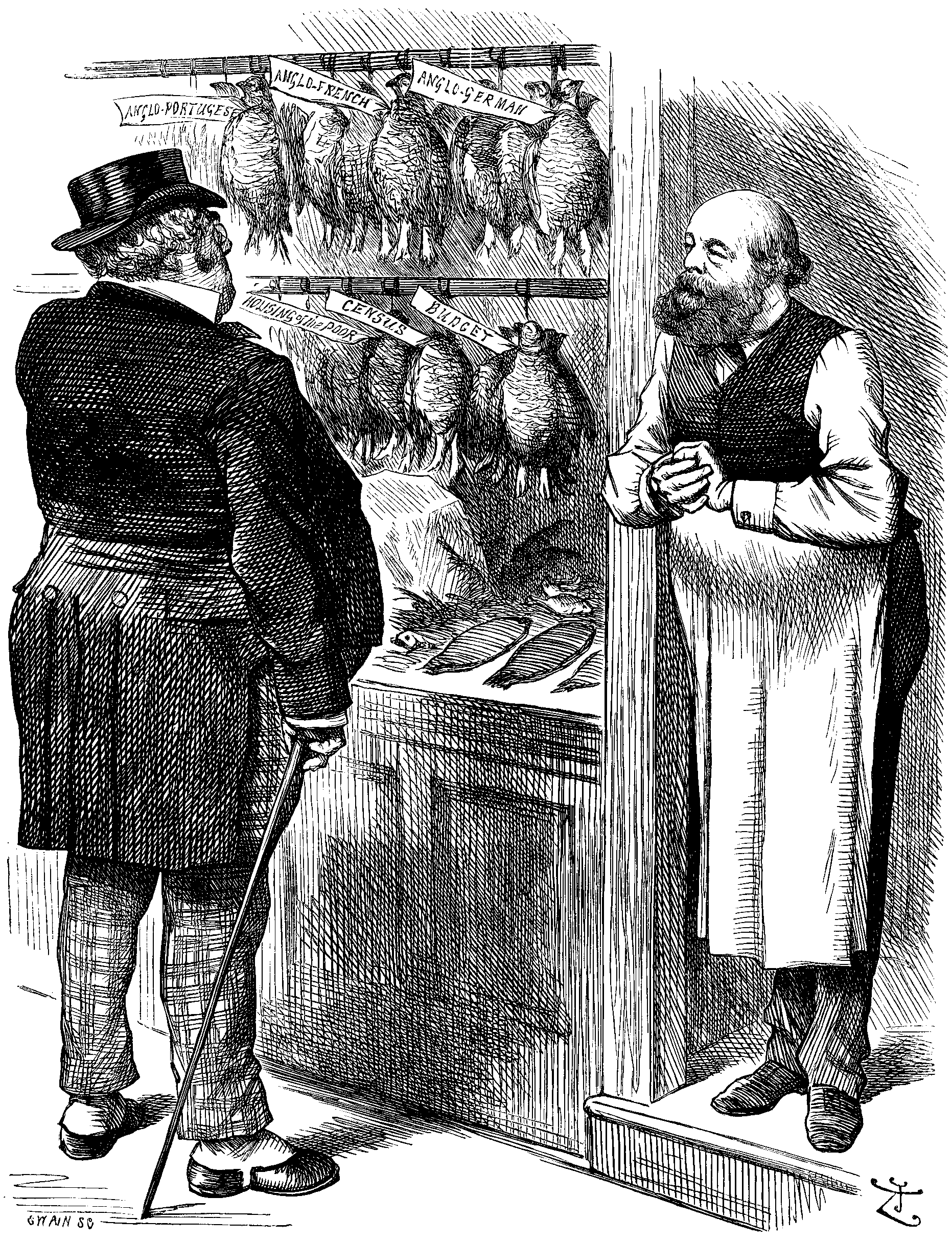

Small game and scant! The Season's show

Of Birds, in bunches big, adjacent,

Will hardly take JOHN's eye, although

The Poulterer appears complacent,

Seeing, good easy man, quite clearly

That rival shops show yet more queerly.

It can't be said the Birds look young,

Or plump of breast, or fine of feather.

A skinnier lot than SOL has hung

Ne'er skimmed the moor or thronged the heather;

But for dull plumage, shrivelled crop,

Look at the Opposition shop!

