"WHAT'S THAT THING YOU'VE GOT ON, ALBERT?"

"TRENCH COAT."

"BUT YOU'VE NEVER BEEN IN THE TRENCHES."

"I KNOW. THAT'S THE IDEA."

No enthusiasm attended the recent revival of the curious May Day custom of dancing round the snow man.

Since the Muzzling Order, says a weekly paper, fewer postmen in the West End have been bitten by dogs. We are asked by the Dogs' Trade Union to point out that this is not due to the Muzzling Order, but to the fact that just at present there is a fine supply of dairy-fed milkmen in that district.

A negress has just died in South America, aged 136. It is supposed that the exodus of so many of her descendants to London on account of the great demand for Jazz-band players was largely responsible for hastening her end.

According to a local paper an American officer refused to stay at a seaside hotel during Easter-time because a flea hopped on to the visitors' book whilst he was in the act of signing it. We agree that it is certainly rather alarming when these unwelcome intruders adopt such methods of espionage in order to discover which room one is about to occupy.

The Society of Public Analysts declares that it is impossible to tell what animal or what part of it is contained in a sausage. We gather that it all depends on whether the beast is backed into the machine or enticed into it with a sardine.

The British people still feel themselves the victors, so Mr. RAMSAY MACDONALD told the Vossische Zeitung. Not Mr. MACDONALD'S fault, of course.

London butchers have protested against being compelled to sell Chilian, Brazilian, Manchurian and other beef. A simple way to distinguish "other beef" from Manchurian beef is to offer it to the cat. If it eats it, it is neither.

The Board of Agriculture claims that since 1914 eleven thousand persons have been taught to make cheese. It is admitted, however, that as the result of inexperience the mortality among young cheeses has been enormous.

The Labour Party are submitting a Motion in the House of Commons for the reduction of railway fares. An alternative suggestion that passengers should be allowed to pay the extra shilling or two and buy the train outright will probably be put forward.

The sum of £15,650 has just been paid for the lease of a West End flat, says a contemporary. If this includes use of the bath, it seems a bit of a bargain.

We gather from an American newspaper that shooting for the new Mexican Presidency has commenced.

An East End fishmonger is reported to have sold fish at one penny a pound. The controlled price being much higher, several trade rivals have offered to bear the expense of a doctor for this man as they feel that something may be pressing on his brain.

A Berlin message indicates that the man who shot KURT EISNER has again been assassinated by the Spartacists. This, of course, cannot be the end of the business. The last and positively final execution of the man still rests with the German Government.

There has never been a case of rabies in Scotland, says The Evening News. This speaks well for the bagpipes as a defensive weapon.

According to a Boston message some Americans gave Admiral WOOD, U.S. Navy, a very cool reception the other day. In shaking hands with him they only broke seven small bones.

We are pleased to be able to say that the recently demobilised soldier who accidentally swallowed some "plum and apple" in a London restaurant is well on the road to recovery.

The number of hot-cross-bun specialists who, since Easter, have been in receipt of unemployment pay has not yet been disclosed for publication.

A dog has returned to its home at Walsworth after being absent for two months. It is feared that he has been leading a double life.

"Throughout the country," says a well-known daily paper, "the hedges and trees are now budding forth into green leaves." This, we understand, is according to precedent.

"Is your rent raised?" asks a contemporary. With difficulty, if he must know.

Newcastle Justices have extinguished eight licences for redundancy. There is no reason for supposing that the offence was intentional.

The report that the prehistoric flint axe recently found at Ascot had been claimed by Sir FREDERICK BANBURY, M.P., is denied. Sir FREDERICK, it appears, merely expressed warm approval of it.

The Manchester Parks Committee is considering the question of opening the Municipal Golf Links for Sunday play. It is contended that the more anti-Sabbatarian features of the game could be eliminated by allowing players to pick out of a bunker without penalty.

Much advice has recently appeared in the Press regarding the treatment of bites received from mad dogs, and in consequence there is a movement on foot among Missionaries to obtain some information regarding the best method of treating the bite of a cannibal.

A Chicago woman has been charged with attempting to shoot her husband with a jewelled and gold-handled revolver. We are pleased to note that the American authorities are determined to put down such ostentation.

It has come to our ears that a certain Conscientious Objector now feels so ashamed of his refusal to fight that he has practically decided to take boxing lessons by post.

"WHAT'S THAT THING YOU'VE GOT ON, ALBERT?"

"TRENCH COAT."

"BUT YOU'VE NEVER BEEN IN THE TRENCHES."

"I KNOW. THAT'S THE IDEA."

(No answers required, thank you.)

To Count Brockdorff-Rantzau, Head of the German Peace Delegation.

The enthralling volume, entitled Preliminary Terms of Peace, on which your attention is being engrossed at the present moment, is said to be of the same length as A Tale of Two Cities. In other respects there is little resemblance traceable between the two works. A more striking likeness is to be found between the present volume and a document produced (also in the neighbourhood of Paris) by the late Prince BISMARCK in 1871. On your return home, if the fancy appeals to you, you might, out of these two publications, construct a very readable romance and call it Two Tales of One City. I think this would be a better name for it than Vice-Versailles.

To Signor Orlando.

Apart from our love for Italy we are, of course, naturally prejudiced in favour of a man who got his surname from one of our own SHAKSPEARE'S heroes, and has consequently given us several easy chances of making little As-you-like-it jokes for the Press in our simple unsophisticated way. All the same I think you were wrong in dropping out of the Big Four like that. If every other Allied delegate were to go off home whenever he couldn't get his own way, or whenever he differed from President WILSON, there might be nobody left to meet the German representatives or to sign any sort of Peace terms. The enemy might even start a Big Four of their own and begin to talk. What should we do then? We might have to send for Marshal FOCH. I'm not sure that in any case this wouldn't be the best plan.

But perhaps you will be back in Paris before this letter reaches you. All roads lead to Rome, and there must be at least one that leads out of it again.

To Ferdinand, Fox.

If news of the outside world ever reaches you in your earth, and you read the discussions on the question whether your old friend WILLIAM ought to be hanged, it can hardly have escaped Your Nosiness that nothing is said about your own claim to similar treatment. Those who never rightly appreciated you may imagine that you will meekly consent to forgo that claim. But, if I know anything of your proud and princely nature, you are, on the other hand, bitterly chagrined at the thought that you have been forgotten so soon.

To a British "Sportsman."

I have often seen you of an afternoon in war-time hanging about in groups along my workaday street, poring over what you regarded as the vital news of the day. It was not a report of any battle in which your brothers were fighting, and, if I had asked you breathlessly, "Who won?" you would not have said, "The British"; you would have said, "SOLLY JOEL'S colt." You had never seen the horse, but you had half-a-dollar of your War-bonus on him, or more probably on one of those who also ran. To-day there are no silly battles to take up good space in your evening print; and, better still, there is no day without its racing matter; no more curtailing of the King of Sports to the lamentable detriment of our national horse-breeding, a subject so close to your heart. The War is indeed well over.

And nothing can be more gratifying to you than to note the rapid progress of Reconstruction in the domain of the Turf. In other spheres of activity there may be a million people drawing the unemployment donation; but here there is immediate occupation for all. The New Jerusalem has been built in a day.

To Peace.

You must not mind if, when you come at last, we treat you like an anti-climax. You see, we let ourselves go, once for all, over the Armistice, and, though there will be plenty of celebrations for you, we shan't forget ourselves again. There will be bands, of course, and bunting, and we shall read the directions in the papers, and buy expensive tickets and get to our seats early. But we shall be respectable and inarticulate this time, like the present exhibition at the Royal Academy. Besides, we have no nice things to shout when the pageants go by, like "Vive la Victoire!" or "Viva la Pace!" and even if we had we should all wait for somebody else to start shouting them.

But you are not to be disappointed; we shall really be glad to welcome you, though we do it in that strange way we have of taking everything as it comes.

I suppose you are bound to assist at your own celebrations, otherwise I should recommend you to be content to read about them next day—about the thundering cheers, the wild enthusiasm that swept like a flame through the vast multitudes, and how "the red glare on Skiddaw roused the Canon (RAWNSLEY) of Carlisle."

To a Multi-Millionaire.

It must be a great satisfaction to you to see how highly the CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER appreciates the loss which the country will sustain by your eventual decease; and that he has proposed to increase materially the amount to be raised out of your estate as a national souvenir of your commercial activities. Indeed you may reflect that, splendid and profitable as your life has been, nothing in it will have become you so much as the leaving of it. With such a thought in your mind the prospect of death should be robbed of a large proportion of its sting.

To a New Knight (Scots).

Out of the eight hundred million pounds' worth of Government material left over from the War, of which two hundred million pounds' worth is expected to be realised in the current year, you should have no difficulty in securing a pair of knightly spurs at quite a reasonable price. They ought to go well with a kilt.

To the Chairman of the "Société des Bains de Mer de Monaco."

Few people can have been better pleased than you at the cessation of hostilities. During all those terrible years the falling-off among the patrons of your world-famous bathing-establishment must have been a source of cruel grief to you. And now there are already myriads who have washed away the stains of war in the pellucid waves that lap your coast of azure.

Here, too, at your hospitable Board of Green Cloth there is forgetfulness of Armageddon save when the cry of "Zéro" recalls to the convalescent British warrior the fateful hour for going over the top.

