Geo. H. Heffner

Geo. H. Heffner

by

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1876, by

Geo. H.

Heffner,

In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

It had been fashionable among the ancients, for men of learning to visit distant countries and improve their education by traveling, after they had completed their various courses of study in literary institutions, and the same custom still prevails in Europe at the present time; but in our country, comparatively few avail themselves of this finishing course. It is not strange that this should have been so with a people who are separated from the rest of the world by such wide oceans as we are, which could, up to a comparatively recent period, only have been crossed at a sacrifice of much time and money, and at the risk of loosing either life or health. These difficulties have been greatly reduced by the application of steam-power to navigation, and the time has come when an American can make the tour of Europe with but little more expenditure of time and money than it costs even a native of Europe to do it.

One of my principal objects in writing this book is to encourage others to make similar tours. We would have plenty of books no traveling, if some of them did represent the readers in the humbler spheres of life, but the general impression in America is that no one can see Europe to any satisfaction in less than a year or two and with an outlay of from a thousand to two thousand dollars. This is a great mistake. If one travels for pleasure mainly, it will certainly require a great deal of time and money, but a hard-working student can do much in a few months. Permit me to say, that one will see and experience more in two weeks abroad, than many a learned man in America expects could be seen in a year. I sometimes give the particulars of sights and adventures in detail, that the reader may take an example of my experience, for any tour he may propose to make. The times devoted to different places are given that he may form an estimate of the comparative importance of different places.

Statistics form a leading feature of this work, and these have been gathered and compiled with special reference to the wants of the student. Many an American scholar studies the geography and history of foreign countries at a great disadvantage, because he can not obtain a general idea of the institutions of Europe, unless he reads half a dozen works on the subject. To do this he has not the time. This work gives, in the compass of a single volume, a general idea of all the most striking features of the manners, customs and institutions of the people of some eight different nations speaking as many different languages and dialects.

As the sights that one sees abroad are so radically different from what we are accustomed to see at home, I feel pained whenever I think of describing them to any one. If you would know the nature of my perplexity, then go to Washington and see the stately magnificence of our National Capitol there, and then go and describe what you have seen to one who has never seen a larger building than his village church; or go and see the Centennial Exposition at Philadelphia, and then tell your neighbor who has never seen anything greater than a county fair, how, what he has seen compares with the World's Fair! I too am proud of our country, (not so much for what she now is, but because she promises to become the greatest nation that ever existed), but it must be confessed, that America presents little in the sphere of architecture that bears comparison with the castles, palaces and churches of the Old World. The Capitol at Washington, erected at the cost of twelve and a half millions, the City Hall of Baltimore, perhaps more beautiful but less magnificent, and other edifices that have been erected of late, are structures of which we may justly be proud; but let us take the buildings of the "Centennial Exposition" for a standard and compare them with some of those in Europe. The total expenses incurred in erecting all the exposition buildings, and preparing the grounds, &c., with all the contingent expenses, is less than ten million. But St. Peter's in Rome cost nine times, and the palace and pleasure-garden of Versailles twenty times as much as this! It is safe to assert, that if a young man had but two hundred dollars with six weeks of time at his command, and would spend it in seeing London and Paris, he could never feel sorry for it. Young student go east.

London.

London to Paris.

Paris.

Holland.

The Palatinate, (Die Pfalz).

Switzerland.

Italy.

Rome.

Rome to Brindisi.

Subjects treated in a general way are distinguished by being rendered in italics, in this table of contents.

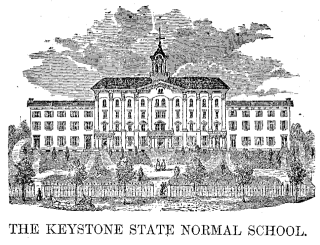

The Keystone State Normal School.

While engaged in making the preliminary arrangements for leaving soon after the "Commencement" of the Keystone State Normal School (coming off June 24th), information was received that the "Manhattan," an old and well-tried steamer of the Guion Line, would sail from New York for Liverpool on the 22nd of June. She had been upon the ocean for nine years, and had acquired the reputation of being "safe but slow." As I esteemed life more precious than time, though either of them once lost can never be recovered, I soon decided to share my fate with her--by her, to be carried safely to the "farther shore," or with her, to seek a watery grave.

The idea of remaining for the Commencement, was at once abandoned; short visits, abrupt farewells, and a hasty preparation for the pilgrimage, were my portion for the few days still left me, and Saturday, the 19th, was determined upon as the day for leaving home. It would be evidence of gross ingratitude to forget the kind wishes, tender good-byes, and many other marks of attention, on the part of friends and acquaintances, which characterized the parting hour. Both Literary Societies had passed resolutions to turn out, and on the ringing of the bell at 6:30 a.m., all assembled in the Chapel, and addresses were delivered.

Half an hour later, we left in procession for the depot, where we arrived in time to exchange our last tokens of remembrance--cards, books, bouquets &c., and shake hands once more.

While the train was moving away, the benedictions and cheers of a hundred familiar voices rang upon the air, and waving handkerchiefs caught the echoes even from the distant cupola of the now fast receding Normal School buildings. A number of torpedoes that had been placed under the wheels of the locomotive, had already apprised us that the train was in motion, and would soon hurry us out of sight. During all this excitement of the parting hour, which seemed to affect some so deeply, I was either looking into the future, or contemplating the present, rather, from an active than from a passive standpoint; and, as a natural consequence, remained quite tranquil and composed--my feelings and emotions being at a lower ebb than they could now be, if the occasion would repeat itself. The idea of making a tour through Europe and to the Orient, had been continually revolving in my mind for many years; and now, that I saw the prospect open of once realizing the happy dreams of my childhood, and the schemes of early youth, I took no time for contemplating the dangers of sea voyages or any of the other perils of adventure.

Before we came to Easton, I formed the acquaintance of a Swiss mother, who seemed much pleased to find one that was about to visit her dear "Fatherland," where she had spent the sunny days of her childhood. After giving me directions and letters of introduction, she entreated me very earnestly to visit her home and kin, and bring them word from her.

New York was reached at 12:10 p.m. As there were but three days remaining for seeing the city, I immediately began my visits to some of its principal points of interest. Having first engaged a room at a hotel in the vicinity of the new Post-Office, I commenced to stroll about, and at 5:30 p.m., entered Trinity Church. Its capacious interior soon disclosed to me numerous architectural peculiarities, such as are characteristic of the English parish churches or of cathedrals in general; and which render old Trinity quite conspicuous among her American sisters. A fee of twelve cents entitled me to an ascent of its lofty spire, which can be made to the height of 304 (?) steps, or about 225 feet.

Sunday, June 20th. Rose at 4:30 a.m. and visited Central Park. This being an importune time for seeing the gay and fashionable life of the city, I contended myself with a walk to the Managerie, and returned in time to attend the forenoon service of Plymouth Church, in Brooklyn. I reached the place before 9:00 o'clock, and formed the acquaintance of a young gentleman who was a great admirer of the Rev. Henry Ward Beecher, and, being an occasional visitor at this church, knew how to get a seat in that congregation, which generally closed its doors against the faces of hundreds, after every available seat was occupied. We at once took our stand at the middle gate, and there endured the pressure of the crowd for more than half an hour before the doors opened. We were the first two that entered, and running up stairs at the head of the dashing throng, succeeded in making sure of a place in the audience. The church has seating capacity for about 2,800 adults. All the pews are rented to members of the congregation by the year, except the outer row of seats along the three walls; but these are generally all occupied in one or several minutes after the doors open.

