This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Grizzly King

Author: James Oliver Curwood

Release Date: February 7, 2004 [eBook #10977]

Language: English

Character set encoding: iso-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE GRIZZLY KING***

It is with something like a confession that I offer this second of my nature books to the public—a confession, and a hope; the confession of one who for years hunted and killed before he learned that the wild offered a more thrilling sport than slaughter—and the hope that what I have written may make others feel and understand that the greatest thrill of the hunt is not in killing, but in letting live. It is true that in the great open spaces one must kill to live; one must have meat, and meat is life. But killing for food is not the lust of slaughter; it is not the lust which always recalls to me that day in the British Columbia mountains when, in less than two hours, I killed four grizzlies on a mountain slide—a destruction of possibly a hundred and twenty years of life in a hundred and twenty minutes. And that is only one instance of many in which I now regard myself as having been almost a criminal—for killing for the excitement of killing can be little less than murder. In their small way my animal books are the reparation I am now striving to make, and it has been my earnest desire to make them not only of romantic interest, but reliable in their fact. As in human life, there are tragedy, and humour, and pathos in the life of the wild; there are facts of tremendous interest, real happenings and real lives to be written about, and very small necessity for one to draw on imagination. In "Kazan" I tried to give the reader a picture of my years of experience among the wild sledge dogs of the North. In "The Grizzly" I have scrupulously adhered to facts as I have found them in the lives of the wild creatures of which I have written. Little Muskwa was with me all that summer and autumn in the Canadian Rockies. Pipoonaskoos is buried in the Firepan Range country, with a slab over his head, just like a white man. The two grizzly cubs we dug out on the Athabasca are dead. And Thor still lives, for his range is in a country where no hunters go—and when at last the opportunity came we did not kill him. This year (in July of 1916) I am going back into the country of Thor and Muskwa. I think I would know Thor if I saw him again, for he was a monster full-grown. But in two years Muskwa had grown from cubhood into full bearhood. And yet I believe that Muskwa would know me should we chance to meet again. I like to think that he has not forgotten the sugar, and the scores of times he cuddled up close to me at night, and the hunts we had together after roots and berries, and the sham fights with which we amused ourselves so often in camp. But, after all, perhaps he would not forgive me for that last day when we ran away from him so hard—leaving him alone to his freedom in the mountains.

JAMES OLIVER CURWOOD.

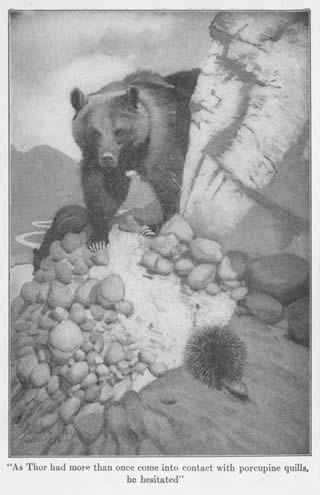

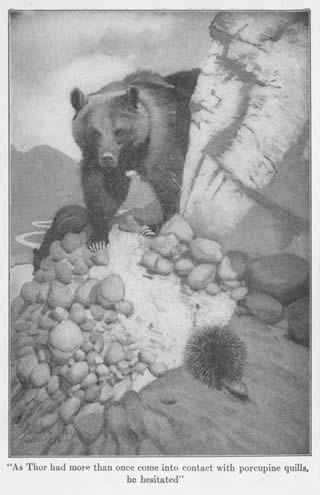

"As Thor had more than once come into contact with porcupine quills, he hesitated."

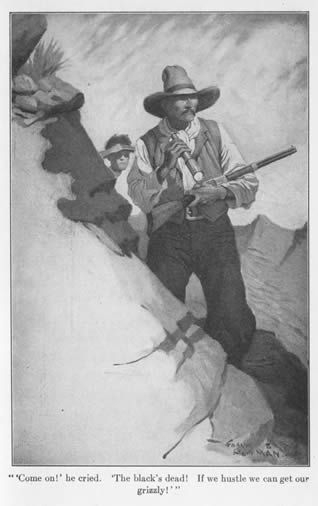

"'Come on!' he cried. 'The black's dead! If we hustle we can get our grizzly!'"

With the silence and immobility of a great reddish-tinted rock, Thor stood for many minutes looking out over his domain. He could not see far, for, like all grizzlies, his eyes were small and far apart, and his vision was bad. At a distance of a third or a half a mile he could make out a goat or a mountain sheep, but beyond that his world was a vast sun-filled or night-darkened mystery through which he ranged mostly by the guidance of sound and smell.

It was the sense of smell that held him still and motionless now. Up out of the valley a scent had come to his nostrils that he had never smelled before. It was something that did not belong there, and it stirred him strangely. Vainly his slow-working brute mind struggled to comprehend it. It was not caribou, for he had killed many caribou; it was not goat; it was not sheep; and it was not the smell of the fat and lazy whistlers sunning themselves on the rocks, for he had eaten hundreds of whistlers. It was a scent that did not enrage him, and neither did it frighten him. He was curious, and yet he did not go down to seek it out. Caution held him back.

If Thor could have seen distinctly for a mile, or two miles, his eyes would have discovered even less than the wind brought to him from down the valley. He stood at the edge of a little plain, with the valley an eighth of a mile below him, and the break over which he had come that afternoon an eighth of a mile above him. The plain was very much like a cup, perhaps an acre in extent, in the green slope of the mountain. It was covered with rich, soft grass and June flowers, mountain violets and patches of forget-me-nots, and wild asters and hyacinths, and in the centre of it was a fifty-foot spatter of soft mud which Thor visited frequently when his feet became rock-sore.

To the east and the west and the north of him spread out the wonderful panorama of the Canadian Rockies, softened in the golden sunshine of a June afternoon.

From up and down the valley, from the breaks between the peaks, and from the little gullies cleft in shale and rock that crept up to the snow-lines came a soft and droning murmur. It was the music of running water. That music was always in the air, for the rivers, the creeks, and the tiny streams gushing down from the snow that lay eternally up near the clouds were never still.

There were sweet perfumes as well as music in the air. June and July—the last of spring and the first of summer in the northern mountains—were commingling. The earth was bursting with green; the early flowers were turning the sunny slopes into coloured splashes of red and white and purple, and everything that had life was singing—the fat whistlers on their rocks, the pompous little gophers on their mounds, the big bumblebees that buzzed from flower to flower, the hawks in the valley, and the eagles over the peaks. Even Thor was singing in his way, for as he had paddled through the soft mud a few minutes before he had rumbled curiously deep down in his great chest. It was not a growl or a roar or a snarl; it was the noise he made when he was contented. It was his song.

And now, for some mysterious reason, there had suddenly come a change in this wonderful day for him. Motionless he still sniffed the wind. It puzzled him. It disquieted him without alarming him. To the new and strange smell that was in the air he was as keenly sensitive as a child's tongue to the first sharp touch of a drop of brandy. And then, at last, a low and sullen growl came like a distant roll of thunder from out of his chest. He was overlord of these domains, and slowly his brain told him that there should be no smell which he could not comprehend, and of which he was not the master.

Thor reared up slowly, until the whole nine feet of him rested on his haunches, and he sat like a trained dog, with his great forefeet, heavy with mud, drooping in front of his chest. For ten years he had lived in these mountains and never had he smelled that smell. He defied it. He waited for it, while it came stronger and nearer. He did not hide himself. Clean-cut and unafraid, he stood up.

He was a monster in size, and his new June coat shone a golden brown in the sun. His forearms were almost as large as a man's body; the three largest of his five knifelike claws were five and a half inches long; in the mud his feet had left tracks that were fifteen inches from tip to tip. He was fat, and sleek, and powerful. His eyes, no larger than hickory nuts, were eight inches apart. His two upper fangs, sharp as stiletto points, were as long as a man's thumb, and between his great jaws he could crush the neck of a caribou.

Thor's life had been free of the presence of man, and he was not ugly. Like most grizzlies, he did not kill for the pleasure of killing. Out of a herd he would take one caribou, and he would eat that caribou to the marrow in the last bone. He was a peaceful king. He had one law: "Let me alone!" he said, and the voice of that law was in his attitude as he sat on his haunches sniffing the strange smell.