And to think of Monte Carlo without the guttural Hun and his raucous "Dass ist mein" as he swoops upon his disputed spoils! An Eden with the worm away!

À bientôt!

"PUBLIC SCHOOLS' HIGH JUMP CHALLENGE CUP.—E.C. Archer (Merchant Taylors'), 5 ft. 4 in. (unfinished), 1."—The Times.

We are glad to have later advices which state that he has returned to earth safely.

"Alabaster Lady's Evening Cigarette Case, lid and hinges set with diamonds; left in taxi."—Advt. in "The Times."

We trust the alabaster lady has by now regained her property and with it her marmoreal calm.

I am become an Authority on Birds. It happened in this way.

The other day we heard the Cuckoo in Hampshire. (The next morning the papers announced that the Cuckoo had been heard in Devonshire—possibly a different one, but in no way superior to ours except in the matter of its Press agent.) Well, everybody in the house said, "Did you hear the Cuckoo?" to everybody else, until I began to get rather tired of it; and, having told everybody several times that I had heard it, I tried to make the conversation more interesting. So, after my tenth "Yes," I added quite casually:—

"But I haven't heard the Tufted Pipit yet. It's funny why it should be so late this year."

"Is that the same as the Tree Pipit?" said my hostess, who seemed to know more about birds than I had hoped.

"Oh, no," I said confidently.

"What's the difference exactly?"

"Well, one is tufted," I said, doing my best, "and the other—er—climbs trees."

"Oh, I see."

"And of course the eggs are more speckled," I added, gradually acquiring confidence.

"I often wish I knew more about birds," she said regretfully. "You must tell us something about them now we've got you here."

And all this because of one miserable Cuckoo!

"By all means," I said, wondering how long it would take to get a book about birds down from London.

However, it was easier than I thought. We had tea in the garden that afternoon, and a bird of some kind struck up in the plane-tree.

"There, now," said my hostess, "what's that?"

I listened with my head on one side. The bird said it again.

"That's the Lesser Bunting," I said hopefully.

"The Lesser Bunting," said an earnest-looking girl; "I shall always remember that."

I hoped she wouldn't, but I could hardly say so. Fortunately the bird lesser-bunted again, and I seized the opportunity of playing for safety.

"Or is it the Sardinian White-throat?" I wondered. "They have very much the same note during the breeding season. But of course the eggs are more speckled," I added casually.

And so on for the rest of the evening. You see how easy it is.

However the next afternoon a most unfortunate occurrence occurred. A real Bird Authority came to tea. As soon as the information leaked out I sent up a hasty prayer for bird-silence until we had got him safely out of the place; but it was not granted. Our feathered songster in the plane-tree broke into his little piece.

"There," said my hostess—"there's that bird again." She turned to me. "What did you say it was?"

I hoped that the Authority would speak first, and that the others would then accept my assurance that they had misunderstood me the day before; but he was entangled at that moment in a watercress sandwich, the loose ends of which were still waiting to be tucked away.

I looked anxiously at the girl who had promised to remember, in case she wanted to say something, but she also was silent. Everybody was silent except that miserable bird.

Well, I had to have another go at it. "Blackman's Warbler," I said firmly.

"Oh, yes," said my hostess.

"Blackman's Warbler; I shall always remember that," lied the earnest-looking girl.

The Authority, who was free by this time, looked at me indignantly.

"Nonsense," he said; "it's the Chiff-chaff."

Everybody else looked at me reproachfully. I was about to say that "Blackman's [pg 357] Warbler" was the local name for the Chiff-chaff in our part of Flint, when the Authority spoke again.

"The Chiff-chaff," he said to our hostess with an insufferable air of knowledge.

I wasn't going to stand that.

"So I thought when I heard it first," I said, giving him a gentle smile.

It was now the Authority's turn to get the reproachful looks.

"Are they very much alike?" my hostess asked me, much impressed.

"Very much. Blackman's Warbler is often mistaken for the Chiff-chaff, even by so-called experts"—and I turned to the Authority and added, "Have another sandwich, won't you?"—"and particularly so, of course, during the breeding season. It is true that the eggs are more speckled, but—"

"Bless my soul," said the Authority, but it was easy to see that he was shaken, "I should think I know a Chiff-chaff when I hear one."

"Ah, but do you know a Blackman's Warbler? One doesn't often hear them in this country. Now in Switzerland—"

The bird said "Chiff-chaff" again with an almost indecent plainness of speech.

"There you are!" I said triumphantly. "Listen," and I held up a finger. "You notice the difference? Obviously a Blackman's Warbler."

Everybody looked at the Authority. He was wondering how long it would take to get a book about birds down from London, and deciding that it couldn't be done that afternoon. Meanwhile "Blackman's Warbler" sounded too much like the name of something to be repudiated. For all he had caught of our mumbled introduction I might have been Blackman myself.

"Possibly you're right," he said reluctantly.

Another bird said "Chiff-chaff" from another tree, and I thought it wise to be generous. "There," I said, "now that was a Chiff-chaff."

The earnest-looking girl remarked (silly creature) that it sounded just like the other one, but nobody took any notice of her. They were all busy admiring me.

Of course I mustn't meet the Authority again, because you may be pretty sure that when he got back to his books he looked up Blackman's Warbler and found that there was no such animal. But if you mix in the right society and only see the wrong people once it is really quite easy to be an authority on birds—or, I imagine, on anything else.

The Woman. "JAZZ STOCKINGS ARE THE LATEST THING, DEAR. HERE'S A PICTURE OF A GIRL WITH THEM ON."

The Man. "WHAT APPALLING ROT! ER—AFTER YOU WITH THE PAPER."

(By a Cynic.)

A Dukedom, Grand or otherwise,

No longer is an envied prize

When every day some fierce Commission

Clamours for ducal inhibition.

The style of Marquess—thuswise spelt—

Is picturesque, but, like the belt

Of Earldom, cannot long abide

Or stem the democratic tide.

Viscounties stand to cheer and bless

The labours of the purple Press,

And Baronies, once held by robbers,

Are given to patriotic jobbers.

Uncompromising malediction

Rests on the Baronets of fiction;

In actual life they serve to link

A Party with the Street of Ink;

While Knighthood's latest honours fall

Upon the funniest men of all.

Yes, while our gratitude acclaims

The justly decorated names

Of peers like TENNYSON and LISTER,

There is much virtue in plain Mister.

The style and title deemed most fit

By DARWIN, HUXLEY, BURKE and PITT,

And later on by A.J.B.,

Are more than good enough for me.

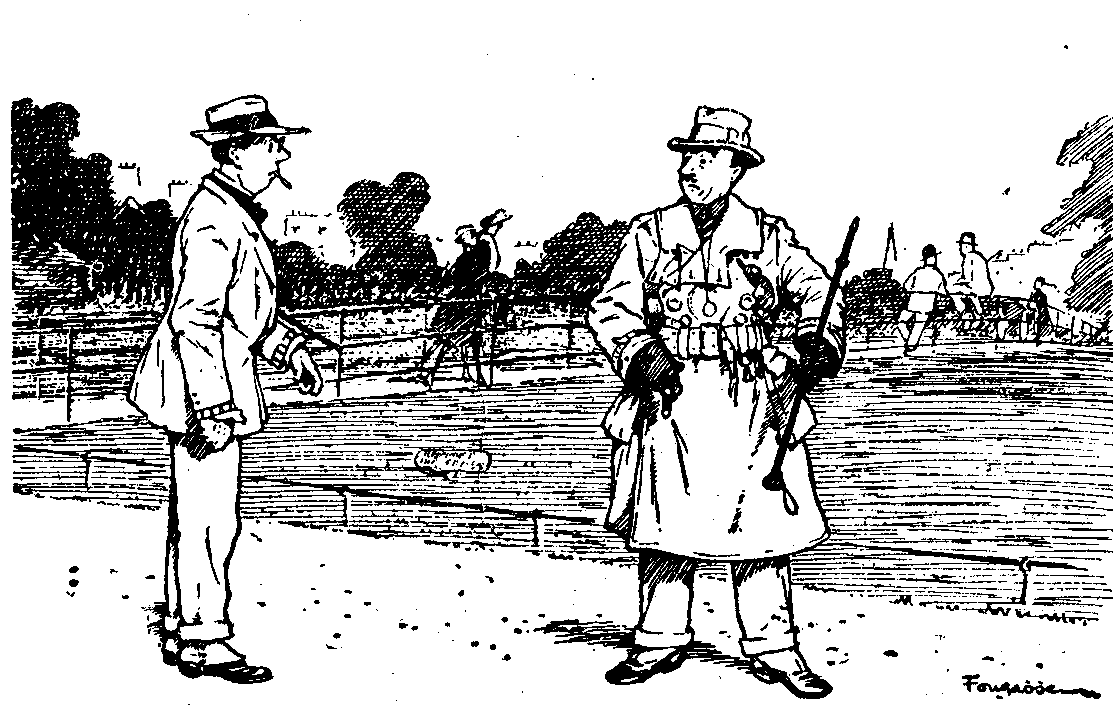

| Visitor. "WHAT'S THIS FELLOW DOIN' IN THE CORNER?" | Artist. "OH, HE'S THERE JUST TO HELP THE COMPOSITION." | |

| Visitor. "AWFULLY DECENT OF HIM—WHAT!" | ||

Last Thursday, at a registry-office, I obtained the favour of an interview with a domestic artist and was able (by reason of a previous conference with my friend Freshfield—like myself a demobilised bachelor author) to face the ordeal with some degree of confidence.