The choir files in at 10:25. A "voluntary" by the organist at 10:30, and by the choir at 10:32, during which time Mr. Beecher comes in, jerks his hat behind a boquet stand, and takes his seat. Leads in a prayer in so low a strain that he can not be understood at any remote place in the audience. At 10:55 he baptizes eight infants, whose names are passed to him on cards. Concludes another prayer at 11:20 and announces his text, "Christ and him crucified." I Cor. ii. 2

"One of Christ's followers once said, 'If all that Christ said and did were written in books, the world could not contain them. This is an exageration, (a ripple of laughter dances over the congregation), having a great meaning, however." * * * * "David gives us only his intense life." (The audience smile). (11:35). The preacher becoming dramatic in gesticulation and oratorical in delivery, walks back and forth upon the elevated platform. While describing the crosses which he saw yesterday, he becomes highly excited, swinging his arms above his head. "Crosses everywhere. All the way up street; on every beauty's breast." (Explosive laughter). "Some may have cost $500, others possibly $1,500; perhaps some cost $2,000." (Claps his hands in excitement). "Some say 'the church handed down Christianity'; but I say Christianity kept the church alive. What was it, that, in the Reformation, made blood such a sweet manure for souls?" (12:10 p.m.) Pleads earnestly for the weak and the erring. "A man that has gone wrong, and has nobody to be sorry for it is lost; pity may save." Sermon concluded at 12:25. Prayer. Dismissal by singing.

Mr. Beecher's voice is so clear and powerful, that he can be readily understood in the most distant parts of the house. After leaving church, I went up to Columbia Heights, the most aristocratic section of Brooklyn, where I enjoyed myself in contemplating the beautiful and magnificent buildings which constitute the quiet and charming homes of those wealthy people living there. How partial Heaven is to some of her children! Thence I found my way to Greenwood Cemetery, where I spent the remainder of the day amid the tombs and monuments of "the great city of the dead." Guide books containing all the carriage roads and foot-paths of that burial ground, are sold at or near the gate. One of these I procured, and found it was so perfect in the particulars, that I could readily find the grave of any one of the many distinguished persons mentioned in the index, without further assistance whatever. It is impossible here to give an account of the many splendid tombs and monuments erected there by loving hearts and skillful hands, in memory of dear friends and relatives that have "gone away!" What multitudes of strange and curious designs meet the eye here! Some few perhaps seem odd; but most of them bear appropriate emblems, and convey sweet thoughts and tender sentiments in behalf of those "sleeping beneath the sod." What a place for meditation! How quiet, how solemn! No one should visit New York without allotting at least half a day to these holy grounds. How I wander from grave to grave! Here I am struck with the text of an impressive epitaph, and there I see the delicate and elaborate workmanship of a skillful master. Here my heart is touched by the sweet simplicity of a simple slab bearing some touching lines, there I stand in silent admiration before the magnificent proportions of a towering monument, or sit down to study the meaning of some obscure design. A mere sketch of all that I saw there would fill a volume, but I found one monument which I cannot pass by without some notice. It stands on Hilly Ridge, and was erected to the memory of six "lost at sea, on board the steamer 'Arctic,' Sept. 27th, 1854." These words arrested my attention, and a minute later, I had ascended the domical summit of the hill, and stood at the foot of the high monument. It has a square granite base upon which stand four little red pillars of polished Russian granite, supporting a transversely arched canopy, with a high spire. Under the canopy is represented the Ocean and the shipwreck of the "Arctic." The vessel is assailed by a terrible storm, and fiercely tossed upon the foaming waves! She has already sprung a leak, and through the ugly gash admits a copious stream of the fatal liquid, while the raging sea, like an angry monster, is about to swallow her distined prey! Down she goes, and among the many passengers on board, are

Grace, wife of Geo. F. Allen and daughter of James Brown, born Aug. 25th, 1821.

Herbert, infant child of Geo. F. and Grace Allen, born Sept, 28th, 1853.

William B., son of James Brown, born April 23rd, 1825.

Clara, wife of Wm. B. Brown and daughter of Chas. Moulton, born June 30th, 1830.

Clara Alice Jane, daughter of William B. and Clara Brown, born Aug. 30, 1852.

Maria Miller, daughter of James Brown, born Sept. 30th, 1833.

What a sad story! As the ship wreck occurred in the fall, it is highly probable that the party was homeward bound and, had better fortune been with them, might in a very few days have again been safe and happy in their respective homes, relating stories of their strange but pleasant experiences in the Old World. How changed the tale! How their friends must have been looking and waiting for the "Arctic!" One line told the whole story, and perhaps all that was ever heard of them, "The 'Arctic' is wrecked!"

Not far away, on the crown of Locust Hill, sleeps Horace Greeley, America's great journalist and political economist. At the head of his grave stands a temporal memorial stone in the form of a simple marble slab, bearing the inscription, "Horace Greeley, born February 3rd, 1811; died November 29th, 1872." I left the Cemetery at 7:45 p.m., and returned to my quarters in New York.

Monday, June 21st. Having procured passage with the "Manhattan," which was to sail on the morrow, I straightway went to Pier No. 46, North River, to take a look at her! At 12:45 p.m. I stood in the third story of A.T. Stewart's great dry goods establishment, perhaps the largest of kind in the world. It is six stories high, and covers nearly two acres of ground. My next point of destination was Brooklyn Court-House. The afternoon session opened at 2:00 o'clock, but I did not reach the place until half an hour later. The court-room was crowded as usual, and many had been turned away, who stood in knots about the halls and portico, holding the posts, and discussing politics and church matters. I entered hastily, like one behind time and in a hurry, and inquired where the court-room was. "It is crowded to over-flowing, you can not enter," was the reply; but I went for the reporter's door. A few raps, and it was opened. I offered my card and asked for a place in the audience as a reporter. The reply was that the room was already jammed full. But I retained my position in the door all the same! "What paper do you represent?" asked the door-keeper. "I am a correspondent of the National Educator" was my response; whereupon he bid me step in. The court-room was a small one for the occasion, affording seats for about 400 on the floor, and for 125 more in the gallery. Some twenty-five or thirty ladies were scattered through the audience. Mr. Beech, Tilton's senior lawyer, was summing up his closing speech. Tilton and Fullerton sat immediately behind him, but Mr. Beecher was not in court. Toward the close of the session there was a kind of "clash of arms" among the opposing lawyers. Fullerton repeated the challenge previously made by Beech, offering to prove that corrupt influences were made to bear upon the jury. The Judge appointed a time for hearing the complaint, and adjourned the Court.

was visited in the evening, where I saw for the first time on a grand scale, the charming features of the European "cafe" (pronounced cä'fā'). Here are combined the attractions of the pleasure garden or public square, with the ornaments and graces of the ball-room and the opera. It is a magnificent parlor abounding in trees, fountains, statuary and rustic retreats. Gilmore's large band of seventy-five to a hundred pieces, occupying an elevated platform in the centre, render excellent music. Fifteen hundred to two thousand gas jets, eveloped by globes of different colors (red, white, blue, yellow and green) and blazing from the curves of immense arches, spanning the Hippodrome in different directions, illuminate the entire building with the brilliancy of the noon-day sun. To the right of the entrance is an artificial water-fall about thirty feet in height. Two stationary engines supply the water, elevating 1,800 gallons per minute, which issues from beneath the arched roof of a subterranean cavern, and dashing down in broken sheets over a series of cascades and rapids, plunges into a basin below. From this basin it flows away into tanks in an other building, where four to five tons of ice are consumed daily to keep it at a low temperature, so that the vapor and breeze produced by this ice-water, at the foot of the cataract, refreshes the air and keeps it cool and pleasant during the warm summer evenings. The admittance is fifty cents, and 5,000 to 10,000 persons enter every night, during the height of the season. Here meets "youth and beauty," and the wealth, gayety and fashion of New York is well represented,