In his massive strength, in his aloneness and his supremacy, the great bear was like the mountains, unrivalled in the valleys as they were in the skies. With the mountains, he had come down out of the ages. He was part of them. The history of his race had begun and was dying among them, and they were alike in many ways. Until this day he could not remember when anything had come to question his might and his right—except those of his own kind. With such rivals he had fought fairly and more than once to the death. He was ready to fight again, if it came to a question of sovereignty over the ranges which he claimed as his own. Until he was beaten he was dominator, arbiter, and despot, if he chose to be. He was dynast of the rich valleys and the green slopes, and liege lord of all living things about him. He had won and kept these things openly, without strategy or treachery. He was hated and he was feared, but he was without hatred or fear of his own—and he was honest. Therefore he waited openly for the strange thing that was coming to him from down the valley.

As he sat on his haunches, questioning the air with his keen brown nose, something within him was reaching back into dim and bygone generations. Never before had he caught the taint that was in his nostrils, yet now that it came to him it did not seem altogether new. He could not place it. He could not picture it. Yet he knew that it was a menace and a threat.

For ten minutes he sat like a carven thing on his haunches. Then the wind shifted, and the scent grew less and less, until it was gone altogether.

Thor's flat ears lifted a little. He turned his huge head slowly so that his eyes took in the green slope and the tiny plain. He easily forgot the smell now that the air was clear and sweet again. He dropped on his four feet, and resumed his gopher-hunting.

There was something of humour in his hunt. Thor weighed a thousand pounds; a mountain gopher is six inches long and weighs six ounces. Yet Thor would dig energetically for an hour, and rejoice at the end by swallowing the fat little gopher like a pill; it was his bonne bouche, the luscious tidbit in the quest of which he spent a third of his spring and summer digging.

He found a hole located to his satisfaction and began throwing out the earth like a huge dog after a rat. He was on the crest of the slope. Once or twice during the next half-hour he lifted his head, but he was no longer disturbed by the strange smell that had come to him with the wind.

A mile down the valley Jim Langdon stopped his horse where the spruce and balsam timber thinned out at the mouth of a coulee, looked ahead of him for a breathless moment or two, and then with an audible gasp of pleasure swung his right leg over so that his knee crooked restfully about the horn of his saddle, and waited.

Two or three hundred yards behind him, still buried in the timber, Otto was having trouble with Dishpan, a contumacious pack-mare. Langdon grinned happily as he listened to the other's vociferations, which threatened Dishpan with every known form of torture and punishment, from instant disembowelment to the more merciful end of losing her brain through the medium of a club. He grinned because Otto's vocabulary descriptive of terrible things always impending over the heads of his sleek and utterly heedless pack-horses was one of his chief joys. He knew that if Dishpan should elect to turn somersaults while diamond-hitched under her pack, big, good-natured Bruce Otto would do nothing more than make the welkin ring with his terrible, blood-curdling protest.

One after another the six horses of their outfit appeared out of the timber, and last of all rode the mountain man. He was gathered like a partly released spring in his saddle, an attitude born of years in the mountains, and because of a certain difficulty he had in distributing gracefully his six-foot-two-inch length of flesh and bone astride a mountain cayuse.

Upon his appearance Langdon dismounted, and turned his eyes again up the valley. The stubbly blond beard on his face did not conceal the deep tan painted there by weeks of exposure in the mountains; he had opened his shirt at the throat, exposing a neck darkened by sun and wind; his eyes were of a keen, searching blue-gray, and they quested the country ahead of him now with the joyous intentness of the hunter and the adventurer.

Langdon was thirty-five. A part of his life he spent in the wild places; the other part he spent in writing about the things he found there. His companion was five years his junior in age, but had the better of him by six inches in length of anatomy, if those additional inches could be called an advantage. Bruce thought they were not. "The devil of it is I ain't done growin' yet!" he often explained.

He rode up now and unlimbered himself. Langdon pointed ahead.

"Did you ever see anything to beat that?" he asked.

"Fine country," agreed Bruce. "Mighty good place to camp, too, Jim. There ought to be caribou in this range, an' bear. We need some fresh meat. Gimme a match, will you?"

It had come to be a habit with them to light both their pipes with one match when possible. They performed this ceremony now while viewing the situation. As he puffed the first luxurious cloud of smoke from his bulldog, Langdon nodded toward the timber from which they had just come.

"Fine place for our tepee," he said. "Dry wood, running water, and the first good balsam we've struck in a week for our beds. We can hobble the horses in that little open plain we crossed a quarter of a mile back. I saw plenty of buffalo grass and a lot of wild timothy."

He looked at his watch.

"It's only three o'clock. We might go on. But—what do you say? Shall we stick for a day or two, and see what this country looks like?"

"Looks good to me," said Bruce.

He sat down as he spoke, with his back to a rock, and over his knee he levelled a long brass telescope. From his saddle Langdon unslung a binocular glass imported from Paris. The telescope was a relic of the Civil War. Together, their shoulders touching as they steadied themselves against the rock, they studied the rolling slopes and the green sides of the mountains ahead of them.

They were in the Big Game country, and what Langdon called the Unknown. So far as he and Bruce Otto could discover, no other white man had ever preceded them. It was a country shut in by tremendous ranges, through which it had taken them twenty days of sweating toil to make a hundred miles.

That afternoon they had crossed the summit of the Great Divide that split the skies north and south, and through their glasses they were looking now upon the first green slopes and wonderful peaks of the Firepan Mountains. To the northward—and they had been travelling north—was the Skeena River; on the west and south were the Babine range and waterways; eastward, over the Divide, was the Driftwood, and still farther eastward the Ominica range and the tributaries of the Finley. They had started from civilization on the tenth day of May and this was the thirtieth of June.

As Langdon looked through his glasses he believed that at last they had reached the bourne of their desires. For nearly two months they had worked to get beyond the trails of men, and they had succeeded. There were no hunters here. There were no prospectors. The valley ahead of them was filled with golden promise, and as he sought out the first of its mystery and its wonder his heart was filled with the deep and satisfying joy which only men like Langdon can fully understand. To his friend and comrade, Bruce Otto, with whom he had gone five times into the North country, all mountains and all valleys were very much alike; he was born among them, he had lived among them all his life, and he would probably die among them.

It was Bruce who gave him a sudden sharp nudge with his elbow.

"I see the heads of three caribou crossing a dip about a mile and a half up the valley," he said, without taking his eyes from the telescope.

"And I see a Nanny and her kid on the black shale of that first mountain to the right," replied Langdon. "And, by George, there's a Sky Pilot looking down on her from a crag a thousand feet above the shale! He's got a beard a foot long. Bruce, I'll bet we've struck a regular Garden of Eden!"

"Looks it," vouchsafed Bruce, coiling up his long legs to get a better rest for his telescope. "If this ain't a sheep an' bear country, I've made the worst guess I ever made in my life."

For five minutes they looked, without a word passing between them. Behind them their horses were nibbling hungrily in the thick, rich grass. The sound of the many waters in the mountains droned in their ears, and the valley seemed sleeping in a sea of sunshine. Langdon could think of nothing more comparable than that—slumber. The valley was like a great, comfortable, happy cat, and the sounds they heard, all commingling in that pleasing drone, was its drowsy purring. He was focussing his glass a little more closely on the goat standing watchfully on its crag, when Otto spoke again.

"I see a grizzly as big as a house!" he announced quietly.

Bruce seldom allowed his equanimity to be disturbed, except by the pack-horses. Thrilling news like this he always introduced as unconcernedly as though speaking of a bunch of violets.

Langdon sat up with a jerk.

"Where?" he demanded.

He leaned over to get the range of the other's telescope, every nerve in his body suddenly aquiver.

"See that slope on the second shoulder, just beyond the ravine over there?" said Bruce, with one eye closed and the other still glued to the telescope. "He's halfway up, digging out a gopher."

Langdon focussed his glass on the slope, and a moment later an excited gasp came from him.

"See 'im?" asked Bruce.

"The glass has pulled him within four feet of my nose," replied Langdon. "Bruce, that's the biggest grizzly in the Rocky Mountains!"

"If he ain't, he's his twin brother," chuckled the packer, without moving a muscle. "He beats your eight-footer by a dozen inches, Jimmy! An'"—he paused at this psychological moment to pull a plug of black MacDonald from his pocket and bite off a mouthful, without taking the telescope from his eye—"an' the wind is in our favour an' he's as busy as a flea!" he finished.