Amongst the blind the one-eyed king

Is, not unnaturally, bumptious.

That Poulterer with a swaggering swing

Strides to his door, the stock looks "scrumptious"

In his eyes; but thrasonic diction

To BULL will hardly bring conviction.

"Humph!" mutters JOHN. "A poorish lot!

Scarce tempting to the would-be diner;

This year, SOL,—or may I be shot!—

Your foreign birds appear the finer.

The Home moors have not yielded? Well, Sir,

Let's hope your stock, though scant, may sell, Sir!

"Eh? What? Do better later on?

Give a look in about November?

Well, for the time I must be gone,

Off to the Sea! But I'll remember.

My judgment heat or haste shan't fetter,

But, up to now—things might look better!"

Mon cher "CHAP,"—Je connais pas votre surnom et c'est pourquoi je vous appelle "chap,"—vous pouvez comprendre, je crois, que c'est difficile de commencer un correspondence dans une langue qui n'est pas le votre, et surtout avec un chap que vous ne connais pas, mais il faut faire un commencement de quelque sorte, et malgré qu'on m'a dit que vous "fellows," êtes des duffers (expression Anglaise. Un duffer c'est une personne qui n'est pas dans le "swim"), qui ne comprenderaient pas un seul mot que je dirai sur le sujet, jamais le plus petit, j'essayerai a expliquer brefment qu'est-ce que c'est que Le "Cricket."

Eh bien, le cricket est un "stunning" jeu. "Stunning" est une autre expression Anglaise qui veut dire qu'une chose est regulairement "a, un," ou de me servir d'argot, "parfaitement de première côtelette," et qui "prend le gâteau." Pour faire un coté de cricket, il faut onze. Je ne suis pas encore dans notre onze, mais j'espère d'être là un de ces jours. Mais pour continuer. Il y a le "wicket," une chose fait de trois morceaux de bois, a qui le "bowler" jette la balle, dur comme une pierre, et si ça vous attrappe sur le jambe, je vous promis, ça vous fera sauter. Et bien, avant le wicket se place l'homme qui est dedans et qui tient dans ces mains le "bat" avec lequel il frappe la balle et fait des courses. L'autre jour dans un "allumette" entre deux "counties," un professional qui s'appelle Fusil a fait plus que deux cents des courses.

Mais pour continuer encore. Si l'homme qui est dedans ne frappe pas la balle, et la balle au contraire frappe les "wickets," on tourne a un personage qui s'apelle le "Umpire" et lui dit, "Comment ça, Monsieur l'Umpire?" et il dit, "Dehors!" ou, "Pas dehors!"—et quand tous les onze sont "dehors" le innings est fini, et l'autre côté commence. Et voilà le cricket. N'est-ce pas qu'il est, comme j'ai dis, un stunning jeu? Eh bien, je crois que, pour une première lettre, j'ai fait le chose en style. Ecrivez vous maintenant en réponse, et donnez moi une description d'un de votre jeux, pour me montrer que vous Français ne sont pas, comme nous pensons en Angleterre, tous des "duffers." Le votre sincerement, TOMMY.

My excellent comrade,—I have just been in receipt of your epistle, profound, interesting, but antagonistic concerning your JOHN BULL's prizefighting, high life, sportsman's game, your Jeu de Cricquette, about which I will reply to you in my next. Accept the assurance of my most distinguished consideration, JULES.

A DANGEROUS CORNER.—A ring in Chemicals is proposed, which, if formed, will cost the public about ten millions sterling. Whether the said public will see any return for its money is problematical. However, it may be hinted that the end of Chemicals is frequently smoke, and sometimes an explosion which blows up the company!

"We beseech your MAJESTY to accept our assurances of the contentment of your MAJESTY's Canadian subjects with the political connection between Canada and the rest of the British Empire, and of their fixed resolve to aid in maintaining the same."—Loyal Address to the Queen from Canada.

Accept them? Punch believes you, boys,

And store them 'midst our choicest treasures!

In these fierce days of factious noise

The Sage experiences few pleasures

So genuine as this outburst frank

Of "true Canadian opinion."

He hastens heartily to thank

The loyal hearts of the Dominion!

Mother and daughter should be tied

By trustful faith and free affection.