Tuesday, June 22d. I spent the morning in writing farewell letters, and making the final preparations for leaving. At one o'clock I went on board the "Manhattan," which was still quite empty. In order to have something to do by which to while away the slow dull hours yet remaining, I commenced writing a letter. None of my friends or acquaintances being with me, I bid all my farewells by note. But such writing! Though the vessel was locked to the pier by immense cables, still she was anything but steady. As passengers began to multiply, acquaintances were formed. By and by the stewart came around, and assigned to us our berths. Ship government is monarchic in form. The officers have almost absolute authority, and the passengers, like bashful pupils, do their best to learn the new rules and regulations and adapt their conduct to them, as soon as possible, so that nobody may find occasion for making observations or passing remarks. All these things remind one very much of a first day at school. As

approaches, large numbers of the friends and relatives of some of our passengers, came upon deck to bid good-by. Some cried, others laughed, and many more tried to laugh. Some that seemed to relish repetition, or were carried away by enthusiasm and the excitement of the hour, shook hands over, and over again with the same person. At 3:00 o'clock p.m., the gangway was lowered and the cables were removed. A shock, a boom, and the vessel swung away and glided into the river! The die was cast, and our fate was sealed. Shouts and huzzas rent the air, as the steamer skimmed proudly over the waves, while clouds of handkerchiefs, on deck and upon the receding shore, waved in the air as long as we could see each other. Down, down the river glided the steady "Manhattan," and our thoughts began to run in new channels. "Good-by! dear, sweet America," thought we a hundred times, while we watched the retreating shores; perhaps our thoughts were whispers! Europe with its innumerable attractions, its Alps, Appennines and Vesuvius, its castles, palaces, walled towns, fine cities, great battle fields, ancient ruins and a thousand other milestones of civilization, lay before us; but a wide Ocean, and all the dangers and perils of a long sea voyage lay between us and that other--longed for shore.

The question whether we would ever realize the pleasure of a visit to the Old World, was now reduced to the alternatives of success, or failure by accident or disease.

I had labored under the erroneous impression that sea-sickness was bred of fear and terror, and would attack only women (of both sexes) and children of tender minds and frail constitutions. But, when the waves commenced to roll higher, and the ship began a ceaseless rocking, which was in direct opposition to the wants and comfort of my system, as all manner of swinging ever was, I began to have fears that it was not fright, but swinging, that made people sick at sea. The inner man threatened to rebel, and I made my calculations how much higher the billows might swell, before stomachs would be apt to revolt. We sailed out of sight of the land before dusk, by which time, however, numbers of ill-mannered stomachs had given evidence of their bad humor. Though I nodded but once or twice to old Neptune, during the entire voyage, still I suffered much during the first five days, from the pressure of intense dizziness and headache, occasioned by the incessant rocking of our vessel upon the restless waves. We had a very fine passage, as the sailors would say, but it was far from being as fine as I had always fancied fine sea voyages would be. The rocking of the ship would never be less than about two feet up and down in its width of thirty feet. When the winds blew hard and the waves rolled high, it swung some, twenty or twenty-five feet up and down at its bow and at the stern. The highest waves that we saw in our outward passage were probably from twelve to eighteen feet. That the rocking or swinging of the ship, is the one and only cause of sea-sickness, may admit of a question; but that it is the principal cause, there can be little doubt. My observations and experiences in five or six voyages (long and short) did not point to any other cause. As the sea air is generally regarded as more salubrious and healthier than that on land, it can certainly not be a cause of sea-sickness. Fright and terror, in a timid person might perhaps aggravate the disease in few instances, though it seems doubtful, to say the least. When the sea is calm and smooth, everybody feels well, even if the vessel swims in the middle of the Ocean; but let a storm come on, and the number of sick will increase in proportion to its violence.

On the second day of our voyage, in the afternoon at about 4:00 o'clock, we came across a shoal of whales. There must have been two or three dozen of them. They apparently avoided our ship, as only a few made their appearance very close by, though we sailed through the midst of them. They swam about leisurely near the surface, betraying their whereabouts frequently by spouting; but occasionally they would rise considerably above the surface of the water, and expose large portions of their bodies to our view. The excitement occasioned among all on board, by the appearance of so many of these terrible monsters, greatly quickened our dull spirits, and tended much to alleviate the lonesomeness occasioned by the monotony of the sea voyage.

No one who has never experienced it, can form an idea of how the mind is depressed and benumbed by the monotony of sea life. The nights drag along so slowly, and the days--they seem to have no end. One will often loose his "bearings" so completely, that he knows neither what day of the week it is, nor whether it is forenoon or afternoon. Without keeping a diary or record of some kind, it would be difficult for many to keep a sure run of the date. Ordinarily, one sits down early in the morning to wait for the evening to draw by, and often it happens, when it seems to him that he has waited the length of three days on the land, he is mortified by the announcement that it is yet far from being noon! An eternal present seems to swallow up both the past and the future. After a week or two of such weary waiting, one feels as if he had forgotten almost every thing that happened before the day of his leaving home. I remarked one day to a company of passengers on deck, that I could scarcely recall any thing that had happened in the past; indeed, it required quite an effort to remember that I had ever been in America, or anywhere else except on the old "Manhattan" in an everlasting voyage. "Yes," observed one of the company, "and I heard a fellow say yesterday that time seemed so long to him, that he had really forgotten how many children he had." There is little doubt, that if a ship-load of passengers could be suddenly and unexpectedly landed upon the grassy slope of a verdant hillside; many would under momentary impulse of overwhelming pleasure, kiss the dear earth, as Columbus did on landing at San Salvador, if, indeed, extreme joy did not impel them to make themselves ridiculous by imitating old Nebuchadnezzar, in commencing to graze on the herbage! But the longest day must have an end, and so have sea voyages.

On Saturday morning, July 3rd, everybody came upon deck in hope of seeing land. A report was soon circulated, that the sailors with their telescopes, had already seen the mountains of Ireland. Those passengers that had telescopes or opera glasses soon brought them upon deck. Some said they saw the land, but others using the same glasees could see nothing. This, created a pleasant excitement with but little satisfaction, however, except a lively hope of soon seeing terra firma again. At about 8:00 o'clock (4:00 o'clock Penna. time) it was believed by the passengers generally, that land was really in sight. When I first saw the outline of the mountains through the mist and clouds that hung near the horizon, it stood out so clear and bold that I felt surprised at not having been able to see it long before, as some others had. There were some who could not see the land till an hour afterwards. The inexperienced must first learn, before they will know how to see land. The first light-house (one sixty miles from Queenstown) came into view at 9:35 a.m. We passed it at 10:00 o'clock.

White sea-gulls come one or two days' journey into the sea to meet the ships, and follow them for food. These had been increasing from an early hour, and amounted to about fifty in number in the afternoon. It seems as if their wings would never tire. All-day long they fly after the ships, sometimes even coming over the deck near the passengers.

A great excitement prevailed on board during the whole day, because a number of our passengers were to leave us there. While these were getting ready to depart, and bidding good-by to their many friends on board, many of us were busy writing letters to our friends and relatives in America. Those letters were taken on to Queenstown, there mailed, and brought the first news of our safe passage across the Atlantic. We were still a day from Liverpool, but it was a day of pleasure. The dangers of the deep were now forgotten, the strong winds of the Ocean had abated, and health and happiness over all on board prevailed. Our course continued along.

At about 4:00 o'clock p.m., the little steamer "Lord Lyons" came up to our ship to fetch the passengers that were bound for Queenstown. A company of fruit-women came on board with gooseberries, raspberries and many other good things with which they fed our famished passengers. These were our first fruits of the season, and were highly relished by all.

The vegetation of Ireland is remarkable for its fresh, green color. We all agreed that we had never seen such a rich green color before. "Emerald Isle" (the green island) is a very appropriate name for Ireland, We saw many light-houses and beautiful castles hanging upon the rocky shores or standing proudly upon commanding eminences. Steamers keep so close to the shore in sailing from Queenstown to Liverpool, that the land is nearly always in sight. On Sunday morning, July 4th, the charming fields of Ireland had been exchanged for the lofty mountains of Wales. We passed Holyhead at 9:00 o'clock, and Liverpool came into sight at 1:30 p.m. An hour later we came so near to the coast that the individual trees of a shady wood upon the shores could readily he discerned. By 3:25 we had entered the Mersey, and "half-speed" was ordered. Five minutes later, we anchored and were touched by a tender. Here we learned what custom-house officers are for. Every trunk, carpet-bag and satchel had to be opened for them, and their busy hands were run all through our wardrobes. In order to detect any smuggling that might be attempted, they will examine every trunk or chest, &c., from top to bottom. They did not search our pockets, however, but short of that they are required to do most anything disagreeable to the traveler. As it was Sunday, all the shipping was tessellated with the colors of every nation. It is a grand sight to see acres upon acres of ships so profusely decorated with flags that it seems as if the sky was ablaze with their brilliant colors. Our own "Manhattan" sailed proudly into port with twenty-six flags streaming from her mast-head and rigging.