Otto unwound himself and rose to his feet, and Langdon jumped up briskly. In such situations as this there was a mutual understanding between them which made words unnecessary. They led the eight horses back into the edge of the timber and tied them there, took their rifles from the leather holsters, and each was careful to put a sixth cartridge in the chamber of his weapon. Then for a matter of two minutes they both studied the slope and its approaches with their naked eyes.

"We can slip up the ravine," suggested Langdon.

Bruce nodded.

"I reckon it's a three-hundred-yard shot from there," he said. "It's the best we can do. He'd get our wind if we went below 'im. If it was a couple o' hours earlier—"

"We'd climb over the mountain and come down on him from above!" exclaimed Langdon, laughing.

"Bruce, you're the most senseless idiot on the face of the globe when it comes to climbing mountains! You'd climb over Hardesty or Geikie to shoot a goat from above, even though you could get him from the valley without any work at all. I'm glad it isn't morning. We can get that bear from the ravine!"

"Mebbe," said Bruce, and they started.

They walked openly over the green, flower-carpeted meadows ahead of them. Until they came within at least half a mile of the grizzly there was no danger of him seeing them. The wind had shifted, and was almost in their faces. Their swift walk changed to a dog-trot, and they swung in nearer to the slope, so that for fifteen minutes a huge knoll concealed the grizzly. In another ten minutes they came to the ravine, a narrow, rock-littered and precipitous gully worn in the mountainside by centuries of spring floods gushing down from the snow-peaks above. Here they made cautious observation.

The big grizzly was perhaps six hundred yards up the slope, and pretty close to three hundred yards from the nearest point reached by the gully.

Bruce spoke in a whisper now.

"You go up an' do the stalkin', Jimmy," he said. "That bear's goin' to do one of two things if you miss or only wound 'im—one o' three, mebbe: he's going to investigate you, or he's going up over the break, or he's comin' down in the valley—this way. We can't keep 'im from goin' over the break, an' if he tackles you—just summerset it down the gully. You can beat 'im out. He's most apt to come this way if you don't get 'im, so I'll wait here. Good luck to you, Jimmy!"

With this he went out and crouched behind a rock, where he could keep an eye on the grizzly, and Langdon began to climb quietly up the boulder-strewn gully.

Of all the living creatures in this sleeping valley, Thor was the busiest. He was a bear with individuality, you might say. Like some people, he went to bed very early; he began to get sleepy in October, and turned in for his long nap in November. He slept until April, and usually was a week or ten days behind other bears in waking. He was a sound sleeper, and when awake he was very wide awake. During April and May he permitted himself to doze considerably in the warmth of sunny rocks, but from the beginning of June until the middle of September he closed his eyes in real sleep just about four hours out of every twelve.

He was very busy as Langdon began his cautious climb up the gully. He had succeeded in getting his gopher, a fat, aldermanic old patriarch who had disappeared in one crunch and a gulp, and he was now absorbed in finishing off his day's feast with an occasional fat, white grub and a few sour ants captured from under stones which he turned over with his paw.

In his search after these delicacies Thor used his right paw in turning over the rocks. Ninety-nine out of every hundred bears—probably a hundred and ninety-nine out of every two hundred—are left-handed; Thor was right-handed. This gave him an advantage in fighting, in fishing, and in stalking meat, for a grizzly's right arm is longer than his left—so much longer that if he lost his sixth sense of orientation he would be constantly travelling in a circle.

In his quest Thor was headed for the gully. His huge head hung close to the ground. At short distances his vision was microscopic in its keenness; his olfactory nerves were so sensitive that he could catch one of the big rock-ants with his eyes shut.

He would choose the flat rocks mostly. His huge right paw, with its long claws, was as clever as a human hand. The stone lifted, a sniff or two, a lick of his hot, flat tongue, and he ambled on to the next.

He took this work with tremendous seriousness, much like an elephant hunting for peanuts hidden in a bale of hay. He saw no humour in the operation. As a matter of fact, Nature had not intended there should be any humour about it. Thor's time was more or less valueless, and during the course of a summer he absorbed in his system a good many hundred thousand sour ants, sweet grubs, and juicy insects of various kinds, not to mention a host of gophers and still tinier rock-rabbits. These small things all added to the huge rolls of fat which it was necessary for him to store up for that "absorptive consumption" which kept him alive during his long winter sleep. This was why Nature had made his little greenish-brown eyes twin microscopes, infallible at distances of a few feet, and almost worthless at a thousand yards.

As he was about to turn over a fresh stone Thor paused in his operations. For a full minute he stood nearly motionless. Then his head swung slowly, his nose close to the ground. Very faintly he had caught an exceedingly pleasing odour. It was so faint that he was afraid of losing it if he moved. So he stood until he was sure of himself, then he swung his huge shoulders around and descended two yards down the slope, swinging his head slowly from right to left, and sniffing. The scent grew stronger. Another two yards down the slope he found it very strong under a rock. It was a big rock, and weighed probably two hundred pounds. Thor dragged it aside with his one right hand as if it were no more than a pebble.

Instantly there was a wild and protesting chatter, and a tiny striped rock-rabbit, very much like a chipmunk, darted away just as Thor's left hand came down with a smash that would have broken the neck of a caribou.

It was not the scent of the rock-rabbit, but the savour of what the rock-rabbit had stored under the stone that had attracted Thor. And this booty still remained—a half-pint of ground-nuts piled carefully in a little hollow lined with moss. They were not really nuts. They were more like diminutive potatoes, about the size of cherries, and very much like potatoes in appearance. They were starchy and sweet, and fattening. Thor enjoyed them immensely, rumbling in that curious satisfied way deep down in his chest as he feasted. And then he resumed his quest.

He did not hear Langdon as the hunter came nearer and nearer up the broken gully. He did not smell him, for the wind was fatally wrong. He had forgotten the noxious man-smell that had disturbed and irritated him an hour before. He was quite happy; he was good-humoured; he was fat and sleek. An irritable, cross-grained, and quarrelsome bear is always thin. The true hunter knows him as soon as he sets eyes on him. He is like the rogue elephant.

Thor continued his food-seeking, edging still closer to the gully. He was within a hundred and fifty yards of it when a sound suddenly brought him alert. Langdon, in his effort to creep up the steep side of the gully for a shot, had accidentally loosened a rock. It went crashing down the ravine, starting other stones that followed in a noisy clatter. At the foot of the coulee, six hundred yards down, Bruce swore softly under his breath. He saw Thor sit up. At that distance he was going to shoot if the bear made for the break.

For thirty seconds Thor sat on his haunches. Then he started for the ravine, ambling slowly and deliberately. Langdon, panting and inwardly cursing at his ill luck, struggled to make the last ten feet to the edge of the slope. He heard Bruce yell, but he could not make out the warning. Hands and feet he dug fiercely into shale and rock as he fought to make those last three or four yards as quickly as possible.

He was almost to the top when he paused for a moment and turned his eyes upward. His heart went into his throat, and he started. For ten seconds he could not move. Directly over him was a monster head and a huge hulk of shoulder. Thor was looking down on him, his jaws agape, his finger-long fangs snarling, his eyes burning with a greenish-red fire.

In that moment Thor saw his first of man. His great lungs were filled with the hot smell of him, and suddenly he turned away from that smell as if from a plague. With his rifle half under him Langdon had had no opportunity to shoot. Wildly he clambered up the remaining few feet. The shale and stones slipped and slid under him. It was a matter of sixty seconds before he pulled himself over the top.

Thor was a hundred yards away, speeding in a rolling, ball-like motion toward the break. From the foot of the coulee came the sharp crack of Otto's rifle. Langdon squatted quickly, raising his left knee for a rest, and at a hundred and fifty yards began firing.

Sometimes it happens that an hour—a minute—changes the destiny of man; and the ten seconds which followed swiftly after that first shot from the foot of the coulee changed Thor. He had got his fill of the man-smell. He had seen man. And now he felt him.

It was as if one of the lightning flashes he had often seen splitting the dark skies had descended upon him and had entered his flesh like a red-hot knife; and with that first burning agony of pain came the strange, echoing roar of the rifles. He had turned up the slope when the bullet struck him in the fore-shoulder, mushrooming its deadly soft point against his tough hide, and tearing a hole through his flesh—but without touching the bone. He was two hundred yards from the ravine when it hit; he was nearer three hundred when the stinging fire seared him again, this time in his flank.

Neither shot had staggered his huge bulk, twenty such shots would not have killed him. But the second stopped him, and he turned with a roar of rage that was like the bellowing of a mad bull—a snarling, thunderous cry of wrath that could have been heard a quarter of a mile down the valley.

