This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Christie, the King's Servant

Author: Mrs. O. F. Walton

Release Date: January 16, 2004 [eBook #10728]

Language: English

Character set encoding: iso-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CHRISTIE, THE KING'S SERVANT***

Chapter XI LITTLE JACK AND BIG JACK

Chapter XII WHERE ARE YOU GOING?

It was the yellow ragwort that did it! I have discovered the clue at last. All night long I have been dreaming of Runswick Bay. I have been climbing the rocks, talking to the fishermen, picking my way over the masses of slippery seaweed, and breathing the fresh briny air. And all the morning I have been saying to myself, 'What can have made me dream of Runswick Bay? What can have brought the events of my short stay in that quaint little place so vividly before me?' Yes, I am convinced of it; it was that bunch of yellow ragwort on the mantelpiece in my bedroom. My little Ella gathered it in the lane behind the house yesterday morning, and brought it in triumphantly, and seized the best china vase in the drawing-room, and filled it with water at the tap, and thrust the great yellow bunch into it.

'Oh, Ella,' said Florence, her elder sister, 'what ugly common flowers! How could you put them in mother's best vase, that Aunt Alice gave her on her birthday! What a silly child you are!'

'I'm not a silly child,' aid Ella stoutly, 'and mother is sure to like them; I know she will. She won't call them common flowers. She loves all yellow flowers. She said so when I brought her the daffodils; and these are yellower, ever so much yellower.'

Her mother came in at this moment, and, taking our little girl on her knee, she told her that she was quite right; they were very beautiful in her eyes, and she would put them at once in her own room, where she could have them all to herself.

And that is how it came about, that, as I lay in bed, the last thing my eyes fell upon was Ella's bunch of yellow ragwort; and what could be more natural than that I should go to sleep and dream of Runswick Bay?

It seems only yesterday that I was there, so clearly can I recall it, and yet it must be twenty years ago. I think I must write an account of my visit to Runswick Bay and give it to Ella, as it was her yellow flowers which took me back to the picturesque little place. If she cannot understand all I tell her now, she will learn to do so as she grows older.

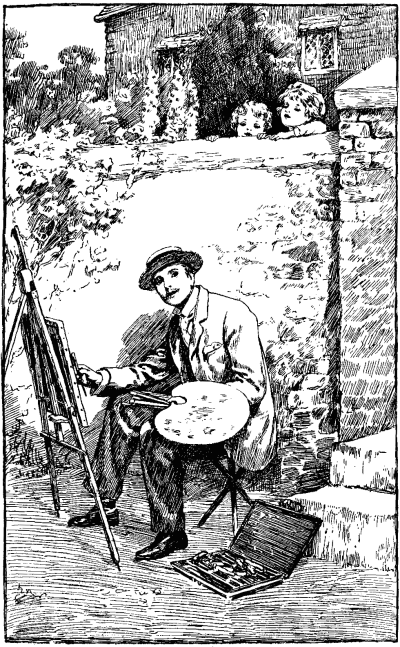

I was a young man then, just beginning to make my way as an artist. It is slow work at first; until you have made a name, every one looks critically at your work; when once you have been pronounced a rising artist, every daub from your brush has a good market value. I had had much uphill work, but I loved my profession for its own sake, and I worked on patiently, and, at the time my story begins, several of my pictures had sold for fair prices, and I was not without hope that I might soon find a place in the Academy.

It was an unusually hot summer, and London was emptying fast. Every one who could afford it was going either to the moors or to the sea, and I felt very much inclined to follow their example. My father and mother had died when I was quite a child, and the maiden aunt who had brought me up had just passed away, and I had mourned her death very deeply, for she had been both father and mother to me. I felt that I needed change of scene, for I had been up for many nights with her during her last illness, and I had had my rest broken for so long, that I found it very difficult to sleep, and in many ways I was far from well. My aunt had left all her little property to me, so that the means to leave London and to take a suitable holiday were not wanting. The question was, where should I go? I was anxious to combine, if possible, pleasure and business—that is to say, I wished to choose some quiet place where I could get bracing air and thorough change of scene, and where I could also find studies for my new picture, which was (at least, so I fondly dreamed) to find a place in the Academy the following spring.

It was whilst I was looking for a suitable spot that Tom Bernard, my great friend and confidant, found one for me.

'Jack, old fellow,' he said, thrusting a torn newspaper into my hand, 'read that, old man.'

The newspaper was doubled down tightly, and a great red cross of Tom's making showed me the part he wished me to read.

RUNSWICK BAY. This charming seaside resort is not half so well known as it deserves to be. For the lover of the beautiful, for the man with an artistic eye, it possesses a charm which words would fail to describe. The little bay is a favourite resort for artists; they, at least, know how to appreciate its beauties. It would be well for any who may desire to visit this wonderfully picturesque and enchanting spot to secure hotel or lodging-house accommodation as early as possible, for the demand for rooms is, in August and September, far greater than the supply.

'Well, what do you think of it?' said Tom.

'It sounds just the thing,' I said; 'fresh air and plenty to paint.'

'Shall you go?'

'Yes, to-morrow,' I replied; 'the sooner the better.'

My bag was soon packed, my easel and painting materials were collected, and the very next morning I was on my way into Yorkshire.

It was evening when I reached the end of my long, tiring railway journey; and when, hot and dusty, I alighted at a village which lay about two miles from my destination. I saw no sign of beauty as I walked from the station; the country was slightly undulating in parts, but as a rule nothing met my gaze but a long flat stretch of field after field, covered, as the case might be, with grass or corn. Harebells and pink campion grew on the banks, and the meadows were full of ox-eye daisies; but I saw nothing besides that was in the least attractive, and certainly nothing of which I could make a picture.

A family from York had come by the same train, and I had learnt from their conversation that they had engaged lodgings for a month at Runswick Bay. The children, two boys of ten and twelve, and a little fair-haired girl a year or two younger, were full of excitement on their arrival.

'Father, where is the sea?' they cried. 'Oh, we do want to see the sea!'

'Run on,' said their father, 'and you will soon see it.'

So we ran together, for I felt myself a child again as I watched them, and if ever I lagged behind, one or other of them would turn round and cry, 'Come on, come on; we shall soon see it.'

Then, suddenly, we came to the edge of the high cliff, and the sea in all its beauty and loveliness burst upon us. The small bay was shut in by rocks on either side, and on the descent of the steep cliff was built the little fishing village. I think I have never seen a prettier place.

The children were already running down the steep, rocky path—I cannot call it a road—which led down to the sea, and I followed more slowly behind them. It was the most curiously built place. The fishermen's cottages were perched on the rock, wherever a ledge or standing place could be found. Steep, narrow paths, or small flights of rock-hewn steps, led from one to another. There was no street in the whole place; there could be none, for there were hardly two houses which stood on the same level. To take a walk through this quaint village was to go up and down stairs the whole time.

At last, after a long, downward scramble, I found myself on the shore, and then I looked back at the cliff and at the irregular little town. I did not wonder that artists were to be found there. I had counted four as I came down the hill, perched on different platforms on the rock, and all hard at work at their easels.

Yes, it was certainly a picturesque place, and I was glad that I had come. The colouring was charming: there was red rock in the background, here and there covered with grass, and ablaze with flowers. Wild roses and poppies, pink-thrift and white daisies, all contributed to make the old rock gay. But the yellow ragwort was all over; great patches of it grew even on the margin of the sand, and its bright flowers gave the whole place a golden colouring. There seemed to be yellow everywhere, and the red-tiled cottages, and the fishermen in their blue jerseys, and the countless flights of steps, all appeared to be framed in the brightest gilt.

Yes, I felt sure I should find something to paint in Runswick Bay. I was not disappointed in Tom's choice for me.

After admiring the beauties of my new surroundings for some little time, I felt that I must begin to look for quarters. I was anxious, if possible, to find a lodging in one of the cottages, and then, after a good night's rest, I would carefully select a good subject for my picture. I called at several houses, where I noticed a card in the window announcing Apartments to Let, but I met the same answer everywhere, 'Full, sir, quite full.' In one place I was offered a bed in the kitchen, but the whole place smelt so strongly of fried herrings and of fish oil, that I felt it would be far more pleasant to sleep on the beach than to attempt to do so in that close and unwholesome atmosphere.