After we had passed muster, we passed over a kind of bridge or gangway from the "Manhattan" into a little steamer that had come down the river to fetch us. How glad we were to leave the good old ship, and bound into the arms of another that promised to take us ashore in a very few minutes! It was a glorious time! We had come to regard the "Manhattan" as a prison-house, from which we had long desired to take our leave, if we only could. But now that the parting hour had come, how changed our feelings! As the little boat sailed away, we felt sorry to leave her, and commenced to call her by pet names. "Good-by dear 'Manhattan,' many thanks to you for carrying us so safely across the deep wide sea," cried many of us; while others gave the customary three cheers and waved their hats. Though we left her empty behind--no friends, and no acquaintances remaining there, still we continued to wave our handkerchiefs at her so long as we could see her, and have ever since remembered her as the noblest of all the ships that was in harbor that day. Her, colors seemed the brightest, and a hundred happy passengers separated that hour that will never cease to sing her praises. Permit me, kind reader, to add one line more, and in that line make mention of

You may not be able to understand it, or to appreciate how a small party of our passengers came to regard her as almost a sacred thing, but there are a few that know the spell, and who will ever bless the page that tells the tale! Thither we went when the winds blew harder and the waves rolled higher, when our heads became heavier and our steps unsteady! She hung at or near the center of the ship, where there was the least rocking or swinging of all places in the whole vessel. During day-time we lay down beneath her shade, and at night, we would sit by her side relating to each other our feelings and experiences, &c. When sea-sickness had left our company, we agreed upon that place as our general rendezvous by day and by night, for the remainder of the voyage. There we spent our days and there we met every night! If our sleep was interrupted by a storm at the midnight hour, thither would we go for relief! A thousand recollections gather around that boat, and bind our hearts together there, as with so many cords; because our hearts meet there in fond remembrance, therefore will we never forget the place.

I had bid adieu to all my acquaintances before leaving the steamer, and consequently went ashore quite by myself. I did not experience that piercing thrill through my system as I had expected to, on touching the firm earth again; for we had seen the shore so long before we could land, that all its novelty had disappeared.

Traveling-bag in hand, which contained my entire wardrobe, I now went In search of an hotel. The "Angel Hotel" was soon pointed out to me, and on entering it, I learned that several of my fellow-passengers had already taken rooms there. It is entirely under the control of ladies, being managed by a proprietress and female clerks. The house is an excellent one, and the accommodations are first-class. It bears a very appropriate name. After partaking of a hardy supper, I walked out to "take a look at Europe!" At 6:45 p.m., I entered St. Peter's Church, and was conducted to a pew. Here, as elsewhere in Europe, the young and the old of both sexes occupy the same seat together. One of the little boys of the family occupying the same pew with me, gave me a hymn-book. A part of the exercises consisted in chanting psalms. The eagle lectant and the Bible characters represented in the stained glass of the windows, soon enlisted my attention, but the meaning of having two birds perched upon a high stand in the middle of the church, I could not unfold, nor was there any one about that could tell me. The next day I saw the same bird beside a noble female form in the museum. "What bird is that?" said I to a by-stander. "That figure," said he, "is the emblem of Liverpool, and the bird is the liver, which abounded down in the pools, and after which the place was first named."

St. Luke's was visited after service. The chorister seemed much pleased to meet an American, and showed me every mark of attention. When asked whether all the churches of Liverpool had their chancels in the east ends, he answered in the affirmative. I afterwards found this to be true all over Europe. The dead are buried everywhere so as to face the rising sun.

Around St. John's the memorial slabs lie flat upon the graves. IHS, with a cross over the H, is engraved upon the tombstones of the Catholics. These same letters IHS equivalent to JES or JESUS, are to be seen, in almost every church and chapel in all Christian Europe. Upon goblets, chrismatories and crosses in the churches they are generally written in gold; while myriads of crosses on headstones in the graveyards bear the same mystical letters. Various other interpretations are given to them by different writers, but every explanation except the one above given, seems far-fetched and of doubtful origin, to say the least.

In summer, the sun sets after 8:00 o'clock in the latitude of Liverpool. I saw some twilight after 10:00 o'clock. The early dawn becomes visible before 2:00 o'clock in the morning, and he who wants to see the sun rise, must content himself with a short night. The Exchange is one of the most elegant buildings of its class in Europe. St. George's Hall contains the largest organ in England. In front of it are the Colossal Lions and the Equestion Statue of Prince Albert. Britania (England's crest) which surmounts the dome of the Town Hall, and the Wellington Statue, both face south.

I had expected to see people dressed differently in Liverpool from what is customary in America. In this and a dozen other anticipations I was utterly disappointed. Thus I was surprised at every step, because I was not surprised.

It was a scource of great grief to me that I could not indulge in refreshments on Sunday evening. A passenger after landing, is much like a patient after the fever has left him, he is hungry all the time. I had some American silver in my pocket, which I repeatedly offered to exchange for cakes, fruits and refreshments, at the numerous stores and stands which I passed, but no one was willing to invest in my stock of change. Thus I had to suffer both from hunger and thirst, because I did not have the right kind of money. On Monday I drew my check in English currency, and bought a suitable purse; but I was very awkward for a few days at counting money. England has the oddest and most irregular money table that I found from there to Egypt, except those of Holland and Germany. Many of the coins are old and purseworn, so that it is impossible to decipher either the image or the superscription (Matt. XXII. 20), consequently the value must he guessed by their size.

I spent a great part of the day in the Museum. It contains a large and well classified collection of natural history, of objects of ancient and medieval art, of ancient manuscripts, of coins, of pictures, sculpture, &c. Saw the horns of a South African ox, each of which was about four feet long and five or six inches thick.

In the second story of the building stands a magnificent clock, weighing half a ton. Its case is about five feet long by three feet wide, and ten feet high. Upon its face are seven hands. It is a very old and complicated machine, and near it in a frame I found the following description: "It is a the work of Jacob Lovelace, of Exeter, ornamented with Oriental figures and finely executed paintings, guilted by fretworks." The movements are 1st--A moving Panorama descriptive of Day and Night, Day is beautifully represented by Apollo in his Car, drawn by four spirited coursers, accompanied by the twelve hours, and Diana in her Car, drawn by stags attended by twelve hours, represents Night. 2nd--Two Guilt Figures in Roman costume who turn their heads and salute with their swords as the Panorama revolves; and also move in the same manner while the bells are ringing. 3rd--A Perpectual Almanac showing the day of the month on a semi-circular plate, the Index returning to the first day of the month on the close of each month, without alteration even in leap years, regulated only once in 130 years. 4th--A Circle, the Index of which shows the day of the week with its appropriate planet. 5th--A Perpetual Almanac showing the days of the Month Weekly and the Equation of time. 6th--A Circle showing the leap year, the Index revolving once in four years. 7th--A Time Piece that strikes the hours and chimes the quarters, on the face of which the whole of the twenty-four hours (twelve day and twelve night) are shown and regulated; within this circle the sun is seen in his course, with the time of rising and setting by an Horison receding or advancing as the days lengthen and shorten, and under is seen the moon showing her different quarters, phases, age, &c. 8th--Two female figures, one on each side of the Dial Plate, representing Fame and Terpsichore, who move in time when the organ plays. 9th--A Movement regulating the Clock as a repeater to strike or be silent. 10th--Saturn, the God of Time, who beats in movement while the organ plays. 11th--A circle of the face shows the names of eight celebrated tunes played by the organ in the interior of the cabinet every four hours. 12th--A Belfry with six ringers, who ring a merry peal ad libitum; the interior of this part of the cabinet is ornamented with beautiful paintings, representing some of the principal ancient Buildings of the city of Exeter. 13th--Connected with the organ there is a Bird Organ, which plays when required. This unrivaled piece of mechanism was perfectly cleaned and repaired by W. Frost, of Exeter, a self-taught artist. Jacob Lovelace, the maker, ended his days in great poverty in Exeter, at the age of sixty years, having been thirty-four years in completing it. This museum also contains glass of the Roman period--A.D. 100-500. The best specimens are a little greenish, but quite clear. One of the Egyptian mummies is wrapped up by a bandage of cloth, that was woven 3,000 years ago. It is still in a good state of preservation.