If ours be mutual love and pride,

Who's going to "sever the connection"?

Let plotters scheme, and pedants prate,

They will not pick our true love's true lock

Whilst truth and justice arm the State

With friends like AMYOT and MULOCH!

Mother and daughter! Love-linked like

Persephone and fond Demeter.

Fleet to advance, and strong to strike,

And yearly growing stronger, fleeter,

Miss CANADA need not depend

On Dame BRITANNIA altogether,

But she may trust her as a friend,

Faithful in fair or threatening weather.

Tour hand, Miss, with your heart in it,

You to the Mother Country proffer.

Beshrew the cynic would-be wit.

Who coldly chuckles at the offer!

BRITANNIA takes it, with a grip

That on the sword, at need, can clench too, too!

She will not that warm grasp let slip,

Health, boys of British blood,—and French

DEAR MR. PUNCH,—Cannot you do something to help us, and save us from a permanent consignment to that wretched hole-in-a-corner back street site thrust upon us at the rear of the National Gallery? We do not know how far matters may have gone, but somebody wrote the other day to The Times to protest against the job, and we conclude, therefore, it may not yet, perhaps, be too late to agitate for a stay of execution. We are not difficult to please, and would be contented with a modest but suitable home in any convenient locality. That such can be found when really sought for, witness the happy facility with which a fitting residence has been discovered in the east and west galleries surrounding the Imperial Institute for the promised new National Collection. At South Kensington we had a narrow escape of a conflagration, from too close a proximity to the kitchen of a shilling restaurant. At Bethnal Green we have been having a prolonged merry time of it, with damp walls behind us and leaking roofs above our heads. At one time we were packed away in dusty obscurity, in the cupboards of a temporary Government office; and looking back on the past, fruitful as it is in recollections of official slights and snubs, you may gather that we can have no very ambitious designs for the future. We do, however, protest against being tacked on as a sort of outside back-stair appendage to the National Gallery, that will soon want the space we shall be forced to occupy for its own natural and legitimate expansion. Suggest a site for us—anywhere else. There is still room on the Embankment. Kensington Palace—is still in the market. Why not be welcome there? As representatives for all of us, I subscribe my name hereunder, and remain,

Your obedient servant,

JOSHUA REYNOLDS (late P.R.A.)

| 1. The first thing is to teach the Colt to Lead. | 2. Next put on the Bridle, and drive him quietly. |

| 3. After this you may get on his Back. | 4. Ride him gently at first, and avoid using the Whip. |

| 5. Make the Pupil understand, firmly but quietly, that you are his Master. | 6. Then, after a few Lessons, you will have broken the Colt (or he will have broken you). |

The Season's over; for relief

You're off to scale the Alps;

Say, do you, like some Indian Chief,

Look back and count your scalps?

Does someone rue your broken vows,

And sigh he has to doubt you;

Yet felt withal the week at Cowes

Was quite a blank without you?

Are hearts still broken, as of old,

In this prosaic time,

When love is only given for gold,

And poverty's a crime.

Say, are you conscious of a heart,

And can you feel it beating;

And is it ever sad to part,

And finds a joy in meeting?

The Seasons come, the Seasons go,

With store of good and ill;

Do all men find you cold as snow,

And unresponsive still?

O beautiful enigma, say,

Will love's sublime persistence

Solve for you, in the usual way,

The riddle of existence?

Alas! love is not love to-day,

But just a bargain made,

In cold and calculating way;

And if the price be paid,

A man may win the fairest face,

A maiden tall and queenly,

The daughter of some ancient race,

Who sells herself serenely.

What wonder that the cynic sneers

At such a rule of life;

That, after but a few short years,

Dissension should be rife.

Ah! Lady, you'll avoid heart-ache,

And scorn of bard satiric,

If haply you should deign to take

A lesson from our lyric.

"Lead, kindly Light!" From lips serene as strong,

Chaste as melodious, on world-weary ears

Fall, 'midst earth's chaos wild of hopes and fears,

The accents calm of spiritual song,

Striking across the tumult of the throng

Like the still line of lustre, soft, severe,

From the high-riding, ocean-swaying sphere,

Athwart the wandering wilderness of waves.

Is there not human soul-light which so laves

Earth's lesser spirits with its chastening beam,

That passion's bale-fire and the lurid gleam

Of sordid selfishness know strange eclipse?