After wandering up and down for some time, I passed a house close to the village green, and saw the children with whom I had travelled sitting at tea close to the open window. They, too, were eating herrings, and the smell made me hungry. I began to feel that it was time I had something to eat, and I thought my best plan would be to retrace my steps to the hotel which I had passed on my way, and which stood at the very top of the high cliff. I turned a little lazy when I thought of the climb, for I was tired with my journey, and, as I said before, I was not very strong, and to drag my bag and easel up the rugged ascent would require a mighty effort at the best of times. I noticed that wooden benches had been placed here and there on the different platforms of the rock, for the convenience of the fishermen, and I determined to rest for a quarter of an hour on one of them before retracing my steps up the steep hill to the hotel. The fishermen were filling most of the seats, sitting side by side, row after row of them, talking together, and looking down at the beach below. As I gazed up at them, they looked to me like so many blue birds perched on the steep rock.

There was one seat in a quiet corner which I noticed was empty. I went to it, and laying my knapsack and other belongings beside me, I sat down to rest.

But I was not long to remain alone. A minute afterwards a young fisherman, dressed like his mates in blue jersey and oilskin cap, planted himself on the other end of the seat which I had selected.

'Good-day, sir,' he said. 'What do you think of our bay?'

'It's a pretty place, very pretty,' I said. 'I like it well enough now, but I daresay I shall like it better still to-morrow.'

'Better still to-morrow,' he repeated; 'well, it is the better for knowing, in my opinion, sir, and I ought to know, if any one should, for I've lived my lifetime here.'

I turned to look at him as he spoke, and I felt at once that I had come across one of Nature's gentlemen. He was a fine specimen of an honest English fisherman, with dark eyes and hair, and with a sunny smile on his weather-beaten, sunburnt face. You had only to look at the man to feel sure that you could trust him, and that, like Nathanael, there was no guile in him.

'I wonder if you could help me,' I said; 'I want to find a room here if I can, but every place seems so full.'

'Yes, it is full, sir, in August; that's the main time here. Let me see, there's Brown's, they're full, and Robinson's, and Wilson's, and Thomson's, all full up. There's Giles', they have a room, I believe, but they're not over clean; maybe you're particular, sir.'

'Well,' I said, 'I do like things clean; I don't mind how rough they are if they're only clean.'

'Ah,' he said, with a twinkle in his eye; 'you wouldn't care for one pan to do all the work of the house—to boil the dirty clothes, and the fish, and your bit of pudding for dinner, and not overmuch cleaning of it in between.'

'No,' I said, laughing; 'I should not like that, certainly.'

'Might give the pudding a flavour of stockings, and a sauce of fish oil,' he answered. 'Well, you're right, sir; I shouldn't like it myself. Cleanliness is next to godliness, that's my idea. Well, then, that being as it is, I wouldn't go to Giles', not if them is your sentiments with regard to pans, sir.'

'Then I suppose there's nothing for it but to trudge up to the hotel at the top of the hill,' I said, with something of a groan.

'Well, sir,' he said, hesitating a little; 'me and my missus, we have a room as we lets sometimes, but it's a poor place, sir, homely like, as ye may say. Maybe you wouldn't put up with it.'

'Would you let me see it?' I asked.

'With pleasure, sir; it's rough, but it's clean. We could promise you a clean pan, sir. My missus she's a good one for cleaning; she's not one of them slatternly, good-for-nothing lasses. There's heaps of them here, sir, idling away their time. She's a good girl is my Polly. Why, if that isn't little John a-clambering up the steps to his daddy!'

He jumped up as he said this, and ran quickly down the steep flight of steps which led down from the height on which the seat was placed, and soon returned with a little lad about two years old in his arms.

The child was as fair as his father was dark. He was a pretty boy with light hair and blue eyes, and was tidily dressed in a bright red cap and clean white-pinafore.

'Tea's ready, daddy,' said the boy; 'come home with little John.'

'Maybe you wouldn't object to a cup o' tea, sir,' said the father, turning to me; 'it'll hearten you up a bit after your journey, and there's sure to be herrings. We almost lives on herrings here, sir, and then, if you're so minded, you can look at the room after. Ye'll excuse me if I make too bold, sir,' he added, as he gently patted little John's tiny hand, which rested on his arm.

'I shall be only too glad to come,' I said; 'for I am very hungry, and if Polly's room is as nice as I think it will be, it will be just the place for me.'

He walked in front of me, up and down several flights of steps, until, at some little distance lower down the hill, he stopped before a small cottage. Sure enough there were herrings, frying and spluttering on the fire, and there too was Polly herself, arrayed in a clean white apron, and turning the herrings with a fork. The kitchen was very low, and the rafters seemed resting on my head as I entered; but the window and door were both wide open, and the whole place struck me as being wonderfully sweet and clean. A low wooden settle stood by the fire, one or two plain deal chairs by the wall, and little John's three-legged stool was placed close to his father's arm-chair. A small shelf above the fireplace held the family library. I noticed a Bible, a hymn-book, a Pilgrim's Progress, and several other books, all of which had seen their best days and were doubtless in constant use. On the walls were prints in wooden frames and much discoloured by the turf smoke of the fire. Upon a carved old oak cupboard, which held the clothes of the family, were arranged various rare shells and stones, curious sea-urchins and other treasures of the sea, and in the centre, the chief ornament of the house and the pride of Polly's heart, a ship, carved and rigged by Duncan himself, and preserved carefully under a glass shade.

Polly gave me a hearty Yorkshire welcome, and we soon gathered about the small round table. Duncan, with little John on his knee, asked a blessing, and Polly poured out the tea, and we all did justice to the meal.

The more I saw of these honest people, the more I liked them and felt inclined to trust them. When tea was over, Polly took me to see the guest-chamber in which her husband had offered me a bed. It was a low room in the roof, containing a plain wooden bedstead, one chair, a small wash-hand stand, and a square of looking-glass hanging on the wall. There was no other furniture, and, indeed, there was room for no other, and the room was unadorned except by three or four funeral cards in dismal black frames, which were hanging at different heights on the wall opposite the bed. But the square casement window was thrown wide open, and the pure sea air filled the little room, and the coarse white coverings of the bed were spotless, and, indeed, the whole place looked and felt both fresh and clean.

'You'll pardon me, sir,' said Duncan, 'for asking you to look at such a poor place.'

'But I like it, Duncan,' I answered, 'and I like you, and I like your wife, and if you will have me as a lodger, I am willing and glad to stay.'

The terms were soon agreed upon to the satisfaction of both parties, and then all things being settled, Polly went to put little John to bed whilst I went with Duncan to see his boat.

It was an old boat, and it had been his father's before him, and it had weathered many a storm; but it was the dream of Duncan's life to buy a new one, and he and Polly had nearly saved up money enough for it.

'That's why me and the missus is glad to get a lodger now and again,' he said; 'it all goes to the boat, every penny of it. We mean to call her The Little John. He's going in her the very first voyage she takes; he is indeed, sir, for he'll be her captain one day, please God, little John will.'

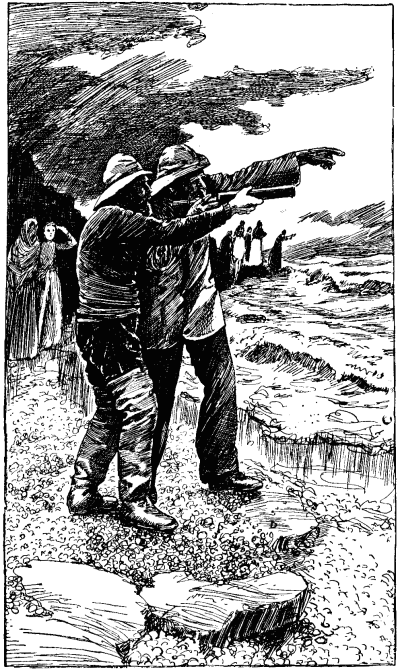

It was a calm, beautiful evening; the sea was like a sheet of glass. Hardly a ripple was breaking on the shore. The sun was setting behind the cliff, and the fishing village would soon be in darkness. The fishermen were leaving their cottages and were making for the shore. Already some of the boats were launched, and the men were throwing in their nets and fishing-tackle, and were pulling out to sea. I enjoyed watching my new friend making his preparations. His three mates brought out the nets, and he gave his orders with a tone of command. He was the owner and the captain of the Mary Ann, and the rest were accustomed to do his bidding.