Tuesday, July 6th. The Sultan of Zanzibar, who was on a tour of inspection, started from the North-western Hotel at about 10:00 o'clock to drive out to the docks. He was accompanied by two natives from his own country, and the mayor and thirteen British cavaliers. The appearance, in Liverpool, of this South African dignitary, created a considerable sensation.

At 10:45 I left Liverpool for Chester. Edge Hill Tunnel, which is about a mile or a mile and a quarter in length, was passed in five minutes. Grain ripens from one to two months later here, than in Pennsylvania. The farmers were busy making hay, and the wheat still retained a dark green color. Harvesting is done in August and September. Wheat, rye, barley and potatoes are the staple products. No corn is cultivated in northern England. Wood is so scarce and dear in Great Britain, as well as upon the continent, that the farmers can not afford to build rail-fences. Hedge-fences, walls and ditches, therefore, take their places in every European country. All this is new to the American when he first comes to the Old World. Pass some fields of clover still in bloom. See men mow with the same "German" scythes that we use in America. We reached Chester before noon. This is one of the oldest cities, if not the oldest in the country. Here one sees the England of his dreams, the England he so long desired to see, and which now presents to his gaze, as it were in a focus, both the monuments and the rubbish of many ages. It was once a great military station of the Romans in Britain, who called it the City of Legions. King Æthelfrith reduced it to ruins in the year 607, and it remained "a waste chester" (a waste castra or fortification) for three centuries. The Danes made its walls a stronghold against Alfred and Æthelred, and the Lady of the Mercians, who was the daughter of Alfred and the wife of Æthelred, recognized the importance of the place, and built it up again. It was the last city in England to hold out against William the Conqueror. During the Civil Wars the city adhered to the royal cause, and was besieged and taken by the Parliamentary forces in 1645. The Phoenix Tower bears the incription: King Charles stood on this tower September 24, 1645, and saw his army defeated on Rowton Moor.

The Rows are a very curious feature of the two principal streets running at right angles to each other. Besides the ordinary walks or pavements of these streets, there is a continuous covered gallery through the front of the second story. Some one has said, "Great is the puzzle of the stranger as to whether the roadway is down in the cellar, or he is upstairs on the landing, or the house has turned outside of the window." On this "upstairs street," as some call it, are situated all the first-class shops, the others being in the lower story on a level with the road. Picture to yourself a row of houses having porches in the second story but not in the first, and you have a correct idea of the Rows of Chester. To compare them to the Arcades of Rue de Rivoli in Paris, is a mistake, as they do not resemble those more, than a porch over a pavement resembles one in the second story.

The Cathedral is a grand old church. It was built in the latter part of the twelfth and the beginning of the thirteenth centuries, upon the same site where two of its predecessors had already crumbled into decay. "St. John's Church is even more ancient than the Cathedral, having been built in the eleventh century. I shall never forget its weather-beaten walls and its mossy roof. In many places, the thickness of the walls is greatly reduced by the rain and hail that have washed and beaten against it so long. In my rambles through Chester I had the good fortune of meeting and forming the acquaintance of an Irish Catholic Priest and a wine merchant from Wolverhampton, two intelligent and amiable gentlemen, who taught me much about those curious relics still found in heaps among the ruins of old Chester. At about 2:00 o'clock we stood upon the high square: tower of St. John's (thirty-five feet each side at the top) amidst the elderberries and grass which flourish at that giddy height. Looking at the town from this elevation, one gets no idea of its unique features, as the numerous slate-roofs give it the appearance of a modern town. The descent was made with difficulty, land even attended with some danger, for the long wooden stairs or ladders are becoming shaky and a break of one of its steps might precepitate one from such a height that instant death was the most desirable alternative. But who would not become bold, or even sometimes more that, amid such surroundings! When one says we can't get there, another is sure to declare that we must get there! "What! would you come so far to see antiquity, and then count your steps how near you would approach her?" Eight bells constitute the peal in this venerable old tower. Near by, stand the ivy-clad and moss-covered ruins of portions of the sacred edifices that date back, even to the earlier ages of the Christian era, and from among the dust and rubbish are picked up the broken images of hideous-looking idols that were the ornaments (?) of the temples once standing there. We found a large collection of those ghastly-looking idols piled away in the crypt of the church. Whether the emblems of Druid, or Christian worship, these "images cut out of stone" evidently represent an age, in which the heart was subdued by superstitious fear rather than by "love."

The Walls merit especial attention. They still surround the city completely, and form, in a certain sense, the proudest and most admirable promenade that the world affords anywhere. From it are obtained the best views of the Cathedral and of the country around. The ascent to it is made by a flight of steps on the north side of the East-gate. A ditch or canal about twenty-five feet wide, runs all around the wall and used to render the battering of the wall a matter of extreme difficulty before the invention of powder and the introduction of fire-arms. The pavement, on top of the wall, is four and a half to six feet wide, and skirted on both sides by thinner walls; that on the outside being about four or five feet high. From behind this wall the soldiers would hurl spears, javelins, &c., at the attacking enemy, and keep them in check. How things have changed since that time! Now this walk forms the peaceful and delightful promenade of the private citizens. Here meet the young and the gay, fashion displays its gaudiest colors, and lovers take their "moonlight strolls."

Such is the use now made of the Walls of Chester! America has no walled cities; Europe has but few without walls. In the early history of Europe, every town even had its walls. In many places where the walls have almost disappeared, there are still remaining the gates of the city. At those points the walls were made doubly strong, and high and impregnable towers built over them, in which were stationed strong guards "to defend the gates." Then no stranger could enter without some kind of "pass" from recognized authorities. Did not the system of "pass-ports" which has been handed down to our day, but which seems to be falling into disuse even in Europe, have its origin in this way? At 5:40 I left Chester for Birmingham. On our way we passed Crewe, one of the great railroad centers of England. At this station five hundred trains pass each other every twenty-four hours.

We arrived at Birmingham at 8:45 p.m. Between Wolverhampton and Birmingham lies the great ore and manufacturing district of England. Ore-beds and smoke-stacks cover all the area some thirty miles long and sixteen miles wide, except that occupied by the miserable cottages (some of them mere hovels) of the laborers. Looking at this immense area from the cars, it presents the appearance of one continuous town. No wonder that England can accommodate a population of some twenty odd millions on an area but little more than that of Pennsylvania, when poor humanity is thus crowded together. In the cars, I had formed the acquaintance of a sociable party of ladies and gentlemen, who pointed out places to me, and instructed me concerning the manners and social habits of the people. From Liverpool hither, I found very small brick houses the rule and spacious buildings like our Pennsylvania farm houses, the exception. Barns, I saw none; small stables supply their places even on large farms. We saw several very fine castles by the way, however.

Birmingham is known as "the toy-shop of Europe," "but most of the toys are for children of larger growth." One can nowhere see richer sights than in the show-rooms of many of these shops. One that I visited, a glass show-room containing chandeliers priced upwards of a thousand dollars, and all varieties of fancy-wares of every description, had large mirrors at the ends of the room, covering the entire walls, and producing the grandest effect conceivable. The objects in the room were thus infinitely multiplied in both directions, so that whichever way one turned his face, glittering glassware was seen "as far as the eye could reach."