Such purging lustre his, whose eloquent lips

Lie silent now. Great soul, great Englishman!

Whom narrowing bounds of creed, or caste, or clan,

Exclude not from world-praise and all men's love.

Fine spirit, which the strain of ardent strife

Warped not from its firm poise, or made to move

From the pure pathways of the Saintly Life!

NEWMAN, farewell! Myriads whose spirits spurn

The limitations thou didst love so well,

Who never knew the shades of Oriel,

Or felt their quickened spirits pulse and burn

Beneath that eye's regard, that voice's spell,—

Myriads, world-scattered and creed-sundered, turn

In thought to that hushed chamber's chastened gloom.

In all great hearts there is abundant room

For memories of greatness, and high pride

In what sects cannot kill nor seas divide.

The Light hath led thee, on through honoured days

And lengthened, through wild gusts of blame and praise,

Through doubt, and severing change, and poignant pain,

Warfare that strains the breast and racks the brain,

At last to haven! Now no English heart

Will willingly forego unfeigned part

In honouring thee, true master of our tongue,

On whose word, writ or spoken, ever hung

All English ears which knew that tongue's best charm.

Not as great Cardinal such hearts most warm

To one above all office and all state,

Serenely wise, magnanimously great;

Not as the pride of Oriel, or the star

Of this host or of that in creed's hot war,

But as the noble spirit, stately, sweet,

Ardent for good without fanatic heat,

Gentle of soul, though greatly militant,

Saintly, yet with no touch of cloistral cant;

Him England honours, and so bends to-day

In reverent grief o'er NEWMAN's glorious clay.

"In a recent case of brigandage, people of all sorts and classes were implicated, while one of the leading barristers was imprisoned on suspicion."—Report of Consul Stigano, of Palermo.

SCENE—Chambers of Mr. E.S. TOPPEL, Q.C., in the Inner Temple. Mr. TOPPEL discovered in consultation with a Chancery Barrister, two Starving Juniors, and sixteen Masked Ruffians armed to the teeth.

Mr. Toppel. Now that we have the Lord Chancellor, the Lord Chief Justice, and the President of the Divorce Division, securely locked up together in the attic, and gagged, we may, I think, congratulate ourselves on the success of our proceedings so far! We are, I am sure, quite agreed as to there having been no other course open to us than to imitate our Sicilian brethren of the robe, and take to a little mild brigandage, considering the awful decay of legal business and our own destitute condition. (Sympathetic cries of Hear, hear! from the Chancery Barrister, and the two Starving Juniors.) I have no doubt that a few hours spent in our attic will induce the High Legal Dignitaries I have mentioned (laughter) to pay up the modest ransom we demand, and to take the additional pledge of secresy. Meanwhile, I propose that these sixteen excellent gentlemen should re-enter the private Pirate Bus' which is waiting down-stairs, and see whether the Master of the Rolls could not be—er—"detained in transitu" (more laughter) while proceeding to his Court. It would be best, perhaps, as Lord ESHER belongs to the Equity side, for our friend here of the Chancery Bar to accommodate him in his Chambers.

Chancery Barrister (alarmed). But I have only a basement!

Mr. Toppel (calmly). A basement will do very well. (To the sixteen Masked Men). You will probably find Lord ESHER somewhere about Chancery Lane. Impress on him that our fee in his case is a thousand guineas; or—both ears lopped off! [Exeunt the Sixteen.

First Junior. I went upstairs just now, in order to see how our distinguished prisoners were getting on. The CHANCELLOR, I regret to say, seemed dissatisfied with the bread and water supplied to him, and asked for "necessaries suitable to his status." He appeared inclined to argue the point; so I had to gag him again.

Mr. Toppel. Quite right. You might have told him that he is now governed by the lex loci, and that we shall reluctantly have to send little pieces of him to his friends—I believe that is the "common form" in brigand circles—if he persists in refusing the ransom. How does the LORD CHIEF JUSTICE bear it?

Second Junior. Not well. The attic window is, fortunately, barred, but I found him trying to—in fact, to disbar it—(laughter)—and to attract the attention of a passer-by. He is now secured by a chain to a strong staple.

Mr. Toppel. I suppose he is not disposed to make the assignment to us of half his yearly salary, which we suggested?