When all were on board, Duncan himself jumped in and gave the word to push from shore. He nodded to me and bid me good-night, and when he was a little way from shore, I saw him stand up in the boat and wave his oil-skin cap to some one above me on the cliff.

I looked up, and saw Polly standing on the rock overhanging the shore with little John in his white nightgown in her arms. He was waving his red cap to his father, and continued to do so till the boat was out of sight.

I slept well in my strange little bedroom, although I was awakened early by the sunlight streaming in at the window. I jumped up and looked out. The sun was rising over the sea, and a flood of golden light was streaming across it.

I dressed quickly and went out. Very few people were about, for the fishermen had not yet returned from their night's fishing. The cliff looked even more beautiful than the night before, for every bit of colouring stood out clear and distinct in the sunshine. 'I shall get my best effects in the morning,' I said to myself, 'and I had better choose my subject at once, so that after breakfast I may be able to begin without delay.'

How many steps I went up, and how many I went down, before I came to a decision, it would be impossible to tell; but at last I found a place which seemed to me to be the very gem of the whole village. An old disused boat stood in the foreground, and over this a large fishing net, covered with floats, was spread to dry. Behind rose the rocks, covered with tufts of grass, patches of gorse, tall yellow mustard plants and golden ragwort, and at the top of a steep flight of rock-hewn steps stood a white cottage with red-tiled roof, the little garden in front of it gay with hollyhocks and dahlias. A group of barefooted children were standing by the gate feeding some chickens and ducks, a large dog was lying asleep at the top of the steps, and a black cat was basking in the morning sunshine on the low garden wall. It was, to my mind, an extremely pretty scene, and it made me long to be busy with my brush.

I hurried back to my lodging, and found Polly preparing my breakfast, whilst little John looked on. He was sitting in his nightgown, curled up in his father's armchair. 'I'm daddy,' he called out to me as I came in.

There was a little round table laid ready for me, and covered with a spotlessly clean cloth, and on it was a small black teapot, and a white and gold cup and saucer, upon which I saw the golden announcement, 'A present from Whitby,' whilst my plate was adorned with a remarkable picture of Whitby Abbey in a thunderstorm.

There were herrings, of course, and Polly had made some hot cakes, the like of which are never seen outside Yorkshire. These were ready buttered, and were lying wrapped in a clean cloth in front of the fire. Polly made the tea as soon as I entered, and then retired with little John in her arms into the bedroom, whilst I sat down with a good appetite to my breakfast.

I had not quite finished my meal when I heard a great shout from the shore. Women and children, lads and lasses, ran past the open door, crying, 'The boats! the boats!' Polly came flying into the kitchen, caught up little John's red cap, thrust it on his head, and ran down the steps. I left my breakfast unfinished, and followed them.

It was a pretty sight. The fishing-boats were just nearing shore, and almost every one in the place had turned out to meet them.

Wives, children, and visitors were gathered on the small landing place; most had dishes or plates in their hands, for the herrings could be bought straight from the boats. The family from York were there, and they greeted me as an old friend.

When the little village had been abundantly supplied with fish, the rest of the herrings were packed up and sent off by train to be sold elsewhere. It was a pretty animated scene, and I wished I had brought my sketchbook with me. I thought the arrival of the fishing boats would make a splendid subject for a picture.

Duncan was too busy even to see me till the fish were all landed, counted, and disposed of, but he had time for a word with little John, and as I was finishing my breakfast he came in with the child perched on his shoulder.

'Good morning, sir,' he said; 'and how do you like our bay this morning?'

My answer fully satisfied him, and whilst he sat down to his morning meal I went out to begin my work. It was a lovely day, and I thoroughly enjoyed the prospect before me. I found a shady place just under the wall of a house, where my picture would be in sunlight and I and my easel in shadow. I liked the spot I had chosen even better than I had done before breakfast, and I was soon hard at work.

I had sketched in my picture, and was beginning to paint, when I became conscious of the sound of voices just over my head, and I soon became equally conscious that they were talking about me.

'It's just like it,' said one voice. 'Look—do look. There's Betty Green's cottage, and Minnie the cat, and the seat, and the old boat.'

'Let me see, Marjorie,' said another voice; 'is it the old one with white hair and a long, long beard?'

'No, it's quite a young one; his hair's black, and he hasn't got a beard at all.'

'Let me look. Yes, I can see him. I like him much better than the old one; hasn't he got nice red cheeks?'

'Hush! he'll hear,' said the other voice. 'You naughty boy! I believe he did hear; I saw him laugh.'

I jumped up at this, and looked up, but I could see nothing but a garden wall and a thick bushy tree, which was growing just inside it.

'Hullo, who's there?' I shouted.

But there was dead silence; and as no one appeared, and nothing more happened, I sat down and went on with my picture.

Many people passed by as I was painting, and tried to look at what I was doing. Some glanced out of the corners of their eyes as they walked on; others paused behind me and silently watched me; a few made remarks to one another about my picture; one or two offered suggestions, thought I should have had a better view lower down the hill, or hoped that I would make the colouring vivid enough. The children with whom I had travelled seemed to feel a kind of partnership in my picture.

'Let's go and look at our artist,' Bob would say to Harry; 'his picture is going to be the best of the lot.'

They were so fond of watching me, and so much excited over what I was doing, that, as time went on, I was often obliged to ask them to move further away, so eager were they to watch every movement of my brush.

I thoroughly enjoyed my morning's work, and went back very hungry, and quite ready for the comfortable little dinner which Polly had prepared for me. In the afternoon the light would be all wrong for my picture; but I determined to sketch in the foreground, and prepare for my next morning's work.

I was very busy upon this, when suddenly I became conscious of music, if music it could be called. It was the most peculiar sound, and at first I could not find out from whence it came. It was evidently not caused by a wind instrument; I felt sure it was not a concertina or an accordion. This sound would go on for a minute or two, and then stop suddenly, only to begin again more loudly a few seconds later. At times I distinguished a few bars of a tune, then only disjointed notes followed. Could it be a child strumming idly on a harmonium? but no, it was not at all like an instrument of that kind. It was an annoying, worrying sound, and it went on for so long that I began to be vexed with it, and stamped my foot impatiently when, after a short interval, I heard it begin again. The sound seemed to come from behind the wall of the house near which I was sitting, and it was repeated from time to time during the whole of the afternoon.

At length, as the afternoon went on, I began to distinguish what tunes were being attempted. I made out a bar or two of the old French Republican air, 'The Marseillaise,' and then I was almost startled by what came next, for it was a tune I had known well since I was a very little child. It was 'Home, Sweet Home,' and that was my mother's favourite tune; in fact, I never heard it without thinking of her. Many and many a time had she sung me to sleep with that tune. I had scarlet fever when I was five years old, and my mother had nursed me through it, and when I was weary and fretful she would sing to me—my pretty fair-haired mother. Even as I sat before my easel I could see her, as she sat at the foot of my bed, with the sunshine streaming upon her through the half-darkened window, and making her look, to my boyish imagination, like a beautiful angel. And I could hear her voice still; and the sweet tones in which she sang that very song to me, 'Home, sweet home, there's no place like home.'

I remembered one night especially, in which she knelt by my bed and prayed that she might meet her boy in the bright city, the sweet home above the sky which was the best and brightest home of all. I wonder what she would think of me now, I said to myself, and whether she ever will see me there. I very much doubt it; it seems to me that I am a long way off from Home, Sweet Home now.

My mother had died soon after that illness of mine, and I knew that she had gone to live in that beautiful home of which she had so often spoken to me. And I had been left behind, and my aunt, who had brought me up, had cared for none of these things, and I had learnt to look at the world and at life from her worldly standpoint, and had forgotten to seek first the Kingdom of God. Oh! if my mother only knew, my pretty, beautiful mother, I said to myself that day. And then there came the thought, perhaps she does know, and the thought made me very uncomfortable. I wished, more than ever, that that cracked old instrument, whatever it was, would stop.