Such sights are simply bewildering! It is a little difficult to gain admittance to the manufacturing departments of many of these places, but to literary characters that represent "newspapers," the doors are generally opened quite readily. In hunting these shops, I discovered a great want of system in the naming and numbering of the streets of this otherwise quite elegant city. I had passed a certain street twice, from end to end, in search of a particular number. Upon further inquiry, I learned that what I had considered one street, was numbered and named as two, though there was not the slightest deviation from a perfectly straight line at any point of it. To make bad worse, the houses were counted and numbered upwards on one side of the street, and downwards on the other side. In such a city the stranger must find places by speculation!

Strange things one meets at every step in Europe, and soon gets so used to it, that it seems the strangest to see something that is not strange; but oddities are perhaps no plentier on one side of the Atlantic than they are on the other, and are equally amusing everywhere. Upon the burial ground of St. Philip's, stands a monument in honor and memory of a wife that died at the age of fifty-nine years, which has a bee-hive and the inscription: "She looked well to the ways of her household, and did not eat the bread of idleness."

A number of fine statues adorn some of the public squares. One of these, a bronze statue to Peel faces east; while Priestley's marble statue faces south.

The first thing that arrests the tourist's attention on arriving at Birmingham, is its magnificent railroad station, the largest and finest that I had thus far met with in England. As it was late in the evening when I arrived, I had no time to pay much attention to it until the next day. The part entered by the trains is about 1,050 feet long and 200 feet wide, all in one apartment. This part is sprung by forty-two immense iron arches, supporting a roof half of whose covering is glass. The numerous tracks are separated by platforms running lengthwise through the building, from which the passengers enter the cars. In order to avoid the danger of crossing the tracks, there is a fine foot-bridge, eighteen feet wide, running across the tracks above the reach of the locomotive stacks. From this bridge, stairs descent to the platforms between the tracks, as before mentioned. Three hundred trains pass through this station every twenty-four hours. An officer receives and dismisses these trains by means of a signal-bell. The ticket-offices are in the second story of a large building adjoining.

There are no "conductors" upon the trains after they leave the "stations" (which, by the way, I never heard any one call depots, in Europe) but officers are stationed at the head of every stairway to punch the tickets. Five minutes before any particular train leaves, the ticket-office is closed and the conductors pass through the cars and inspect the tickets. If any one did come into a wrong car or train, there is still time left to correct the mistake. Tickets are not collected till one's destination is reached, where they must be delivered to the door-keeper on leaving the station. Without it, a passenger is a prisoner. "Railroading" is so perfectly systemized in Europe, that it is quite impossible either to cheat a company, or to be cheated out of one's time by missing trains. There is little danger of missing a train even in countries where one can not speak the language. The cars are divided into compartments (Ger. Abtheilungen) of two seats or benches each, running across the car, with doors at the sides. In 1st Class cars, the seats are finely cushioned and the compartments are about as inviting in appearance as our Palace cars; in 2nd Class cars the seats are comfortable but common; but 3rd Class cars have only bare wooden benches. There are in some countries, 4th Class cars, which have no seats. I did not see any of those, but from what I learned of others, they must resemble our freight cars. In those, too, passengers have the privilege of standing or sitting down, according to their taste or comfort. Tickets to 1st Class cars cost about the same as in this country, 2nd Class tickets cost three-fourths, and 3rd Class about half as much.

In hilly sections of the country, the railways generally cross the wagon roads by bridges; but wherever the two kinds of roads intersect each other on a level, travel on the latter is interrupted by gates and watchmen, who permit no one to pass while a train is approaching the crossing. Thus every railway crossing in Europe is superintended day and night by watchmen. These watchmen are noticed by signal-bells, at the departure of every train running in the direction of their crossings. Under such a system, accidents are impossible. Even the doors of each "compartment" are barred by the conductors before the trains are dismissed, and will not be opened by the conductors of the next station, until the train stands still. The tickets, besides containing the ordinary matter on tickets in this country, have also the price printed upon them.

Some of the stations of the Old World, are buildings of extraordinary beauty and magnificence.

The grandest structure of this kind, is, probably, the station (Ger. Station or Bahnhof, Italian Stazione) of Stuttgart. Among many others, might also be mentioned the stations of Paris, of Turin, of Milan, and of Rome; but the Great Western Station of London, lakes the palm of those all, for magnificence, beauty and convenience combined. What the station at Clapham (seven miles above London) looks like, I do not know, but it is said, that from 1,000 to 1,200 trains run through it every twenty-four hours! What multitudes of people must be streaming over the platforms and past the windows of the ticket-offices of such a station, every day! At Birmingham and at Crewe, where 300 and 500 trains pass daily, the swarming thousands remind one of floods and inundations, but how must it look at Clapham?

July 7th, 3:40 p.m. Leave Birmingham for Stratford on the Avon (pron. ā'von).

Arrived at 5:00 p.m., July 7th. It had been my intention to pay this place only a brief visit, giving but a glance at "The Poet's" home and birthplace, and then start on foot for Coventry; but I soon found that Stratford possesses more charms than I had anticipated. Shakespeare's fame has an influence over his native town, that is simply marvelous.

The thousands of tourists that come from every land, and from every clime, to see the scenes that the poet saw, and breath the same air that he breathed, make the place one of the most popular resorts of literary pilgrims, that can be found anywhere.

The buildings of Stratford are small and low, as is the rule, rather than the exception, in English towns and villages. Many are covered with tiles, but the thatch roof is also very common here. This consists of a mixture of straw and earth, often more than a foot in thickness, and covered with moss and grass. Notwithstanding this, both the houses and the streets are kept remarkably clean and inviting; so much so, that I felt nowhere else so soon and so perfectly at home as here. Its people seem to be possessed of every virtue, and preëminent among them all, is that of hospitality which seems to be blooming in the hearts of all its citizens to-day, as did poetry in the mind of Shakespeare three hundred years ago.

The streets of this town are kept as clean as a floor, by sweepers watching the streets all day long, collecting and carrying away all the refuse matter. One day, I felt ill at ease about a small piece of paper that had become a superfluity in my pocket, but which I was afraid to throw upon the street, as it would there seem as much out of place as if I should drop it upon the carpet in a parlor. I passed along the pavement with it, until I met a street-sweeper, and there threw it upon his heap with a nod, which he reciprocated with a bow.

On entering Stratford, my foot first tended toward

a large two-story house, about fifty feet long, having three large dormer-windows and two chimneys, one of them running up on the outside of the house.

The custodian takes the visitor through every apartment of it, giving the history of the same and of numerous articles of furniture and Shakesperian relics, &c., which constitute a considerable museum.

When William Shakespeare's father was a "well-to-do" man, he occupied the whole house; but after he had become poor, the east end was rented to a hotel-keeper, and he lived in the middle part only, which has later been used as a butcher-shop.

"On the 16th of September, 1847, it (the building) was put up for sale by the magniloquent Mr. George Robins, and in consequence of a strong appeal to the feelings of the people, made through the public press, by which a National Subscription was raised for the purpose; this house was bought at the bidding of Mr. Peter Cunningham, for something more than 3,000 pounds sterling, and was placed under Trustees on behalf of the Nation."