Second Junior. Not yet. He even threatens, when liberated, to bring our conduct under the notice of the Benchers.

Mr. Toppel (grimly). Then he must never be liberated! It's no good beginning this method of what I may call, in technical language, 'seisin,' unless we go the whole hog. Well, if you two Juniors will attend to our—em—clients upstairs—(laughter)—I and our Chancery friend will superintend the temporary removal of Lord ESHER from the Court that he so much adorns. (Noise heard.) Ah, that sounds like Sir JAMES HANNEN banging on the ceiling! He must be stopped, as it would be so very awkward if a Solicitor were to call. Not that there's much chance of that nowadays. (To Chancery Barrister.) Come—shall we try a "set-off"? [Exeunt. Curtain.

"That (the defeat of our measures) was all due to Obstruction.... It appears that Crown and Parliament are alike to be disestablished, and that in their stead we are to put the Obstructive and the Bore.... I should like to ask them what kind of Government they think best, a Bureaucracy or a Bore-ocracy?"—Mr. Balfour at Manchester.

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary,

Over many a dry and dusty volume of Blue-Bookish lore,—

While I nodded nearly napping, suddenly there came a yapping,

As of some toy-terrier snapping, snapping at my study door.

"'Tis some peevish cur," I muttered, "yapping at my study door,—

Only that,—but it's a bore."

Ah! distinctly I remember, it was drawing nigh September,

And each trivial Tory Member pined for stubble, copse, and moor;

Eagerly they wished the morrow; vainly they had sought to borrow

From their SMITH surcease of sorrow, or from GOSCHEN or BALFOUR,

From the lank and languid "miss" the Tory claque dubbed "Brave BALFOUR,"

Fameless else for evermore.

Party prospects dark, uncertain, sombre as night's sable curtain,

Filled them, thrilled them with fantastic funkings seldom felt before;

So that now, to still the beating of faint hearts, they kept repeating

Futile formulas, entreating Closure for the "Obstructive Bore"—

With a view to Truth defeating, such they dubbed "Obstructive Bore,"

As sought Truth, and nothing more.

Presently my wrath waxed stronger; hesitating then no longer,

"Cur!" I said; "mad mongrel, truly off your precious hide, I'll score;

Like your cheek to come here yapping, just as I was gently napping;

You deserve a strapping,—yapping, snapping at my study door.

I shall go for you, mad mongrel!" Here I opened wide the door.

Darkness there, and nothing more!

Deep into that darkness peering, long I stood there nothing hearing,

Doubting, dreaming dreams of Spooks, Mahatmas, Esoteric lore;

But the silence was unbroken, and the stillness gave no token.

Hist! there were two words soft spoken, those stale words, "Obstructive Bore."

Bosh! I murmured, and some echo whispered back, "Obstructive Bore":

Merely that, and nothing more.

Back into my study turning, with some natural anger burning,

Soon again I heard a sound more like miauling than before.

"Surely," said I, "surely that is a grimalkin at my lattice.

Let me see if it stray cat is, and this mystery explore;

Where's that stick? Ah! wait a moment: I'll this mystery explore;

It shall worry me no more!"

Open here I flung the shutter, when, with many a smirk and flutter,

In there popped a perky Jackdaw, yapping, miauling as before

(Queer mimetic noises made he), for no introduction stayed he,

But, with plumage sleek, yet shady, perched above my study door,—

Perched upon a bust of GLADSTONE placed above my study door,—

Perched, and croaked "Obstructive Bore!"

Then this mocking bird beguiling my tried temper into smiling

By the lank lopsided languor of the countenance it wore.

"Though you look storm-tost, unshaven, you," I said, "have found a haven,

Daw as roupy as a raven! Was it you yapped at my door?

Tell me your confounded name, O bird in beak so like BALFOUR!"

Quoth the bird, "Obstructive Bore!"

Much I wondered this ungainly fowl to hear speak up so plainly,

Though his answer little meaning, little relevancy bore;

For we cannot help agreeing that no sober human being

Ever yet was blessed by seeing bird above his study door—

Bird or beast upon the Grand Old bust above his study door,

With the name, "Obstructive Bore."

But the Jackdaw, sitting lonely on that placid bust, spake only

That one word, as though in that his policy he did outpour.