Mrs. Milton, widow, fifty-five, exceptional references, who proposed, if everything about me seemed satisfactory, to rule my household, was as suave as one has any right to expect nowadays; but when she dictated the terms I gathered that she would be sufficiently dangerous if roused.

She knew what bachelors were, she did, and wasn't going to take a place where a lot of comp'ny was kept.

I assured her on this point. My friend, Mr. Freshfield, I said, would come once a week, every Monday, to dine and sleep, but beyond that I should put no strain upon her powers of entertainment.

Mrs. Milton further said that she would require at least two afternoons and one evening a week. Here was my opportunity to appear generous.

"Two afternoons and one evening?" I said. "My dear friend and fellow-worker, you can have every Wednesday and Thursday from after breakfast on the former to practically dinner-time (eight o'clock) on the latter. No questions will be asked of you or of the piano or gramophone, both of which instruments you will find in smooth running order. I am away," I added, "every Wednesday and Thursday."

That clinched it. Hiding her surprise as well as she could under an irreproachable bonnet and toupee, Mrs. Milton expressed her readiness to accompany me then and there, and to superintend the disappearance of my coals and marmalade.

Perhaps you have guessed that I propose to spend every Wednesday night at Freshfield's place, and that the complete success of the scheme has been assured by the making of a similar agreement between Freshfield and a person holding corresponding views to those of Mrs. Milton.

Thus Freshfield and I have each secured the full seven days' attendance by a device pleasing to all concerned. After locking up the MELBA and GEORGE ROBEY records on Wednesday mornings and with the knowledge that the piano is past serious injury, I depart for Freshfield's (viâ the Club for lunch) each week with a light heart.

My collaborator is all for keeping this solution of a harassing problem to ourselves. I say "No." The general adoption of such a scheme, with alterations to suit individual cases, would, I think, be a nail in the coffin of Bolshevism in the home.

Mr. Wilson Rubs It In.

"The Echo de Paris says, 'Mr. Wilson believes he can play the rôle of the Popes of the middle ages. In the éclat of his public messages he tries to set peoples against governments.'"—Scots Paper.

"General Monash making an imposing figure on his grey horse, where he rode with General Hobbs and three Brigadiers."—Times.

The R.S.P.C.A. must look into this.

"GOLF BATTLE OF THE SEXES.

The latest Jack Johnson story is that he is training in Mexico City for a series of fights, which will take place in the bull-ring.

Ladies: Miss Cecil Leitch, Miss Chubb, Miss Barry, Mrs. McNair, Mrs. Jillard, Mrs. F.W. Brown, Miss Jones Parker and Mrs. Willock Pollen."—Daily Sketch.

We are rather sorry for Massa JOHNSON.

Bored Cadet (in Westminster Abbey). "LET'S SHOVE OFF NOW, MATER. HATE HANGIN' ROUND A PLACE WHERE ONE MIGHT BE BURIED SOME DAY!"

The acquiescence of the Coventry Peace Celebration Committee in the Bishop of COVENTRY'S view that the Lady GODIVA of their pageant should be fully clothed is leading not only to many innovations in the representations of history all over the country, but to a recrudescence of ecclesiastical power which is affording the liveliest satisfaction to Lord HUGH CECIL.

For already several other divines have followed suit. It is agreeable, for example, to the very reasonable wishes of the DEAN and Chapter of Westminster that the Westminster Peace Celebration Committee have decided that NELL GWYNN shall either be excluded from the Whitehall procession altogether or shall figure as a Mildmay deaconess.

Acting under the influence of a local curate, the Athelney Peace Celebration Committee have unanimously resolved that in these hard times, when (as the curate pointed out) food is not too plentiful, it would be better if KING ALFRED cooked the cakes properly and they were afterwards distributed.

So many watering-places claim CANUTE as their own that he may be expected to be multiplied exceedingly in the approaching Peace revels; but from more than one Pastoral Letter it may be gathered that the Episcopal Bench is very wisely in favour of the King's retirement from the margin of the ocean before his shoes are actually wet. It is held that in these days of leather-shortage and the need for economy no risks should be run with footwear.

Other laudable efforts in the direction of economy are to be made, again through the earnest solicitude of the Establishment, in connection with the impersonation of Sir WALTER RALEIGH and KING JOHN. With the purpose of saving Sir WALTER'S cloak from stain and possible injury the puddle at QUEEN ELIZABETH'S feet will be only a painted one, while, owing to the exorbitant price of laundry-work at the moment, it has been arranged that only a few of KING JOHN'S more negligible articles shall be consigned to the Wash.

Hun Duplicity in Paris.

"Count von Brockdorff-Rantzau replied simply, pointing to Herr Dandsbery and saying: 'I present to you Herr Landsberg.'"—The Star.

How oft I tried by smart intrigue

To do the British Army,

And dodge each rightly-termed Fatigue

Which nearly drove me barmy.

In vain! Whoever else they missed

My name was always on the list.

And so, while other minds were set

On smashing Jerry Bosch up

With rifle, bomb and bayonet,

I chiefly learned to wash-up,

To peel potatoes by the score,

Sweep out a room and scrub the floor.

Thus, now that I have left the ranks,

The plain unvarnished fact is

That through those three rough years, and thanks

To very frequent practice,

I, who was once a nascent snob,

Am master of the menial's job.

To-day I count this no disgrace

When "maids" have gone to blazes,

But take our late Eliza's place

And win my lady's praises,

As she declares in grateful mood

The Army did me worlds of good.

"So," said Albert Edward, "I clapped him on the back and said, 'You were at Geelong College in 1910, and your name's Cazenove, isn't it?'"

"To which he made reply, 'My name's Jones and I never heard of Geewhizz,' and knocked you down and trod on you for your dashed familiarity," said the Babe.

"Nothing of the sort. He was delighted to meet me again—de-lighted. He's coming to munch with us tomorrow evening, by the way, so you might sport the tablecloth for once, William old dear, and tell the cook to put it across Og, the fatted capon, and generally strive to live down your reputation as the worst Mess President the world has ever seen. You will, I know—for my sake."

Next morning, when I came down to breakfast, I found a note from him saying that he had gone to the Divisional Races with his dear old college chum, Cazenove; also the following addenda:—

"P.S.—If William should miss a few francs from the Mess Fund tell him I will return it fourfold ere night. I am on to a sure thing.

"P.P.S.—If MacTavish should raise a howl about his fawn leggings, tell him I have borrowed them for the day as I understand there will be V.A.D.'s present, and noblesse oblige."

At a quarter past eight that night he returned, accompanied by a pleasant-looking gunner subaltern, whom we gathered to be the Cazenove person. I say "gathered," for Albert Edward did not trouble to introduce the friend of his youth, but, flinging himself into a chair, attacked his food in a sulky silence which endured all through the repast. Mr. Cazenove, on the other hand, was in excellent form. He had spent a beautiful day, he said, and didn't care who knew it. A judge of horseflesh from the cradle, he had spotted the winner every time, backed his fancy like a little man and had been very generously rewarded by the Totalizator. He was contemplating a trip to Brussels in a day or so. Was his dear old friend Albert Edward coming?

His "dear old friend" (who was eating his thumb-nails instead of his savoury) scowled and said he thought not.

The gunner wagged his head sagely. "Ah, well, old chap, if you will bet on horses which roar like a den of lions you must take the consequences."

Albert Edward writhed. "That animal used to win sprints in England; do you know that?"

Mr. Cazenove shrugged his shoulders.

"He may have thirty years ago. All I'd back him to win now would be an old-age pension. Well, I warned you, didn't I?"

Albert Edward lost control. "When I'm reduced to taking advice on racing form from a Tasmanian I'll chuck the game and hie me to a monkery. Why, look at that bit of bric-à-brac you were riding to-day; a decent God-fearing Australian wouldn't be seen dead in a ten-acre paddock with it."

Mr. Cazenove spluttered even more furiously. "That's a dashed good horse I'll have you know."

"I am not alluding to his morals, but to his appearance," said Albert Edward; "I've seen better-looking hat-racks."

"I'd back him to lick the stuffing out of anything you've got in this unit, anyway," Cazenove snorted.

"Don't be rash, Charlie," Albert Edward warned; "your lucky afternoon has gone to your head. Why, I've got an old mule here could give that boneshaker two stone and beat him by a furlong in five."

The gunner sprang to his feet. "Done with you!" he roared. "Done with you here and now!"

Albert Edward appeared to be somewhat taken back. "Don't be silly, man," he soothed. "It's pitch dark outside and cut up with trenches. Sit down and have some more of this rare old port, specially concocted for us by the E.F.C."

But Mr. Cazenove was thoroughly aroused. "You're hedging," he sneered; "you're scared."

"Nonsense," said Albert Edward. "I have never known what fear is—not since the Armistice, anyhow. I am one of the bravest men I have ever met. What are you doing with all that money?"

"Putting it down for you to cover," said Cazenove firmly.