Space will not permit me to make mention of more than a few of the many interesting books, manuscripts, works of art, antiques and relics, found in this Library and Museum. Among them stands the desk at which little "Willie" sat at school, also a ring which he wore at his thumb (later in life), and upon which are engraved the letters "W.S." and a "true lover's knot." I spent nearly an hour here, a studying how things looked in Shakespeare's time. The ground floors of the house, are covered with flagstones broken in varied forms, as accident would have it, while the rough massive timbers of the floors above stand out unpainted and unplastered. After taking a pleasant walk, with a gay party, through the garden, in which are cultivated all the flowers of which Shakespeare speaks in his works, and, (I must not fail also to mention), after having taken our turns in sitting upon Shakespeare's chair, I bade the sociable company "good-by!" and started for

"a genuine country village, consisting of a few straggling farm-houses and brick and timber cottages, standing apart from each other in their old gardens and orchard-crofts. Simple, old-fashioned, and almost untouched by the innovations of modern life, we are here amidst the charmed past of Shakespeare's time." Here is still to be seen, the cottage in which was born and lived Anne Hathaway, the wife of Wm. Shakespeare. This village lies about a mile from Stratford, and is approached by a pleasant walk across quiet and fertile fields and pasture lands, the same path along which "Willie" used to steal when he went a-wooing his Anne. The Hathaway cottage is a large old-fashioned thatch-roofed building--very plain but very homely. The clumsy string-lifted wooden door-latches, and the wooden pins fixing the framing, and which have never been cut off, but stick up some inches from the wall, are still all there. It was dusk before I got there. My rap at the door was responded to by the appearance of an old lady custodian, a descendent of the Hathaway family, who immediately busied herself to light a tallow candle. That being successfully accomplished, she commenced her story by pointing out the old hearth, and explaining the kitchen arrangements of olden times. Among the old articles of furniture, is a plain wooden settee or bench which used to stand outside against the house near the door, during the summer, and which, as tradition, has it, was Willie's and Anne's courting settee. Pictures of their courtships hang against the walls, exhibiting styles and fashions well in keeping with the antique furniture of the room. An old carved bed-stead of the Shakespeare era, stands in the room above. Here the custodian offered me a book of autographs, asking me to sign my name, as has been customary since October 4th, 1846. Six books have been filled with autographs, since that time. Among the signatures I saw one Emma R., July 24th, 1866. "This," said the custodian, "is the signature of the Queen of the Sandwich Islands."

Henry W. Longfellow's signature, who was here with his brother (and families), June 23rd, 1868, and that of Chas. Dickens, here in 1852, were also pointed out.

The old lady would not let me go away without having taken a drink from "the spring where Anne used to drink." After presenting me with "lavender" and "rosemary" for mementoes, and a button-hole boquet consisting of a fine rose and buds, for immediate display, she wished me god-speed on my journey, and I retraced the path across the fields to Stratford.

New Place, the Home of Shakespeare, is the most charming place in all Stratford. The extensive yard and garden which belonged to the property in Shakespeare's time, had been partially cut up in lots and covered with houses; but these have all been removed again, and the grounds laid out into walks, lawns and flower beds, as the poet was wont to have them. His yard and garden covered an area of about two acres. The gentleman who has charge of the property now, exerts himself to the utmost, to make the surroundings pleasant and inviting, aiming particularly to plant the same trees and flowers that the poet had planted there, and to keep his favorite trees, or lineal successors of them, in the same sites. Among the ornamental trees and flowers, he pointed out a number that he obtained from Vick, the florist, of Rochester, N.Y.

Shakespeare was buried in the Church of the Holy Trinity. His wife, his only daughter Susanna and her husband, Thomas Nash, lie with him in the same row, immediately in front of the altar-rails. His tombstone bears the following inscription:

GOOD FREND FOR JESVS SAKE FORBEARE,

TO DIGG THE BVST ENCLOASED HEARE:

BLESE BE YE MAN YT SPARES THES STONES,

AND CVRST BE HE YT MOVES MY BONES.

The only typographical peculiarity not rendered here, is the grouping together of HE in HEARE and TH in THES, after the fashion of monograms.

This church also contains a half-length figure of Shakespeare, painted after nature. There is evidence extant that it had already taken its place against the wall in the year 1623. Beneath is inscribed:

Judicio pylivm genio socratem, arte maronem,

Terra tegit, popvlvs mæret, Olympvs Habet*

Stay, passenger; why goest thov by so fast?

Read, if thov canst, whom enviovs death hath plast

Within this monvment; Shakespeare, with whom

Quick natvre dide; whose name doth deck ys. tombe

Far more than cost; sith all yt. he hath writt

Leaves living art bvt page to serve his witt.Obiit. Ano. Doi. 1616.

Ætatis 53. Die 23. Ap.

[In judgment a Nestor, in genius a Socrates, in art a Virgil. The earth covers him, the people mourn for him, Olympus has him.]

Of the Guildhall, the Grammar School, and the beautiful Avon, with their hundred sweet associations, I dare say nothing more. After a stay of three days, during which time I had recovered from the effects of the severe strain and close application of mind and body, by which both had suffered exhaustion, and been driven almost to the verge of prostration, in the museum at Liverpool and the ruins of Chester; I started on way to Warwick (pron. War'rick) and Coventry. As my purpose was to walk the whole distance, about twenty miles, I sent my sachel by rail, to the former place.

This is the walk referred to by the two Englishmen who laid a wager as to which was the finest walk in England. "After the money had been put up, one named the walk from Stratford to Coventry, and the other from Coventry to Stratford. How the umpire decided the case, is not recorded." It was late in the afternoon on Saturday, July 10th, when I bade adieu to Stratford, and went away rejoicing, in the hope of soon seeing the beauties of England's most charming agricultural section.

After two hours, I entered Charlecote Park, where I disturbed several herds of deer, some hundred head in all. From this park, as lame tradition has it, Shakespeare once stole deer, and became an exile for the crime!

On Sunday forenoon I attended service at

in Warwick. The choir, lady chapel and chapter-house are among the purest examples of Decorated work, and date from 1394. The tomb of Richard Beauchamp (Bee'cham) in the Lady Chapel, is considered the most splendid in the kingdom, with the single exception of that of Henry VII. in Westminster Abbey.

A very high tower stands over the entrance door, at the west end of the church. The organ and choir (at the same end) rendered the finest music that I heard in England. There were several very highly cultivated voices among those of the half dozen ladies that occupied the space in front of the organ. Everything else about the services is eminently examplery of the olden times. Preaching is the least important part of the exercises. Pulpit oratory finds no place here. Singing, praying and readings are the leading feature of worship in the English Church in general, and of old churches like this, in particular. Such exercises seem to be eminently appropriate for a people whose hearts and minds are almost petrified in civil and religious forms and ceremonies. The step which the English Church took away from Catholicism, must have been an extremely short one, if it was a step at all. This congregation still turn their faces toward the east, during a certain part of their recitals, and bow ceremoniously, in concert, as often, as they mention the name of "Jesus Christ."

Two miles from Warwich, is Leamington, (Lĕm'ington), a fashionable "spa," which I visited in the afternoon. It is a very pretty town, and emphatically modern in style; presenting nothing that is anti-American in appearance, except its clusters of chimney-tops, so common everywhere in Europe. As soon as one has crossed the Atlantic he will seldom longer see single square tops built upon the chimneys, but each apartment of the house has its own chimney; all these converge, but do not meet before coming out of the roof, so that from two to six or eight tops generally keep each other company on the house-tops.

At 3:45 p.m., I started from Warwick for Coventry. The road leading from this place to Coventry is an excellent turnpike, just as that is from Stratford hither, and has a splendid gravel walk for pedestrians on one side, and a riding path for those on horseback, on the other side.

Five miles brought me to Kenilworth Castle. Great must have been its glories when Elizabeth came here in 1575 to visit Liecester. Cromwell dismantled it, and laid waste the gardens around it, and the tooth of time has been gnawing at it ever since, but it is magnificent even in its ruins. "Go round about it, tell the towers thereof, and mark well its bulwarks, if you would know what a mighty fortress it must have been when it held out for half a year against Henry III. in 1266, or what a lordly palace when it thrice welcomed Elizabeth to its hospitalities, three hundred years later."

A quarter or half a mile further on, is a fine church, and nearby an ivy-covered arch. A passing gentleman told me this had been the entrance to an ancient abbey; and others said it was a part of the ruined Castle of Kenilworth.

It was 6:00 o'clock when I left here, and had five miles more to Coventry. A mile and a half on this side of that city lie the extensive possessions of Lord Leigh. This wealthy peer owns here, in one stretch, about twenty square miles of the finest and most fertile land in the world.