But, in spite of all my wishes, the strange sound went on, and again and again I had to listen to 'Home, Sweet Home,' and each time that it came it set my memory going, and brought back to me the words and the looks which I thought I had forgotten. And it set something else going too—the still, small voice within, accusing me of forgetfulness, not so much of my mother as of my mother's God.

I began to wish most heartily that I had chosen some other spot for my picture. But it was working out so well that I felt it would be a great mistake to change, and I hoped that the individual, man, woman, or child, who had been making that horrible noise might find some other employment to-morrow, and might leave me in peace.

The next day my wishes were fulfilled, for I was not disturbed, and very little happened except that my picture made progress. Then came two wet days, on which I had to paint in my little chamber, and did not get back to my seat under the wall.

I saw a good deal of Duncan during those wet days. He would come and sit beside me as I painted, and would tell me stories of storms and shipwrecks, and of the different times when the lifeboat had been sent out, and of the many lives she had saved.

'Have ye seen her, sir? You must go and have a look at our boat; she lies in a house down by the shore, as trim and tight a little boat as you could wish to see anywhere!'

'I suppose you've been in many a storm yourself, Duncan,' I said.

'Storms, sir! I've very near lived in them ever since I was born. Many and many's the time I've never expected to see land again. I didn't care so much when I was a young chap. You see, my father and mother were dead, and if I went to the bottom there was nobody, as you might say, to feel it; but it's different now, sir, you see.'

'Yes,' I said, 'there's Polly and little John.'

'That's just where it is, sir, Polly and little John, bless 'em; and all the time the wind's raging, and the waves is coming right over the boat, I'm thinking of my poor lass at home, and how every gust of wind will be sweeping right over her heart, and how she'll be kneeling by little John's bed, praying God to bring his daddy safe home again. And I know, sir, as well as I know anything, that when God Almighty hears and answers her prayer, and brings me safe to land, Polly and little John will be standing on yon rocks a-straining their eyes for the first sight of the boats, and then a-running down almost into the water to welcome me home again. Yes, it makes a sight o' difference to a married man, sir; doesn't it, now? It isn't the dying, ye understand, it's the leaving behind as I think of. I'm not afraid to die,' he added humbly and reverently, as he took off his oilskin cap. 'I know whom I have believed.'

'You're a plucky fellow, Duncan,' I said, 'to talk of not being afraid to die. I've just been at a death-bed, and—'

'And you felt you wouldn't like to be there yourself,' Duncan went on, as I stopped. 'Well, maybe not, it comes nat'ral to us, sir; we're born with that feeling, I often think, and we can no more help it than we can help any other thing we're born with. But what I mean to say is, I'm not afraid of what comes after death. It may be a dark tunnel, sir, but there's light at the far end!'

On Saturday of that week the sun shone brightly, and I was up betimes, had an early breakfast, and set to work at my picture as soon as possible. I had not been painting long before I again heard voices above me, the same childish voices that I had heard before.

'You give it to him,' said one voice.

'No, Marjorie, I daren't; you take it.'

'You ought not to be afraid, because you're a boy,' said the first speaker; 'father says boys ought always to be brave.'

'But you're big, Marjorie, and big people ought to be braver than little people!'

There was a long, whispered conversation after this, and I could not distinguish the words which were spoken. But presently a small piece of pink paper was thrown over the wall, and fluttered down upon my palette. I caught it up quickly, to prevent it from sticking to the paints, and I saw there was something printed on it. It ran thus:—

There will be a short service on the shore on Sunday Morning at 11 o'clock, when you are earnestly requested to be present.

'Thank you,' I said aloud. 'Who sent me this?'

There was no answer at first, then a little voice just above me said, 'Both of us, sir.'

'Come down and talk to me,' I said; 'I can't talk to children whom I can't see. Come out here and look at my picture.'

They came out presently hand in hand, a little girl of five in a blue tam-o'-shanter cap, a pale pink frock, and a white pinafore, and a boy of three, the merriest, most sturdy little fellow I thought I had ever seen. His face was as round and rosy as an apple, his eyes were dark blue, and had the happiest and most roguish expression that it would be possible for eyes to have. When the child laughed (and whenever was he not laughing?), every part of his face laughed together. His eyes began it, his lips followed suit, even his nose was pressed into the service. If a sunbeam could be caught and dressed up like a little boy, I think it would look something like that child.

'Now,' I said, 'that's right; I like to see children's faces when I talk to them; tell me your names to begin with.'

'I'm Marjorie, sir,' said the little girl, 'and he's Jack.'

'Jack!' I said; 'that's my name, and a nice name too, isn't it, little Jack? Come and look at my picture, little Jack, and see if you think big Jack knows how to paint.'

By degrees they grew more at their ease, and chatted freely with me. Marjorie told me that her father had sent the paper. Father was going to preach on Sunday; he preached every Sunday, and numbers of people came, and Jack was in the choir.

What a dear little chorister, to be sure, a chubby little cherub if ever there was one!

'Shall you come, big Jack?' he said, patting my hand with his strong, sturdy little fist.

'I don't know,' I said; 'if it's a fine day, perhaps I shall want to get on with my picture.'

'On Sunday?' said the child in a shocked voice; 'it's on Sunday father preaches, and you couldn't paint on Sunday, could you?'

'Well, I'll see,' I said; 'perhaps I'll come and hear you sing, little Jack.'

'Thank you, big Jack,' he said, with a merry twinkle in his pretty blue eyes.

'What is this preaching on the shore, Duncan?' I asked.

'Oh, it's our lay preacher,' he said; 'he's a good man, and has done a sight of good in this place. You see, it's too far for folks here to go to church, and so he lives amongst us, and has meetings in the hall yonder in winter, and in summer, why, we have 'em on the shore, and the visitors comes mostly. There's a few won't come, but we get the best of them, and we have some fine singing—real nice it is! I'm in the choir myself, sir,' he said; 'you wouldn't think it, but I am. I've got a good strong voice, too!'

It must be a choir worth seeing, I thought, if it contained two such strange contrasts, the big burly fisherman and the tiny child who had invited me to be present.

I had not quite made up my mind to go. I had not been to a service for many months, I might almost say years. I had slipped out of it lately, and I thought I should feel myself a fish out of water. However, when the next day came, every one seemed to take it as a matter of course that I should be going. Polly was up early, and had dressed little John in his best.

'You'll see him at church, sir,' she said, as she laid my breakfast; 'he always likes to go to church, and he's as good as gold, bless him!'

Duncan was out before I was up, and I had seen him, as I was dressing, going round to the fishermen sitting as usual on the seats on the cliff, with a bundle of pink papers in his hand, similar to the one which had been given me, and distributing them to every group of his mates which he came across. Yes, I felt that I was expected to go, and it would be hard work to keep away. But if I had still had any doubt about the matter, it would have surely disappeared when at half-past ten exactly a tiny couple came toiling hand in hand up the steps leading to Duncan's door, and announced to Polly that they had come to call for big Mr. Jack to go to church.

It was Marjorie and her little brother, and the small Jack put his little fat hand into that of big Jack, and led him triumphantly away.

It was a pretty sight to see that congregation gathering on the village green. From the fishermen's cottages there came a stream of people down to the shore,—mothers with babies in their arms and leading young children by the hand, groups of boys and girls wearing shoes and stockings who had been barefooted all the week, many a weather-beaten sailor, many a sunburnt fisher lad, many elderly people too, old men, and white-haired women in closely-plaited white caps. There were visitors, too, coming down from the rocks, and these mostly kept in the background, and had at first an air of watching the movement rather than joining in it. My York friends were, however, well to the front, and the children nodded to me, and smiled at one another as they saw me led like a lamb to the service by my two small guardians.

It was a lovely day, and the sandy ground was dry, and the congregation sat on the rough coarse grass or perched on the sand hillocks round. As for the old boat, it was occupied by the choir, and little Jack, having seen me safely to the spot, climbed into it and stood proudly in the stern. He had a hymn-book in his hand, which I knew he could not read, for he was holding it upside down, but he looked at it as long and as earnestly as if he could understand every word. Marjorie planted herself beside me, I suppose to watch me, in case I showed signs of running away before the service was over.