Bruce heard it as he fired his sixth unavailing shot at seven hundred yards. Langdon was reloading. For fifteen seconds Thor offered himself openly, roaring his defiance, challenging the enemy he could no longer see; and then at Langdon's seventh shot, a whiplash of fire raked his back, and in strange dread of this lightning which he could not fight, Thor continued up over the break. He heard other rifle shots, which were like a new kind of thunder. But he was not hit again. Painfully he began the descent into the next valley.

Thor knew that he was hurt, but he could not comprehend that hurt. Once in the descent he paused for a few moments, and a little pool of blood dripped upon the ground under his foreleg. He sniffed at it suspiciously and wonderingly.

He swung eastward, and a little later he caught a fresh taint of the man-smell in the air. The wind was bringing it to him now, and in spite of the fact that he wanted to lie down and nurse his wound he ambled on a little faster, for he had learned one thing that he would never forget: the man-smell and his hurt had come together.

He reached the bottoms, and buried himself in the thick timber; and then, crossing this timber, he came to a creek. Perhaps a hundred times he had travelled up and down this creek. It was the main trail that led from one half of his range to the other.

Instinctively he always took this trail when he was hurt or when he was sick, and also when he was ready to den up for the winter. There was one chief reason for this: he was born in the almost impenetrable fastnesses at the head of the creek, and his cubhood had been spent amid its brambles of wild currants and soap berries and its rich red ground carpets of kinnikinic. It was home. In it he was alone. It was the one part of his domain that he held inviolate from all other bears. He tolerated other bears—blacks and grizzlies—on the wider and sunnier slopes of his range just so long as they moved on when he approached. They might seek food there, and nap in the sun-pools, and live in quiet and peace if they did not defy his suzerainty.

Thor did not drive other bears from his range, except when it was necessary to demonstrate again that he was High Mogul. This happened occasionally, and there was a fight. And always after a fight Thor came into this valley and went up the creek to cure his wounds.

He made his way more slowly than usual to-day. There was a terrible pain in his fore-shoulder. Now and then it hurt him so that his leg doubled up, and he stumbled. Several times he waded shoulder-deep into pools and let the cold water run over his wounds. Gradually they stopped bleeding. But the pain grew worse.

Thor's best friend in such an emergency was a clay wallow. This was the second reason why he always took this trail when he was sick or hurt. It led to the clay wallow. And the clay wallow was his doctor.

The sun was setting before he reached the wallow. His jaws hung open a little. His great head drooped lower. He had lost a great deal of blood. He was tired, and his shoulder hurt him so badly that he wanted to tear with his teeth at the strange fire that was consuming it.

The clay wallow was twenty or thirty feet in diameter, and hollowed into a little shallow pool in the centre. It was a soft, cool, golden-coloured clay, and Thor waded into it to his armpits. Then he rolled over gently on his wounded side. The clay touched his hurt like a cooling salve. It sealed the cut, and Thor gave a great heaving gasp of relief. For a long time he lay in that soft bed of clay. The sun went down, darkness came, and the wonderful stars filled the sky. And still Thor lay there, nursing that first hurt of man.

In the edge of the balsam and spruce Langdon and Otto sat smoking their pipes after supper, with the glowing embers of a fire at their feet. The night air in these higher altitudes of the mountains had grown chilly, and Bruce rose long enough to throw a fresh armful of dry spruce on the coals. Then he stretched out his long form again, with his head and shoulders bolstered comfortably against the butt of a tree, and for the fiftieth time he chuckled.

"Chuckle an' be blasted," growled Langdon. "I tell you I hit him twice, Bruce—twice anyway; and I was at a devilish disadvantage!"

"'Specially when 'e was lookin' down an' grinnin' in your face," retorted Bruce, who had enjoyed hugely his comrade's ill luck. "Jimmy, at that distance you should a'most ha' killed 'im with a rock!"

"My gun was under me," explained Langdon for the twentieth time.

"W'ich ain't just the proper place for a gun to be when yo'r hunting a grizzly," reminded Bruce.

"The gully was confoundedly steep. I had to dig in with both feet and my fingers. If it had been any steeper I would have used my teeth."

Langdon sat up, knocked the ash out of the bowl of his pipe, and reloaded it with fresh tobacco.

"Bruce, that's the biggest grizzly in the Rocky Mountains!"

"He'd 'a' made a fine rug in your den, Jimmy—if yo'r gun hadn't 'appened to 'ave been under you."

"And I'm going to have him in my den before I finish," declared Langdon. "I've made up my mind. We'll make a permanent camp here. I'm going to get that grizzly if it takes all summer. I'd rather have him than any other ten bears in the Firepan Range. He was a nine-footer if an inch. His head was as big as a bushel basket, and the hair on his shoulders was four inches long. I don't know that I'm sorry I didn't kill him. He's hit, and he'll surely fight say. There'll be a lot of fun in getting him."

"There will that," agreed Bruce, "'specially if you meet 'im again during the next week or so, while he's still sore from the bullets. Better not have the gun under you then, Jimmy!"

"What do you say to making this a permanent camp?"

"Couldn't be better. Plenty of fresh meat, good grazing, and fine water." After a moment he added: "He was hit pretty hard. He was bleedin' bad at the summit."

In the firelight Langdon began cleaning his rifle.

"You think he may clear out—leave the country?"

Bruce emitted a grunt of disgust.

"Clear out? Run away? Mebbe he would if he was a black. But he's a grizzly, and the boss of this country. He may fight shy of this valley for a while, but you can bet he ain't goin' to emigrate. The harder you hit a grizzly the madder he gets, an' if you keep on hittin' 'im he keeps on gettin' madder, until he drops dead. If you want that bear bad enough we can surely get him."

"I do," Langdon reiterated with emphasis. "He'll smash record measurements or I miss my guess. I want him, and I want him bad, Bruce. Do you think we'll be able to trail him in the morning?"

Bruce shook his head.

"It won't be a matter of trailing," he said. "It's just simply hunt. After a grizzly has been hit he keeps movin'. He won't go out of his range, an' neither is he going to show himself on the open slopes like that up there. Metoosin ought to be along with the dogs inside of three or four days, an' when we get that bunch of Airedales in action, there'll be some fun."

Langdon sighted at the fire through the polished barrel of his rifle, and said doubtfully:

"I've been having my doubts about Metoosin for a week back. We've come through some mighty rough country."

"That old Indian could follow our trail if we travelled on rock," declared Bruce confidently. "He'll be here inside o' three days, barring the dogs don't run their fool heads into too many porcupines. An' when they come"—he rose and stretched his gaunt frame—"we'll have the biggest time we ever had in our lives. I'm just guessin' these mount'ins are so full o' bear that them ten dogs will all be massacreed within a week. Want to bet?"

Langdon closed his rifle with a snap.

"I only want one bear," he said, ignoring the challenge, "and I have an idea we'll get him to-morrow. You're the bear specialist of the outfit, Bruce, but I think he was too hard hit to travel far."

They had made two beds of soft balsam boughs near the fire, and Langdon now followed his companion's example, and began spreading his blankets. It had been a hard day, and within five minutes after stretching himself out he was asleep.

He was still asleep when Bruce rolled out from under his blanket at dawn. Without rousing Langdon the young packer slipped on his boots and waded back a quarter of a mile through the heavy dew to round up the horses. When he returned he brought Dishpan and their saddle-horses with him. By that time Langdon was up, and starting a fire.

Langdon frequently reminded himself that such mornings as this had made him disappoint the doctors and rob the grave. Just eight years ago this June he had come into the North for the first time, thin-chested and with a bad lung. "You can go if you insist, young man," one of the doctors had told him, "but you're going to your own funeral." And now he had a five-inch expansion and was as tough as a knot. The first rose-tints of the sun were creeping over the mountain-tops; the air was filled with the sweetness of flowers, and dew, and growing things, and his lungs drew in deep breaths of oxygen laden with the tonic and perfume of balsam.

He was more demonstrative than his companion in the joyousness of this wild life. It made him want to shout, and sing, and whistle. He restrained himself this morning. The thrill of the hunt was in his blood.

While Otto saddled the horses Langdon made the bannock. He had become an expert at what he called "wild-bread" baking, and his method possessed the double efficiency of saving both waste and time.