Albert Edward sighed. "All right, then, if you will have it so. William, old bean, I'm afraid I shall have to trouble you for a trifle more out of the Mess Fund. Noblesse oblige, you know."

MacTavish and the Babe departed with the quest to prepare his mount for the ordeal, while Albert Edward and I sought out Ferdinand and Isabella, our water-cart pair. Isabella was fast asleep, curled up like a cat and purring pleasantly, but Ferdinand was awake, meditatively gnawing through the wood-work of his stall. With the assistance of the line-guard we saddled and bridled him; but at the stable door he dug his toes in. It was long past his racing hours, he gave us to understand, and his union wouldn't permit it. He backed all round the standings, treading on recumbent horses, tripping over bails, knocking uprights flat and bringing acres of tin roofing clattering down upon our heads, Isabella encouraging him with ringing fanfares of applause.

At length we roused out the grooms and practically carried him to the starting-point.

"You've been the devil of a time," William grumbled. "Cazenove's been waiting for twenty minutes. See that light over there? That's where MacTavish is. He's the winning-post. Keep straight down the mud-track towards it and you'll be all right. Don't swing sideways or you'll get bunkered. Form line. Come up the mule. Back, Cazenove, back! Steady. Go!"

The rivals clapped heels to their steeds and were swallowed up in the night. I looked at my watch, the hands pointed to 10.30 exactly. William and I lit cigarettes and waited. At 10.42 MacTavish walked into us, his lamp had given out and he wanted a new battery.

"Who won?" we inquired.

"Won?" he asked. "They haven't started yet, have they?"

"Left here about ten minutes ago," said William. "Do you mean to say you've seen nothing of them?"

At that moment two loud voices, accompanied by the splash of liquid and the crash of tin, struck our ears from different points of the compass.

"Sounds to me as if somebody had found a watery grave over to the left," said the Babe.

"Sounds to me as if somebody had returned to stables over to the right," said I.

We trotted away to investigate. 'Twas as I thought; Ferdinand had homed to his Isabella and was backing round the standings once more, trailing the infuriated Albert Edward after him, sheets of corrugated iron falling about them like leaves in Vallombrosa.

"Bolted straight in here and scraped me off against the roof," panted the latter. "Suppose the confounded apple-fancier won ages ago, didn't he?"

"He's upside down in the Tuning Fork trench system at the present moment," said I. "The Babe and the grooms are digging him out. If you hurry up you'll win yet."

We roused out the guard, bore the reluctant Ferdinand back to the course and by eleven o'clock had restarted him. At 11.10 William returned to report that the digging party had salved the Cazenove pair and got them going again.

"Too late," said I; "Albert Edward must have won in a walk by now. He left here at ..."

The resounding clatter of falling [pg 361] sheet-iron cut short my words. Ferdinand had, it appeared, returned to stables once more.

Suddenly something hurtled out of the gloom and crashed into us. It was the Babe.

"What's the matter now? Where are you going?" we asked.

"Wire-cutters, quick!" he gasped and hurtled onwards towards the saddle-room.

"Hello there!" came the hail of MacTavish from up the course. "I s-say, what about this blessed race? I'm f-f-rozen s-s-tiff out here. I'm about f-f-fed up, I t-tell you."

William groaned. "As if we all weren't!" he protested. "If all the Mess Funds for the next three weeks weren't involved I'd make the silly fools chuck it. Here, you, run and tell Albert Edward to get a move on."

I found Ferdinand rapidly levelling the remainder of the standings, playing his jockey at the end of his reins as a fisherman plays a salmon.

"This cursed donkey won't steer at all," Albert Edward growled. "Sideslips all over the place like a wet tyre. Has Cazenove won yet?"

"Not yet," said I. "He's wound up in the Switch Line wire entanglements now. The Babe and the wrecking gang are busy chopping him out. There's still time."

"Then drag Isabella out in front of this brute," said he. "Quick, man, quick!"

At 11.43, by means of a brimming nose-bag, I had enticed Isabella forth, and the procession started in the following order: First, myself, dragging Isabella and dangling the bait. Secondly, Isabella. Thirdly, the racers, Ferdinand and Albert Edward, the latter belting Isabella with a surcingle whenever she faltered. Lastly, the line-guard, speeding Ferdinand with a doubled stirrup-leather. We toiled down the mud. track at an average velocity of .25 m.p.h., halting occasionally for Isabella to feed and the line-guard to rest his arm. I have seen faster things in my day.

Then, just as we were arriving at our journey's end we collided with another procession. It was the wrecking gang, laden with the implements of their trade (shovels, picks, wire-cutters, ropes, planks, waggon-jacks, etc.), and escorting in their midst Mr. Cazenove and his battered racehorse. Both competitors immediately claimed the victory:—

"Beaten you this time, Albert Edward, old man."... "On the contrary, Charles, old chap, I won hands down."... "But, my good fellow, I've been here for hours."... "My dear old thing, I've been here all night!"... "Do be reasonable."... "Don't be absurd."

"Oh, dry up, you two, and leave it to the winning-post to decide," said William.

"By the way, where is the winning-post?"

"The winning-post," we echoed. "Yes, where is he?"

"Begging your pardon, Sir," came the voice of the Mess orderly, "but if you was referring to Mister MacTavish he went home to bed half-an-hour ago."

Potential President of the Royal Academy. "AND HERE, AUNTIE, WE GET THE SIDE ELEVATION."

Auntie. "HOW DELIGHTFULLY THOROUGH! I'D NO IDEA THAT ARCHITECTS DID THE SIDES AS WELL."

Another Impending Apology.

"A sub-department of Scotland Yard ... which looks after Kings and visiting potentates, Cabinet Ministers and Suffragettes, spies, anarchists, and other 'undesirables.'"—Daily Paper.

"The custodian smothered the ball, and after a Ruby scrimmage the City goal escaped."—Provincial Paper.

A much prettier word than the other.

"Teacher (juniors); £1 monthly."—Advt. in Liverpool Paper.

Who says there are no prizes in the teaching profession?

When I had seen ten thousand pass me by

And waved my arms and wearied of hallooing,

"Ho, taxi-meter! Taxi-meter, hi!"

And they hied on and there was nothing doing;

When I was sick of counting dud by dud

Bearing I know not whom—or coarse carousers,

Or damsels fairer than the moss-rose bud—

And still more sick at having bits of mud

Daubed on my new dress-trousers;

I went to dinner by the Underground

And every time the carriage stopped or started

Clung to my neighbour very tightly round

The neck till at Sloane Square his collar parted.

I saw my hostess glancing at my socks,

Surprised perhaps at so much clay's adherence

And, still unnerved by those infernal shocks,

Said, "I was working in my window-box;

Excuse my soiled appearance."

But in the morn I found a silent square

And one tall house with all the windows shuttered,

The mansion of the Marquis of Mayfair,

And "Here shall be the counter-stroke," I muttered;

"Shall not the noble Marquis and his kin

Make feast to-night in his superb refectory,

And then go on to see 'The Purple Sin'?

They shall." I sought a taxi-garage in

The Telephone Directory.

"Ho, there!" I cried within the wooden hutch;

"Hammersmith House—a most absurd dilemma—

His lordship's motor-cars have strained a clutch,

And taxis are required at 8 pip emma

(Six of your finest and most up-to-date,

With no false starts and no foul petrol leaking),

To bear a certain party of the great

To the Melpomene at ten past eight.

Thompson, the butler, speaking."

They came. And I at the appointed hour

Watched them arrive before the muted dwelling

And heard some speeches full of pith and power

And saw them turn and go with anger swelling;

Save only one who, spite his rude dismay,

Like a whipped Hun, made traffic of his sorrow

And shouted, "Taxi, Sir?" I answered "Nay,

I do not need you, jarvey, but I may

Be disengaged to-morrow."

EVOE.

The Punishment of Greed.

"Large quantity of new Block Chocolate offered cheap; cause ill-health."—Manchester Evening News.

"Miss M. Albanesi, daughter of the well-known singer, Mme. Albanesi."—Daily Paper.

Not to be confused with Mme. ALBANI, the popular novelist.

"The Portuguese retreated a step. His head flew to his hip-pocket. But he was a fraction of a second too late."—The Scout.

Many a slip 'twixt the head and the hip.

Tuesday, April 29th.—When the House of Commons re-assembled this afternoon a good many gaps were noticeable on the green benches. They were not due, however, to the New Year's Honours, which made a belated appearance this morning, for not a single Member of Parliament has been ennobled. The notion that not one of the seven hundred is worthy of elevation is, of course, unthinkable. But by-elections are so chancy.

Mr. JEREMIAH MACVEAGH still has some difficulty in realising that the Irish centre of gravity has shifted from Westminster to Dublin. He indignantly refused to accept an answer to one of his questions from little Mr. PRATT, and loudly demanded the corporeal presence of the CHIEF SECRETARY. Mr. MACPHERSON, however, considers that his duty requires him to remain in Ireland, where Mr. MACVEAGH'S seventy Sinn Fein colleagues are keeping him sufficiently busy.