Then just before eleven, and when quite a large company of people had gathered on the green, her father arrived. He was a man of about forty, and his face gave me the impression that he had known trouble, and yet I fancied as I looked further at him that the trouble, whatever it was, had ended. He seemed to me like one who has come out of a sharp storm, and has anchored in a quiet haven. For whilst I noticed in his face the traces of heavy sorrow, still at the same time he looked happier and more peaceful than any of those who stood round him; in fact, it was the most restful face I had ever seen. He was not an educated man, nor was he what men call a gentleman, and yet there was a refinement about him which made one feel at once that he was no common man, and had no common history. His face was so interesting to me, that I am afraid I was gazing at him instead of finding the hymn he had given out, but I was recalled to my duty by his little daughter, who seized the hymn-book she had given me at the beginning of the service, found the page for me, and pointed with her small finger to the place.

It was a mission hymn, sung to a wild, irregular tune. I daresay I should have smiled if I had heard it anywhere else, but it was no laughing matter that morning. As I looked at the brown fishermen who had taken off their oilskin caps, as I glanced at the earnest face of the preacher, as I noticed how even children, like little Marjorie beside me, were singing with all their heart and soul the simple plaintive words, I felt strangely solemnized.

Then came the prayer, and I felt as he prayed that One whom we could not see was standing amongst us. It was a very simple prayer, but it was the outpouring of his heart to God, and many a low Amen broke from the lips of the fishermen as their hearts went with his.

The sermon followed. Shall I call it a sermon? It was more an appeal than a sermon, or even an address. There was no attempt at style, there were no long words or stilted sentences; it was exactly what his prayer had been, words spoken out of the abundance of his earnest heart. The prayer had contained the outpouring of his soul to his God in heaven; the words, to which we listened afterwards contained the outpouring of his soul to us, his brothers and sisters on earth.

There was a great hush over the congregation whilst he spoke. The mothers quieted their babes, the children sat with their eyes fixed on the speaker; even those visitors who had been on the outskirts of the crowd drew near to listen.

'What are you, dear friends?' he began; 'that is our subject to-day. What are you? How many different answers I hear you make, as you answer my question in your hearts!'

'What am I?' you say. 'I am a fisherman, a strong active man, accustomed to toil and danger.' 'I am a mother, with a large family of little ones, working hard from morning till night.' 'I am a schoolboy, learning the lessons which are to fit me to make my way in the world.' 'I am a busy merchant, toiling hard to make money, and obliged to come to this quiet place to recruit my wearied energies.' 'I am an artist, with great ambition of future success.' 'I am an old man, who has weathered many a storm, but my work is done now; I am too old to fish, too tired to toil.' 'I am a gentleman of no occupation, idling comfortably through a busy world.' 'I'—and here he glanced at his own little Jack in the stern of the old boat—'I am a tiny child, with an unknown life all before me.'

'Dear friends, such are some of your answers to my question. Can I find, do you think, one answer, one description, which will suit you all—fishermen, mothers, boys and girls, artists, merchants, gentlemen, the old man and the little child? Yes, I can. If I could hand you each a piece of paper and a pencil this day, there is one description of yourself which each of you might write, one occupation which would include you all, the old, the young, the rich and the poor. Each of you, without exception, might write this—I am a servant.

'I, the speaker, am a servant; you who listen, all of you, are servants.'

'Well, I don't know how he is going to make that out,' I said to myself. 'I thought he was going to say we were all sinners, and that, I suppose, we are, but servants! I do not believe I am anybody's servant.'

'All servants,' he went on, 'but not all in the same service. As God and the angels look down upon this green to-day they see gathering together a great company of servants, but they also see that we are not all servants of the same master. They see what we do not see, a dividing line between us. On one side of the line God sees, and the angels see, one company of servants—and in God's book He gives us the name of their master—Servants of sin.

'On the other side of the line, God sees, and the angels see, another company of servants—Servants of Christ.

'Which company do you belong to, dear friend? You fishermen on the bank there, what are you? Little child, what are you?—a servant of sin, or a servant of Jesus Christ?

So I tried to turn it off from myself, and to forget the words which had been spoken. And whenever the question came back to me, the question which the speaker had repeated so often, 'What are you?' I answered it by saying to myself, 'I am a poor artist, having a holiday in Runswick Bay, and I am not going to trouble my head with gloomy thoughts.'

Polly had prepared an excellent dinner in honour of the day, and I did full justice to it. Then I determined to walk to Staithes, and to spend the rest of the day in seeing the country. I had always been accustomed, to paint on Sunday, but only one of the artists seemed to be at work, and Duncan and Polly had been so much shocked by seeing him, that I did not venture to do the same. I enjoyed the walk along the cliffs, and came back in good spirits, having completely shaken off, as I imagined, the remembrance of the speaker's words.

'I've got a big favour to ask of you, sir,' said Duncan the next day. 'You'll not think I'm taking a liberty, will you?'

'Certainly not, Duncan,' I said. 'What do you want?'

'Well, it's just here, sir—me and my mates, we get up some sports every year on the green. We have 'em in August, sir, just when the visitors are here. They all turn out to see them, and there's lots of them is very good in subscribing to the prizes. You see, sir, there is a many young fellows here, young chaps who must have something to keep them out of mischief; when they're not fishing, they're bound to be after the beer, if they haven't something to turn their minds and keep them going a bit. And these sports, why, they like 'em, sir; and a man must keep sober if he's to win a prize—you understand, sir?'

'Yes, Duncan, I understand,' I said; 'it's first-rate for these young lads, and for the old lads too, for the matter of that. I suppose you want a subscription for your prizes?' I added, as I handed him half a sovereign.

'Thank ye kindly, sir, I won't refuse it, and it's very good of you to help us so largely; but that isn't what I came to ask of you. I hardly like to bother you, sir,' he said doubtfully.

'Never mind the bother, Duncan; let's hear what you want.'

'Well, it's just here, sir. Could you, do you think, make for us some sort of a programme to hang up by the post office there, for visitors to see? You draw them pictures so quick, sir, and—'

'I see, Duncan; you want the programme to be illustrated. I'm your man; I'll do it at once.' I was really only too glad to oblige the dear, honest fellow.

He was wonderfully pleased at my ready consent, and went off at once to procure a board upon which my programme might be fastened. We soon made out together a list of attractions, and I had great pleasure in beautifying and illustrating the catalogue of sports.

I headed it thus:—

OYEZ, OYEZ! RUNSWICK ATHLETIC SPORTS.

Then, from the R of Runswick I hung a long fishing net, covered with floats, and falling down over a fish basket, and some lobster-pots, whilst on the ground were lying a number of fish which had been emptied out of the basket.

Next followed a list of patrons, such as: The Honourable O'Mackerell, Lord Crabby Lobster, Sir C. Shrimp, etc., etc.

Then came a list of the various sports, each profusely illustrated—The tug of war, the jockey race, the women's egg and spoon race, the sack race, the greasy pole, the long jump, etc.; and lastly, an announcement of a grand concert to be held in the evening, as a conclusion of the festivities of the day.

Duncan was more than satisfied—he was delighted, and his gratitude knew no bounds. His excitement, as he carried the board away to hang it in a conspicuous place, was like the excitement of a child.

The whole village seemed to be stirred as the eventful day drew near.

'Are you going to see the great tug, big Mr. Jack?' my little friend called to me over the wall as I was painting. As for the York boys, Harry and Bob, they spent a great part of every day in admiring the programme, and in bringing other visitors to see and admire the work of their artist.

How anxiously Duncan watched the sky the day before the sports, and how triumphantly Polly announced, when I came down to breakfast, 'A fine day, sir; couldn't be finer, could it now?'

Those village sports were really a pretty sight. I see it all in my mind's eye now. I often wonder I have not made a picture of it. The high cliff stretching overhead, and covered with bushes and bracken, amongst which nestled the red-tiled cottages. Then below the cliff the level green, covered with strong, hardy fishermen and their sunburnt wives, and surrounding the green, on the sand-hills, the visitors old and young, dressed in bright colours and holiday attire. Is it too late to paint it from memory, I wonder? I see it all still so distinctly.

The sports lasted a long time, and went off well. Polly distinguished herself by winning the egg and spoon race, much to the joy of little John, who watched all the proceedings from his father's arms.