Not another sound he uttered, but his feathers proudly fluttered.

"Ah!" I mused, "the words he muttered other dolts have mouthed before.

Who is he who thinks to scare me with stale cant oft mouthed before?"

Quoth the bird, "Obstructive Bore!"

Startled at the silence broken by reply so patly spoken,

Doubtless, mused I, what it utters is its only verbal store,

Learnt from some unlucky master, whom well-merited disaster

Followed fast and followed faster, till his speech one burden bore—

Till his dirges of despair one melancholy burden bore,

Parrot-like, "Obstructive Bore!"

But the Jackdaw still beguiling my soothed fancy into smiling.

Straight I wheeled my easy-chair in front of bird, and bust, and door;

Then, upon the cushion sinking, I betook myself to linking

Memory unto memory, thinking what this slave of parrot-lore—

What this lank, ungainly, yet complacent thrall of parrot-lore

Meant by its "Obstructive Bore."

This I sat engaged in guessing, strange similitude confessing,

'Twixt this fowl, whose goggle-eyes glared on me from above my door,

And a chap with long legs twining, whom I'd often seen reclining

On the Treasury Bench's lining, Irish anguish gloating o'er;

This same chap with long legs twining Irish anguish chuckling o'er,

Tories christened, "Brave BALFOUR."

Then methought the air grew denser. I remembered stout Earl SPENCER,

And the silly pseudo-Seraph who "obstructed" him of yore;

I remembered Maamtrasma, faction, partisan miasma,

CHURCHILL—CHURCHILL and his henchman, lank and languorous BALFOUR.

"What," I cried, "was ARTHUR, then, or RANDOLPH, in those days of yore?"

Quoth the bird, "Obstructive Bore."

"Prophet!" said I, "of things evil, prophet callous, cold, uncivil,

By your favourite 'Tu quoque' how can you expect to score?

Though your cheek may be undaunted, little memory is wanted,

And your conscience must be haunted by bad memories of yore,

When you were—ah! well, what were you? Tell me frankly, I implore!"

Quoth the bird, "Obstructive Bore."

"Prophet," said I, "of all evil! that we're going to the devil

All along of that 'Obstruction'—which of old you did adore.

Ere you won official Aidenn—is the charge with which is laden

Every cackling speech you make—if you do represent BALFOUR,

That mature and minxish 'maiden' whom the PATS call 'Miss BALFOUR,'"—

Quoth the bird, "Obstructive Bore!"

"Here! 'tis time you were departing, bird or not," I cried, upstarting;

"Get you back unto the Carlton, they on parrot-cries set store.

Leave no feather as a token of the lies that you have spoken

Of the Man, Grand, Old, Unbroken! Quit his bust above my door.

Take thy claws from off his crown, and take thy beak from off my door!"

Quoth the bird, "Obstructive Bore!"

And the Jackdaw, fowl provoking, still is croaking, still is croaking,

On the pallid bust of GLADSTONE just above my study door,

And his eyes have all the seeming of a small attorney scheming;

And the lamp-light o'er him streaming throws his shadow on the floor;

And the shape cut by that shadow which lies floating on the floor,

Looks (to me) OBSTRUCTIVE BORE!