He opened one of the heavy canvas flour sacks, made a hollow in the flour with his two doubled fists, partly filled this hollow with a pint of water and half a cupful of caribou grease, added a tablespoonful of baking powder and a three-finger pinch of salt, and began to mix. Inside of five minutes he had the bannock loaves in the big tin reflector, and half an hour later the sheep steaks were fried, the potatoes done, and the bannock baked to a golden brown.

The sun was just showing its face in the east when they trailed out of camp. They rode across the valley, but walked up the slope, the horses following obediently in their footsteps.

It was not difficult to pick up Thor's trail. Where he had paused to snarl back defiance at his enemies there was a big red spatter on the ground; from this point to the summit they followed a crimson thread of blood. Three times in descending into the other valley they found where Thor had stopped, and each time they saw where a pool of blood had soaked into the earth or run over the rock.

They passed through the timber and came to the creek, and here, in a strip of firm black sand, Thor's footprints brought them to a pause. Bruce stared. An exclamation of amazement came from Langdon, and without a word having passed between them he drew out his pocket-tape and knelt beside one of the tracks.

"Fifteen and a quarter inches!" he gasped.

"Measure another," said Bruce.

"Fifteen and—a half!"

Bruce looked up the gorge.

"The biggest I ever see was fourteen an' a half," he said, and there was a touch of awe in his voice. "He was shot up the Athabasca an' he's stood as the biggest grizzly ever killed in British Columbia. Jimmy, this one beats 'im!"

They went on, and measured the tracks again at the edge of the first pool where Thor had bathed his wounds. There was almost no variation in the measurements. Only occasionally after this did they find spots of blood. It was ten o'clock when they came to the clay wallow and saw where Thor had made his bed in it.

"He was pretty sick," said Bruce in a low voice. "He was here most all night."

Moved by the same impulse and the same thought, they looked ahead of them. Half a mile farther on the mountains closed in until the gorge between them was dark and sunless.

"He was pretty sick," repeated Bruce, still looking ahead. "Mebbe we'd better tie the horses an' go on alone. It's possible—he's in there."

They tied the horses to scrub cedars, and relieved Dishpan of her pack.

Then, with their rifles in readiness, and eyes and ears alert, they went on cautiously into the silence and gloom of the gorge.

Thor had gone up the gorge at daybreak. He was stiff when he rose from the clay wallow, but a good deal of the burning and pain had gone from his wound. It still hurt him, but not as it had hurt him the preceding evening. His discomfort was not all in his shoulder, and it was not in any one place in particular. He was sick, and had he been human he would have been in bed with a thermometer under his tongue and a doctor holding his pulse. He walked up the gorge slowly and laggingly. An indefatigable seeker of food, he no longer thought of food. He was not hungry, and he did not want to eat.

With his hot tongue he lapped frequently at the cool water of the creek, and even more frequently he turned half about, and sniffed the wind. He knew that the man-smell and the strange thunder and the still more inexplicable lightning lay behind him. All night he had been on guard, and he was cautious now.

For a particular hurt Thor knew of no particular remedy. He was not a botanist in the finer sense of the word, but in creating him the Spirit of the Wild had ordained that he should be his own physician. As a cat seeks catnip, so Thor sought certain things when he was not feeling well. All bitterness is not quinine, but certainly bitter things were Thor's remedies, and as he made his way up the gorge his nose hung close to the ground, and he sniffed in the low copses and thick bush-tangles he passed.

He came to a small green spot covered with kinnikinic, a ground plant two inches high which bore red berries as big as a small pea. They were not red now, but green; bitter as gall, and contained an astringent tonic called uvaursi. Thor ate them.

After that he found soap berries growing on bushes that looked very much like currant bushes. The fruit was already larger than currants, and turning pink. Indians ate these berries when they had fever, and Thor gathered half a pint before he went on. They, too, were bitter.

He nosed the trees, and found at last what he wanted. It was a jackpine, and at several places within his reach the fresh pitch was oozing. A bear seldom passes a bleeding jackpine. It is his chief tonic, and Thor licked the fresh pitch with his tongue. In this way he absorbed not only turpentine, but also, in a roundabout sort of way, a whole pharmacopoeia of medicines made from this particular element.

By the time he arrived at the end of the gorge Thor's stomach was a fairly well-stocked drug emporium. Among other things he had eaten perhaps half a quart of spruce and balsam needles. When a dog is sick he eats grass; when a bear is sick he eats pine or balsam needles if he can get them. Also he pads his stomach and intestines with them in the last hour before denning himself away for the winter.

The sun was not yet up when Thor came to the end of the gorge, and stood for a few moments at the mouth of a low cave that reached back into the wall of the mountain. How far his memory went back it would be impossible to say; but in the whole world, as he knew it, this cave was home. It was not more than four feet high, and twice as wide, but it was many times as deep and was carpeted with a soft white floor of sand. In some past age a little stream had trickled out of this cavern, and the far end of it made a comfortable bedroom for a sleeping bear when the temperature was fifty degrees below zero.

Ten years before Thor's mother had gone in there to sleep through the winter, and when she waddled out to get her first glimpse of spring three little cubs waddled with her. Thor was one of them. He was still half blind, for it is five weeks after a grizzly cub is born before he can see; and there was not much hair on his body, for a grizzly cub is born as naked as a human baby. His eyes open and his hair begins to grow at just about the same time. Since then Thor had denned eight times in that cavern home.

He wanted to go in now. He wanted to lie down in the far end of it and wait until he felt better. For perhaps two or three minutes he hesitated, sniffing yearningly at the door to his cave, and then feeling the wind from down the gorge. Something told him that he should go on.

To the westward there was a sloping ascent up out of the gorge to the summit, and Thor climbed this. The sun was well up when he reached the top, and for a little while he rested again and looked down on the other half of his domain.

Even more wonderful was this valley than the one into which Bruce and Langdon had ridden a few hours before. From range to range it was a good two miles in width, and in the opposite directions it stretched away in a great rolling panorama of gold and green and black. From where Thor stood it was like an immense park. Green slopes reached almost to the summits of the mountains, and to a point halfway up these slopes—the last timber-line—clumps of spruce and balsam trees were scattered over the green as if set there by the hands of men. Some of these timber-patches were no larger than the decorative clumps in a city park, and others covered acres and tens of acres; and at the foot of the slopes on either side, like decorative fringes, were thin and unbroken lines of forest. Between these two lines of forest lay the open valley of soft and undulating meadow, dotted with its purplish bosks of buffalo willow and mountain sage, its green coppices of wild-rose and thorn, and its clumps of trees. In the hollow of the valley ran a stream.

Thor descended about four hundred yards from where he stood, and then turned northward along the green slope, so that he was travelling from patch to patch of the parklike timber, a hundred and fifty or two hundred yards above the fringe of forest. To this height, midway between the meadows in the valley and the first shale and bare rock of the peaks, he came most frequently on his small game hunts.

Like fat woodchucks the whistlers were already beginning to sun themselves on their rocks. Their long, soft, elusive whistlings, pleasant to hear above the drone of mountain waters, filled the air with a musical cadence. Now and then one would whistle shrilly and warningly close at hand, and then flatten himself out on his rock as the big bear passed, and for a few moments no whistling would break upon the gentle purring of the valley.

But Thor was giving no thought to the hunt this morning. Twice he encountered porcupines, the sweetest of all morsels to him, and passed them unnoticed; the warm, sleeping smell of a caribou came hot and fresh from a thicket, but he did not approach the thicket to investigate; out of a coulee, narrow and dark, like a black ditch, he caught the scent of a badger. For two hours he travelled steadily northward along the half-crest of the slopes before he struck down through the timber to the stream.

The clay adhering to his wound was beginning to harden, and again he waded shoulder-deep into a pool, and stood there for several minutes. The water washed most of the clay away. For another two hours he followed the creek, drinking frequently. Then came the sapoos oowin—six hours after he had left the clay wallow. The kinnikinic berries, the soap berries, the jackpine pitch, the spruce and balsam needles, and the water he had drunk, all mixed in his stomach in one big compelling dose, brought it about—and Thor felt tremendously better, so much better that for the first time he turned and growled back in the direction of his enemies. His shoulder still hurt him, but his sickness was gone.

For many minutes after the sapoos oowin he stood without moving, and many times he growled. The snarling rumble deep in his chest had a new meaning now. Until last night and to-day he had not known a real hatred. He had fought other bears, but the fighting rage was not hate. It came quickly, and passed away quickly; it left no growing ugliness; he licked the wounds of a clawed enemy, and was quite frequently happy while he nursed them. But this new thing that was born in him was different.