Then came the greatest event of all, the tug of war. A long cable was brought out and stretched across the green, and a pocket-handkerchief was tied in the centre of it. Two stakes were then driven into the ground, and between these a line was chalked on the grass. The handkerchief was then placed exactly over the line. After this all the fishermen who entered the lists were divided into two parties. Then each side laid hold of one end of the rope, and at a given signal they began to pull. It was a trial of strength; whichever side could draw the handkerchief past the two stakes and over the line, that side would win.

How tremendously those men pulled! What force they put into it! Yet for a long time the rope did not move a single inch. All the strength of those powerful fishermen was put out; they were lying on the ground, that their pull might be all the stronger. Every sinew, every nerve, every muscle seemed to be on the strain, but so evenly were the two sides matched, that the rope was motionless, and it seemed impossible to tell which party would win.

Little John was eagerly watching his father.

'Pull, daddy, pull!' I heard him cry; and I think I was nearly as pleased as he and Polly were when Duncan and the mates on his side suddenly made one mighty effort, and the handkerchief was drawn across the line. There was tremendous cheering after this. Polly clapped her hands with delight, and little Jack and big Jack nearly shouted themselves hoarse.

It was an interesting sight, and I had reason to remember it afterwards, as you will see. The evening concert went off as well as the sports had done, and Duncan came in at night rather tired, but well satisfied with the day's proceedings.

I enjoyed all the sights at Runswick Bay, but I think I was particularly charmed with what happened on the day after the sports. All the village was early astir, and as I was dressing, it seemed to me that every fisherman in the place was hurrying down to the beach. It was not long before I followed them to see what they were doing. I found that they were about to draw the crab-boats up from the shore, to a place where they would be safe from the winter storms. It was hard work, but every one was there to give a hand. A long string of men and lads laid hold of the strong cable fastened to the boat. Even the wives and elder children caught hold of it. I myself went to their help, and several of the visitors followed my example. Then, when we were all in position, there came a pause, for Duncan, who was directing the proceedings, charged us not to pull till the signal was given. Then there rose a peculiar cry or yodel, all the fishermen uttering it together, and as soon as it ceased we gave our united, mighty pull. Then we paused to take breath, until once more there came a yodel followed by another pull, and as this was repeated again and again, it was grand to see the heavy boat making steady and regular progress. Across the heavy sand she came, up the low bank, over the rough grass, slowly, steadily, surely, she moved onward, until at length she was placed in safety, far out of reach of the highest tide and the strongest sea. Thus, one after another, the boats were drawn up, and we were fairly tired before our work was done.

I think it must have been that very day, that, as I was sitting painting, I once more heard the broken notes of the instrument which had troubled me so much before. It was that tune again, my mother's tune, and somehow, I do not know how it was, with the sound of my mother's tune there came back to my mind the remembrance of the Sunday service. Ah! my mother was on the right side of the line, I said to myself; she was a servant of Christ. But her son! what is he?

I did not want to follow out this subject, so I jumped up from my camp-stool, and standing under the wall, I called, 'Little Jack, little Jack.'

The music stopped at once, and the child came out. Dear, little merry fellow, how fond I was of him already!

'Yes, Mr. big Jack,' he said, as he ran out of the gate.

'Come and talk to me, old chappie,' I said, 'whilst I paint. Who plays music in your house?'

'I do,' said little Jack.

'You do, Jack? Why, you are a funny little fellow to play music! What do you play on, and who taught you?'

'Nobody teached me, Mr. Jack,' he said; 'I teached my own self.'

'Teached your own self? Why, how did you manage that?' I asked.

'I turned him round and round and round, Mr. Jack, and the music came, and I teached my own self,' he repeated.

'What is it, Jack?' I asked. 'Is it an old musical box?'

'No, it's an organ, a barrow-organ, Mr. Jack.'

'Oh, a barrel-organ you mean, little chappie; why, however in the world did you get hold of a barrel-organ? Is it a little toy one?'

'No, it's big, ever so big,' he said, stretching out his hands to show me its size.

'Why, whoever gave you it?' I asked.

'It isn't Jack's own organ,' said the child.

'Whose is it, then?'

'It's father's, father's own organ.'

It seemed to me a most extraordinary thing for the mission preacher of Runswick Bay to have in his possession, but I did not like to ask any more questions at that time.

However, in the afternoon my little friend called to me over, the wall, 'Big Mr. Jack, come here.'

'Come where, my little man?'

'Come inside and look at father's organ; I'll play it to you, Mr. Jack.'

'What will father say if I come in?'

'Father's out.'

'What will mother say?'

'Mother's out too.'

I did not much relish the idea of entering a man's house in his absence, but such plaintive entreaties came from the other side of the wall. Over and over again he pleaded, 'Do come, Mr. Jack; do come quick, Mr. Jack!' that at last, to please the child, I left my work for a few minutes and went up the steps which led to the gate of their garden.

It was only a small place, but very prettily laid out. There was a tiny lawn, well kept, and covered with short, soft grass, and in the centre of this a round bed filled with geraniums, calceolarias, and lobelias. Round the lawn, at the edge of the garden, was a border, in which grew all manner of gay and sweet-smelling flowers. There were asters and mignonette, sweet-peas and convolvolus, heliotrope and fuchsias. Then in front of me was the pretty cottage, with two gables and a red-tiled roof, the walls of which were covered from top to bottom with creeping plants. Ivy and jessamine, climbing roses, virginia-creeper, and canariensis, all helped to make the little place beautiful.

'What a pretty home you have, little Jack!' I said.

He kept tight hold of my hand, lest I should escape from him, and led me on—into a tiny entrance hall, past one or two doors, down a dark passage, and into a room at the back.

This room had a small bow-window overlooking the sea, the walls were covered with bookshelves, a writing-table stood in the window, and in the corner by the fireplace was the extraordinary object I had been brought to see—an extremely ancient and antiquated barrel-organ.

What a peculiar thing to come across in a preacher's study! What possible use could he have for it? It was a most dilapidated old instrument, almost falling to pieces with old age. The shape was so old-fashioned that I do not remember ever having seen one like it; the silk, which had doubtless once been its adornment, was torn into shreds, and it was impossible to tell what its original colour had been; the wood was worm-eaten and decayed, and the leg upon which it had rested could no longer support its weight.

'Let me hear you play it, Jack,' I said.

He sat down with great pride to turn the handle, but I noticed that half the notes were broken off the barrel, which accounted for only fragments of each tune being heard, whilst many bars of some were wanting altogether. However, Jack seemed very proud of his performance, and insisted on my staying till he had gone through the whole of the four tunes which the poor old thing was supposed to play. He announced their names, one by one, as each began.

'This is "My Poor Mary Anne," Mr. Jack, very sad.' Then when that was finished, 'This is the Old Hundred, very old.'

After this there was a long turning of the handle without any sound being heard, for the first part of the next tune was gone entirely. 'I can't say the name of this one, Mr. Jack,' he explained; 'Marjorie calls its something like "Ma says."'

'Oh! the "Marseillaise,"' I said, laughing; 'all right, little man, I know that.'

'Then comes father's tune, father does like it so. Listen, "Home, sweet home, there's no place like home, there's no place like home." Do you like it, Mr. Jack?'

'Yes, I do like it, Jack,' I said; 'I knew it when I was a little chap like you.'

As he played, once more it brought before me my mother's voice and my mother's words. I had not thought of my mother for years so much as I had done at Runswick Bay. Even the old organ brought her back to me, for she was always kind to organ-grinders. There was an Italian who used to come round with a barrel-organ when I was a little boy. I can see him now. I used to watch for him from my nursery window, and as soon as he came in sight I flew down to my mother for a penny, and then went into the garden and stood beside him whilst he played. My mother gave me a musical-box on my birthday; it was in the shape of a barrel-organ, and had a strap which I could hang round my neck. I used to take this box with me, and standing beside the Italian, I imitated his every movement, holding my little organ just as he held his big one, and playing beside him as long as he remained. So delightful did this man's occupation seem to me, that I can remember quite well when my father asked me one day what I would like to be when I was a man, I answered without a moment's hesitation, 'An organ-grinder, of course, father.'

Those old boyish days, how long ago they seemed! What was the use of recalling them? It would not bring back the mother I had lost, or the father who had cared for me, and it only made me depressed to think of them. What good, I asked myself, would my holiday do me if I spent it in brooding over bygone sorrow? I must forget all this kind of thing, and cheer up, and get back my spirits again.