In explaining the swollen estimates of the Ministry of Labour, Sir ROBERT HORNE pointed out that it is now charged with the functions formerly appertaining to half-a-dozen other Departments. He has indeed become a sort of administrative Pooh-Bah. Unlike that functionary, however, he was not "born sneering." On the contrary, he made a most sympathetic speech, chiefly devoted to justifying the much-abused unemployment donation, which accounts for twenty-five out of the thirty-eight millions to be spent by his Department this year. But let no one mistake him for a mere HORNE of Plenty, pouring out benefits indiscriminately upon the genuine unemployed and the work-shy. He has already deprived some seventeen thousand potential domestics of their unearned increment, and he promises ruthless prosecution of all who try to cheat the State in future.

Criticism was largely silenced by the Minister's frankness. Sir F. BANBURY, of course, was dead against the whole policy, and demanded the immediate withdrawal of the civilian grants; but his uncompromising attitude found little favour. Mr. CLYNES thought it would have been better for the State to furnish work instead of doles, but did not explain how in that case private enterprise was to get going. France's experience with the ateliers nationaux is not encouraging, though 1919, when "demobbed" subalterns turn up their noses at £250 a year, is not 1848.

Wednesday, April 30th.—Mr. AUSTEN CHAMBERLAIN, returning to the Exchequer after an interval of thirteen years, made a much better Budget speech than one would have expected. It was longer, perhaps, than was absolutely necessary. Like the late Mr. GLADSTONE, he has a tendency to digress into financial backwaters instead of sticking to the main Pactolian stream. His excursus upon the impracticability of a levy on capital was really redundant, though it pleased the millionaires and reconciled them to the screwing-up of the death-duties. Still, on the whole, he had a more flattering tale to unfold than most of us had ventured to anticipate, and he told it well, in spite of an occasional confusion in his figures. After all, it must be hard for a Chancellor who left the national expenditure at a hundred and fifty millions and comes back to find it multiplied tenfold not to mistake millions for thousands now and again.

On the whole the Committee was well pleased with his performance, partly because the gap between revenue and expenditure turned out to be a mere trifle of two hundred millions instead of twice or thrice that amount; partly because there was, for once, no increase in the income-tax; but chiefly, I think, for the sentimental reason that in recommending a tiny preference for the produce of the Dominions and Dependencies Mr. CHAMBERLAIN was happily combining imperial interests with filial affection.

Almost casually the CHANCELLOR announced that the Land Values Duties, the outstanding feature of Mr. LLOYD GEORGE'S famous Budget of 1909, were, with the approval of their author, to be referred to a Select Committee, to see if anything could be made of them. If only Mr. ASQUITH had thought of that device when his brilliant young lieutenant first propounded them! There would have been no quarrel between the two Houses: the Parliament Act would never have been passed, and a Home Rule Act, for which nobody in Ireland has a good word, would not now be reposing on the Statute-Book.

In the absence of any EX-CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER the task of criticism was left to Mr. ADAMSON, who was mildly aggressive and showed a hankering after a levy on capital, not altogether easy to reconcile with his statement that no responsible Member of the Labour Party desired to repudiate the National Debt. Mr. JESSON, a National Democrat, was more original and stimulating. As a representative of the Musicians' Union he is all for harmony, and foresees the time when Capital and Labour shall unite their forces in one great national orchestra, under the directing baton of the State.

At the instance of Lord STRACHIE the House of Lords conducted a spirited little debate on the price of milk. It appears that there is a conflict of jurisdiction between the FOOD-CONTROLLER and the MINISTER OF AGRICULTURE, and that the shortage in the supply of this commodity must be ascribed to the overlapping of the Departments.

Thursday, May 1st.—Sinn Fein has decreed that nobody in Ireland should do any work on May Day. Messrs. DEVLIN and MACVEAGH, however, being out of the jurisdiction, demonstrated their independence by being busier than ever. The appointment of a new Press Censor in Ireland furnished them with many opportunities at Question-time for the display of their wit, which some of the new Members seemed to find passably amusing.

Mr. DEVLIN'S best joke was, however, [pg 366] reserved for the Budget debate, when, in denouncing the further burdens laid on stout and whisky, he declared that Ireland was, "apart from political trouble," the most peaceful country in the world.

The fiscal question always seems to invite exaggeration of statement. The CHANCELLOR'S not very tremendous Preference proposals were denounced by Sir DONALD MACLEAN as inevitably leading to the taxation of food and to quarrels with foreign countries. Colonel AMERY, on the other hand, waxed dithyrambic in their praise, and declared that by taking twopence off Colonial tea the Government were not only consecrating the policy of Imperial Preference, but were "putting the coping-stone on it."

The Minister of Labour (anxious to find work for the ex-munitionette drawing unemployment pay). "HERE, MODOM, IS A CHARMING MODEL WHICH WOULD SUIT YOU, IF I MAY SO PUT IT, DOWN TO THE GROUND."

The continued domination of the Russians in the domain of the ballet has already excited a certain amount of not unfriendly criticism. But our Muscovite visitors are not to be allowed to have it all their own way, and we understand that negotiations are already on foot with a view to enabling the Irish Ballet to give a season at a leading London theatre in the near future.

The Irish Ballet, which is organised on a strictly self-determining basis, is one of the outcomes of the Irish Theatre, but derives in its essentials directly from the school established by Cormac, son of Art. That is to say it is in its aims, ideals and methods permeated by the Dalecarlian, Fomorian, Brythonic and Firbolgian impulse. Mr. Fergal Dindsenchus O'Corkery, the Director, is a direct descendant of Cuchulinn and only uses the Ulidian, dialect. Mr. Tordelbach O'Lochlainn, who has composed most of the ballets in the répertoire, is a chieftain of mingled Dalcassian and Gallgoidel descent. The scenery has been painted by Mr. Cathal Eochaid. MacCathamhoil, and the dresses designed by Mr. Domnall Fothud O'Conchobar.

The artists who compose the troupe have all been trained during the War at the Ballybunnion School in North Kerry, and combine in a wonderful way the sobriety of the Delsartean method with the feline agility of that of Kilkenny. Headed by the bewitching Gormflaith Rathbressil, and including such brilliant artists as Maeve Errigal, Coomhoola Grits, Ethne O'Conarchy, Brigit Brandub, Corcu and Mocu, Diarmid Hy Brasil, Murtagh MacMurchada, Aillil Molt, Mag Mell and Donnchad Bodb, they form a galaxy of talent which, alike for the euphony of its nomenclature and the elasticity of its technique, has never been equalled since the days of ST. VITUS.

We have spoken of the work of Mr. O'Lochlainn, who is responsible for the three-act ballet, Brian Boruma; a fantasy on the Brehon laws, entitled The Gardens of Goll; Poulaphuca, and the Roaring of O'Rafferty; but the repertory also includes notable and impassioned compositions by Ossian MacGillycuddy, Aghla Malachy, Carolan MacFirbis and Emer Sidh. The orchestra employed differs in many respects from that to which we are accustomed, the wood-wind being strengthened by a quartet of Firbolg flutes and two Fodlaphones, while the brass is reinforced by a bass bosthoon, an instrument of extraordinary depth and sonority, and the percussion by a group of Dingle drums.

But enough has been said to show that the Irish ballet is assured in advance of a cordial reception from all admirers of the neo-Celtic genius.

"A Bill has been introduced in Florida providing that 'from and after equal suffrage has been established in Florida it shall be lawful for females to don and wear the wearing apparel of man as now worn publicly by him.'"—Western Morning News.

Happily they cannot take the breeks off a Highlander.

Biddick has placed me in a most awkward position. I am a proud man; I cannot bring myself to accept a gift of money from anybody. And yet I cannot help feeling I should be justified in taking the guinea he has sent me.

Biddick is a journalist. I was discussing the inflation of prices and asking his advice as to how to increase one's income. "Why not write something for the Press, my dear fellow?" he said. "Five hundred words with a catchy title; nothing funny—that's my line—but something solid and practical with money in it; the public's always ready for that. Take your neighbour, old Diggles, and his mushroom-beds, for instance. Thriving local industry—capital copy. Try your hand at half a column, and call it 'A Fortune in Fungus.'"

"I 'm afraid I know nothing about mushrooms, with the exception of the one I nearly died of," I replied, "and I'm not sufficiently acquainted with Mr. Diggles to venture to invite his confidence respecting his business."

"My dear man, I don't ask you to tell Diggles you're going to write him up in the newspapers; he'd kick you off the premises; he doesn't want his secrets given away to competitors. Just dodge the old man round the sheds, get into conversation with his staff, keep your eyes open generally and you'll pick up as much as you want for half a column. And when you've got your notes together bring 'em along to me. I'll put 'em shipshape for you."

I thanked him very gratefully.

The mushroom-sheds are situated in a field some distance from my residence, and I found it rather a fatiguing walk. After tedious watching in a cramped position through a gap in the hedge I saw Mr. Diggles emerge from a shed and move away from my direction. I lost no time in creeping forward under cover of my umbrella towards an employee, who was engaged in tossing manure. I drew out my note-book and interrogated him briefly and briskly.

"Do you rear from seeds or from cuttings?" I asked him. He scratched his head and appeared in doubt. "Are your plants self-supporting," I went on, "or do you train them on twigs? What would be the diameter of your finest specimen?" He continued in [pg 367] doubt. I adopted a conversational manner. "I suppose you'll be potting off soon? You must get very fond of your mushrooms. I think one always gets fond of anything which demands one's whole care and attention. I wonder if I might have a peep at your protégés?"