With an unforgetable and ferocious hatred he hated the thing that had hurt him. He hated the man-smell; he hated the strange, white-faced thing he had seen clinging to the side of the gorge; and his hatred included everything associated with them. It was a hatred born of instinct and roused sharply from its long slumber by experience.

Without ever having seen or smelled man before, he knew that man was his deadliest enemy, and to be feared more than all the wild things in the mountains. He would fight the biggest grizzly. He would turn on the fiercest pack of wolves. He would brave flood and fire without flinching. But before man he must flee! He must hide! He must constantly guard himself in the peaks and on the plains with eyes and ears and nose!

Why he sensed this, why he understood all at once that a creature had come into his world, a pigmy in size, yet more to be dreaded than any foe he had ever known, was a miracle which nature alone could explain. It was a hearkening back in the age-dimmed mental fabric of Thor's race to the earliest days of man—man, first of all, with the club; man with the spear hardened in fire; man with the flint-tipped arrow; man with the trap and the deadfall, and, lastly, man with the gun. Through all the ages man had been his one and only master. Nature had impressed it upon him—had been impressing it upon him through a hundred or a thousand or ten thousand generations.

And now for the first time in his life that dormant part of his instinct leaped into warning wakefulness, and he understood. He hated man, and hereafter he would hate everything that bore the man-smell. And with this hate there was also born in him for the first time fear. Had man never pushed Thor and his kind to the death the world would not have known him as Ursus Horribilis the Terrible.

Thor still followed the creek, nosing along slowly and lumberingly, but very steadily; his head and neck bent low, his huge rear quarters rising and falling in that rolling motion peculiar to all bears, and especially so of the grizzly. His long claws click-click-clicked on the stones; he crunched heavily in the gravel; in soft sand he left enormous footprints.

That part of the valley which he was now entering held a particular significance for Thor, and he began to loiter, pausing often to sniff the air on all sides of him. He was not a monogamist, but for many mating seasons past he had come to find his Iskwao in this wonderful sweep of meadow and plain between the two ranges. He could always expect her in July, waiting for him or seeking him with that strange savage longing of motherhood in her breast. She was a splendid grizzly who came from the western ranges when the spirit of mating days called; big, and strong, and of a beautiful golden-brown colour, so that the children of Thor and his Iskwao were the finest young grizzlies in all the mountains. The mother took them back with her unborn, and they opened their eyes and lived and fought in the valleys and on the slopes far to the west. If in later years Thor ever chased his own children out of his hunting grounds, or whipped them in a fight, Nature kindly blinded him to the fact. He was like most grouchy old bachelors: he did not like small folk. He tolerated a little cub as a cross-grained old woman-hater might have tolerated a pink baby; but he wasn't as cruel as Punch, for he had never killed a cub. He had cuffed them soundly whenever they had dared to come within reach of him, but always with the flat, soft palm of his paw, and with just enough force behind it to send them keeling over and over like little round fluffy balls.

This was Thor's only expression of displeasure when a strange mother-bear invaded his range with her cubs. In other ways he was quite chivalrous. He would not drive the mother-bear and her cubs away, and he would not fight with her, no matter how shrewish or unpleasant she was. Even if he found them eating at one of his kills, he would do nothing more than give the cubs a sound cuffing.

All this is somewhat necessary to show with what sudden and violent agitation Thor caught a certain warm, close smell as he came around the end of a mass of huge boulders. He stopped, turned his head, and swore in his low, growling way. Six feet away from him, grovelling flat in a patch of white sand, wriggling and shaking for all the world like a half-frightened puppy that had not yet made up its mind whether it had met a friend or an enemy, was a lone bear cub. It was not more than three months old—altogether too young to be away from its mother; and it had a sharp little tan face and a white spot on its baby breast which marked it as a member of the black bear family, and not a grizzly.

The cub was trying as hard as it could to say, "I am lost, strayed, or stolen; I'm hungry, and I've got a porcupine quill in my foot," but in spite of that, with another ominous growl, Thor began to look about the rocks for the mother. She was not in sight, and neither could he smell her, two facts which turned his great head again toward the cub.

Muskwa—an Indian would have called the cub that—had crawled a foot or two nearer on his little belly. He greeted Thor's second inspection with a genial wriggling which carried him forward another half foot, and a low warning rumbled in Thor's chest. "Don't come any nearer," it said plainly enough, "or I'll keel you over!"

Muskwa understood. He lay as if dead, his nose and paws and belly flat on the sand, and Thor looked about him again. When his eyes returned to Muskwa, the cub was within three feet of him, squirming flat in the sand and whimpering softly. Thor lifted his right paw four inches from the ground. "Another inch and I'll give you a welt!" he growled.

Muskwa wriggled and trembled; he licked his lips with his tiny red tongue, half in fear and half pleading for mercy, and in spite of Thor's lifted paw he wormed his way another six inches nearer.

There was a sort of rattle instead of a growl in Thor's throat. His heavy hand fell to the sand. A third time he looked about and sniffed the air; he growled again. Any crusty old bachelor would have understood that growl. "Now where the devil is the kid's mother!" it said.

Something happened then. Muskwa had crept close to Thor's wounded leg. He rose up, and his nose caught the scent of the raw wound. Gently his tongue touched it. It was like velvet—that tongue. It was wonderfully pleasant to feel, and Thor stood there for many moments, making neither movement nor sound while the cub licked his wound. Then he lowered his great head. He sniffed the soft little ball of friendship that had come to him. Muskwa whined in a motherless way. Thor growled, but more softly now. It was no longer a threat. The heat of his great tongue fell once on the cub's face.

"Come on!" he said, and resumed his journey into the north.

And close at his heels followed the motherless little tan-faced cub.

The creek which Thor was following was a tributary of the Babine, and he was headed pretty nearly straight for the Skeena. As he was travelling upstream the country was becoming higher and rougher. He had come perhaps seven or eight miles from the summit of the divide when he found Muskwa. From this point the slopes began to assume a different aspect. They were cut up by dark, narrow gullies, and broken by enormous masses of rocks, jagged cuffs, and steep slides of shale. The creek became noisier and more difficult to follow.

Thor was now entering one of his strongholds: a region which contained a thousand hiding-places, if he had wanted to hide; a wild, uptorn country where it was not difficult for him to kill big game, and where he was certain that the man-smell would not follow him.

For half an hour after leaving the mass of rocks where he had encountered Muskwa, Thor lumbered on as if utterly oblivious of the fact that the cub was following. But he could hear him and smell him.

Muskwa was having a hard time of it. His fat little body and his fat little legs were unaccustomed to this sort of journeying, but he was a game youngster, and only twice did he whimper in that half-hour—once he toppled off a rock into the edge of the creek, and again when he came down too hard on the porcupine quill in his foot.

At last Thor abandoned the creek and turned up a deep ravine, which he followed until he came to a dip, or plateau-like plain, halfway up a broad slope. Here he found a rock on the sunny side of a grassy knoll, and stopped. It may be that little Muskwa's babyish friendship, the caress of his soft little red tongue at just the psychological moment, and his perseverance in following Thor had all combined to touch a responsive chord in the other's big brute heart, for after nosing about restlessly for a few moments Thor stretched himself out beside the rock. Not until then did the utterly exhausted little tan-faced cub lie down, but when he did lie down he was so dead tired that he was sound asleep in three minutes.

Twice again during the early part of the afternoon the sapoos oowin worked on Thor, and he began to feel hungry. It was not the sort of hunger to be appeased by ants and grubs, or even gophers and whistlers. It may be, too, that he guessed how nearly starved little Muskwa was. The cub had not once opened his eyes, and he still lay in his warm pool of sunshine when Thor made up his mind to go on.

It was about three o'clock, a particularly quiet and drowsy part of a late June or early July day in a northern mountain valley. The whistlers had piped until they were tired, and lay squat out in the sunshine on their rocks; the eagles soared so high above the peaks that they were mere dots; the hawks, with meat-filled crops, had disappeared into the timber; goat and sheep were lying down far up toward the sky-line, and if there were any grazing animals near they were well fed and napping.

The mountain hunter knew that this was the hour when he should scan the green slopes and the open places between the clumps of timber for bears, and especially for flesh-eating bears.