About a mile from Coventry I encountered an enormous stream of pedestrians coming out of the city to take their evening walk. The promenade, which is about ten feet wide at that place, was so thronged with the gay young couples, that I found it impossible to walk against the mighty stream, and took the middle of the street. After. I had entered the gate, I found the pavements on both sides of the road becoming more and more crowded, all bound for a pleasant grassy grove known as "the lovers quarters."

It is difficult to make estimates under such circumstances, but there can hardly have been less than 5,000 to 10,000 persons upon the promenade that evening.

Coventry is remarkable for its elegant parish churches, which are among the finest in England.

"St. Michael's Church is one of the largest (some say the largest) and noblest parish churches in England." Its steeple built between 1373 and 1395, is 303 feet high. The church was finished in 1450, when Henry VI. heard mass there. The second and third of the "three tall spires" of Coventry are that of Trinity Church and of Christ Church. St. John's is famous for its magnificent western window.

Coventry is well worth, a visit on account of those famous churches.

I was accompanied to those fine edifices by two precociously intelligent little beauties, (of seven and eleven years respectively), whose gayety and cheer fulness not only rendered their society very accept able to "a stranger in a strange land;" but the simple fact of their being permitted to accompany so perfect a stranger to all parts of the city, showed how much trust some foreigners have in Amercans, and consequently, to what extent one may put confidence in them. Such incidents are very pleasant and encouraging to the lonely pilgrim and may be made a matter of almost daily occurence by any social but circumspective traveler. The traveling public in Europe are so social, and etiquette so free, that the tourist can at every step form the acquaintance of some one who is bound for the same church, museum or pleasure garden and thus be continually enjoying the benefits of intelligent and cheerful company.

On Monday noon, July 12th, I left Coventry by rail, to return to

At 3:30 p.m., I had passed through the many elegant apartments of Warwick Castle, and stood at the top of its tower, overlooking the wood groves, and flower garden, occupying the 70 acres of ground belonging to that princely mansion.

Among the ornamental trees, our guide pointed out "one that Queen Victoria planted with her own hands." Scott calls Warwich Castle "the farest monument of ancient and chivalrous splender which yet remains uninjured by time."

It is said to have been founded in the 10th century, destroyed in the 13th, and restored by Thomas de Beauchamp in the 14th. It has been preserved so well that it looks almost like a new palace, to-day

with its score of colleges scattered all over the city, constituting the world renowned University of the same name, was "done" the next day, but done in a hurry. It is a depressing business to pass by so much, giving but a glance here and there, and not be able to see so many things more at leisure, Magnificent libraries and museums, grand churches and chapels, and extensive buildings and botanical gardens, were rushed through and passed by, as if the charm and beauty of Oxford's scenes consisted rather in making the images of them flit in quick succession across the retina of the eye, than in examining, studying and contemplating them.

Merton College, founded 1264, contains a library 600 years old. Many of its large and rare books are chained to their respective shelves, like dogs to their kennels; and with chains too, of sufficient strength to check any canine's wanderings. Christ Church I entered by the Tower-Gate, so named after the great bell contained in the cupola of the tower over it. This bell weighs about 17,000 pounds. The quadrangle inclosed by the buildings of this college, is "the largest and the most noble in Oxford." Its dimensions are 264 by 200 feet, or nearly an acre and a half in extent. The "Hall" is 113 feet by forty, and fifty feet in height. "The roof is of carved oak, with very elegant pendants, profusely decorated with the armorial bearings and badges of King Henry VIII. and Cardinal Wolsey, and has the date 1529." Its bay window at the end of the dais with its rich grained vault of fan-tracery, is admired by every one.

Christ Church Meadow, with its "Broad Walk" one and a quarter mile in circuit, and Addison walk, near St. Mary Magdalen College, are among the most bewitching promenades that can be found anywhere, while "the manner in which High street opens upon the view, in walking from the Botanic Garden, is probably one of the finest things of the kind in Europe."

Oxford is all history and poetry. There is a tradition that upon the top of the elegant tower St. Mary Magdalen, formerly on every May-day morning, at four o'clock, was sung a requiem for the soul of Henry VII., the reigning monarch at the time of its erection. The custom of chanting a hymn beginning with

"Te Deum Patrem colimus,

Te laudibus prosequimur,"

In the same place is still preserved, on the same morning of each year, at five o'clock.

The dark lantern which Guy Fawks used in the Gunpowder Plot in 1605, and a picture of the conspirators are contained in the New Museum.

From Oxford I went directly to London by a fast line, which occupied less than two hours in making the journey. From the cars, we saw Windsor Castle, with its colors raised, meaning that the Queen was there.

We also passed some large patches of flowers in the fields, which were cultivated for the London flower-market.

Foreigners in general have a great passion for flowers. While ladies wear them in their hair, upon their bosoms, and carry them in their hand, the gentlemen will carry button-hole bouquets, and many even stick them upon their hats. They are fashionable with all ages and all classes. From blooming maidenhood to gray-headed age, all will adorn themselves with flowers. The English seem to cultivate the most flowers, while the French and the Italians, and (lately?) the Germans, wear most upon their persons. In England, every available spot of spare soil about the yard, is planted with flowers; on the continent, all the fashionable restaurants and cafes must daily be supplied with fresh bouquets, with which these halls are decorated in lavish profusion.

We now approach London, the mighty mistress of the commercial world, the most populous city on our globe. Here, certers the trade of all nations here, is transacted the business of the world. If you would know how it looks where concentration of business has reached its climax, then come to London. Many of its streets are so crowded with omnibuses, wagons, dray-carts, &c., that it is almost Impossible for a pedestrian to cross them. When the principal streets intersect each other, the bustle and tumult of trade is so great, that it becomes a dangerous undertaking to attempt to effect a crossing at such a square.

For the protection and accommodation of those on foot, the squares are provided with little platforms elevated a step above the surface of the road and surrounded with a thick row of stone posts between these, the pedestrian can enter, but they shield him from the clanger of being tread under the feet of horses, or run over by vehicles. Here one stands perfectly safe, even when everything is confusion for an acre around. As soon as an opportunity opens, he runs to the next landing; and thus continues, from landing to landing, until the opposite side of the square is reached. It often requires five minutes to accomplish this feat. It has been estimated that no less than 20,000 teams and equestrians, and 107,000 pedestrians cross London Bridge every twenty-four hours. By police arrangement, slow traffic travel at the sides and the quick in the center. It is 928 feet long and fifty-four wide. Not only are the streets crowded, but beneath the houses and streets, in the dark bosom of the earth, there is a net-work of

extending to all parts of the city, which pick up that surplus of travel which it has become impossible to accomplish above.

There are some thirty miles of tunneled railways in London, now, and the work of extending them is carried on with increasing energy. This railway is double track everywhere, and forms two circuits, upon one of which the trains continually run in one direction, while those on the other track run in the opposite direction. Collisions are therefore impossible between these two systems of counter-currents. Numerous stations are built all along these roads, where travelers can descend to meet the trains or leave them, to make their ascend to the city above. To give the reader an idea of the immense amount of traveling done in these dark passages under London, it need only be stated that long trains of cars pass each station every "ten minutes," and are as well filled with passengers as those of railroads on the surface of the earth. The cars are comfortably lighted, so that after one has taken his seat and the train begins to run along, it resembles night-traveling so perfectly, that the difference is scarcely perceptible.

Of all modes of travel, these underground railroads afford the quickest, cheapest, safest and most convenient manner of transit.

This great metropolis includes the cities of London and Westminster, the borough of Southwark, and thirty-six adjacent parishes, precincts, townships, &c. It covers an area of 122 square miles, and has a population of about 4,000,000, that of the City of London proper being no more than about 75,000. Murray's Modern London contains the following statistics:

"The Metropolis is supposed to consume in one year 1,600,000 quarters of wheat, 300,000 bullocks, 1,700,000 sheep, 28,000 calves, and 35,000 pigs." (If these animals were arranged in a double line, they would constitute a drove over a thousand miles long!)