I edged towards the door of one of the sheds, but he made no attempt to accompany me. Instead he put his hands to his mouth and shouted, "Hi, maister!"

Mr. Diggles promptly responded to the summons. There was no eluding him. I put my note-book out of sight and inquired if he could oblige me with a pound of fresh-culled mushrooms. He could, and he did. I paid him four-and-sixpence for them, the control price presumably, but he gave me no invitation to view the growing crops. I retraced my steps without having collected even an opening paragraph for "A Fortune in Fungus."

The next day found me again near the sheds. Mr. Diggles was nowhere in sight. I approached unobtrusively through the hedge and accosted a small boy.

"Hulloa, my little man," I said, "what is your department in this hive of industry? You weed the mushrooms, perhaps, or prune them?" He seemed shy and offered no answer. "Perhaps you hoe between the plants or syringe them with insecticide?"

Still I could not win his confidence, so I tried pressing sixpence into his palm. "Between ourselves, what are the weekly takings?" I said. He pocketed the coin and put his finger on his lips.

"Belge," he said. Then he bolted into a shed and returned accompanied by Mr. Diggles. There was nothing for it but to purchase another pound of mushrooms. I was no nearer "A Fortune in Fungus" than before.

Two days later, having received apparently reliable information that Mr. Diggles was confined to his bed with influenza, I ventured again to visit the sheds. I was advancing boldly across the field when to my consternation he suddenly appeared from behind a hayrick. I was so startled that I turned to fly, and in my precipitancy tripped on a tussock and fell. Mr. Diggles came to my assistance, and, when he had helped me to my feet and brushed me down with a birch broom he was carrying, I could do nothing less than buy another pound of his mushrooms.

I felt it was time to consult Biddick. He was sitting at his desk staring at a blank sheet of paper. His fingers were harrowing his hair and he looked distraught.

"Excuse the interruption," I said, "but this 'Fortune in Fungus' is ruining me;" and I related my experience.

At the finish Biddick gripped my hand and spoke with some emotion. "Dear old chap," he said, "it's my line, after all. It's funny. If only I can do it justice;" and he shook his fountain-pen.

This morning I received a guinea and a newspaper cutting entitled "A Cadger for Copy," which may appeal to some people's sense of humour. It makes none to mine. In the flap of the envelope Biddick writes: "Halves, with best thanks."

Upon consideration I shall forward him a simple formal receipt.

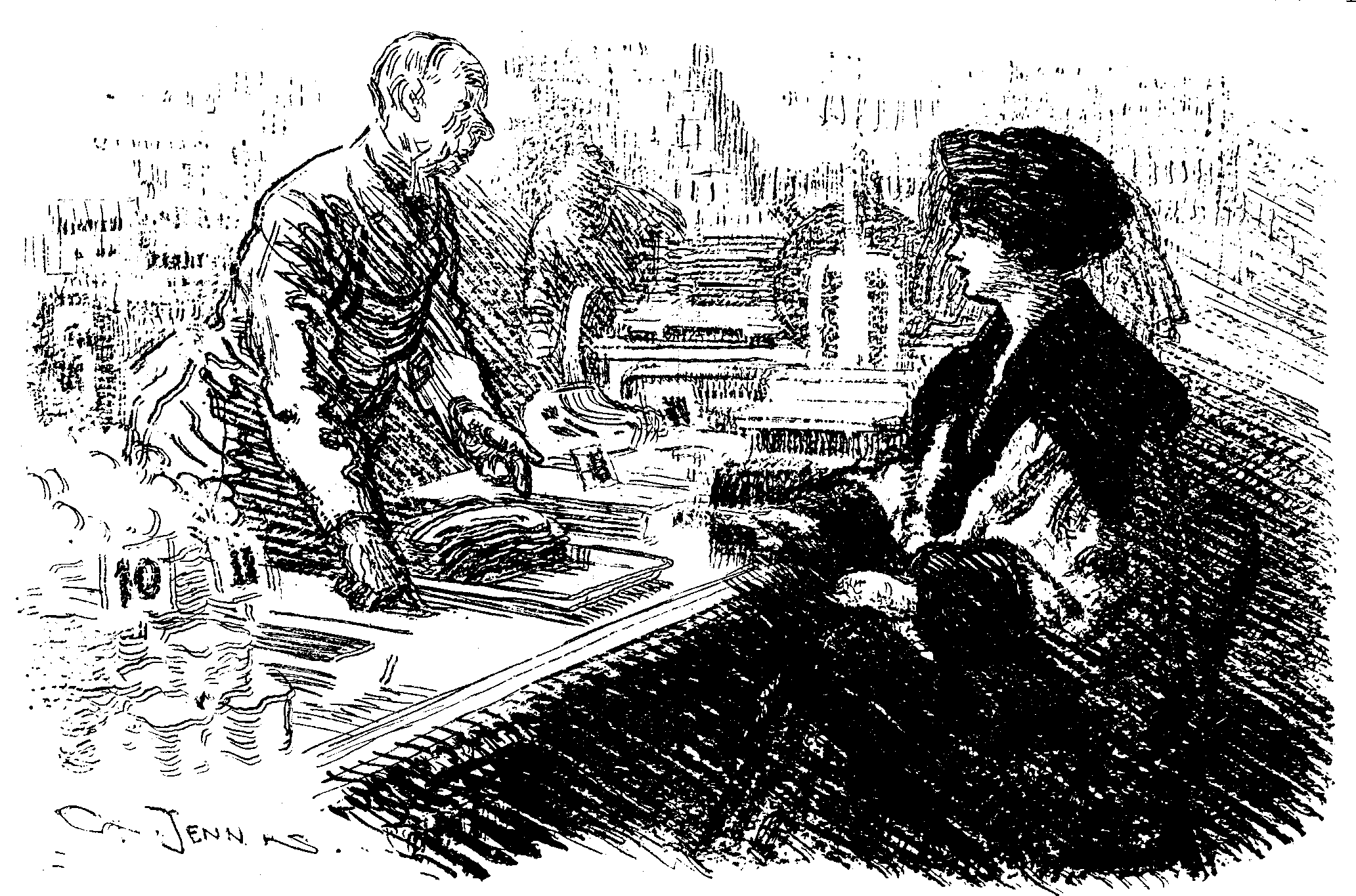

"IT LOOKS QUITE LIKE PRE-WAR BACON."

"ON THE CONTRARY, MADAM, PERMIT ME TO ASSURE YOU IT IS OUR FINEST 'POST-BELLUM STREAKY.'"

From a bookseller's catalogue:—

"THE ART OF TATTING.

This book is intended for the woman who has time to spare for reading, Tatting being such quick and easy work that busy fingers can do both at the same time."

An edition in Braille would appear to be contemplated.

The great Bacteriologist entered the lecture-room and ascended the platform. A murmur of astonishment ran round the audience as they beheld, not the haggard face of a man who daily risked the possibility of being awarded the O.B.E., but the calm and smiling countenance of one who had succeeded where other scientists, even of Anglo-American reputation, had failed.

In an awed silence this remarkable man placed on the table a dish, somewhat like a soup-plate in appearance, and carefully removed its glass cover.

"In this dish, gentlemen," said the Professor, "we have the Agar-Agar, which is without doubt the best bacteriological culture medium yet discovered and is especially useful in growing a pathogenic organism such as we are about to test this afternoon."

Then taking a glass rod, to the end of which was attached a small piece of platinum wire, the lecturer proceeded to scrape a little of the growth from off the Agar-Agar. Having done this he quickly deposited it in a test-tube half full of distilled water, which he then heated over a Bunsen burner. Finally, with the aid of a hypodermic syringe, a little of the liquid was injected into two sleepy-looking guinea-pigs, and with bated breath the result of the test was awaited.

Suddenly, without any warning, the two little animals rose on their hind legs and violently clutched each other by any part of the body on which they could get a grip. Before the astounded gaze of the onlookers they swayed, nearly fell, then went round in circles, at the same time executing every sort of conceivable contortion.

A great cheer burst from the audience. From all sides a rush was made for the platform, and the Professor was carried shoulder-high round the room.

The Jazz germ had been discovered at last.

Pekinese (who has been accidentally pushed into the gutter by gigantic bloodhound). "AND YOU MAY THANK YOUR STARS I'VE GOT A MUZZLE ON!"

A Friendly Offer.

"A French Gentleman would like to make acquaintance with and English one to improve the English language."—French Provincial Paper.

"Ste. Geneviève (422-572), born just outside Paris, spent a long life in the city."—Daily Paper.

Wherever it was spent, it was clearly a long life.

"—— College is the chosen home, the favoured haunt of educational success. Our staff is composed of lineal descendants of poets, seers, or savants, and it is the intention of this formidable phalanx of intellectuals to drive the whole world before them! We, of course, will say that these classes will be famous, and well worth attending. In Carlyle especially, the undersigned, with due modesty, expects to constitute himself a Memnon, and to receive the sage of Chelsea's martial pibroch from Hades, transmit it to the listeners, and to thrill them to the very marrow of their bones!"—Advt. in Indian Paper.

We should like to hear what the sage's martial pibroch has to say about the advertiser's "due modesty."