It was Thor's chief prospecting hour. Instinct told him that when all other creatures were well fed and napping he could move more openly and with less fear of detection. He could find his game, and watch it. Occasionally he would kill a goat or a sheep or a caribou in broad daylight, for over short distances he could run faster than either a goat or a sheep, and as fast as a caribou. But chiefly he killed at sunset or in the darkness of early evening.

Thor rose from beside the rock with a prodigious whoof that roused Muskwa. The cub got up, blinked at Thor and then at the sun, and shook himself until he fell down.

Thor eyed the black and tan mite a bit sourly. After the sapoos oowin he was craving red, juicy flesh, just as a very hungry man yearns for a thick porterhouse instead of lady fingers or mayonnaise salad—flesh and plenty of it; and how he could hunt down and kill a caribou with that half-starved but very much interested cub at his heels puzzled him.

Muskwa himself seemed to understand and answer the question. He ran a dozen yards ahead of Thor, then stopped and looked back impudently, his little ears perked forward, and with the look in his face of a small boy proving to his father that he is perfectly qualified to go on his first rabbit hunt.

With another whoof Thor started along the slope in a spurt that brought him up to Muskwa immediately, and with a sudden sweep of his right paw he sent the cub rolling a dozen feet behind him, a manner of speech that said plainly enough, "That's where you belong if you're going hunting with me!"

Then Thor lumbered slowly on, eyes and ears and nostrils keyed for the hunt. He descended until he was not more than a hundred yards above the creek, and he no longer sought out the easiest trail, but the rough and broken places. He travelled slowly and in a zigzag fashion, stealing cautiously around great masses of boulders, sniffing up each coulee that he came to, and investigating the timber clumps and windfalls.

At one time he would be so high up that he was close to the bare shale, and again so low down that he walked in the sand and gravel of the creek. He caught many scents in the wind, but none that held or deeply interested him. Once, up near the shale, he smelled goat; but he never went above the shale for meat. Twice he smelled sheep, and late in the afternoon he saw a big ram looking down on him from a precipitous crag a hundred feet above.

Lower down his nose touched the trails of porcupines, and often his head hung over the footprints of caribou as he sniffed the air ahead.

There were other bears in the valley, too. Mostly these had travelled along the creek-bottom, showing they were blacks or cinnamons. Once Thor struck the scent of another grizzly, and he rumbled ill-humouredly.

Not once in the two hours after they left the sunrock did Thor pay any apparent attention to Muskwa, who was growing hungrier and weaker as the day lengthened. No boy that ever lived was gamer than the little tan-faced cub. In the rough places he stumbled and fell frequently; up places that Thor could make in a single step he had to fight desperately to make his way; three times Thor waded through the creek and Muskwa half drowned himself in following; he was battered and bruised and wet and his foot hurt him—but he followed. Sometimes he was close to Thor, and at others he had to run to catch up. The sun was setting when Thor at last found game, and Muskwa was almost dead.

He did not know why Thor flattened his huge bulk suddenly alongside a rock at the edge of a rough meadow, from which they could look down into a small hollow. He wanted to whimper, but he was afraid. And if he had ever wanted his mother at any time in his short life he wanted her now. He could not understand why she had left him among the rocks and had never come back; that tragedy Langdon and Bruce were to discover a little later. And he could not understand why she did not come to him now. This was just about his nursing hour before going to sleep for the night, for he was a March cub, and, according to the most approved mother-bear regulations, should have had milk for another month.

He was what Metoosin, the Indian, would have called munookow—that is, he was very soft. Being a bear, his birth had not been like that of other animals. His mother, like all mother-bears in a cold country, had brought him into life a long time before she had finished her winter nap in her den. He had come while she was asleep. For a month or six weeks after that, while he was still blind and naked, she had given him milk, while she herself neither ate nor drank nor saw the light of day. At the end of those six weeks she had gone forth with him from her den to seek the first mouthful of sustenance for herself. Not more than another six weeks had passed since then, and Muskwa weighed about twenty pounds—that is, he had weighed twenty pounds, but he was emptier now than he had ever been in his life, and probably weighed a little less.

Three hundred yards below Thor was a clump of balsams, a small thick patch that grew close to the edge of the miniature lake whose water crept around the farther end of the hollow. In that clump there was a caribou—perhaps two or three. Thor knew that as surely as though he saw them. The wenipow, or "lying down," smell of hoofed game was as different from the nechisoo, or "grazing smell," to Thor as day from night. One hung elusively in the air, like the faint and shifting breath of a passing woman's scented dress and hair; the other came hot and heavy, close to the earth, like the odour of a broken bottle of perfume.

Even Muskwa now caught the scent as he crept up close behind the big grizzly and lay down.

For fully ten minutes Thor did not move. His eyes took in the hollow, the edge of the lake, and the approach to the timber, and his nose gauged the wind as accurately as the pointing of a compass. The reason he remained quiet was that he was almost on the danger-line. In other words, the mountains and the sudden dip had formed a "split wind" in the hollow, and had Thor appeared fifty yards above where he now crouched, the keen-scented caribou would have got full wind of him.

With his little ears cocked forward and a new gleam of understanding in his eyes, Muskwa now looked upon his first lesson in game-stalking. Crouched so low that he seemed to be travelling on his belly, Thor moved slowly and noiselessly toward the creek, the huge ruff just forward of his shoulders standing out like the stiffened spine of a dog's back. Muskwa followed. For fully a hundred yards Thor continued his detour, and three times in that hundred yards he paused to sniff in the direction of the timber. At last he was satisfied. The wind was full in his face, and it was rich with promise.

He began to advance, in a slinking, rolling, rock-shouldered motion, taking shorter steps now, and with every muscle in his great body ready for action. Within two minutes he reached the edge of the balsams, and there he paused again. The crackling of underbrush came distinctly. The caribou were up, but they were not alarmed. They were going forth to drink and graze.

Thor moved again, parallel to the sound. This brought him quickly to the edge of the timber, and there he stood, concealed by foliage, but with the lake and the short stretch of meadow in view. A big bull caribou came out first. His horns were half grown, and in velvet. A two-year-old followed, round and sleek and glistening like brown velvet in the sunset. For two minutes the bull stood alert, eyes, ears, and nostrils seeking for danger-signals; at his heels the younger animal nibbled less suspiciously at the grass. Then lowering his head until his antlers swept back over his shoulders the old bull started slowly toward the lake for his evening drink. The two-year-old followed—and Thor came out softly from his hiding-place.

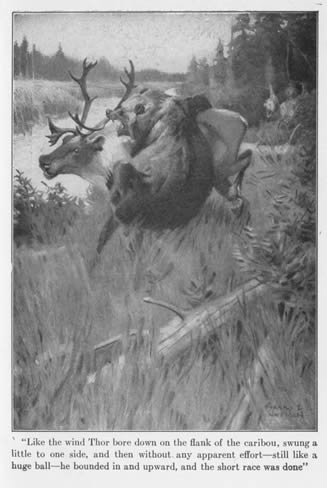

For a single moment he seemed to gather himself—and then he started. Fifty feet separated him from the caribou. He had covered half that distance like a huge rolling ball when the animals heard him. They were off like arrows sprung from the bow. But they were too late. It would have taken a swift horse to beat Thor and he had already gained momentum.

Like the wind he bore down on the flank of the two-year-old, swung a little to one side, and then without any apparent effort—still like a huge ball—he bounded in and upward, and the short race was done.

His huge right arm swung over the two-year-old's shoulder, and as they went down his left paw gripped the caribou's muzzle like a huge human hand. Thor fell under, as he always planned to fall. He did not hug his victim to death. Just once he doubled up one of his hind legs, and when it went back the five knives it carried disembowelled the caribou. They not only disembowelled him, but twisted and broke his ribs as though they were of wood. Then Thor got up, looked around, and shook himself with a rumbling growl which might have been either a growl of triumph or an invitation for Muskwa to come to the feast.

If it was an invitation, the little tan-faced cab did not wait for a second. For the first time he smelled and tasted the warm blood of meat. And this smell and taste had come at the psychological moment in his life, just as it had come in Thor's life years before. All grizzlies are not killers of big game. In fact, very few of them are. Most of them are chiefly vegetarians, with a meat diet of smaller animals, such as gophers, whistling marmots, and porcupines. Now and then chance makes of a grizzly a hunter of caribou, goat, sheep, deer, and even moose. Such was Thor. And such, in days to come, would Muskwa be, even though he was a black and not of the family Ursus Horribilis Ord.