'Now, little Jack,' I said, 'big Jack must go back to his picture; come and climb into the old boat, and I'll see how you would do in the foreground of it.' He looked such a merry little rogue, perched amongst the nets and fishing tackle, that I felt I should improve my picture by introducing him into it, and therefore from that day he came for a certain time every morning to be painted. He was such a good little fellow, he never moved a limb after I told him I was ready, and never spoke unless I spoke to him. A more lovable child I never saw, nor a more obedient one. With all his fun, and in spite of his flow of spirits, he was checked in a moment by a single word. No one could be dull in his company, and as the week passed on I began to regain my usual cheerfulness, and to lose the uncomfortable impression left on my mind by the sermon on the shore and the questions the preacher had asked us.

I had quite made up my mind not to attend the service on the following Sunday, and when a pink paper floated down on my easel on the Saturday morning, I caught it and thrust it into my pocket, without even looking to see what the subject was to be.

'Have you got it, Mr. Jack?' said the child's voice above me.

'All right, little man,' I answered; 'it's all safe and sound.'

I made my plans for Sunday with great care. I asked for an early breakfast, so that I might walk over to Kettleness, a place about two miles off along the coast, and which could only be reached at low tide; and when I was once there, on the other side of the bay, I determined to be in no hurry to return, but to arrive at Runswick too late for the service on the sands. If Duncan and Polly missed me, they would simply conclude that I had found the walk longer than I had expected.

But, as I was just ready to set out for Kettleness, a tremendous shower came on.

'You'll never set off in this weather, sir?' said Duncan anxiously.

'Oh no, of course not,' I answered lightly.

I fancied that he looked more concerned than the occasion warranted, and I feared that he suspected the real reason for my early walk.

There was now nothing to be done but to wait till the shower was over, and by that time I found it would be impossible for me to go to Kettleness without seeming deliberately to avoid the service.

The sun came out, and the sky was quite blue before eleven o'clock, and the fishermen spread tarpaulins on the sand for the congregation to sit on, and I found myself—I must say very much against my will—being led to the place by little Jack.

'Well, there is no need for me to listen,' I said to myself; 'I will plan out a new picture, and no one will know where my thoughts are.'

But, in spite of my resolution to the contrary, from the moment that Jack's father began to speak, my attention was riveted, and I could not choose but listen.

'The Tug of War is our subject to-day, dear friends,' he began, 'and a very suitable subject, I think, after what we have witnessed on this green during the past week. We have seen, have we not, a long pull, a strong pull, and a pull all together, as yon heavy crab boat was dragged up from the beach? How well she came, what progress she made! with each yoddel we brought her farther from the sea. We all of us gave a helping hand; fishermen, wives, visitors, friends, all laid hold, and all pulled, and the work, hard as it seemed, was soon accomplished. Why? Because we were all united. It was a long pull, a strong pull, and a pull all together.

'And now let me bring back to your memory another event during this past week. The place is the same, our village green, the same rope is used, and those who pull are the very same men, strong, brawny, powerful fishermen. Yes, you pulled your very hardest; if possible you put forth more strength than when the crab boat was drawn up, and yet, strange to say, there was no result, the rope did not move an inch. What were you pulling? What was the mighty weight that you had to move? What was it that, for such a long time, baffled the strength of the strongest among you? The weight you could not move was not a heavy boat, but a light handkerchief!

'Why was there this difference? Why was the handkerchief harder to move than the boat? The answer to that question was to be found at the other end of the green. There were other pullers at the rope that day, pulling with all their might in an exactly opposite direction. It was not a united pull, and therefore for a long time there was no result, and we watched on, until at length one side was proved the strongest, and the handkerchief was drawn by them triumphantly across the line.

'To-day, dear friends, I speak to you of yet another tug of war. The place is the same, Runswick Bay and our village green, but the weight to be drawn is not a boat, not a handkerchief; the weight is a human soul. It is your soul, my friend, your immortal soul; you are the one who is being drawn.

'And who are the pullers? Oh, how many they are! I myself have my hands on the rope. God only knows how hard I am pulling, striving with all my might, if possible to draw you, my friend, to Christ. But there are other hands on the rope besides mine. Your conscience pulls, your good old mother pulls, your little child pulls, your Christian mate pulls; each sermon you hear, each Bible class you attend, each hymn you sing, each prayer uttered in your presence, each striving of the Spirit, each God-given yearning after better things, each storm you come through, each danger you escape, each sickness in your family, each death in your home, each deliverance granted you, gives you a pull God-ward, Christ-ward, heaven-ward.

'Yet, oh, my dear friend, you know, as clearly as you know that you are sitting there, that, so far, Christ's pullers are drawing in vain. You have never yet, you know it, crossed the line which divides the saved from the unsaved. Why is this? Why, oh, why are you so hard to move?

'Oh, my friend, do you ask why? Surely you know the reason! Is it not because there are other hands on the rope, other pullers drawing in an exactly opposite direction? For Satan has many an agent, many a servant, and he sends forth a great army of soul-pullers. Each worldly friend, each desire of your evil nature, each temptation to sin, each longing after wealth, each sinful suggestion, gives you a pull, and a pull the wrong way, away from safety, away from Christ, away from God, away from heaven, away from Home. And towards what? Oh, dear friend, towards what? What are the depths, the fearful depths towards which you are being drawn?'

He said a good deal more, but I did not hear it. That question seemed burnt in with a red-hot iron into my soul. What are the depths, the fearful depths into which you are being drawn? I could not shake it off. I wished I could get away from the green, but Jack had brought me close to the boat where the choir stood, and there was no escape. I should have to sit it out; it would soon be over, I said to myself.

The service ended with a hymn. Another of their queer, wild, irregular tunes, I thought; I was not going to sing it. But when Jack saw that I did not open my book, he leant over the side of the boat, and poked my head with his hymn-book. 'Sing, big Mr. Jack, sing,' he said aloud, and then, for very shame, I had to find my place and begin. I can still remember the first verse of that hymn, and I think I can recall the tune to which they sang it:—

'Oh, tender and sweet was the Master's voice,

As he lovingly called to me:

"Come over the line! it is only a step—

I am waiting, My child, for thee!"

"Over the line!" Hear the sweet refrain!

Angels are chanting the heavenly strain!

"Over the line!" Why should I remain

With a step between me and Jesus?'

I was heartily glad when the service was over, and I went on the shore at once, to try to walk the sermon away. But I was not so successful as I had been the Sunday before. That question followed me; the very waves seemed to be repeating it. What are the depths, the fearful depths, to which you are being drawn? I had not looked at it in that light before. I had been quite willing to own that I was not religious, that I was leading a gay, easy-going kind of life, that my Sundays were spent in bed, or in novel reading, or in rowing, or in some other amusement. I was well aware that I looked at these things very differently from what my mother had done, and I had even wondered sometimes, whether, if she had been spared to me, I should have been a better fellow than I knew myself to be. But as for feeling any real alarm or anxiety with regard to my condition, such a thought had never for one moment crossed my mind.

Yet if this man was right, there was real danger in my position. I was not remaining stationary, as I had thought, but I was being drawn by unseen forces towards something worse, towards the depths, the fearful depths, of which he had spoken.

At times I wished I had never come to Runswick Bay to be made so uncomfortable; at other times I wondered if I had been brought there on purpose to hear those words.

I went back to dinner, but I could not enjoy it, much to Polly's distress. The rain fell fast all the afternoon, and as I lay on my bed upstairs I heard Polly washing up, and singing as she did so the hymn we had had at the service—

'Come over the line to Me.'

There seemed no chance of forgetting the words which had made me so uneasy.