Among the many privileges which I propose to claim as a set-off for what are called advancing years is a greater laxity in quotation. When I have made a quotation I mean that that shall be the quotation, and I don't intend to be driven either to the original source or to cyclopaedias of literature for verification. DANTE, for instance, is a most prolific fount of quotations, especially for those who do not know the original Italian. If I have quoted the words "Galeotto fu il libro e chi lo scrisse" once, I have quoted them a hundred times, always with an excellent effect and often giving the impression that I am an Italian scholar, which I am not. But surely it is not usual to abstain from a quotation because to use it would give a false impression? I am perfectly certain, for instance, that there are plenty of Italians who quote Hamlet, but know no more of English than the words they quote, so I dare say that brings us right in the end.

Then there is the quotation about "a very parfitt gentil knight," or words to that effect. At the moment of writing it down I felt that my version was so correct that I would go to the scaffold for it; but at this very instant a doubt insinuates itself. Is "parfitt" with two "t's" the right spelling?

It is related somewhere that TENNYSON and EDWARD FITZGERALD once conspired together to see which of them could write the most Wordsworthian line, and that the result was:—

"A Mr. Wilkinson, a clergyman."

But there was no need for TENNYSON to go beyond his own works in search of such an effect. He had already done the thing; and this was his effort, which occurs in The May Queen:—

"And that good man, the clergyman, has told me words of peace."

This sounds as if it could not be defeated or matched, but matched it certainly was in Enoch Arden. After describing Enoch Arden's death and the manner in which he "roll'd his eyes" upon Miriam, the bard informs us:—

"So past the strong heroic soul away.

And when they buried him the little port

Had seldom seen a costlier funeral."

But I feel that I have strayed beyond my purpose, which was to claim a certain mitigated accuracy in quotation for those who suffer from advancing years.

"——, chambermaid at the —— Hotel, ——, was charged yesterday with stealing two diamond rings and a diamond and sapphire broom worth £80."—Daily Paper.

Yet Mr. CHAMBERLAIN refuses to impose a Luxury Tax.

From a list of the German Peace-delegates:—"Baron von Lersner, chief of the preliminary mission and ex-secretary of the German Embassy in Washington. He was also formerly attached to the German Embassy in Wales."—Belfast News Letter.

This sounds like another injustice to Ireland.

Scientific Uncle. "DO YOU KNOW, CHILDREN, THAT AT ONE TIME, LONG AGO, WE USED TO HAVE FIVE TOES ON EACH HAND, AND LIVE IN TREES?"

Niece. "WE WON'T TELL ANYBODY, UNCLE."

The 23rd. To-day, my son,

Two turgid years ago,

Your father battled with the Hun

At five A.M. or so;

This was the day (if I exclude

A year of painful servitude

Under the Ministry of Food)

I struck my final blow.

Ah, what a night! The cannon roared;

There was no food to spare;

And first it froze and then it poured;

Were we dismayed? We were.

Three hundred yards we went or more,

And, when we reached, through seas of gore,

The village we were fighting for,

The Germans were not there.

But miles behind a 9·2

Blew up a ration dump;

Far, far and wide the tinned food flew

From that tremendous crump:

And one immense and sharp-toothed tin

Came whistling down, to my chagrin,

And caught me smartly on the shin—

By Jove, it made me jump.

A hideous wound. The blood that flowed!

It was a job to dress;

I hobbled bravely down the road

And reached a C.C.S.;

Nor was I so obsessed with gloom

At leaving thus the field of doom

As one might easily assume

From stories in the Press.

Though other soldiers as they fell—

Or so the papers say—

Cried, "GEORGE for England! Give 'em hell!"

(It was ST. GEORGE'S Day),

Inspiring as a Saint can be,

I should not readily agree

That anyone detected me

Behaving in that way.

Such is the tale. And, year by year,

I shall no doubt relate

For your fatigued but filial ear

The history of this date;

Yet, though I do not now enhance

The crude events of that advance,

There is a wild fantastic chance

That they will grow more great.

So be you certain while you may

Of what in fact occurred,

And if I have the face to say

On some far 23rd

That on this day the war was won,

That I despatched a single Hun,

Or even caught a glimpse of one—

Don't you believe a word.

A.P.H.

Another Impending Apology.

"Miss —— looked sweetly pretty in an emerald-green satin (very short) skirt, white blouse, and emerald handkerchief tied over her head—an Irish Colleen, and a bonie one too!"—Colonial Paper.

"According to a Vienna message, the Government has introduced a Bill dealing with the former reigning Mouse of Austria."—Provincial Paper.

Alas, poor KARL! Ridiculus mus.

"Wanted one hour daily from ten to eleven morning at convenience an English Talking Family for practice of talking. Remuneration twenty rupees per mensem."—Times of India.

We know one or two "talking families" that we should be glad to export.

"In finding the defendant £3, Mr. Price told the defendant that he would get into serious trouble if he persisted in his conduct."—Evening Paper.

And he may not meet such a generous magistrate next time.

"Englishman, well educated, desires afternoon engagement; experienced in the care of children; good needlewoman; or would assist light housework."—Canadian Paper.

We hope we shall hear no further complaints from Canada that Englishmen are not adaptable.

I was sitting in the Club, comfortably concealed by sheets of a well-known journal, when two voices, somewhere over the parados of the deep arm-chair, broke in upon my semi-consciousness.

"... Then poor old Tubby, who hasn't recovered from his 1918 dose of shell-shock, got a go of claustrophobia and felt he simply had to get out of the train."

The speaker paused and I heard the clink of glass.

"Well?" said the other voice.

"So, before we could flatten him out, he skipped up and pulled the communicator thing and stopped the train; consequently we ran into Town five minutes behind time. There was the deuce of a buzz about it."

"What's five minutes in this blissful land of lotus-eaters? Why, I've known the Calais-Wipers express lose itself for half-a-day without a murmur from anyone, unless the Brigadier had run out of bottled Bass."

"But, my dear fellow," the first voice expostulated, "this was the great West of England non-stop Swallowtail; runs into Town three minutes ahead of time every trip. Habitués of the line often turn an honest penny by laying odds on its punctuality with people who are strangers to the reputation of this flier."

"A pretty safe thing to bet on, eh?" said the other voice. Again there was the faint clink of glass and then the voices drifted into other topics, to which, having re-enveloped myself in my paper, I became oblivious.

A few days later I was called away from London, with Mr. Westaby Jones, to consult in a matter of business. Mr. Westaby Jones is a member of the Stock Exchange and, amongst other trivial failings, he possesses one which is not altogether unknown in his profession. He cannot resist a small wager. On several occasions he has gambled with me and shown himself to be a gentleman of considerable acumen.

Our business was finished and we were on the way back to Town by the great West of England non-stop Swallowtail. We had lunched well and discussed everything there was to discuss. It was a moment for rest. I unfolded my paper and proceeded to envelop myself in the usual way.

I seemed to hear the chink of glasses ... a voice murmured, "A pretty safe thing to bet on."

Then in a dreamy sort of manner I realised that Fate had delivered Westaby Jones into my hands. When we were within twenty miles of London I opened the campaign. I grossly abused the line on which we were travelling and suggested that anybody could make a fortune by assuming that its best train would roll in well after the scheduled time.

Westaby Jones, having privily ascertained that the engine-driver had a minute or so in hand, immediately pinned me down to what he thought (but wisely did not say) were the wild inaccuracies of an imbecile. He did it to the extent of twenty-five pounds, and I sat back with the comfortable feeling of a man who will shortly have a small legacy to expend. At the moment which I had calculated to be most auspicious I suddenly threw off the semblance of boredom, rose up, lurched across the carriage and pulled the communication cord. (For the benefit of those who have not done this I may say that the cord comes away pleasantly in the hand and, at the same time, gives one a piquant feeling of unofficial responsibility.) Westaby Jones was, for a stockbroker, obviously astonished.

"What on earth are you doing?" he exclaimed.

"Sit down," I said; "this is my improved exerciser."

"But you'll stop the train," he shouted.

"Never mind," I replied; "what's a fine of five pounds compared to physical fitness? Besides," I added significantly, "it may be a good investment after all."

For perhaps twenty seconds there was the silent tension of expectation in the air and then I realised with a shock that the train did not show any signs of slackening speed. It was, if anything, going faster. I snatched frantically at the cord and pulled about half-a-furlong into the carriage. We flashed past Ealing like a rocket, and I desperately drew in coils and coils of the communicator until I and Westaby Jones resembled the Laocoon. It was no good. Smoothly and irresistibly we glided into the terminus and drew up at the platform three minutes ahead of time.

I have paid Westaby Jones, who was unmannerly enough to look pleased. I have also corresponded with the railway company, claiming damages on the grounds of culpable negligence. Unfortunately they require more evidence than I am prepared to supply of the reasonable urgency of my action.

From a theatre programme:—

"The name of the actual and responsible Manager of the premises must be printed at least once during every performance to ensure its being in proper order."

So that explains the noise going on behind the scenes.

The Cuckoo has arrived and will sing as announced.

One of the results of the arrival of the Cuckoo is the prevalence of notices, for those that have eyes to see, drawing attention to the ineligible character of nests. These take a variety of forms—such as "All the discomforts of home," "Beware of mumps," "We have lost our worm cards," "Serious lining-shortage"—but the purpose of each is to discourage the Cuckoo from depositing an egg where it is not wanted.