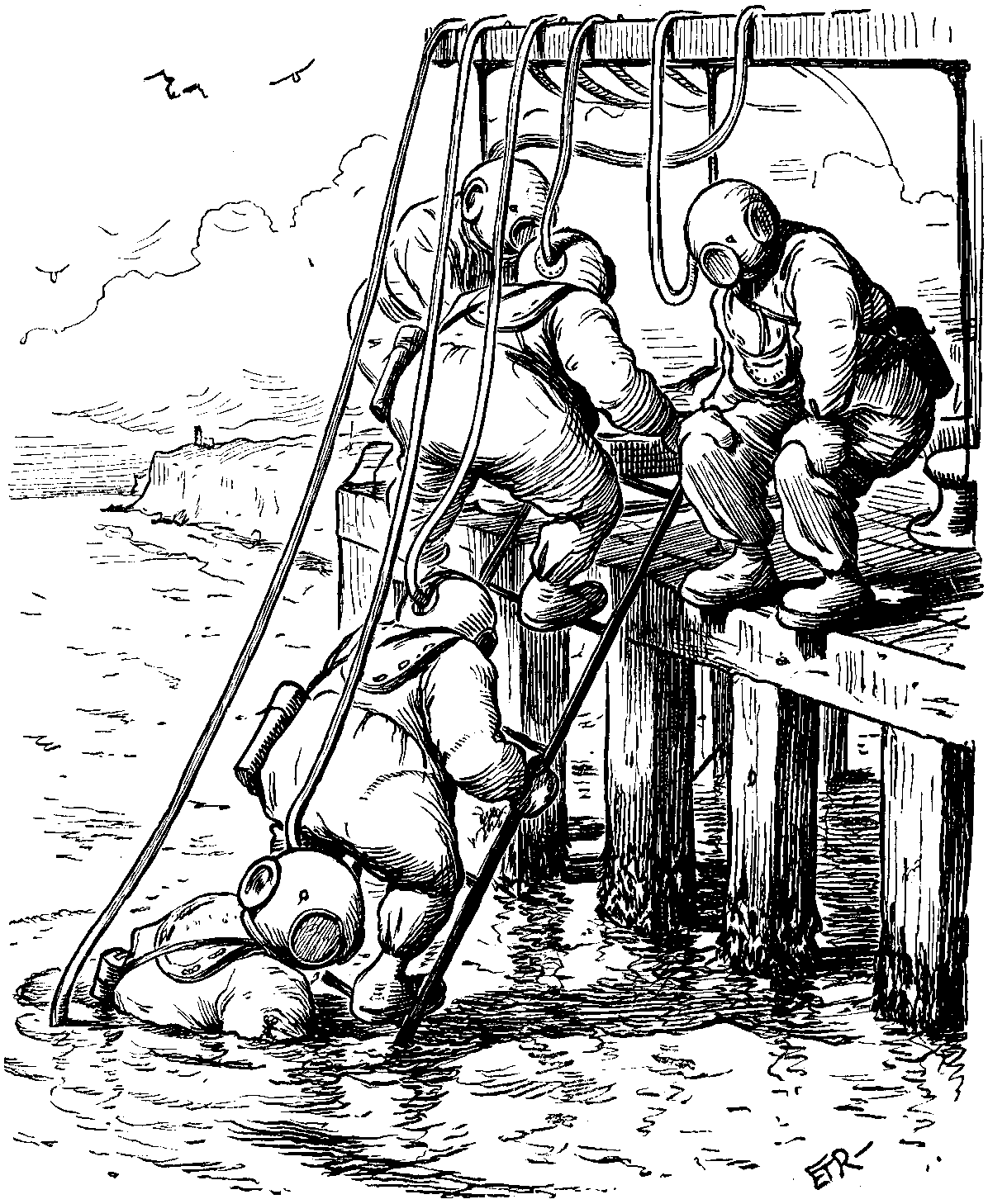

SUBMARINE ENTERPRISE.—It is a pity, perhaps, that on the very first occasion which enabled you to submit, for an experimental trial, to the Dockyard Authorities at Portsmouth, your newly-designed Self-sinking and Propelling Submarine Electric Gun Brig, your vessel, owing, as you say, "to some trifling, though quite unforeseen, hitch in the machinery," should have immediately turned over on its side, upsetting a quantity of red-hot coal from the stoke-hole, and projecting a stifling rush of steam among the four foreign captains, and the two scientific experts whom you had induced to accompany you in your projected descent under the bottoms of the three first-class ironclads at present moored in the harbour. Your alternative ideas of either cutting your vessel in half, and turning it into a couple of diving-bells for the purpose of seeking for hidden treasure on the Goodwin Sands, or of running it under water, for the benefit of those travellers who wish to avoid all chances of sea-sickness, between Folkestone and Boulogne, seem both worthy of consideration. On the whole, however, we should be inclined to think that your last suggestion—namely, that you should put yourself in communication with some highly respectable marine-store dealer, with a view to the disposal of your "Electric Submarine Gun Brig," for the price of old iron, would, perhaps, prove the soundest of all. Still, don't be disheartened.

NOTICE.—Rejected Communications or Contributions, whether MS., Printed Matter, Drawings, or Pictures of any description, will in no case be returned, not even when accompanied by a Stamped and Addressed Envelope, Cover, or Wrapper. To this rule there will be no exception.