That night I had a strange dream. I thought I was once more on the village green. It was a wild, stormy night, the wind was blowing hard, and the rain was falling fast; yet through the darkness I could distinguish crowds of figures gathered on the green. On the side farther from the sea there was a bright light streaming through the darkness. I wondered in my dream what was going on, and I found that it was a tug of war, taking place in the darkness of the night. I saw the huge cable, and gradually as I watched I caught sight of those who were pulling. I walked to the side from which the light streamed, and there I saw a number of holy and beautiful angels with their hands on the rope, and amongst them I distinctly caught sight of my mother. She seemed to be dragging with all her might, and there was such an earnest, pleading, beseeching expression on her dear face that it went to my very heart to look at her. I noticed that close beside her was the preacher, little Jack's father, and behind him was Duncan. They were all intent on their work, and took no notice of me, so I walked to the other end of the green, the one nearest the sea, that I might see who were there. It was very dark at that end of the rope, but I could dimly see evil faces, and dark, strange forms, such as I could not describe. Those on this side seemed to be having it much their own way, I thought, for the weight, whatever it was, was gradually drawing near to the sea; and, lo and behold, I saw that they were close upon a terrible place, for mighty cliffs stood above the shore, and they were within a very short distance of a sheer and terrible precipice.

'What are you dragging?' I cried to them.

And a thousand voices seemed to answer, 'A soul! a soul!'

Then, as I watched on, I saw that the precipice was nearly reached, and that both those who pulled and the weight they were dragging were on the point of being hurled over, and suddenly it flashed upon me in my dream that it was my soul for which they were struggling, and I heard the cry of the pullers from the other side of the green, and it seemed to me that, with one voice, they were calling out that terrible question, 'What are the depths, the fearful depths, to which you are being drawn?' And through the streaming light I saw my mother's face, and a look of anguish crossed it, as suddenly the rope broke, and those who were drawing it on the opposite side went over with a crash, dragging my soul over with them.

I woke in a terror, and cried out so loudly that Duncan came running into my room to see what was the matter.

'Nothing, Duncan,' I said, 'I was only dreaming; I thought I had gone over a precipice.'

'No, thank God, you're all safe, sir,' he said. 'Shall I open your window a bit? Maybe the room's close; is it?'

'Thank you, Duncan,' I answered; 'I shall be all right now. I'm so sorry I have waked you.'

'You haven't done that, sir; me and Polly have been up all night with the little lad. He's sort of funny, too, sir, burning hot, and yet he shivers like, and he clings to his daddy; so I've been walking a mile or two with him up and down our chamber floor, and I heard you skriking out, and says Polly, "Run and see what ails him." So you haven't disturbed me, sir, not one little bit, you haven't.'

He left me then, and I tried to sleep, but sleep seemed far from me. I could hear Duncan's footsteps pacing up and down in the next room; I could hear little John's fretful cry; I could hear the rain beating against the casement; I could hear the soughing and whistling of the wind; I could hear Polly's old eight-day clock striking the hours and the half-hours of that long, dismal night; but through it all, and above it all, I could hear the preacher's question, 'What are the depths, the fearful depths, to which you are being drawn?'

I found it impossible to close my eyes again, so I drew up the blind, and, as morning began to dawn, I watched the pitiless rain and longed for day. The footsteps in the next room ceased as the light came on, and I concluded that the weary child was at last asleep. I wished that I was asleep too. I thought how often my mother, when I was a child, must have walked up and down through long weary nights with me. I wondered whether, as she did so, she spent the slow, tedious hours in praying for her boy, and then I wondered how she would have felt, and how she would have borne it, had she known that the child in her arms would grow up to manhood, living for this world and not for the Christ she loved. I wondered if she did know this now, in the far-off land where she dwelt with God.

I think I must have dozed a little after this, for I was suddenly roused by Polly's cheery voice, cheery in spite of her bad night,—

'Have a cup of tea, sir, it'll do you good. You've not slept over well, Duncan says. I'll put it down by your door.'

I jumped out of bed and brought it in, feeling very grateful to Polly, and I drank it before I dressed. That's just like a Yorkshire woman, I thought. My mother came from Yorkshire.

'I think it must have been nightmare I had last night, Polly,' I said as I finished my breakfast, and began to put all in order for my morning's work.

I was at my painting early the next morning, for the sun was shining brightly, and the air was wonderfully clear. My portrait of little Jack sitting in the boat promised to be a great success. As I was hard at work upon it that day, I heard a voice behind me.

'I never thought my little lad would figure in the Royal Academy,' said the voice.

It was the voice of Jack's father—the voice which had moved me so deeply, the voice which had made me tremble, only the day before. Even as he spoke I felt inclined to run away, lest he should ask me again that terrible question which had been ringing in my ears ever since. Even as I talked to him about my picture, and even as he answered in pleasant and friendly tones, through them all and above them all came the words which were burnt in upon my memory: 'What are the depths, the fearful depths, to which you are being drawn?'

'I hope my children are not troublesome to you,' he said.

'Oh no,' I answered; 'I love to have them here, and Jack and I are great friends. Do you know,' I went on, 'he took me into your study the other day? I am afraid I was taking a great liberty; but the little man would hear of no refusal—he wanted me to see the old barrel-organ.'

'What, my dear old organ!' he answered. 'Yes, Jack is nearly as fond of it as his father is.'

'His father?' I replied, for it seemed strange to me that a man of his years should care for what appeared to me scarcely better than a broken toy.

'That organ has a history,' he said, as he noticed my surprise; 'if you knew the history, you would not wonder that I love it. I owe all I am in this world, all I hope to be in the world to come, to that poor old organ. Some day, when you have time to listen, perhaps you may like to hear the story of the organ.'

'Thank you,' I said; 'the sooner the better.'

'Then come and have supper with us to-night. Nellie will be very pleased to see you, and the bairns will be in bed, and we shall have plenty of time and quiet for story-telling.'

I accepted his invitation gratefully, for September had come, and the evenings were growing dark, and my time hung somewhat heavily on my hands. Polly, I think, was not sorry when she heard I was going out, for Duncan was away in the boat fishing, and little John was so feverish and restless that she could not put him down even for a moment.

The cottage looked very bright and pretty when I arrived, and they gave me a most kind welcome. A small fire was burning in the grate, for the evenings were becoming chilly. The bow window was hung with India-muslin curtains, tied up with amber ribbon, the walls were adorned with photographs framed in oak, the supper table was covered with a snowy cloth, and a dainty little meal was laid out with the greatest taste and care, whilst in the centre was a china bowl, containing the leaves of the creeper which covered the house, interspersed with yellow bracken and other beautiful leaves, in every varied shade of their autumn glory. Jack's mother was evidently a woman of taste. She had a quiet, gentle face, almost sad at times when it was at rest; but she had Jack's eyes and Jack's bright smile, which lighted up her face, as a burst of brilliant sunshine will stream suddenly down a dark valley, and make it a perfect avenue of light.

I enjoyed the company of both husband and wife exceedingly, and as we sat round the table and chatted over our supper all feeling of constraint passed away, and I no longer heard the words of that question which had so troubled me all day long. He did not mention the object for which I had come whilst the meal was going on. We talked of Runswick Bay and its surroundings, of the fishermen and their life of danger; we spoke of the children, and of my picture, of my hopes with regard to the Royal Academy, and of many other interesting topics.

Then the cloth was removed, and we drew near the fire. I had just said to him, 'Now for your story,' and he was just beginning to tell it, when, as I sat down in an arm-chair which Nellie had placed for me by the fire, my eye fell upon a photograph which was hanging in a frame close to the fireplace. I started from my seat and looked at it. Surely I could not be mistaken! Surely I knew every feature of it, every fold of the dress, every tiny detail in the face and figure. It was the counterpart of a picture which hung opposite my bed in my London home.

'However on earth did you get that?' I cried. 'Why, it's my mother's picture!'

I think I have never felt more startled than I did at that moment. After all the thoughts of yesterday, after my dream of last night, after all my recollection of my mother's words to me, and her prayers for me—after all this, to see her dear eyes looking at me from the wall of the house of this unknown man, in this remote, out-of-the-world spot, almost frightened me.

I did not realize at first that my host was almost as much startled as I was.

'Your mother!' he repeated; 'your mother! Surely not! Do you mean to tell me,' he said, laying his hand on my arm, 'that your name is Villiers?'

'Of course it is,' I said; 'Jack Villiers.'

'Nellie, Nellie,' he cried, for she had gone upstairs to the children, 'come down at once; who do you think this is, Nellie? You will never guess. It is Jack Villiers, the little Jack you and I used to know so well. Why, do you know,' he said, 'our own little Jack was named after you; he was indeed, and we haven't heard of you for years—never since your dear mother died.'