From all parts of the country information reaches us as to the odd nesting-places of wrens and robins. A curious feature is the number of cases where letter-boxes have been chosen, thus preventing the delivery of letters, and in consequence explaining why so many letters have not been answered. Even the biggest dilatory correspondent is not ashamed to take advantage of the smallest bird.

The difficulty of obtaining muzzles is very general and many dog-owners have been hard put to it to comply with the regulation. From these, however, must be excepted those who possess wire-haired terriers, from whose coats an admirable muzzle can be extracted in a few minutes.

The statement of a telephone operator, that "everything gives way to trunks," is said to have caused great satisfaction in the elephant house at the Zoo.

Please be careful where you tread,

The fairies are about;

Last night, when I had gone to bed,

I heard them creeping out.

And wouldn't it be a dreadful thing

To do a fairy harm?

To crush a little delicate wing

Or bruise a tiny arm?

They 're all about the place, I know,

So do be careful where you go.

Please be careful what you say,

They're often very near,

And though they turn their heads away

They cannot help but hear.

And think how terribly you would mind

If, even for a joke,

You said a thing that seemed unkind

To the dear little fairy folk.

I'm sure they're simply everywhere,

So promise me that you'll take care.

R.F.

Harold (after a violent display of affection). "'TISN'T 'COS I LOVE YOU—IT'S 'COS YOU SMELL SO NICE."

(By Mr. Punch's Staff of Learned Clerks.)

The Great Man is, I suppose, among the most difficult themes to treat convincingly in fiction. To name but one handicap, the author has in such cases to postulate at least some degree of acquaintance on the part of the reader with his celebrated subject. "Everyone is now familiar," he will observe, "with the sensational triumph achieved by the work of X——;" whereat the reader, uneasily conscious of never having heard of him, inclines to condemn the whole business beforehand as an impossible fable. I fancy Mr. SOMERSET MAUGHAM felt something of this difficulty with regard to the protagonist of his quaintly-called The Moon and Sixpence (HEINEMANN), since, for all his sly pretence of quoting imaginary authorities, we have really only his unsupported word for the superlative genius of Charles Strickland, the stockbroker who abandoned respectable London to become a Post-impressionist master, a vagabond and ultimately a Pacific Islander. The more credit then to Mr. MAUGHAM that he does quite definitely make us accept the fellow at his valuation. He owes this, perhaps, to the unsparing realism of the portrait. Heartless, utterly egotistical, without conscience or scruple or a single redeeming feature beyond the one consuming purpose of his art, Strickland is alive as few figures in recent fiction have been; a genuinely great though repellent personality—a man whom it would have been at once an event to have met and a pleasure to have kicked. Mr. MAUGHAM has certainly done nothing better than this book about him; the drily sardonic humour of his method makes the picture not only credible but compelling. I liked especially the characteristic touch that shows Strickland escaping, not so much from the dull routine of stockbroking (genius has done that often enough in stories before now) as from the pseudo-artistic atmosphere of a flat in Westminster and a wife who collected blue china and mild celebrities. Mrs. Strickland indeed is among the best of the slighter characters in a tale with a singularly small cast; though it is, of course, by the central figure that it stands or falls. My own verdict is an unhesitating stet.

If there be any who still cherish a pleasant memory of the Bonnie Prince CHARLIE of the Jacobite legend, Miss MARJORIE BOWEN'S Mr. Misfortunate (COLLINS) will dispose of it. She gives us a study of the YOUNG PRETENDER in the decade following Culloden. Figures such as LOCHIEL, KEITH, GORING, the dour KELLY, HENRY STUART, LOUIS XV., with sundry courtiers and mistresses, move across the film. I should say the author's sympathy is with her main subject, but her conscience is too much for her. I find myself increasingly exercised over this conscience of Miss BOWEN'S. She seems to me to be deliberately committing herself to what I can only describe as a staccato method. This was notably the case with The Burning Glass, her last novel. Her narratives no longer seem to flow. She will give you catalogues of furniture and raiment, with short scenes interspersed, for all the world as if she were transcribing from carefully taken notes. Quite probably she is, and I am being authentically instructed and should be duly grateful, but I find myself longing for the exuberance of her earlier method. I feel quite sure this competent author can find a way of respecting historical truth without killing the full-blooded flavour of romance.

There is a smack of the Early Besantine about the earnest [pg 372] scion of a noble house who decides to share the lives and lot of common and unwashed men with an eye to the imminent appearance of the True Spirit of Democracy in our midst. Such a one is the hero of Miss MAUD DIVER'S latest novel, Strange Roads (CONSTABLE); but it is only fair to say that Derek Blunt (né Blount), second son of the Earl of Avonleigh, is no prig, but, on the contrary, a very pleasant fellow. For a protagonist he obtrudes himself only moderately in a rather discursive story which involves a number of other people who do nothing in particular over a good many chapters. We are halfway through before Derek takes the plunge, and then we find, him, not in the slums of some industrial quarter, but in Western Canada, where class distinctions are founded less on soap than on simoleons. At the end of the volume the War has "bruk out," and our hero, apart from having led a healthy outdoor life and chivalrously married and been left a widower by a pathetic child with consumption and no morals, is just about where he started. I say "at the end of the volume," for there I find a publisher's note to the effect that in consequence of the paper shortage the further adventures of our hero have been postponed to a subsequent volume. It is to be entitled The Strong Hours, and will doubtless provide a satisfactory raison d'être for all the other people who did nothing in particular in Vol. I.

If you had numbered Elizabeth, the heroine of A Maiden in Malaya (MELROSE), among your friends, I can fancy your calling upon her to "hear about her adventures in the East." I can see her delightedly telling you of the voyage, of the people she met on board (including the charming young man upon whom you would already have congratulated her), of how he and she bought curios at Port Said, of her arrival, of her sister's children and their quaint sayings, of Singapore and its sights, of Malaya and how she was taken to see the tapping on a rubber plantation—here I picture a gleam of revived interest, possibly financial in origin, appearing in your face—of the club, of dinner parties and a thousand other details, all highly entertaining to herself and involving a sufficiency of native words to impress the stay-at-home. And perhaps, just as you were considering your chance of an escape before tea, she would continue "and now I must tell you all about the dreadful time I had in the rising!" which she would then vivaciously proceed to do; and not only that, but all about the dreadful time (the same dreadful time) that all her friends had in the same rising, chapters of it, so that in the end it might be six o'clock or later before you got away. I hope this is not an unfair résumé of the impression produced upon me by Miss ISOBEL MOUNTAIN'S prattling pages. To sum up, if you have an insatiable curiosity for the small talk of other people's travel, A Maiden in Malaya may not prove too much for it. If otherwise, otherwise.

I wish Col. JOHN BUCHAN could have been jogging Mrs. A.C. INCHBOLD'S elbow while she was writing Love and the Crescent (HUTCHINSON), All the essential people in his Greenmantle, which deals, towards the end at any rate, with just about the same scenes and circumstances as her story, are so confoundedly efficient, have so undeniably learnt the trick of making the most of their dashing opportunities. In Mrs. INCHBOLD's book the trouble is that with much greater advantages in the way of local knowledge and with all manner of excitement, founded on fact, going a-begging, nothing really thrilling or convincing ever quite materialises. The heroine, Armenian and beautiful, is as ineffective as the hero, who is French and heroic, both of them displaying the same unfortunate tendency to be carried off captive by the other side and to indulge in small talk when they should be most splendid. And the majority of the other figures follow suit. On the face of it the volume is stuffed with all the material of melodrama; but somehow the authoress seems to strive after effects that don't come naturally to her. What does come naturally to her is seen in a background sketch of the unhappy countries of Asia Minor in the hands of the Turk and the Hun, which is so much the abler part of the book that one would almost rather the too intrusive narrative were brushed aside entirely. Personally, at any rate, I think I should prefer Mrs. INCHBOLD in essay or historical form.

Madame ALBANESI, in Tony's Wife (HOLDEN AND HARDINGHAM), has provided her admirers with a goodly collection of sound Albanesians, but she has also given them a villain in whom, I cannot help thinking, they will find themselves hard-pressed to believe. Richard Savile was deprived of a great inheritance by Tony's birth, and as his guardian spent long years in nourishing revenge. He was not, we know, the first guardian to play this game, but that he could completely deceive so many people for such a long time seems to prove him far cleverer than appears from any actual evidence furnished. If, however, this portrait is not in the artist's best manner, I can praise without reserve the picture of Lady Féo, a little Society butterfly, very frivolous on the surface, but concealing a lot of nice intuition and sympathy, and I welcome her as a set-off to the silly caricatures we commonly get of the class to which she belonged. Let me add that in the telling of this tale Madame ALBANESI retains her quiet and individual charm.

A Curious Romanian Custom.

"The two white doves which were perched in the wedding carriage excited much interest. They were given, following the pretty Roumanian cuckoo, to the bride and bridegroom by the people of Roumania to symbolise the happiness and peace which are hoped to the newly-married couple."—North Mail.

"A ROMANTIC COURTSHIP IN TURKEY.

Miss —— visited Colonel —— when boat, money, a hiding-place in Constantinople last summer suffering from smallpox."—Provincial Paper.