For an hour the two feasted, not in the ravenous way of hungry dogs, but in the slow and satisfying manner of gourmets. Muskwa, flat on his little paunch, and almost between Thor's huge forearms, lapped up the blood and snarled like a kitten as he ground tender flesh between his tiny teeth. Thor, as in all his food-seeking, hunted first for the tidbits, though the sapoos oovin had made him as empty as a room without furniture. He pulled out the thin leafs of fat from about the kidneys and bowels, and munched at yard-long strings of it, his eyes half closed.

The last of the sun faded away from the mountains, and darkness followed swiftly after the twilight. It was dark when they finished, and little Muskwa was as wide as he was long.

Thor was the greatest of nature's conservators. With him nothing went to waste that was good to eat, and at the present moment if the old bull caribou had deliberately walked within his reach Thor in all probability would not have killed him. He had food, and his business was to store that food where it would be safe.

He went back to the balsam thicket, but the gorged cub now made no effort to follow him. He was vastly contented, and something told him that Thor would not leave the meat. Ten minutes later Thor verified his judgment by returning. In his huge jaws he caught the caribou at the back of the neck. Then he swung himself partly sidewise and began dragging the carcass toward the timber as a dog might have dragged a ten-pound slab of bacon.

The young bull probably weighed four hundred pounds. Had he weighed eight hundred, or even a thousand, Thor would still have dragged him—but had the carcass weighed that much he would have turned straight around and backed with his load.

In the edge of the balsams Thor had already found a hollow in the ground. He thrust the carcass into this hollow, and while Muskwa watched with a great and growing interest, he proceeded to cover it over with dry needles, sticks, a rotting tree butt, and a log. He did not rear himself up and leave his "mark" on a tree as a warning to other bears. He simply nosed round for a bit, and then went out of the timber.

Muskwa followed him now, and he had some trouble in properly navigating himself under the handicap of his added weight. The stars were beginning to fill the sky, and under these stars Thor struck straight up a steep and rugged slope that led to the mountain-tops. Up and up he went, higher than Muskwa had ever been. They crossed a patch of snow. And then they came to a place where it seemed as if a volcano had disrupted the bowels of a mountain. Man could hardly have travelled where Thor led Muskwa.

At last he stopped. He was on a narrow ledge, with a perpendicular wall of rock at his back. Under him fell away the chaos of torn-up rock and shale. Far below the valley lay a black and bottomless pit.

Thor lay down, and for the first time since his hurt in the other valley he stretched out his head between his great arms, and heaved a deep and restful sigh. Muskwa crept up close to him, so close that he was warmed by Thor's body; and together they slept the deep and peaceful sleep of full stomachs, while over them the stars grew brighter, and the moon came up to flood the peaks and the valley in a golden splendour.

Langdon and Bruce crossed the summit into the westward valley in the afternoon of the day Thor left the clay wallow. It was two o'clock when Bruce turned back for the three horses, leaving Langdon on a high ridge to scour the surrounding country through his glasses. For two hours after the packer returned with the outfit they followed slowly along the creek above which the grizzly had travelled, and when they camped for the night they were still two or three miles from the spot where Thor came upon Muskwa. They had not yet found his tracks in the sand of the creek bottom. Yet Bruce was confident. He knew that Thor had been following the crests of the slopes.

"If you go back out of this country an' write about bears, don't make a fool o' yo'rself like most of the writin' fellows, Jimmy," he said, as they sat back to smoke their pipes after supper. "Two years ago I took a natcherlist out for a month, an' he was so tickled he said 'e'd send me a bunch o' books about bears an' wild things. He did! I read 'em. I laughed at first, an' then I got mad an' made a fire of 'em. Bears is cur'ous. There's a mighty lot of interestin' things to say about 'em without making a fool o' yo'rself. There sure is!"

Langdon nodded.

"One has to hunt and kill and hunt and kill for years before he discovers the real pleasure in big game stalking," he said slowly, looking into the fire. "And when he comes down to that real pleasure, the part of it that absorbs him heart and soul, he finds that after all the big thrill isn't in killing, but in letting live. I want this grizzly, and I'm going to have him. I won't leave the mountains until I kill him. But, on the other hand, we could have killed two other bears to-day, and I didn't take a shot. I'm learning the game, Bruce—I'm beginning to taste the real pleasure of hunting. And when one hunts in the right way one learns facts. You needn't worry. I'm going to put only facts in what I write."

Suddenly he turned and looked at Bruce.

"What were some of the 'fool things' you read in those books?" he asked.

Bruce blew out a cloud of smoke reflectively.

"What made me maddest," he said, "was what those writer fellows said about bears havin' 'marks.' Good Lord, accordin' to what they said all a bear has to do is stretch 'imself up, put a mark on a tree, and that country is his'n until a bigger bear comes along an' licks 'im. In one book I remember where a grizzly rolled a log up under a tree so he could stand on it an' put his mark above another grizzly's mark. Think of that!

"No bear makes a mark that means anything. I've seen grizzlies bite hunks out o' trees an' scratch 'em just as a cat might, an' in the summer when they get itchy an' begin to lose their hair they stand up an' rub against trees. They rub because they itch an' not because they're leavin' their cards for other bears. Caribou an' moose an' deer do the same thing to get the velvet off their horns.

"Them same writers think every grizzly has his own range, an' they don't—not by a long shot they don't! I've seen eight full-grown grizzlies feedin' on the same slide! You remember, two years ago, we shot four grizzlies in a little valley that wasn't a mile long. Now an' then there's a boss among grizzlies, like this fellow we're after, but even he ain't got his range alone. I'll bet there's twenty other bears in these two valleys! An' that natcherlist I had two years ago couldn't tell a grizzly's track from a black bear's track, an so 'elp me if he knew what a cinnamon was!"

He took his pipe from his mouth and spat truculently into the fire, and Langdon knew that other things were coming. His richest hours were those when the usually silent Bruce fell into these moods.

"A cinnamon!" he growled. "Think of that, Jimmy—he thought there were such a thing as a cinnamon bear! An' when I told him there wasn't, an' that the cinnamon bear you read about is a black or a grizzly of a cinnamon colour, he laughed at me—an' there I was born an' brung up among bears! His eyes fair popped when I told him about the colour o' bears, an' he thought I was feedin' him rope. I figgered afterward mebby that was why he sent me the books. He wanted to show me he was right.

"Jimmy, there ain't anything on earth that's got more colours than a bear! I've seen black bears as white as snow, an' I've seen grizzlies almost as black as a black bear. I've seen cinnamon black bears an' I've seen cinnamon grizzlies, an' I've seen browns an' golds an' almost-yellows of both kinds. They're as different in colour as they are in their natchurs an' way of eatin'.

"I figger most natcherlists go out an' get acquainted with one grizzly, an' then they write up all grizzlies accordin' to that one. That ain't fair to the grizzlies, darned if it is! There wasn't one of them books that didn't say the grizzly wasn't the fiercest, man-eatingest cuss alive. He ain't—unless you corner 'im. He's as cur'ous as a kid, an' he's good-natured if you don't bother 'im. Most of 'em are vegetarians, but some of 'em ain't. I've seen grizzlies pull down goat an' sheep an' caribou, an' I've seen other grizzlies feed on the same slides with them animals an' never make a move toward them. They're cur'ous, Jimmy. There's lots you can say about 'em without makin' a fool o' yourself!"

Bruce beat the ash out of his pipe as an emphasis to his final remark. As he reloaded with fresh tobacco, Langdon said:

"You can make up your mind this big fellow we are after is a game-killer, Bruce."

"You can't tell," replied Bruce. "Size don't always tell. I knew a grizzly once that wasn't much bigger'n a dog, an' he was a game-killer. Hundreds of animals are winter-killed in these mount'ins every year, an' when spring comes the bears eat the carcasses; but old flesh don't make game-killers. Sometimes it's born in a grizzly to be a killer, an' sometimes he becomes a killer by chance. If he kills once, he'll kill again.

"Once I was on the side of a mount'in an' saw a goat walk straight into the face of a grizzly. The bear wasn't going to make a move, but the goat was so scared it ran plump into the old fellow, and he killed it. He acted mighty surprised for ten minutes afterward, an' he sniffed an' nosed around the warm carcass for half an hour before he tore it open. That was his first taste of what you might call live game. I didn't kill him, an' I'm sure from that day on he was a big-game hunter."